Abstract

Background

Chloride is a key electrolyte that regulates the body fluid distribution. Accordingly, manipulating chloride kinetics by selecting a suitable diuretic could be an attractive strategy for correcting body fluid dysregulation. Therefore, this study examined the effects and contributing factors of a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) on the serum chloride concentration in type 2 diabetic (T2DM) patients without heart failure (HF).

Methods

This study was a retrospective single-center observational study that enrolled 10 T2DM/non-HF outpatients for whom the SGLT2i empagliflozin (daily oral dose of 10 mg) was prescribed. Among these 10 patients, 6 underwent detailed clinical testing that included hormonal and metabolic blood tests.

Results

Empagliflozin treatment for 1–2 months decreased body weight (− 2.69 ± 1.9 kg; p = 0.002) and HbA1c (− 0.88 ± 0.55%; p = 0.0007). The hemoglobin (+ 0.27 ± 0.36 g/dL; p = 0.04) and hematocrit (+ 1.34 ± 1.38%; p = 0.014) values increased, but the serum creatinine concentration remained unchanged. The serum chloride concentration increased from 104 ± 3.23 to 106 ± 2.80 mEq/L (p = 0.004), but the sodium and potassium concentrations did not change. The spot urinary sodium concentration decreased from 159 ± 43 to 98 ± 35 mEq/L (p < 0.02) and the spot urinary chloride tended to decrease (from 162 ± 59 to 104 ± 36 mEq/L, p < 0.08). Both renin and aldosterone tended to be activated (5/6, 83%). The strong organic acid metabolite concentrations of serum acetoacetate (from 42 ± 25 to 100 ± 45 μmol/L, p < 0.02) and total ketone bodies (from 112 ± 64 to 300 ± 177 μmol/L, p < 0.04) increased, but the actual HCO3− concentration decreased (from 27 ± 2.5 to 24 ± 1.6 mEq/L, p < 0.008).

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that SGLT2i enhances the serum chloride concentration in T2DM patients and suggests that the effect is mediated by the possible following mechanisms: (1) enhanced reabsorption of urinary chloride by aldosterone activation due to blood pressure lowering and blood vessel contraction effects, (2) reciprocal increase in the serum chloride concentration by reducing the serum HCO3− concentration via a buffering effect of strong organic acid metabolites, and (3) reduced NaHCO3 reabsorption and concurrently enhanced chloride reabsorption in the urinary tubules by inhibiting Na+–H+ exchanger 3 in the renal proximal tubules. Thus, the diuretic SGLT2i induces excessive extravascular fluid to drain into the vascular space by the enhanced vascular “tonicity” caused by the elevated serum chloride concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes mellitus is a worldwide public health and economic problem. Glucose-regulating drug of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) may offer unique benefits as glucose-lowering agent [1,2,3]. Importantly, SGLT2i appear to have pleotropic effects [1,2,3] that are also cardioprotective and renal protective in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [4,5,6], and are now widely approved as antihyperglycemic agents.

Recent studies demonstrated that chloride is a key electrolyte for regulating plasma volume during worsening heart failure (HF) [7] and its recovery [8], leading to the development of the “chloride theory” for HF pathophysiology [9, 10] and a diuretic treatment strategy by modulating the serum chloride concentration [10, 11]. According to the “chloride theory” [10], dysregulated body fluid distribution can be adjusted by manipulating the serum chloride concentration using a suitable diuretic. SGLT2i is reported to exert diuresis through osmotic and natriuretic effects that contribute to plasma contraction and decrease blood pressure [1,2,3]. There is a paucity of data, however, regarding the effects of this agent on the serum chloride concentration, and even less is known about its precise diuretic mechanisms. Therefore, this study investigated the effects and possible underlying mechanisms of diuretic of an SGLT2i on the serum chloride concentration and its clinical significance according to the “chloride theory” [10] in T2DM/non-HF patients.

Methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective single-center observational study that enrolled outpatients with T2DM/non-HF at Nishida Hospital (Saiki-city, Oita, Japan) prescribed empagliflozin (daily oral dose of 10 mg) between March 2017 and April 2018. The effects of empagliflozin on the serum chloride concentration were evaluated 1 to 2 months after administration was initiated. During the study period, empagliflozin was prescribed to 20 T2DM/non-HF patients, but 10 patients were excluded from the present study due to the lack of required clinical data (n = 6), complications with a serious co-morbidity requiring hospitalization (n = 2), or use of a diuretic (n = 2). The 10 remaining clinically stable T2DM/non-HF patients were the subjects analyzed in the present study. Among these 10 patients, 6 underwent detailed clinical examinations, including hormonal and metabolic blood tests, to estimate the factors contributing to the SGLT2i-mediated modulation of the serum chloride concentration. None of the patients enrolled in the study had used diuretics other than SGLT2i either before the initiation of SGLT2i administration or throughout the study period of SGLT2i treatment evaluation.

