Abstract

Background

Sarcopenic obesity, associated with greater risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), may be related to dysregulated muscle remodeling. To determine whether exercise training could improve remodeling, we measured changes in inter-relationships of plasma galectin-3, skeletal muscle cytokines, and muscle myostatin in patients with RA and prediabetes before and after a high-intensity interval training (HIIT) program.

Methods

Previously sedentary persons with either RA (n = 12) or prediabetes (n = 9) completed a 10-week supervised HIIT program. At baseline and after training, participants underwent body composition (Bod Pod®) and cardiopulmonary exercise testing, plasma collection, and vastus lateralis biopsies. Plasma galectin-3, muscle cytokines, muscle interleukin-1 beta (mIL-1β), mIL-6, mIL-8, muscle tumor necrosis factor-alpha (mTNF-α), mIL-10, and muscle myostatin were measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. An independent cohort of patients with RA (n = 47) and age-, gender-, and body mass index (BMI)-matched non-RA controls (n = 23) were used for additional analyses of galectin-3 inter-relationships.

Results

Exercise training did not reduce mean concentration of galectin-3, muscle cytokines, or muscle myostatin in persons with either RA or prediabetes. However, training-induced alterations varied among individuals and were associated with cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition changes. Improved cardiorespiratory fitness (increased absolute peak maximal oxygen consumption, or VO2) correlated with reductions in galectin-3 (r = −0.57, P = 0.05 in RA; r = −0.48, P = 0.23 in prediabetes). Training-induced improvements in body composition were related to reductions in muscle IL-6 and TNF-α (r < −0.60 and P <0.05 for all). However, the association between increased lean mass and decreased muscle IL-6 association was stronger in prediabetes compared with RA (Fisher r-to-z P = 0.0004); in prediabetes but not RA, lean mass increases occurred in conjunction with reductions in muscle myostatin (r = −0.92; P <0.05; Fisher r-to-z P = 0.026). Subjects who received TNF inhibitors (n = 4) or hydroxychloroquine (n = 4) did not improve body composition with exercise training.

Conclusion

Exercise responses in muscle myostatin, cytokines, and body composition were significantly greater in prediabetes than in RA, consistent with impaired muscle remodeling in RA. To maximize physiologic improvements with exercise training in RA, a better understanding is needed of skeletal muscle and physiologic responses to exercise training and their modulation by RA disease–specific features or pharmacologic agents or both.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02528344. Registered on August 19, 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite improvements in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease management with biologic therapies, patients with RA remain at greater risk than the general population for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and reduced life expectancy [1,2,3]. RA-associated CVD, disability, and increased mortality are linked to adverse changes in body composition, including decreased skeletal muscle mass and increased fat mass—referred to as sarcopenic obesity [4, 5]. We previously reported that RA sketelal muscle is defined by increased interleukin-6 (IL-6), increased inflammation, increased glycolysis, and a dysregulated remodeling transcriptomic and metabolic signature [6]; these findings overall suggests that RA muscle is deficient in adaptation to physical activity and repair of injuries.

In response to injury, skeletal muscle normally relies on a coordinated activation and deactivation of the inflammatory response to produce myofiber hypertrophy and vascular maturation without excess production of collagen or fibrosis [7]. This process requires immune cells, muscle stem (satellite) cells, and fibroblasts. These cells communicate via well-coordinated systemic and local signaling molecules, including cytokines and myokines [8]. IL-6 and myostatin are critical for muscle hypertrophy and remodeling [9]; myostatin is a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily and a potent negative regulator of muscle hypertrophy [10].

Galectin-3, a beta-galactoside–binding lectin important for muscle repair [11], is implicated in synovial inflammation and acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator of disease activity in RA [12, 13]. A regulatory molecule of chronic inflammation, galectin-3 mediates transitions from acute to chronic inflammation to fibrosis and organ scarring [14, 15]. Galectin-3 may serve as a marker of impaired muscle remodeling; in RA, although responses to chronic exercise training are unknown, serum galectin-3 is unchanged after an acute bout of exercise [16].

