Abstract

Background

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a food-borne intestinal human parasite that causes outbreaks of diarrhea. There is a need for efficient laboratory methods for strain-level characterization to assist in outbreak investigations. By using next generation sequencing, genomic sequences can be obtained and compared to identify potential genotyping markers. However, there is no method available to propagate this parasite in the laboratory. Therefore, genomic DNA must be extracted from oocysts purified from human stool. The objective of this study was to apply optimized methods to purify C. cayetanensis oocysts and extract DNA in order to obtain high-quality whole genome sequences with minimum contamination of DNA from other organisms.

Results

Oocysts from 21 human stool specimens were separated from other stool components using discontinuous density gradient centrifugation and purified further by flow cytometry. Genomic DNA was used to construct Ovation Ultralow libraries for Illumina sequencing. MiSeq sequencing reads were taxonomically profiled for contamination, de novo assembled, and mapped to a draft genome available in GenBank to assess the quality of the resulting genomic sequences. Following all purification steps, the majority (81–99%) of sequencing reads were from C. cayetanensis. They could be assembled into draft genomes of around 45 MB in length with GC-content of 52%.

Conclusions

Density gradients performed in the presence of a detergent followed by flow cytometry sorting of oocysts yielded sufficient genomic DNA largely free from contamination and suitable for whole genome sequencing of C. cayetanensis. The methods described here will facilitate the accumulation of genomic sequences from various samples, which is a prerequisite for the development of typing tools to aid in outbreak investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a food-borne coccidian pathogen of humans associated with cyclosporiasis outbreaks in the U.S. almost every summer [1,2,3]. There is little data available on the genetic variation of this parasite. Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions between 18S and 28S rRNA genes have been used as molecular typing tools for other organisms. However, ITS1 variability has been reported within individual C. cayetanensis oocysts, rendering this region unsuitable for subspecies differentiation [4]. On the other hand, other parts of the C. cayetanensis genome, including ribosomal RNA genes, heat shock protein genes, mitochondrial and apicoplast genomes, have little or no sequence variation between samples from various geographical regions [5,6,7,8]. A multi-locus sequence typing method based on five microsatellites has been developed [9]. However, this method suffers from low success rate (approximately 50–60%) due to frequent uninterpretable sequence results [9, 10]. More information about C. cayetanensis genomic variation between and within various geographical regions are needed to aid investigations of outbreaks and sporadic cases.

There is no method available to propagate C. cayetanensis in the laboratory, neither in vitro or in vivo [11]. Therefore, genomic DNA must be extracted from limited human stool specimens collected from clinical cases of cyclosporiasis. Isolating and purifying the transmissible stage of the parasite (oocysts) is complicated by the complexity of stool compositions that vary in each preparation. Moreover, the outer wall of C. cayetanensis oocyst is resistant to many commonly used DNA extraction techniques [12]. Next generation sequencing (NGS) has recently been used to obtain draft assemblies of the genome of C. cayetanensis from two different geographic regions [13, 14]. These studies were based on genomic sequences obtained from oocysts purified by density gradients and flow cytometry sorting. However, the focus of these publications was on the analysis of the genome sequence data; the descriptions of the laboratory methods to purify the oocysts and obtain genomic DNA were necessarily brief. The present study provides a detailed description of the laboratory methods involved in the genomic sequencing of C. cayetanensis. We applied these methods to stool samples from different countries and U.S. outbreaks, collected in three different stool preservatives or transport media, to ensure reproducibility.

Results

Discontinuous density gradient purification of oocysts

The addition of Alconox (final concentration 0.75% w/v) to the gradient purification steps resulted in considerably less contamination (Fig. 1). Lower concentrations of Alconox yielded preparations with more contamination (data not shown). The addition of Alconox benefited the purification of oocysts from stool preserved in potassium dichromate, fixed in a zinc–polyvinyl alcohol (Zn–PVA) based fixative, or collected in a transport medium (Cary-Blair) in our study.

