Abstract

Background

Understanding the changes that occur in the transitional stage between absent and overt amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology within the Alzheimer’s continuum is crucial to develop therapeutic and preventive strategies. The objective of this study is to test whether cognitively unimpaired individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology have a distinct CSF, structural, and functional neuroimaging biomarker profile.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of 318 middle-aged, cognitively unimpaired individuals from the ALFA+ cohort. We measured CSF Aβ42/40, phosphorylated tau (p-tau), total tau (t-tau), neurofilament light (NfL), neurogranin, sTREM2, YKL40, GFAP, IL6, S100B, and α-synuclein. Participants also underwent cognitive assessments, APOE genotyping, structural MRI, [18F]-FDG, and [18F]-flutemetamol PET.

To ensure the robustness of our results, we used three definitions of low burden of Aβ pathology: (1) positive CSF Aβ42/40 and < 30 Centiloids in Aβ PET, (2) positive CSF Aβ42/40 and negative Aβ PET visual read, and (3) 20–40 Centiloid range in Aβ PET. We tested CSF and neuroimaging biomarker differences between the low burden group and the corresponding Aβ-negative group, adjusted by age and sex.

Results

The prevalence and demographic characteristics of the low burden group differed between the three definitions. CSF p-tau and t-tau were increased in the low burden group compared to the Aβ-negative in all definitions. CSF neurogranin was increased in the low burden group definitions 1 and 3, while CSF NfL was only increased in the low burden group definition 1. None of the defined low burden groups showed signs of atrophy or glucose hypometabolism. Instead, we found slight increases in cortical thickness and metabolism in definition 2.

Conclusions

There are biologically meaningful Aβ-downstream effects in individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology, while structural and functional changes are still subtle or absent. These findings support considering individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology for clinical trials.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has an initial preclinical stage characterized by brain deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau, without clinical manifestations [1,2,3,4,5]. Moreover, other pathophysiological processes occur in this preclinical stage, including microglial activation, synaptic dysfunction, neuronal injury, and vascular dysfunction [6,7,8]. All these processes can occur years or even decades before the onset of the first symptoms [5, 9, 10]. Researchers, clinicians, and stakeholders in the AD field have learnt that the chances to succeed are higher if prevention and treatment interventions targeting these processes are applied as early as possible.

Aβ pathology can be detected with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and Aβ positron emission tomography (PET). The Aβ cut-offs typically used to define Aβ-positivity (Aβ+) or Aβ-negativity (Aβ-) are usually derived from symptomatic AD patients and are extremely useful for clinical diagnosis at these stages. However, whilst the Aβ biomarker values in symptomatic AD show a bimodal distribution, in the preclinical stage, there is a progressive accumulation of Aβ. Therefore, the thresholds for diagnostic classification may not be optimal to detect subtle Aβ pathology in Aβ- individuals [11].

Growing evidence indicates that these Aβ subtle changes are meaningful [12]: Longitudinal analyses showed that subthreshold Aβ PET levels predict cognitive decline and tau deposition [13, 14]. Interestingly, the strongest association between subthreshold Aβ and cognition is found to occur in the middle age group [15]. Moreover, the rate of change of Aβ deposition peaks with an intermediate Aβ load, suggesting the existence of a critical time window for Aβ-lowering interventions [16,17,18,19].

Understanding this transitional stage from completely absent to overt amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology is key for clinical trials focused at this early stage. Our aim was to determine whether individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology have a distinct CSF and neuroimaging biomarker profile that distinguish them from those who are clearly Aβ-. We hypothesized that subtle Aβ pathology (even below the usual thresholds for PET Aβ positivity) is already associated with Aβ-downstream pathophysiological changes, and/or cerebral structural and functional changes. In a cross-sectional design, we studied cognitively unimpaired individuals of the ALFA+ cohort. In order to ensure robustness, we applied three different definitions of low burden of Aβ pathology, in two of them combining both CSF and PET Aβ.

Methods

Participants

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in the ALFA+ cohort, a nested longitudinal study of the ALFA (for ALzheimer’s and FAmilies) study [20]. The ALFA study aims at characterizing preclinical Alzheimer’s and comprises 2743 cognitively unimpaired individuals, aged between 45 and 75 years old and enriched for family history of AD and APOE-ε4 status.

Among the 381 ALFA+ participants with CSF biomarkers available, we initially excluded those categorized as Aβ-negative (CSF Aβ42/40 ratio > 0.071) but tau-positive (CSF p-tau > 24 pg/ml) (n =12) to focus our study on the Alzheimer’s continuum. From those, we included participants that also had Aβ PET and FDG PET available (n = 318). Structural MRI with automatic segmentation was available in a total of 303 participants.

