Abstract

Background

Cognition is closely associated with physical function. Although high brain amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition and neurofilament light chain (NfL) are associated with cognitive and gait speed decline, relationships of combined plasma Aβ and NfL profiles with cognitive and physical functions in older adults remain unknown. The research aim of this study was to investigate the prospective associations of combined plasma Aβ and NfL profiles with cognitive and physical functions in older adults.

Methods

Participants (n = 452, aged 76 ± 5 years) who had both plasma Aβ and NfL data collected from the Multidomain Alzheimer’s Preventive Trial (MAPT, May 2008 to April 2016) were included in the current study. These participants were from four MAPT groups (multidomain interventions [physical activity and nutritional counselling, and cognitive training], omega-3 supplementation, multidomain plus omega-3 supplementation and control group) and had received a 3-year intervention, followed by a 2-year observational follow-up. Cognitive function was evaluated as Mini-Mental State Examination and composite cognitive score (CCS, a mean Z-score combining four cognitive tests). Physical function was evaluated as gait speed (4-m usual-pace walk test) and chair-stand time (5-time maximal chair-stand test). Cognitive and physical function data measured at the time of and after blood Aβ and NfL tests were used for analysis. Participants with plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios lower than 0.107 and NfL levels greater than 93.04 pg/ml were classified as Aβ+ and NfL+. Multivariable regressions and mixed-effects linear models were used for the analysis.

Results

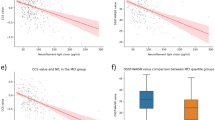

At the cross-sectional level, no significant association was found between Aβ+NfL+ and cognitive or physical function after controlling for age, sex, body mass index, education level and MAPT group. Evaluating longitudinal changes, participants with Aβ+NfL+ had greater annual declines in the CCS (β = − 0.11, 95%CI [− 0.17, − 0.05]) and gait speed (β = − 0.03, 95%CI [− 0.05, − 0.005]). After adjusting for APOE ɛ4 genotype, Aβ+NfL+ was associated with a greater decline only in the CCS (β = − 0.09, 95%CI [− 0.15, − 0.02]).

Conclusions

Combined low plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and high plasma NfL level was associated with greater declines in cognition and gait speed over time, providing further evidence of the links between cognitive and physical function.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Decreased physical function has been associated with cognitive impairment in older adults [1, 2]. Multiple studies have examined the association between physical function and brain biomarkers of neurodegeneration, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and neurofilament light chain (NfL). Higher brain Aβ burden, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and NfL levels are associated with slower gait speed [3,4,5] and greater gait variability [6]. Yet, no association was found with chair-stand [7]. Considering the close connection between brain and plasma biomarkers, it is plausible to think that plasma Aβ and NfL concentrations might also be associated with physical function. However, no study has been performed to examine this association in an older population. Meanwhile, a recent research by de Wolf et al. [8] has reported that adults with both low plasma Aβ42 and high NfL levels demonstrated a higher risk of developing dementia or AD than those with one biomarker condition (i.e. low Aβ42 or high NfL). Therefore, a combined plasma Aβ and NfL condition might be associated with declines in both cognitive and physical functions. The objective of this study is to explore the possible association between combined plasma Aβ and NfL condition with the evolution of physical function in older adults.

Methods

The Multidomain Alzheimer’s Preventive Trial (MAPT, ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT00672685]) was a randomized, controlled trial that compared multidomain interventions (physical activity and nutritional counselling and cognitive training) and omega-3 supplementation, combined or alone, with a placebo control group [9]; no effects of the MAPT interventions on cognitive function and gait speed over a 3-year period were found [10]. MAPT was approved by the ethics committee in Toulouse (CPP SOOM II). Written consent forms were obtained from all participants.

Study population

Older adults (70 years or over) with spontaneous memory complaints or limitations in at least one instrumental activity of daily living or a gait speed lower than 0.8 m/s were recruited in the MAPT. Our current study included 452 participants who had available information on plasma Aβ and NfL levels.

Evaluation of cognitive and physical functions

Cognitive function was evaluated as Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, ranging from 0 to 30, higher is better) and composite cognitive score (CCS), which was calculated as a mean Z-score combining four cognitive tests (free and total recall of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, ten MMSE orientation items, the Digit Symbol Substitution Test score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised and the Category Naming Test) [10]. Physical function was evaluated as gait speed, which was measured by a 4-m usual-pace walk test (m/s), and chair-stand time (s), which was measured by a 5-repetition maximal speed chair-stand test. Outcome measures were evaluated at baseline, the 6th month and each year during the 3-year intervention period and the 2-year observational follow-up. Data of outcome measures collected at the same time point and after blood tests were used in this study.

