Abstract

Background

Observational studies have suggested that herpesvirus infection increased the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but it is unclear whether the association is causal. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the causal relationship between four herpesvirus infections and AD.

Methods

We performed a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis to investigate association of four active herpesvirus infections with AD using summary statistics from genome-wide association studies. The four herpesvirus infections (i.e., chickenpox, shingles, cold sores, mononucleosis) are caused by varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus type 1, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), respectively. A large summary statistics data from International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project was used in primary analysis, including 21,982 AD cases and 41,944 controls. Validation was further performed using family history of AD data from UK Biobank (27,696 cases of maternal AD, 14,338 cases of paternal AD and 272,244 controls).

Results

We found evidence of a significant association between mononucleosis (caused by EBV) and risk of AD after false discovery rates (FDR) correction (odds ratio [OR] = 1.634, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.092–2.446, P = 0.017, FDR-corrected P = 0.034). It has been verified in validation analysis that mononucleosis is also associated with family history of AD (OR [95% CI] = 1.392 [1.061, 1.826], P = 0.017). Genetically predicted shingles were associated with AD risk (OR [95% CI] = 0.867 [0.784, 0.958], P = 0.005, FDR-corrected P = 0.020), while genetically predicted chickenpox was suggestively associated with increased family history of AD (OR [95% CI] = 1.147 [1.007, 1.307], P = 0.039).

Conclusions

Our findings provided evidence supporting a positive relationship between mononucleosis and AD, indicating a causal link between EBV infection and AD. Further elucidations of this association and underlying mechanisms are likely to identify feasible interventions to promote AD prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The possibility of an infectious etiology for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has long been suspected, including the roles of viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Recent meta-analyses have investigated and suggested that some herpesvirus infections were associated with a higher risk of AD [1, 2], especially the infection of human herpes virus-1 (HSV-1), human herpes virus-6, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). However, the current observational studies are limited by residual, unmeasured confounding, or other biases such as reverse causation and detection bias [3, 4]. It is still unclear whether the associations are causal relationships [5]. Recently, an article has detected EBV-specific T cell receptors in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with AD, which were enhanced in increased antigen-specific clonal expansion of CD8 + T cells in AD [6]. Although this article implied an association between EBV infectivity and AD in a new perspective, their data were still not a direct evidence of causation.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an analytic approach using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) for an exposure. Like randomized control trials, MR analyses reduce confounding and reverse causality due to the random allocation of genotypes from parents to offspring [7]. MR analyses are increasingly used to determine causal effects between potentially modifiable risk factors and the outcomes. A previous MR analysis has highlighted that MR can be used as an initial screening tool for validating the association between infection and AD [8]. Although HSV have been reported to be associated with AD in many epidemiological studies [2, 9], Kwok et al. found no causal association of the HSV infection with cognitive function or late-onset AD using MR analysis [8]. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the potential causality between herpesvirus infections and risk of AD using an unbiased approach. What is more, two-sample MR analysis is an extension in which the effects of the genetic instruments on exposure and outcome are obtained from separate genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [10]. The recent large-scale genome-wide datasets of infections and AD enable us to link four herpesvirus infections (i.e., chickenpox, shingles, cold sores, and mononucleosis) with risk of AD using two-sample MR approach [11, 12].

The four herpesvirus infections involved in the present MR study have been reported to be linked with AD [1, 2], which are mainly caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV), HSV-1, and EBV, respectively. Primary infection of these herpesviruses typically occurs at a young age. Each persists in latent form following resolution of the primary infection and can reactivate once again. Chickenpox results from primary infection of VZV in childhood, while shingles are caused by the reactivation of latent VZV in later life. Cold sores are mainly caused by reactivation of HSV-1. Over 90% of the world’s adult population is chronically infected with EBV. However, primary infections in children are usually asymptomatic. When primary EBV infection occurs later in life, it often results in mononucleosis [13].