The ethics committee at Nishida Hospital approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study enrollment.

Data collection and analytic methods

Physical examination, blood tests of peripheral venous blood (hematologic, diabetic/metabolic, b-type natriuretic peptide, venous blood gas, and neurohormonal tests), and a spot urine test for electrolytes were performed at baseline and 1 to 2 months after beginning SGLT2i administration. The blood samples were obtained after patients rested in a supine position for 20-min. Peripheral blood tests, analyzed by standard techniques, included a red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean red blood cell volume, albumin, serum and urinary electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and chloride), blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine. The spot urine test included measurement of electrolyte concentrations. Hemoglobin A1c (%) was determined by high performance liquid chromatography. Plasma b-type natriuretic peptide was measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay. Plasma renin activity was measured by enzyme immunoassay. Aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone levels were measured by radioimmunoassay. Plasma acetoacetate, 3-hydroxybutyrate, and total ketone body concentrations were measured by the enzyme cycling method. Total CO2, actual HCO3−, and pO2 were analyzed using an ABL80 FLEX autoanalyzer (Radiometer Medical ApS, Brφnshφj, Denmark).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (San Diego, CA). All data are expressed as the mean ± SD for continuous data and percentage for categorical data. Paired t tests for continuous data were used for two-group comparisons. All tests were 2-tailed, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the 10 T2DM/non-HF patients at study entry are shown in Table 1. Mean patient age was 61.7 ± 14 years (range, 36–92 years), and 40% were men. Cardiac function and renal function were preserved in all study patients, determined mainly on the basis of the b-type natriuretic level and estimated glomerular filtration rate. One patient had a history of myocardial infarction. None of the patients were on diuretics. Therapy for diabetes included isolated or combined use of metformin, sulfonylureas, and/or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.

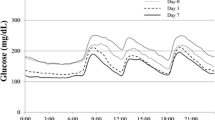

SGLT2i treatment details for the six study patients are presented in Table 2. After 1 to 2 months (34.9 ± 7.4 [range 28–53] days) of empagliflozin administration, body weight (− 2.69 ± 1.9 [range, − 6.1 to − 0.2] kg; p = 0.002) and hemoglobin A1c (− 0.88 ± 0.55 [range, − 1.8 to − 0.2]%; p = 0.0007) decreased. Serum b-type natriuretic peptide levels did not change. Hemoglobin (+0.27 ± 0.36 [range, − 0.5 to +0.8] g/dL; p = 0.04) and hematocrit (+ 1.34 ± 1.38 [range, − 0.7 to +4.1]%; p = 0.014) increased, but the serum creatinine concentration was unchanged. The serum chloride concentration increased from 104 ± 3.23 to 106 ± 2.80 mEq/L with a mean change of 2.1 ± 1.7 mEq/L (range, − 1 to + 5 mEq/L; p = 0.004), but the serum sodium and potassium concentrations did not change. The spot urine test revealed that the sodium concentration decreased (from 159 ± 43 to 98 ± 35 mEq/L, p < 0.02) and the chloride concentration tended to decrease (from 162 ± 59 to 104 ± 36 mEq/L, p < 0.08). Both renin and aldosterone tended to be activated (5/6 patients, 83%). Serum levels of strong organic acid metabolites of acetoacetate (+ 57.8 ± 38.5 μmol/L; range, + 7 to + 107 μmol/L; p < 0.02) and total ketone bodies (+ 188 ± 167 μmol/L; range, − 17 to + 470 μmol/L; p < 0.04) increased, but the serum levels of actual HCO3− decreased (− 2.5 ± 1.4 mEq/L; range, − 4.2 to − 0.8 mEq/L; p < 0.008).

