Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common complication of pregnancy. The disease is on the rise worldwide with deleterious consequences on the fetus, mother, and children. The study aimed to review the role of lifestyle in the prevention of GDM. We searched PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EBSCO, and Google Scholar from the first published article up to December 2021; articles were eligible if they were controlled trials, prospective cohorts, and case–control. Out of 5559 articles retrieved, 66 full texts were screened, and 19 studies were included in the meta-analysis. (6 studies assessed the effects of diet, and 13 were on exercise). The dietary intervention showed significant positive effect on GDM, odd ratio = 0.69, 95% CI, 0.56–84, P-value for overall effect = 0.002. The DASH diet was better than Mediterranean Diet (odd ratio, 0.71, 95% CI, 68–74, P-value < 0.001). Regarding exercise, no significant prevention was evident on GDM, odd ratio, 0.77, 95% CI, 0.55–1.06, P-value = 0.11. However, a significant prevention of gestational diabetes was found when the exercise was mild-moderate (odd ratio = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.53–80, P < 0.0001) and started in the first trimester (odd ratio, 0.57, 95% CI, 0.43–0.75, P < 0.0001. No significant effect was found when the exercise was vigorous (odd ratio = 1.09, 95% CI, 0.50–2.38, P = 0.83) and started during the second trimester of pregnancy (odd ratio, 1.08, 95% CI, 0.65–1.80, P = 0.77. Diet and early mild-moderate exercise were effective in GDM prevention. Exercise during the second trimester and moderate-vigorous were not. Further studies assessing the type, duration, and frequency of physical activity are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common medical complication of pregnancy, it affects 5–6% of pregnant women in the USA according to the Carpenter-Coustan criteria, and the rate would increase to 15–20% when the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups criteria is applied. GDM is on the rise due to increasing age and obesity [1]. The rate of obesity and overweight is rapidly increasing globally and in particular, for the Gulf countries including the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, this is mirrored by the high prevalence of obesity-related disorders including diabetes [2]. Diabetes mellitus is more prevalent among Saudi females mainly due to an unfriendly diet. The rapid development in Saudi Arabia substantially shifted the diet from the healthy traditional diet to a more Westernized diet with deleterious consequences [3]. GDM increases both maternal and fetal complications including excess fetal growth, cardiovascular disease, impaired glucose metabolism, and pregnancy-related hypertensive disease. Physical activity and dietary modifications are the mainstay of management with insulin, Glyburide, and metformin used when normoglycemia is not achieved [4]. Lifestyle modifications need great effort from both the healthcare professionals and the patients and are usually faced with numerous barriers that may lead to poor glycemic control [5]. The role of lifestyle in the prevention of GDM is a matter of controversy. The available evidence regarding the lifestyle modification effects on GDM is weak due to the different diets included; furthermore, no single diet fits all. Mediterranean diet is the only diet that is recommended to patients with diabetes mellitus [6]. Besides, both diet and exercise might be affected by the type, timing, and amount (exercise is also affected by the duration). In addition, non-adherence is a substantial factor compromising the quality of studies [7]. Individual food items were extensively studied, but nutrients are not consumed in isolation either they are consumed in different combinations (dietary patterns). In addition, dietary patterns mimic real-world scenarios and can be translated into simple and easy-to-follow recommendations. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet (AHEI), and Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) were shown to reduce diabetes, mortality, and cardiovascular disease. However, their effects on gestational diabetes prevention are scarce [8,9,10,11]. Tobias and colleagues in their retrospective cohort showed that aHEI lowered the risk of GDM by 46%, followed by the DASH diet (34%), and MedDiet (24%) [12]. The previous observation was supported by another study (57%, 46%, and 40% reduction in aHEI diet, DASH diet, and MedDiet respectively) [13]. Another study showed a higher reduction in GDM among patients adherent to MedDiert compared to the DASH diet (80% vs. 71%) [14] A randomized trial supported the above observations and showed the beneficial effects of the DASH diet on glycemic and lipid parameters [15]. Further randomized controlled trials showed the beneficial effects of the DASH diet on insulin resistance and glycemic parameters [16]. To the best of our knowledge, no review compared different dietary patterns in the prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus. Therefore, the current review assessed the effects of MedDiet, DASH diet, and aAEI diet on the prevention of gestational diabetes and assessed if one diet is superior. In addition, this meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of exercise (throughout, first and second trimester).

