Abstract

Background

To evaluate the effects of 8 weeks of Aerobic Physical Training (AET) on the mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative balance in the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) of leptin deficiency-induced obese mice (ob/ob mice).

Methods

Then, the mice were submitted to an 8-week protocol of aerobic physical training (AET) at moderate intensity (60% of the maximum running speed). In the oxidative stress, we analyzed Malonaldehyde (MDA) and Carbonyls, the enzymatic activity of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT) and Glutathione S Transferase (GST), non-enzymatic antioxidant system: reduced glutathione (GSH), and Total thiols. Additionally, we evaluated the gene expression of PGC-1α SIRT-1, and ATP5A related to mitochondrial biogenesis and function.

Results

In our study, we did not observe a significant difference in MDA (p = 0.2855), Carbonyl’s (p = 0.2246), SOD (p = 0.1595), and CAT (p = 0.6882) activity. However, the activity of GST (p = 0.04), the levels of GSH (p = 0.001), and Thiols (p = 0.02) were increased after 8 weeks of AET. Additionally, there were high levels of PGC-1α (p = 0.01), SIRT-1 (p = 0.009), and ATP5A (p = 0.01) gene expression after AET in comparison with the sedentary group.

Conclusions

AET for eight weeks can improve antioxidant defense and increase the expression of PGC-1α, SIRT-1, and ATP5A in PFC of ob/ob mice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity is a chronic metabolic disease that affects more than a billion people worldwide [1]. Characterized by individuals with body mass index (BMI) higher than 30 kg/m2, obesity has been listed as a risk factor for several chronic degenerative diseases [2]. Studies have demonstrated a variety of factors associated with the establishment of obesity, such as genetic, hormonal, and behavioral [3,4,5], wherein it has been described their relationship with areas of the Central Nervous System (CNS) that regulate energy balance and food intake [6, 7].

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that obesity might disturb cognitive centers by impairing neural networks in the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) [8]. The PFC is responsible for high executive functions such as attention, motor planning, and working memory, as well as the regulation of the limbic reward [9]. Due to the interaction between the limbic system and emotional regulation, PFC significantly influences food intake's behavioral control. Previous studies in the literature suggest that unhealthy eating behaviors result in poor executive functioning of the PFC, resulting in compromised self-control [10]. Since dorsolateral PFC plays a role in the supervision of eating and making healthy eating decisions, additional studies show that obese individuals have less left dorsolateral PFC activation after a meal compared with lean individuals, indicating dysfunction in the inhibitory mechanisms responsible for the control of the eating behavior and food choice [11]. In this context, obesity affects executive functions assessed through Delay Discounting, Penn Progressive Matrices, Picture Vocabulary, and Dimensional Change Card Sort Tests [12,13,14,15].

Contrariwise, Aerobic Physical Training (AET) [16,17,18] has been widely used in the prevention and treatment of obesity as well as in the enhancement of brain function, like neuromuscular rehabilitation protocol [19]. As a metabolic enhancer, exercise can improve lipolysis, immunity, oxidative metabolism, neuroplasticity, as well as mitochondria function, and oxidative stress resilience [20].

Oxidative stress is the process that can be defined as an imbalance between the production of the Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and their elimination [21, 22]. According to data in literature, several neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer, Parkinson, Huntington, and Multiple sclerosis) are associated with higher levels of ROS and the establishment of oxidative stress [21, 23, 24]. In the same way, recent data in the literature suggest the important role of ROS and oxidative stress in the brain dysfunctions associated with obesity [25, 26].

Despite the data in the literature demonstrating that exercise can reduce the deleterious effects induced by obesity on the brain, interestingly, up to now, there is a gap in the literature evaluating the specific effect of moderate aerobic exercise in a specific area of the brain, responsible for taking of decisions, and control of executive’s patterns linking oxidative stress and mitochondrial biogenesis. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate in PFC from ob/ob mice the levels of oxidative stress and the gene expression of mitochondrial biogenesis (i.e., PGC1α, SIRT-1, and ATP5A).

