Abstract

Background

We previously identified four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subgroups with increasingly higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau). These subgroups included individuals across the cognitive spectrum, suggesting p-tau subgroups could reflect distinct biological changes in AD, rather than disease severity. Therefore, in the current study, we further investigated which potential processes may be related with p-tau subgroups, by comparing individuals on CSF markers for presynaptic structure [vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2)], postsynaptic structure [neurogranin (NRGN)], axonal damage [neurofilament light (NfL)], and amyloid production [beta-secretase 1 (BACE1) and amyloid-beta 1–40 (Aβ40)].

Methods

We selected 348 amyloid-positive (A+) individuals (53 preclinical, 102 prodromal, 193 AD dementia) and 112 amyloid-negative (A−) cognitively normal (CN) individuals from the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort (ADC). Individuals were labeled according to their p-tau subgroup (subgroup 1: p-tau ≤ 56 pg/ml; subgroup 2: 57–96 pg/ml; subgroup 3: 97–159 pg/ml; subgroup 4: > 159 pg/ml). CSF protein levels were measured with ELISA (NRGN, BACE1, Aβ40, NfL) or single-molecule array (Simoa) (VAMP2). We tested whether protein levels differed between the p-tau subgroups within A+ individuals with linear models corrected for age and sex and whether disease stage influenced these relationships.

Results

Among A+ individuals, higher p-tau subgroups showed a higher percentage of AD dementia [subgroup 1: n = 41/94 (44%); subgroup 2: n = 81/147 (55%); subgroup 3: n = 59/89 (66%); subgroup 4: n = 7/11 (64%)]. Relative to controls, subgroup 1 showed reduced CSF levels of BACE1, Aβ40, and VAMP2 and higher levels of NfL. Subgroups 2 to 4 showed gradually increased CSF levels of all measured proteins, either across the first three (NfL and Aβ40) or across all subgroups (VAMP2, NRGN, BACE1). The associations did not depend on the clinical stage (interaction p-values ranging between 0.19 and 0.87).

Conclusions

The results suggest that biological heterogeneity in p-tau levels in AD is related to amyloid metabolism and synaptic integrity independent of clinical stage. Biomarkers reflecting amyloid metabolism and synaptic integrity may be useful outcome measures in clinical trials targeting tau pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

One of the main pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins into tangles in the brain. The burden of tau pathology is associated with cognitive decline [1]. Tau protein concentrations can be measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as total tau (t-tau) or tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau). While both t-tau and p-tau are used as core AD biomarkers in the research framework’s definition of AD [2], p-tau levels are considered to be more specific for neurofibrillary tangles [2] and to differentiate AD from other neurodegenerative diseases with higher specificity [3]. Usually, a single cutpoint is used to separate normal and abnormal p-tau values [2]. However, we have recently identified four subgroups with increasingly high CSF p-tau values [4]. The subgroups included individuals across the clinical spectrum, and most individuals remained in the same p-tau subgroup over time, suggesting that p-tau subgroups may reflect different underlying pathophysiological processes.

Previous studies have found that in addition to amyloid and tau pathology, multiple additional biological processes are involved in AD, including, e.g., amyloid homeostatic changes [5], synaptic dysfunction [6,7,8], and axonal damage [9]. Changes in these processes can be investigated by measuring the levels of biomarkers in CSF. Amyloid production is reflected, among others, by levels of beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1). BACE1 is part of the amyloidogenic pathway producing amyloid-beta 1–42 (Aβ42) [10]. In previous studies, BACE1 levels in CSF were increased in AD-type dementia relative to controls [11] and correlated with t-tau and p-tau levels [12, 13]. Amyloid-beta 1–40 (Aβ40) is another biomarker reflecting amyloid production and is considered to reflect overall production of amyloid-beta species [14]. Aβ40 levels were shown to correlate with p-tau levels in AD [10], but results conflicted whether Aβ40 levels are increased in AD-type dementia relative to controls [9, 10]. Synaptic integrity is reflected by biomarkers such as vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) and neurogranin (NRGN). VAMP2 is a presynaptic protein involved in neurotransmitter release [8, 15], and a previous study showed its levels correlate with t-tau levels and are increased in early stages of AD [16]. NRGN is a postsynaptic protein involved in synaptic signaling and remodeling (see review [17]), and in previous studies, NRGN levels correlated with t-tau and p-tau levels [8, 18,19,20,21,22] and were increased in (early) AD relative to controls [20, 21, 23]. Finally, levels of the axonal structural protein neurofilament light (NfL) increase in CSF with axonal damage [24] and are correlated with t-tau and p-tau levels [25]. Levels of NfL are increased in prodromal AD and AD-type dementia [19], but also in other neurodegenerative diseases [19, 24], and NfL is therefore considered a non-specific marker of neuronal damage.

