Abstract

Background

Computerized neuropsychological tests for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have attracted increasing interest. Memory for faces and proper names is a complex task because its association is arbitrary. It implicates associative occipito-temporal cerebral regions, which are disrupted in AD. The short form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME-12), developed to detect preclinical and prodromal AD, asks individuals to learn the names and occupations associated with 12 faces. The current work advances this field by using voice recognition and touchscreen response format. The purpose of this study is to create the first self-administered episodic memory test, FACEmemory®, by adapting the FNAME-12 for tablet use with voice recognition, touchscreen answers, and automatic scoring. The test was minimally supervised by a psychologist to avoid technological problems during execution and scored manually to assess the reliability of the automatic scoring. The aims of the present study were (1) to determine whether FACEmemory® is a sensitive tool for the detection of cognitive impairment, (2) to examine whether performances on FACEmemory® are correlated with those on the S-FNAME (paper-and-pencil version with 16 images), and (3) to determine whether performances on FACEmemory® are related to AD biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Aβ42, p-tau, and Aβ42/p-tau ratio).

Methods

FACEmemory® was completed by 154 cognitively healthy (CH) individuals and 122 subjects with mild cognitive impairment, of whom 61 were non-amnestic (naMCI) and 61 amnestic (aMCI). A subsample of 65 individuals completed the S-FNAME, and 65 subjects received lumbar punctures.

Results

Performance on FACEmemory® was progressively worse from CH to the naMCI and aMCI groups. A cutoff of 31.5 in total FACEmemory® obtained 80.5% and 80.3% sensitivity and specificity values, respectively, for discriminating between CH and aMCI. Automatically corrected FACEmemory® scores were highly correlated with the manually corrected ones. FACEmemory® scores and AD CSF biomarker levels were significantly correlated as well, mainly in the aMCI group.

Conclusions

FACEmemory® may be a promising memory prescreening tool for detecting subtle memory deficits related to AD. Our findings suggest FACEmemory® performance provides a useful gradation of impairment from normal aging to aMCI, and it is related to CSF AD biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

One of the endophenotypes proposed for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is episodic memory tests [1]. Cognitive approaches conceptualizing face-name associative memory have demonstrated that associating unfamiliar faces with proper names is a task more complex than other visual memory tests because this is an arbitrary association [2]. It implicates associative occipito-temporal cerebral regions with extensive connections to cortical areas, which is the specific neural function disrupted in AD [3, 4]. The Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME) [4] was developed to detect preclinical AD. The FNAME is an associative episodic memory test that has been validated in American [5] and Spanish [6] populations. Patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have lower performances on the FNAME than cognitively healthy (CH) individuals [7]. Moreover, low scores on the original and Spanish (S-FNAME) versions of the FNAME have been found to be associated with biomarker evidence of increased cerebral amyloid burden, quantified by positron emission tomography in healthy elderly [4, 8].

A shortened and optimized version of the FNAME (FNAME-12), whose scores are strongly correlated with those on the original FNAME (r = 0.77), was recently created [9] and subsequently validated in American [9], Latino American [10], and Greek populations [11]. In contrast with the original FNAME, the FNAME-12 comprises fewer stimuli, an additional learning trial, and a delayed memory recognition task. This shortened version can be used not only in preclinical AD, but also in prodromal AD, making it possible to discriminate between normal aging and MCI [9], with the latter group converting to dementia in most cases [12, 13]. However, the FNAME-12 retains the main features of the original FNAME: a paired associative learning paradigm and its ecological validity to test the difficulty in retrieving newly learned face-name pairs frequently complained among elderly people. The FNAME-12 was modified to include an additional learning trial and a recognition task.

In the last decade, computerized neuropsychological tests have generated increasing interest in clinical practice contexts [14], especially for early detection of AD. For this reason, the FNAME was recently self-administered, without supervision, to 49 CH individuals aged between 60 and 87 years, as part of a Computerized Cognitive Composite for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease (C3-PAD) test with a touchscreen. A majority completed the test successfully [15].

Other computerized neuropsychological tools, such as the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) [16], comprise memory tests that can be administered with a touchscreen tablet. A bad performance on its episodic memory subtest, the Paired Associates Learning (PAL), has been found to be associated with AD biomarkers, such as reduced hippocampal volume and increased levels of total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [1]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no verbal episodic memory tests that can be self-administered on a tablet computer with voice recognition and a touchscreen and then automatically scored, registered, and saved in a database.

For the purpose of the present study in Fundació ACE, we developed a self-administered computerized version of the FNAME-12 (named FACEmemory®) with images, names, and occupations representative of the Spanish population. The test was administered using a tablet computer with voice recognition and a touchscreen, enabling us to immediately score and register the results in a database, as a tool for the early detection of cognitive impairment and AD. We hypothesized that FACEmemory® would identify individuals with early cognitive impairment at risk of developing AD, as well as providing immediate scoring and ensuring maximum standardization and reliability.