CSF collection, processing, and storage: CSF biomarker measurements

CSF samples were obtained by lumbar puncture following standard procedures [21, 22]. Total tau and phosphorylated tau measurements were performed using the electrochemiluminescence immunoassays Elecsys® Total-tau CSF and Phospho-Tau(181P) CSF on a fully automated cobas e 601 instrument (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd.) [23]. Amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42) [24], amyloid-β 40 (Aβ40), neurofilament light (NfL), neurogranin, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (sTREM2), chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL40), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and α-synuclein were measured with the prototype NeuroToolKit (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd.) on a cobas e 411 instrument. Interleukin 6 (IL6) and calcium-binding protein B (S100B) were measured with the prototype NeuroToolKit (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd.) on a cobas e 601 instrument. All the measurements were conducted at the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden.

Neuroimaging data acquisition

Participants underwent [18F]-FDG and [18F]-flutemetamol PET scans following a cranial computed tomography (CT) scan for attenuation correction on a Siemens Biograph64 mCT camera. For acquiring [18F]-flutemetamol PET scans, participants received an intravenous bolus dose of 185 MBq (range 104.25–218.3 MBq, mean ± SD: 191.75 ± 14.04) and PET data was acquired after a 90-min post-injection (mean ± SD: 90.15 ± 7.36 min). [18F]-FDG PET scans were acquired 45 min (mean ± SD: 45.69±4.67) post-injection of 185 MBq (range 181.3–222 MBq, mean ± SD: 200.83 ± 12.83 MBq). All PET data were acquired for 20 min, using 4 frames of 5 min. PET images were reconstructed in 4 frames × 5 min using 3D ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM) algorithm by incorporating time of flight (TOF) and point spread function (PSF) modeling.

MRI scans were obtained with a 3T scanner (Ingenia CX, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The MRI protocol was identical for all participants and included a high-resolution 3D T1-weighted Turbo Field Echo (TFE) sequence (voxel size 0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 mm, TR/TE: 9.90/4.6 ms, flip angle = 8°).

Visual assessment

Qualitative assessments were done for T1-weighted MRI and [18F]-flutemetamol PET images. A trained radiologist validated the image quality of MRI scans as well as incidental findings. Aβ PET images were visually rated by a nuclear medicine physician as Aβ+ or Aβ- using standard clinical criteria as specified in the Summary of Product Characteristics of the tracer [25].

[18F]-flutemetamol PET quantification

[18F]-flutemetamol PET processing was performed following a validated Centiloid pipeline [26] using SPM12 [27]. Centiloid values (CL) were calculated from the mean values of the standard CL target region (http://www.gaain.org/centiloid-project) using the transformation previously calibrated [27].

[18F]-FDG PET quantification

Quantification of [18F]-FDG PET was done by calculating the standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) within the region of interest (ROI). All preprocessing steps were performed using SPM12.

SUVr values were calculated within a ROI composite, referred to as Meta-ROI. This composite was created by identifying regions cited frequently in [18F]-FDG PET studies of AD and MCI patients by Landau et al. [28]. ROI composite consists of five sub-regions including right and left angular gyri, middle/inferior temporal gyrus, and bilateral posterior cingulate gyrus. Meta-ROI SUVr of each [18F]-FDG PET image was calculated by averaging the SUVr over all the voxels involved in the Meta-ROI composite.

Structural MRI quantification

T1-weighted images were automatically segmented and cortical thickness was measured in the regions from the Desikan-Killiany cortical atlas using Freesurfer version 6.0 [29]. Segmentation results were visually quality controlled by an expert. The cortical AD signature was then estimated for each subject based on the thickness of the following areas: entorhinal, inferior temporal, middle temporal, and fusiform. The signature was calculated as the mean thickness across these regions weighted by their surface area, as previously proposed [18, 30]. Additionally, we selected a set of individual regions to be included in the analysis, namely the banks of the superior temporal sulcus (bankssts), precuneus, and hippocampus, all sensitive to AD pathology [18, 31, 32].

Low burden of Aβ pathology definitions

Aβ pathology was assessed using both CSF Aβ and Aβ PET. For CSF, Aβ-positivity (Aβ+) was defined as CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 < 0.071. This cutoff was previously established in the ALFA+ cohort using a Gaussian Mixture Model approach. The cutoff was defined as the mean minus 2 standard deviations (SD) of the non-pathologic Gaussian distribution of the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio [22]. Therefore, it corresponds to a degree of abnormality rather than a diagnostic cutoff. Aβ PET was assessed either by the CL scale or visual read. For the CL scale, we used the cutoff of 30 CL because it falls within the range of agreement with the visual read method in clinical populations (24–35 CL) and therefore marks established Aβ pathology [27, 33,34,35,36]. Alternatively, Aβ PET visual read was categorized as Aβ+ or Aβ- by a trained nuclear medicine physician and is the outcome used for clinical purposes and, typically, to recruit participants for anti-Aβ drug trials. Finally, we also used the range of 20–40 CL criteria because it is currently being used in preclinical AD clinical studies [18, 37] and can be informative for them.

