Abstract

Background

Brain amyloid deposition and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are associated with complex neuroinflammatory reactions such as microglial activation and cytokine production. Glucose metabolism is closely related to neuroinflammation. Ketogenic diets (KDs) include a high amount of fat, low carbohydrate and medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) intake. KDs lead to the production of ketone bodies to fuel the brain, in the absence of glucose. These nutritional interventions are validated treatments of pharmacoresistant epilepsy, consequently leading to a better intellectual development in epileptic children. In neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline, potential benefits of KD were previously pointed out, but the published evidence remains scarce. The main objective of this review was to critically examine the evidence regarding KD or MCT intake effects both in AD and ageing animal models and in humans.

Main body

We conducted a review based on a systematic search of interventional trials published from January 2000 to March 2019 found on MEDLINE and Cochrane databases. Overall, 11 animal and 11 human studies were included in the present review. In preclinical studies, this review revealed an improvement of cognition and motor function in AD mouse model and ageing animals. However, the KD and ketone supplementation were also associated with significant weight loss. In human studies, most of the published articles showed a significant improvement of cognitive outcomes (global cognition, memory and executive functions) with ketone supplementation or KD, regardless of the severity of cognitive impairments previously detected. Both interventions seemed acceptable and efficient to achieve ketosis.

Conclusion

The KD or MCT intake might be promising ways to alter cognitive symptoms in AD, especially at the prodromal stage of the disease. The need for efficient disease-modifying strategies suggests to pursue further KD interventional studies to assess the efficacy, the adherence to this diet and the potential adverse effects of these nutritional approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Carbohydrates represent the primary energy source for the brain. However, when glucose is not readily available (e.g. starvation), a metabolic switch occurs in favour of ketone bodies (KB), usually released by the liver. The diets specifically designed for KB production are called ketogenic diets (KDs) [1, 2]. They are the first and only nutritional interventions that enabled a significant reduction in the incidence of seizures in pharmacoresistant epilepsy [3] or in chronic cluster headaches [4]. The core characteristics of the KD are the association of a high amount of fat, with low carbohydrate intake, usually a macronutrient ratio of fat to protein and carbohydrate combined equal to 3–4:1. Alternative KDs were developed using ketone supplementation (KS), in which fats are provided with medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) intake. Their common objective is to achieve ketosis, leading to reduced insulin secretion and glycaemia within 48 h, as well as a shift in the brain’s metabolism [2].

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), it is described numerous interrelations between abnormal glucose metabolism and the occurrence of brain lesions. First, AD could be a partial consequence of insulin resistance, which affects insulin signalling and favours in the brain abnormal deposition of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau (pTau) accumulation, leading in turn to cognitive decline [5]. Furthermore, the expression of apolipoprotein E allele 4 (APOE4) is a common risk factor for AD and for type 2 diabetes suggesting a common pathophysiological background [6]. As demonstrated by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), abnormal brain glucose metabolism in the temporal and parietal lobes occurs from the earliest stages in AD animal models and AD patients but also in asymptomatic individuals at risk for AD [7]. Interestingly, these hypometabolic regions are still able to take up KB, even though they can no longer utilize glucose [8].

At the cellular level, several KD neuroprotective effects have been observed, linked to various mechanisms: (i) reduction of the concentration of several excitatory neurotransmitters (e.g. glutamate) [9], (ii) stabilization of synaptic functions due to enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis [10] and (iii) reduction of reactive oxygen species generation and increase adenosine triphosphate availability [11]. Moreover, KB have specific protective effects against cerebral Aβ toxicity and cell damage as shown in rat cultured hippocampal neurons [12]. Aβ can induce neuroinflammation, which is a current therapeutic target in AD. KD could modulate Aβ toxicity by promoting the action of endogenous anti-inflammatory molecules such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, leading to a decreased systemic inflammation [13].

These observations, as well as the current lack of success of anti-AD therapies or nutritional interventions to change the course of AD, suggest that KD or KS might be of therapeutic interest in these patients. A potential benefit of KDs in AD was already claimed in media and some scientific reports [14, 15]. However, as few works have brought about a critical review of existing data, we hereby propose a comprehensive and translational review of KD efficiency in both preclinical and clinical AD or ageing studies. Thus, the main objective of this review was to assess the effects of ketogenic interventions on clinical and metabolic outcomes (e.g. cognitive function, brain metabolism) or AD biomarkers, both in experimental animals and in humans. We will also examine the potential side effects of ketogenic interventions in these populations, in terms of nutritional change and adverse effects.

