Abstract

Background

In the present study, we explored the effects of immediate induction therapy with the anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α antibody infliximab (IFX) plus methotrexate (MTX) compared with MTX alone and with placebo (PL) in patients with very early inflammatory arthritis.

Methods

In an investigator-initiated, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial (ISRCTN21272423, http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN21272423), patients with synovitis of 12 weeks duration in at least two joints underwent 1 year of treatment with IFX in combination with MTX, MTX monotherapy, or PL randomised in a 2:2:1 ratio. The primary endpoint was clinical remission after 1 year (sustained for at least two consecutive visits 8 weeks apart) with remission defined as no swollen joints, 0–2 tender joints, and an acute-phase reactant within the normal range.

Results

Ninety patients participated in the present study. At week 54 (primary endpoint), 32% of the patients in the IFX + MTX group achieved sustained remission compared with 14% on MTX alone and 0% on PL. This difference (p < 0.05 over all three groups) was statistically significant for IFX + MTX vs PL (p < 0.05), but not for IFX + MTX vs MTX (p = 0.10), nor for MTX vs PL (p = 0.31). Remission was maintained during the second year on no therapy in 75% of the IFX + MTX patients compared with 20% of the MTX-only patients.

Conclusions

These results indicate that patients with early arthritis can benefit from induction therapy with anti-TNF plus MTX compared with MTX alone, suggesting that intensive treatment can alter the disease evolution.

Trial registration

The trial was registered at http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN21272423 on 4 October 2007 (date applied)/12 December 2007 (date assigned). The first patient was included on 24 October 2007.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a severe chronic inflammatory joint disease that can lead to joint damage and functional impairment. Early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can improve outcomes and limit joint damage and irreversible loss of physical function [1,2,3]. With the advent of newer therapeutic agents and treatment strategies [4, 5], the goal of remission is achievable in a proportion of patients [6,7,8]. Importantly, patients in clinical remission usually do not accrue additional joint damage [9, 10]. Despite these benefits of early therapy, drug-free remission is not attainable in the majority of patients [11, 12].

Early in the course of RA, a unique stage called the “window of opportunity” may exist. During this stage, key steps in pathogenesis may be reversible, with DMARD therapy blocking progression to full disease manifestations and potentially leading to sustained remission [13, 14]. Several findings provide support for the window of opportunity hypothesis: an increase in the risk of persistent disease after several months of arthritis symptoms [15, 16]; differences in immunological abnormalities in very early compared with established disease [17, 18]; and the ability of early treatment with a tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor plus methotrexate (MTX) to allow some patients with RA to achieve a drug-free remission [19, 20]. Information on the existence of the window of opportunity on the basis of current data is limited, however, since some studies did not have a double-blind design, evaluated only a very small number of patients and/or were performed only in a single centre. Furthermore, recent data obtained in patients with early disease suggest that, in those fulfilling the classification criteria of RA, drug-free remission after such induction therapy may be uncommon [12, 21].

Very little is known about the pathogenic processes operative in very early inflammatory arthritis, especially in those subjects who do not meet the classification criteria of RA [17, 18, 22]. Since remission due to MTX therapy alone is rare [23], we reasoned that MTX monotherapy might not be sufficient to induce lasting remission, even at this early stage of disease. Moreover, even though the presence of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) has been found to identify subjects at increased risk of progressing to RA [24], we elected not to limit entry to subjects that had developed these biomarkers, but rather to examine a broader group of subjects who had developed unexplained inflammatory arthritis within the past 3 months in order to determine whether the presence of these antibodies or even the classification of RA altered the likelihood of progressing to RA despite intense therapy. The goal of this study, therefore, was to determine whether intense therapy with MTX plus infliximab (IFX) compared with MTX alone or placebo had the capacity to induce long-lasting drug-free remission in subjects with a very short period of inflammatory arthritis symptoms who had not received prior DMARD therapy.

Methods

Study design

The Definitive Intervention in New Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (DINORA) study was a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multi-centre, investigator-initiated trial of the effects of anti-TNFα chimeric monoclonal antibody IFX in combination with MTX in patients with very early inflammatory arthritis and was conducted at 14 rheumatology centres across Europe (three in Austria, four in the Netherlands, four in Germany, and one each in Greece, Italy, and Spain). The study design is depicted in Additional file 1: Figure SA. The trial was registered at http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN21272423. Patient recruitment started in October 2007 and ended in February 2012. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical committees of each institution approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent.