Discussion

Diabetic patients frequently present with electrolyte abnormalities [12]. The diuretic effects of SGLT2i may influence the serum chloride concentration, but few experimental [13,14,15] and clinical studies [16, 17] have deeply evaluated the effects and mechanistic consideration of SGLT2i on the serum chloride levels. The findings of the present study indicate that SGLT2i preserves or enhances the serum chloride concentration in T2DM/non-HF patients. Finding of regaining the serum chloride concentration under dosage of SGLT2i in the present study accords with the recent experimental studies [13,14,15]. Other findings of physical, hematologic, diabetic/metabolic, and neurohormonal tests were consistent with previous observations [1,2,3].

Role of chloride and contribution of SGLT2i in regulating body fluid distribution

After sodium, chloride is the most abundant serum electrolyte [18], with a key role in the regulation of body fluids, electrolyte balance, preservation of electrolyte neutrality, and acid–base status, and is the essential component for assessing many pathologic conditions [19]. Recent studies [7,8,9,10,11] indicate that chloride, not sodium, is the primary electrolyte for regulating the fluid distribution in the human body according to the possible biochemical nature of the solutes, as follows. Solutes in the human body are classified as effective or ineffective osmoles on the basis of their ability to generate osmotic water movement, and osmotic water flux requires a solute concentration gradient [18]. “Tonicity” is the effective osmolality across a barrier, and regulates body water distribution to each body space compartment. According to the “chloride theory” [10], chloride ions, not sodium ions, are the key electrolyte for regulating the plasma volume in the human body. Thus, compared with cationic sodium ions, anionic chloride ions in the human body have the potential for “tonicity” in the vascular space [8, 10]; namely, chloride ions are the key electrolytes for primary regulation of the distribution of body fluid across body spaces, i.e., the intracellular, intravascular, interstitial compartments [18], and the pleural space [20].

As such, the present study demonstrated that SGLT2i could be classified as a “chloride-regaining” diuretic [10], such as acetazolamide [11, 21, 22] or vasopressin antagonists [23, 24]. “Chloride-regaining” diuretics, defined by the “chloride theory” [10], could have peculiar properties of preserving plasma volume and renal function [22, 25, 26], and the capability of draining interstitial body fluid by the serum chloride-associated enhancement of vascular “tonicity” [8, 10], as mentioned above. This concept is consistent with the recent clinical observations that SGLT2i reduces interstitial congestion without deleterious effects of arterial underfilling or predominantly decreased extracellular volume [27, 28].

Underlying mechanisms of SGLT2i for regaining the serum chloride concentration

It is reasonable to consider that the increase in serum chloride concentration by the administration of SGLT2i is caused by its osmotic diuretic action with subsequent water excretion (aquaresis) and mild hemoconcentration, mechanisms similar to those of vasopressin antagonists [23, 24]. In addition, the findings of the present study suggest the following underlying mechanisms for regaining or enhancing the serum chloride concentration. First, reabsorption of urinary chloride is enhanced by activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) induced by SGLT2i due to blood pressure-lowering and blood vessel-contracting effects. Activation of the RAAS might be also induced by the reduced chloride supply to the macula densa by SGLT2 inhibition, similar to the actions of loop diuretics [29]. Controversies exist, however, about the effects of the SGLT2i on RAAS activity [30]. Indeed, a previous report pointed out that SGLT2i therapy inhibits RAAS activity [31]. It is likely that various levels of RAAS activity are observed in different phases (e.g., acute, sub-acute, or chronic) of SGLT2i treatment among heterogeneous T2DM patients [32]. The “chloride theory” [10] predicts that SGLT2i likely inhibits RAAS activity by its chloride-regaining effects [33]. In the present study, the RAAS activity at baseline was already slightly activated similar to a previous report [34], but RAAS activation was not markedly activated after SGLT2i treatment.

Second, it could be expected that a reciprocal increase in the serum chloride concentration might be caused by reducing the serum HCO3− concentration [35] by buffering [36, 37] strong organic acid metabolites (e.g., ketone bodies of acetoacetic acid and 3-hydroxybutyric acid in the present study) under SGLT2i treatment [38, 39]. Lastly, inhibitory effects of SGLT2i on Na+–H+ exchanger 3 in the renal proximal tubules might reduce NaHCO3 reabsorption and concurrently enhance chloride reabsorption in the urinary tubules [40, 41]. According to these possible mechanisms, SGLT2i has a potential to preserve or enhance the serum chloride concentration. The precise mechanisms of SGLT2i for preserving the serum chloride concentration, however, require further exploration.

