Abstract

In contrast to the majority of allergic or hypersensitivity conditions, worldwide anaphylaxis epidemiological data remain sparse with low accuracy, which hampers comparable morbidity statistics. Data can differ widely depending on a number of variables. In the current document we reviewed the forms on which anaphylaxis has been defined and classified; and how it can affect epidemiological data. With regards to the methods used to capture morbidity statistics, we observed the impact of the anaphylaxis coding utilizing the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases. As an outcome and depending on the anaphylaxis definition, we extracted the cumulative incidence, which may not reflect the real number of new cases. The new ICD-11 anaphylaxis subsection developments and critical view of morbidity statistics data are discussed in order to reach new perspectives on anaphylaxis epidemiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Anaphylaxis epidemiology: open introductory questions

Anaphylaxis has been defined for clinical use by healthcare professionals as a serious, generalized, allergic or hypersensitivity reaction that can be life-threatening and even fatal [1,2,3]. In contrast to the majority of allergic or hypersensitivity conditions such as asthma or rhinitis, accurate worldwide anaphylaxis epidemiological data remain lacking for harmonization. Data can differ widely depending on a number of variables. For instance, European data have indicated incidence rates for all-cause anaphylaxis ranging from 1.5 to 7.9 per 100,000 person/year, with an estimate that 0.3% (95% CI 0.1–0.5) of the population will experience anaphylaxis at some point during their lifetime [4]. As well, it is estimated that 1 in every 3000 inpatients in US hospitals suffer from an anaphylactic reaction [5].

Although available data, specifically those collected during the past decade, show an increased frequency of anaphylaxis, there are still challenges in interpreting these informations [6, 7] and its global applicability. The most widely discussed issues in the epidemiology of anaphylaxis filed over the last 10 years are: (I) regional variations in concepts and definitions (Fig. 1) [1,2,3, 8,9,10], (II) whether prevalence or incidence is the best measure of the frequency of anaphylaxis in the general population, (III) whether the frequency of anaphylaxis is higher than previously thought, and (IV) whether the increasing incidence published is real or reflects different methodologies and definitions used.

Over the last several years, an increasing number of clinical databases have been developed to capture reliable anaphylaxis epidemiological data at both national and regional levels (Fig. 2). However, a substantial proportion of the current data on the epidemiology of anaphylaxis has come from registries with limited scope and population source. Different methods have been applied in an attempt to reach reliable epidemiological data, but most of the studies have focused on specific triggers or at-risk populations. Lack of harmonized strategies to record anaphylaxis cases hampers collection of comparable epidemiological data. In general, registries are representative sources to reach epidemiological data, and are applied only if the reporting of the conditions is mandatory and the data are validated.

On the other hand, broad population-based studies allow descriptive and analytic epidemiological analysis covering the general population and identify all or a known fraction of the cases in a particular community. Generally speaking, population-based studies have adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) as the main tool to capture the proposed outcomes. These studies have been especially useful in detailing time-related trends, capturing clinical practice and principal discharge diagnosis coding statistics, and in providing broader morbidity and mortality statistics (MMS). However, anaphylaxis has never been well classified under the ICD context, either for morbidity [11] (Table 1) or for mortality data [12]. This is exemplified by the under-notification of anaphylaxis deaths using the Brazilian national mortality database [12]. An important reason for this is the difficulty of coding anaphylaxis fatalities under the WHO ICD system. In most countries, mortality statistics are routinely compiled according to regulations and recommendations adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA). Causes of deaths are classified and grouped according to the ICD edition in use at the time and the information on death certificates is collected using the international form recommended by the WHO. However, a limited number of ICD-10 codes are considered to be valid for representing underlying causes of death on the current death certificates, and with regard to anaphylaxis as such, there are simply no valid codes [12].

Taking the opportunity presented by the ongoing ICD-11 revision, the under-notification of death data [12] triggered a cascade of strategic international actions supported by the Joint Allergy Academies and the ICD WHO governance [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] to update the classifications of allergic conditions for the new ICD edition. These efforts have resulted in the construction of the new “Allergic and hypersensitivity conditions” section built under the “Disorders of the Immune system” chapter [17, 24].

In order to better delineate the proposed changes and follow the ICD-11 revision agenda, we reviewed the forms on which anaphylaxis has been defined and classified, and the published anaphylaxis epidemiological data, particularly with regards to the methods used to capture morbidity statistics.