Methods

Ob Ob mice model

Male mice ob/ob (C57BL6) deficient in leptin aging 8 weeks old (LIM-07) were randomly divided into two groups: sedentary (SED, n = 6) and trained (TF, n = 6). The mice were kept in standard animal facility conditions. The mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment (22 ± 2 °C) with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and free access to tap water and food (Nuvilab—Nuvital Nutrientes S/A, Brazil).

Physical training

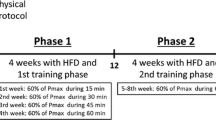

Trained mice were submitted to AET as previously described by Ferreira et al. [27]. Before starting the training, we conducted the capacity test where we placed the mice on the treadmill, applied the speed of 0.4 km/h, and increased the speed by 0.2 km/h every 3 min until the mice got to exhaustion, which characterizes the maximal running capacity. After four weeks, we re-evaluated each mouse, and the speed for the next week was corrected. The protocol training was conducted 5 × per week, at 60% of their max capacity, without inclination, for 60 min during eight weeks. Sedentary mice were placed on the treadmill but with the treadmill off. Forty-eight hours after the last session of the training protocol, we collected the skeletal muscle. We evaluated the citrate synthase activity to certify whether the moderate training-induced metabolic modulation.

Euthanasia

Forty-eight hours after the last training session, the mice were anesthetized with a dose of intraperitoneal ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mL/kg), and samples were collected by exsanguination [28].

Citrate synthase activity

Citrate synthase activity was performed as described by Le Page [29]. Briefly, the mixture containing TrisHCl (pH = 8.2), magnesium chloride (MgCl), ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA), 0.2–5.5 dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (E = 13.6 mmol/(ml cm), 3 acetyl CoA, 5 oxaloacetate and 0.3 mg/ml of sample. The enzymatic activity was evaluated at 412 nm for 2 min at a temperature of 25 °C. The data was expressed as U/mg of protein.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was also evaluated through the substances reactive to Thiobarbituric Acid (TBARS), as described by Buege and Aust [30]. Briefly, 300 µg of protein were mixed with 30% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 10 mM TRIS buffer (pH 7.4) in equal volumes. After centrifuging equals volumes of samples and thiobarbituric acid was mixed, followed by boil at 100 °C for 15 min. The pink pigment formed can be evaluated at 535 nm and expressed as mM/ mg protein [30].

Protein oxidation

Carbonyl was evaluated using the procedures described by Reznick and Packer [31]. Three hundred µg of protein was added to 30% (w/v) TCA and centrifuged at 1.180 g at 4 °C for 14 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mM 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine and incubated in a dark room for 1 h with shaking every 15 min. The samples were washed and centrifuged three times in ethyl acetate buffer 1:1 ratio, and the pellet was resuspended in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The samples read at 370 nm and expressed as µmol/ mg protein [31].

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD)

SOD activity was determined according to Misra and Fridovich [32]. Samples (300 µg/protein) were incubated in 0.05 M of carbonate buffer with EDTA (pH 10.2) at 30 °C following the addition of 150 mM epinephrine. The decrease in absorbance was monitored for 1.5 min at 480 nm and the results were expressed in U/mg protein [32].

Catalase (CAT)

CAT activity was conducted as described by Aebi [33]. Three hundred µg of protein supernatant was used in a medium containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 0.3 M of hydrogen peroxide. The assay was monitored at 240 nm for 3 min at 20 °C, and the results were expressed as U/ mg protein [33].

Glutathione S transferase (GST)

The activity of GST was performed as described by Habig et al. [34]. Two hundred μg of protein was added to a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) containing 1 mM EDTA. Then, 60 mM of reduced glutathione and 30 mM of 1-chloro-4, 4-dinitrobenzene were added to start the reaction, which was followed at 340 nm for 1 min [34]. The results were expressed in U/mg protein.

Reduced glutathione (GSH)

Reduced glutathione was assessed as described by Hissin and Hilf [35]. The samples were incubated in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 5 mM-EDTA (pH 8.0) plus 1 mg/ml of o-phthaldialdehyde (OPT) at room temperature for 15 min. Then, their fluorescences were measured at 350 nm excitation and 420 nm emission [35].

