Abstract

Background

The current study reports dissemination of highly stable bla OXA-10 family of beta lactamases among diverse group of nosocomial isolates of Gram-negative bacilli within a tertiary referral hospital of the northern part of India.

Methods

In the current study, a total number of 590 Gram negative isolates were selected for a period of 1 year (i.e. 1st November 2011–31st October 2012). Members of Enterobacteriaceae and non fermenting Gram negative rods were obtained from Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Silchar, India. Screening and molecular characterization of β-lactamase genes was done. Integrase gene PCR was performed for detection and characterization of integrons and cassette PCR was performed for study of the variable regions of integron gene cassettes carrying bla OXA-10. Gene transferability, stability and replicon typing was also carried out. Isolates were typed by ERIC as well as REP PCR.

Results

Twenty-four isolates of Gram-negative bacilli that were harboring bla OXA-10 family (OXA-14, and OXA16) with fact that resistance was to the extended cephalosporins. The resistance determinant was located within class I integron in five diverse genetic contexts and horizontally transferable in Enterobacteriaceae, was carried through IncY type plasmid. MIC values were above break point for all the tested cephalosporins. Furthermore, co-carriage of bla CMY-2 was also observed.

Conclusion

Multiple genetic environment of bla OXA-10 in this geographical region must be investigated to prevent dissemination of these gene cassettes within bacterial population within hospital settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Expansion of β-lactamases in Gram-negative rods has been documented as most severe threat to the management of infectious diseases [1–4]. The ever-increasing use of antibiotics with the evolution of intrinsic and acquired resistance has led to the development of resistance mechanism in Gram-negative rods contributing to the expansion of several multi-drug resistance epidemics in hospital environment [1, 3, 5]. OXA-10 type was known to have narrow spectrum β-lactamase activity; although variant of this enzyme family has expanded-spectrum activity [3, 6, 7]. It has been extensively associated with infection of Gram-negative bacteria in the last two decades restricting therapeutic options. These genes are often reported to be located within integron gene cassettes [3, 4]. However, these rare types of beta lactamases are often unreported in the light of current incidence of New Delhi metallo beta lactamase and CTX-M types. The current study reports the dissemination of highly stable bla OXA-10 family among diverse group of nosocomial isolates of Gram-negative bacilli within a tertiary referral hospital of the northern part of India.

Methods

Sample size

A total number of 590 consecutive, non duplicate, Gram-negative rods consisting members of Enterobacteriaceae family (Escherichia coli, n = 208; Klebsiella spp., n = 99; Proteus spp., n = 28) and non fermenting Gram-negative rods (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, n = 241; Acinetobacter baumannii, n = 14) were collected from different clinical specimens spanning a period of 1 year (November 2011–October 2012) from Silchar Medical College and Hospital, India (Table 1).

Screening and molecular characterization of β-lactamases

Isolates resistant to at least one of the expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, or ceftriaxone) were selected for the study. For amplification and characterization of β-lactamase genes, multiplex PCR was performed (T100, BioRad-USA) with set of five primers namely: bla CTX-M [8], bla TEM, bla OXA-10, bla OXA-2 [9] and bla SHV [10] (Additional file 1: Table S1). Previously confirmed beta-lactamase genes were used as positive control which were obtained from Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. PCR was performed by using Go-Taq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, USA) and products were visualized in 0.5% Agarose gel. PCR product was purified using Gene JET PCR product purification kit (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania) and sequencing was done using Sanger’s Method in Xcelris Lab Pvt Ltd in Ahmedabad, India.

PCR assay was also carried out for detection of AmpC genes in donor strains and transformants as described earlier [11]. Carbapenemase production in donor strains and transformants was tested by modified Hodge test, Imipenem-EDTA disc test [12] and boronic acid inhibition test [13] followed by PCR assay targeting bla OXA-48 [14] and bla OXA-23, -24/40 and -58 [15].

Study of genetic context and southern blot hybridization

Presence of integron was detected by integrase gene PCR [16]. To study the variable regions of integron gene cassettes carrying bla OXA-10, two PCR assays were performed consequently: in one reaction 5′-CS and reverse primer of bla OXA-10 and in other reaction 3′-CS and forward primer of bla OXA-10 were used [9, 16] (Additional file 1: Table S2). Purified PCR products were cloned on pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, USA) and further sequenced. To validate our study, Southern hybridization was performed on agarose gel by in-gel hybridization with the bla OXA-10 family specific probe labeled with Dig High Prime Labeling Mix (Roche, Germany) detection Kit. Plasmid DNA was separated on agarose gel and transferred to nylon membrane (Hybond N, Amersham, UK) and hybridized.