Methods

Articles selection according to PICOS

We searched PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EBSCO, and the first 100 articles in Google Scholar from the first published article up to December 2021, articles were eligible if they were controlled trials, prospective cohorts, and case–control studies and published in English. Article in languages other than English, other methodologies (case series, and case reports were not included. The trials must fulfill the following outcomes to be included:

-

The effect of the Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet (AHEI) on GDM prevention

-

The effect of first and second-trimester exercise on GDM prevention.

We excluded diabetes mellitus prevention programs carried on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or women with established GDM.

Literature search and data extraction

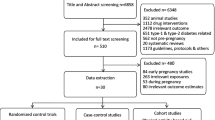

The two authors (A.H, and R.A) searched the mentioned databases for relevant articles, out of 5559 articles retrieved, 66 full texts were screened, and 19 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Fig. 1. In the current review, 6 studies assessed the effects of diet, and 13 were on exercise. Of them, eight assessed exercises in the first trimester and five in the second trimester. We did not specify any criteria for GDM diagnosis due to the different methods that might be applied during the long period of the search engine. The retrieved data were exported to an excel sheet detailing the author's names, country of origin of the study, the number of patients and control subjects, and the total number of events in the interventional and exercise groups (Tables 1 , 2). The details of exercise including the type, duration, and intensity, the diet type, and the compliance when reported were also recorded. In this review we concentrated on dietary habits and detailed exercise (timing and duration). Tables 3 ,4 and Fig. 1.

Quality assessment of the cited trials

The quality of the included studies was assessed using a modified Cochrane risk of bias. Table 5.

Data analysis

We use RevMan (version 5, 4) for data analysis, the data were entered manually, and dichotomous variables were compared. The fixed effect was applied unless a significant heterogeneity (> 50%) was observed. A P-value of 0.05 is significant except when a significant heterogeneity.

Ethical consideration

We did not include studies published by the authors.

Results

The dietary intervention included three studies [18, 19] with significant positive effect on GDM, odd ratio = 0.69, 95% CI, 0.56–84, P-value for overall effect = 0.002, with no significant heterogeneity, I2 = 0.0%. Fig. 2.

The DASH diet showed superiority to MedDiet Mediterranean Diet [13,14,15] (odd ratio, 0.71, 95% CI, 68–74, P-value < 0.001). Furthermore, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet was better than the DASH diet (odd ratio, 0.69, 95% CI, 53–91, P-value, 0.008). Fig. 3 and 4.

Regarding exercise, there were thirteen studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] with no significant prevention on GDM (total patients 4202 and 418 events), odd ratio, 0.77, 95% CI, 0.55–1.06, P-value for overall effect = 0.11, with significant heterogeneity, I.2 = 62% and P-value for heterogeneity, 0.002. Fig. 5

However, when a sub-analysis was conducted, significant prevention of gestational diabetes was found when the exercise started in the first trimester (odd ratio, 0.57, 95% CI, 0.43–0.75, P-value for overall effect < 0.0001, with significant heterogeneity, I2 = 40%. Fig. 6.

No significant effect was found when the exercise started during the second trimester of pregnancy [22, 25, 26, 28, 30] (odd ratio, 1.08, 95% CI, 0.65–1.80, P-value for overall effect = 0.77, with significant heterogeneity, I2 = 51%. Fig. 7.

It is interesting to note that mild-moderate intensity exercise was effective in gestational diabetes prevention (odd ratio = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.53–80, P-value for overall effect < 0.0001, with significant heterogeneity, I2 = 36.0%. Fig. 8), while vigorous activity was not (odd ratio = 1.09, 95% CI, 0.50–2.38, P-value for overall effect = 0.83, with no significant heterogeneity, I2 = 51.0%. Fig. 9).

Discussion

The present meta-analysis showed that diet was effective in gestational diabetes prevention, while exercise was not. However, a sub-analysis showed that exercise was effective only when introduced in the first trimester; physical activity started in the second trimester was not effective. In addition, mild-moderate exercise was effective in contrast to vigorous physical activity. Previous studies with a low quality of evidence showed the efficacy of combined diet and exercise [33, 34]. The meta-analyses lack a face-to-face comparison between different forms of diets. In addition, they did not report the timing and intensity of exercise. Another study showed similar results but only among obese women [35]. Dietary supplementation with myo-inositol reduced GDM in a study that included four trials and lacked generalization [36].

