Abstract

Background

Estimation of pulmonary pressures is of key importance in acute cardiovascular and respiratory failure. Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAAT) has emerged as reliable parameter for the estimation of systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) in cardiological population with preserved right ventricular function. We sought to find whether PAAT correlates with sPAP in critically ill patients with and without right ventricular (RV) systolic dysfunction.

Methods

Observational study. We measured sPAP using continuous-wave Doppler analysis of tricuspid regurgitation velocity peak method and we assessed the validity of PAAT in estimating sPAP in patients admitted to adult intensive care unit (ICU) for acute cardiovascular and respiratory failure.

Results

We enrolled 236 patients admitted to cardiothoracic ICU for cardiovascular and respiratory failure (respectively: 129, 54.7% and 107, 45.3%). 114 (48.3%) had preserved RV systolic function (defined as TAPSE ≥ 17 mm), whilst 122 (51.7%) had RV systolic impairment (defined as TAPSE < 17 mm). A weak inverse correlation between PAAT and sPAP (ρ–0.189, p 0.0035) was observed in overall population, which was confirmed in those with preserved RV systolic PAAT and sPAP (ρ–0.361, p 0.0001). In patients with impaired RV systolic function no statistically significant correlation between PAAT and sPAP was demonstrated (p 0.2737). Adjusting PAAT values for log10, heart rate and RV ejection time did not modify the abovementioned correlations.

Conclusions

PAAT measurement to derive sPAP is not reliable in cardiothoracic critically ill patients, particularly in the coexistence of RV systolic impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a condition defined by an increase in afterload leading to a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mmHg at rest [1]. The presence of right ventricular (RV) dysfunction is associated with significant increase in mortality [1, 2]. Although, the diagnosis of PH requires right-heart catheterization, echocardiography is recommended as a first-line non-invasive diagnostic investigation for PH assessment (Class I, C) [1].

A number of echocardiographic parameters have been validated to assess RV morphology and function and to estimate pulmonary pressures [3]. Continuous-wave Doppler analysis of tricuspid regurgitation velocity peak (TRVmax) is considered the cornerstone of non-invasive assessment of systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) [1]. Although this method has shown a good correlation with invasive measurements, it is burdened with some limitations, including the dependency on a well-defined envelope of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and an adequate alignment with Doppler signal [4, 5].

Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAAT) has demonstrated good reliability in estimating mPAP [6, 7] and, recently, it has been considered an appealing alternative to TR-based method in the estimation of sPAP [8]. However, there is lack of data regarding the accuracy of this parameter in patients with RV dysfunction in acute setting.

We sought to investigate whether PAAT estimation of sPAP is reliable also in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) for acute cardiovascular failure and respiratory failure related to moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), with and without RV systolic dysfunction, defined as tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) < 17 mm [9].

Methods

The project has been approved by the ethical committee of Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK), where it was carried out. Written informed consent was acquired for all patients. The study was conducted on consecutive patients admitted to adult cardiothoracic ICU for post-cardiac surgery and respiratory failure related to at least moderate ARDS (PaO2 on FiO2 ratio below 200).

We measured sPAP using the TRVmax-method [1] and we assessed the validity of PAAT in estimating sPAP as previously described [8].

Exclusion criteria were: TR envelope judged as insufficient to assess the sPAP, pulmonary prothesis, tricuspid surgery, congenital heart disease and significant pulmonic valvular stenosis (as defined by a continuous-wave peak jet velocity ≥ 2 m/s across the pulmonic valve). Images were recorded in multiple views thus obtaining optimal imaging for the primary analysis.

TAPSE and tissue Doppler S’ was measured in the apical four-chamber view during systole with cursor placed through the lateral tricuspid annulus. In accordance with current guidelines, TAPSE < 17 mm and S’ < 9.5 cm/sec were regarded as pathological [10].

Continuous-wave Doppler was used to measure the peak velocity of the TRVmax. sPAP was determined from the TR jet velocity using the simplified Bernoulli equation adding the right atrial pressure (RAP), directly measured from central venous pressure (at end-expiration) or estimated from inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and respiratory collapsibility [11, 12].