The pro-inflammatory, pro-glycolytic, dysregulated muscle phenotype of RA is associated with less physical activity, suggesting that exercise training may counteract the impaired muscle remodeling associated with RA [6]. We hypothesized that (1) a high-intensity interval-based training program would improve skeletal muscle remodeling reflected by reductions in remodeling markers: muscle inflammatory cytokines, myostatin, and plasma galectin-3; (2) changes in remodeling markers would be associated with improvements in clinical measures of body composition (goal to increase lean mass and decrease body fat) and cardiopulmonary fitness; and (3) remodeling markers and clinical associations in subjects with RA would differ from those in subjects with prediabetes. A convenience sample of subjects with prediabetes was chosen as a comparator cohort with a CVD risk similar to that of RA.

Methods

Study design and participants

Previously sedentary volunteers with RA underwent a high-intensity interval walking program. Subjects with RA met the following criteria: (1) RA diagnosis meeting American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 criteria who were either seropositive or with hand radiographic joint erosions [17], (2) no medication changes in the previous 3 months; (3) using doses of prednisone of 5 mg per day or less; and (4) exercising less than 2 days per week at baseline.

To better determine RA-specific changes, this report includes a cohort of persons with prediabetes who underwent an identical exercise training and assessment protocol. Subjects with prediabetes met the following criteria: (1) hemoglobin A1c 5.7–6.5%, (2) stable use of all medications for at least 3 months, and (3) exercising less than 2 days per week at baseline. For both groups, exclusions were diagnoses of diabetes mellitus or CVD and an inability to walk unaided on a treadmill. A previously described cross-sectional cohort of subjects with RA [6] was used to compare plasma galectin-3 between RA and age-, gender-, and body mass index (BMI)-matched controls. This cohort was seropositive or with erosive hand disease, met 1987 ACR criteria for RA, had no medication changes in the last 3 months, and was using prednisone 5 mg a day or less; persons with diabetes or CVD diagnoses were excluded. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved all research protocols, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Exercise intervention

Supervised exercise sessions occurred three times per week for 10 weeks using graded treadmills and continuous heart rate monitoring (HRM1G Heart Rate Monitor with the compatible FR60 watch; Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA). Each session consisted of a 5-min warm-up, 10 alternating high-intensity (80–90% heart rate reserve) and low-intensity (50–60% heart rate reserve) intervals (60–90 s each), and a 5-min cool-down.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were changes in immune cell function and plasma cytokines, which have been previously reported [18]. Medical history questionnaire and additional assessments—body composition, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2), and disease activity—were conducted at baseline and between 24 and 48 h after the last exercise-training bout (Table 1). Body composition was assessed via air displacement plethysmography by using a BodPod® (BodPod System; Life Measurement Corporation, Concord, CA, USA). Maximal oxygen consumption during exercise, or peak VO2, was directly assessed via graded exercise treadmill testing. Disease activity was assessed by the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS-28) as determined from a patient-completed visual analog scale, physician-determined numbers of tender and swollen joints, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [19].

Participants underwent fasting phlebotomy and Bergstrom needle vastus lateralis biopsies [20]. Plasma and flash-frozen muscle tissue were stored at −80 °C until analyses. Plasma concentrations of inflammatory markers, cytokines, and galectin-3 (R&D cat. no. DGAL30) were determined by immunoassay [6, 21]. Skeletal muscle was homogenized and sample concentrations were normalized to initial masses as previously described [6]. Muscle interleukin 1 beta (mIL-1β), mIL-6, mIL-8, muscle tumor necrosis factor-alpha (mTNF-α) (MSD 4-plex; K15053D-1), mIL-10 (MSD K151QUD-1), and myostatin (R&D cat. no. DGDF80) were measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Mean concentrations were above the lower limit of detection for each analyte. For all six analytes, mean intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 6.5% and 12%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