Anaphylaxis: reaching answers based on definition and classification

Anaphylaxis definition impacts in epidemiological data

All anaphylaxis guidelines [1,2,3, 8,9,10] have consistently defined anaphylaxis as a severe life-threatening generalized or systemic hypersensitivity reaction. Being described as a reaction implies a risk of overestimating the prevalence of anaphylaxis. For some conditions, such as asthma, the number of patients with the condition is different from the number of (asthma) exacerbations (Fig. 3a). However, using the definition of anaphylaxis, the number of exacerbations (reactions) can be wrongly taken as the number of cases (disease) (Fig. 3b), resulting in an overestimated lifetime cumulative incidence.

Incidence is the measure of the frequency of a new case (or condition) in a population at risk within a period of time. Therefore, given that anaphylaxis is an acute condition with long asymptomatic periods during which the risk of relapse can decrease over time in some patients or when culprit factors such as allergens are avoided or counteracted (e.g. stinging insect venom immunotherapy), knowing the number of new episodes (incidence) over a specific period can not be an adequate measure of frequency. Cumulative incidence, also known as incidence proportion may be not an adequate measure for frequency of anaphylaxis, since the reaction is no longer active once the episode is resolved. For this reason, more detailed data on recurrent episodes are required to overcome this challenge in anaphylaxis epidemiology studies.

Updated anaphylaxis classification and coding in the ICD

The ICD is the broadest classification and coding system used to monitor the incidence and prevalence of diseases and other health problems, reflecting the general health situation in countries and populations [25].

Taking the example of the ICD-10 (2016 version) [26], anaphylaxis has been classified under the “XIX Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes” chapter, specifically the “T78 Adverse effects, not elsewhere classified” section. Under this section, different hypersensitivity conditions are classified at the same level, such as “Anaphylactic shock due to adverse food reaction”, “Angioneurotic oedema” and “Allergy, unspecified” (Table 1), reflecting a misunderstanding of concepts used by the health care professionals on a daily basis.

The construction of the new ICD-11 section addressing to allergic and hypersensitivity conditions now allows anaphylaxis to be properly classified and attaining greater visibility within ICD (Table 1). Currently, this subsection contains 7 main anaphylaxis headings to be combined with severity and causality classification/specifications. The building process of this framework resulted from combined efforts and constant discussions with the groups of experts and the ICD WHO governance.

The construction of the new subsection addressed to anaphylaxis means that it will now be recognized as a clinical condition requiring specific documentation and management.

Lessons from population-based anaphylaxis morbidity epidemiology publications

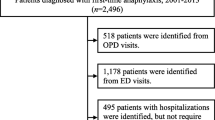

From 19th to 26th October 2016, 1896 manuscripts were selected using PubMed Mesh terms “anaphylaxis epidemiology”, “epidemiology of anaphylaxis” or “anaphylaxis epidemiology population-based studies”. After removing those published before 2011 and those not published in English, there were 532 papers published in the last 5 years. We did not include case reports, studies in animal models, quality of life studies, fatality studies, guidelines or reviews (Fig. 4). All publications were independently evaluated by two co-authors and disagreements related to the inclusion into the analysis were resolved through open discussion and consensus.

We analyzed methodological aspects, main outcomes and databases used in the remaining 15 publications selected as eligible according to the selection criteria (Fig. 4) from different countries. The methods used and the definitions taken varied among the publications; however, 67% focused on rates of hospitalization or emergency department admissions. National databases were used in 67% of the studies. Overall, 40% were large population-based studies and 100% of these documents used the ICD definition as the starting point of the analysis (Table 2). Based on ICD registries, regardless of the ICD version used, 71% of all the studies had to utilize secondary data in order to capture the anaphylaxis data, meaning that the data have been affected by the misclassification of anaphylaxis in the previous versions of the ICD.

Most of the studies (60%) did not address the possibility of recurrence of episodes, and, therefore, of cumulative incidence. This highlights the need to distinguish the number of patients with anaphylaxis per year from the number of episodes per year. Even with the alternative strategy of reaching the mean number of anaphylaxis cases within a started time, data would be influenced by the methodology and definitions applied. In other words, most of epidemiological studies considering incidence as the main variable may be overestimating the number of anaphylactic patients. True frequency of anaphylaxis is also possibly underestimated due to under-recognition by patients and caregivers and under-diagnosis by health care professionals (e.g.: difficulty on diagnosing anaphylaxis in the absence of hypotension or shock).