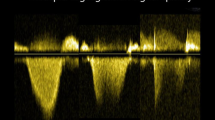

Doppler interrogation of the proximal pulmonary artery was performed either in parasternal long-axis outflow and/or the parasternal short-axis (Fig. 1A) in order to exclude pulmonic stenosis and to assess pulmonary artery flow; for patients with poor acoustic parasternal window short-axis subcostal view was preferred (Fig. 1B). Pulmonary artery flow was evaluated by placing the pulsed-wave Doppler sample volume at the pulmonary valve annulus: PAAT was calculated as the interval between the onset of ejection and the peak flow velocity. PAAT have also been indexed by RV ejection time (RVET) [13] and heart rate (HR), dividing its value for square root of RR interval [14, 15].

Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAAT, dashed red line) and right ventricular ejection time (RVET, yellow brace) measurement in parasternal short-axis view (A) and subcostal view (B). PAAT is calculated as the time interval between the onset of systolic pulmonary artery flow and its peak flow velocity; RVET is measured from the onset to the end of pulmonary artery Doppler spectrum. For further adjustment, sPAP was derived on the basis of the linear correlation linking PAAT to TRVmax as follows: log10(sPAP) = −0.004 (PAAT) + 2.1 [8]. Mean PAP (mPAP) can be estimated using the following formulae proposed by Dabestani et al. [28]: if PAAT ≥ 120 ms, mPAP = 79 – (0.45 * PAAT); if PAAT < 90 ms, mPAP = 90 – (0.62 * PAAT)

All values used for analysis represented the average of three consecutive cardiac cycles, with the exception of patients with atrial fibrillation, in whom five-beat averages were obtained. Continuous-wave Doppler was used with a sweep speed of 100 mm/s to achieve a satisfactory envelope.

All measurements were made offline. Echocardiograms were interpreted by fully certified physicians who were blinded to the patients’ medical history and diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Results of continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median (interquartile range) for values not normally distributed; normal distribution of data was assessed with D’Agostino–Pearson test. Categorical variables were expressed as percentage.

Categorical data were compared by Pearson’s χ2 test with Yates correction or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Continuous variables were compared with Mann–Whitney U-test for unpaired data. Relationships between PAAT and haemodynamic indexes were evaluated by Spearman correlation coefficient. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was assumed as statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software (version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The intra-observer and inter-observer variability of PAAT and TRVmax were expressed as intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), which was derived using a one‐way random‐effects model.

Results

Patients characteristics

We consecutively enrolled 255 adult patients admitted to cardiothoracic ICU. Nineteen subjects were excluded for inadequate echocardiographic windows, thus 236 patients were considered for the final analyses. The mean age was 63 ± 17 years, and 150 (63.5%) were males. 114 (48.3%) had preserved RV systolic function (defined as TAPSE ≥ 17 mm), whilst 122 (51.7%) had RV systolic impairment (defined as TAPSE < 17 mm). One hundred and twenty-nine patients (54.7%) were admitted after cardiac surgery, while 107 (45.3%) for respiratory failure related to moderate-to-severe ARDS. Amongst those undertaking cardiac surgery: 78 (60.5%) underwent mitral valve replacement, 32 (24.8%) aortic valve replacement and 19 (14.7%) coronary artery bypass graft. Two hundred and twenty patients had RAP derived from invasive measurements.

Stratifying for the cause of ICU admission, a statistically significant difference in the incidence of RV dysfunction was observed: 69.8% of patients affected by acute cardiovascular failure experienced RV dysfunction, while only 29.9% had RV dysfunction in the respiratory failure subgroup (p < 0.001). Need for positive-pressure ventilation (both invasive and non-invasive) and respiratory gas exchanges (PaO2 on FiO2 ratio and PaCO2) did not differ between the two cohorts. No patients required mechanical circulatory support nor inhaled nitric oxide at time of echocardiographic assessment.

Echocardiographic parameters tested and their derived variables, except for RAP and HR-corrected PAAT, shown a statistically significant difference between preserved and impaired RV function (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, patients admitted to ICU for acute cardio-circulatory failure were characterized by lower TAPSE and sPAP and shorter PAAT.

For the parameters measured, the operator intra‐observer correlation was, respectively, 0.98 (95% confidence interval of 0.978–0.989) and the inter‐observer variability was 0.94 (95% confidence interval of 0.92–0.95).

Correlation of PAAT with sPAP and TAPSE

Overall population

A weak inverse correlation between PAAT and sPAP (ρ 0.189, p 0.0035) was observed in overall population (Fig. 2 left upper panel). Adjusting PAAT for its logarithmic correction (log10PAAT) and HR did not increase the strength of this relation (respectively, ρ 0.190, p 0.0034; ρ 0.237, p 0.0002); PAAT adjusted for RVET did not correlate with sPAP (p 0.8110).