Separating oocysts from contaminants using flow cytometry

Gradient purified oocysts were separated from remaining contaminants through flow cytometry sorting. Bi-parameter scatter and fluorescence dot plots of representative oocyst preparations are shown in Fig. 2. Scatter plots, oocyst size and internal complexity alone failed to separate oocysts from all debris (see gate region P2). Therefore, fluorescence dot plots were used to improve the separation (see gate region P1). Flow cytometry sorting was only practical for oocyst preparations that had reached a sufficient degree of purity in the gradient steps; preparations that contained too much stool residue would either clog the instrument or take an exorbitant long time to sort in the flow cytometer. For this reason, samples purified without Alconox were generally less successful in the flow cytometry process: in the example illustrated in Fig. 2, the proportion of oocyst events among all events was only 2.1% for oocysts purified without Alconox (panels a and b), but 40.3% for oocysts purified with Alconox (panels c and d).

Representative images of flow cytometry sorting of oocysts purified without (a and b) and with (c and d) Alconox in the gradient purification process. a and c Separation based on scatter; b and d separation based on fluorescence (FITC-A, filter 530/30 nm and PerCP-A, Cy 5.5 filter 695/40 nm). Oocysts (red events in gates P1 and P2) were sorted on logical “AND” function. Both sorted oocysts and sorted oocysts with conflicts were collected in single-cell mode

Genomic DNA extraction from purified oocysts

Genomic DNA was extracted from unsorted oocysts as well as sorted oocysts. DNA was extracted using mechanical disruption using freeze-and-thaw cycles. A majority of oocysts needed up to 25 cycles of freeze-and-thaw to disrupt the tough walls of oocysts and sporocysts (where present). Less than 10% of the oocysts showed disruption after 5 cycles of freeze-and-thaw. Purified oocysts before and after 15 cycles of freeze-and-thaw are shown in Fig. 3.

Yield of genomic DNA extractions ranged from 5 to 15 ng per million oocysts, which was about 10%–30% of the total genomic DNA theoretically present in those oocysts (assuming a haploid genome size of 45 Mb without sporulation). The peak size of genomic DNA extracted using this method was around 12 kb (Fig. 4).

Bioinformatic analysis of Illumina reads

Genomic DNAs from unsorted and sorted oocysts were used to generate Illumina sequencing reads. Trimmed reads were then mapped to the CDC:HCNY16:01 draft genome assembly (Table 1) and analyzed for contaminants by metagenomic profiling (Fig. 5).

Representative heat maps showing the relative abundance of taxa identified by MetaPhlAn in genomic sequencing datasets obtained from unsorted and sorted oocysts from specimen CDC:HCGM01:97. a Before flow-sorting; b flow-sorted oocysts. The database used does not contain signatures for Cyclospora species. Therefore, reads identified as Eimeria and other related eukaryotes could be C. cayetanensis sequences

Flow cytometry sorting had a major impact on the quality of the resulting Illumina sequencing data. Metagenomic profiling analysis revealed that the majority of reads from unsorted oocysts matched prokaryotic sequences, whereas relatively few prokaryotic sequences were identified in the flow-sorted oocysts (Fig. 5a and b, respectively). Furthermore, less than 25% of the reads from un-sorted oocysts could be mapped to the CDC:HCNY16:01 draft genome assembly, whereas more than 80% of the reads from sorted oocysts could be mapped to the same genome draft (Table 1).

De novo assembly of draft genomes of C. cayetanensis samples

DNA extracted from flow-sorted oocysts were used to obtain draft genome assemblies. Reads from Illumina libraries with different insert sizes were pooled together and assembled de novo. A comparison of these new genome assemblies is summarized in Table 2. The new assemblies had contig numbers between 669 and 2827. The total length of these contigs and the GC content were consistent with published draft genome assemblies of C. cayetanensis strains CDC:HCNY16:01 and CHN_HEN01 (GenBank accession numbers ASM130573v1 and ASM76915v2).