Patients and randomisation

Patients were eligible for the trial if they had symptom duration of 2 to 12 weeks and had synovial swelling present in at least two joints (66 joint count); at least one joint must have been a metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, or metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint; MTP joints only were considered insufficient for inclusion. Baseline visits were scheduled if clinical joint swelling (arthritis) by history was present for 12 weeks and confirmed at two pre-treatment visits between week 2 and week 12 (Additional file 1: Figure SA). Patients with a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test or chest radiograph performed at screening suggesting tuberculosis, malignancy, chronic infectious disease, elevated liver enzymes, or patients who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant within 6 months after the last infusion were excluded. Furthermore, patients with a distinct diagnosis made after a routine diagnostic work-up, such as a connective tissue disease, psoriatic arthritis, gout, pseudogout, reactive arthritis, or parvovirus arthritis, were not eligible. Thus, only patients with undifferentiated arthritis or early RA [25] were enrolled in the trial.

Procedures of the study

Patients were randomised into three groups in a 2:2:1 ratio by a computer generated randomisation list to infliximab plus methotrexate (IFX + MTX), MTX monotherapy (MTX), or placebo (PL). For randomisation, patients were stratified for the use of glucocorticoids (users versus non-users, see below) and the presence of ACPA (> 7 units, measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)) or high titre RF (> 50 IU/ml by nephelometry), determined in a central laboratory. Local investigators were blinded to the results of the central RF and ACPA testing and were also discouraged from having these tests performed on site. For reasons of blinding, a “double-dummy-like” administration of study medication was pursued. Every patient was treated with tablets containing MTX or PL and with infusions containing IFX or PL. The study medication code was kept blinded in patients who discontinued prematurely. Patients were followed until week 106. For rescue therapy for patients who discontinued treatment, the protocol recommended leflunomide (20 mg daily without a loading dose) or sulfasalazine (up to 3000 mg/day) with or without low-dose glucocorticoids.

Patients received treatment with IFX + MTX, MTX alone, or PL. In addition, supportive therapy appropriate at this early stage of arthritis was allowed in all three treatment groups. This therapy included non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and, if necessary, glucocorticoids at a dose of no more than 10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent. MTX was dosed orally according to a rapid dose escalation scheme: treatment was started at 10 mg/week and increased to 25 mg/week in three steps with 2-week intervals except in cases of intolerance. IFX was administered by intravenous infusions at a dose of 3 mg/kg at 0, 2, and 6 weeks, and at 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks thereafter (and thus at higher than the minimal dose approved for maintenance therapy).

All core set variables were assessed at every visit. These variables included swollen and tender joint counts (SJC and TJC; using a 66- and 68-joint count, respectively), patient and evaluator global assessments (PGA and EGA, on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS)), patient pain assessment (by VAS), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; mm/h), C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/dl), American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20, 50, and 70% response rates [26], and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ) [27]. Furthermore, composite measures of disease activity, such as Clinical and Simplified Disease Activity Index (CDAI and SDAI) [28] and Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) using 28-joint counts and ESR [29] were calculated.

Radiographs of hands and feet were taken at baseline, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years and scored independently using the Sharp-van-der-Heijde (SvdH) method [30] by two readers who were blinded to patient characteristics and group allocation but who were aware of the chronological order of the films. The joint space narrowing (JSN) and erosion scores as well as their sum, representing the total score, were evaluated. The average score of the two readers was used for the analyses. In addition, random-effects models were fitted with and without imputation and by taking into account the scores from both readers and the interaction between treatment allocation and study visit to assess if the rate of radiological progression between the three treatment groups was significantly different.

Endpoints

Persistent clinical remission at weeks 46 and 54 compared between all three treatment groups was taken as the primary endpoint. Clinical remission was defined as follows: at two consecutive visits, no swollen joint (66-joint count), 0 to at most 2 tender joints (68-joint count but counting unilateral MTPs as one joint), and a CRP level within the normal range (< 0.5 mg/dl) or a normal ESR (< 25 mm/h). At the time of the study design, the ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) remission criteria [26] had not yet been developed. The criteria chosen here, however, are consistent with these criteria; similar to the Boolean or index-based remission criteria, they do not allow for more than two affected joints (sum of swollen or tender) and require a normal CRP [10, 28].