We defined the group of participants with a low burden of Aβ pathology, referred to as the “low burden” group, using a combination of the aforementioned biomarkers cutoffs (Table 1):

-

Definition 1: the low burden group was defined as those participants having a positive CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and CL values below 30 in Aβ PET. This group was compared with the Aβ- group (negative CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and CL < 30).

-

Definition 2: the low burden group was defined as positive CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and negative Aβ PET visual read, and was compared with the Aβ- group (negative CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and negative Aβ PET visual read).

-

Definition 3: the low burden group was defined as CL values ranging from 20 to 40 in Aβ PET, and was compared with the Aβ- group (CL < 20).

Statistical analysis

CSF biomarkers and neuroimaging variables extreme values, defined by 3 times the interquartile range below the first quartile or above the third quartile, were excluded. The following number of extreme values were identified and excluded: 4 for p-tau, 2 for t-tau, 3 for NfL, 1 for neurogranin, 1 for GFAP, 9 for IL6, 1 for S100B, and 12 for α-synuclein. In the main text, we show all the analyses excluding these extreme values. In the Additional file (Table S2), we show the same analyses including them.

The normality of each biomarker distribution was assessed using visual inspection of the histogram and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. None of the biomarkers, except Aβ42/40 and sTREM2, followed a normal distribution and they were thus log10-transformed.

We performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences in age, years of education, and MMSE performance between the Aβ-, low burden and Aβ+ groups, and a Pearson’s chi-squared test to test differences in the distribution of sex and APOE-ε4 genotypes. APOE genotype was binarized as APOE-ε4 carriers or non-carriers.

CSF biomarker levels and neuroimaging variables were compared between groups using a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for the effect of age and sex. Hippocampal volume analyses were also adjusted by the estimated total intracranial volume (eTIV). All significant comparisons were followed by Dunnett-corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons, with the Aβ- group as the reference group.

All tests were 2-tailed, with a significance level of α = 0.05. We applied a false discovery rate (FDR) multiple comparison correction following the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure [38].

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS IBM, version 20.0, statistical software and the open-source statistical software R. Figures were built using R.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The ALFA+ study (ALFA-FPM-0311) was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee “Parc de Salut Mar”, Barcelona, and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02485730). All participating subjects signed the study’s informed consent form that had also been approved by the Independent Ethics Committee “Parc de Salut Mar”, Barcelona.

Data availability statement

Due to participant’s privacy, individual-level data cannot be made publicly available. Researchers who wish to use data from the ALFA study must obtain approval from the ALFA study Management Team.

Results

Participants’ characteristics and low burden groups

We included 318 cognitively unimpaired, middle-aged (50–74 years old) participants from the ALFA+ cohort. We first compared the prevalence of the low burden group between the three definitions used, and it differed considerably: 88 (27.7%), 72 (23.0%), and 18 (5.66%) participants fulfilled low burden criteria for definitions 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Table 2 and Table S1 in Additional file).

Participants with a low burden of Aβ pathology were significantly older than the Aβ- group participants only using definition 3, which uses Aβ PET but not CSF Aβ42/20 as a criterion (P = 0.007) (Table 2). In contrast, definitions 1 and 2, that include both Aβ PET and CSF Aβ42/20 as criteria, the low burden group mean age did not differ from that of the Aβ- group. For all definitions, participants in the Aβ+ groups were significantly older than those in the Aβ- group (P < 0.0001). In definitions 1 and 2, Aβ+ group participants were also older than those in the low burden group (P < 0.0001).

In definitions 1 and 2, the low burden group showed a higher prevalence of APOE-ε4 carriers than the Aβ- group (Table 2). In definition 3, there was a significant difference in the prevalence of APOE-ε4 among groups, but this did not survive the post hoc multiple comparisons (Table 2). Although definition 3 was only defined by Aβ PET CL, all the individuals in its low burden group (n = 18) had also abnormal CSF Aβ42/40 levels. No significant differences were found in the distribution of sex, education years, or cognitive performance among groups in any of the three definitions studied.

CSF biomarker changes in individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology

We next assessed whether participants with a low burden of Aβ pathology presented significant differences in AD CSF biomarkers’ levels, which would suggest that other AD-related pathophysiological processes different from Aβ pathology are already activated in this transitional stage.