Limitations

This study included a small number of patients at a single center, and there are important limitations to consider, including (1) a selection bias due to data availability and (2) low statistical power with wide variabilities in the data. Thus, the data must be cautiously interpreted. To my knowledge, however, it is the first study examined the effects and contributing factors of SGLT2i on the serum chloride concentration in T2DM/non-HF patients. Additional studies with more T2DM patients with or without HF, and an extended observational period are needed to better clarify the diuretic effects of SGLT2i on the chloride kinetics.

Conclusions

An SGLT2i administration in T2DM/non-HF patients preserve or enhance the serum chloride concentration. Such a diuretic effect would preserve vascular volume and promote drainage of excessive extravascular fluid into the vascular space [27, 28] by enhancing vascular “tonicity” [8]. Caution is advised when using an SGLT2i in patients with hypernatremia/chloremia because these diuretics might lead to an increase in serum chloride and sodium levels [42].

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable. Conclusions of the manuscript are based on relevant data sets available in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HF:

-

heart failure

- RAAS:

-

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- SGLT2i:

-

sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

- T2DM:

-

type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

Lambers Heerspink HJ, de Zeeuw D, Wie L, Leslie B, List J. Dapagliflozin a glucose-regulating drug with diuretic properties in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:853–62.

Lambers Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZ. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation. 2016;134:752–72.

Vallon V, Thomson SC. Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia. 2017;60:215–25.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE, EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117–28.

Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Zinman B. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–34.

Fitchett D, Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Hantel S, Salsali A, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedle UC, Inzucchi SE, on behalf of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial investigators. Heart failure outcomes with empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: results of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1526–34.

Kataoka H. Vascular expansion during worsening of heart failure: effects on clinical features and its determinants. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:556–61.

Kataoka H. Biochemical determinants of changes in plasma volume after decongestion therapy for worsening heart failure. J Card Fail. 2019;25:213–7.

Kataoka H. Proposal for heart failure progression based on the “chloride theory”: worsening heart failure with increased vs. non-increased serum chloride concentration. ESC Heart Fail. 2017;4:623–31.

Kataoka H. The, “chloride theory”, a unifying hypothesis for renal handling and body fluid distribution in heart failure pathophysiology. Med Hypotheses. 2017;104:170–3.

Kataoka H. Treatment of hypochloremia with acetazolamide in an advanced heart failure patient and importance of monitoring urinary electrolytes. J Card Cases. 2018;17:80–4.

Liamis G, Liberopoulos E, Barkas F, Elisaf M. Diabetes mellitus and electrolyte disorders. World J Clin Cases. 2014;16:488–96.

Tahara A, Kurosaki E, Yokono M, Yamajuku D, Kihara R, Hayashizaki Y, Takasu T, Imamura M, Qun L, Tomiyama H, Kobayashi Y, Noda A, Sasamata M, Shibasaki M. Pharmacological profile of ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, in vitro and in vivo. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385:423–36.

Chen L, LaRocque L, Efe O, Wang J, Sands JM, Klein JD. Effect of dapagliflozin treatment on fluid and electrolyte balance in diabetic rats. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352:517–23.

Masuda T, Watanabe Y, Fukuda K, Watanabe M, Onishi A, Ohara K, Imai T, Koepsell H, Muto S, Vallon V, Nagata D. Unmasking a sustained negative effect of SGLT2 inhibition on body fluid volume in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;315:F653–64.

Johnsson K, Johnsson E, Mansfield TA, Yavin Y, Ptaszynska A, Parikh SJ. Osmotic diuresis with SGLT2 inhibition: analysis of events related to volume reduction in dapagliflozin clinical trials. Postgrad Med. 2016;128:346–55.

Higashikawa T, Ito T, Mizuno T, Ishigami K, Kohori M, Mae K, Sangen R, Usuda D, Saito A, Iguchi M, Kasamaki Y, Fukuda A, Saito H, Kanda T, Okuro M. The effects of 12-month administration of tofogliflozin on electrolytes and dehydration in many elderly Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:5117–26.

Bhave G, Neilson EG. Body fluid dynamics: back to the future. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2166–81.

Berend K, van Hulsteijn LH, Gans ROB. Chloride: the queen electrolytes? Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:203–11.

Kataoka H. The effusion-serum chloride gradient exists in heart failure associated pleural effusion. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(Supplement):176–7 (abstract).

Jiménez DL, Huelgas RG, González JP. The mechanism of action of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors is similar to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:409.

Kataoka H. Acetazolamide as a potent chloride-regaining diuretic: short- and long-term effects, and its pharmacologic role under the ‘chloride theory’ for heart failure pathophysiology. Heart Vessels. 2019;34:1952–60.