Special types of diets

Alternate healthy eating index-2010

The AHEI-2010 is a measure of diet quality based on food items predictive of major chronic disease risk, particularly cardiometabolic disease including stroke and diabetes, and malignancies. It emphasizes a high intake of legumes and nuts, cereals, vegetables and fruits, omega-3 fats, and polyunsaturated fatty acids while limiting the intake of red and processed meats, sodium, sugary beverages, and alcohol [37].

The effect of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 in reducing GDM ranged from 19–46%, interestingly, when the diet is combined with other risk factors reduction (physical activity, smoking, and normal body weight) the risk reduction may be as high as 83% [38]. A 41% lower risk of gestational diabetes was observed among patients adherent to aHEI [39]. A genetic interaction increases the like hood of developing GDM among patients on aHEI diet [40]. In addition, health education and self-efficacy substantially improved the quality of aHEI [41], the included studies showed that Alternate Healthy Eating Index is superior compared to the DASH diet and MedDiet [13,14,15].

Mediterranean diet (MedDiet)

The Mediterranean diet is a diet with high fruits and vegetables, bread, legumes, olive oil, cereals, fish, and limited animal products [42].

The Mediterranean diet is promising for the prevention of GDM, however, the results are contradictory. A recent meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trial showed the efficacy of MedDiet in preventing GDM [43]. A recent review examined the role of MedDiet in modulating immune response and inflammation during COVID-19 and showed that MedDiet reduced interleukin-6 and inflammatory markers [44]. A recent case–control study showed that MedDiet reduced GDM incidence [45], interestingly, women who have rs7903146 T-allele showed a high reduction of GDM compared to their counterparts who are not indicating a gene-diet interaction [46]. The protective effect of MedDiet ranged from 15 to 38% depending on compliance, genetic factors, and the diagnostic method used (8% when the American Diabetes Association was used and 24% If The International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups was used [38]. Although MedDiet was effective in preventing gestational diabetes mellitus, DASH diet and aAEI showed superiority [13,14,15].

Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH)

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) originally developed for hypertension consists of high intakes of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts, moderate low-fat dairy products, and low consumption of sodium, animal protein, and sweets [47], of the three studies investigating the effects of the DASH diet on gestational diabetes showed superiority when compared to MedDiet. However, the DASH diet was inferior to Alternate Healthy Eating Index [13,14,15].

Western and prudent diet

Zhang and colleagues found a positive association between Western and a negative association of prudent diet with GDM risk, while Radesky et al. found no associations. [48, 49].

Physical activity

In the present study, exercise was effective in the first trimester and not during the second trimester; previous studies showed lifestyle before gestation was effective in reducing diabetes. However, exercise during pregnancy was not [50]. Other studies showed early pregnancy (before the 15th week) lifestyles were effective [51] in line with our findings. The effect of physical activity on GDM prevention depends on the time and duration of physical activity. Exercise before or in early pregnancy was effective in reducing GDM in the majority of studies [52,53,54,55], while few studies showed no significant reduction. [56, 57]. A leisure time of physical activity of 150 h/week before pregnancy was associated with 68% risk reduction, and the benefits increased with longer duration [57].

Davenport and colleagues found that exercise of moderate intensity is effective in the prevention of GDM when adopted prenatally in line with our findings [58], the same conclusion was shown by other studies [59]. Davenport et al. study was limited by including all types of articles except case studies. A meta-analysis from China showed that diet and exercise were effective in reducing GDM when introduced earlier (before the 15th week), an effect that was not robot after that [51]. Other studies published in Spain and Australia [9, 60] and concluded the effectiveness of dietary advice and moderate exercise combination in GDM prevention in contradiction to the present result, a plausible explanation might be the different methods of exercise and the type of diet adopted. The earlier adoption of 50–60 min of moderate physical activity and targeting at-risk women with a high body mass index was found to be more effective [61]. However, an update of the same study showed a limited ability to inform practice due to the risk of bias observed in the included studies [62]. Further studies limited by including retrospective, cross-sectional, and case–control studies support the above findings regarding exercise [63]. We found only one meta-analysis assessing the effect of early and late exercise on GDM. However, the small number of included studies and the high heterogeneity limited the studies [64]. The study found no effect throughout pregnancy. A non-linear negative association between exercise before and during early pregnancy was observed by the previous literature. The association was steeper at lower levels; however, the benefits plateaued at 8–10 h a week, a finding that may explain the contradiction between various studies assessing the effects of exercise on GDM [24]. The compliance to exercise, duration, timing, and type of exercise might greatly influence the outcomes. To best inform Obstetric guidelines, studies putting the previous parameters into consideration are warranted.