In all patients, the last infusion of IFX was planned at week 54 (or earlier, as specified below), whereas MTX was continued at the same dose until week 58 and then tapered in all patients over 4 weeks (weekly reduction by 5 mg/week, last dose at week 62). IFX + MTX, MTX, or PL was discontinued earlier if clinical remission was attained at two consecutive visits after the 14-week visit. Thus, for patients who reached clinical remission at two or more consecutive visits before week 54 (sustained remission), IFX (or PL) was stopped and MTX (or PL) tapered beginning after the second visit in remission (first planned possible IFX withdrawal at week 30; Additional file 1: Figure SA). Since the patients would not know on which regimen they had achieved remission, no blinded infusions were continued from that time-point onward. However, as mentioned above, to qualify for the primary endpoint, patients had to have sustained remission until week 54 irrespective of early withdrawal. The study was continued until week 106 without further study medication to evaluate long-term maintenance of remission; blinding of initial treatment assignment remained intact.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation is described in Additional file 2: Supplement S1. Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics and demographic data. We applied a strategy of step-wise hierarchical hypothesis testing [31] to control for type I error of the primary and key secondary (SDAI and DAS28 scores) endpoints. The primary endpoint was analysed at the fixed 46- to 54-week time point (because two visits were needed to define sustained/persistent remission) using Fisher’s exact test. Persistent clinical remission at weeks 46 and 54 was evaluated as a categorical variable (in remission or not) and Fisher’s exact test was calculated for differences over all three treatment groups. For the primary endpoint analysis, we applied non-responder imputation (NRI) for dichotomous variables from those visits onward at which patients had missing data or for patients who started rescue DMARD therapy, and the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method for continuous variables. In case of a significant result regarding the overall difference between all three groups, the primary endpoint was subsequently assessed comparing each of two groups, respectively: group 1 (IFX + MTX) versus 3 (PL), 1 (IFX + MTX) versus 2 (MTX), and 2 (MTX) versus 3 (PL). Longitudinal data analysis of clinical remission is described in Additional file 2: Supplement S2. Secondary endpoints were tested at years 1 and 2 using either Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous data.

Results

Demographic data and patient flow

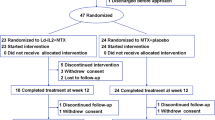

Of the 122 screened patients, 90 were randomised and dosed at the baseline visit (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics and demographic data are described in Table 1. Table 2 depicts the number of patients in clinical remission in the three treatment groups at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. Early withdrawal within the first 3 months was seen in three patients in the IFX + MTX group , in two in the MTX group, and in one patient in the PL group.

Clinical remission at 1 year

At week 54 (primary endpoint), more patients in the IFX + MTX group (12/38, 32%) achieved sustained clinical remission compared with 5/36 (14%) on MTX alone and none (0/16, 0%) on PL. The overall difference across all three treatment groups showed statistical significance (p < 0.05; Additional file 1: Figure SB). Upon subsequent pairwise comparisons, differences in rates of sustained clinical remission were significant between IFX + MTX and PL (treatment effect: 32%; p < 0.05), but not between the IFX + MTX and MTX (treatment effect 18%; p > 0.05), nor between MTX and PL (treatment effect 14%; p > 0.05). Figure 2 shows sustained remission rates as defined for the primary outcome in a cumulative way over time for each of the treatment groups. By week 30, 10 patients (26%) treated with IFX + MTX had already achieved clinical remission at two consecutive visits and all these patients sustained clinical remission until weeks 46 and 54. It is noteworthy that almost one in three patients receiving IFX + MTX, but only one in seven in the MTX group and none on PL had achieved sustained clinical remission at 1 year. The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one additional sustained remission at 52 weeks with IFX + MTX was 3 compared with placebo, while the NNT for MTX alone versus placebo was 7; NNT was 6 when comparing IFX + MTX with MTX alone. The results of the longitudinal data analysis are described in Additional file 2: Supplement S3.

