Abstract

Objectives

Noma is a facially disfiguring disease that affects the oral cavity and midface structures. If left untreated, the disease is fatal. Noma causes severe cosmetic and functional defects in survivors, leading to psychiatric and social problems. However, there are limited data on psychosocial and functional sequelae associated with this disease. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate psychosocial and functional morbidity among facially disfigured untreated Noma cases. Study participants were volunteer patients diagnosed with noma and awaiting surgery at two noma treatment centers in Ethiopia. A questionnaire derived from the APA’s DSM-5, the DAS59, and the Appearance Anxiety Inventory protocol was used to measure the psychosocial and functional morbidity of the cases between September 16 and October 10, 2022.

Results

A total of 32 noma cases (19 women and 13 men) awaiting the next surgical campaigns were involved in the study. Study participants reported severe social (Likert score = 2.8) and psychological (Likert score = 3.0) morbidity. Functional limitation was moderate (Likert score = 2.9). This study has shown that psychosocial and functional morbidity in untreated noma cases in Ethiopia is substantial. Therefore, policymakers, clinicians, and researchers need to pay sufficient attention to providing adequate health care and preventing the occurrence of the disease in the long term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

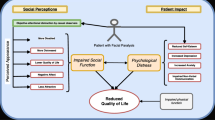

Noma is a progressive and fatal disease (85–90% death rate) that exclusively affects the poor. The disease is rare in developed countries but is still not uncommon in many developing countries, especially in the noma belt region, which stretches from the west (Senegal) to the east (Ethiopia) of Africa. Noma is a devastating orofacial gangrene that affects the orofacial anatomic region and leaves victims with short- and long-term functional, aesthetic, and related psychosocial impairments [1, 2]. Facial disfigurement has long been considered one of the most potentially distressing aspects of human anatomy, as the facial region is critical to self-concept, interpersonal relationships, and communication. A growing body of literature also notes that people with facial disfigurements have difficulty adjusting to their condition and experience social difficulties. Said that Noma-related abnormalities including skin induration, limited movement of the temporomandibular joints, and muscle involvement leading to progressive limitation of orofacial range of motion, results in overall psychosocial and functional (speech and mastication) morbidity among disease survivors [3, 4].

Although there is a growing body of literature on the psychosocial aspects of various facial disfigurements, little is known about Noma and its psychosocial impacts on the patient’s life. In this regard, only a few studies have shown that noma is associated with significant psychosocial and functional morbidity [5, 6]. This study was primarily initiated to investigate the psychosocial and functional morbidity among facially disfigured untreated Noma cases in Ethiopia. Filling the knowledge gap and providing sound scientific evidence to concerned bodies including policymakers, clinicians, and researchers were the other objectives of the study.

Methods

A single-point cross-sectional study of noma patients awaiting facial reconstruction as part of the Facing Africa and Harar projects examined the disease’s psychosocial, functional, and aesthetic impact between September 16 and October 10, 2022. Volunteer patients who were 18 years old and above at the time of data collection and those with no history of Noma-related surgical intervention were considered for data analysis.

Instruments

A questionnaire derived from the APA’s DSM-5 severity measure for social anxiety disorder (social phobia), the DAS59, and the Appearance Anxiety Inventory protocol was used to measure the psychological and social morbidity of the subjects. The questionnaire included 24 questions and contained demographic and clinical data. Of these, 10, 4, and 10 questions were designed to measure psychological, functional, and social outcomes, respectively. The questions were formulated based on Linker’s scales for measuring psychological and functional impairment, which were aligned with the core objectives of the study. 5- and 4-point Likert scales were used to scale the responses of study respondents.

A numerical analysis of the Linkert scale was performed to derive a numerical value (domain mood score) that quantifies and describes the cumulative response of the study participants in each domain (psychological, social, or functional) studied. Item sentiment scores were calculated for each question in the questionnaire before the corresponding domain sentiment scores were determined. Each item of the measure was scored on a 5-point scale (0 = never; 1 = occasionally; 2 = sometimes; 3 = most of the time; and 4 = all of the time). Similarly, item and domain scores (psychological and social) were also reduced to a 5-point scale, which allows the researcher to describe the severity of psychological and social morbidity among noma cases in terms of “none” (0), “mild” (1), “moderate” (2), “severe” (3), or “extreme” (4).

On the other hand, functional morbidity was assessed using Linker’s 4-point scale to measure the problem level. In this case, each item of the measurement scale was rated on a 4-point scale (1 - no problem at all, 2 - a minor problem, 3 - moderate problem, and 4 - severe problem). The same scales were used to describe item and functional area sentiment scores.