Costello-Boerrigter LC, Smith WB, Boerrigter G, Ouyang J, Zimmer CA, Orlandi C, Burnett JC Jr. Vasopressin-2-receptor antagonism augments water excretion without changes in renal hemodynamics or sodium and potassium excretion in human heart failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F273–8.

Kataoka H, Yamasaki Y. Strategy for monitoring decompensated heart failure treated by an oral vasopressin antagonist with special reference to the role of serum chloride: a case report. J Card Cases. 2016;14:185–8.

Kataoka H. Dynamic changes in serum chloride concentrations during worsening of heart failure and its recovery following conventional diuretic therapy. Health Sci Rep. 2018;1(11):e94.

Kataoka H. Comparison of changes in the plasma volume and renal function between acetazolamide vs. conventional diuretics: understanding their mechanical differences according to the chloride theory. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(Supplement):40–1 (abstract).

Hallow KM, Helmlinger G, Greasly PJ, McMurray JJ, Boulton DW. Why do SGLT2 inhibitors reduce heart failure hospitalization?: a differential volume regulation hypothesis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:479–87.

Ohara K, Masuda T, Murakami T, Imai T, Yoshizawa H, Nakagawa S, Okada M, Miki A, Myoga A, Sugase T, Sekiguchi C, Miyazawa Y, Maeshima A, Akimoto T, Saito O, Muto S, Nagata D. Effects of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on fluid distribution: a comparison study with furosemide and tolvaptan. Nephrology. 2019;24:904–11.

Kimura G. Importance of inhibiting sodium-glucose cotransporter and its compelling indication in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiological hypothesis. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:271–8.

Ansary TM, Nakano D, Nishiyama A. Diuretic effects of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and their influence on the renin-angiotensin system. Int J Med Sci. 2019;20:629.

Gilbert RE. Sodium-glucose linked transporter-2 inhibitors: potential for renoprotection beyond blood glucose lowering? Kidney Int. 2014;86:693–700.

Schork A, Saynisch J, Vosseler A, Jaghutriz BA, Heyne N, Peter A, Häring H-U, Stefan N, Fritsche A, Artunc F. Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on body composition, fluid status and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in type 2 diabetes: a prospective study using bioimpedance spectroscopy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:46.

Kataoka H. Rational of the “chloride theory” as an explanation for neurohormonal activity in heart failure pathophysiology: literature review. J Clin Exp Cardiol. 2019;10:634.

Lim HS, MacFadyen RJ, Lip GY. Diabetes mellitus, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and the heart. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1737–48.

Feldman M, Soni NJ, Dickson B. Use of sodium concentration and anion gap to improve correlation between serum chloride and bicarbonate concentrations. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:154–9.

Story DA, Morimatsu H, Bellomo R. Strong ions, weak acids and base excess: a simplified Fencl-Stewart approach to clinical acid-base disorders. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:54–60.

Forni LG, McKinnon W, Hilton PJ. Unmeasured anions in metabolic acidosis: unravelling the mystery. Crit Care. 2006;10:220.

Peters AL, Buschur EO, Buse JB, Cohan P, Diner JC, Hirsch IB. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a potential complication of treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1687–93.

Singh AK. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and euglycemic ketoacidosis: wisdom of hindsight. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:722–30.

Pessoa TD, Campos LC, Carraro-Lacroix L, Girardi AC, Malnic G. Functional role of glucose metabolism, osmotic stress, and sodium-glucose cotransporter isoform-mediated transport on Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 activity in the renal proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2018–39.

Layton AT, Vallon V, Edwards A. Modeling oxygen consumption in the proximal tubule: effects of NHE and SGLT2 inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308:F1343–57.

Gelbenegger G, Buchtele N, Schoergenhofer C, Roeggla M, Schwameis M. Severe hypernatraemia dehydration and unconsciousness in a care-dependent inpatient treated with empagliflozin. Drug Saf Case Rep. 2017;4:17.

Acknowledgements

The authors express appreciation to Mariko Wakita for her valuable assistance during the study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK was primarily responsible for planning the study, obtaining the approval of the ethics committee, supporting the performance of the study, evaluation of the data and writing the manuscript. YY decisively supported the performance of the study. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Nishida Hospital approved the study (No. 201611-01), and all patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kataoka, H., Yoshida, Y. Enhancement of the serum chloride concentration by administration of sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor and its mechanisms and clinical significance in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 12, 5 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-020-0515-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-020-0515-x