Since previous studies showed that biomarkers of amyloid metabolism, synaptic integrity, and axonal damage correlate with CSF tau values, we hypothesized that p-tau subgroups in individuals with AD may differ in these processes. We investigated in individuals with AD the relationships of p-tau subgroups with proteins reflecting amyloid production (BACE1, Aβ40), synaptic function (VAMP2, NRGN), and axonal damage (NfL) and tested if such associations depended on clinical stage. Finally, since an increase in tau is observed in normal aging as well [26], we tested if protein levels were similarly associated with p-tau in cognitively normal (CN) individuals with normal amyloid.

Methods

Study cohort and selection criteria

The present analyses were conducted as part of the redefining AD study, which aims to explain biological heterogeneity in AD and is described in this paper for the first time. We selected individuals from the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort (ADC) [27] when they had normal cognition and normal CSF amyloid or when they had abnormal amyloid (A+) across the clinical AD spectrum (i.e., normal cognition (preclinical AD), mild cognitive impairment (prodromal AD), and AD-type dementia). Individuals further needed to have available CSF stored in our biobank. This resulted in a selection of 453 individuals. The study participants visited our memory clinic between September 2004 and March 2018.

As described in more detail elsewhere [27], most individuals received a standardized neuropsychological test battery with at least one test per cognitive domain and completed the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [28]. In addition, participants underwent physical and neurological investigation, laboratory tests, and imaging [electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)]. The diagnosis was made by a multidisciplinary team blinded to the patients’ CSF Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau results. For MCI, Petersen’s criteria [29] were used until the start of 2012, after which the criteria were used of the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) [30]. For AD dementia, the criteria were used of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) [31]. Individuals who did not meet the criteria for MCI, AD, other dementias, or any psychiatric or neurologic disease were considered CN. All study participants gave written informed consent for the use of their clinical data and CSF for research purposes. The ADC study was approved by the ethical review board of the VU University Medical Center.

Collection of CSF by lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture was performed using a 25-gauge needle and a syringe, and CSF was collected in 10-mL polypropylene tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) [32, 33]. The CSF was centrifuged at 1800g at 4 °C for 10 min within 2 h of the lumbar puncture, transferred to new polypropylene tubes, and stored at − 20 °C for routine analysis of core AD biomarkers, or stored in the biobank at − 80 °C.

Amyloid, t-tau, and p-tau measurements

Levels of amyloid, t-tau, and p-tau in CSF were measured with Innotest on a routine basis [34]. We used drift-corrected historical amyloid values, because values in ADC showed an upward drift across time [35], and used a cutpoint of 813 pg/ml to dichotomize amyloid status. We defined p-tau subgroups using previously derived cutpoints [4]: subgroup 1 (p-tau ≤ 56 pg/ml), subgroup 2 (p-tau 57–96 pg/ml), subgroup 3 (p-tau 97–159 pg/ml), and subgroup 4 (p-tau > 159 pg/ml). We additionally determined dichotomous t-tau and p-tau status based on the lowest of our previously derived cutpoints [4], with levels considered abnormal at p-tau > 56 pg/ml and t-tau > 349 pg/ml.