In addition, the item sentiment scores were calculated for each question of the questionnaire. First, the numerical value of each sentiment score was multiplied by the number of corresponding respondents for that item/question. Then, the sum of these scores was divided by the total number of study participants to calculate the sentiment score for each item. The same principle was used to calculate the sentiment scores for each domain.

The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were ascertained by conducting a pilot survey before applying it to collect the final data for analysis. The study participants were interviewed individually by the data collector (the principal researcher).

Data analysis

The IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Statistics, version 29 version was used to analyze the collected data. Descriptive statistical analysis was applied to describe and present the findings of the study in simple and compact forms.

Results

A total of 32 volunteer and accessible patients who were on the waiting list for future surgery under the Facing Africa and Harar projects between September 16 and October 10, 2022, were included in the study. Eighteen (56.3%) were female and 14 (43.7%) were male. The age of the study participants ranged from 20 to 61 years. After data analysis, it was found that the study participants reported severe social (Likert score = 2.8) and psychological (Likert score = 3.0) morbidity. Functional limitation was classified as moderate (Likert score = 2.9). Compared to males (9 out of 14), proportionally more females (15 out of 18) reported severe forms of social and psychological morbidity.

Findings related to social morbidity (appearance anxiety)

As shown in Table 1, the study participants’ social morbidity was severe (Linkert score = 2.8). The detailed psychosocial morbidity associated with noma is described in the following table.

Table 1 shows the noma-related social morbidity in detail. The items and domain sentiment levels are shown with the calculated corresponding numerical values. The domain sentiment level value describes the overall social morbidity among the study participants.

Findings related to psychological morbidity (social phobia)

Detailed results related to noma-induced psychological morbidity are described in Table 2. Study participants generally had severe psychological morbidity or social anxiety disorder (Linkert score = 3.0).

Table 2 illustrates the noma-associated psychological morbidity (social phobia). The domains’ items and sentiment levels are presented with the corresponding numerical values. The score for the sentiment domain shows the overall psychological morbidity of noma cases in Ethiopia.

Findings related to functional morbidity

Results related to noma-induced functional morbidity are shown in Table 3. Noma-induced functional limitation was calculated to be moderate overall (linker score = 2.9) in those who reported at least one of the four functional impairments measured in the study.

Table 3 shows the noma-associated functional morbidity in detail. The domains’ items and sentiment levels are shown with the corresponding numerical values. The score for the sentiment level of the domain shows the overall functional morbidity of the study subjects.

Discussion

With an estimated annual incidence of 140,000 cases worldwide, noma is a disease that poses enormous challenges to survivors due to its physical, psychological, and social impact [7]. Reports indicate that people with craniofacial disease are at known risk for several psychosocial problems, including low self-esteem, learning and language problems, depression, anxiety, and negative social reactions from peers [8,9,10,11]. When considering the psychosocial impact of noma, it is important to understand several elements of the disease [12]. The disfiguring facial changes caused by noma can directly impact mental and social health [13]. Similarly, the physical aspects of the disease, such as the altered ability to open the mouth, slurred speech, and excessive drooling, may affect social and psychological functioning as a secondary phenomenon by interfering with daily life [14,15,16,17]. According to studies, Noma is reportedly associated with long-term functional, aesthetic, and psychosocial impairments [16, 17]. Still, the impact of Noma on the psychosocial aspect of patients’ life is not well investigated. It is undeniable that certain psychological, social, and functional consequences of noma have been reported in the literature. However, these data are reported by few and mainly retrospective studies [6]. For example, noma survivors in Laos reported high levels of hopelessness and associated functional impairments [18]. Study participants who took part in this study also reported significant functional impairments (Likert score = 2.9). In Nigeria, a 37% psychiatric morbidity prevalence rate was found in noma cases with disfigured faces [14]. Similarly, the results of this study revealed severe noma-related social (Likert score = 2.8) and psychological morbidity (Likert score = 2.51).

In the present study, the functional, social, and psychological aspects of noma were found significant determinants of the study participants’ quality of life (QOL). The present study suggests that psychosocial morbidity is high in patients who are facially disfigured by Noma. The results also showed that the study participants were highly anxious because of their poor appearance and extremely dissatisfied with their facial expressions. Arguably, this dissatisfaction with facial expressions may lead to life-threatening behavioral problems. Given these risks, regular assessments of the psychosocial needs of people with noma must be emphasized. In addition, policymakers and experts need to be attentive in formulating a workable prevention strategy.