The main objectives of the present study were the following: (1) to determine whether FACEmemory® was a sensitive tool for the detection of cognitive impairment, (2) to assess whether performances on FACEmemory® were correlated with those on the S-FNAME (paper-and-pencil version with 16 images), and (3) to determine whether performances on FACEmemory® were related to AD biomarkers in CSF (amyloid beta 42 [Aβ42], p-tau, and Aβ42/p-tau ratio).

Methods

Participants

A sample of 276 individuals older than 50 years participated in this study: 154 CH individuals and 122 subjects diagnosed with MCI, of whom 61 were non-amnestic (naMCI) and 61 amnestic (aMCI). All of them were evaluated at Fundació ACE, Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades (Barcelona, Spain), a non-profit Alzheimer’s institution that provides diagnostic, treatment, and patient management services to the Catalan Public Health Service [17]. All participants underwent a complete neuropsychological assessment using the Neuropsychological Battery of Fundació ACE (NBACE), whose normative data and cutoff scores have been reported elsewhere [18]; a neurological history and examination; a semi-structured psychosocial interview, including a functionality assessment by the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (BDRS) [19, 20]; and a diagnosis of their cognitive status by the clinical team from the Memory Unit at a daily consensus conference [17]. The sample comprised 64 participants enrolled in the Fundació ACE Healthy Brain Initiative (FACEHBI) study [21], 58 participants in the BIOFACE cohort, 42 individuals recruited from the Open House Initiative (OHI) [22], and 112 subjects evaluated at Fundació ACE’s Memory Unit.

The inclusion criteria for the whole sample were the following: age over 50, an educational level of at least elementary school (in order to ensure the correct understanding of the FACEmemory® instructions), a clinical diagnosis of CH or MCI [17], and completion of FACEmemory®.

The clinical diagnoses for the CH group were as follows: absence of objective cognitive impairment, with average or above-average scores on NBACE [18, 23]; normal general cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 27) [24, 25]; a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [26] of 0; and no history of functional impairment due to declining cognition, with a score below 4 on the BDRS [19, 20].

The clinical diagnosis for the MCI group were as follows: subjective cognitive complaints, essentially preserved general cognitive function (MMSE score ≥ 24) [24, 25], preserved performance in activities of daily living (BDRS < 4) [19, 20], absence of dementia; a CDR [26] of 0.5, an objectively measurable impairment in memory or another cognitive function (aMCI or naMCI) [12, 27], and the absence of prescribed symptomatic treatment for dementia (i.e., acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine).

Participants were not required to have previous knowledge of tablet computer use. To ensure the correct understanding of the FACEmemory® instructions and the completion of the test, exclusion criteria included an educational level below elementary school and significant auditory or visual abnormalities, such as glaucoma, cataracts, or severe aphasia.

As mentioned above, a subsample of 65 individuals was also administered the S-FNAME (paper-and-pencil version with 16 items). That is, they completed FACEmemory® and S-FNAME on different days (no more than 2 months apart).

Finally, 65 subjects underwent lumbar puncture (LP) to measure AD biomarkers in CSF.

In collaboration with Dr. Rentz’s team, we transformed the original paper-and-pencil FNAME-12 [9] into a self-administered computerized version (named FACEmemory®) with images, names, and occupations representative of the Spanish population. The test was administered using a tablet computer with voice recognition and touchscreen, enabling us to immediately score and register the results anonymously in a database. The scores of all variables ranged from 1 to 12, and the total FACEmemory® scores ranged from 1 to 96.

The FACEmemory® procedure

All subjects completed FACEmemory® on a tablet with voice recognition, a touchscreen, and scoring registration in Fundació ACE. The temporal sequence of FACEmemory® was the following: two learning trials, a short-term memory task, and a long-term memory task that included face, name, and occupation recognition. The total test duration was approximately 30 min.

After the study, participants completed a satisfaction survey to indicate their level of satisfaction with the test. The survey consisted of 5 questions and required the participants to score their satisfaction from 1 to 5 (1 being the worst score), to choose what aspect of the test they disliked the most, to indicate whether they would recommend the test to family or friends, to select what aspect they liked the most, and to mention whether they would like to repeat the test in the future.

FACEmemory® was self-administered with minimal supervision from a psychologist (who only addressed technological issues). The psychologist simultaneously scored the test manually to determine whether the automatic scoring matched the hand scoring.

As shown in Fig. 1, the first learning trial consisted of a total of 12 faces, each one associated with a name and an occupation that appeared beneath it for 8 s. The second learning trial was identical, except that the faces appeared in a different order. The participants were instructed to read the name and occupation appearing beneath each face aloud and to try to remember it. Then, the application asked the participants to press the red microphone button and to say the name (LN1/LN2) and occupation (LO1/LO2) they remembered as being associated with each face. If they did not remember anything, they were allowed to say “I don’t know.”