Research process

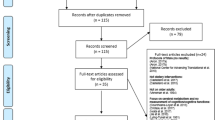

We performed a systematic search in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. We identified all published articles between January 2000 and March 2019 on MEDLINE and Cochrane databases using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “ketogenic diet” or “medium-chain triglyceride” and assorted combinations of the following terms: “Alzheimer’s disease”, “Alzheimer”, “cognition” and/or “memory”. We only included interventional studies using either KD or KS. We have excluded studies published in languages other than English, focusing on KD diet effects in diseases other than AD or performed in cellular models. Titles and abstracts were the base of the initial screening. We evaluated the eligibility of selected articles after full-text readings. We also examined all papers cited in the selected articles. We added additional references, based on their originality and/or relevance regarding the scope of this review. Data extraction was performed by six authors (ML, BP, EC, FML, JH, CP), using a standardized extraction form. This tool assessed the study design, population (number of animals/participants, animal model/ageing individuals or AD patients), type of ketogenic intervention, outcomes (e.g. biological endpoint, clinical endpoint, neuroimaging endpoint), follow-up duration, nutritional changes and potential side effects due to the intervention. This search was carried out in April 2019.

Results

Among one hundred forty-six selected papers, we identified 84 interventional studies. Two additional interventional studies were found through the bibliography of the relevant animal studies papers. In total, 22 (11 animal studies and 11 human studies) were considered relevant for the present review. We summarized details of animal and human studies in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 1 outlines the results of the systematic searches.

Preclinical studies

Two types of interventions were used: KD (N = 7) either ad libitum or calorie-controlled, and KS (N = 4), compared to control diet or placebo, respectively. Even if the total number of animals varied from one study to the other (from 16 to 65 with a mean of 48.5 ± 5.2 animals), the number in each treatment group was nearly the same. Overall, baseline age at the start, species or AD model type, sex and follow-up duration varied between studies.

Ageing animals

Five studies assessed ketogenic interventions in ageing animals. The mean age at baseline varied depending on the studied species: 9 years for beagle dogs (N = 1), above 20 months for wild-type (WT) rats (N = 3) and 12 months for WT mice (N = 1). Only two studies out of five compared young (4-month-old WT rats) vs ageing animals [20, 21]. Three studies used only ageing male rodents [20, 23, 27] whereas two other studies compared the effect of KD/KS on ageing males and females [21, 24]. The follow-up duration was different according to species: 8 or 12 weeks for WT rats [20, 21, 27], 32 weeks for beagle dogs [24] and 72 weeks for old WT mice on which the effect of KD on life span was evaluated [23].

Alzheimer’s disease animal models

Six studies included different AD mouse models, based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Briefly, 3xTgAD mice [22, 25], APP/PS1 mice [17, 18], APP [V7171] mice [26] and APP+PS1 [19] mice were used. Interestingly, Brownlow et al. choose to compare an amyloid-based AD model (APP+PS1 mice) and a tau-based AD model (Tg4510 AD mice) [19]. One of these studies used only female AD mouse model (APP [V7171]) [26]. Regarding baseline age, 3xTgAD mice were older (8.5 months) than APP [V7171] (3 months), APP/PS1 (between 1 and 3 months) and APP+PS1 and Tg4510 mice (5 months). The follow-up duration varied from 4 to 32 weeks (mean 17 ± 5.05 weeks) without a link between duration and a type of AD model.

Outcomes and results

The following objectives were assessed: efficacy on cognition and/or motor functions (N = 3 assessing both, N = 5 assessing cognition only, N = 1 assessing motor function only), impact on neuropathological AD lesions (N = 5), KD safety (N = 1) and weight variations (N = 9). Eight studies (one in old WT mice, two in young vs ageing WT rats and five in AD mouse models) evaluated multiple outcomes.

In ageing animals

Three studies evaluated the effects of KD in ageing animals, either on safety and cognition [23], weight and neurotransmitter function [20] or cognition/motor function and neurotransmitter function [21].

Effects of KD/KS on life expectancy and mortality

Only Newman et al. conducted a long-term study of KD. They showed that KD was able to reduce mid-life mortality but without improving maximum lifespan in old C57Bl6 WT mice [23].