PAAT had also a weak-positive correlation with TAPSE (ρ 0.197, p 0.0024). Adjustment of PAAT for log10PAAT, HR and RVET did not yield significative increase in the strength of relationship with TAPSE (respectively, ρ 0.197, p 0.0023; p 0.6893; ρ 0.264, p < 0.0001).

The logistic regression adjusted for covariates including PEEP and reason for admission did not show any significant correlation.

Right ventricular systolic function

In patients with preserved RV systolic function, defined as TAPSE ≥ 17 mm and S’ ≥ 9.5 cm/sec, a weak inverse correlation between PAAT and sPAP was found (ρ 0.361, p 0.0001) (Fig. 2 right upper panel). This was confirmed either adjusting PAAT for log10 (ρ 0.364, p 0.0001) and HR (ρ 0.343, p 0.0002); no statistically significant correlation was found between PAAT adjusted for RVET and sPAP (p 0.1164). We did not find any statistically significant correlation between PAAT and TAPSE (p 0.2594), even after adjustment of PAAT for log10 (p 0.2876), HR (p 0.5873) and RVET (p 0.5565). The same applied for correlation between S’ and PAAT (p 0.134).

In the cohort of patients with impaired RV systolic function, no statistically significant correlation between PAAT and sPAP was demonstrated (p 0.2737) (Fig. 2 lower panel). Logarithmic, HR and RVET corrections of PAAT did not yield statistically significance to the relationship (respectively, p 0.2651, p 0.0521 and p 0.7691). Additionally, PAAT did not correlate with TAPSE (p 0.4515) neither with S’ (p > 0.5). Only adjustment of PAAT for HR yielded a weak inverse correlation with TAPSE (ρ 0.233, p 0.0135).

The strength of abovementioned correlations was not influenced by the addition of RAP to TRVmax pressure gradient (p > 0.5 for all).

Role of arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

In overall population, a weak-positive correlation between sPAP and PaCO2 was observed (ρ 0.268, p < 0.0001), PAAT had a weak-negative correlation with PaCO2 (ρ 0.226, p 0.0005), and a weak-positive correlation between TAPSE and PaCO2 was found (ρ 0.146, p 0.0258).

Table 3 shows the correlations, and relative strength, between echocardiographic parameters and PaCO2 in patients with preserved and impaired RV systolic function.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that PAAT is not a reliable parameter to estimate sPAP in patients admitted to cardiothoracic ICU with and without RV systolic dysfunction.

According to the current guidelines, TVRmax is considered the non-invasive parameter of choice for establishing the suspicion of PH. However, TR-methods of estimation of pulmonary artery pressure are burdened with some limitations: (1) difficult measurement of TVRmax in trivial or mild TR; (2) sub-optimal Doppler signal alignment with TR jet; (3) underestimation of RA–RV gradient in severe TR, due to the early equalization of chamber pressures [9]; (4) the interrelation between TR peak velocity and RV systolic function; and (5) the inter-observer variability in TR jet quantification [4].

Given the non-negligible pitfalls of TR-derived methods, alternative TR-independent methods, have been proposed for the evaluation of pulmonary artery pressure. It has previously been shown that PAAT should be possible to measure in 99% of patients out of which 25% has no measurable TR and thus provide a way of estimating the pulmonary pressure non-invasively [8]. Different studies, including a recent meta-analysis have demonstrated a reasonable accuracy of PAAT in correctly estimating sPAP and mPAP [3, 16,17,18].

The evaluation and treatment of RV dysfunction is particularly challenging in critically ill and the coexistence of RV failure and PH is burdened by an increased mortality [19, 20]. While a recent study has assessed the diagnostic accuracy of echocardiography in ventilated patients, no studies were reported of PAAT in patients admitted in ICU with RV dysfunction [21].

Normal PAAT interval values in adults range from 136 to 153 ms [22]. PAAT may be shortened in PH because of a number of reasons: enhanced early pulmonary ejection, increased pulmonary vascular resistance and loss of lung compliance leading to a rapid increase and reduction of flow velocity [15, 23]. PAAT, in fact, represents pulmonary flow acceleration, which increases as the vascular resistance is augmented, based on the Newton law of motion.