The strength of the current meta-analysis is that it is the first to compare different types of diets and define the time, intensity, duration, and frequency of exercise.

Limitations

The study limitations were including some observational studies, the limitations to the English language, and the significant heterogeneity observed.

Conclusion

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet, and Mediterranean Diet were effective in reducing gestational diabetes mellitus. The DASH diet showed superiority to the Mediterranean. Furthermore, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet was better than the DASH diet. Data regarding physical activity were conflicting. Early mild-moderate physical activity was effective, while late, moderate-vigorous exercise was not. Randomized control trials and genetic studies are needed for the individualization of dietary patterns.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this manuscript are available upon request.

Abbreviations

- MedDiet:

-

Mediterranean diet

- DASH diet:

-

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- AHEI:

-

Alternate Healthy Eating Index diet

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

References

Hod M, Kapur A, McIntyre HD, FIGO Working Group on Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy, FIGO Pregnancy and Prevention of early NCD Committee. Evidence in support of the international association of diabetes in pregnancy study groups’ criteria for diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus worldwide in 2019. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):109–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.206.

DeNicola E, Aburizaiza OS, Siddique A, Khwaja H, Carpenter DO. Obesity and public health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(3):191–205. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2015-0008.

Washi SA, Ageib MB. Poor diet quality and food habits are related to impaired nutritional status in 13- to 18-year-old adolescents in Jeddah. Nutr Res. 2010;30(8):527–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2010.07.002.

McIntyre HD, Catalano P, Zhang C, Desoye G, Mathiesen ER, Damm P. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0098-8.

Martis R, Brown J, McAra-Couper J, Crowther CA. Enablers and barriers for women with gestational diabetes mellitus to achieve optimal glycaemic control—a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1710-8.

American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S111–34. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S010.

Parra DI, Romero Guevara SL, Rojas LZ. Influential factors in adherence to the therapeutic regime in hypertension and diabetes. Invest Educ Enferm. 2019. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v37n3e02.

Morze J, Danielewicz A, Hoffmann G, Schwingshackl L. Diet Quality as assessed by the healthy eating index, alternate healthy eating index, dietary approaches to stop hypertension score, and health outcomes: a second update of a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(12):1998-2031.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2020.08.076.

Mijatovic-Vukas J, Capling L, Cheng S, Stamatakis E, Louie J, Cheung NW, et al. Associations of diet and physical activity with risk for gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060698.

Li S, Gan Y, Chen M, Wang M, Wang X, Santos O, H, et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) on pregnancy/neonatal outcomes and maternal glycemic control a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2020;54:102551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102551.

Shan Z, Li Y, Baden MY, Bhupathiraju SN, Wang DD, Sun Q, et al. Association between healthy eating patterns and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1090–100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2176.

Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142:1009–18.

Tobias DK, Zhang C, Chavarro J, Bowers K, Rich-Edwards J, Rosner B, et al. Prepregnancy adherence to dietary patterns and lower risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(2):289–95. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.028266.

Tobias DK, Hu FB, Chavarro J, Rosner B, Mozaffarian D, Zhang C. Healthful dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1566–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3747.

Izadi V, Tehrani H, Haghighatdoost F, Dehghan A, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. Adherence to the DASH and Mediterranean diets is associated with decreased risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutrition. 2016;32(10):1092–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2016.03.006.

Asemi Z, Tabassi Z, Samimi M, Fahiminejad T, Esmaillzadeh A. Favourable effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet on glucose tolerance and lipid profiles in gestational diabetes: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(11):2024–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512004242.

Assaf-Balut C, García de la Torre N, Durán A, et al. A Mediterranean diet with additional extra virgin olive oil and pistachios reduces the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): a randomized controlled trial The St. Carlos GDM prevention study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0185873.

Al Wattar H, Dodds J, Placzek A, et al. Mediterranean-style diet in pregnant women with metabolic risk factors (ESTEEM): a pragmatic multicentrerandomised trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(7):e1002857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002857.

Sahariah SA, Potdar RD, Gandhi M, et al. A daily snack containing leafy green vegetables, fruit, and milk before and during pregnancy prevents gestational diabetes in a randomized, controlled trial in Mumbai. India J Nutr. 2016;146(7):1453S-S1460. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.223461.