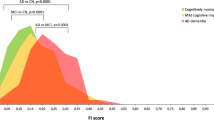

We observed that CSF p-tau and t-tau were significantly increased in the low burden group compared to the Aβ- one in the three definitions (Table 3, Fig. 1). Moreover, CSF neurogranin was also significantly higher in the low burden group than in the Aβ- group in definitions 1 and 3 (Table 3, Fig. 1). Importantly, in definition 1, CSF NfL was also significantly increased in the low burden group, whilst a trend in the same direction is observed in definition 3 (P = 0.070). In the analyses including the extreme values (Table S2 in Additional file), the significant increase in CSF NfL in the low burden group in definition 1 was lost (P = 0.051).

Comparison of CSF p-tau, t-tau, NfL, and neurogranin between Aβ groups. The boxplots depict the median (horizontal bar), interquartile range (IQR hinges), and 1.5 × IQR (whiskers). Group differences were assessed by a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted by age and sex, followed by Dunnett-corrected pairwise post hoc comparisons. We show the percentage of increase in the mean of each biomarker in the low burden group compared to the Aβ- group. The percentage is shown in bold if the difference is statistically significant. “Low burden” refers to “low burden of Aβ pathology”. NS, not significant. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001; ****P <0.0001

In definition 2, CSF neurogranin and NfL also showed a trend to increased values in the low burden group, but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.081 and P = 0.080 for CSF neurogranin and NfL, respectively) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Importantly, the magnitude of the changes in CSF biomarkers between the low burden and the Aβ- group differed considerably between definitions. In definition 3, the magnitude of the differences was always higher than those of definitions 1 and 2 (Fig. 1). In the case of CSF p-tau, the magnitude of change ranged from 17.4% (definition 2) to 34.2% (definition 3). For CSF t-tau, it ranged from 13.1% (definition 2) to 30.6% (definition 3). Group differences in CSF neurogranin ranged from 10.4% (definition 2) to 27.3% (definition 3), and those of CSF NfL from 9.15% (definition 2) to 27.3% (definition 3) (Fig. 1). This suggests that the low burden groups in definitions 1 and 2 capture a population with lower Aβ accumulation (as shown by their mean CL levels), which may suggest an earlier disease stage in the Alzheimer’s continuum than that in definition 3.

As expected, there was an increase in several CSF biomarkers in the Aβ+ group compared to the Aβ- one. CSF p-tau, t-tau, NfL, neurogranin, YKL40, and GFAP were increased in the Aβ+ group compared to the Aβ- group in the three definitions (Table 3; Fig. 1; Fig. S1 in Additional file).

Structural brain changes associated with a low burden of Aβ pathology

We assessed whether a low burden of Aβ pathology was also associated with structural brain changes. Unlike the CSF biomarker results, there were no differences in the AD signature MRI Meta-ROI composite of the low burden and Aβ+ groups compared to the Aβ- groups in any of the three definitions. However, when we looked at the individual regions of interest that compose the AD signature, the low burden group in definition 2 showed a greater cortical thickness in the right fusiform gyrus compared to the Aβ- group (P = 0.049). In definition 2, there was also a trend to group differences in the middle temporal region, but it did not survive post hoc multiple comparisons (Table S3 in Additional file).

Among the other individual regions of interest analyzed, we found an increase in cortical thickness of the left bankssts in individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology in definition 2 compared to Aβ- ones (P = 0.028). A trend to the same result was observed in definition 1 (group main effect P = 0.068). Noteworthy, these differences were not observed in the Aβ+ group (Table S3 in Additional file).

Brain metabolism changes associated with a low burden of Aβ pathology

We next explored whether a low burden of Aβ pathology was associated with changes in brain metabolism as measured by FDG PET. Analysis of the AD signature FDG PET Meta-ROI composite showed no significant changes in the low burden group compared to the Aβ- in any of the three definitions. In contrast, Aβ+ individuals in definition 2 had a higher metabolism compared to Aβ- ones (P = 0.029) (Table S4 in Additional file).

We next analyzed the individual regions included in the Meta-ROI composite. In definition 1, there was a trend to a higher metabolism in the left angular gyrus in the low burden group compared to the Aβ- one (P = 0.066). In definition 2, this increase in metabolism in the angular gyrus was bilateral and significant in the Aβ+ group but not in the low burden group (Table S4 in Additional file). No significant group differences were found in any region studied in definition 3.

All significant results in the MRI and FDG PET analyses did not survive FDR multiple comparison correction (Table S3 and S4 in Additional file) and should therefore be interpreted as exploratory.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology, and before overt Aβ deposition is present, already show typical AD pathophysiological changes. Specifically, we found that the main AD CSF biomarkers, reflecting tau, synaptic, and neurodegenerative changes, are already altered at this stage, whilst structural and functional brain changes are still minimal or absent.