Total sulfhydryl

The total and protein-bound sulfhydryl group contents were determined as described by Aksenov and Markesbery [36]. The reduction of 5, 5-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) by thiol groups was measured in homogenates of 200 mg PFC, resulting in the generation of a yellow-stained compound, TNB, whose absorption is measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm [36].

RNA isolation and gene expression by RT-PCR

After tissue pulverization (50 mg), total RNA was prepared using Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations [37]. Total RNA was dissolved in RNase-free water and its integrity was checked in the 260/280 nm ratio. Samples with a ratio > 1.8 were kept at – 80 °C until processing by Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) analysis.

From the RNA extracted, we evaluated: PGC-1α, SIRT-1, ATP5A, and B2M (Table 1), through the Rotorgene 3000 (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) using Superscript™ III Platinum® One-Step Quantitative RT-PCR System (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, EUA). The cycle threshold (CT) of each targeted gene was compared with the CT of internal control and mRNA content was normalized by the 2−ΔΔCt formula [37].

Statistical analysis

The data had their distribution checked through the Shapiro–Wilk test, with a normal distribution. Then, the differences between groups were compared by using the Student t-test, and the data was expressed in mean ± SEM. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, prism. V6 (Graph Pad Software Inc, San Diego, USA).

Results

Initially, we measured peak velocity by incremental exercise test in sedentary and trained obese mice, with no difference between groups (SED: 1.00 ± 0.28 vs. TF: 1.17 ± 0.4 km/h, p = 0.17). However, after eight weeks of aerobic training, obese trained mice showed higher peak velocity than sedentary obese mice (SED: 0.80 ± 0.2 vs. TF: 1.26 ± 0.3 km, p = 0.01), demonstrating a greater capacity for racing. Our training also improves the activity of citrate synthase, a marker for training adaptation in skeletal muscle (SED: 19.28 ± 0.88 vs. TF: 26.91 ± 1.12 U/mg of protein, p = 0.0006). Our results demonstrate that exercise does not modulate oxidative stress biomarkers in the PFC of ob/ob mice, wherein no significant differences in both MDA (SED: 0.276 ± 0.10 µmol/ mg protein vs. TF: 0.437 ± 0.09 mM/mg protein, p = 0.2855) (Fig. 1A) and carbonyl (SED: 34.39 ± 11.38 µmol/mg protein vs. TF: 61.52 ± 16.97 µmol/mg protein, p = 0.2246) (Fig. 1B) levels were found.

Oxidative stress biomarkers in the PFC of ob/ob mice after eight weeks of AET. A MDA levels, B Carbonyl levels, p = 0.2855 and p = 0.2246 respectively. Enzymatic antioxidant defense in the PFC of ob/ob mice after eight weeks of AET. C Superoxide dismutase—SOD activity, D Catalase—CAT activity and E Glutathione-S-transferase—GST activity, p = 0.1595, p = 0.6882 and *p = 0.01 respectively. Non-enzymatic antioxidant defense in the PFC of ob/ob mice after eight weeks of AET. F Reduced glutathione (GSH) concentration, and G Total Thiols levels **p = 0.005; **p = 0.0016, respectively. Non-enzymatic antioxidant defense in the PFC of ob/ob mice after eight weeks of AET. A Reduced glutathione (GSH) concentration, and B Total Thiols levels **p = 0.005; **p = 0.0016, respectively. Sedentary (n = 6) and Trained (n = 6)

Although the exercise had not changed the oxidative stress-induced damage, it increased the overall antioxidant capacity. In the enzymatic system, while SOD (Fig. 1C) and CAT (Fig. 1D) activities remained unchanged, the exercise increased the GST activity (SED: 0.92 ± 0.34 U/mg protein vs. TF: 3.63 ± 0.73 U/mg protein; p = 0.04) (Fig. 1E). In addition, the non-enzymatic antioxidant components showed to be more responsive to exercise by increasing GSH content in 26% (SED: 5.07 ± 0.29 µmol /mg protein vs. TF: 6.43 ± 0.06 µmol/mg protein; p = 0.001) and the sulfhydryl groups in 66.7% (SED: 0.01 ± 0.002 mmol/mg protein vs. TF: 0.03 ± 0.001 mmol/mg protein; p = 0.02), Fig. 1F and G, respectively.