Barakat R, Refoyo I, Coteron J, Franco E. Exercise during pregnancy has a preventative effect on excessive maternal weight gain and gestational diabetes. A randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019;23(2):148–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.11.005.

Cordero Y, Mottola MF, Vargas J, Blanco M, Barakat R. Exercise is associated with a reduction in gestational diabetes mellitus. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(7):1328–33. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000547.

da Silva SG, Hallal PC, Domingues MR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes: results from the PAMELA study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0632-6.

Daly N, Farren M, McKeating A, O’Kelly R, Stapleton M, Turner MJ. A medically supervised pregnancy exercise intervention in obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):1001–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002267.

Callaway LK, Colditz PB, Byrne NM, Lingwood BE, Rowlands IJ, Fox K, et al. Prevention of gestational diabetes: feasibility issues for an exercise intervention in obese pregnant women. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1457–9.

Nobles C, Marcus BH, Stanek EJ 3rd, et al. Effect of an exercise intervention on gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1195–204. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000738.

Oostdam N, Van Poppel M, Wouters M, Eekhof E, Bekedam D, Kuchenbecker W, et al. No efect of the FitFor2 exercise programme on blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, and birthweight in pregnant women who were overweight and at risk for gestational diabetes: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119(9):1098–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03366.x.

Ruiz JR, Perales M, Pelaez M, Lopez C, Lucia A, Barakat R. Supervised exercise-based intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1388–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.07.020.

Seneviratne SN, Jiang Y, Derraik J, McCowan L, Parry GK, Biggs JB, et al. Effects of antenatal exercise in overweight and obese pregnant women on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2016;123(4):588–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13738.

Simmons D, Devlieger R, van Assche A, Jans G, Galjaard S, Corcoy R, et al. Effect of physical activity and/or healthy eating on GDM risk: the DALI lifestyle study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):903–13. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-3455.

Stafne SN, Salvesen KÅ, Romundstad PR, Eggebø TM, Carlsen SM, Mørkved S. Regular exercise during pregnancy to prevent gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182393f86.

Tomić V, Sporiš G, Tomić J, Milanović Z, Zigmundovac-Klaić D, Pantelić S. The effect of maternal exercise during pregnancy on abnormal fetal growth. Croat Med J. 2013;54(4):362–8. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2013.54.362.

Wang C, Wei Y, Zhang X, et al. A randomized clinical trial of exercise during pregnancy to prevent gestational diabetes mellitus and improve pregnancy outcome in overweight and obese pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(4):340–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.037.

Bain E, Crane M, Tieu J, Han S, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Diet and exercise interventions for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD010443. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010443.pub2.

Tieu J, Shepherd E, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Dietary advice interventions in pregnancy for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1(1):CD006674. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006674.pub3.

Rogozińska E, Chamillard M, Hitman GA, Khan KS, Thangaratinam S. Nutritional manipulation for the primary prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised studies. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2): e0115526. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115526.

Crawford TJ, Crowther CA, Alsweiler J, Brown J. Antenatal dietary supplementation with myo-inositol in women during pregnancy for preventing gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):CD011507. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011507.pub2.

Estrella ML, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Mattei J, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Perreira KM, Siega-Riz AM, et al. Alternate healthy eating index is positively associated with cognitive function among middle-aged and older Hispanics/Latinos in the HCHS/SOL. J Nutr. 2020;150(6):1478–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa023.

Asemi Z, Samimi M, Tabassi Z, Sabihi SS, Esmaillzadeh A. A randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of DASH diet on insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes. Nutrition. 2013;29(4):619–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2012.11.020.

Zhang C, Tobias DK, Chavarro JE, Bao W, Wang D, Ley SH, et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;30(349): g5450. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5450.

Li M, Rahman ML, Wu J, Ding M, Chavarro JE, Lin Y, et al. Genetic factors and risk of type 2 diabetes among women with a history of gestational diabetes: findings from two independent populations. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1): e000850. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000850.

Ferranti EP, Narayan KM, Reilly CM, Foster J, McCullough M, Ziegler TR, et al. Dietary self-efficacy predicts AHEI diet quality in women with previous gestational diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(5):688–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714539735.

Zhang Y, Xia M, Weng S, Wang C, Yuan P, Tang S. Effect of Mediterranean diet for pregnant women: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;25:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1868429.