The long preclinical stage of the Alzheimer’s continuum includes a transition from the complete absence of pathology, followed by incipient subtle Aβ pathology and eventual overt Aβ and tau pathology [5]. In our study, we examined those individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology, that is, individuals below the Aβ PET positivity typical thresholds but with some signs of subtle Aβ changes (shown by either CSF or PET Aβ biomarkers), probably reflecting a stage when Aβ pathology is emerging. The choice of the term “low burden of Aβ pathology” to define this stage was not arbitrary. This term objectively describes the biomarker findings, stresses the transitional nature of these initial Aβ-related changes, and it does not have temporal connotations (as the terms “emerging” or “incipient” pathology may have). Herein, we defined this low burden stage in three different ways. Two of them (definition 1 and definition 2) were based on the mismatch between CSF and PET Aβ-positivity, which reflects an early stage of Aβ dysregulation when CSF biomarkers have started to change but Aβ PET is still not positive [39, 40]. For Aβ PET classification, we used two different criteria: the CL scale, usually used for research purposes [26], and the visual read, usually used in the clinical setting. Definition 3 was merely based on a CL values window, which includes participants who are not above the threshold for Aβ positivity but show intermediate level of Aβ pathology in Aβ PET. By using different definitions of the low burden of Aβ pathology, we intended to confirm the consistency of our results and, at the same time, to assess definitions that may be or are already being used in studies at this early stage [18, 37]. Noticeably, the prevalence and the demographic characteristics of the low burden group are considerably different depending on the definition used, an issue that should be taken into consideration when designing studies at this stage.

Our most consistent finding was that some AD CSF biomarkers change as early in the continuum as there is evidence of a low Aβ pathological burden. Specifically, we observed an increase in CSF biomarkers reflecting tau pathology (p-tau), synaptic dysfunction (neurogranin), and neurodegeneration (t-tau and NfL). Nevertheless, there are some differences depending on the definition used. The low burden group as defined by definition 1 (i.e., CSF Aβ positive and CL < 30) shows significant changes in CSF p-tau, t-tau, neurogranin, and NfL. This is followed by definition 3 (i.e. CL 20–40), with significant increases in CSF p-tau, t-tau, neurogranin, and a tendency to increased CSF NfL. To note, the CSF biomarkers changes in definition 3 were those with the highest magnitude. Finally, the low Aβ pathology burden group in definition 2 (i.e., CSF Aβ positive and visual read negative) had increased CSF p-tau and t-tau but only a tendency to increased CSF neurogranin and NfL. In respect to this, the definition of visual read positivity in our sample is reached most probably at an equivalent CL value considerably lower than 30, within the range of 12–20 CL [41] [Lyduine Collij; Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2020]. Therefore, definition 2 low Aβ pathology burden group would encompass the earliest of these three definitions of Aβ pathology, when only tau-related CSF biomarkers start to increase. Overall, these results are consistent with those showing that levels of Aβ pathology below the generally used Aβ PET thresholds can be biologically and clinically meaningful and predict subsequent tau pathology or cognitive decline [13, 14].

We also assessed possible structural and functional changes in individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology. We investigated the structural MRI and FDG PET AD signatures as well as other areas of interest known to change early in AD [18, 31, 32]. The results were not as clear as those of the CSF biomarkers. We did not observe a significant decrease in cortical thickness or brain metabolism in any of the regions of interest in neither the low burden nor the Aβ+ groups. This probably reflects the early stage of our population in terms of the absence of Aβ-downstream structural and functional consequences (e.g., reduction of brain volume and decreased metabolism), which would be expected in later stages of the continuum. On the contrary, our results suggest a subtle trend to increased cortical thickness in the group of participants with a low burden of Aβ pathology (definition 2) but not in the Aβ+ group, especially in the bankssts and the right fusiform gyrus. This result is in line with previous findings that showed a nonlinear relationship between Aβ and cortical thickness, so that there is thickening in the bankssts region in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with intermediate CSF Aβ values [32]. Similarly, we observed a slight trend to an increased glucose metabolism, especially in the angular gyrus, associated to Aβ pathology.

The main reason underlying the differences in CSF and neuroimaging biomarker changes between the different low burden group definitions is that they probably capture different stages in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Definitions including CSF biomarkers (definitions 1 and 2) probably reflect earlier stages, while an approach solely defined by Aβ PET (definition 3) may reflect a later stage. This explains why definition 3 has the highest magnitude of changes in CSF biomarkers. Of note, all individuals of the definition 3 low burden group have also abnormal CSF Aβ42/40. In contrast, definition 2 low burden group may capture an earlier stage, as shown by its higher CSF Aβ42/40 ratio and lower CL values, and that could explain why there are mild increases in cortical thickness. This is an important consideration when designing an interventional study. If the study includes participants in the very early stage of the continuum (as apparently occurs in definition 2 of our study), non-monotonic changes in neuroimaging biomarkers should be considered. We should however acknowledge that there are other factors that may underlie the different results that we found between definitions as well as their different prevalence. CSF-based definitions may be also influenced by decreased CSF production or clearance with age or the fact that there are lower/higher Aβ producer individuals [42,43,44]. Still, the use of CSF Aβ42/40 ratio, instead of CSF Aβ42, accounts, at least partially, for these factors [45]. We also should keep in mind that this low burden group is a transitory category, and its prevalence may be also affected by age and prevalence of APOE-ε4 [46]. Remarkably, our cohort includes middle-aged healthy individuals, when Aβ pathology most likely starts and with a low prevalence of other co-morbidities (e.g., vascular risk factors, neuronal injury due to other causes) that may affect the biomarker results. Also, the prevalence of APOE-ε4 carriers was similar between the low burden groups of the three definitions.