Measurement of plasma Aβ and NfL levels

Plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels were assessed by immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry as previously described [11]. Aβ levels were analysed and calculated by integrated peak area ratios to known concentrations of the internal standards using the Skyline software package [12]. Plasma NfL levels were measured using the R-PLEX human neurofilament L antibody set (Meso Scale Discovery, F217X). Samples were diluted 2-fold in a diluent buffer and tested in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasma Aβ or NfL levels were measured once using blood samples collected in the first or second year of the study. For most participants (n = 420 out of 452), Aβ and NfL levels were measured from blood samples taken at the 1-year wave of data collection. For the rest of the participants, plasma markers were measured using samples from the second year. Blood samples were collected on the same day as cognitive and physical function evaluation.

Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and NfL stratification

The selection of Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio cut-off value was performed based on participants (n = 201) who underwent amyloid [18F] florbetapir positron emission tomography (PET positive when standardized uptake value ratios ≥ 1.17) [13] using logistic regression (PET positive/negative as the dependent variable and Aβ42/Aβ40 as the independent variable) with Youden’s Index as the metric (higher is better) [11]. The cut-off value of NfL was determined as the upper quartile of our participants. Participants with low Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios (≤ 0.107) and high NfL levels (≥ 93.04 pg/ml) were classified as Aβ+NfL+.

Covariates

Age, sex, body mass index (kg/m2), education level and MAPT group. Since almost 10% of the participants did not have APOE ɛ4 genotype data, separate models were performed with and without APOE ɛ4 genotype (dichotomous variable) as an additional covariate.

Statistics

Descriptive data was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or absolute numbers with percentage, as appropriate. Comparisons between the Aβ+NfL+ group and the rest of the population were performed with Student’s t test and chi-square test, as appropriate.

Multivariable linear regression was used for cross-sectional analyses with cognitive or physical functions (separate models) measured at the moment of the blood test as dependent variables and Aβ+NfL+ as the independent variable of interest. Longitudinal analyses were performed using separated mixed-effects linear models with longitudinal data of cognitive or physical functions as dependent variables. A random effect at the participant level and a random slope of time were assumed. All analyses were controlled for the covariates mentioned above and were performed using SAS 9.4. p values were corrected for multiple testing by Benjamini–Hochberg procedure [14], with a significance level of 0.05, in cross-sectional and longitudinal models with and without APOE ɛ4 genotype, separately.

Results

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The average age of our participants was 76 years, and 59% of the participants were female. ninety-three per cent of the participants had plasma biomarkers tested from blood samples collected 1 year after the enrolment of the MAPT. Participants with plasma Aβ+NfL+ were older and had lower CCS than the other participants.

The cross-sectional analysis did not show any significant association between plasma Aβ+NfL+ and cognitive or physical function after controlling for covariates (Table 2).

Longitudinal analysis showed that participants with plasma Aβ+NfL+ had greater declines in CCS and gait speed over time. After adjusting for APOE ɛ4 genotype, Aβ+NfL+ was still associated with greater declines in CCS while no significance in gait speed was found (Table 3). No significant associations were found between Aβ+NfL+ status and MMSE or chair-stand. For the covariates, the MAPT intervention groups were not significantly associated with cognitive or physical functions.

Discussion

This study focused on the association between the combined plasma Aβ and NfL condition and cognitive and physical functions in older adults over a nearly 4-year period. We report for the first time that older adults with combined low plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios and high NfL levels had more declines in cognitive (detected in CCS but not MMSE) and physical functions (detected in gait speed but not chair rise) over time while no cross-sectional association was found. Such findings indicate the feasibility of using plasma biomarkers to estimate the progressive decline of cognitive and physical functions in older adults over time.

Previous studies have reported the association between cognition and each of the biomarkers analysed in our research. Yaffe [15] analysed the baseline plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and a 10-year longitudinal cognition data in older adults (average age of 74 years) and reported that lower Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was associated with greater cognitive decline. A similar longitudinal association between plasma NfL and cognition was also found in the study of Mielke et al. [16], who analysed the cognition data over a 15- or 30-month period in older adults with a median age of 76 years. Notably, no cross-sectional association between plasma biomarkers and cognition was found in both studies mentioned above. Our results based on combined plasma Aβ and NfL condition further confirmed these cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Moreover, our findings are consistent with previous studies which reported that greater longitudinal cognitive declines were associated with higher plasma NfL levels in older adults with abnormal brain Aβ conditions (e.g. low CSF Aβ and high brain Aβ deposition) [17, 18].