Additionally, evaluating genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, we demonstrate that AET up-regulates the expression of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) (p = 0.01) and Sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) (p = 0.009), Fig. 2A and B, respectively. Furthermore, gene expression of the Adenosine Tri Phosphate Synthase 5A (ATP5A), which encodes the ATP synthase into the mitochondrial electron transport chain, was also increased following AET (p = 0.01) (Fig. 2C).

Evaluation gene expression of ob/ob mice after eight weeks of AET in the PFC. A Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), B Sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) and C Adenosine tri phosphate synthase 5A gene (ATP5A). *p = 0.01; **p = 0.009 and *p = 0.02, respectively. Sedentary (n = 6) and T: trained (n = 6)

Discussion

The PFC, located in the front region of the brain, is implicated in several internal desires. It is the area responsible for executive function associated with the decision-making processes related to the choice between good and bad, conflicting thoughts, judging future consequences of present actions, and working regarding ambitions, prediction, and expectancies[38, 39]. In individuals with the normal function of the PFC, the ability to exert full control over the dietary desires for fatty and sugary food are effective, demonstrating the capacity for self-regulation/self-control expectancies [38, 39].

Some models of obesity demonstrate reduced signaling in PFC, and corroborative studies have also shown that increased activity in a specific region of the PFC moderates food cravings and consumption of these hyper-palatable foods, whereas the reduced activity of the same region can increase food consumption [40,41,42].

All regions in the brain are highly susceptible to reactive species (RS), especially due to the ATP-required high consumption of O2, amounts of excitatory amino acid transmitters and, calcium metabolism. Thus, the inappropriate balance between the production and removal of RS, and the mitochondrial dysfunction-related energy supply, might deregulate the whole brain function. This is an important concept because mitochondria play a fundamental role in the life and function of several cells in the brain, and cellular injury that impairs the capacity to generate ATP leads to cell death [43]. Mitochondria are dynamic organelles the function are modulated by the energy needs of tissues [44]. Exists a fine adjustment between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression that controls the assembly of the mitochondrial respiratory complex; therefore, the energetic demand controls phosphorylative capacity and the ATP supply [44]. In conditions of exercise, wherein exist a high energetic demand, mitochondrial biogenesis is triggered, activating the signaling cascade related to the SIRT-1, PGC-1α and nuclear respiratory factor-1/2 (NRF1/2), increasing the accurate communication between the nucleus and mitochondria to produce more mRNAs and mitochondrial proteins [45]. In turn, these increases in mitochondrial content, number, and energy demands need also to regulate the REDOX balance in mitochondria to maximize the capacity of mitochondria to perform oxidative phosphorylation without an increase in RS leaking or a decrease in antioxidant defense [46].

In some neurodegenerative diseases, mitochondrial damage reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity, increases RS production, leading to oxidative stress and negatively influencing brain function [47,48,49]. Data in the literature demonstrated the involvement of RS in alternating the control of satiety and hunger behavior [50, 51]. Specifically, in PFC, previous data in the literature demonstrate that obesity induced by high-fat diet, results in an increase of RS, oxidative stress biomarkers, and mitochondrial dysfunction [52, 53].

In our study, we demonstrated how exercise affects oxidative balance and mitochondrial biogenesis in the PFC of obese mice. Our findings demonstrate that AET improves antioxidant defense while up-regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and ATP synthase expressions. Our data showed that AET for 8 weeks improves GST activity, GSH, and total thiol levels, leading to an increase in antioxidant defense after 8 weeks. The activity of the glutathione pathway is mediated by tissue levels of reduced glutathione associated with the action of the glutathione reductase. This enzyme is associated with the plasma membrane participating in converting of GSSG to GSH through the oxidation of electron carriers, including nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate in its oxidized and reduced form (NADP+ and NADPH). These reactions are essential for the decrease of oxidative damage that affects cellular components participating in the removal of ROS and metabolic detoxification [54, 55].