Proportions of remissions; percentage of patients who achieved remission for each time point across the treatment groups. The denominator stays constant, meaning for example in the infliximab (IFX) + methotrexate (MTX) group that the proportion of patients in remission is always divided by 38 (the total number of patients included in this group at baseline). PL placebo

Clinical remission at the end of year 2

Maintenance of a remission state until the end of year 2 differed significantly across the three groups (p = 0.0210); only 20% of patients in remission on MTX monotherapy at 54 weeks maintained remission, whereas this was the case in 75% of those attaining this state on IFX + MTX despite withdrawal of therapy (p = 0.0140 for the comparison between IFX + MTX and MTX groups; Table 2). The NNT to achieve sustained remission at 2 years with IFX + MTX was 2 compared with treatment with MTX alone, and 2 compared with placebo; the NNT for MTX alone versus placebo was 5.

Changes in disease activity and core set variables

At week 54, the proportions of patients with DAS28 < 2.6 and ACR20 responses were significantly different over all three groups (p < 0.01 for DAS28 < 2.6 and p < 0.05 for ACR20), as well as pain scores measured on a VAS (p < 0.05). The stratified differences between treatment groups revealed significance between the IFX + MTX and MTX groups (p < 0.05 for DAS28 < 2.6), IFX + MTX and PL (p < 0.001 for DAS28 < 2.6; p < 0.05 for ACR20; p < 0.05 for pain scores), and between MTX and PL (p < 0.01 for ACR20; p < 0.01 for pain scores).

Patients classified as RA or non-RA at baseline

In the IFX + MTX group, 8/26 (30.8%) of the patients classified as RA [25] achieved clinical remission at the primary endpoint (1 year) compared with 4/12 (33.3%) of the patients who did not fulfil RA classification criteria. In the MTX group, 2/19 (10.5%) of the patients classified as RA reached the primary endpoint at 1 year compared with 3/17 (17.6%) of the patients who did not fulfil RA criteria (data not shown). When looking at the 2-year outcome in the IFX + MTX group, 5/26 (19%) of the patients classified as RA [25] achieved clinical remission compared with 4/12 (33.3%) of the patients who did not fulfil RA classification criteria. In the MTX group, 1/19 (5%) patient classified as RA reached the remission at 2 years compared with none who did not fulfil RA criteria (data not shown). Two of the three patients who were in remission after 2 years in the PL group fulfilled the RA classification criteria at baseline, and all three PL patients were ACPA and RF negative. Thus, there was no difference in outcomes whether patients fulfilled the ACR/EULAR classification criteria [25] or not. The presence of RF made a significant difference in the remission frequency at the 2-year time only point (Chi square test; p = 0.0399); the presence of ACPA made no significant difference in the frequency of remission at 6 months, 1 year, or 2 years.

Radiographic changes

Mean change from baseline of the Sharp-van-der-Heide scores [30] did not reveal any noteworthy differences between the three treatment groups (Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure SC and Table SA).

Adverse events

The occurrences of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) are depicted in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences in the number of patients with AEs between the three treatment groups (Fisher’s exact test; data not shown).

Discussion

The present trial in patients with very early arthritis yields several important findings on the effects of treatment of early inflammatory arthritis with DMARD therapy. First, as in the SAVE trial [32], our study indicated that spontaneous remission (on placebo and supportive treatment alone) occurred only very rarely in patients with undifferentiated arthritis or very early RA of 12 weeks duration. Secondly, we observed that therapy with anti-TNF plus MTX, while significantly different from PL regarding all outcomes, produced more than twice as many stringently defined remissions when compared with MTX alone (32% and 14%, respectively); while the trend was clear, the difference in response rates did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.10). Thirdly, we found that the majority of those patients who had remission on IFX + MTX therapy maintained remission even after withdrawal of all therapies (overall 24% still had clinical remission at 2 years); in contrast, 80% of those on MTX alone lost their remission state, leaving only 3% of MTX-treated patients in remission at 2 years. Fourthly, the vast majority of patients who achieved sustained drug-free remission had already attained this state within 30 weeks, indicating that the necessity for longer treatment durations to achieve remission does not increase drug-free remission rates. Together, these findings suggest that once joint inflammation is clinically manifest, symptomatic therapy does not impact on the course of disease, that initiation of DMARD therapy is warranted to improve outcomes, and that early intensive treatment with anti-TNF + MTX leads to drug-free remission in 1 of 4 patients. When we assessed other remission definitions, such as SDAI or Boolean remission criteria or DAS28 < 2.6, we saw even higher remission rates in the IFX + MTX group at 1 year (34–63%), but this was also the case for the MTX group and the difference across all three groups was not significant, except for DAS28 < 2.6. These findings might be due to the heterogeneity of the patients in our study; furthermore, our data suggest that aggressive therapy is not always necessary in very early inflammatory arthritis for obtaining sustained drug-free remission, although we did not find any respective predictive markers (data not shown).