Our results are partially in contradiction with the previous literature, as also patients without RV dysfunction did not prove strong relation between Doppler-derived PAAT and TR-estimated sPAP. One of the potentially explaining difference is the admission underlying pathology. Respiratory pathologies may highly influence the interaction between RV and pulmonary circulation system both in settings of normal and impaired RV systolic function [24]. An elegant study on cyclic changes in RV impedance during mechanical ventilation had shown the strict dependence of RV cardiac output and pulmonary artery flow velocity on the ventricular afterload. Noteworthy, the PAAT of those patients were close to normal values during positive-pressure ventilation (104 ms) [25], while our population exhibited lower values.

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) has a well-defined role in determining pulmonary vascular resistances [26, 27], having vasoconstrictive effect on pulmonary circulation. In our study population, we found a positive correlation between TR-derived sPAP and values of PaCO2. However, no correlation between PAAT and PaCO2 was found in patients with impaired RV systolic function suggesting further caution in the use of PAAT to estimate pulmonary artery pressure.

Limitations

The present study has a number of limitations: (1) the limited sample size; (2) the heterogeneous population; and (3) sPAP has been assessed only with echocardiography and no validation with pulmonary artery catheter was performed (because of the nature of the observational study and pulmonary artery catheter is not part of the clinical routine armamentarium).

Although echocardiography presents well-known limitations, which are listed in the manuscript, it is considered a reliable diagnostic tool in PH. Additionally, the same methodology has been used in other studies already published and included in the referenced meta-analyses [8, 16].

Conclusions

sPAP evaluation may be extremely useful in patients with acute respiratory failure, although its estimation based on TR jet may be unfeasible. PAAT measurement to derive sPAP is not reliable in cardiothoracic critically ill patients, particularly in the coexistence of RV systolic impairment. Non-invasive echocardiographic estimation of pulmonary artery pressure in suspected and proven PH remains a challenge, especially in ICU patients. In this specific clinical setting, echocardiographic parameters validated in outpatient population should be adopted with caution.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Disease Classification System II

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- FiO2 :

-

Inspired oxygen fraction

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- mPAP:

-

Mean pulmonary artery pressure

- PAAT:

-

Pulmonary artery acceleration time

- PaCO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PaO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PH:

-

Pulmonary hypertension

- RAP:

-

Right atrial pressure

- RR:

-

ECG RR interval

- RV:

-

Right ventricle

- RVET:

-

Right ventricular ejection time

- sPAP:

-

Systolic pulmonary artery pressure

- TAPSE:

-

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- TR:

-

Tricuspid regurgitation

- TRVmax :

-

Tricuspid regurgitation velocity peak

References

Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M, Group ESCSD (2016) 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the joint task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 37(1):67–119

Sztrymf B, Souza R, Bertoletti L, Jais X, Sitbon O, Price LC, Simonneau G, Humbert M (2010) Prognostic factors of acute heart failure in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 35(6):1286–1293

Hellenkamp K, Unsöld B, Mushemi-Blake S, Shah AM, Friede T, Hasenfuß G, Seidler T (2018) Echocardiographic estimation of mean pulmonary artery pressure: a comparison of different approaches to assign the likelihood of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31(1):89–98

Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E, Housten-Harris T, Champion HC, Girgis RE, Corretti MC, Hassoun PM (2009) Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179(7):615–621

Amsallem M, Sternbach JM, Adigopula S, Kobayashi Y, Vu TA, Zamanian R, Liang D, Dhillon G, Schnittger I, McConnell MV, Haddad F (2016) Addressing the controversy of estimating pulmonary arterial pressure by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29(2):93–102

Yock PG, Popp RL (1984) Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation 70(4):657–662

Lindqvist P, Soderberg S, Gonzalez MC, Tossavainen E, Henein MY (2011) Echocardiography based estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a simultaneous Doppler echocardiography and cardiac catheterization study. Eur J Echocardiogr 12(12):961–966

Yared K, Noseworthy P, Weyman AE, McCabe E, Picard MH, Baggish AL (2011) Pulmonary artery acceleration time provides an accurate estimate of systolic pulmonary arterial pressure during transthoracic echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 24(6):687–692

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt J-U (2015) Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16(3):233–271

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU (2015) Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 28(1):1-39 e14

Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB (2010) Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23(7):685–713

Beigel R, Cercek B, Luo H, Siegel RJ (2013) Noninvasive evaluation of right atrial pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26(9):1033–1042