Transferability, PCR-based replicon typing and stability of bla OXA-10 family

Transformation was carried out using E. coli JM107 as recipient. Conjugation experiment was performed taking clinical isolates as donors and a streptomycin resistant E. coli-strain B (Genei, Bangalore) as recipient and transconjugants were selected on Luria–Bertani Agar plates containing cefotaxime (0.5 µg/ml) and streptomycin (800 µg/ml). Plasmid transfer was confirmed by colony PCR of transconjugants and transformants with the targeted primers [8, 9]. Plasmid stability of all bla OXA-10 producers as well as their transformants was analyzed by serial passages method for consecutive 115 days without antibiotic pressure [17]. Colony PCR assay was carried out in the isolates after each passage. Incompatibility typing was carried out by PCR-based replicon typing targeting 18 different replicon types [18] among all the wild types and their transformants carrying bla OXA-10.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and minimum inhibitory concentration determination

Antimicrobial susceptibility of bla OXA-10-harboring donor strains as well as transformants was determined by Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method towards all non-β-lactam antibiotics (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India) [19]. MICs of donor as well as transformants and transconjugants were also done against beta lactam groups on Muller Hinton agar (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India) plates by agar dilution method and results were interpreted as per CLSI recommendation [19].

Strain typing

Typing of all bla OXA-10 harboring isolates was done by Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) and repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP) PCR [20].

Results and discussion

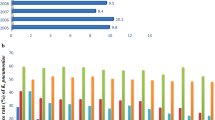

A total of 58.5% (n = 345) isolates were resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Among them 24 showed amplification with bla OXA-10 primers and were further confirmed by sequencing as OXA-14 (n = 15), and OXA-16 (n = 9) derivatives (Table 1). Sequencing results confirmed the presence of resistance determinant within class I integron with five different types of genetic environment (Fig. 1; Table 1). Upstream region of bla OXA-10 was occupied by dfrA12 (Type 1), dfrA17 (Type 5), dfrA1 (Type 3 and Type 2), dfrA7 (Type 4), arr2 (Type 2), aac A4 (Type 2), aad A5 (Type 4 and Type 5), while in downstream regions aad A2 (Type 1), aad A1 (Type 2 and Type 3), aac (6′)1b (Type 4), and qacE (Types 1–5) genes were present (Fig. 1). Plasmid encoding bla OXA-10 was successfully transferred in E. coli for Enterobacteriaceae, while in case of P. aeruginosa the attempt was not successful. Hybridization experiment revealed that bla OXA-10 carriage was plasmid mediated for Enterobacteriaceae. Replicon typing result established that bla OXA-10 was encoded within IncY type plasmid (Table 1) (Additional file 2: Figure S1). All isolates belonging Enterobacteriaceae family were found susceptible to tigecycline while Polymyxin B susceptibility was observed in P. aeruginosa. In case of Enterobacteriaceae, MICs of donor strain and transformants were observed above the breakpoint against cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams (Table 2) and similar MIC pattern was too observed in P. aeruginosa (Table 3). The bla OXA-10 was highly stable and none of the isolates lost the gene till 115 serial passages. Modified Hodge test could detect carbapenemase activity in seven isolates and bla CMY-2 was also co-carried along with bla OXA-10 in four isolates (Table 1). DNA fingerprinting by ERIC (in E. coli—ERIC Types 1–9; Klebsiella spp.—ERIC Types 1–3; Proteus spp.—ERIC Type 1) (Table 1; Additional file 2: Figure S2) and REP PCR (In P. aeruginosa- REP Types 1–11) (Table 1; Additional file 2: Figure S3) was suggestive that diverse clonal types were present.

So far, in India predominant types of beta-lactamases are CTX-M-15 and in recent years carbapenem therapy is compromised due to emergence of New Delhi Metallo beta-lactamase from this subcontinent. However, OXA type beta lactamases with extended spectrum activities are rarely reported [21, 22]. Our data showed that the majority of the isolates were recovered from surgery ward (37.5%; n = 9) followed by medicine (33.33%; n = 8), pediatrics (16.66%; n = 4), and gynecology (12.5%; n = 3). Carriage of bla OXA-10 within integron with diverse genetic environment comprising different coexisting-resistant determinant shows its multiple sources of acquisition and complicacy while determining the therapeutic options. It was also found that bla OXA-10 was horizontally transferable in Enterobacteriaceae family which was supported by transformation and conjugation. However, unsuccessful transfer of bla OXA-10 in P. aeruginosa could be due to their plasmid not being replicated within E. coli recipient or a chromosomal location of the gene. High MIC against carbapenems could be due to presence of some gene types which was not amplified by our target primers. Capability of the organisms to retain the resistant gene even after withdrawal of antibiotic pressure underscores their vertical transfer and persistence in the cell, which possibly can be the reason of expansion of this resistance determinant within hospital environment as well as in community. High MICs of the donor strain as well as their transformants could be due to the coexistence of another β-lactamase enzyme as observed in the current study.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of gene cassette-mediated carriage of bla OXA-10 from India. Their acquisition and dissemination as well as adaptation against high antibiotic pressure in the hospital environment demands immediate measure to prevent transmission of these genetic vehicles, by the adoption of proper infection control measures and treatment policies.