Reaching new perspectives for anaphylaxis epidemiology

In this manuscript, we provide arguments for the need of reviewing the current definitions in use for anaphylaxis. The definitions are able to directly impact in the epidemiology of anaphylaxis as a disease. Incorporating refined strategies to achieve accuracy and comparable MMS can support public health changes to reach better patients’ care and prevention worldwide.

Due to recent achievements at the international level on enhancing terminology, classification, definitions and coding of allergic and hypersensitivity conditions through the ongoing WHO ICD revision process, anaphylaxis is now considered a condition. Importantly the new classification system for anaphylaxis will surely enable the collection of more accurate epidemiological data to support quality management of patients with allergies, better health care planning and decision-making and public health measures to reduce the morbidity and mortality attributable to anaphylaxis.

Based on current developments, reviewing the definition of anaphylaxis and epidemiology strategies by clarifying differences between anaphylaxis episodes (reactions) from anaphylaxis as a condition itself will lead to more precision on MMS. Cumulative incidence is an inadequate measure here, since the reaction is no longer active once the episode is resolved and one patient can present different episodes of anaphylactic reactions in his/her life. Most of the publications have so far considered the episodes (illness), regardless to the subject suffering of this condition (patient). A possible strategy in order to avoid cumulative incidence of anaphylaxis would be reaching recurrence of anaphylactic episodes. Consistent scientific, economical and political changes may follow this move, which will likely be reflected in better management of patients with anaphylaxis worldwide. For instance, precise and broader anaphylaxis MMS will support the global availability of auto-injectable adrenaline, currently available in less than 35% of all countries [23]. Specific focus in the patients’ care, and not just in the episodes, would also support primary and secondary prevention actions.

As demonstrated, anaphylaxis regional epidemiological data differ considerably according to many variables and it is still unclear whether the increasing incidence published is real or the results reflect different methods used to define and characterize anaphylaxis. However, based on current statistics [4, 5], severe anaphylaxis fits well the definition of a rare disease. Conceptually, rare diseases can be defined as life-threatening or chronic debilitating disorders, which are of low prevalence and typically require a multi-disciplinary approach to address prevention and treatment. The Orphanet, lead by the French National Institution of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and the French Ministry of Health, is responsible for developing an inventory of rare diseases and a classification system which could serve as a template to update International terminologies. When the WHO launched the revision process of the ICD, a rare diseases Topic Advisory Group was established. So far 5400 rare diseases listed in the Orphanet database have an endorsed representation in the foundation layer of ICD-11 [27, 28], but severe anaphylaxis is not yet included on the list. In addition to all the benefits expected by the actions to update terminology, definitions and classification of allergic and hypersensitivity conditions through the ICD-11 revision, we strongly believe that anaphylaxis is a public health priority, therefore in order to strengthen awareness and quality clinical management of patients it should therefore be formally added to the list of rare diseases. Including severe anaphylaxis into the list of rare diseases may allow, in first instance, the allocation of resources to better understand the national and global epidemiology of anaphylaxis as a disease; monitor the patterns of this disorder to follow hospitalizations, mortality, avoidable deaths and costs. Having more precise epidemiological data may support the global availability of adrenaline auto-injectors worldwide at affordable price addressed to the patients’ care through argumentation with national bodies and stakeholders. For instance, the French Ministry of Health, in coordination with the State Secretariat for Higher Education and Research, implements a proactive policy based on the mobilization of health/research professionals and patients’ associations in order to improve quality diagnosis, management and prevention of the 3 million patients affected by rare diseases in France. This health intervention/policy model can be took as an example in different countries in order to implement essential actions according to individual national needs, such as the availability of adrenaline auto-injectors in low incoming countries [23].

Anaphylaxis epidemiological publications are also hampered by the inclusion of all severity degrees of anaphylaxis. Mild reactions in which manifestations are generally limited to one organ or system, such as the skin, usually do not incur any risk of death. The inclusion of these cases in the epidemiological studies provides mistaken perception of high and increasing incidence of severe anaphylaxis. Our focus would be addressing severe reactions in which the risk of mortality is strong and requires additional prevention measures and a coordinated management such as the one provided by the rare disease network in our country. To date, there is no available data regarding severe cases of anaphylaxis in Europe. French data suggests that less than 30,000 people are affected by severe anaphylaxis and, 9.2 per 100,000 person-years based on the University Hospital of Montpellier data [29]. Australian data demonstrated the increasing number of patients at risk of anaphylaxis, from 0.98% in 2009 reaching 1.38% in 2014 in school aged children. In contrast, the number of adrenaline auto-injectors activated (severe cases) per year per 1000 students at risk of anaphylaxis was 6 and 8 in 2010 and 2014 respectively [30]. If taken as isolated data of patients at risk, it can drive readers to think that anaphylaxis is increasing in this country. However, the administration of the treatment as objective data indicates that severe anaphylaxis can be considered as rare disease.