Neves et al. [56] demonstrated that AET applied for 8 weeks decreased OS associated with increased antioxidant defenses in these CNS tissues. In addition, Aksu et al. [57], similarly, evaluated the acute and chronic effects of AET on the PFC, hippocampus, and striatum, their results showed that AET does not induce OS in these different brain areas [58]. These results corroborate with Flôres et al. [59] where the group showed that 12 weeks of AET increases GSH levels in PFC. Recently Comim et al. [60] showed that low-intensity training for 8 weeks was able to reverse the impairment in memory and learning, in addition to the decrease in oxidative stress biomarker in encephalic tissues, including PFC.

In addition, seeking to elucidate the possible interaction between antioxidant defense and OS biomarkers with other components of oxidative metabolism, we also evaluated the expression of important mitochondrial transcription factors, PGC-1α and SIRT-1 [61]. In this sense, it was that the trained group had increased both genes compared to the sedentary group. Contributing to our findings, Steiner [62] and colleagues performed 8 weeks of treadmill running (1 h/day, 6 days/week at 25 m/min and 5% incline), and showed increases in gene expression of PGC-1α and SIRT-1 in the brainstem, hippocampus and hypothalamus. Additionally, recent studies have shown that the contraction of skeletal muscle in response to aerobic exercise can activate the signaling pathway SIRT-1 / PGC-1α / Fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5) in the central nervous system, the precursor of irisin through metabolites including interleukin-6 and lactate that cross the blood–brain barrier promoting neurotrophic responses in different brains [63,64,65]. Supporting our data related to PGC-1α and SIRT-1 and the fact of AET may induce mitochondrial biogenesis, we quantify the levels of ATP5A, an important subunit of ATP synthase that can be used as an indicator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Our data showed that the levels of ATP5A in the trained group were higher than the control, showing that exercise is capable to induce mitochondrial subunits biogenesis. Contributing to our data, Braga et al. [66] showed that exercise during 5 week, one hour per day, 5 days per week at 60% of maximal capacity promoted an increase in the gene expression of OXPHOS subunits encoded by nDNA (Atp5a) in the lateral hypothalamus.

Taken together our data with previous data in the literature we can speculate that physical exercise can activate a complex communication between central and peripheric tissues leading an increase in brain metabolism [64, 67]. In a future study, we plan to evaluate the OXPHOS subunit’s function, protein levels, and mitochondrial respiration capacity to direct link aerobic training with an improvement in PFC function from obese individuals. Raising the relevance of physical training as a therapeutic strategy to combat the global epidemic of obesity.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrated that AET minimizes the effects of the obesity-induced OS in the PFC by activating antioxidant defenses and mitochondrial transcript factors, that can improve mitochondrial biogenesis and function.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AET:

-

Aerobic physical training

- ATP:

-

Adenosine tri phosphate

- ATP5A:

-

Adenosine tri phosphate synthase 5A

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- FNDC5:

-

Fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione production

- GST:

-

Glutathione S Transferase

- HII:

-

High-intensity interval aerobic physical training

- MDA:

-

Malonaldehyde

- OS:

-

Oxidative stress

- O2 :

-

Oxygen

- PFC:

-

Prefrontal cortex

- PGC-1α:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- RT-PCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SED:

-

Sedentary group

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- SIRT-1:

-

Sirtuin-1

- TBARS:

-

Thiobarbituric acid

- TF:

-

Trained group

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14.

Stoner L, Cornwall J. Did the American Medical Association make the correct decision classifying obesity as a disease? Australas Med J. 2014;7(11):462–4.

Ramachandrappa S, Farooqi IS. Genetic approaches to understanding human obesity. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(6):2080–6.

Brooks SJ, Cedernaes J, Schioth HB. Increased prefrontal and parahippocampal activation with reduced dorsolateral prefrontal and insular cortex activation to food images in obesity: a meta-analysis of fMRI studies. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60393.

Nobari H, Nejad HA, Kargarfard M, Mohseni S, Suzuki K, Carmelo-Adsuar J, Pérez-Gómez J. The effect of acute intense exercise on activity of antioxidant enzymes in smokers and non-smokers. Biomolecules. 2021;11(2):171.