Abbreviations

- ERIC:

-

enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus

- REP:

-

repetitive extragenic palindromic

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- bla :

-

beta-lactamase

- Inc:

-

incompatibility

- MIC:

-

minimum inhibitory concentration

- EDTA:

-

ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid

- CLSI:

-

Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute

References

Chaudhary M, Payasi A. Prevalence, genotyping of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates for Oxacillinase resistance and mapping susceptibility behaviour. J Microb Biochem Technol. 2014;6:063–7.

Chaudhary M, Payasi A. Rising antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from clinical specimens in India. J Proteom Bioinform. 2013;6:005–9.

Poirel L, Nass T, Nordmann P. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:24–38.

Rasmussen JW, Hoiby N. OXA-type carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:373–83.

Chaudhary M, Payasi A. Prospective study for antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolated from various clinical specimens in India. J Microb Biochem Technol. 2012;4:157–60.

Bradford PA. Extended spectrum β-lactamases in 21st century: characterization, epidemiology and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:933–51.

Naas T, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Minor extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:42–52.

Lee S, Park YJ, Kim M, Lee HK, Han K, Kang CS. Prevalence of Ambler class A and D β-lactamases among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:122–7.

Bert F, Branger C, Zechovsky NL. Identification of PSE and OXA β-lactamase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:11–8.

Colom K, Perez J, Alonso R, Aranguiz AF, Larino E, Cisterna R. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for detection of bla TEM, bla SHV and bla OXA-1 genes in Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;223:147–51.

Dallenne C, Costa AD, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:490–5.

Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, Walsh TR. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, bla NDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5046–54.

Pournaras S, Poulou A, Tsakris A. Inhibitor-based methods for the detection of KPC carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in clinical practice by using boronic acid compounds. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1319–21.

Shibl A, Al-Agamy M, Memish Z, Senok A, Khader SA, Assiri A. The emergence of OXA-48 and NDM-1-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:1130–3.

Mendes RE, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Castanheira M, Jones RN. Emergence and widespread dissemination of OXA-23, -24/40 and -58 carbapenemases among Acinetobacter spp. in Asia-Pacific nations: report from the SENTRY Surveillance Program. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:55–9.

Koeleman JGM, Stoof J, Van Der Bijl MW, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Savelkoul PH. Identification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii by integrase gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:8–13.

Locke JB, Rahawi S, LaMarre J, Mankin LS, Shawa KJ. Genetic environment and stability of cfr in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CM05. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:332–40.

Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63:219–28.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-first informational supplement. M100-S21. Wayne: CLSI; 2011.

Versalovic J, Schneider M, Bruijn FJ, Lupski JR. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:25–40.

Maurya AP, Talukdar AD, Chanda DD, Chakravarty A, Bhattacharjee A. Genetic environment of OXA-2 β-lactamase producing Gram negative bacilli from a tertiary referral hospital of India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:368–9.

Bhattacharjee A, Sen MR, Anupurba S, Prakash P, Nath G. Detection of OXA-2 group extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:703–4.

Authors’ contributions

APM: Design and performed the experimental work, literature search, data collection, analysis and prepared the manuscript. DD: Participated in experiment designing, supervision and manuscript correction. MKB: Involved in experimental works and sample collection and analysis of data. DP: Participated in conception and designing study and analysis of data. BI: Participated in experiments and analysis of data and manuscript preparation. DC: Participated in experimental designing, manuscript preparation and data analysis. ADT: Participated in drafting the manuscript. AC: Participated in experiment designing, sample collection and manuscript correction. SM: Involved in experimental work data analysis and manuscript preparation. AB: Supervised the research work and participated in designing the study and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Head of Department, Microbiology, Assam University for providing infrastructure. They would also like to acknowledge the help from Assam University Biotech Hub for providing laboratory facility to complete this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to publish

All the participants have given their consent to publish the finding of this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The work was approved by Institutional Ethical committee of Assam University, Silchar vide reference number: IEC/AUS/2013-002. The authors confirm that participants provided their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the University Grants Commissions (UGC-MRP), Government of India and Department of Biotechnology (DBT-NER twinning Scheme) to carry out the work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

13104_2017_2467_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1. Oligonucleotides used as primers for amplification of different ESBL genes. Table S2. Primers used for characterization of integron.

13104_2017_2467_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Figure S1. PCR detection of IncY (765 bp) in transformants plasmid harbouring bla OXA-10. Lane 1: Negative control; Lane 2-8: 765 bp IncY. Figure S2. DNA finger printing of Enterobacteriace by ERIC PCR. Lane L: 10 Kb DNA hyper ladder I; Lane 1–9: ERIC pattern of E. coli Types 1–9; Lane 10–12: ERIC pattern of Klebsiella spp. Types 1–3. Lane 13: ERIC pattern of Proteus spp. ERIC Type-1. Figure S3. DNA finger printing of P. aeruginosa by REP PCR, P. aeruginosa Rep Types 1–11.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Maurya, A.P., Dhar, D., Basumatary, M.K. et al. Expansion of highly stable bla OXA-10 β-lactamase family within diverse host range among nosocomial isolates of Gram-negative bacilli within a tertiary referral hospital of Northeast India. BMC Res Notes 10, 145 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2467-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2467-2