Strenghts and limitations

Our study is not free of limitations. It is a cross-sectional study and longitudinal studies assessing the evolution of Aβ pathology and Aβ-downstream pathological cascade are crucial. We presume that the low burden group represents an incipient stage of the disease and many of the individuals belonging to this group will most likely progress in the continuum. This is probably a heterogeneous group and it needs to be investigated what other factors may influence the eventual progression of these individuals to symptomatic stages. Moreover, we acknowledge that there are differences in the number of individuals in each low burden definition, which precludes statistical comparisons between them. Finally, none of the neuroimaging analyses survived FDR multiple comparisons correction and should therefore be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, our study has several strengths. First, the ALFA+ cohort encompasses middle age cognitively unimpaired individuals at higher risk of AD and therefore is an optimal population to study pathophysiological pathways emerging in the earliest stage of the Alzheimer’s continuum. Second, we have defined the low burden of Aβ pathology in three different ways, consistently observing similar results in the three of them. Finally, this is a multimodal study including a wide range of CSF biomarkers, as well as brain structure and metabolism markers.

Conclusions

We show that there are biologically meaningful effects in individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology, when structural and functional changes are yet either very subtle or absent. It still remains unanswered whether there is a therapeutic window in this very early stage (when Aβ probably starts to emerge and Aβ-related tau pathology and synaptic dysfunction progressively arise), and a later stage, still within preclinical Alzheimer, when neurodegeneration and downstream consequences in structural and functional neuroimaging measures occur. Yet, our findings suggest that there might be a window of opportunity for AD prevention that starts even before Aβ PET is positive using the typical thresholds. Following the idea that acting very early in AD is a priority, our results support the notion that individuals with even subtle Aβ changes should also be considered for inclusion in early prevention or intervention trials.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-β

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CL:

-

Centiloid

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- p-tau:

-

Phosphorylated tau

- t-tau:

-

Total tau

- NfL:

-

Neurofilament light

- sTREM2:

-

Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2)

- S100B:

-

S100 calcium-binding protein B

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- IL6:

-

Interleukin 6

- VR:

-

Visual read

- YKL40:

-

Chitinase-3-like protein 1

References

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A / T / N : An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016:1–10.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002.

Milà-Alomà M, Suárez-Calvet M, Molinuevo JL. Latest advances in cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:175628641988881.

Bos I, Vos S, Verhey F, Scheltens P, Teunissen C, Engelborghs S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration, synaptic integrity, and astroglial activation across the clinical Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(5):644–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.004.

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Öhrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3.

Fagan AM, Xiong C, Jasielec MS, Bateman RJ, Goate AM, Benzinger TLS, et al. Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:226ra30.

Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1202753.

Villeneuve S, Rabinovici GD, Cohn-Sheehy BI, Madison C, Ayakta N, Ghosh PM, et al. Existing Pittsburgh Compound-B positron emission tomography thresholds are too high: statistical and pathological evaluation. Brain. 2015;138(7):2020–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv112.

Bischof GN, Jacobs HIL. Subthreshold amyloid and its biological and clinical meaning. Neurology. 2019;93(2):72–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007747.

Leal SL, Lockhart SN, Maass A, Bell RK, Jagust WJ. Subthreshold amyloid predicts tau deposition in aging. J Neurosci. 2018;38(19):4482–9. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0485-18.2018.

Landau SM, Horng A, Jagust WJ. Memory decline accompanies subthreshold amyloid accumulation. Neurology. 2018;90(17):e1452–60. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005354.

Bischof GN, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Park DC. Amyloid deposition in younger adults is linked to episodic memory performance. Neurology. 2016;87:2562–6.

Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):357–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9.

Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Lesnick TG, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, et al. Brain β-amyloid load approaches a plateau. Neurology. 2013;80(10):890–6. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182840bbe.

Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:205–16.

Sutphen CL, McCue L, Herries EM, Xiong C, Ladenson JH, Holtzman DM, et al. Longitudinal decreases in multiple cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neuronal injury in symptomatic late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(7):869–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.012.

Molinuevo JL, Gramunt N, Gispert JD, Fauria K, Esteller M, Minguillon C, et al. The ALFA project: a research platform to identify early pathophysiological features of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;2:82–92.