Cognitive and motor impact of KD/KS

Four studies evaluated the cognitive impact of KD and showed a positive effect on cognition, in ageing animals [20, 23, 24, 27]. This effect was observed with several KD formulae (two calorie-controlled KD, two KS). This result suggests that brain metabolism can shift towards the use of KB, regardless of the kind of ketone-oriented diet used, with potential cognitive gain. Similarly, motor performances were improved in all studies, regardless of potential associated cognitive benefits. These results are consistent with many mouse studies demonstrating that keto-adaptation enhanced the capacity to transport and metabolize fat as well as motor abilities and recovery [39,40,41].

Mechanisms underlying cognitive effects of KD and KS

Hernandez et al. studied the effect of KD on transport protein expression in the brain of ageing mice, notably vesicular glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporters [20, 21]. They observed that KD ad libitum was able to reverse the age-dependent decrease of vesicular GABA transporter expression in the hippocampus and in the prefrontal cortex. This result could be linked to the known effect of KD in epilepsy [3]. Indeed, KD enhances GABA vesicular filling which maintains an inhibitory feedback associated with the beneficial effect of KD. One can also hypothesize that this effect on GABA may have a potential anxiolytic effect. Interestingly, the authors described a similar reversal effect on the age-dependent decrease of vesicular glutamate transporter expression that was not restricted to the hippocampus.

In addition, Wang and Mitchell described that KS is associated, in old WT rats, with an increase in insulin receptor 1 levels and Akt phosphorylation and a decrease in ribosomal protein S6 kinase phosphorylation [27]. KS effect on this pathway is associated with increased ube3a expression that notably plays a role in synaptic stabilization. Conversely, Newman et al. identified a downregulation of the insulin pathway in old WT mice fed with KD ad libitum [23]. The conflicting results of the two studies can be due to the discrepancies concerning the duration of diet (8 vs 72 weeks) and/or the baseline age of the animals (21 vs 12 months). So far, data are not sufficient to conclude on the mechanisms responsible for the cognitive impact of KD/KS in ageing brain or whether there even is an impact. However, if there is an effect of KD/KS on cognition, one first hypothesis might be synaptic protection through neurotransmitter pathway and/or synaptic stabilizations.

Effects of KD/KS on weight

Two studies [20, 27] showed a significant weight loss while no body weight modifications were observed in the two others [23, 24]. Among the four, only Hernandez et al. observed a significant weight loss despite a calorie-controlled KD. This effect was specific to old WT rats, but an unexpected fat mass reduction was observed both in young and old WT rats [20].

In Alzheimer’s disease animal models

In details, five studies using AD mouse models assessed cognition and/or motor function together with histological data [17,18,19, 22, 26] while one assessed both impacts on weight and histology [24].

Cognitive and motor impact of KD/KS

Two studies assessed the cognitive impact of KD in AD mouse models [17, 22]. Mice only showed a cognitive gain in the latter study, in which triheptanoin was added to KD. According to the authors, the cognitive gain was likely to result from an enhanced mitochondrial function, due to triheptanoin supplementation [17]. In the other study, motor coordination was significantly improved in the KD group.

Effects of KD/KS on AD pathological lesions

Five studies specifically assessed the changes in Aβ and/or tau deposition in AD mouse models [17,18,19, 22, 26]. Kashiwaya et al. and Van der Auwera et al. described a decrease in Aβ deposition in the brain of KD-fed female APP [V7171] and male 3xTgAD mice, respectively. In addition, Kashiwaya et al. reported a significant reduction of abnormal pTau labelling in the hippocampal neurons of 3xTgAD mice under a calorie-controlled KD. On the other hand, Aso et al., Beckett et al. and Brownlow et al. failed to report any significant improvement in brain amyloid load after KD in APP/PS1 [17, 18], APP+PS1 and Tg4510 (tau) AD mouse models [19].

Several factors or combined factors could explain this discrepancy, but we will focus on the two mains: (i) type of diet and/or its duration and (ii) type of AD model and time course of lesion onset. Regarding diet, the duration of the intervention might have played a role in the observed discrepancy. Indeed, this effect on Aβ accumulation and pTau pathology in 3xTgAD mice was described when an animal received a KS for 32 weeks [22]. This result may also be due to a specific therapeutic effect of the synthetic ketone ester (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-(R)-1,3-butanediol monoester, administered as a dietary supplement.