Morton GJ, Meek TH, Schwartz MW. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(6):367–78.

Gluck ME, Viswanath P, Stinson EJ. Obesity, appetite, and the prefrontal cortex. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(4):380–8.

Heinitz S, Reinhardt M, Piaggi P, Weise CM, Diaz E, Stinson EJ, Venti C, Votruba SB, Wassermann EM, Alonso-Alonso M, et al. Neuromodulation directed at the prefrontal cortex of subjects with obesity reduces snack food intake and hunger in a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(6):1347–57.

Xu X, Deng ZY, Huang Q, Zhang WX, Qi CZ, Huang JA. Prefrontal cortex-mediated executive function as assessed by Stroop task performance associates with weight loss among overweight and obese adolescents and young adults. Behav Brain Res. 2017;321:240–8.

Chen J, Papies EK, Barsalou LW. A core eating network and its modulations underlie diverse eating phenomena. Brain Cogn. 2016;110:20–42.

Gluck ME, Alonso-Alonso M, Piaggi P, Weise CM, Jumpertz-von Schwartzenberg R, Reinhardt M, Wassermann EM, Venti CA, Votruba SB, Krakoff J. Neuromodulation targeted to the prefrontal cortex induces changes in energy intake and weight loss in obesity. Obesity. 2015;23(11):2149–56.

Syan SK, Owens MM, Goodman B, Epstein LH, Meyre D, Sweet LH, MacKillop J. Deficits in executive function and suppression of default mode network in obesity. NeuroImage Clinical. 2019;24:102015.

Favieri F, Forte G, Casagrande M. The executive functions in overweight and obesity: a systematic review of neuropsychological cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2126.

Mamrot P, Hanć T. The association of the executive functions with overweight and obesity indicators in children and adolescents: a literature review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:59–68.

Steward T, Juaneda-Seguí A, Mestre-Bach G, Martínez-Zalacaín I, Vilarrasa N, Jiménez-Murcia S, Fernández-Formoso JA, de Las V, Heras M, Custal N, Virgili N, et al. What difference does it make? Risk-taking behavior in obesity after a loss is associated with decreased ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1551.

Fonseca-Junior SJ, Sa CG, Rodrigues PA, Oliveira AJ, Fernandes-Filho J. Physical exercise and morbid obesity: a systematic review. Arq bras cir dig. 2013;26(1):67–73.

Young MF, Valaris S, Wrann CD. A role for FNDC5/Irisin in the beneficial effects of exercise on the brain and in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;62(2):172–8.

Sinaei M, Alaei H, Nazem F, Kargarfard M, Feizi A, Talebi A, Esmaeili A, Nobari H, Pérez-Gómez J. Endurance exercise improves avoidance learning and spatial memory, through changes in genes of GABA and relaxin-3, in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;566:204–10.

Yazdani M, Chitsaz A, Zolaktaf V, Saadatnia M, Ghasemi M, Nazari F, Chitsaz A, Suzuki K, Nobari H. Can early neuromuscular rehabilitation protocol improve disability after a hemiparetic stroke? A pilot study. Brain Sci. 2022;12(7):816.

Powers SK, Radak Z, Ji LL. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: past, present and future. J Physiol. 2016;594(18):5081–92.

Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634–58.

Nobari H, Fashi M, Eskandari A, Pérez-Gómez J, Suzuki K. Potential improvement in rehabilitation quality of 2019 novel coronavirus by isometric training system; is there “muscle-lung cross-talk”? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6304.

Ferreira DJ, Sellitti DF, Lagranha CJ. Protein undernutrition during development and oxidative impairment in the central nervous system (CNS): potential factors in the occurrence of metabolic syndrome and CNS disease. J Dev Origins Health Dis. 2016;7:513.

Chortane OG, Hammami R, Amara S, Chortane SG, Suzuki K, Oliveira R, Nobari H. Effects of multicomponent exercise training program on biochemical and motor functions in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Sustainability. 2022;14(7):4112.

Mullins CA, Gannaban RB, Khan MS, Shah H, Siddik MAB, Hegde VK, Reddy PH, Shin AC. Neural underpinnings of obesity: the role of oxidative stress and inflammation in the brain. Antioxidants. 2020;9(10):1018.