The FACEmemory® procedure. The participants underwent two exposures (learning 1 and learning 2) to all the 12 face, name, and occupation groupings. Following each exposure, they were asked to give the name (LN1/LN2) and the occupation (LO1/LO2) associated with each face. After a 2-min delay, they were asked to provide the name (RSN) and the occupation (RSO) associated with each face. Following a 20-min delay, they were asked to identify the previously learned face from two pictures (FR). They were again asked to give the name (RLN) and the occupation (RLO) associated with each face. The participants were asked to select the name and/or occupation associated with the face from among three items (REN/REO)

For the evaluation of short-term memory, 2 min after the second learning trial, the application again asked the participants to say the name (RSN) and occupation (RSO) they remembered as being associated with each face, but if they did not remember anything, they could say “I don’t know.” They had to press the red microphone button and to answer.

Finally, 20 min after the second learning trial (LN2/LO2), the application started the long-term memory assessment, which involved free recall and recognition tasks. First, the participants were instructed to recognize, out of 3 faces, the face that had appeared in the first learning trial and to touch it (FR). Then, the correct face appeared, and the application asked the participants to say the name (RLN) and occupation (RLO) they remembered for each face. After each answer, a screen appeared, showing the right face and 2 rows beneath it. Each row had 3 name and 3 occupation options. The participants were instructed to touch the name (REN) and occupation (REO) they remembered as being associated with that face.

The application registered the touched responses and the voice of the participants automatically and entered the scores into a database anonymously.

Application development

The application was developed with Android language and using Google Books for voice recognition and interactions with the device. Google voice recognition libraries were used, as they are the most complete and because they allow the use of different languages.

During development, screens were constantly checked to ensure they were clear, so that the user’s attention would not be distracted while they were learning the data presented and so that the test would be as reliable as possible. The application has been designed so that when the user interacts with it using voice commands, the elements that appear on the screen are minimal. The FACEmemory® application is linked to a control panel or back end, from which the saved data from all the tests performed can be viewed and extracted, and filtered by date or test. Access to the back end requires a username and password.

One of the most important features of the FACEmemory® application is that it keeps the user’s data completely anonymous for better protection. Despite this anonymity, the application is configured so that a user can perform multiple tests at different times. When a participant finishes FACEmemory®, the application generates a code Fundació ACE saves on a separate system that complies with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and that connects the user to the test carried out. Therefore, there are data saved from individual tests or tests related to others saved in the system, but no personal data, thus complying with the GDPR at all times. Security and data encryption measures have been also applied to communications between system elements, to make both the tablet application and the back office safe and robust.

In summary, the FACEmemory® application allows the user to focus their attention on the test, as well as allowing Fundació ACE to manage the data in a simple and anonymous way.

Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid collection

This protocol followed the consensus recommendations established by the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Standardization Initiative [28]. Briefly, those participants who agreed to undergo a LP in Fundació ACE had the procedure performed by an experienced neurologist, with the patients in a seated position and under fasting conditions. After applying local anesthesia (1% mepivacaine) subcutaneously, the neurologist obtained CSF by LP in the intervertebral space of L3–L4. The fluid was collected passively in two 10-ml polypropylene tubes (Stardest Ref. 62610018). The first tube was analyzed externally for basic biochemistry (glucose, total proteins, proteinogram, and cell type and number). The second tube was centrifuged (2000×g 10 min at 4 °C), and the fluid was aliquoted into polypropylene tubes (Stardest Ref. 72694007) and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. The time delay between CSF collection and storage was less than 2 h.

On the day of the analysis, the aliquots were thawed at room temperature and vortexed for 5–10 s to determine AD biomarkers in CSF [29]. One aliquot/patient was used to determine the concentrations of Aβ1-42, t-tau, and p181-tau using the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Innotest, Fujirebio Europe) at the Research Laboratory of Fundació ACE.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) was used to compare sociodemographic data between the CH, naMCI, and aMCI groups. An ANOVA adjusted by years of formal education, age, and sex (ANCOVA) was carried out to compare FACEmemory® scores between the CH, naMCI, and aMCI groups.

Logistic regression analyses were carried out to search for discrimination indexes, in which the diagnostic comparisons between CH/MCI, CH/aMCI, and CH/naMCI individually were the dependent variables, and the total FACEmemory® score was the independent variable. Moreover, diagnostic sensitivities, specificities, and total FACEmemory® cutoff, as measured by the analysis of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, were obtained for the purpose of discriminating between CH/MCI and CH/aMCI. Cutoff points for the whole sample were established by calculating the sensitivity and specificity for the total FACEmemory® score. ROC analysis was used to calculate the optimal cutoff value between CH and the MCI and aMCI groups. Moreover, to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the cutoff score, an area under the curve (AUC) analysis was also carried out and yielded a confidence interval of 95%. Our goal was to obtain an AUC greater than 0.75 for the total FACEmemory® variable and for the sensitivity and specificity values.

To ensure the reliability of the automatic scoring, Pearson’s correlation analyses were carried out between hand and automatic (obtained from voice recognition/touchscreen) scorings of the FACEmemory® test. We also correlated performances on FACEmemory® with those on the S-FNAME (paper-and-pencil version with 16 items) to examine convergent validity. Finally, partial correlation analyses were performed between the FACEmemory® scores and CSF AD biomarkers, adjusting for age, sex, and education.