In the present study, we adopted the two-sample MR approach to assess the causal associations between four active herpesvirus infections (cold sores, mononucleosis, chickenpox, and shingles) and the risk of AD using summary statistics from GWAS, that is, to evaluate the effects of VZV, HSV-1, and EBV infection in AD risk.

Methods

Exposure GWAS data set

For infections, we used the GWAS summary statistics data from 23andMe cohort [12]. Individuals were included in this GWAS analysis using a set of strict self-reported questionnaires about their history of infection diseases to define phenotypes [12]. Participants were selected for having > 97% European ancestry as determined through an analysis of local ancestry. We focused on four infections (chickenpox, shingles, cold sores, mononucleosis) all caused by members of the human herpesvirus that were discussed in association with AD [1, 2]. The detailed descriptions (age, sex, sample size, etc.) of the GWAS data are presented in Table 1.

Outcome GWAS data set

In primary analysis, we used summary statistics data from a meta-analysis GWAS performed by International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project (IGAP) [11]. IGAP is a large two-stage study based upon GWAS on individuals of European ancestry. Data from stage 1 was used in the present study, including 63,926 individuals (21,982 AD cases and 41,944 cognitively normal controls) from four consortia. Summary details were given in Table 1. We additionally set out to validate our results in a family history of AD data set from UK Biobank [14]. Individuals with one or two parents with AD were defined as having family history of AD, which was ascertained via self-report. In this summary statistics data, an array of 314,278 participants in the UK Biobank were meta-analyzed, including 27,696 cases of maternal AD, 14,338 cases of paternal AD and 272,244 controls.

Instrument identification

Only single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated at genome-wide significance P value (P < 5 × 10−8) with a minor allele frequency greater than 0.01 were considered as potential instruments. Independent SNPs were selected at a threshold of linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 > 0.05 and a distance of 1000 kb. For palindromic SNPs, we aligned strands using allele frequency and discarded palindromic SNP(s) that had minor allele frequency above 0.42. If any SNP was unavailable for an outcome summary data, we used LDlink (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/) API [15, 16] to identified proxy SNPs with a minimum LD r2 = 0.8. Then, exposure–outcome datasets were harmonized. We have considered the palindromic SNPs and checked original datasets to avoid reverse effects. We computed the proportion of variance in the phenotype explained by IV. The strength of the genetic instrument was judged by F-statistics, with a strong instrument defining as an F-statistic > 10 [17]. Lastly, we calculated the statistical power for this MR study with a two-sided type-I error rate α = 0.05 using R code provided by Burgess S [18]. The proportion of variance explained by IVs, F-statistics and power were presented in Additional file 1.

Two-sample MR analysis

For each genetic instrument, the Wald ratio was calculated by dividing the effect size estimate for the association of the variant with the outcome by the corresponding estimate for the association of the variant with the exposure. When more than one SNPs were available, Wald estimates were meta-analyzed using inverse variance weighting (IVW) method. The IVW method will return an unbiased estimate in the absence of horizontal pleiotropy or when horizontal pleiotropy is balanced [19]. All causal estimates were converted to odds ratios (ORs) for the outcome was dichotomous. For exposure with more than three SNPs available (i.e., shingles), we conducted sensitivity analyses using weighted median [20], weighted mode [21], simple mode, MR Egger regression [22], and MR-PRESSO [23]. These methods hold different assumptions at the costs of reduced statistical power. The MR-Egger method is based on the “NO Measurement Error” (NOME) assumption (no measurement error in the SNP exposure effects), which is evaluated by the regression dilution I2GX statistic (i.e., less than 0.9 indicates a violation of NOME) [24]. We used the MR Egger intercept, MR-PRESSO global test, and Cochran Q statistic to test the presence of heterogeneity or directional pleiotropy (i.e., shingles). Moreover, visual inspection of the forest plot, scatter plot, and leave-one-out plot were also used to assess the MR “no horizontal pleiotropy” assumption (see Additional file 6). For exposures with less than three SNP as IV (i.e., chickenpox, cold sores, mononucleosis), we performed another pleiotropy analysis using the Phenoscanner database to check significant associated traits of each SNP prioritized in the present study with phenotypes from previously published GWAS [25, 26].