The choice of an AD mouse model is crucial in this setting. All AD mouse models used are based on the overexpression of Aβ, but they differed in terms of the type and/or the pathological time course of the disease. Thus, promoters regulating the mutated gene expression are model-dependent and so is Aβ production and accumulation. AD models with high Aβ production and accumulation like 3xTgAD (combining amyloidopathy and tauopathy) or APP [V7171] (early-onset familial AD) were the ones in which the effect of the ketogenic interventions was observed [22, 26]. KD, like calorie-restricted diet, might induce insulin-degrading enzymes directed against Aβ [42]. Accordingly, an effect on Aβ accumulation based on degradation is easier to observe in animals with higher Aβ accumulation. In addition, the time course of the lesions depends on model types. Therefore, if the aim of the intervention is to evaluate the effect on Aβ load, the intervention has to take into account this parameter. For example, in APP/PS1 mice, soluble Aβ became detectable from 3 months onward and amyloid plaques appeared at 9 months. Studying the effect of KD/KS before those milestones or with an early endpoint may lead to the absence of observed effect [17, 18]. It is also interesting to note that the type of promoter also affects the magnitude of Aβ load. For example, the prion protein promoter, present in APP+PS1 and APP/PS1, is responsible for a more widespread and less selective Aβ expression than others [43]. Localization of amyloid brain load may differ from one animal model to the other, and analyzing methods have to be adapted. Thus, analysis restricted to specific brain regions (e.g. Aβ immunochemical labelling in the prefrontal cortex or hippocampus [24]) seems to be more efficient than global analysis (e.g. whole-brain enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay against total Aβ and APP C-terminal [25]).

Regarding other abnormal features in models of AD, Aso et al. showed a reduction of neuroinflammation after intake of KD + triheptanoin in APP/PS1 mouse that was not observed in APP/PS1 mouse fed with KD only and thus might be specific to triheptanoin supplementation [17]. Pawlosky et al. observed that KS induced a reduction of the free radical insult against hippocampal proteins and modified both α- and β-secretase expression levels (higher and lower respectively) in hippocampal but not in cortical lysates [25]. KS is able to reduce the levels of hippocampal BACE 1, a key enzyme in the production of Aβ peptide, and this finding could explain the reduction of amyloid load.

Overall, KD and KS seemed to be able to reduce Aβ and pTau load as well as neuroinflammation, especially in aggressive mouse models treated for a long time. In some models, those neuropathological effects were associated with improvement of cognitive and/or motor functions. While the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated, these observations support the hypothesis that KD/KS might have definite therapeutic actions on AD abnormal biological pathways.

Effects of KD/KS on weight

Four studies, using various methodologies, observed a significant weight loss [18, 22, 25, 26], while no body weight modifications were observed in the last one [19]. Thus, while these studies used variable material and approaches, most of them found a reproducible weight loss induced by KD or KS. However, details are lacking to draw definite conclusions on the mechanisms of this weight loss and its consequences on the safety of this approach. There was no reported association of weight loss to cognitive change in these studies.

Clinical studies

General characteristics of the studies

Included humans studies (N = 11) are presented in Table 2. They involved either ageing subjects with or without mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (N = 6; mean age 66.1 to 75.4 years old; mean Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score at baseline 17.1 to 27.1) or individuals with AD dementia based on clinical diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV or the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (N = 5). In addition, these studies comprised inconsistent sex ratios (30 to 66% of male). Five of them indicated an average level of education between 12.5 and 15.3, and only one provided information about the ethnic groups of the study population (mostly Caucasians in 91%).

Thus, participants showed various degrees of cognitive performance among studies, from normal ageing people to moderate dementia. Two studies did not specify the degree of cognitive impairment of their participants [33, 36]. One can notice that the use of Aβ or tau biomarkers, highly recommended for increasing diagnostic accuracy, was not mentioned in these studies. APOE genotyping was performed in four studies only [28, 30, 37, 38].

Regarding nutritional interventions, two studies used a classic KD approach while 11 relied on KS using MCT. Of note, KS protocols differed much in composition and daily dose (20 to 56 g of MCT per day). Two studies had a crossover design [29, 38] while one did not include a control group [31]. The seven remaining studies were randomized controlled trials. The number of individuals included varied among studies from 6 to 152 (mean 31.3 ± 38.2). Likewise, the follow-up durations were rather short and heterogeneous, from 0 to 26 weeks (mean 11.2 ± 9) including three studies examining the immediate effect, the same day as the clinical and cognitive examination of KS [28, 30, 37, 38].