Results

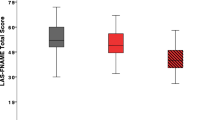

The CH, naMCI, and aMCI groups were statistically similar in terms of age and sex. However, the participants from the CH group had a significantly higher education than those from the MCI group (Table 1). An ANCOVA, adjusted by education, showed that the total FACEmemory® score significantly differed between the groups, with the aMCI group obtaining worse scores (Fig. 2). As detailed in Table 2, all FACEmemory® subscores differed significantly between the groups.

With regard to discrimination indexes, logistic regression analyses, controlling for education, showed that the total FACEmemory® score significantly discriminated between the CH and MCI (naMCI + aMCI), naMCI, and aMCI groups. The best sensitivity and specificity values were obtained when the CH and aMCI groups were contrasted (82% and 80%, respectively) (Table 3).

The total FACEmemory® cutoffs were reported after we ensured that the AUC was greater than 0.75 and identified the cutoff score that yielded approximately equal sensitivity and specificity values (see Table 4).

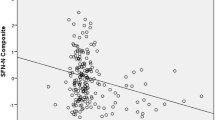

Manual and automatic scores of the total FACEmemory® were found to be highly correlated (r = 0.98, p < 0.001) in the whole sample. A significant correlation (r = 0.69, p < 0.0001) between both tests was found in the subsample of 65 subjects who completed FACEmemory® and the S-FNAME.

Participants who underwent a LP (n = 65) (16 CH, 28 naMCI, and 21 aMCI) were significantly older than those who did not (mean/SD = 63.89/6.56, 68.59/8.23, respectively, t = 4.74, p < 0.001), but both groups were similar in terms of sex (37% and 40% men, respectively, chi square = 0.19, p = 0.66), education (mean/SD = 11.65/4.18, 11.66/4.27, respectively; t = − 0.03, p = 0.98), and FACEmemory® performance (mean/SD = 36.60/21.67, 39.20/19.65, respectively; t = 0.91, p = 0.36). For this reason, partial correlations between total FACEmemory® scores and AD biomarker levels in CSF were controlled for age. In the whole sample, total FACEmemory® scores were significantly correlated with Aβ42 (r = 0.33), Aβ42/p-tau ratio (r = 0.50), t-tau (r = − 0.44), and p-tau (r = − 0.43) levels. However, when analyses were stratified by the diagnostic group, the highest correlation values were obtained in the aMCI group, between FACEmemory® performance and Aβ42 (r = 0.62) and Aβ42/p-tau ratio (r = 0.68) levels. By contrast, no statistically significant correlations were found between FACEmemory® performance and CSF biomarker levels in the CH group (for details, see Table 5).

The results of the satisfaction survey showed that 65.2% of the participants (n = 180) scored 5 (excellent), 23.2% (n = 64) 4 (very good), 9.4% (n = 26) 3 (good), 1.8% (n = 5) 2 (medium), and 0.4% (only one) 1 (bad). The mean satisfaction score was 4.51 (SD = 0.77) points, and there were no significant differences among the CH (mean/SD, 4.58/0.63), aMCI (4.30/0.99), and naMCI (4.50/0.99) groups; F(2, 217) = 2.91, p = 0.06. When participants were asked whether they would recommend the test to a friend or a relative, most of them (94.2%) answered “yes” and a few (5.8%) answered “no”; most of them (97%) confirmed they would be willing to repeat the test in the future.

Discussion

The results of the present study reveal that the self-administered computerized FACEmemory®, conducted under minimal supervision to avoid technological problems, might be a useful tool for the early detection of AD. In this study, its sensitivity and specificity values were adequate, confirming its capacity to discriminate between CH and MCI, mainly the amnestic type. As expected, performances on the computerized FACEmemory® were related to the manual scoring of FACEmemory® and the Spanish version of its original paper-and-pencil test (S-FNAME) [4, 6], confirming that it is an associative episodic memory tool with highly reliable scoring. Moreover, performances on FACEmemory® were related to CSF biomarker levels, mainly in the aMCI group, indicating that FACEmemory® is related to AD biomarkers, such as Aβ42 and Aβ42/p-tau ratio.

The novelty of the present study is that FACEmemory® is the first self-administered verbal episodic memory test application with voice recognition and touchscreen. These features ensure the standardization of the administration and scoring, and registration of performance data related to, a sensitive tool for determining memory impairment. The test is correlated with CSF markers of AD neurodegeneration.

In the search for new memory endophenotypes of AD, the present study has examined a computerized adaptation of a face-name task [9]. Attention to these endophenotypes has been relatively lacking compared to the attention given to biomarkers. AD is a specific disease of a neuroplasticity mechanism related to the fundamental role of the amyloid precursor protein in episodic memory encoding. AD-related biomarkers, including neuroimaging, CSF, or plasma, whether related to Aβ, microtubule-associated protein tau, or another biochemical abnormality, are secondary to the attack of AD pathology on an episodic memory-encoding mechanism in the brain [30]. Accordingly, measures of episodic memory, the function most vulnerable to AD’s pathological processes, are of prime importance for the early detection of AD-related dysfunction and follow-up of the disease progression [1, 12].