Fedullo AL, Schiattarella A, Morlando M, Raguzzini A, Toti E, De Franciscis P, et al. Mediterranean diet for the prevention of gestational diabetes in the Covid-19 Era: implications of Il-6 in diabesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031213.

Mahjoub F, Ben Jemaa H, Ben Sabeh F, Ben Amor N, Gamoudi A, Jamoussi H. Impact of nutrients and Mediterranean diet on the occurrence of gestational diabetes. Libyan J Med. 2021;16(1):1930346. https://doi.org/10.1080/19932820.2021.1930346.

Barabash A, Valerio JD, Garcia de la Torre N, Jimenez I, Del Valle L, Melero V, et al. TCF7L2 rs7903146 polymorphism modulates the association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Metabol Open. 2020;8:100069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metop.2020.100069.

Karamanos B, Thanopoulou A, Anastasiou E, Assaad-Khalil S, Albache N, Bachaoui M, MGSD-GDM Study Group, et al. Relation of the Mediterranean diet with the incidence of gestational diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(1):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.177.

Li S, Zhu Y, Chavarro JE, Bao W, Tobias DK, Ley SH, et al. Healthful dietary patterns and the risk of hypertension among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Hypertension. 2016;67(6):1157–65. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06747.

Zhang C, Schulze MB, Solomon CG, Hu FB. A prospective study of dietary patterns, meat intake and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2006;49(11):2604–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0422-1.

Radesky JS, Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Diet during early pregnancy and development of gestational diabetes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00899.x.

Li N, Yang Y, Cui D, Li C, Ma RCW, Li J, et al. Effects of lifestyle intervention on long-term risk of diabetes in women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2021;22(1): e13122. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13122.

Song C, Li J, Leng J, Ma RC, Yang X. Lifestyle intervention can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2016;17(10):960–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12442.

Zhang C, Solomon CG, Manson JE, Hu FB. A prospective study of pregravid physical activity and sedentary behaviors in relation to the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):543–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.5.543.

Badon SE, Wartko PD, Qiu C, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Enquobahrie DA. Leisure time physical activity and gestational diabetes mellitus in the omega study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1044–52. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000866.

Dempsey JC, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, Miller RS, Dashow EE, et al. Prospective study of gestational diabetes mellitus risk in relation to maternal recreational physical activity before and during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):663–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh091.

Mørkrid K, Jenum AK, Berntsen S, Sletner L, Richardsen KR, Vangen S, et al. Objectively recorded physical activity and the association with gestational diabetes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(5):e389–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12183.

Currie LM, Woolcott CG, Fell DB, Armson BA, Dodds L. The association between physical activity and maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(8):1823–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1426-3.

van der Ploeg HP, van Poppel MN, Chey T, Bauman AE, Brown WJ. The role of pre-pregnancy physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(2):149–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2010.09.002.

Davenport MH, Ruchat SM, Poitras VJ, Jaramillo Garcia A, Gray CE, Barrowman N, et al. Prenatal exercise for the prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(21):1367–75. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099355.

Shepherd E, Gomersall JC, Tieu J, Han S, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Combined diet and exercise interventions for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11(11):CD010443. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010443.pub3.

Sanabria-Martínez G, García-Hermoso A, Poyatos-León R, Álvarez-Bueno C, Sánchez-López M, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on preventing gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive maternal weight gain: a meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;122(9):1167–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13429.

Guo XY, Shu J, Fu XH, Chen XP, Zhang L, Ji MX, et al. Improving the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for gestational diabetes prevention: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. BJOG. 2019;126(3):311–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.

Han S, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Exercise for pregnant women for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11(7):CD009021. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009021.pub2.

Aune D, Sen A, Henriksen T, Saugstad OD, Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(10):967–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0176-0.

Nasiri-Amiri F, Sepidarkish M, Shirvani MA, Habibipour P, Tabari NSM. The effect of exercise on the prevention of gestational diabetes in obese and overweight pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;27(11):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-019-0470-6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support for this work from the Deanship of Scientific Research, University of Tabuk, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia. Grant No. S-0097-1439.

Funding

This study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, University of Tabuk, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia under the grant No. (S-0097-1439).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: AHA & RAA. Literature search: AHA & RAA. Data analysis: AHA. Manuscript drafting, revision, and before submission: AHA & RAA. Manuscript submission: AHA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

We did not include any article published by the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Altemani, A.H., Alzaheb, R.A. The prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus (The role of lifestyle): a meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr 14, 83 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00854-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00854-5