As determined by the distribution of the variable, continuous outcome variables were compared by using either Student’s t tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Spearman correlations were used to determine the relationships between the plasma and muscle measures. Strengths of associations for the two groups (RA and prediabetes) were compared with Fisher r-to-z transformations [22]. Except for Fisher transformations, all statistical analyses were performed by using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Remodeling markers in RA at baseline

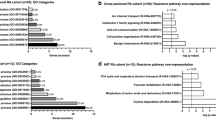

In a previously described RA cohort [6], plasma galectin-3 was significantly (n = 47, P <0.05 for all) and positively correlated with plasma IL-6 (r = 0.29), prednisone use (r = 0.42), BMI (r = 0.32), thigh cross-sectional area (r = 0.46), intra-muscular fat (thigh muscle density, r = −0.44), and age (r = 0.39). Plasma galectin-3 was greater in older (age greater than 55) persons with RA (n = 24; 8.80 ± 3.5 (standard deviation) ng/mL) than age-, gender-, and BMI-matched healthy controls (n = 12; 6.89 ± 1.9 ng/mL; P = 0.042; Fig. 1).

Plasma galectin-3 in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared with healthy controls. Graphs comparing plasma galectin-3 in older RA subjects (n = 24; age >55) with older age-, sex-, and body mass index (BMI)-matched controls (n = 12; age >55). *P <0.05 for comparisons between older RA group (age greater than 55) and older controls (age greater than 55)

Prior to exercise training, those with RA, compared with those with prediabetes, had similar muscle cytokine concentrations but greater plasma galectin-3 and less skeletal muscle myostatin (P <0.05 for myostatin; Table 2). In RA, muscle cytokines were not significantly associated with previously reported plasma cytokines [18].

Changes in remodeling markers with exercise training

For both groups, training produced robust improvements in peak VO2 and DAS-28 (Table 1) [18]. However, plasma galectin-3, skeletal muscle cytokines, and muscle myostatin concentrations did not respond to training in either group (Table 2).

Associations of remodeling markers with cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in RA

Responses of remodeling markers (muscle inflammatory cytokines, myostatin, and plasma galectin-3) varied among individuals and were associated with cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition responses in RA. Improved cardiorespiratory fitness (peak VO2) correlated with reductions in galectin-3 (Fig. 2). Training-induced improvements in body composition (increased lean mass) were related to reductions in skeletal muscle IL-6 and TNF-α (r < −0.60 and P <0.05 for all; Fig. 3). Changes in lean mass and body fat were not associated with changes in plasma galectin-3.

Plasma galectin-3 correlations before and after high-intensity interval training (HIIT). a Scatter plot depicting relationships between change in plasma galectin-3 (y-axis) and change in absolute peak VO2 (x-axis) following exercise training in the rheumatoid arthritis group (n = 12; r = −0.57; P = 0.05). b Scatter plot depicting the Spearman’s correlation coefficient for change in plasma galectin-3 (y-axis) and change in absolute peak VO2 (x-axis) following exercise training in the prediabetes group (n = 9; r = −0.48, P = 0.23), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.81. Abbreviation: VO2 maximal oxygen consumption