The FNAME was created [4] in an attempt to detect subtle memory deficits in individuals with preclinical AD and validated in its original version [5], in Greek [11], in Latino American [10], and in Spanish [6] populations. Consistent with the findings of Rentz et al. [4, 5], our team found that the S-FNAME is sensitive to episodic memory [6, 7] and related to amyloid burden, as measured by 18F-florbetaben positron emission tomography in healthy elderly [7]. Since faces represent information encoded by the non-dominant (usually right) hemisphere and names (and occupations) are information encoded by the language areas of the brain, the dominant (usually left) hemisphere, their combination requires communication between the two hemispheres across the corpus callosum [3]. Thus, this tool provides a strong test of functions highly vulnerable to the AD process in both hemispheres of the brain.

In contrast to paper-and-pencil tests, computerized neuropsychological tests have benefits that make them suitable for early detection of cognitive changes in the elderly, such as minimization of ceiling effects through management of test difficulty, standardized administration and item presentation, accurate response recordings, prompt and automated scoring, and reduced administration costs [31, 32]. Moreover, in contrast to FACEmemory®, computerized memory tests mostly depend on recognition rather than free recall, the measure most sensitive to memory decline in cognitively healthy and MCI individuals [12, 33, 34]. The high correlation values reached between automatic and manual FACEmemory® scores (r = 0.98) confirmed the reliability of FACEmemory® automated scoring.

Since the S-FNAME was not recommended to be administered to individuals with MCI as it was too challenging for them [35], the FNAME-12 was created. This is a shortened version with more learning trials and a delayed recognition task [9]. Consistent with Papp et al.’s [9] findings, in which the paper-and-pencil FNAME-12 was highly correlated (r = 0.77) with the original S-FNAME (paper-and-pencil version with 16 faces), we found the computerized FACEmemory® scores were significantly correlated with the paper-and-pencil S-FNAME (r = 0.69), confirming that the computerized version is sensitive to complex associative memory, as expected. The reason the correlation values were not higher is because the original S-FNAME and FACEmemory® have some differences, such as the administration form (paper-and-pencil vs computerized), the number of faces (16 vs 12), and the target population (preclinical vs preclinical and prodromal AD). These findings parallel previous studies demonstrating that S-FNAME [4, 6, 7, 36] and its original paper-and-pencil short form, FNAME-12 [9], are complex and ecological tests sensitive to episodic memory. FACEmemory® also has ecological validity, given that associating names and occupations with new faces is an everyday event and at the same time, performing poorly at it is a common complaint among older adults [9].

Several studies have reported memory tests (e.g., the Free and Cued Reminding Test [37], the Word List from the Wechsler Memory Scale-III [23], the computerized CANTAB PAL [38], and CogState’s One Card Learning subtest [39, 40]) as valid tools for detecting MCI, a phenotype with an increased risk of conversion to dementia, mainly of the AD type [12, 13]. In this line, consistent with the paper-and-pencil FNAME-12 results [9], performances on the first self-administered verbal memory test, FACEmemory®, got worse from the CH to the naMCI to the aMCI groups, providing a useful gradation of impairment from normal aging to aMCI. Moreover, our results showed that FACEmemory® reached adequate sensitivity and specificity values to discriminate between CH and MCI subjects, mainly the aMCI. Thus, FACEmemory® may be a suitable test for detecting MCI, mainly the amnestic type. While a sensitivity of 80.5% and a specificity of 80% might not compare well to some other sensitivity/specificity metrics, FACEmemory® is still able to detect subtle cognitive changes, distinguishing between CH and MCI individuals.

A consistent path was observed throughout the study. The FACEmemory® scores of patients in the naMCI group were consistently better than those of the aMCI group and consistently worse than those of the CH group. While this can be seen as validation evidence that FACEmemory® primarily relies on episodic memory, it also implies that the test taps into other cognitive domains, such as executive functions. Several studies have reported that the correct learning and recall of face-name pairs require coordinated activity in a distributed memory network, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which are involved in encoding and retrieval of associative memories [41, 42].

Finally, lower scores on FACEmemory® were found to be related to higher evidence of CSF AD biomarkers. That is, total FACEmemory® scores were found to be significantly and inversely correlated with CSF Aβ42, mainly in the aMCI group, the group with the highest and most imminent risk of conversion to dementia [12, 13]. This result is consistent with those of other studies reporting a link between performances on episodic memory tests, such as the original FNAME [4], the S-FNAME [8], the PAL CANTAB [1], or the Ancient Farming Equipment Test [43], and biomarkers of AD pathology, either PET imaging or CSF. Moreover, our results are consistent with the findings showing that CSF tau levels are more related to cognitive functioning, mainly memory, than CSF Aβ levels [43,44,45,46,47,48]. Additionally, the Aβ/p-tau ratio, which includes both AD biomarkers, was the CSF measurement that best correlated with performance on FACEmemory®, reinforcing the hypothesis that this test is a diagnostic tool that reflects AD pathology changes [49].