Protein measurements

Levels of BACE1, Aβ40, and NRGN in CSF were measured with ELISA assays (EUROIMMUN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Levels of VAMP2 were measured with single-molecule array (Simoa) technology (Quanterix Corp, Billerica, USA) using a prototype assay developed by ADx NeuroSciences (Belgium), and levels of NfL were measured with an ELISA assay developed by ADx NeuroSciences (Belgium). The novel NfL assay correlated well (Spearman R = 0.952) with the widely used NF-Light ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) (Das et al., manuscript submitted). For VAMP2, we excluded 21 measurements with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 20 or higher, and 22 samples for which one of the two measurements failed. For NfL, we excluded 3 measurements which were lower than the limit of detection. NRGN, BACE1, and Aβ40 data had no missing values.

Determination of APOE genotypes

APOE genotypes were determined in 10 mL EDTA blood from which DNA was isolated with the QIAamp DNA blood isolation kit (Qiagen), followed by genotyping with the Light Cycler APOE mutation detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany).

Statistics

Group differences between p-tau subgroups in demographic variables were tested with ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, or chi-square tests, followed by post hoc subgroup comparisons with t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or chi-square tests as applicable. We next tested if p-tau subgroups showed different protein levels among individuals with AD, first based on raw protein levels. As raw protein levels were non-normally distributed, we tested if the protein levels differed depending on p-tau subgroups with Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests, and used Wilcoxon rank sum tests to compare all p-tau subgroups. To further test the subgroup differences adjusting for age and sex with linear models, we first natural log-transformed and then Z-scored protein levels relative to controls (i.e., CN individuals with normal amyloid, t-tau, and p-tau). All models had as outcome protein level and included as predictors p-tau subgroup, age, and sex. All effect sizes (i.e., estimated protein levels per p-tau subgroup and differences between p-tau subgroups) were adjusted for the other predictors. In all models, biomarker normal controls were used as a reference. We first constructed linear models across all individuals to test whether the analyzed proteins differed between p-tau subgroups. Next, we constructed linear models that additionally included an interaction term between p-tau subgroup and cognitive stage. We tested if p-tau subgroups showed an interaction with cognitive stage (considered at interaction p-value < 0.1) and estimated marginalized mean protein levels in each cognitive stage. Finally, we labeled CN amyloid-negative individuals as belonging to p-tau subgroups. A minority of these individuals had abnormal p-tau levels (p-tau subgroups 2 or 3) and could therefore be considered to have suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology (SNAP). We performed exploratory analyses if p-tau subgroups show differences in protein levels in CN amyloid-negative individuals by also constructing linear models in this group. Post hoc group comparisons were p-value adjusted with the false discovery rate (FDR) method (for Wilcoxon rank sum tests used on raw protein levels) or with the Sidak method (for contrasts between p-tau subgroups in linear models) and considered significant at an adjusted p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.1 “Action of the Toes,” and estimated marginal means were computed with the R package “emmeans” v1.4.

Results

We included a total of 453 individuals, of whom 112 were amyloid-negative CN individuals (98 controls and 14 individuals with t-tau or p-tau levels indicative of SNAP) and of whom 341 were A+ across different clinical stages (preclinical AD (n = 51), prodromal AD (n = 102), AD dementia (n = 188); full demographic characterization in Table 1). Compared to amyloid-negative individuals, A+ individuals showed a higher proportion of APOE ε4 carriers and were on average older, with the oldest average age in prodromal AD.

Demographic comparisons of p-tau subgroups

We used our previously identified cutpoints to define four p-tau subgroups in our data. In total, of all A+ individuals across the AD clinical spectrum, 94 individuals fell in subgroup 1 (p-tau ≤ 56 pg/ml), 147 individuals in subgroup 2 (p-tau 57–96 pg/ml), 89 individuals in subgroup 3 (p-tau 97–159 pg/ml), and 11 individuals in subgroup 4 (p-tau > 159 pg/ml). A full demographic and biological characterization of p-tau subgroups is provided in Table 2. Relative to the first p-tau subgroup, the third p-tau subgroup showed an older age. P-tau subgroup 3 showed a higher proportion of women compared to subgroups 1–2. Higher p-tau subgroups tended to show worse MMSE scores in a stepwise manner. Overall, the relative proportion of preclinical and prodromal AD was similar for the p-tau subgroups, and the proportion of AD dementia was higher in subgroups 2–4 than in subgroup 1.