Nobari H, Gandomani EE, Reisi J, Vahabidelshad R, Suzuki K, Volpe SL, Pérez-Gómez J. Effects of 8 weeks of high-intensity interval training and spirulina supplementation on immunoglobin levels, cardio-respiratory fitness, and body composition of overweight and obese women. Biology. 2022;11(2):196.

Ferreira JC, Rolim NP, Bartholomeu JB, Gobatto CA, Kokubun E, Brum PC. Maximal lactate steady state in running mice: effect of exercise training. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34(8):760–5.

Evangelista FS, Muller CR, Stefano JT, Torres MM, Muntanelli BR, Simon D, Alvares-da-Silva MR, Pereira IV, Cogliati B, Carrilho FJ, et al. Physical training improves body weight and energy balance but does not protect against hepatic steatosis in obese mice. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):10911–9.

Le Page C, Noirez P, Courty J, Riou B, Swynghedauw B, Besse S. Exercise training improves functional post-ischemic recovery in senescent heart. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44(3):177–82.

Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–10.

Reznick AZ, Packer L. Oxidative damage to proteins: spectrophotometric method for carbonyl assay. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:357–63.

Misra HP, Fridovich I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247(10):3170–5.

Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6.

Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249(22):7130–9.

Hissin PJ, Hilf R. A fluorometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissues. Anal Biochem. 1976;74(1):214–26.

Aksenov MY, Markesbery WR. Changes in thiol content and expression of glutathione redox system genes in the hippocampus and cerebellum in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2001;302(2–3):141–5.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8.

Lowe CJ, Reichelt AC, Hall PA. The prefrontal cortex and obesity: a health neuroscience perspective. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(4):349–61.

Lowe CJ, Morton JB, Reichelt AC. Adolescent obesity and dietary decision making—a brain-health perspective. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2020;4(5):388–96.

Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Arora J, Giannini C, Kubat J, Malik S, Van Name MA, Santoro N, Savoye M, Duran EJ. Altered brain response to drinking glucose and fructose in obese adolescents. Diabetes. 2016;65(7):1929–39.

Reichelt AC. Adolescent maturational transitions in the prefrontal cortex and dopamine signaling as a risk factor for the development of obesity and high fat/high sugar diet induced cognitive deficits. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:189.

Rösch SA, Schmidt R, Lührs M, Ehlis A-C, Hesse S, Hilbert A. Evidence of fNIRS-based prefrontal cortex hypoactivity in obesity and binge-eating disorder. Brain Sci. 2020;11(1):19.

Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407.

Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267–73.

Gureev AP, Shaforostova EA, Popov VN. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis as a way for active longevity: interaction between the Nrf2 and PGC-1α signaling pathways. Front Genet. 2019;10:435.

Banerjee R. Redox outside the box: linking extracellular redox remodeling with intracellular redox metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4397–402.

Hajjar I, Hayek SS, Goldstein FC, Martin G, Jones DP, Quyyumi A. Oxidative stress predicts cognitive decline with aging in healthy adults: an observational study. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):17.

Singh A, Kukreti R, Saso L, Kukreti S. Oxidative stress: a key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules. 2019;24(8):1583.

Hoyos CM, Stephen C, Turner A, Ireland C, Naismith SL, Duffy SL. Brain oxidative stress and cognitive function in older adults with diabetes and pre-diabetes who are at risk for dementia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;184:109178.

Crispino M, Trinchese G, Penna E, Cimmino F, Catapano A, Villano I, Perrone-Capano C, Mollica MP. Interplay between peripheral and central inflammation in obesity-promoted disorders: The impact on synaptic mitochondrial functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):5964.

Horvath TL, Andrews ZB, Diano S. Fuel utilization by hypothalamic neurons: roles for ROS. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(2):78–87.

de Farias BX, Costa AB, Engel NA, de Souza Goldim MP, da Rosa TC, Cargnin-Cavalho A, Fortunato JJ, Petronilho F, Jeremias IC, Rezin GT. Donepezil prevents inhibition of cerebral energetic metabolism without altering behavioral parameters in animal model of obesity. Neurochem Res. 2020;45(10):2487–98.