Finally, the feasibility of FACEmemory® was supported by its capacity to obtain valid data from all the participants, including those with MCI. That is, all the participants completed the test and gave a favorable opinion of the tool, with a mean satisfaction score of 4.51 points (5 being the best judgment), independently of their diagnosis group. Most of them (96.7%) confirmed they would be willing to repeat the test in the future. Like those of studies involving other computerized tests, such as CogState [40], CANTAB [38], and C3-PAD [15], our results reinforce the fact that computerized tests are feasible, suitable, and valid in elderly populations, not only in clinical practice but also for clinical trials.

A limitation of this work is that it is a single-center study. Therefore, this design does not represent the general population. However, this is the first step. We expect that later on FACEmemory® will be extended to the rest of the Spanish-speaking population, fully self-administered, and translated into other languages, so that it can be administered to all out-patient clinics, particularly those in isolated areas with fewer resources. Further longitudinal studies will be needed to determine whether lower baseline scores on FACEmemory® are related to an increased risk of developing AD.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that the computerized memory test FACEmemory® may be a suitable test for detecting early cognitive impairment, mainly of the amnestic type. The test was well accepted by participants. Their test performance was found to worsen from normal aging to the naMCI to aMCI groups and was related to AD CSF biomarkers. A computerized test like this ensures standardized administration and scoring, and it might be a helpful memory prescreening tool.

Availability of data and materials

Data used can be requested through the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- Aβ42:

-

Amyloid beta 42

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- aMCI:

-

Amnestic mild cognitive impairment

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- ANOVA:

-

Univariate analysis of variance

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BDRS:

-

Blessed Dementia Rating Scale

- C3-PAD:

-

Computerized Cognitive Composite for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease

- CANTAB:

-

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery

- CDR:

-

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CH:

-

Cognitively healthy

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- FACEHBI:

-

Fundació ACE Healthy Brain Initiative

- FACEmemory®:

-

Computerized version of the Short Form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (by tablet). Copyright© 2017

- FNAME:

-

Face-Name Associative Memory Exam

- FNAME-12:

-

The short form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam

- FR:

-

Face recognition score

- GDPR:

-

General Data Protection Regulation

- LN1:

-

Names recalled in learning 1

- LN2:

-

Names recalled in learning 2

- LO1:

-

Occupations recalled in learning 1

- LO2:

-

Occupations recalled in learning 2

- LP:

-

Lumbar puncture

- NBACE:

-

Neuropsychological Battery of Fundació ACE

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- naMCI:

-

Non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment

- OHI:

-

Open House Initiative

- PAL:

-

Paired Associates Learning test

- p-tau:

-

Phosphorylated tau

- REN:

-

Names recognized

- REO:

-

Occupations recognized

- RLN:

-

Names in long-term recall

- RLO:

-

Occupations in long-term recall

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RSN:

-

Names in short recall

- RSO:

-

Occupations in short recall

- S-FNAME:

-

Spanish version of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- t-tau:

-

Total tau

References

Nathan PJ, Lim YY, Abbott R, Galluzzi S, Marizzoni M, Babiloni C, et al. Association between CSF biomarkers, hippocampal volume and cognitive function in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Neurobiol Aging. 2017;53:1–10.

Werheid K, Clare L. Are faces special in Alzheimer’s disease? Cognitive conceptualisation, neural correlates, and diagnostic relevance of impaired memory for faces and names. Cortex. 2007;43:898–906.

Mangels JA, Manzi A, Summerfield C. The first does the work, but the third time’s the charm: the effects of massed repetition on episodic encoding of multimodal face–name associations. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;22:457–73.

Rentz DM, Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Frey M, Olson LE, Frishe K, et al. Face-name associative memory performance is related to amyloid burden in normal elderly. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2776–83.

Amariglio RE, Frishe K, Olson LE, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sperling RA, et al. Validation of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam in cognitively normal older individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:580–7.

Alegret M, Valero S, Ortega G, Espinosa A, Sanabria A, Hernández I, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam (S-FNAME) in cognitively normal older individuals. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30:712–20.

Alegret M, Rodríguez O, Espinosa A, Ortega G, Sanabria A, Valero S, et al. Concordance between subjective and objective memory impairment in volunteer subjects. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48:1109–17.

Sanabria A, Alegret M, Rodriguez-Gomez O, Valero S, Sotolongo-Grau O, Monté-Rubio G, et al. The Spanish version of Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (S-FNAME) performance is related to amyloid burden in subjective cognitive decline. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3828.

Papp KV, Amariglio RE, Dekhtyar M, Roy K, Wigman S, Bamfo R, et al. Development of a psychometrically equivalent short form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam for use along the early Alzheimer’s disease trajectory. Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;28:771–85.

Vila-Castelar C, Papp KV, Amariglio RE, Torres VL, Baena A, Gomez D, et al. Validation of the Latin American Spanish version of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam in a Colombian sample. Clin Neuropsychol. 2019;0:1–12.