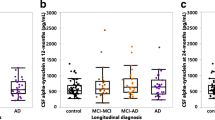

P-tau subgroups associated with amyloid production and synaptic biomarkers in AD

Next, we set out to compare the p-tau subgroups in other AD-related processes, including amyloid metabolism, synaptic integrity, and axonal damage (see overview visualization in Fig. 1). Compared to controls, p-tau subgroup 1 showed higher levels of NfL but lower levels of BACE1, Aβ40, and VAMP2 (Fig. 2, Table 2). Subgroups 2 to 4 showed stepwise increases in CSF levels of BACE1, VAMP2, NRGN, and Aβ40, of which NRGN showed the largest differences between p-tau subgroups (Fig. 2, Table 2). NfL levels showed stepwise increases across the first three p-tau subgroups and did not reach significance when comparing subgroups 3 and 4. The results remained similar when we repeated the analyses on natural log-transformed and standardized variables and corrected for age and sex effects (Table 3). Repeating analyses including an interaction effect in the models showed that these associations with p-tau subgroups did not differ for disease severity (all interaction p-value > 0.1, Table 4, Fig. 3).

Overview of the study design. Among amyloid abnormal individuals, previously established p-tau subgroups [4] were compared in markers reflecting other AD-related processes: Aβ40 and BACE1 (reflecting amyloid metabolism), NfL (reflecting axonal damage), and VAMP2 and NRGN (reflecting synaptic integrity). The density distribution of p-tau subgroups was adapted from previous research [4]. Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; APP, amyloid precursor protein; BACE1, beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; γ-secr., γ-secretase; NfL, neurofilament light; NRGN, neurogranin; VAMP2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

P-tau subgroups differ in proteins reflecting amyloid production, synaptic damage, and axonal damage. Controls were cognitively normal individuals with normal CSF amyloid, t-tau, and p-tau. Protein levels were Z-scored relative to controls. The box of the boxplot indicates the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile, and whiskers indicate the 1.5× interquartile range. Arrows indicate the protein measurements outside of the y-axis. Differences in the protein levels between p-tau subgroups, and between p-tau subgroups and controls, were calculated with linear models corrected for age and sex. p-values were adjusted for the multiple comparisons between p-tau subgroups with the Sidak method. BACE1, beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; NfL, neurofilament light; VAMP2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2; NRGN, neurogranin. *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001; n.s., not significant

Associations of p-tau subgroups with protein levels were independent of clinical stage. Protein level differences are shown stratified for clinical stage: preclinical AD, prodromal AD, and AD dementia. Controls were cognitively normal individuals with normal CSF amyloid, t-tau, and p-tau. Protein levels were Z-scored relative to controls. The box of the boxplot indicates the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile, and whiskers indicate the 1.5× interquartile range. Arrows indicate the protein measurements outside of the y-axis. Differences between p-tau subgroups in the protein levels were calculated with linear models adjusted for age, sex, diagnostic group (controls, preclinical AD, prodromal AD, and AD dementia), and the interaction between protein level and diagnostic group. p-values were adjusted for the multiple comparisons between p-tau subgroups with the Sidak method. BACE1, beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; NfL, neurofilament light; VAMP2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2; NRGN, neurogranin. *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001; n.s., not significant

Associations of p-tau subgroups with protein levels in CN amyloid-negative individuals