Masuyama T, Kodama K, Kitabatake A, Sato H, Nanto S, Inoue M (1986) Continuous-wave Doppler echocardiographic detection of pulmonary regurgitation and its application to noninvasive estimation of pulmonary artery pressure. Circulation 74(3):484–492

Urboniene D, Haber I, Fang YH, Thenappan T, Archer SL (2010) Validation of high-resolution echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging vs. high-fidelity catheterization in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299(3):L401–L412

Mallery JA, Gardin JM, King SW, Ey S, Henry WL (1991) Effects of heart rate and pulmonary artery pressure on Doppler pulmonary artery acceleration time in experimental acute pulmonary hypertension. Chest 100(2):470–473

Wang YC, Huang CH, Tu YK (2018) Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary artery acceleration time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31(2):201-210 e3

Kitabatake A, Inoue M, Asao M, Masuyama T, Tanouchi J, Morita T, Mishima M, Uematsu M, Shimazu T, Hori M, Abe H (1983) Noninvasive evaluation of pulmonary hypertension by a pulsed Doppler technique. Circulation 68(2):302–309

Wierzbowska-Drabik K, Picano E, Bossone E, Ciampi Q, Lipiec P, Kasprzak JD (2019) The feasibility and clinical implication of tricuspid regurgitant velocity and pulmonary flow acceleration time evaluation for pulmonary pressure assessment during exercise stress echocardiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 20(9):1027–1034

Hoeper MM, Granton J (2011) Intensive care unit management of patients with severe pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184(10):1114–1124

Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Celutkiene J, Bettex D, Bueno H, Chioncel O, Crespo-Leiro MG, Falk V, Filippatos G, Gibbs S, Leite-Moreira A, Lassus J, Masip J, Mueller C, Mullens W, Naeije R, Nordegraaf AV, Parissis J, Riley JP, Ristic A, Rosano G, Rudiger A, Ruschitzka F, Seferovic P, Sztrymf B, Vieillard-Baron A, Yilmaz MB, Konstantinides S (2016) Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 18(3):226–241

Mercado P, Maizel J, Beyls C, Kontar L, Orde S, Huang S, McLean A, Tribouilloy C, Slama M (2019) Reassessment of the accuracy of cardiac Doppler pulmonary artery pressure measurements in ventilated ICU patients. Crit Care Med 47(1):41–48

Tossavainen E, Soderberg S, Gronlund C, Gonzalez M, Henein MY, Lindqvist P (2013) Pulmonary artery acceleration time in identifying pulmonary hypertension patients with raised pulmonary vascular resistance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 14(9):890–897

Koestenberger M, Grangl G, Avian A, Gamillscheg A, Grillitsch M, Cvirn G, Burmas A, Hansmann G (2017) Normal reference values and z scores of the pulmonary artery acceleration time in children and its importance for the assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005336

Pinsky MR (2016) The right ventricle: interaction with the pulmonary circulation. Crit Care 20:266

Vieillard-Baron A, Loubieres Y, Schmitt JM, Page B, Dubourg O, Jardin F (1999) Cyclic changes in right ventricular output impedance during mechanical ventilation. J Appl Physiol 87(5):1644–1650

Mekontso Dessap A, Charron C, Devaquet J, Aboab J, Jardin F, Brochard L, Vieillard-Baron A (2009) Impact of acute hypercapnia and augmented positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricle function in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 35(11):1850–1858

Balanos GM, Talbot NP, Dorrington KL, Robbins PA (2003) Human pulmonary vascular response to 4 h of hypercapnia and hypocapnia measured using Doppler echocardiography. J Appl Physiol 94(4):1543–1551

Dabestani A, Mahan G, Gardin JM, Takenaka K, Burn C, Allfie A, Henry WL (1987) Evaluation of pulmonary artery pressure and resistance by pulsed Doppler echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 59(6):662–668

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have equally contributed to the drafting of this manuscript and to the analysis of its content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study has been approved by the ethical committee of Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

FM received fees for lectures from GE Healthcare, Hamilton Medical, SEDA SpA, outside the present work. GT received fees for lectures from GE Healthcare, outside the present work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dammassa, V., Corradi, F., Colombo, C.N.J. et al. Pulmonary artery acceleration time accuracy for systolic pulmonary artery pressure estimation in critically ill patients. Ultrasound J 14, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-022-00276-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-022-00276-4