To correct for multiple comparisons (four exposures), we applied a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rates (FDR) correction. P values below 0.05 but not survived the FDR correction were considered as suggestive of a potential association. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.3, with the MR analysis performed using the “TwoSampleMR” package version 0.5.2 [27, 28].

Results

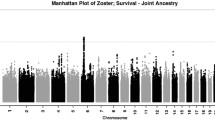

A flow diagram depicting the process of the MR analyses is shown in Fig. 1. The 23andMe cohort identified one SNP for mononucleosis (rs2596465 in HCP5 gene, P = 2.48 × 10−9), two SNP for chickenpox (rs10947050 in RNF39, P = 1.08 × 10−10; rs9266089 in HLA-B, P = 1.00 × 10−10), two SNP for cold sores (rs4360170 in HCP5, P = 3.41 × 10−12; rs885950 in POU5F1, P = 7.47 × 10−13), 15 SNPs for shingles in primary analysis and 13 SNPs in validation (Additional files 2, 3). Summary statistics for the genetic variants of herpesvirus infections and AD are presented in Additional file 3. Additional file 4 shows individual genetic estimates from each of the genetic variants in primary analysis and in validation.

A flow diagram of the process in this Mendelian randomization analysis. AD, Alzheimer disease; ADGC, Alzheimer Disease Genetics Consortium; CHARGE, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium; EADI, The European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative; GERAD/PERADES, Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD/Defining Genetic, Polygenic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium; GWAS, genome-wide association studies; N, number; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism

The estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the Wald ratio or IVW analysis and the numbers of SNPs are presented in Fig. 2. In the primary analysis, Wald ratio showed that the genetically predicted mononucleosis was significantly associated with the risk of AD after FDR correction (OR [95% CI] = 1.634 [1.092, 2.446], P = 0.017, FDR-corrected P = 0.034). The result has been verified in UK Biobank GWAS and yielded similar patterns of effects with P value (OR [95% CI] = 1.392 [1.061, 1.826], P = 0.017).

Using IVW method, genetically predicted cold sores was not associated with risk of AD in primary analysis (OR [95% CI] = 0.959 [0.733, 1.254], P = 0.758) and was not associated with family history of AD in validation (OR [95% CI] = 0.966 [0.738, 1.265], P = 0.802). These findings concur with the results of the previous paper on HSV [8]. Genetically predicted chickenpox showed no association with AD (OR [95% CI] = 0.846 [0.654, 1.094], P = 0.202), but showed suggestive association with the family history of AD in validation (OR [95% CI] = 1.147 [1.007, 1.307], P = 0.039).

In primary analysis, IVW showed that the genetically predicted shingles were significantly associated with the decreased risk of AD (OR [95% CI] = 0.867 [0.784, 0.958], P = 0.005, FDR-corrected P = 0.020). Interestingly, the weighted median and MR-PRESSO methods support this significant association with P < 0.05. However, the estimate of association between shingles and family history of AD was marginally significant in validation (OR [95% CI] = 1.047 [0.995, 1.101], P = 0.075), and the point estimate direction was opposite to primary analysis. The Cochran Q statistic for shingles indicated no notable heterogeneity across instrument SNP effects (P > 0.05; see Additional file 2). The MR Egger intercept test (i.e., I2GX = 0.98) and MR-PRESSO global test for shingles both suggested no horizontal pleiotropy (P > 0.05) in primary analysis and in validation. Additionally, for chickenpox, cold sores, and mononucleosis, we performed pleiotropy analyses by examining previously published GWAS to identified associated traits (see Additional file 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive MR analysis to examine the causal associations of four herpesvirus infections and AD. Our results found a significant association between mononucleosis and AD, as well as an association between mononucleosis and family history of AD. The result is less susceptible to confounding and reverse causality bias than many previous conventional observational studies [29].