Limitations

There was a language barrier between the investigator and two study participants, so a translator had to be consulted. The translator may not have translated the responses of these study participants correctly, as not everything that exists in a particular language community can be accurately translated into another language. This could have a slight impact on the results of the study.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Feller L, Lemmer J, Khammissa RAG. Is Noma a neglected/overlooked tropical disease? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116(10):884–8.

Gebretsadik HG, de Kiev LC. A retrospective clinical, multi-center cross-sectional study to assess the severity and sequela of Noma/Cancrum oris in Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(9):e0010372.

Bisseling P, Bruhn J, Erdsach T, Ettema AM, Sautter R, Bergé SJ. Long-term results of trismus release in noma patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(9):873–7.

Versnel SL, Plomp RG, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mathijssen IMJ. Long-term psychological functioning of adults with severe congenital facial disfigurement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(1):110–7.

Kagoné M, Mpinga EK, Dupuis M, Moussa-Pham MSA, Srour ML, Grema MSM, et al. Noma: experiences of survivors, Opinion leaders and Healthcare Professionals in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(7):142.

Gebretsadik HG, Psychosocial. Functional and aesthetic-related patients’ reported Outcomes Measures (PROMS) after Orofacial reconstructive surgery among Noma cases in Ethiopia. Int J Sch Cogn Psycho. 2022;9:274.

Oginni FO, Oginni AO, Ugboko VI, Otuyemi OD. A survey of cases of cancrum oris seen in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1999;9(2):75–80.

ElHawary H, Salimi A, Gilardino MS. Ethics of Facial Transplantation: the Effect of Psychological Trauma Associated with Facial Disfigurement on Risk Acceptance and decision making. Ann Surg. 2022;275(5):1013–7.

Versnel SL, Duivenvoorden HJ, Passchier J, Mathijssen IMJ. Satisfaction with facial appearance and its determinants in adults with severe congenital facial disfigurement: a case-referent study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS. 2010;63(10):1642–9.

Van den Elzen MEP, Versnel SL, Hovius SER, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mathijssen IMJ. Adults with congenital or acquired facial disfigurement: impact of appearance on social functioning. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2012;40(8):777–82.

Sarwer DB, Bartlett SP, Whitaker LA, Paige KT, Pertschuk MJ, Wadden TA. Adult psychological functioning of individuals born with craniofacial anomalies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(2):412–8.

Srour ML, Marck K, Baratti-Mayer D, Noma. Overview of a neglected disease and human rights violation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(2):268–74.

Srour ML, Watt B, Phengdy B, Khansoulivong K, Harris J, Bennett C, Strobel M, Dupuis C, Newton PN. Noma in Laos: stigma of severe poverty in rural Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78(4):539–42.

Feller L, Altini M, Chandran R, Khammissa R, a. G, Masipa JN, Mohamed A, et al. Noma (cancrum oris) in the south african context. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol. 2014;43(1):1–6.

Yunusa M, Obembe A. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and its associated factors among patients facially disfigured by cancrum oris in Nigeria a controlled study. Niger J Med. 2012 Jul-Sep;21(3):277–81.

Mpinga EK, Srour ML, Moussa MA, Dupuis M, Kagoné M, Grema MSM, Zacharie NB, Baratti-Mayer D. Economic and social costs of Noma: design and application of an estimation model to Niger and Burkina Faso. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(7):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7070119.

Wali IM, Regmi K. People living with facial disfigurement after having had noma disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(10):1243–55.

Srour ML. Elise Farley, & Emmanuel Kabengele Mpinga. Lao Noma Survivors: a Case Series, 2002–2020. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;106(4):1269–74. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-1079.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest appreciation to Yenigat Abera (Ethiopian Country Manager; Facing Africa) for her extensive assistance during the data collection phase of this project.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G.G. conceptualized the research idea, collected the needed data, analyzed the collected data, wrote the first draft of the paper, reviewed and validated the paper, and wrote the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Addis Ababa Health Bureau Institutional Review Board (IRB) Ethics Committee approved this study. The approval number of the clearance statement is “A/A/H/B/2116/227.“ The medical information was kept confidential. In addition, the researcher used the patients’ initials in the questionnaire and excel sheet. Formal written informed consent was also obtained from the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebretsadik, H.G. The severity of psychosocial and functional morbidity among facially disfigured untreated noma cases in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 16, 162 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06440-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06440-w