None of the studies included in this review provided details on patients’ medical conditions. Apart from cognitive impairment, comorbidities are likely to modulate the efficacy or the adhesion to KD or KS. For instance, in patients with type 2 diabetes, very stringent KD may not be sustainable over long-term, although there is no formal contraindication to it [44]. Besides inflammatory diseases, mood disorders, chronic pain and polypharmacy may change the nutritional status of the individuals, as well as the safety of a high-fat diet. Moreover, only Abe et al. presented its exclusion criteria: subjects with body mass index < 23 kg/m2 or major organ dysfunction [32]. Altogether, this impairs the external validity of the studies and pleads for new studies that would assess the interaction between comorbidities and KD/KS in patients.

Outcomes

All studies but one assessed cognitive changes after KS or KD. One study focused on cognitive changes and the feasibility of long-term KS in cognitively impaired individuals [29]. However, the instruments used to assess cognitive outcomes were inconsistent among studies. Five studies used the Mini-Mental Status Examination [28, 31, 32, 34, 38], and four of them utilized the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) [31, 35, 37, 38]. Two studies used a neuroimaging (PET) endpoint: regional cerebral blood flow [30] or [11C]-acetoacetate tracer [28].

Metabolic effects of KD/KS in cognitively impaired patients and older adults

Nine studies out of eleven monitored the plasma levels of KB to make sure that participants actually achieved ketosis. Thus, the authors were able to demonstrate that ketosis was quickly and efficiently reached in all the studies, regardless of the type of intervention. However, only five studies examined the changes in nutritional status or body composition in patients under KS/KD [28, 31, 32, 35, 36]. Krikorian et al. highlighted a mean weight loss of 4 kg per individual after 6 weeks, in MCI adults under KD as compared to patients under control diet [36]. This finding is consistent with the results of a meta-analysis showing that KD is commonly associated with weight loss, due to reduced total calorie intake [45].

Three other studies did not show any significant weight change with KS [28, 31, 35]. Interestingly, Abe et al. observed that participants improved their muscle mass and function [32]. Of note, those subjects received vitamin D and leucine in addition to the nutritional intervention, which may have contributed to this anabolic effect.

Finally, only four studies reported on the side effects of KS/KD [28, 31, 36, 37], including the study by Henderson et al. that described gastrointestinal symptoms (49%), which led to treatment discontinuation (23% in the intervention group).

Cognitive effects of KD/KS

Apart from the Torosyan et al. study (no clinical endpoint) [30], the majority of the studies (six out of ten) observed significant cognitive improvements in the intervention groups (KS or KD), regardless of participants’ cognitive status (from MCI to severe AD patients). On the other hand, the three remaining studies did not report any significant effect on cognition [28, 34, 35]. Cunnane et al. previously mentioned that given a choice between glucose and ketones, neurons would rather consume the latter [8]. Besides, even though brain-imaging studies revealed that brain utilization of glucose declines in early AD, KB utilization does not [46]. The results of the two PET imaging studies evaluated for this review were consistent with these findings [28, 30]. Interestingly, Torosyan et al. showed a long-term increase in brain metabolism after KS in non-APOE4 individuals [30]. This is in line with the results of three studies included in this review that highlighted better efficiency of KS in non-APOE4 subjects [30, 37, 38]. There is also an established relationship between APOE4 genotype and brain amyloid deposition. It is noteworthy to say that in the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomized-controlled trial, non-APOE4 genotype was associated with greater improvement of the MMSE and Clock Drawing Test scores when following a Mediterranean diet rather than a Western-type diet [47]. Thus, the relationship between APOE4 status and cognitive effects of metabolic interventions deserves further investigations.

Limitations of the studies

Despite the interesting findings of these 13 studies, many limitations must be acknowledged. First, studies appear highly heterogeneous, in particular regarding age, gender ratios or participants’ cognitive status, which all have a significant effect on the risk of subsequent cognitive decline. These limitations prevent from drawing robust conclusions about the cognitive benefits of the ketogenic interventions. Some results may also be questionable such as an unexpected cognitive decline measured with the ADAS-cog scale under placebo after only 45 days in MCI individuals whereas in the intervention group, participants maintained their cognitive level [37].