Body composition correlations in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and prediabetes. Scatter plot depicting the relationships between (a) change in lean mass (y-axis) and change in muscle myostatin (x-axis) following exercise training in RA (r = −0.39, P = 0.23); (b) change in lean mass and change in muscle myostatin in prediabetes (PD) (r = −0.92, P = 0.0005), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.026; (c) change in lean mass and change in muscle interleukin-6 (IL-6) in RA (r = −0.65; P = 0.023); (d) change in lean mass and change in muscle IL-6 in prediabetes (r = −0.98, P <0.0001), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.0004; (e) change in lean mass and change in muscle IL-1β in RA (r = −0.63; P = 0.049); (f) change in lean mass and change in muscle IL-1β in prediabetes (r = −0.38, P = 0.31), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.516; (g) change in lean mass and change in muscle tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in RA (r = −0.68; P = 0.023); (h) change in lean mass and change in muscle TNF-α in prediabetes (r = −0.82, P = 0.002), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.516; (i) change in body fat percentage and change in muscle TNF-α in RA (r = 0.67; P = 0.022); and (j) change in body fat percentage and change in muscle TNF-α in prediabetes (r = −0.07, P = 0.88), Fisher r-to-z P = 0.095

Associations of remodeling markers with cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in prediabetes

The inverse relationship of improved cardiorespiratory fitness (peak VO2) with reductions in galectin-3 was similar to RA, but non-significant, in prediabetes (Fisher r-to-z P = 0.81; Fig. 2). In prediabetes but not RA, body composition improvements correlated with reductions in muscle myostatin (r = −0.92; P <0.05; Fisher r-to-z P = 0.026; Fig. 3). The association of increased lean mass with decreased muscle IL-6 was significantly stronger in prediabetes (Fisher r-to-z P = 0.0004; Fig. 3).

Associations of RA medication use with body composition

All RA participants who achieved the goal combination of increased lean mass and decreased percentage body fat after exercise training (n = 4) were taking methotrexate (n = 3), sulfasalazine (n = 1), or tofacitinib (n = 1). In contrast, no person on TNF inhibitor (n = 4) or hydroxychloroquine therapy (n = 4) achieved the goal combination of increased lean mass and decreased fat mass after exercise training (r = −0.50, P = 0.098 for both; Table 3).

Discussion

As a systemic marker and regulator of chronic inflammation leading to tissue fibrogenesis, galectin-3 may reflect increased cardiovascular risk in RA resulting from impaired muscle remodeling. Elevated serum levels of galectin-3 are strongly associated with increased morbidity and mortality from CVD and heart failure [23, 24]. In the larger, cross-sectional cohort of RA subjects, the strongest associations for galectin-3 were with age and measures of sarcopenic obesity (increased adiposity and reduced muscle mass). In the exercise-training cohort, prediabetes was chosen as a comparator group for having a baseline CVD risk similar to that of RA. Although those with RA were younger than those with prediabetes, RA had greater plasma galectin-3. This finding is aligned with a previous study showing greater levels of galectin-3 in RA sera and synovial fluid [12]. Thus, galectin-3 may reflect non-traditional CVD risk factors, including sarcopenic obesity, which are present in younger persons with RA [16, 23, 24]. Most important, training-mediated reductions in galectin-3 were associated with improved cardiopulmonary fitness and cardiovascular function, indicative of reduced risk of mortality [25]. These findings suggest that galectin-3 may represent a novel risk factor for CVD and a marker of abnormal muscle remodeling in RA that can be modulated by exercise training.

In contrast to our hypothesis, plasma galectin-3, skeletal muscle cytokines, and muscle myostatin were unaffected by 10 weeks of high-intensity interval training in persons with RA and prediabetes. This is a surprising finding given that RA disease activity, as measured by DAS-28, significantly improved with exercise training, as previously discussed by our group [18]. One explanation for why plasma galectin-3 did not associate with disease activity is that it may more closely represent the chronic inflammatory state leading to CVD and mortality risk in RA as opposed to the acute inflammatory state that likely drives disease activity scores. We hypothesize that a longer duration of exercise training with more robust improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness would likely lead to significant reductions in systemic galectin-3 given the associations discussed above. The mechanisms driving exercise-training effects on acute and chronic systemic and tissue-specific inflammation certainly warrant further investigation.