Mendelian randomization rests on three key assumptions [29]. The relevance assumption required that the genetic variants are robustly associated with the exposure of interest. We have selected our IVs from a large GWAS for infections. All SNPs were genome-wide significant (P < 5 × 10−8), which is a very strict threshold. Although the proportion of variance explained by IVs was not very high, the F-statistics were all highly above the threshold of weak instruments of F-statistic < 10 [17]. The other two assumptions are collectively known as independence from pleiotropy. In pleiotropy analyses, we found some SNPs (i.e., rs2596465, rs885950) were associated with “treatment with insulin” from UKB (see Additional file 4). However, recent MR analyses have suggested type-2 diabetes and high plasma glucose are not causally related to the risk of Alzheimer’s disease [30, 31]. According to the existing knowledge, there are no obvious evidences that SNPs in our study influence AD through other pathways, indicating our MR analysis to be valid.

The exposures in our MR analysis were defined by the self-reported history of infection diseases [12] rather than the serological or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) measures of exact pathogens which were often used in observational studies [32]. That was due to the lack of appropriate GWAS. However, researchers have done several surveys to define each infectious disease phenotype and have taken vaccination into account. And their surveys and phenotype scoring logic were showed in the original study [12]. From some point of view, defining infection by clinical diagnosis may have greater clinical significance for AD prevention and may provide a new perspective for exploring the mechanism of the causal effects.

We found evidence that mononucleosis (mainly caused by EBV) [13] was associated with a higher risk of AD. And it was validated using a GWAS dataset of the family history of AD, which enhanced the robustness of the causal relationship. As for EBV, a recent article detected EBV-specific T cell receptors in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with AD; however, their data were still not a directly evidence of a causality [6]. A meta-analysis based on two case–control studies demonstrates that the EBV infection (OR [95% CI] = 1.45 [1.00, 2.08]) is associated with a higher risk of AD [1]. A prospective cohort study also reports that the presence of EBV in the peripheral blood might be a risk factor for AD (OR = 1.843) [32]. Nevertheless, observational results are prone to reverse causation and confounding bias. Taking the advantage of overcoming these limitations adherent in observational studies [29], our MR findings can be used to provide more reliable evidence of causality between EBV and AD.

Although the specific mechanism underlying the association between infection and AD has not been fully understood, studies have proposed several possible mechanisms. Some have suggested that herpesviridae infection could promote the accumulation of amyloid-β plaques in brain [33]. Carbone et al. have suggested that persistent cycles of latency of the EBV might contribute to stress the systemic immune response and induce altered inflammatory processes, resulting in cognitive decline during aging [32]. Also, a recent article has found evidences indicating the effects of adaptive immunity in AD [6]. Our MR finding was from the aspect of mononucleosis other than the latent infection. In light of the fact that over 90% of the world’s adult population is chronically infected with EBV [34], our results from mononucleosis seem to be more practical, which might imply the underlying effects of immune mechanisms and provide contributions to the current literature [6].

There was no clear evidence to suggest an effect of chickenpox or shingles on AD. Although primary analysis showed a significant association between shingles and risk of AD, it was not validated in independent data, and the direction of point estimates in primary analysis and in validation analysis was the opposite. The two infection diseases are caused by VZV; however, chickenpox results from primary infection of VZV, while shingles are caused by the reactivation of the latent VZV within a dorsal root ganglion. Thus, the effect of the two infectious diseases on AD may be different. Although observational studies have found that VZV DNA and sera VZV antibodies showed no positive correlations with AD risk [35,36,37], it is not clear whether the primary infection and reactivation of VZV act differently on AD risk. In particular, recent cohort studies have reported that the use of antiviral agents in herpes zoster patients was associated with lower risks of dementia [38, 39], adding weight to the potential association between VZV infection and dementia. Further investigation is warranted concerning whether VSV reactivation is involved in triggering AD onset or progression.