In addition to delineating the effects of DMARD therapy on early inflammatory arthritis, this study provides important new information on the validity of the window of opportunity hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that a short period of intensive therapy early in the disease course may reverse the disease process and produce long-term benefits. Indeed, in this study, almost one-third of the patients receiving IFX + MTX achieved sustained remission, with 9/12 (75%) of those who attained remission in the first year maintaining this state 1 year later without any treatment (or a total of 9/38 (24%) of the randomised patients). This outcome contrasts with that of patients treated with MTX alone since only 1 in 7 achieved remission in the first year, with the majority subsequently losing this state; as a result, only 3% of patients treated with MTX alone had a sustained remission at 2 years. Thus, anti-TNF + MTX induction treatment demonstrated a clear advantage compared with supportive therapy at 1 year and compared with MTX-only therapy at 2 years; in contrast, induction with MTX alone failed to show a significantly better response than placebo. Importantly, the active therapies, in particular anti-TNF plus MTX, did not appear to cause major serious adverse events in this early arthritis patient population, with the two observed serious adverse events occurring in patients on supportive care.

While one-third of patients treated with IFX + MTX had a favourable outcome, two-thirds of the patients treated with these agents did not attain remission within the first year. This result is disappointing and could argue against the window of opportunity hypothesis. It is important to note, however, that our results pertain only to the combination of IFX + MTX. As shown in other studies, RA patients can differ in their response to biological agents, perhaps based on their mode of action, and we do not know which patients will respond best to a given targeted therapy [33]. On the other hand, the study outcome is quite promising, since 1 of 4 patients with early arthritis did reach drug-free remission after a short course of an induction therapy with these agents. Importantly, in contrast to other randomised controlled trials in early, although established, RA, we did not observe a gradual decline in responders over the second year [21, 34], suggesting a true abrogation or reversal of the disease process.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study may have been underpowered to show a significant difference between the IFX + MTX and MTX-alone groups. For the purposes of this study, we estimated placebo and spontaneous remission rates on the basis of previous observational studies, and the lack of precise data on remission rates from these trials could have led to difficulties in balancing MTX alone and anti-TNF + MTX responses. Although our results indicate that the majority of patients failed to achieve sustained remission on anti-TNF + MTX, the difference between anti-TNF + MTX and MTX alone in the first year might have reached statistical significance with a larger sample size. Of note, in this regard, patients treated with MTX alone did not maintain remission until the end of year 2 while IFX + MTX patients did, suggesting relevant differences in the effects of combination therapy compared with monotherapy. The results of our study need to be interpreted with caution; however, they do suggest that early intensive treatment may alter the course of inflammatory arthritis. One notable unexpected finding was the difficulty of recruiting patients into this study which contrasted with our experience from a previous study [32]. We attempted to enrol very early arthritis patients who had to consent to their participation in a long-term (2 years) study at one of their first visits to the rheumatology centre before many of them had the opportunity to recognise and accept the implications of a diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis and possibly RA. Our experiences may be useful in planning future investigator-driven studies with larger sample sizes in this very early arthritis population of patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides encouraging evidence that a short-term induction therapy with a TNF inhibitor plus MTX can yield long-term benefit in a considerable proportion of patients with early arthritis, even after cessation of all therapy. In contrast, the data presented indicate that MTX alone will not produce responses that are maintained over time. Placebo or supportive treatment alone neither improves nor reverses disease; these findings represent further evidence that spontaneous remission is rare once the signs and symptoms of RA have emerged. While the current study involves only TNF as a target of biological therapy, the data nevertheless strongly support the possibility that patients with early inflammatory arthritis may have a window of opportunity in which disease reversal is possible.