Discussion

Next generation sequencing (NGS) was recently used to obtain draft genome assemblies of C. cayetanensis, providing opportunities to explore metabolism, pathogenicity, and genetic variation of this parasite [9, 10, 13, 14]. These studies were performed using similar methods as presented in this study, but the publications only briefly mention the laboratory methods involved without enough specifics to allow other researchers to replicate them. Here we described the detailed laboratory methods for purifying and processing oocysts from stool to obtain high quality NGS data.

A previous study has concluded that a detachment solution (containing disodium pyrophosphate) can improve the recovery of C. cayetanensis from stool during density gradient purification compared to 0.01% Tween 20 [15]. Moreover, the addition of 0.1% of detergent Alconox in the wash solution can improve oocyst recovery from environmental samples [16]. In this study, we found that the addition of 0.75% of Alconox could substantially improve the separation of oocysts from fecal contaminants during gradient purifications. The use of Alconox resulted in purification that was more efficient and therefore applicable to a wider range of stools, including those with low oocyst counts.

Partially purified oocysts can be further separated from contaminants using flow cytometry sorting. Flow cytometry was successfully used to separate Cyclospora oocysts from stool debris in previous studies [17, 18]. In this study, three factors facilitated the efficient separation of oocysts from stool debris using flow cytometry: First, oocysts exhibit autofluorescence. Second, PI staining helped discriminate debris from oocysts since the latter were not PI stained. Third, Alconox used in the density gradient purification greatly reduced contaminant load prior to flow cytometry sorting; specimens purified without Alconox contained more debris that slowed down or inhibited the flow cytometry process. A 488 nm laser with fluorescence filters appropriate for FITC and PerCp-Cy5.5 were used to separate oocysts from debris for all four specimens included in this study. However, depending on the particular composition of contaminants, sorting of other specimens may benefit from the use of alternative filter sets appropriate for PI. We have successfully used filters for r-phycoerythrin (PE), PE-Texas Red, and PE-Cy7 in the past. Lasers with shorter wavelengths (violet and UV) can enhance separation since oocyst autofluorescence is shifted even further from the debris (data not shown).

Draft genome assemblies obtained from purified oocysts in this study had comparable assembly statistics to the two previously published assemblies of C. cayetanensis, samples CDC:HCNY16:01 and the CHN_HEN01 [13, 14]. Sample CDC:HCNY16:01 was processed using the same methods as described in this study. The assembly for CHN_HEN01 was obtained using other methods for library preparation and sequencing (454 GS-FLX complemented with Illumina 100 cycles) but similar methods for purifying and extracting DNA from oocysts (excluding Alconox treatment). These findings indicate that the laboratory methods described here are reproducible and generally result in good quality genome assemblies of C. cayetanensis.

Conclusions

Laboratory methods were applied to obtain C. cayetanensis genomic sequences using human stool specimens as starting material. A key step to obtaining good quality genomic sequences was flow cytometry sorting of the oocysts to remove contaminants. The addition of Alconox in the discontinuous gradient purification steps greatly improved the purification efficiency and thereby enabled the flow cytometry process for a wider range of stools. The genomic drafts obtained in this study represented at least seven separate U.S. outbreaks and four different countries, providing a good starting material for exploring the genetic diversity of this parasite.

Methods

Stool specimens

Twenty-one human stool specimens were selected for this study due to the presence of relatively high numbers of oocysts (large volume and/or high parasite load as estimated by UV-fluorescence microscopy). We included twelve specimens collected from seven separate U.S. outbreaks: Washington D.C. in 1996 (HCDC004_96); Rhode Island in 1997 (HCRI001_97); Nebraska in 2016 (HCNE181_16); and Texas in 2013 (HCTX119_13 and HCTX365_13), 2014 (HCTX535_14 and HCTX569_14), 2015 (HCTX542_15 and HCTX547_15) and 2016 (HCTX460_16, HCTX495_16 and HCTX503_16). Also included were 9 specimens collected in four different countries: Guatemala (HCGM002_97, HCGM011_97 and (HCGM012_97), Nepal (HCNP016_97), Indonesia (HCJK001_14, HCJK008_15, HCJK011_15 and HCJK015_15), and Mexico (HCMX010_16). Specimens collected prior to 2013 and specimens collected in countries outside the U.S. were preserved in 2.5% (w/v) aqueous potassium dichromate and stored at 4 °C following collection (n = 11). Specimen HCNE181_16 was collected in Cary-Blair transport medium. The remaining specimens (n = 9) were collected in Zn–PVA.