Additionally, we further extend the literature by showing that the plasma Aβ+NfL+ profile was associated with the longitudinal decline of gait speed, but not chair-stand. These results are in line with our previous findings (based on the same MAPT dataset) about brain Aβ deposition and physical function, which reported that greater brain Aβ burden was associated with lower gait speed [3], but not chair rise [7]. Other researchers have also reported that high CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, NfL level and Aβ burden in the brain subregions were associated with increased gait variability [6] and low gait speed [4, 5], while similar studies for plasma Aβ and NfL are lacking. The difference in associations between gait speed and chair-stand with the plasma biomarkers in our study might be related to the various mechanisms behind those two physical functions. Chair-stand performance is more dependent on lower limb muscle function (strength and power) than gait speed; the latter is a more complex movement which involves dynamic balance control, coordination and muscle function. The significant association between plasma biomarkers and gait speed, but not chair-stand, indicates that these neurodegeneration-related biomarkers might be connected with the neural aspect of gait speed, such as cognitive status [19], motor control [20] and muscle synergies [21]. Since plasma NfL is closely associated with axonal damage [22] and plasma Aβ is associated with CSF Aβ [23], which is involved in synaptic function and multiple signalling pathways (e.g. calcium signalling and insulin-like growth factor-I signalling) [24], the less favourable plasma NfL and Aβ condition (i.e. Aβ+NfL+) might suggest structural and functional changes in the nervous system at a fundamental level. Consequently, besides cognitive degeneration, structural and functional changes in motor-related brain regions and peripheral neural pathways might also lead to gait speed decline. Therefore, further studies are still needed to explore the association between plasma biomarkers and the structural or functional changes in the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Notably, although Aβ+NfL+ was associated with gait speed decline, such decline has not reached the clinically meaningful threshold of 0.05 m/s [25]. Further studies are also needed to examine if the cognitive decline in CCS is clinically meaningful.

Our study only examined the initial plasma Aβ and NfL combined condition with cognitive and physical functions while previous studies have demonstrated the close associations between overtime biomarker changes and changes in cognitive performance. A 10-year follow-up study by Okereke et al. [26] on late middle-aged adults (average age of 64 years) reported that with a 1 SD (standard deviation) increase in the change of plasma Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio, there was a 0.02-unit/year more decline in global cognitive score. A recent study by Mattson et al. [27] has shown that increased plasma NfL levels over time were associated with larger global cognitive decline. Yet, the association between longitudinal biomarker changes and physical function remains to be established and needs further exploration.

Limitation

We analysed data from a randomized controlled trial. Although there are no significant differences in plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios and NfL levels among the MAPT groups, the MAPT interventions might affect plasma Aβ and NfL levels which were tested based on blood samples collected at the first/second year of the study. Therefore, it would be more appropriate if observational data were used. Since the longitudinal biomarker data were not available in our study, we could not confirm if there was any change in the combined Aβ and NfL status over the 4-year period. Moreover, the absence of longitudinal data of the biomarkers impeded us from looking at the association between changes in biomarkers and changes in cognitive and physical functions.

Conclusions

Our results suggest the possibility of using easily accessible plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and NfL profiles as combined biomarkers to estimate declines in cognition and gait speed over time. Further studies on other cohorts are still needed to examine the reliability of the plasma biomarker cut-off values (identified in this study) for the classification of Aβ+NfL+ status. Based on the combined plasma Aβ+NfL+ status, the incidence of neurological disorders, such as dementia and AD, can be further studied. Moreover, the association between Aβ+NfL+ status and the structural changes of motor-related brain regions can be examined to understand if the physical function changes found in our study is related to changes in motor-related central nervous system.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-β

- CCS:

-

Composite cognitive score

- MAPT:

-

Multidomain Alzheimer’s Preventive Trial

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NfL:

-

Neurofilament light chain

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

References

Auyeung TW, Kwok T, Lee J, Leung PC, Leung J, Woo J. Functional decline in cognitive impairment - the relationship between physical and cognitive function. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:167–73.

Gure TR, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Piette JD, Plassman BL. Functional limitations in older adults who have cognitive impairment without dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26:78–85.

del Campo N, Payoux P, Djilali A, Delrieu J, Hoogendijk EO, Rolland Y, et al. Relationship of regional brain β-amyloid to gait speed. Neurology. 2016;86:36–43.

Nadkarni NK, Perera S, Snitz BE, Mathis CA, Price J, Williamson JD, et al. Association of brain amyloid-β with slow gait in elderly individuals without dementia: influence of cognition and apolipoprotein E ε4 genotype. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:82.