Abbreviations

- ACPA:

-

Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAS28:

-

Disease Activity Score 28

- DINORA:

-

Definitive Intervention in New Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

- EGA:

-

Evaluator global assessment

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- HAQ:

-

Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

- IFX:

-

Infliximab

- MTP:

-

metatarsophalangeal

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- NNT:

-

Number needed to treat

- PGA:

-

Patient global assessment

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- SDAI:

-

Simplified Disease Activity Index

- SJC:

-

Swollen joint count

- TJC:

-

Tender joint count

- TNF:

-

Tumour necrosis factor

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

van der Heide A, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW, Heurkens AH, van Booma-Frankfort C, van der Veen MJ, Haanen HC, Hofman DM, van Albada-Kuipers GA, ter Borg EJ, et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(8):699–707.

Nell VK, Machold KP, Eberl G, Stamm TA, Uffmann M, Smolen JS. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004; Epub (ahead of print)

Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, vander Horst-Bruinsma IE, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, Hazes J. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. AmJMed. 2001;111(6):446–51.

Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, Vallance R, Kincaid W, Porter D. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–9.

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Kerstens PJ, Nielen MM, Vos K, van Schaardenburg D, Speyer I, Seys PE, Breedveld FC, Allaart CF, et al. DAS-driven therapy versus routine care in patients with recent-onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):65–9.

Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, Moreland LW, O'Dell J, Winthrop KL, Beukelman T, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(5):625–39.

Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, Nam J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):492–509.

Mierau M, Schoels M, Gonda G, Fuchs J, Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology(Oxford). 2007;46(6):975–9.

Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, Aletaha D, Allaart CF, Bathon J, Bombardieri S, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):404–13.

Aletaha D, Funovits J, Breedveld FC, Sharp J, Segurado O, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid arthritis joint progression in sustained remission is determined by disease activity levels preceding the period of radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1242–9.

Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Mimori T, Saito K, Nawata M, Kameda H, Nojima T, Miyasaka N, Koike T, investigators RRRs. Discontinuation of infliximab after attaining low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: RRR (remission induction by Remicade in RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(7):1286–91.

Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O, Combe B, Martin-Mola E, Buch MH, Krogulec M, Williams T, Gaylord S, Pedersen R, et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1781–92.

Furst DE. Window of opportunity. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(9):1677–9.

Raza K, Saber TP, Kvien TK, Tak PP, Gerlag DM. Timing the therapeutic window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: proposal for definitions of disease duration in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(12):1921–3.

Green M, Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, Wakefield R, Proudman S, Conaghan P, Gooi J, Emery P. Persistence of mild, early inflammatory arthritis: the importance of disease duration, rheumatoid factor, and the shared epitope. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(10):2184–8.

van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza K, van der Woude D, Knevel R, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(12):3537–46.

Raza K, Falciani F, Curnow SJ, Ross EJ, Lee CY, Akbar AN, Lord JM, Gordon C, Buckley CD, Salmon M. Early rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by a distinct and transient synovial fluid cytokine profile of T cell and stromal cell origin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(4):R784–95.

de Hair MJ, van de Sande MG, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Hansson M, Landewe R, van der Leij C, Maas M, Serre G, van Schaardenburg D, Klareskog L, et al. Features of the synovium of individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: implications for understanding preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(3):513–22.

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, Peeters AJ, de Jonge-Bok JM, Mallee C, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(6):406–15.

Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O'Connor PJ, Karim Z, Greenstein A, Brown A, Brown C, Fraser A, Jarret S, Emery P. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal: results from a twelve-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):27–35.

Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Combe BG, Furst DE, Barre E, Karyekar CS, Wong DA, Huizinga TW. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):19–26.

Choi IY, Karpus ON, Turner JD, Hardie D, Marshall JL, de Hair MJ, Maijer KI, Tak PP, Raza K, Hamann J. Stromal cell markers are differentially expressed in the synovial tissue of patients with early arthritis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182751.

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, Ronday HK, Han KH, Westedt ML, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3381–90.

Visser H, le Cessie S, Vos K, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. How to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis early: a prediction model for persistent (erosive) arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(2):357–65.

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO III, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. AnnRheumDis. 2010;69(9):1580–8.

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:727–35.

Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–45.

Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, Nell VP, Stamm T, Smolen JS. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2625–36.

Prevoo ML, 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8.

van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):261–3.

Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, Ludivico C, Krogulec M, Xie L, Beattie SD, Koch AE, Cardillo TE, Rooney TP, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1243–52.