The short follow-up durations and the repeated cognitive assessments are likely to be responsible for a retest effect especially in cognitively intact or MCI individuals. Conversely, patients with mild-to-moderate dementia may be too severely impaired to observe benefits from an intervention. This observation was previously raised when discussing the failure of anti-amyloid therapies in AD [48]. Furthermore, all studies aimed at measuring short-term changes in cognition or brain metabolism. The absence of long-term follow-up did not provide any insight into the persistence of cognitive changes after discontinuation of the nutritional intervention. Adhesion to the KD or to KS intake must be carefully examined as far as long-term nutritional changes are expected. Besides, the monitoring of potential adverse effects is mandatory, especially in AD, since nutritional status is a key predictor of rapid cognitive decline as well as functional limitations [49]. Finally, the small number of studies published so far raises the issue of a potential publication bias as negative studies on the effects of KS or KD on cognition could not be published.

Conclusion

Despite the growing interest for KD in AD over the last years, only few interventional studies in animals or humans clearly addressed the subject. In preclinical studies, this review pointed out some interesting results such as improvement of cognition and motor function in some AD mouse model or ageing animals. The mechanisms leading to a benefic effect on cognition could be due to the (i) modification in neurotransmitter transport pathway and/or synaptic maintenance in ageing WT animals and (ii) improvement of abnormal features (Aβ load or neuroinflammation) in AD mouse models. However, we must keep in mind that KD was initially created (and is still popular) for inducing weight loss in healthy or overweighed adults. In cognitively impaired subjects, older adults or animal studies, it was also often associated with a significant weight loss. This consequence could play an adverse effect on muscle performance (sarcopenia) or even on cognitive decline. In humans, notwithstanding the high heterogeneity of the studies and methodological issues discussed above, most of the published studies could suggest improved cognitive outcomes (memory, executive function or global cognition) with KS or KD, regardless of the severity of cognitive impairment. Both interventions seemed acceptable for included subjects and show efficacy to achieve ketosis. KD and KS intake both offer different features and potential benefits. They also present different disadvantages. KD might be difficult to start in older adults with modern eating habits and even more difficult to maintain. KS are useful to achieve ketosis but do not lead to the same metabolic shift, since the brain is still being fueled by glucose.

As a conclusion, the KD might be a promising way to fight against the cognitive symptoms of AD, especially from the prodromal stage of the disease (MCI). Regarding the body of evidence discussed above, the hypothesis that KD could postpone cognitive decline in AD should be explored. Unlike omega-3 supplements or Ginkgo biloba, the ketogenic interventions have not been evaluated yet in large sample randomized controlled trials with sufficient follow-up and structured cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes. Therefore, further studies are warranted, in particular, in adults with early AD, not only to assess the efficiency of the KD on cognitive decline, but also to examine the adverse effects (e.g. weight loss, malnutrition) as well as the adherence to the diet.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

β-Amyloid peptide

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAS-cog:

-

Alzheimer Disease Assessment

- ADCS-CGIC:

-

Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Scale Clinical Global Impression of Change

- APOE4:

-

Apolipoprotein E allele 4

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- BACE 1:

-

Beta-secretase 1

- cal ctrl:

-

Calorie-controlled

- CD:

-

Control diet

- DST:

-

Digit Symbol Test

- FDG:

-

Flurodeoxyglucose

- FU:

-

Follow-up

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GI:

-

Gastro-intestinal

- KB:

-

Ketone bodies

- KD:

-

Ketogenic diet

- KS:

-

Ketone supplementation

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MCT:

-

Medium-chain triglyceride

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject heading

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental Status Examination

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PS:

-

Presenilin

- pTau:

-

Phosphorylated tau

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TMT:

-

Trail Making Test

- vitD:

-

Vitamin D

- WT:

-

Wild-type

References

Boison D. New insights into the mechanisms of the ketogenic diet. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:187–92.

Vidali S, Aminzadeh S, Lambert B, Rutherford T, Sperl W, Kofler B, et al. Mitochondria: the ketogenic diet--a metabolism-based therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;63:55–9.

Martin-McGill KJ, Jackson CF, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN. Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD001903.

Di Lorenzo C, Coppola G, Di Lenola D, Evangelista M, Sirianni G, Rossi P, et al. Efficacy of modified Atkins ketogenic diet in chronic cluster headache: an open-label, single-arm, clinical trial. Front Neurol. 2018;9:64.