Kormas C, Megalokonomou A, Zalonis I, Evdokimidis I, Kapaki E, Potagas C. Development of the Greek version of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam (GR-FNAME12) in cognitively normal elderly individuals. Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;4046:1–12.

Espinosa A, Alegret M, Valero S, Vinyes-Junqué G, Hernández I, Mauleón A, et al. A longitudinal follow-up of 550 mild cognitive impairment patients: evidence for large conversion to dementia rates and detection of major risk factors involved. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:769–80.

Oltra-Cucarella J, Ferrer-Cascales R, Alegret M, Gasparini R, Díaz-Ortiz LM, Ríos R, et al. Risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease for different neuropsychological mild cognitive impairment subtypes: a hierarchical meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Aging. 2018;33:1007–21.

Bauer RM, Iverson GL, Cernich AN, Binder LM, Ruff RM, Naugle RI. Computerized neuropsychological assessment devices: joint position paper of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology and the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;27:362–73.

Rentz DM, Dekhtyar M, Sherman J, Burnham S, Blacker D, Aghjayan SL, et al. The feasibility of At-Home iPad Cognitive Testing for use in clinical trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3:8–12.

Égerházi A, Berecz R, Bartók E, Degrell I. Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:746–51.

Boada M, Tárraga L, Hernández I, Valero S, Alegret M, Ruiz A, et al. Design of a comprehensive Alzheimer’s disease clinic and research center in Spain to meet critical patient and family needs. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2014;10:409–15.

Alegret M, Espinosa A, Valero S, Vinyes-Junqué G, Ruiz A, Hernández I, et al. Cut-off Scores of a Brief Neuropsychological Battery (NBACE) for Spanish individual adults older than 44 years old. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8.

Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114:797–811.

Aguilar M, Santacruz P, Insa R, Pujol A, Sol JM, Blesa R, et al. Normalización de instrumentos cognitivos y funcionales para la evaluación de la demencia (NORMACODEM) (I): objetivos, contenidos y población. Neurologia. 1997;12:61–8.

Rodriguez-Gomez O, Sanabria A, Perez-Cordon A, Sanchez-Ruiz D, Abdelnour C, Valero S, et al. FACEHBI: a prospective study of risk factors, biomarkers and cognition in a cohort of individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Study rationale and research protocols. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;4:100–8.

Abdelnour C, Rodríguez-Gómez O, Alegret M, Valero S, Moreno-Grau S, Sanabria Á, et al. Impact of recruitment methods in subjective cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:625–32.

Alegret M, Espinosa A, Vinyes-Junqué G, Valero S, Hernández I, Tárraga L, et al. Normative data of a brief neuropsychological battery for Spanish individuals older than 49. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:209–19.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. A practical state method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Blesa R, Pujol M, Aguilar M, Santacruz P, Bertran-Serra I, Hernández G, et al. Clinical validity of the “mini-mental state” for Spanish speaking communities. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:1150–7.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 2012;43:2412.

Petersen R. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2004;62:1160–3.

Vanderstichele H, Bibl M, Engelborghs S, Le Bastard N, Lewczuk P, Molinuevo JL, et al. Standardization of preanalytical aspects of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: a consensus paper from the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:65–73.

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Carrillo MC, Collins S, Chalbot S, et al. CSF biomarker variability in the Alzheimer’s Association Quality Control Program on behalf of the Alzheimer’s Association QC Program Work Group. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:251–61.

Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–800.

Wild K, Howieson D, Webbe F, Seelye A, Kaye J. Status of computerized cognitive testing in aging: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:428–37.

Schatz P, Browndyke J. Applications of computer-based neuropsychological assessment. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002;17:395–410.

Sahakian BJ, Morris RG, Evenden JL, Heald A, Levy R, Philpot M, et al. A comparative study of visuospatial memory and learning in Alzheimer-type dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:695–718.

Raymond PD, Hinton-Bayre AD, Radel M, Ray MJ, Marsh NA. Test-retest norms and reliable change indices for the MicroCog Battery in a healthy community population over 50 years of age. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:261–70.

Rubiño J, Andrés P. The Face-Name Associative Memory test as a tool for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1–5.

Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sullivan C, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:2880–6.

Grober E, Veroff AE, Lipton RB. Temporal unfolding of declining episodic memory on the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test in the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s disease: implications for clinical trials. Alzheimers Dementia. 2018;10:161–71.

Junkkila J, Oja S, Laine M, Karrasch M. Applicability of the CANTAB-PAL computerized memory test in identifying amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34:83–9.

Rabin LA, Smart CM, Crane PK, Amariglio RE, Berman LM, Boada M, et al. Subjective cognitive decline in older adults: an overview of self-report measures used across 19 international research studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48:S63–86.

Mielke MM, Machulda MM, Hagen CE, Edwards KK, Roberts RO, Pankratz VS, et al. Performance of the CogState computerized battery in the Mayo Clinic Study on Aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1367–76.

Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7709–17.

Vannini P, O’Brien J, O’Keefe K, Pihlajamaki M, Laviolette P, Sperling RA. What goes down must come up: role of the posteromedial cortices in encoding and retrieval. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:22–34.