Discontinuous density gradient purification of oocysts from stool

Preservatives were removed by centrifugation (3200×g) at 4 °C for 10 min and decanting the supernatant. The resulting pellets were washed with 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). Stool suspensions were passed through a disposable 125 µm flat sieve (e.g. SATA RPS® 0.3 L filter 1010420, SATA USA, Spring Valley, MN) to remove large particles, centrifuged as described above and re-suspended in PBS at a 1:3 ratio (v/v). Samples were gently mixed (to avoid foaming) with an equal volume of 1.5% (w/v) Alconox detergent solution (Alconox Inc., White Plains, NY) and subjected to discontinuous sucrose gradient purification as previously described for Cryptosporidium [19, 20] with the following modifications for Cyclospora purification. In the sucrose gradient centrifugation step, Cyclospora oocysts accumulated at the interface between the two sucrose layers (the high-density fraction), as well as the interface between the sample overlay and the top sucrose layer (the low-density fraction). Each of these fractions were collected separately, diluted to three times its volume with deionized water (dH2O), and centrifuged (3200×g for 10 min) to pellet oocysts. The pellets were then re-suspended in PBS to half of the original volume and then gently mixed with 1.5% Alconox to a final concentration of 0.75%. The sucrose gradient purification was repeated once more. The sucrose gradient-purified oocyst pellets were diluted with PBS at a ratio of approximately 1:6 (v/v).

Sucrose gradient purified oocysts were then subjected to cesium chloride gradient purification as previously described [19] with one critical modification. The oocyst-containing fraction of the gradient (~ 1 ml collected from the interface between the sample layer and the cesium chloride layer) was diluted with dH2O to approximately three times the starting volume (i.e., to ~ 3 ml total volume or more) and centrifuged (16,300×g for 3 min) to pellet oocysts. Pelleted oocysts were re-suspended in PBS, pooled together, and quantified using an improved Neubauer hemacytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA).

Flow cytometry sorting

Gradient-purified C. cayetanensis oocysts were sorted by flow cytometry using a BD FACSAria III (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) equipped with blue (488 nm) and red (633 nm) lasers. Oocysts were diluted with sheath fluid appropriately for a sorting efficiency rate ≥ 45% and processed in the single-cell sorting mode using a 70 µm nozzle at 70 psi. Propidium iodide (PI) was added to the oocyst preparation at a final concentration of 1.0 µg/ml to label “dead” cells by binding to their DNA, thus increasing the shift away from oocysts because oocysts do not take up PI due to their intact oocyst wall [21]. Oocysts were identified by their size (approximately 8–10 µm) by forward scatter (FSC), their internal complexity by side scatter (SSC), and their autofluorescence emission properties when excited by 488 nm light using fluorescence filters appropriate for fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), tandem fluorochrome peridinin chlorophyll protein, and cyanine 5.5 (PerCP-Cy5.5).