Teunissen CE, Tumani H, Engelborghs S, Mollenhauer B. Biobanking of CSF: international standardization to optimize biomarker development. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:288–92.

Milà-Alomà M, Salvadó G, Gispert JD, Vilor-Tejedor N, Grau-Rivera O, Sala-Vila A, et al. Amyloid beta, tau, synaptic, neurodegeneration, and glial biomarkers in the preclinical stage of the Alzheimer’s continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(10):1358–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12131.

Lifke V, Kollmorgen G, Manuilova E, Oelschlaegel T, Hillringhaus L, Widmann M, et al. Elecsys® Total-Tau and Phospho-Tau (181P) CSF assays: analytical performance of the novel, fully automated immunoassays for quantification of tau proteins in human cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Biochem. 2019;72:30–8.

Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, Ostlund RE, Militello M, Andreasson U, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of β-amyloid (1-42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:517–26.

Agency EM. ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vizamyl-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, Benzinger TL, Devous MD, Jagust WJ, et al. The Centiloid project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1–15.e4.

Salvadó G, Molinuevo JL, Brugulat-Serrat A, Falcon C, Grau-Rivera O, Suárez-Calvet M, et al. Centiloid cut-off values for optimal agreement between PET and CSF core AD biomarkers. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11:27.

Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, et al. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(7):1207–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.002.

Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012:774–81.

Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Knopman DS, Lowe V, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence of cerebral β-amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired individuals aged 50–95 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):435–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30077-7.

Landau SM, Lu M, Joshi AD, Pontecorvo M, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Comparing positron emission tomography imaging and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of β-amyloid. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(6):826–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.23908.

Fortea J, Sala-Llonch R, Bartrés-Faz D, Lladó A, Solé-Padullés C, Bosch B, et al. Cognitively preserved subjects with transitional cerebrospinal fluid ß-amyloid 1-42 values have thicker cortex in Alzheimer’s disease vulnerable areas. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:183–90.

La Joie R, Ayakta N, Seeley WW, Borys E, Boxer AL, DeCarli C, et al. Multisite study of the relationships between antemortem [11 C]PIB-PET Centiloid values and postmortem measures of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:205–16.

Amadoru S, Doré V, McLean CA, Hinton F, Shepherd CE, Halliday GM, et al. Comparison of amyloid PET measured in Centiloid units with neuropathological findings in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:22.

Leuzy A, Chiotis K, Hasselbalch SG, Rinne JO, de Mendonça A, Otto M, et al. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β in a multicentre European memory clinic study. Brain. 2016;139(9):2540–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aww160.

Rowe CC, Doré V, Jones G, Baxendale D, Mulligan RS, Bullich S, et al. 18F-Florbetaben PET beta-amyloid binding expressed in Centiloids. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:2053–9.

AHEAD 3-45 study: a study to evaluate efficacy and safety of treatment with BAN2401 in participants with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and elevated amyloid and also in participants with early preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and intermediate amyloid - Fu [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 15]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04468659?term=NCT04468659&draw=2&rank=1

Benjamini, Yoav ; Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300.

Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Hansson O. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis detects cerebral amyloid-β accumulation earlier than positron emission tomography. Brain. 2016;139(4):1226–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aww015.

Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, Landau S, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, et al. Independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138(3):772–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu367.

Milà-Alomà M, Salvadó G, Shekari M, Grau-Rivera O, Sala-Vila A, Sánchez-Benavides G, et al. Comparative analysis of different definitions of Amyloid-B positivity to detect early downstream pathophysiological alterations in preclinical Alzheimer. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021;8(1):68–77. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2020.51.

Chen CPC, Chen RL, Preston JE. The influence of ageing in the cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of proteins that are derived from the choroid plexus, brain, and plasma. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(4):323–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.01.008.

Masseguin C, LePanse S, Corman B, Verbavatz JM, Gabrion J. Aging affects choroidal proteins involved in CSF production in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:917–27.

Chiu C, Miller MC, Caralopoulos IN, Worden MS, Brinker T, Gordon ZN, et al. Temporal course of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and amyloid accumulation in the aging rat brain from three to thirty months. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2012;9:3.

Van Harten AC, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Mielke MM, Kremers WK, Eichenlaub U, et al. CSF biomarkers in Olmsted County: evidence of 2 subclasses and associations with demographics. Neurology. 2020;95(3):E256–67. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009874.

Toledo JB, Zetterberg H, Van Harten AC, Glodzik L, Martinez-Lage P, Bocchio-Chiavetto L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker in cognitively normal subjects. Brain. 2015;138:2701–15.