Our MR results showed no significant association between cold sores, mainly caused by reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), and AD risk. Accumulating evidence suggest HSV-1 alone does not confer an elevated risk of AD [35, 40, 41], but together with the carriage of APOE-ε4 allele increases AD risk [2, 42, 43]. Nevertheless, in an observational study which has determined APOE genotype and other possible confounders previously, they also suggested that both carriage of and reactivated HSV-1 infection increased the risk of developing AD [44]. A likely explanation for those controversial findings is that there could be some unmeasured confounding or other bias [3, 4]. A published MR study has suggested similar results as us that any HSV infection was not related to cognitive function or late-onset AD [8]. However, constrained by the MR approach, the potential link between APOE genotype and HSV-1 cannot be clarified in the present study, which requires further study. On the other hand, although the commonest manifestation of HSV-1 infection are cold-sores, only ~ 40% of people that are seropositive for HSV-1 actually get cold-sores. Therefore, cold sores are only a fairly specific subset of the infectious phenotypes that occur for HSV-1, and the effects of cold sores on AD are not equivalent to that of HSV-1 infection.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this study. First, some exposures have only one or two available SNP in our study, and the phenotypic variance tagged by SNP instruments was low (i.e., mononucleosis = 0.20%). However, it is unlikely to affect the statistical power for our MR analyses. Because the primary results are validated using an independent GWAS, and the sample size of datasets in validation is large enough to give a high power. Second, a general challenge of MR is the persistent possibility of horizontal pleiotropic associations between exposure and outcome. To avoid horizontal pleiotropy, we did pleiotropy analysis and checked phenotypes of each SNP. And based on current knowledge, we found no other associated traits were confirmed to have direct effects on AD. On the other hand, our results are less likely to be affected by pleiotropy and heterogeneity due to the small number of SNPs [7]. Third, participants of infection GWAS are limited to customer base of 23andMe, which may impact the MR results. And the self-reported information may lead to recall bias. Nevertheless, we did not find other appropriate infection GWAS to conduct MR analyses. Importantly, it should be noted that our analysis of infection refers to the infectious diseases caused by specific virus. Whether these present results are tenable in latent infection of those viruses is uncertain because of the different underlying pathologic changes. Moreover, as for mononucleosis, although 90% are caused by EBV, the remaining 10% is caused by other virus such as the human herpesvirus 6, which may limit our inference extended to EBV. Large and precise defined herpesvirus infection GWAS studies are needed to explore the MR application in this field.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found a positive association between mononucleosis and the risk of AD, as well as an association between mononucleosis and family history of AD from MR analysis. Further elucidation of this association could provide insights into the potential biological roles of mononucleosis in AD pathogenesis.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used in this study can be acquired from the original genome-wide association studies that are mentioned in the text. Any other data generated in the analysis process can be requested from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MR:

-

Mendelian randomization

- IV:

-

Instrumental variables

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- VZV:

-

Varicella-zoster virus

- HSV-1:

-

Herpes simplex virus type 1

- IGAP:

-

International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project

- UKB:

-

UK Biobank

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- IVW:

-

Inverse variance weighting

- NOME:

-

NO Measurement Error

- MR-PRESSO:

-

Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier

References

Ou YN, Zhu JX, Hou XH, Shen XN, Xu W, Dong Q, Tan L, Yu JT. Associations of infectious agents with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD. 2020;75:299–09.

Steel AJ, Eslick GD. Herpes viruses increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD. 2015;47:351–64.

Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Kundu D, Bruckdorfer KR, Ebrahim S. Those confounded vitamins: what can we learn from the differences between observational versus randomised trial evidence? Lancet. 2004;363:1724–7.

Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Epidemiology–is it time to call it a day? Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1–11.

Rizzo R. Controversial role of herpesviruses in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008575.

Gate D, Saligrama N, Leventhal O, Yang AC, Unger MS, Middeldorp J, Chen K, Lehallier B, Channappa D, De Los Santos MB, et al. Clonally expanded CD8 T cells patrol the cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2020;577:399–404.

Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA. 2017;318:1925–6.