Finally, we explored if CN amyloid-negative individuals also show the pattern of increased markers of amyloid production and synaptic damage with higher p-tau subgroups. A minority of these individuals fell in the second p-tau subgroup (n = 7/112, 6%) or third p-tau subgroup (n = 2/112, 2%). As amyloid-negative individuals with higher p-tau may be in a pre-amyloid stage, we tested if Aβ42 levels differed between p-tau subgroups, but found no differences (Table 5). Levels of BACE1, Aβ40, VAMP2, and NRGN were increased in p-tau subgroup 2 and 3 relative to subgroup 1, while NfL did not differ between the p-tau subgroups (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Associations of p-tau subgroups with protein levels in CN amyloid-negative individuals. CN amyloid-negative individuals included both individuals with normal t-tau and p-tau (controls) and individuals with abnormal t- or p-tau (suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathology or SNAP). Protein levels were Z-scored relative to controls. The box of the boxplot indicates the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile, and whiskers indicate the 1.5× interquartile range. Arrows indicate the protein measurements outside of the y-axis. Differences between p-tau subgroups in the protein levels were calculated with linear models adjusted for age and sex. p-values were adjusted for the multiple comparisons between p-tau subgroups with the Sidak method. BACE1, beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; NfL, neurofilament light; VAMP2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2; NRGN, neurogranin. *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001; n.s., not significant

Discussion

We found that among individuals with AD, the lowest p-tau subgroup showed reduced levels of amyloid production biomarkers (BACE1 and Aβ40) and a presynaptic marker (VAMP2) relative to controls. Subgroups with gradually higher p-tau values (subgroups 2–4) showed stepwise increases in BACE1, Aβ40, VAMP2, a postsynaptic biomarker (NRGN), and, to a more moderate extent, an axonal damage marker (NfL). As these associations were independent of clinical stage, and were similar for amyloid-negative CN individuals (apart from NfL which did not show differences in this group), p-tau subgroups may, in addition to disease severity, reflect biological subtypes of AD that have distinct profiles of amyloid metabolism and synaptic integrity markers, apparently already when cognition is still unimpaired.

We found that p-tau subgroups 2–4 had increasingly higher CSF markers of amyloid production and synaptic integrity markers, which is in line with studies that reported continuous associations of tau with biomarkers reflecting these processes (i.e., Aβ40 [36] and BACE1 [12, 13], NRGN [8, 18,19,20,21,22], and VAMP2 [16]). A previous study also showed tau and amyloid metabolism may have overlapping causal mechanisms, as in cognitively intact monozygotic twins, amyloid production markers in one twin were related to p-tau levels of the other twin [37]. A similar result was observed in APPPS1 mice, which do not develop tau pathology but nonetheless showed increasing CSF p-tau levels over time which closely corresponded to increasing amyloid load [38]. Our results provide further support for the idea that processes of tau and amyloid metabolism may be linked. Since in normal cognition high tangle burden is not expected, this suggests that p-tau levels in CSF may reflect other pathophysiological aspects of AD as well. Subgroup 1 consisted mostly of individuals with normal CSF p-tau, and also included individuals with dementia, which are thought to have the highest pathological tau burden. In the current research framework, AD is defined based on abnormal amyloid and tau biomarkers [2]. This framework suggests that the subgroup with normal p-tau CSF levels and abnormal amyloid (i.e., A+T−) do not have AD, but AD pathological change. However, previous studies found that up to 30% of individuals with a pathological diagnosis of AD, can show normal CSF p-tau levels [39]. Possibly, normal p-tau levels may indicate a biological subtype of AD, since individuals in this subgroup showed compared to controls a different pattern of alterations in CSF markers. For example, VAMP2 and amyloid metabolism markers were decreased compared to controls, whereas these markers were increased in subgroups 2–4. This was not a generic effect, because NfL was increased in subgroup 1 compared to controls. This suggests that this tau subgroup shows a distinct underlying pathophysiology that is related to lower p-tau levels in CSF. A recent CSF proteomic study suggests that A+ individuals with normal tau levels show involvement in blood-brain barrier dysfunction, and indications of decreased amyloid metabolism as well as lower levels of proteins associated with neuronal plasticity [39]. Potentially, the lowest tau subgroup could differ in additional processes, e.g., in another study, A+ individuals with normal tau levels showed reductions in immune-related proteins [40]. Together, our results provide further evidence that the four subgroups we observed in CSF p-tau levels reflect, at least in part, distinct pathophysiological processes. Further studies should aim to investigate these processes in more detail, e.g., through a combined CSF and pathology approach.