Genomic DNA extraction

Twenty-five cycles of freeze-and-thaw (freeze for 1 min by immersion in an ethanol/dry ice bath followed by thawing at 95 °C for 1 min in a heat block) was used to mechanically break open the purified oocysts. Genomic DNA was extracted from ruptured oocysts using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of extracted genomic DNA was determined using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Cleveland, OH). The integrity of genomic DNA was analyzed by electrophoresis using Genomic DNA Analysis ScreenTape on a 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

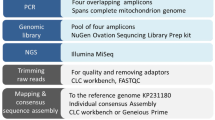

Genomic DNA library construction and Illumina sequencing

Genomic DNA (10 ng) was sheared in an M220 Focused-ultrasonicator™ (Covaris Inc., Woburn, MA) using settings for an average fragment of 300, 500, or 700 base pairs. Genomic libraries were constructed for Illumina sequencing using Ovation® Ultralow Library Systems V2 (NuGEN Technologies Inc., San Carlos, CA) [22]. Libraries were barcoded to facilitate pooling during subsequent sequencing runs. Size distribution and concentration of genomic DNA libraries were analyzed by electrophoresis using Genomic DNA Analysis ScreenTape and D1000 ScreenTape on a 2200 TapeStation (Agilent). Barcoded genomic DNA libraries were pair-end sequenced using Illumina MiSeq Reagent v3 (600 cycles, 2 × 300 bp) kits (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA).

Bioinformatic analysis

Raw sequence data were assessed for quality using FASTQC v0.11.5. AdaptorRemoval v2.2.2 [23] was used to remove adaptor sequences from reads and to merge overlapping paired reads into consensus sequences. Genome assembly was performed using SPAdes v3.12.0 [24]. Contigs derived from prokaryotic human gut microbiota were removed with BBMap v35.82 [25]. CLC Genomics Workbench Map to Reference assembler (QIAGEN) was used to map reads to the draft genome assembly of strain CDC:HCNY16:01 (GenBank Accession No. ASM130573v1).

Metagenomic analysis was performed to estimate the degree of contamination in the sequences obtained at various steps of oocyst purification. Sequencing reads were profiled for taxonomic diversity by assessing the percentage of data arising from certain contaminating organisms using MetaPhlAn [26] and signature database version 2.0. This database does not contain signatures from Cyclospora species.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. foodborne outbreaks of cyclosporiasis—2000–2016. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/foodborneoutbreaks.html. Accessed 13 July 2018.

Herwaldt BL. Cyclospora cayetanensis: a review, focusing on the outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(4):1040–57.

Ortega YR, Sanchez R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):218–34.

Riner DK, Nichols T, Lucas SY, Mullin AS, Cross JH, Lindquist HD. Intragenomic sequence variation of the ITS-1 region within a single flow-cytometry-counted Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts. J Parasitol. 2010;96(5):914–9.

Cinar HN, Gopinath G, Jarvis K, Murphy HR. The complete mitochondrial genome of the foodborne parasitic pathogen Cyclospora cayetanensis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128645.

Cinar HN, Qvarnstrom Y, Wei-Pridgeon Y, Li W, Nascimento FS, Arrowood MJ, et al. Comparative sequence analysis of Cyclospora cayetanensis apicoplast genomes originating from diverse geographical regions. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):611.

Ogedengbe ME, Qvarnstrom Y, da Silva AJ, Arrowood MJ, Barta JR. A linear mitochondrial genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis (Eimeriidae, Eucoccidiorida, Coccidiasina, Apicomplexa) suggests the ancestral start position within mitochondrial genomes of eimeriid coccidia. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45(6):361–5.

Tang K, Guo Y, Zhang L, Rowe LA, Roellig DM, Frace MA, et al. Genetic similarities between Cyclospora cayetanensis and cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. in apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:358.

Guo Y, Roellig DM, Li N, Tang K, Frace M, Ortega Y, et al. Multilocus sequence typing tool for Cyclospora cayetanensis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(8):1464–7.

Li J, Chang Y, Shi KE, Wang R, Fu K, Li S, et al. Multilocus sequence typing and clonal population genetic structure of Cyclospora cayetanensis in humans. Parasitology. 2017;144(14):1890–7.

Eberhard ML, Ortega YR, Hanes DE, Nace EK, Do RQ, Robl MG, et al. Attempts to establish experimental Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in laboratory animals. J Parasitol. 2000;86(3):577–82.

Lalonde LF, Gajadhar AA. Highly sensitive and specific PCR assay for reliable detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(14):4354–8.