Kwok MK, Schooling CM. Herpes simplex virus and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;99:101.e11-101.e13.

Lövheim H, Gilthorpe J, Johansson A, Eriksson S, Hallmans G, Elgh F. Herpes simplex infection and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a nested case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:587–92.

Lawlor DA. Commentary: Two-sample Mendelian randomization: opportunities and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:908–15.

Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, Boland A, Vronskaya M, van der Lee SJ, Amlie-Wolf A, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–30.

Tian C, Hromatka BS, Kiefer AK, Eriksson N, Noble SM, Tung JY, Hinds DA. Genome-wide association and HLA region fine-mapping studies identify susceptibility loci for multiple common infections. Nat Commun. 2017;8:599.

Hurt C, Tammaro D. Diagnostic evaluation of mononucleosis-like illnesses. Am J Med. 2007;120(911):e1-8.

Marioni RE, Harris SE, Zhang Q, McRae AF, Hagenaars SP, Hill WD, Davies G, Ritchie CW, Gale CR, Starr JM, et al. GWAS on family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:99.

Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–7.

Myers TA, Chanock SJ, Machiela MJ. LDlinkR: an R package for rapidly calculating linkage disequilibrium statistics in diverse populations. Front Genet. 2020;11:157.

Pierce BL, Ahsan H, Vanderweele TJ. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:740–52.

Burgess S. Sample size and power calculations in Mendelian randomization with a single instrumental variable and a binary outcome. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:922–9.

Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan N, Thompson J. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat Med. 2017;36:1783–802.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14.

Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–98.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25.

Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8.

Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1961–74.

Kamat MA, Blackshaw JA, Young R, Surendran P, Burgess S, Danesh J, Butterworth AS, Staley JR. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4851–3.

Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Kamat MA, Ellis S, Surendran P, Sun BB, Paul DS, Freitag D, Burgess S, Danesh J, et al. PhenoScanner: a database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3207–9.

Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, Laurin C, Burgess S, Bowden J, Langdon R, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. 2018;7:e34408.

Rasooly D, Patel CJ. Conducting a reproducible mendelian randomization analysis using the R analytic statistical environment. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2019;101:e82.

Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:k601.

Benn M, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Frikke-Schmidt R. Impact of glucose on risk of dementia: Mendelian randomisation studies in 115,875 individuals. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1151–61.

Thomassen JQ, Tolstrup JS, Benn M, Frikke-Schmidt R. Type-2 diabetes and risk of dementia: observational and Mendelian randomisation studies in 1 million individuals. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e118.

Carbone I, Lazzarotto T, Ianni M, Porcellini E, Forti P, Masliah E, Gabrielli L, Licastro F. Herpes virus in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to progression of the disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:122–9.

Eimer WA, Vijaya Kumar DK, Navalpur Shanmugam NK, Rodriguez AS, Mitchell T, Washicosky KJ, György B, Breakefield XO, Tanzi RE, Moir RD. Alzheimer’s disease-associated β-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron. 2018;99:56-63.e3.

Sarwari NM, Khoury JD, Hernandez CM. Chronic Epstein Barr virus infection leading to classical Hodgkin lymphoma. BMC hematology. 2016;16:19.

Hemling N, Röyttä M, Rinne J, Pöllänen P, Broberg E, Tapio V, Vahlberg T, Hukkanen V. Herpesviruses in brains in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:267–71.

Ounanian A, Guilbert B, Renversez JC, Seigneurin JM, Avrameas S. Antibodies to viral antigens, xenoantigens, and autoantigens in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 1990;4:367–75.

Lin WR, Casas I, Wilcock GK, Itzhaki RF. Neurotropic viruses and Alzheimer’s disease: a search for varicella zoster virus DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:586–9.

Bae S, Yun SC, Kim MC, Yoon W, Lim JS, Lee SO, et al. Association of herpes zoster with dementia and effect of antiviral therapy on dementia: a population-based cohort study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:987–97.