However, despite insignificant group-level changes, reductions in muscle cytokines mIL-6, mIL-1β, and mTNF-α were associated with the goal body composition changes of increased lean mass and decreased body fat. Perhaps most interestingly, the association of reduced muscle IL-6 with improved body composition was greater in prediabetes than RA. Moreover, in prediabetes but not in RA, myostatin was reduced in association with increased muscle mass. These cohort differences signify that skeletal muscle remodeling is impaired in RA even when compared with a group with similar CVD risk; in part, RA disease–specific features or pharmacologic agents (or both) may underlie the impaired adaptations to exercise training.

RA therapeutic agents may prevent or permit improved exercise-mediated muscle remodeling. Intriguingly, of the four patients with improved measures of sarcopenic obesity (combination of a decrease in body fat and an increase in lean body mass) after exercise training, none was concomitantly using TNF inhibitors or hydroxychloroquine. In addition, all four patients on TNF inhibitors had an increase in BMI and body fat at the end of the study. Our findings are supported by others, where tight control of RA disease activity with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic agents (DMARDs) without biologics or exercise training had no overall effect on body composition [26]. Interestingly, as compared with those who received traditional DMARDs (“triple therapy” with methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine), patients with early RA treated with a TNF inhibitor, infliximab, increased body fat [27]. A randomized trial comparing patients with early RA treated with etanercept compared with methotrexate found no difference in body composition in either group at 24 weeks, but there was a trend toward gaining fat-free mass by those on etanercept [28]. In contrast, patients with RA treated for 24 weeks with tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptor, had no fat mass changes but increased lean mass [29]. Taken together, these results suggest that IL-6 inhibition, as opposed to TNF inhibition, may contribute to beneficial body composition changes in RA.

Obesity, sedentary behavior, and chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA are all associated with a chronic elevation in serum IL-6 [6, 30]. In response to acute exercise and in a TNF-α–independent fashion, skeletal muscle releases IL-6, leading to short-term beneficial metabolic and immunoregulatory effects [31]. With chronic exercise training, basal serum IL-6 is reduced [31]. Although we observed no overall change in skeletal muscle or serum IL-6 with exercise training, reductions in muscle IL-6 were tied to increased muscle mass more closely in subjects with prediabetes compared with RA. One possible explanation is that, in RA, persistently heightened systemic IL-6 contributes to sarcopenic obesity by impairing the normal muscle adaptive responses to exercise training. Specifically, chronic over-expression of systemic IL-6 dampens the skeletal muscle’s secretion of, or response to, IL-6 with an acute exercise bout; furthermore, a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation and physical inactivity drives skeletal muscle “IL-6 resistance”—negating of the beneficial effects of IL-6—when released from skeletal muscle as a myokine [9, 32]. Whether IL-6 inhibition is the answer to counteract these maladaptive changes, improve body composition, and in turn decrease risk of CVD in RA merits further study.

In addition to IL-6, impaired myostatin and muscle cytokine signaling may contribute to RA-associated sarcopenic obesity. One would expect lower myostatin, as a potent negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth and hypertrophy, to correspond to greater lean mass [10]. However, despite less myostatin in RA, muscle mass was not greater than an older, prediabetic group. Also, while exercise training did not reduce either group’s myostatin concentrations, myostatin responses were related to lean mass changes in prediabetes but not in RA. Thus, reducing myostatin appears insufficient for producing muscle hypertrophy in RA. Similarly, in RA, associations between responses in muscle cytokines and body composition were less pronounced than in prediabetes. Thus, although exercise training may improve coordination of cytokines and myokines critical for skeletal muscle remodeling, in RA, muscle adaptations to exercise training appear disrupted, possibly by external influences such as medication use or systemic immune dysregulation.