Tort-Merino A, Valech N, Peñaloza C, Grönholm-Nyman P, León M, Olives J, et al. Early detection of learning difficulties when confronted with novel information in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease stage 1. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:855–70.

Rolstad S, Berg AI, Bjerke M, Johansson B, Zetterberg H, Wallin A. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers mirror rate of cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:949–56.

Hessen E, Nordlund A, Stalhammar J, Eckerström M, Bjerke M, Eckerström C, et al. T-tau is associated with objective memory decline over two years in persons seeking help for subjective cognitive decline: a report from the Gothenburg-Oslo MCI Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:619–28.

Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:362–81.

Glodzik L, de Santi S, Tsui WH, Mosconi L, Zinkowski R, Pirraglia E, et al. Phosphorylated tau 231, memory decline and medial temporal atrophy in normal elders. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2131–41.

Tort-Merino A, Olives J, Leon M, Penaloza C, Valech N, Santos-Santos MA, et al. Tau protein is associated with longitudinal memory decline in cognitively healthy subjects with normal Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker levels. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70:211–25.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Budd Haeberlein S, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease HHS Public Access Author manuscript. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all individuals who participated in the present study; without their collaboration, this work would not have been possible. Fundació ACE is a member of Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades.

We also want to thank Raul Espinosa for his support and persistence in finding a way to automate the tool; Tanya Valero, Gemma Boada, and Xavier Manrubia from Editorial Glosa; Mercedes Pageo from IECISA; Pau Plana from 3&Punt Solucions Informàtiques; the sponsors for making this project possible; and all the participating investigators and personnel from Fundació ACE for their close collaboration and continuous intellectual input. We would like to extend our gratitude to the sponsors supporting the FACEHBI project (Grifols SA, Life Molecular Imaging GmbH, Laboratorios Echevarne, Araclon Biotech, Laboratorios Echevarne S.A. and Fundació ACE) and all the FACEHBI study group: Abdelnour C1,2, Aguilera N1, Alarcón-Martín E1, Alegret M1,2, Berthier M8, Boada M1,2, Buendia M1, Bullich S3, Campos F4, Cañabate P1,2, Cañada L1, Cuevas C1, de Rojas I1, Diego S1, Espinosa A1,2, Esteban-De Antonio E1, Gailhajenet A1, García P1, Gil S1, Giménez J5, Gismondi R3, Gómez-Chiari M5, Guitart M1, Hernández I1,2, Ibarria, M1, Lafuente A1, Lomeña F4, López-Cuevas R1, Marquié M1,2, Martín E1, Martínez J1, Mauleón A1, Moreno M1, Moreno-Grau S1,2, Montrreal L1, Nogales AB1, Núñez L6, Orellana A1, Ortega G1, Páez A6, Pancho A1, Pelejà E1, Pérez-Cordon A1, Pérez-Grijalba V7, Pesini P7, Preckler S1, Roberto N1, Rodríguez-Gómez O1,2, Romero J7, Ramis MI1, Rosende-Roca M1, Ruiz A1,2, Sanabria A1,2, Sarasa M7, Sánchez, D1, Sotolongo-Grau O1, Tartari JP1, Tárraga L1,2, Tejero MA5, Torres M6, Valero S1,2, Vargas L1, Vivas A5.

1Fundació ACE, Alzheimer Treatment and Research Center, Barcelona, Spain

2CIBERNED, Center for Networked Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases, National Institute of Health Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain

3Life Molecular Imaging GmbH, Berlin, Germany

4Servei de Medicina Nuclear, Hospital Clínic I Provincial, Barcelona, Spain;

5Departament de Diagnòstic per la Imatge, Clínica Corachan, Barcelona, Spain

6Grifols®

7Araclon Biothech®, Zaragoza, Spain;

8Cognitive Neurology and Aphasia Unit (UNCA), University of Malaga

The FACEmemory® is copyrighted by Fundació ACE and is made freely available for non-commercial purposes.

Funding

This work was funded by the research funds of Fundació ACE, Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, and was partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Health (FIS PI17/01474) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain) (BIOFACE project) and the sponsors supporting the FACEHBI project (Grifols SA, Life Molecular Imaging GmbH, Laboratorios Echevarne, Araclon Biotech, Laboratorios Echevarne S.A. and Fundació ACE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and design of study were done by MA, MB, SV, DMR, KVP, AR, and LT. Analysis and interpretation of the data were done by MA, SV, MB, and DMR. Analysis of the CSF biomarkers was done by AO and AR. Enrollment and assessment of patients in Fundació ACE were done by MA, NM, NR, SG, MM, IH, CR, AS, AP, AE, GO, AM, CA, and MR. Critical review of the manuscript and approval of the final version were done by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to the evaluation, written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Spanish biomedical laws (Law 14/2007, July 3, about biomedical research; Royal Decree 1716/2011, November 18). The study was approved by the Fundació ACE Research Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alegret, M., Muñoz, N., Roberto, N. et al. A computerized version of the Short Form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FACEmemory®) for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res Therapy 12, 25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00594-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00594-6