Matsuzaki T, Sasaki K, Tanizaki Y, Hata J, Fujimi K, Matsui Y, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with the pathology of Alzheimer disease: the Hisayama Study. Neurology. 2010;75:764–70.

El-Lebedy D, Raslan HM, Mohammed AM. Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism and risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:12.

Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria and cell bioenergetics: increasingly recognized components and a possible etiologic cause of Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1434–55.

Cunnane SC, Courchesne-Loyer A, Vandenberghe C, St-Pierre V, Fortier M, Hennebelle M, et al. Can ketones help rescue brain fuel supply in later life? Implications for cognitive health during aging and the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:53.

Noh HS, Hah Y-S, Nilufar R, Han J, Bong J-H, Kang SS, et al. Acetoacetate protects neuronal cells from oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:702–9.

Bough KJ, Wetherington J, Hassel B, Pare JF, Gawryluk JW, Greene JG, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the anticonvulsant mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:223–35.

Masino SA, Kawamura M, Wasser CD, Wasser CA, Pomeroy LT, Ruskin DN. Adenosine, ketogenic diet and epilepsy: the emerging therapeutic relationship between metabolism and brain activity. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:257–68.

Kashiwaya Y, Takeshima T, Mori N, Nakashima K, Clarke K, Veech RL. d-β-hydroxybutyrate protects neurons in models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5440–4.

Jeong EA, Jeon BT, Shin HJ, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim HJ, et al. Ketogenic diet-induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation decreases neuroinflammation in the mouse hippocampus after kainic acid-induced seizures. Exp Neurol. 2011;232:195–202.

Broom GM, Shaw IC, Rucklidge JJ. The ketogenic diet as a potential treatment and prevention strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2019;60:118–21.

Włodarek D. Role of ketogenic diets in neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease). Nutrients. 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010169.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Aso E, Semakova J, Joda L, Semak V, Halbaut L, Calpena A, et al. Triheptanoin supplementation to ketogenic diet curbs cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice used as a model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10:290–7.

Beckett TL, Studzinski CM, Keller JN, Paul Murphy M, Niedowicz DM. A ketogenic diet improves motor performance but does not affect β-amyloid levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2013;1505:61–7.

Brownlow ML, Benner L, D’Agostino D, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Ketogenic diet improves motor performance but not cognition in two mouse models of Alzheimer’s pathology. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75713.

Hernandez AR, Hernandez CM, Campos KT, Truckenbrod LM, Sakarya Y, McQuail JA, et al. The antiepileptic ketogenic diet alters hippocampal transporter levels and reduces adiposity in aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:450–8.

Hernandez AR, Hernandez CM, Campos K, Truckenbrod L, Federico Q, Moon B, et al. A ketogenic diet improves cognition and has biochemical effects in prefrontal cortex that are dissociable from hippocampus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:391.

Kashiwaya Y, Bergman C, Lee J-H, Wan R, King MT, Mughal MR, et al. A ketone ester diet exhibits anxiolytic and cognition-sparing properties, and lessens amyloid and tau pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1530–9.

Newman JC, Covarrubias AJ, Zhao M, Yu X, Gut P, Ng C-P, et al. Ketogenic diet reduces midlife mortality and improves memory in aging mice. Cell Metab. 2017;26:547–57 e8.

Pan Y, Larson B, Araujo JA, Lau W, de Rivera C, Santana R, et al. Dietary supplementation with medium-chain TAG has long-lasting cognition-enhancing effects in aged dogs. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1746–54.

Pawlosky RJ, Kemper MF, Kashiwaya Y, King MT, Mattson MP, Veech RL. Effects of a dietary ketone ester on hippocampal glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and amino acids in a 3xTgAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2017;141:195–207.

Van der Auwera I, Wera S, Van Leuven F, Henderson ST. A ketogenic diet reduces amyloid beta 40 and 42 in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr Metab. 2005;2:28.

Wang D, Mitchell ES. Cognition and synaptic-plasticity related changes in aged rats supplemented with 8- and 10-carbon medium chain triglycerides. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160159.

Fortier M, Castellano C-A, Croteau E, Langlois F, Bocti C, St-Pierre V, et al. A ketogenic drink improves brain energy and some measures of cognition in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2019;15:625–34.