Acknowledgements

This publication is part of the ALFA study (ALzheimer and FAmilies). The authors would like to express their most sincere gratitude to the ALFA project participants, without whom this research would have not been possible. The collaborators of the ALFA study are Annabella Beteta, Raffaele Cacciaglia, Alba Cañas, Carme Deulofeu, Irene Cumplido, Ruth Dominguez, Maria Emilio, Sherezade Fuentes, Laura Hernandez, Gema Huesa, Jordi Huguet, Paula Marne, Tania Menchón, Albina Polo, Sandra Pradas, Anna Soteras, and Marc Vilanova. The authors would like to thank GE Healthcare for kindly providing [18F]flutemetamol doses of ALFA+ participants. The authors thank Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. for providing the kits to measure CSF biomarkers. ELECSYS, COBAS, and COBAS E are the trademarks of F-Hoffman La-Roche, Ltd. The Elecsys β-Amyloid (1-42) CSF immunoassay used is a robust prototype assay for research use and is not a commercially available IVD assay. The measuring range of the assay is 200 (lower technical limit)–1700 pg/ml (upper technical limit). The performance of the assay beyond the upper technical limit has not been formally established. Therefore, the use of values above the upper technical limit, which are provided based on an extrapolation of the calibration curve, is restricted to exploratory research purposes and is excluded for clinical decision making.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation (LCF/PR/GN17/10300004) and the Alzheimer’s Association and an international anonymous charity foundation through the TriBEKa Imaging Platform project (TriBEKa-17-519007). Additional support has been received from the Universities and Research Secretariat, Ministry of Business and Knowledge of the Catalan Government under the grant no. 2017-SGR-892. JDG holds a “Ramón y Cajal” fellowship (RYC-2013-13054). EMA-U is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities - Spanish State Research Agency (RYC2018-026053-I). NV-T is funded by a post-doctoral grant, Juan de la Cierva Programme (FJC2018-038085-I), Ministry of Science and Innovation–Spanish State Research Agency. OG-R is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (FJCI-2017-33437), and receives funding from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Fellowship Program (2019-AARF-644568). ASV is the recipient of an Instituto de Salud Carlos III Miguel Servet II fellowship (CP II 17/00029). HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2018-02532), the European Research Council (#681712), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-720931), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809-2016862), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL. KB is supported by the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#RDAPB-201809-2016615), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (#AF-742881), Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2017-0243), the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement (#ALFGBG-715986), and European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2019-466-236). MSC receives funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 948677). MSC also receives funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI19/00155) and from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Juan de la Cierva Programme grant IJC2018-037478-I).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MMA, JDG, EAU, MSC, and JLM developed the study design and conception of the presented idea. MMA, MS, GS, GO, JDG, EAU, CF, NVT, JMG, OG, ASV, GSB, ANB, AP, MS, GK, HZ, and KB contributed to data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation. CM and KF managed and coordinated samples. MMA and MSC drafted the manuscript, and MSC and JLM supervised the project and contributed to the writing of the final version of the manuscript. All the co-authors critically reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approvals and consent to participate

The ALFA+ study (ALFA-FPM-0311) was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee “Parc de Salut Mar”, Barcelona, and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02485730). All participating subjects signed the study’s informed consent form that had also been approved by the Independent Ethics Committee “Parc de Salut Mar”, Barcelona.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

MS is a full-time employee of the Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. GK is a full-time employee of the Roche Diagnostics GmbH. HZ has served at scientific advisory boards for Denali, Roche Diagnostics, Wave, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Pinteon Therapeutics, and CogRx; has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Fujirebio, Alzecure, and Biogen; and is a co-founder of the Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work). KB has served as a consultant, at advisory boards, or at data monitoring committees for Abcam, Axon, Biogen, JOMDD/Shimadzu, Julius Clinical, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers and is a co-founder of the Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. MSC has served as a consultant and at advisory boards for the Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. and has given lectures in symposia sponsored by the Roche Diagnostics, S.L.U, and Roche Farma, S.A. JLM is currently a full-time employee of H. Lundbeck A/S and priory has served as a consultant or at advisory boards for the following for-profit companies, or has given lectures in symposia sponsored by the following for-profit companies: Roche Diagnostics, Genentech, Novartis, Lundbeck, Oryzon, Biogen, Lilly, Janssen, Green Valley, MSD, Eisai, Alector, BioCross, GE Healthcare, and ProMIS Neurosciences. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Confusion table of group prevalence for each low burden definition. Table S2. CSF biomarker levels by Aβ group including CSF biomarkers extreme values. Table S3. Structural MRI measurements by Aβ group. Table S4. FDG PET measurements by Aβ group. Fig. S1. Comparison of all CSF biomarkers between Aβ groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Milà-Alomà, M., Shekari, M., Salvadó, G. et al. Cognitively unimpaired individuals with a low burden of Aβ pathology have a distinct CSF biomarker profile. Alz Res Therapy 13, 134 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00863-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00863-y