Mielke MM, Syrjanen JA, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Skoog I, Vemuri P, et al. Comparison of variables associated with cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament, total-tau, and neurogranin. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1437–47.

Koychev I, Galna B, Zetterberg H, Lawson J, Zamboni G, Ridha BH, et al. Aβ42/Aβ40 and Aβ42/Aβ38 ratios are associated with measures of gait variability and activities of daily living in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. JAD. 2018;65:1377–83.

de Souto BP, Cesari M, Rolland Y, Salabert AS, Payoux P, Andrieu S, et al. Cross-sectional and prospective associations between β-amyloid in the brain and chair rise performance in nondementia older adults with spontaneous memory complaints. Gerona. 2017;72:278–83.

de Wolf F, Ghanbari M, Licher S, McRae-McKee K, Gras L, Weverling GJ, et al. Plasma tau, neurofilament light chain and amyloid-β levels and risk of dementia; a population-based cohort study. Brain. 2020;143:1220–32.

Vellas B, Carrie I, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Touchon J, Dantoine T, Dartigues JF, et al. Mapt study: a multidomain approach for preventing Alzheimer’s disease: design and baseline data. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2014;1:13–22.

Andrieu S, Guyonnet S, Coley N, Cantet C, Bonnefoy M, Bordes S, et al. Effect of long-term omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:377–89.

Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Li Y, Gordon BA, et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008081.

Pino LK, Searle BC, Bollinger JG, Nunn B, MacLean B, MacCoss MJ. The Skyline ecosystem: informatics for quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics. Mass Spec Rev. 2017; [cited 2020 Apr 8]; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/mas.21540.

Gabelle A, Jaussent I, Bouallègue FB, Lehmann S, Lopez R, Barateau L, et al. Reduced brain amyloid burden in elderly patients with narcolepsy type 1: amyloid load in narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:74–83.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300.

Yaffe K. Association of plasma β-amyloid level and cognitive reserve with subsequent cognitive decline. JAMA. 2011;305:261.

Mielke MM, Syrjanen JA, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Vemuri P, Skoog I, et al. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology. 2019;93:e252–60.

Hu H, Chen K-L, Ou Y-N, Cao X-P, Chen S-D, Cui M, et al. Neurofilament light chain plasma concentration predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in nondemented elderly adults. Aging. 2019;11 [cited 2020 May 19]. Available from: http://www.aging-us.com/article/102220/text?_escaped_fragment_=.

Ou Y-N, Hu H, Wang Z-T, Xu W, Tan L, Yu J-T, et al. Plasma neurofilament light as a longitudinal biomarker of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci Adv. 2019;5:94–105.

Peel NM, Alapatt LJ, Jones LV, Hubbard RE. The association between gait speed and cognitive status in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol Ser A. 2019;74:943–8.

Reimann H, Fettrow T, Thompson ED, Jeka JJ. Neural control of balance during walking. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1271.

Chvatal SA, Ting LH. Common muscle synergies for balance and walking. Front Comput Neurosci. 2013;7 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fncom.2013.00048/abstract.

Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, Piehl F, Sormani MP, Gattringer T, et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:577–89.

Cho SM, Kim HV, Lee S, Kim HY, Kim W, Kim TS, et al. Correlations of amyloid-β concentrations between CSF and plasma in acute Alzheimer mouse model. Sci Rep. 2015;4:6777.

Parihar MS, Brewer GJ. Amyloid-β as a modulator of synaptic plasticity. JAD. 2010;22:741–63.

Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults: meaningful change and performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–9.

Okereke OI, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Grodstein F. Ten-year change in plasma amyloid β levels and late-life cognitive decline. Arch Neurol. 2009;66 [cited 2020 Sep 8]. Available from: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archneurol.2009.207.

Mattsson N, Cullen NC, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:791.

Acknowledgements

The MAPT study was supported by grants from the Gérontopôle of Toulouse, the French Ministry of Health (PHRC 2008, 2009), Pierre Fabre Research Institute (manufacturer of the omega-3 supplement), ExonHit Therapeutics SA, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals Inc. The promotion of this study was supported by the University Hospital Center of Toulouse. The data sharing activity was supported by the Association Monegasque pour la Recherche sur la maladie d’Alzheimer (AMPA) and the INSERM-University of Toulouse III UMR 1027 Unit.