The ICD-11 intends will be presented to the WHA in 2018. A known issue regarding accurate epidemiological data and miscoding is the lack of training regarding how disorders should be classified and coded in administrative and institutional databases. For this reason, the core ALLERGY in ICD-11 operational team (LKT, PD) in collaboration with the WHO and with the support of our international academies network, intends to implement education tools to support the allergy community in the transition process, preparing health professionals and stakeholders for the new logic of the ICD-11, when it is launched. Educational efforts will also help to decrease the under-recognition of anaphylaxis by patients, caregivers, and health professionals, health authorities and governments and have been the main aim of allergy academies by promoting education programs and publications in the field.

The construction of the new section dealing with anaphylaxis means that the latter will now be recognized as a clinical condition requiring specific documentation and management. Besides increasing the accuracy and sensitivity of clinical diagnosis data, unifying the allergic and hypersensitivity conditions into a single section of the ICD, endorsed by the WHO ICD governance bodies can be considered a strong epidemiological, economical and political move that advocates to optimal diagnosis and management of allergic patients worldwide. By allowing all the relevant diagnostic terms for anaphylaxis to be included into the ICD-11 framework, WHO has recognized their importance not only to clinicians but also to epidemiologists, statisticians, health care planners and other stakeholders. In the current manuscript we raise awareness of the outcomes of the ongoing ICD revision process as an instrument that has been developed to provide more precise anaphylaxis MMS to ensure comparability in monitoring, decision-making and achieving quality clinical practice. Meanwhile we propose strategies to improve anaphylactic patients’ care through reviewing definitions and epidemiological data. This document and critical view intend to support national and international health interventions and health policy changes.

Abbreviations

- AAAAI:

-

American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology

- ACAAI:

-

American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology

- ASCIA:

-

Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy

- EAACI:

-

European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- MMS:

-

morbidity and mortality statistics

- NIAID/FAAN:

-

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network

- WAO:

-

World Allergy Organization

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF Jr, Bock SA, Branum A, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network Symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:391–7.

Simons FER, Ardusso LR, Bilò MB, Cardona V, Ebisawa M, El-Gamal YM, et al. International consensus on (ICON) anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;30(7):9.

Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, Bilo MB, Brockow K, Fernandez-Rivas M, Santos AF, Zolkipli ZQ, Bellou A, Bindslev-Jensen C, Cardona V, Clark AT, Demoly P, Dubois AEJ, Dunn Galvin A, Eigenmann P, Halken S, Harada L, Lack G, Jutel M, Niggemann B, Rueff F, Timmermans F, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Werfel T, Dhami S, Panesar S, Sheikh A, on behalf of EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12437.

Panesar SS, Javad S, de Silva D, Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, Bilò MB, Cardona V, Dubois AEJ, DunnGalvin A, Eigenmann P, Fernandez-Rivas M, Halken S, Lack G, Niggemann B, Santos AF, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Zolkipli ZQ, Sheikh A, on behalf of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Group. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013;68:1353–61.

Neugut AI, Ghatak AT, Miller RL. Anaphylaxis in United States: an investigation into its epidemiology. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(1):15–21.

Ansotegui IJ, Sánchez-Borges M, Cardona V. Current trends in prevalence and mortality of anaphylaxis. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2016;3:205.

Tejedor Alonso MA, Moro Moro M, Múgica García MV. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(6):1027–39.

Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, et al. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:477–80.

Simons FER, Ardusso LRF, Bilo MB, et al. World Allergy Organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J. 2011;4:13–37.

Brown SG, Mullins RJ, Gold MS. Anaphylaxis: diagnosis and management. Med J Aust. 2006;185:283–9.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Goldberg BJ, Akdis CA, Papadopoulos NG, Demoly P. Categorization of allergic disorders in the new World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:42.

Tanno LK, Ganem F, Demoly P, Toscano CM, Bierrenbach AL. Undernotification of anaphylaxis deaths in Brazil due to difficult coding under the ICD-10. Allergy. 2012;67:783–9.