As is the nature of a pilot study, this investigation has multiple limitations. With a larger sample size or a longer duration of exercise training, we may have detected significant within- and between-group training-induced changes in skeletal muscle remodeling markers. Additionally, individuals with RA received multiple pharmacologic regimens, complicating analyses to determine effects of individual medications or combinations on muscle remodeling. Despite this, fascinatingly, no patient using a TNF inhibitor or hydroxychloroquine achieved the goal body composition change of a net decrease in body fat and increase in lean mass. Although we did not identify the cellular source of muscle cytokines and myostatin, it is notable that serum cytokines were found to have minimal association with cytokines measured in muscle tissue.

Conclusions

After a 10-week high-intensity interval training program in both RA and prediabetes cohorts, changes in intramuscular cytokine profiles were associated with the goal body composition changes of increased lean muscle mass and decreased body fat percentage. Decreased serum galectin-3 was also associated with decreased intramuscular fat in the cross-sectional RA cohort and with improved cardiorespiratory fitness after exercise training. These findings suggest that exercise-mediated body composition and cardiovascular risk improvements are closely tied to—and likely depend upon—effective muscle remodeling. However, the correlations of muscle remodeling markers (myostatin and cytokines) with favorable body composition outcomes were stronger in prediabetes than in RA. These differences provide further evidence to support the occurrence of abnormal muscle remodeling in RA and offer insights into the etiology of exercise intolerance and disability in RA. Further work should focus on better understanding the complex interplay between disease-modifying pharmacotherapy, exercise, cardiorespiratory fitness, and body composition to better improve disability and decrease the risk of CVD and mortality in RA.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DAS-28:

-

Disease Activity Score in 28 joints

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic agent

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- VO2 :

-

Maximal oxygen consumption

References

Svensson AL, Christensen R, Persson F, Løgstrup BB, Giraldi A, Graugaard C, et al. Multifactorial intervention to prevent cardiovascular disease in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009134.

Holmqvist ME, Wedren S, Jacobsson LT, Klareskog L, Nyberg F, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, et al. Rapid increase in myocardial infarction risk following diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis amongst patients diagnosed between 1995 and 2006. J Intern Med. 2010;268:578–85.

Lindhardsen JO, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Madsen OR, Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:929–34.

Biolo G, Cederholm T, Muscaritoli M. Muscle contractile and metabolic dysfunction is a common feature of sarcopenia of aging and chronic diseases: from sarcopenic obesity to cachexia. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:737–48.

Giles JT, Ling SM, Ferrucci L, Bartlett SJ, Andersen RE, Towns M, et al. Abnormal body composition phenotypes in older rheumatoid arthritis patients: association with disease characteristics and pharmacotherapies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:807–15.

Huffman KM, Jessee R, Andonian B, Davis BN, Narowski R, Huebner JL, et al. Molecular alterations in skeletal muscle in rheumatoid arthritis are related to disease activity, physical inactivity, and disability. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:12.

Novak ML, Koh TJ. Phenotypic transitions of macrophages orchestrate tissue repair. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1352–63.

Lightfoot AP, Cooper RG. The role of myokines in muscle health and disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:661–6.

Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:457–65.

Rodriguez J, Vernus B, Chelh I, Cassar-Malek I, Gabillard JC, Hadj Sassi A, et al. Myostatin and the skeletal muscle atrophy and hypertrophy signaling pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:4361–71.

Rancourt A, Dufresne S, St-Pierre G, Lévesque J, Nakamura H, Kikuchi Y, et al. Galectin-3 and N-acetylglucosamine promote myogenesis and improve skeletal muscle function in the mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 2018:fj201701151RRR.

Ohshima S, Kuchen S, Seemayer CA, Kyburz D, Hirt A, Klinzing S, et al. Galectin 3 and its binding protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2788–95.

Forsman H, Islander U, Andréasson E, Andersson A, Onnheim K, Karlström A, et al. Galectin 3 aggravates joint inflammation and destruction in antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:445–54.

Henderson NC, Sethi T. The regulation of inflammation by galectin-3. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:160–71.

Henderson NC, Mackinnon AC, Farnworth SL, Kipari T, Haslett C, Iredale JP, et al. Galectin-3 expression and secretion links macrophages to the promotion of renal fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:288–98.