Qvarnstrom Y, Wei-Pridgeon Y, Li W, Nascimento FS, Bishop HS, Herwaldt BL, et al. Draft genome sequences from Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts purified from a human stool sample. Genome Announc. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.01324-15.

Liu S, Wang L, Zheng H, Xu Z, Roellig DM, Li N, et al. Comparative genomics reveals Cyclospora cayetanensis possesses coccidia-like metabolism and invasion components but unique surface antigens. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:316.

Riner DK, Mullin AS, Lucas SY, Cross JH, Lindquist HD. Enhanced concentration and isolation of Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts from human fecal samples. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;71(1):75–7.

Shields JM, Lee MM, Murphy HR. Use of a common laboratory glassware detergent improves recovery of Cryptosporidium parvum and Cyclospora cayetanensis from lettuce, herbs and raspberries. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;153(1–2):123–8.

Hussein EM, El-Moamly AA, Dawoud HA, Fahmy H, El-Shal HE, Sabek NA. Real-time PCR and flow cytometry in detection of Cyclospora oocysts in fecal samples of symptomatic and asymptomatic pediatrics patients. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2007;37(1):151–70.

Dixon BR, Bussey JM, Parrington LJ, Parenteau M. Detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts in human fecal specimens by flow cytometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(5):2375–9.

Arrowood MJ, Donaldson K. Improved purification methods for calf-derived Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using discontinuous sucrose and cesium chloride gradients. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43(5):89S.

Arrowood MJ, Sterling CR. Isolation of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients. J Parasitol. 1987;73(2):314–9.

Riccardi C, Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(3):1458–61.

Nascimento FS, Wei-Pridgeon Y, Arrowood MJ, Moss D, da Silva AJ, Talundzic E, et al. Evaluation of library preparation methods for Illumina next generation sequencing of small amounts of DNA from foodborne parasites. J Microbiol Methods. 2016;130:23–6.

Schubert M, Lindgreen S, Orlando L. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:88.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77.

Bushnell B. BBMap short-read aligner, and other bioinformatics tools. http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/. Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Segata N, Waldron L, Ballarini A, Narasimhan V, Jousson O, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic microbial community profiling using unique clade-specific marker genes. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):811–4.

Authors’ contributions

YQ wrote the manuscript and assisted in study design, YWP performed the laboratory experiments and initiated the drafting of the manuscript; EVR and SP performed the genome assemblies, GS performed the metagenomic profiling analysis; FSN provided assistance with sample processing and NGS sequencing; DMM performed the flow cytometry experiments; ET provided bioinformatic support; MJA assisted in study design and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Biotechnology Core Facility Branch in the CDC’s National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases provided technical support. Authors thank Cathy Snider, Tanty Rachmawaty, Kristine McVey, and James R. Adams for providing stool specimens and Yueli Zheng for bioinformatics assistance. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The genomic sequencing assemblies generated in this study are available in NCBI Assembly repository under accession numbers ASM201990v1 (CDC:HCRI01:97), ASM201945v1 (CDC:TX69:14), ASM289344v1 (CDC:HCGM11:97), ASM201947v1 (CDC:HCJK01:14). Assemblies for the other samples have been submitted to NCBI for immediate release upon their review but have not yet been assigned accession numbers. All genome assemblies and raw sequence reads are available from the corresponding author on request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human stool specimens were originally collected for clinical diagnostic purpose and used in accordance with the Human Subjects Research Protocol titled “Use of coded specimens for Cyclospora genomics research”, approved by the Human Research Protection Office in the CDC Center for Global Health.

Funding

This study was made possible by support from the CDC`s Advanced Molecular Detection and Response to Infectious Disease Outbreaks Initiative. Dr. Nascimento was supported by the Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) fellowship [236608/2013-4].

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qvarnstrom, Y., Wei-Pridgeon, Y., Van Roey, E. et al. Purification of Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts obtained from human stool specimens for whole genome sequencing. Gut Pathog 10, 45 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-018-0272-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-018-0272-7