Demoly P, Tanno LK, Akdis CA, Lau S, Calderon MA, Santos AF, et al. Global classification and coding of hypersensitivity diseases—an EAACI—WAO survey, strategic paper and review. Allergy. 2014;69:559–70.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Goldberg BJ, Gayraud J, Bircher AJ, Casale T, et al. Constructing a classification of hypersensitivity/allergic diseases for ICD-11 by crowdsourcing the allergist community. Allergy. 2015;70:609–15.

Tanno LK, Calderon M, Papadopoulos NG, Demoly P. Mapping hypersensitivity/allergic diseases in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11: cross-linking terms and unmet needs. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:20.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Demoly P, on behalf the Joint Allergy Academies. Optimization and simplification of the allergic and hypersensitivity conditions classification for the ICD-11. Allergy. 2016;71(5):671–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12834.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Demoly P, on behalf the Joint Allergy Academies. New allergic and hypersensitivity conditions section in the International Classification of Diseases-11. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8(4):383–8. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2016.8.4.383.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Papadopoulos NG, Sanchez-Borges M, Moon HB, Sisul JC, Jares EJ, Sublett JL, Casale T, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Surveying the new allergic and hypersensitivity conditions chapter of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11. Allergy. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12945.

Tanno LK, Calderon M, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Supporting the validation of the new allergic and hypersensitivity conditions section of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases-11. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016;6(3):149–56.

Tanno LK, Bierrenbach AL, Calderon MA, Sheikh A, Simons FE, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Decreasing the under notification of anaphylaxis deaths in Brazil through the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 revision. Allergy. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13006.

Tanno LK, Calderon M, Sublett JL, Casale T, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Smoothing the transition from International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification to International Classification of Diseases, eleventh revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.06.024.

Tanno LK, Simons FE, Annesi-Maesano I, Calderon MA, Aymé S, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Fatal anaphylaxis registries data support changes in the who anaphylaxis mortality coding rules. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):8.

Tanno LK, Simons FER, Cardona V, Calderon M, Sanchez-Borges M, Sisul JC, Moon HB, Sublett JL, Casale T, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Applying prevention concepts to anaphylaxis: a call for worldwide availability of adrenaline auto-injectors. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:1108–14.

World Health Organization. ICD-11 beta draft website. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/l-m/en. Accessed Oct 2016.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases website http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed Nov 2016.

World Health Organization. ICD-10 version 2016 website. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en. Accessed Nov 2016.

Orphanet website, rare diseases page. http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease.php?lng=EN. Accessed July 2016.

Aymé S, Bellet B, Rath A. Rare diseases in ICD11: making rare diseases visible in health information systems through appropriate coding. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;26(10):35.

Tanno LK, Molinari N, Bruel S, Bourrain JL, Calderon MA, Aubas P, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Field-testing the new anaphylaxis’ classification for the WHO International Classification of Diseases-11 revision. Allergy. 2017;72(5):820–6.

Loke P, Koplin J, Beck C, Field M, Dharmage SC, Tang ML, Allen KJ. Statewide prevalence of school children at risk of anaphylaxis and rate of adrenaline autoinjector activation in Victorian government schools, Australia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):529–35.

Beyer K, Eckermann O, Hompes S, Grabenhenrich L, Worm M. Anaphylaxis in an emergency setting elicitors, therapy and incidence of severe allergic reactions. Allergy. 2012;67:1451–6.

Buka RJ, Crossman RJ, Melchior CL, Huissoon AP, Hackett S, Dorrian S, Cooke MW, Krishna MT. Anaphylaxis and ethnicity: higher incidence in British South Asians. Allergy. 2015;70:1580–7.

Campbell RL, Bashore CJ, Lee S, Bellamkonda VR, Li JT, Hagan JB, et al. Predictors of repeat epinephrine administration for emergency department patients with anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(4):576–84.

Cetinkaya F, Incioglu A, Birinci S, Karaman BE, Dokucu AI, Sheikh A. Hospital admissions for anaphylaxis in Istanbul, Turkey. Allergy. 2013;68:128–30.

Gibbison B, Sheikh A, McShane P, Haddow C, Soar J. Anaphylaxis admissions to UK critical care units between 2005 and 2009. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(8):833–9.

Grunau BE, Li J, Yi TW, Stenstrom R, Grafstein E, Wiens MO, et al. Incidence of clinically important biphasic reactions in emergency department patients with allergic reactions or anaphylaxis. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(6):736–44.