Compared to the other markers, we observed that the increases in NfL levels with higher p-tau subgroups were less pronounced and did not differ between the third and fourth p-tau subgroup. Potentially, associations of p-tau subgroups with amyloid and synaptic markers may be stronger compared to NfL, because structural axonal loss occurs downstream of changes in amyloid production and synaptic damage [22, 41, 42]. Overall, our results suggest focusing on amyloid and synaptic processes rather than axonal damage may be promising to further characterize p-tau subgroups.

Finally, we observed that levels of amyloid production markers were increased with higher p-tau subgroups even in amyloid-negative CN individuals. A previous study showed that higher levels of markers for amyloid production were associated with a steeper (i.e., more abnormal) decline in Aβ42 levels [43]. Possibly, such high amyloid metabolism markers in combination with high tau levels may represent a very early stage of AD, and future studies should aim to test this hypothesis in a longitudinal design with repeated CSF sampling.

There is currently one drug candidate in a phase III clinical trial that targets tau aggregation (TRx0237, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03446001), and several additional drug candidates targeting tau are currently undergoing phase I and II trials [44, 45]. Our p-tau cutoffs could be useful to select individuals with high p-tau levels as participants for clinical trials of drug candidates targeting tau, who may hypothetically benefit most from lowering their p-tau levels. Additionally, including amyloid production and synaptic markers as exploratory trial outcomes could be insightful to show if reductions in p-tau will also normalize markers of these processes.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was that we analyzed the p-tau subgroups cross-sectionally. Although we previously showed in ADNI that the majority of individuals remain in their p-tau subgroup over time [4], it remains to be determined if levels of the other proteins remain similarly constant. Another potential limitation of the present study is that we selected 5 proteins a priori. More proteins reflecting other biological processes may be involved that could be different as well, and future studies should investigate this using, e.g., proteomic approaches. Subgroup 4 had a relatively small sample size, and follow-up studies in even larger sample sizes will be useful to replicate the findings. Nonetheless, a strength of this study was that we had an overall large sample size of 453 individuals across the AD clinical spectrum and CN amyloid-negative individuals from a well-defined cohort, from whom CSF was collected under standardized biobanking conditions. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the first study with a large sample size to validate that VAMP2 is associated with AD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that subgroups of individuals with increasingly high p-tau showed stepwise increases in proteins reflecting amyloid production and synaptic damage. Our data suggest that heterogeneity in tau pathology is related to differences in amyloid production and synaptic processes, which seems independent of the clinical stage. P-tau subgroups might be useful as a stratification tool to select individuals with AD, including those still in preclinical and prodromal stages, as participants for clinical trials targeting tau aggregation.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A+:

-

Amyloid abnormal

- Aβ40:

-

Amyloid-beta 1–40

- Aβ42:

-

Amyloid-beta 1–42

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADC:

-

Amsterdam Dementia Cohort

- APOE :

-

Apolipoprotein E

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1:

-

Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

- CN:

-

Cognitively normal

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NfL:

-

Neurofilament light

- NIA-AA:

-

National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association

- NINCDS-ADRDA:

-

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association

- NRGN:

-

Neurogranin

- p-tau:

-

Tau phosphorylated at threonine 181

- SIMOA:

-

Single-molecule array

- SNAP:

-

Suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology

- t-tau:

-

Total tau

- VAMP2:

-

Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

References

Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, Liu H, Davis DG, Mendiondo MS, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort: neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1136–46.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dementia. 2018;14:535–62.

Riemenschneider M, Wagenpfeil S, Vanderstichele H, Otto M, Wiltfang J, Kretzschmar H, et al. Phospho-tau/total tau ratio in cerebrospinal fluid discriminates Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease from other dementias. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:343–7.