Ota M, Matsuo J, Ishida I, Takano H, Yokoi Y, Hori H, et al. Effects of a medium-chain triglyceride-based ketogenic formula on cognitive function in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019 Jan 18;690:232–6.

Torosyan N, Sethanandha C, Grill JD, Dilley ML, Lee J, Cummings JL, et al. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow associated with a 45 day course of the ketogenic agent, caprylidene, in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized, double-blinded, pilot study. Exp Gerontol. 2018;111:118–21.

Taylor MK, Sullivan DK, Mahnken JD, Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Feasibility and efficacy data from a ketogenic diet intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement N Y N. 2018;4:28–36.

Abe S, Ezaki O, Suzuki M. Medium-chain triglycerides in combination with leucine and vitamin D benefit cognition in frail elderly adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2017;63:133–40.

Ota M, Matsuo J, Ishida I, Hattori K, Teraishi T, Tonouchi H, et al. Effect of a ketogenic meal on cognitive function in elderly adults: potential for cognitive enhancement. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:3797–802.

Ohnuma T, Toda A, Kimoto A, Takebayashi Y, Higashiyama R, Tagata Y, et al. Benefits of use, and tolerance of, medium-chain triglyceride medical food in the management of Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective, open-label pilot study. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:29–36.

Rebello CJ, Keller JN, Liu AG, Johnson WD, Greenway FL. Pilot feasibility and safety study examining the effect of medium chain triglyceride supplementation in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. BBA Clin. 2015;3:123–5.

Krikorian R, Shidler MD, Dangelo K, Couch SC, Benoit SC, Clegg DJ. Dietary ketosis enhances memory in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:425 e19–27.

Henderson ST, Vogel JL, Barr LJ, Garvin F, Jones JJ, Costantini LC. Study of the ketogenic agent AC-1202 in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Nutr Metab. 2009;6:31.

Reger MA, Henderson ST, Hale C, Cholerton B, Baker LD, Watson GS, et al. Effects of beta-hydroxybutyrate on cognition in memory-impaired adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:311–4.

Huang Q, Ma S, Tominaga T, Suzuki K, Liu C. An 8-week, low carbohydrate, high fat, ketogenic diet enhanced exhaustive exercise capacity in mice part 2: effect on fatigue recovery, post-exercise biomarkers and anti-oxidation capacity. Nutrients. 2018;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10101339.

Ma S, Huang Q, Tominaga T, Liu C, Suzuki K. An 8-week ketogenic diet alternated interleukin-6, ketolytic and lipolytic gene expression, and enhanced exercise capacity in mice. Nutrients. 2018;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111696.

Ma S, Huang Q, Yada K, Liu C, Suzuki K. An 8-week ketogenic low carbohydrate, high fat diet enhanced exhaustive exercise capacity in mice. Nutrients. 2018;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060673.

Wang J, Ho L, Qin W, Rocher AB, Seror I, Humala N, et al. Caloric restriction attenuates beta-amyloid neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2005;19:659–61.

Hall AM, Roberson ED. Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88:3–12.

Bolla AM, Caretto A, Laurenzi A, Scavini M, Piemonti L. Low-carb and ketogenic diets in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11050962.

Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, Keller U, Yancy WS, Brehm BJ, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:285–93.

Castellano C-A, Nugent S, Paquet N, Tremblay S, Bocti C, Lacombe G, et al. Lower brain 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake but normal 11C-acetoacetate metabolism in mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2015;43:1343–53.

Martínez-Lapiscina EH, Galbete C, Corella D, Toledo E, Buil-Cosiales P, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Genotype patterns at CLU, CR1, PICALM and APOE, cognition and Mediterranean diet: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial. Genes Nutr. 2014;9:393.

Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M. Why do trials for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:735–9.

Sanders CL, Wengreen HJ, Schwartz S, Behrens SJ, Corcoran C, Lyketsos CG, et al. Nutritional status is associated with severe dementia and mortality: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32:298–304.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML and BP analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. EC, JH and FML critically reviewed the selected studies and revised the manuscript accordingly. CP conceived the original idea, reviewed the selected studies and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lilamand, M., Porte, B., Cognat, E. et al. Are ketogenic diets promising for Alzheimer’s disease? A translational review. Alz Res Therapy 12, 42 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00615-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00615-4