Nuzzo D, Galizzi G, Amato A, Terzo S, Picone P, Cristaldi L, Mulè F, Di Carlo M. Regular intake of pistachio mitigates the deleterious effects of a high fat-diet in the brain of obese mice. Antioxidants. 2020;9(4):317.

Couto N, Wood J, Barber J. The role of glutathione reductase and related enzymes on cellular redox homoeostasis network. Free Radical Biol Med. 2016;95:27–42.

Gu F, Chauhan V, Chauhan A. Glutathione redox imbalance in brain disorders. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18(1):89–95.

Neves BH, Menezes J, Souza MA, Mello-Carpes PB. Physical exercise prevents short and long-term deficits on aversive and recognition memory and attenuates brain oxidative damage induced by maternal deprivation. Physiol Behav. 2015;152(Pt A):99–105.

Aksu I, Topcu A, Camsari UM, Acikgoz O. Effect of acute and chronic exercise on oxidant-antioxidant equilibrium in rat hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and striatum. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452(3):281–5.

Jahangiri Z, Gholamnezhad Z, Hosseini M. The effects of exercise on hippocampal inflammatory cytokine levels, brain oxidative stress markers and memory impairments induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Metab Brain Dis. 2019;34(4):1157–69.

Flores MF, Martins A, Schimidt HL, Santos FW, Izquierdo I, Mello-Carpes PB, Carpes FP. Effects of green tea and physical exercise on memory impairments associated with aging. Neurochem Int. 2014;78:53–60.

Comim CM, Soares JA, Alberti A, Freiberger V, Ventura L, Dias P, Schactae AL, Grigollo LR, Steckert AV, Martins DF. Effects of low-intensity training on the brain and muscle in the congenital muscular dystrophy 1D model. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:6613.

Gerhart-Hines Z, Rodgers JT, Bare O, Lerin C, Kim SH, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Wu Z, Puigserver P. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1alpha. EMBO J. 2007;26(7):1913–23.

Steiner JL, Murphy EA, McClellan JL, Carmichael MD, Davis JM. Exercise training increases mitochondrial biogenesis in the brain. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(4):1066–71.

Muller P, Duderstadt Y, Lessmann V, Muller NG. Lactate and BDNF: key mediators of exercise induced neuroplasticity? J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):1136.

Pedersen BK. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(7):383–92.

Severinsen MCK, Pedersen BK. Muscle-organ crosstalk: the emerging roles of myokines. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(4):594–609.

Braga RR, Crisol BM, Brícola RS, Sant’ana MR, Nakandakari SC, Costa SO, Prada PO, da Silva AS, Moura LP, Pauli JR. Exercise alters the mitochondrial proteostasis and induces the mitonuclear imbalance and UPRmt in the hypothalamus of mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–13.

Ding Q, Vaynman S, Souda P, Whitelegge JP, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise affects energy metabolism and neural plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus as revealed by proteomic analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(5):1265–76.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Toscano A.E. responsible for the Studies in Nutrition and Phenotypic Plasticity Unit (FINEP number 01.08.0655.00).

Funding

This study was not financial supported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSSF, LLSS, RSH and CJL conceived the study idea and design. MSSF, GCJS, DSF, and CJL formulated the aerobic exercise training intervention. MSSF, AASP, SCA, and ARP conducted animal model selection and care. MSSF, AASP, EMB, and ARP conducted interventions. SCA and MDTL performed RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis, MSSF, and AAPS performed the Oxidative Balance analysis, MSSF, RSH, and CJL wrote the manuscript with review, editing and final approval from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0 and according to the Arouca Law (No 11.794/ October 8, 2008) and the Normative Resolutions of the National Council for Animal Experiments Control—CONCEA, both regulated by Brazilian Federal Constitution. All experiments in this manuscript were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA, number 040/17) of the Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

de Sousa Fernandes, M.S., Aidar, F.J., da Silva Pedroza, A.A. et al. Effects of aerobic exercise training in oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis markers on prefrontal cortex in obese mice. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 14, 213 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00607-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00607-x