Issa SF, Christensen AF, Lottenburger T, Junker K, Lindegaard H, Hørslev-Petersen K, et al. Within-day variation and influence of physical exercise on circulating Galectin-3 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and healthy individuals. Scand J Immunol. 2015;82:70–5.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24.

Bartlett DB, Willis LH, Slentz CA, Hoselton A, Kelly L, Heubner JL, et al. Ten weeks of high-intensity interval walk training is associated with reduced disease activity and improved innate immune function in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:127.

Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty eight- joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8.

Bergstrom J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1975;35:609–16.

AbouAssi H, Tune KN, Gilmore B, Bateman LA, McDaniel G, Muehlbauer M, et al. Adipose depots, not disease-related factors, account for skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in established and treated rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1974–9.

VassarStats: website for statistical computation. Vassar College. 1998–2015. http://vassarstats.net. Accessed May 2017.

van der Velde AR, Gullestad L, Ueland T, Aukrust P, Guo Y, Adourian A, et al. Prognostic value of changes in galectin-3 levels over time in patients with heart failure: data from CORONA and COACH. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:219–26.

Imran TF, Shin HJ, Mathenge N, Wang F, Kim B, Joseph J, et al. Meta-Analysis of the Usefulness of Plasma Galectin-3 to Predict the Risk of Mortality in Patients With Heart Failure and in the General Population. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:57–64.

Harber MP, Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Myers J, et al. Impact of Cardiorespiratory Fitness on All-Cause and Disease-Specific Mortality: Advances Since 2009. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:11–20.

Lemmey AB, Wilkinson TJ, Clayton RJ, Sheikh F, Whale J, Jones HS, et al. Tight control of disease activity fails to improve body composition or physical function in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1736–45.

Engvall IL, Tengstrand B, Brismar K, Hafström I. Infliximab therapy increases body fat mass in early rheumatoid arthritis independently of changes in disease activity and levels of leptin and adiponectin: a randomised study over 21 months. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R197.

Marcora SM, Chester KR, Mittal G, Lemmey AB, Maddison PJ. Randomized phase 2 trial of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for cachexia in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1463–72.

Tournadre A, Pereira B, Dutheil F, Giraud C, Courteix D, Sapin V, et al. Changes in body composition and metabolic profile during interleukin 6 inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:639–46.

Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, Blondy P, Capeau J, Laville M, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3338–42.

Fischer CP. Interleukin-6 in acute exercise and training: what is the biological relevance? Exerc Immunol Rev. 2006;12:6–33.

Benatti FB, Pedersen BK. Exercise as an anti-inflammatory therapy for rheumatic diseases-myokine regulation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:86–97.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the staff members at the Duke Center for Living for their help with training and with recording of data. We appreciate the support of the Division of Rheumatology and Immunology at Duke University. We acknowledge and greatly appreciate all the participants.

Funding

This work was funded by a Duke Department of Medicine Faculty Resident Research Grant (to BJA) and an EU Marie Curie Outgoing Fellowship Grant (to DBB) (PIOF-GA-2013-629981).

Availability of data and materials

Owing to the risk of disclosure or deduction of private individual information, the datasets generated or analyzed (or both) for the present study are not available for public use, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BJA, DBB, VBK, WEK, and KMH conceived and designed the study and experimental approach. DBB, LW, and AH performed the physiological and functional testing and exercise training of participants. KMH performed the skeletal muscle biopsies. JLH completed the plasma galectin-3 and muscle cytokine and myostatin analyses. BJA and KMH performed statistical analyses. BJA wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Pro00064057).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andonian, B.J., Bartlett, D.B., Huebner, J.L. et al. Effect of high-intensity interval training on muscle remodeling in rheumatoid arthritis compared to prediabetes. Arthritis Res Ther 20, 283 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1786-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1786-6