Duits FH, Wesenhagen KEJ, Ekblad L, Wolters E, Willemse EAJ, Scheltens P, et al. Four subgroups based on tau levels in Alzheimer’s disease observed in two independent cohorts. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1).

Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–30.

Scheff SW, DeKosky ST, Price DA. Quantitative assessment of cortical synaptic density in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11:29–37.

Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, Mufson EJ. Hippocampal synaptic loss in early Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1372–84.

Nilsson J, Gobom J, Sjödin S, Brinkmalm G, Ashton NJ, Svensson J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker panel for synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dementia. 2021;13(1).

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Öhrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:673–84.

Vassar R. β-Secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–41.

Hampel H, Vassar R, de Strooper B, Hardy J, Willem M, Singh N, et al. The β-secretase BACE1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2020:745–56.

Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, Hansson O, Wu G, Sankaranarayanan S, Andersson ME, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid BACE1 activity in incipient Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1102–7.

Timmers M, Barão S, Van Broeck B, Tesseur I, Slemmon J, De Waepenaert K, et al. BACE1 dynamics upon inhibition with a BACE inhibitor and correlation to downstream Alzheimer’s disease markers in elderly healthy participants. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:1437–49.

Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lee D, Keim P, Lieberburg I, Schenk DB. Rapid communication: characterization of β-amyloid peptide from human cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1965–8.

Margiotta A. Role of SNAREs in neurodegenerative diseases. Cells. 2021;10:991.

Lleó A, Núñez-Llaves R, Alcolea D, Chiva C, Balateu-Paños D, Colom-Cadena M, et al. Changes in synaptic proteins precede neurodegeneration markers in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18:546–60.

Lista S, Hampel H. Synaptic degeneration and neurogranin in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. 2016;17:47–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2016.1204234.

Janelidze S, Hertze J, Zetterberg H, Waldö ML, Santillo A, Blennow K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin and YKL-40 as biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:12–20.

Mattsson N, Insel PS, Palmqvist S, Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Weiner M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, neurogranin, and neurofilament light in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:1184–96.

Kvartsberg H, Duits FH, Ingelsson M, Andreasen N, Öhrfelt A, Andersson K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the synaptic protein neurogranin correlates with cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1180–90.

Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Skillbäck T, Törnqvist U, Andreasson U, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin: relation to cognition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138:3373–85.

Van Hulle C, Jonaitis EM, Betthauser TJ, Batrla R, Wild N, Kollmorgen G, et al. An examination of a novel multipanel of CSF biomarkers in the Alzheimer’s disease clinical and pathological continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:431–45.

Milà-Alomà M, Brinkmalm A, Ashton NJ, Kvartsberg H, Shekari M, Operto G, et al. CSF synaptic biomarkers in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer disease and their association with MRI and PET: a cross-sectional study. Neurology. 2021;97:2065–78.

Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, Tijms BM, Teunissen CE, Alvarez-Cermeño JC, et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:1035–48.

Jin M, Cao L, Dai YP. Role of neurofilament light chain as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a correlative meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:254.

Toledo JB, Zetterberg H, van Harten AC, Glodzik L, Martinez-Lage P, Bocchio-Chiavetto L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker in cognitively normal subjects. Brain. 2015;138:2701–15.

van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Amsterdam Dementia Cohort: performing research to optimize care. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:1091–111.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004:183–94.

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–9.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44.

Engelborghs S, Niemantsverdriet E, Struyfs H, Blennow K, Brouns R, Comabella M, et al. Consensus guidelines for lumbar puncture in patients with neurological diseases. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:111–26.

Babapour Mofrad R, Bouwman FH, Slot RER, Timmers T, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, et al. Lumbar puncture in patients with neurologic conditions. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:108–10.

Jongbloed W, Kester MI, van der Flier WM, Veerhuis R, Scheltens P, Blankenstein MA, et al. Discriminatory and predictive capabilities of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and multiplex platforms in a longitudinal Alzheimer’s disease study. Alzheimers Dementia. 2013;9:276–83.