Harduar-Morano L, Simon MR, Watkins S, Blackmore C. A population-based epidemiologic study of emergency department visits for anaphylaxis in Florida. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):594–600.

Jeppesen AN, Christiansen CF, Frøslev T, Sørensen HT. Hospitalization rates and prognosis of patients with anaphylactic shock in Denmark from 1995 through 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1143–7.

Kimchi N, Clarke A, Moisan J, Lachaine C, La Vieille S, Asai Y, et al. Anaphylaxis cases presenting to primary care paramedics in Quebec. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2015;3(4):406–10.

Lee S, Hess EP, Lohse C, Gilani W, Chamberlain AM, Campbell RL. Trends, characteristics, and incidence of anaphylaxis in 2001–2010: a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.029.

Mullins RJ, Dear KB, Tang ML. Time trends in Australian hospital anaphylaxis admissions in 1998–1999 to 2011–2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):367–75.

Alonso MA, García MV, Hernández JE, Moro MM, Ezquerra PE, Ingelmo AR, et al. Recurrence of anaphylaxis in a Spanish series. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23(6):383–91.

Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, Sampson HA, Schwartz LB, Zitt M, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461–7.

Worm M, Moneret-Vautrin A, Scherer K, Lang R, Fernandez-Rivas M, Cardona V, Kowalski ML, Jutel M, Poziomkowska-Gesicka I, Papadopoulos NG, Beyer K, Mustakov T, Christoff G, Bilo MB, Muraro A, Hourihane JOB, Grabenhenrich LB. First European data from the network of severe allergic reactions (NORA). Allergy. 2014;69:1397–404.

Turner PJ, Gowland MH, Sharma V, Ierodiakonou D, Harper N, Garcez T, et al. Increase in anaphylaxis-related hospitalizations but no increase in fatalities: an analysis of United Kingdom national anaphylaxis data, 1992–2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(4):956–63.

Authors’ contributions

LKT and PD contributed to the construction of the document (designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript). ALB and NM supported the discussion of concepts and reviewed the manuscript. FERS, TC, VC, BY-HT, NGP, MAC, MW and Y-SC contributed to tuning the document and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the representatives of the ICD-11 Revision Project with whom we have been carrying on fruitful discussions, helping us to refine the classification presented here: Robert Jakob, Linda Best, Nenad Kostanjsek, Robert J. G. Chalmers, Jeffrey Linzer, Linda Edwards, Ségolène Ayme, Bertrand Bellet, Rodney Franklin, Matthew Helbert, August Colenbrander, Satoshi Kashii, Paulo E. C. Dantas, Christine Graham, Ashley Behrens, Julie Rust, Megan Cumerlato, Tsutomu Suzuki, Mitsuko Kondo, Hajime Takizawa, Nobuoki Kohno, Soichiro Miura, Nan Tajima and Toshio Ogawa.

Joint Allergy Academies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI), European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), World Allergy Organization (WAO), American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), Asia Pacific Association of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology (APAAACI), Latin American Society of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (SLAAI).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ana Luiza Bierrenbach, Bernard Y. Thong, Nicolas Molinari, Yoon-Seok Chang, Thomas Casale: have no competing interests. Luciana Kase Tanno and Pascal Demoly received an unrestricted AstraZeneca ERS-16-11927 Grant and from MEDA Pharma through CHRUM administration. Luciana Kase Tanno is the allergy representative of the WHO Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee for International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 and other WHO classifications. Pascal Demoly: has received honoraria for consultation and lectures from ALK, Circassia, Stallergèns Greer, Allergopharma, ThermofisherScientific, Meda, Ménarini and is president of the French Allergy Federation. F. Estelle R. Simons: member, Medical Advisory Boards of ALK, Mylan, and Sanofi. Victoria Cardona: has received fees as an advisor and speaker for ALK. M. Calderon: has received honorarium in Advisory Boards for ALK and Hal-Allergy, as speaker for ALK, Merck and Stallergenes-Greer. Margitta Worm: has received honoraria for consultation and lectures from Meda, ALK, and Allergopharma.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. The ICD-11 beta draft and Pubmed platforms are open to the public.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was conducted with support from AstraZeneca, as an unrestricted AstraZeneca ERS-16-11927 Grant and from MEDA Pharma through CHRUM administration.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanno, L.K., Bierrenbach, A.L., Simons, F.E.R. et al. Critical view of anaphylaxis epidemiology: open questions and new perspectives. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 14, 12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0234-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0234-0