The members of the MAPT/DSA study group are:

MAPT Study Group

Principal investigator: Bruno Vellas (Toulouse); Coordination: Sophie Guyonnet; Project leader: Isabelle Carrié; CRA: Lauréane Brigitte; Investigators: Catherine Faisant, Françoise Lala, Julien Delrieu, Hélène Villars; Psychologists: Emeline Combrouze, Carole Badufle, Audrey Zueras; Methodology, statistical analysis and data management: Sandrine Andrieu, Christelle Cantet, Christophe Morin; Multidomain group: Gabor Abellan Van Kan, Charlotte Dupuy, Yves Rolland (physical and nutritional components), Céline Caillaud, Pierre-Jean Ousset (cognitive component), Françoise Lala (preventive consultation). The cognitive component was designed in collaboration with Sherry Willis from the University of Seattle, and Sylvie Belleville, Brigitte Gilbert and Francine Fontaine from the University of Montreal.

Co-investigators in associated centres: Jean-François Dartigues, Isabelle Marcet, Fleur Delva, Alexandra Foubert, Sandrine Cerda (Bordeaux); Marie-Noëlle-Cuffi, Corinne Costes (Castres); Olivier Rouaud, Patrick Manckoundia, Valérie Quipourt, Sophie Marilier, Evelyne Franon (Dijon); Lawrence Bories, Marie-Laure Pader, Marie-France Basset, Bruno Lapoujade, Valérie Faure, Michael Li Yung Tong, Christine Malick-Loiseau, Evelyne Cazaban-Campistron (Foix); Françoise Desclaux, Colette Blatge (Lavaur); Thierry Dantoine, Cécile Laubarie-Mouret, Isabelle Saulnier, Jean-Pierre Clément, Marie-Agnès Picat, Laurence Bernard-Bourzeix, Stéphanie Willebois, Iléana Désormais, Noëlle Cardinaud (Limoges); Marc Bonnefoy, Pierre Livet, Pascale Rebaudet, Claire Gédéon, Catherine Burdet, Flavien Terracol (Lyon), Alain Pesce, Stéphanie Roth, Sylvie Chaillou, Sandrine Louchart (Monaco); Kristelle Sudres, Nicolas Lebrun, Nadège Barro-Belaygues (Montauban); Jacques Touchon, Karim Bennys, Audrey Gabelle, Aurélia Romano, Lynda Touati, Cécilia Marelli, Cécile Pays (Montpellier); Philippe Robert, Franck Le Duff, Claire Gervais, Sébastien Gonfrier (Nice); Yannick Gasnier and Serge Bordes, Danièle Begorre, Christian Carpuat, Khaled Khales, Jean-François Lefebvre, Samira Misbah El Idrissi, Pierre Skolil, Jean-Pierre Salles (Tarbes).

MRI group: Carole Dufouil (Bordeaux), Stéphane Lehéricy, Marie Chupin, Jean-François Mangin, Ali Bouhayia (Paris); Michèle Allard (Bordeaux); Frédéric Ricolfi (Dijon); Dominique Dubois (Foix); Marie Paule Bonceour Martel (Limoges); François Cotton (Lyon); Alain Bonafé (Montpellier); Stéphane Chanalet (Nice); Françoise Hugon (Tarbes); Fabrice Bonneville, Christophe Cognard, François Chollet (Toulouse).

PET scans group: Pierre Payoux, Thierry Voisin, Julien Delrieu, Sophie Peiffer, Anne Hitzel, (Toulouse); Michèle Allard (Bordeaux); Michel Zanca (Montpellier); Jacques Monteil (Limoges); Jacques Darcourt (Nice).

Medico-economics group: Laurent Molinier, Hélène Derumeaux, Nadège Costa (Toulouse).

Biological sample collection: Bertrand Perret, Claire Vinel, Sylvie Caspar-Bauguil (Toulouse).

Safety management: Pascale Olivier-Abbal.

DSA Group:

Sandrine Andrieu, Christelle Cantet, Nicola Coley.

Funding

The present work was performed in the context of the Inspire Program, a research platform supported by grants from the Region Occitanie/Pyrénées-Méditerranée (Reference number: 1901175) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (Project number: MP0022856), and received additional funds from Alzheimer Prevention in Occitania and Catalonia (APOC Chair of Excellence - Inspire Program).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

LH analysed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. PSB interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. GA, ADN and JEM are members of the NfL testing team and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. YL and RJB are members of the Aβ testing team and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. BV revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The MAPT was approved by the ethics committee in Toulouse (CPP SOOM II). Written consent forms were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Participants consented for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., de Souto Barreto, P., Aggarwal, G. et al. Plasma Aβ and neurofilament light chain are associated with cognitive and physical function decline in non-dementia older adults. Alz Res Therapy 12, 128 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00697-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00697-0