Tijms BM, Willemse EAJ, Zwan MD, Mulder SD, Visser PJ, van Berckel BNM, et al. Unbiased approach to counteract upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β 1–42 analysis results. Clin Chem. 2018;64:576–85.

Lehmann S, Dumurgier J, Ayrignac X, Marelli C, Alcolea D, Ormaechea JF, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid A beta 1–40 peptides increase in Alzheimer’s disease and are highly correlated with phospho-tau in control individuals. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:1–12.

Konijnenberg E, Tomassen J, den Braber A, ten Kate M, Yaqub M, Mulder SD, et al. Onset of preclinical Alzheimer disease in monozygotic twins. Ann Neurol. 2021;89:987–1000.

Kaeser SA, Häsler LM, Lambert M, Bergmann C, Bottelbergs A, Theunis C, et al. CSF p-tau increase in response to Aβ-type and Danish-type cerebral amyloidosis and in the absence of neurofibrillary tangles. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;143:287–90.

Visser PJ, Reus LM, Gobom J, Jansen I, Dicks E, van der Lee SJ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau levels are associated with abnormal neuronal plasticity markers in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:1–16.

Meyer P-F, Savard M, Poirier J, Labonté A, Rosa-Neto P, Weitz TM, et al. Bi-directional association of cerebrospinal fluid immune markers with stage of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63:577–90 Available from: http://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-170887. Cited 2018 Oct 25.

Milà-Alomà M, Salvadó G, Gispert JD, Vilor-Tejedor N, Grau-Rivera O, Sala-Vila A, et al. Amyloid beta, tau, synaptic, neurodegeneration, and glial biomarkers in the preclinical stage of the Alzheimer’s continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:1358–71.

Pereira JB, Janelidze S, Ossenkoppele R, Kvartsberg H, Brinkmalm A, Mattsson-Carlgren N, et al. Untangling the association of amyloid-β and tau with synaptic and axonal loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2021;144:310–24.

Tijms BM, Vermunt L, Zwan MD, van Harten AC, van der Flier WM, Teunissen CE, et al. Pre-amyloid stage of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively normal individuals. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:1037–47.

VandeVrede L, Boxer AL, Polydoro M. Targeting tau: clinical trials and novel therapeutic approaches. Neurosci Lett. 2020;731:134919.

Cummings J, Lee G, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Taghva K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2021. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;7:e12179.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kees van Uffelen for the assistance in measuring the samples.

Funding

This work has been supported by the ZonMW Memorabel grant program #733050824 (KW, BMT, and PJV). Research of Alzheimer’s Centre Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is supported by Stichting Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc fonds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KW wrote the draft of the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses. PS led the design of the ADC, from which data were used in this article. LB and PH performed the laboratory analyses. JG, ND, and EV helped to set up and calibrate the VAMP2 assay. All authors made suggestions for the improvement of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the medical ethics committee of the VU University Medical Center (VUmc), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or surrogates.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CT has functioned in advisory boards of Roche, received non-financial support in the form of research consumables from ADx Neurosciences and Euroimmun, performed contract research, or received grants from Probiodrug, Biogen, Eisai, Toyama, Janssen Prevention Center, Boehringer, Axon Neuroscience, EIP farma, PeopleBio, and Roche. PS has received consultancy fees (paid to the university) from AC Immune, Alzheon, Brainstorm Cell, ImmunoBrain Checkpoint, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. Within his university affiliation, he is the PI of studies with AC Immune, FUJI-film/Toyama, IONIS, UCB, and Vivoryon. He is also an employee of Life Sciences Partners Amsterdam. EV is the co-founder of ADx NeuroSciences. JG and ND are employees at ADx Neurosciences. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wesenhagen, K.E.J., Tijms, B.M., Boonkamp, L. et al. P-tau subgroups in AD relate to distinct amyloid production and synaptic integrity profiles. Alz Res Therapy 14, 95 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-01038-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-01038-z