Chen VC, Wu SI, Huang KY, Yang YH, Kuo TY, Liang HY, et al. Herpes zoster and dementia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:16m11312.

Linard M, Letenneur L, Garrigue I, Doize A, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Interaction between APOE4 and herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:200–8.

Itzhaki RF, Lin WR, Shang D, Wilcock GK, Faragher B, Jamieson GA. Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1997;349:241–4.

Lövheim H, Norman T, Weidung B, Olsson J, Josefsson M, Adolfsson R, Nyberg L, Elgh F. Herpes simplex virus, APOEɛ4, and cognitive decline in old age: results from the Betula Cohort Study. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD. 2019;67:211–20.

Lopatko Lindman K, Weidung B, Olsson J, Josefsson M, Kok E, Johansson A, Eriksson S, Hallmans G, Elgh F, Lövheim H. A genetic signature including apolipoprotein Eε4 potentiates the risk of herpes simplex-associated Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement (New York, N Y). 2019;5:697–704.

Lövheim H, Gilthorpe J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, Elgh F. Reactivated herpes simplex infection increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:593–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the generous sharing of GWAS summary statistics. We thank the participants, researchers, and staff associated with the many other studies from which we used data for this report. We thank the UK Biobank for providing summary statistics for these analyses. We also thank the IGAP for providing summary results data for these analyses. The investigators within IGAP contributed to the design and implementation of IGAP and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. IGAP was made possible by the generous participation of the control subjects, the patients, and their families. The i–Select chips were funded by the French National Foundation on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. EADI was supported by the LABEX DISTALZ grant, Inserm, Institut Pasteur de Lille, Université de Lille 2 and the Lille University Hospital. GERAD was supported by the Medical Research Council (grant no 503480), Alzheimer’s Research UK (grant no 503176), the Wellcome Trust (grant no 082604/2/07/Z), and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Competence Network Dementia (CND) grant no 01GI0102, 01GI0711, 01GI0420. CHARGE was partly supported by the NIH/NIA grant R01 AG033193 and the NIA AG081220 and AGES contract N01–AG–12100, the NHLBI grant R01 HL105756, the Icelandic Heart Association, and the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University. ADGC was supported by the NIH/NIA grants: U01 AG032984, U24 AG021886, U01 AG016976, and the Alzheimer’s Association grant ADGC–10–196728.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91849126), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1314702), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No.2018SHZDZX01) and ZHANGJIANG LAB, Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute, and the State Key Laboratory of Neurobiology and Frontiers Center for Brain Science of Ministry of Education, Fudan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jin-Tai Yu had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Jin-Tai Yu, Qiang Dong, Lan Tan. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Shu-Yi Huang, Yu-Xiang Yang, Kevin Kuo, Hong-Qi Li, Xue-Ning Shen, Shi-Dong Chen, Mei Cui. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Shu-Yi Huang, Yu-Xiang Yang. Obtained funding: Jin-Tai Yu. Administrative, technical, or material support: Jin-Tai Yu, Qiang Dong, Lan Tan, Yu-Xiang Yang, Mei Cui. Supervision: Jin-Tai Yu. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All data sources used in this MR study received approval from an ethics standards committee on human experimentation and obtained informed consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Mendelian randomization analyses of the association between herpesvirus infections and Alzheimer's disease.

Additional file 2

. Sensitivity analysis, heterogeneity analysis and pleiotropy analysis of the association between shingles and Alzheimer's disease.

Additional file 3

. Summary statistics for the genetic variants used to assess the effect of herpesvirus infections on Alzheimer's disease in the present Mendelian randomization study.

Additional file 4

. Single SNP analysis of the association between mononucleosis, cold sores, chickenpox, shingles and Alzheimer's disease.

Additional file 5.

Evidence of association (p<5×10-8) of significant SNP with other traits.

Additional file 6

. Leave-one-out plots, forest plots, and scatter plots.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, SY., Yang, YX., Kuo, K. et al. Herpesvirus infections and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Alz Res Therapy 13, 158 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00905-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00905-5