Machold KP, Landewe R, Smolen JS, Stamm TA, van der Heijde DM, Verpoort KN, Brickmann K, Vazquez-Mellado J, Karateev DE, Breedveld FC, et al. The stop arthritis very early (SAVE) trial, an international multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on glucocorticoids in very early arthritis. AnnRheumDis. 2010;69(3):495–502.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(5):276–89.

Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, Singh A, Pedersen RD, Koenig AS, Freundlich B. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to all patients who participated in the present study and to the members of the drug safety monitoring board, Hans Bijlsma, Wolfgang Graninger, Hans Hillege, and Frank Wollheim.

Funding

DINORA was designed by the sponsor, the Department of Medicine 3, Medical University of Vienna (MUV), Austria, in collaboration with an international advisory committee. The data were analysed by the sponsor and the Clinical Trial Coordination Center (TCC) in Groningen, The Netherlands. Funds for the planning of the trial were provided by NIH grants AR050880 and AR052465 to DP. The study was funded by a grant from Janssen (previously Centocor). Janssen participated in the design of the protocol and the review of the report. All authors participated in collection and/or interpretation of the data, contributed substantially to the manuscript, and agreed to submit it for publication. All investigators at MUV had full access to the data and vouch for accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses. Individual author disclosures are listed below.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KPM, DA, RL, DvdH, MA, DB, GB, MC, WE, WG, TH, GS, HSK, PPT, EMM, and FB were involved in the planning of the study, recruited patients, and participated in writing, reviewing and approval of the analysis and the final manuscript. JS, FA, PL, DP, AS, and TAS were involved in the planning of the study, conducted clinical trial and/or data logistics, performed the data analyses or parts of it and wrote and approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The EudraCT number is 2006–002787-26 and the protocol number from the ethical committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, that first approved the protocol is 292/2006. Ethical committees of each institution approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

The present manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data, such as individual details, images, or videos.

Competing interests

TAS has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, and Roche and grant support from AbbVie. MAS has received speaker fees from MSD. KPM has received money from AbbVie (speaker’s fees, consulting fees, research grant), Astro (speaker’s fees, consulting fees), Baxter (consulting fees), BMS (speaker’s fees), Celgene (speaker’s fees), Janssen-Cilag (speaker’s fees), Lilly (speaker’s fees), MSD (speaker’s fees), Novartis (speaker’s fees, consulting fees), Pfizer (speaker’s fees), Roche (speaker’s fees), UCB (speaker’s fees), Arsanis (consulting fees), and Sandoz (speaker’s fees). DA has served as a consultant for and/or received grant/research support from AbbVie, Pfizer, Grünenthal, Merck Medac, UCB, Mitsubishi/Tanabe, Janssen, and Roche. PL received consulting fees from Janssen, EMD Serono, Astra Zeneca, UCB, Roche, Celgene, Sanofi, and Horizon, but none of them relates to the content of this manuscript. RL has received fees for consultation or participation in advisory boards by Abbott/AbbVie, Ablynx, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen (formerly Centocor), Galapagos, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, TiGenix, UCB, and Wyeth; research grants from Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB and Wyeth and speaker fees from Abbott/AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen (formerly Centocor), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB, and Wyeth; furthermore, RL is director of Rheumatology Consultancy BV which is a registered company under Dutch law. DvdH has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boeringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Daiichi, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB and is director of Imaging Rheumatology BV. MA has received advisory Boards and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Chugai, GSK, Hexal, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB; his institution is clinical trial site for AbbVie, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. GB has received speaker fees from MSD, UCB and Roche and research funds from AbbVie, BMS, UCB, and Roche. MC has received speaker fees from Biogen, Mundipharm, Pfizer and Menarini and research funds from BMS, Horizon, Actelion, Celgene, and MSD. WE has received consulting fees from Novartis and Abbvie. TH has received lecture fees/consultancy fees from Merck, UCB, Bristol Myers Squibb, Biotest AG, Pfizer, GSK, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbott, Crescendo Bioscience, Nycomed, Boeringher, Takeda, Epirus, and Eli Lilly. GS has received speaker fees from BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Lilly, Roche, and UCB. HSK has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Actelion, AstraZeneca, Biogen International, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Cinfa Biotech, GSK, Hospira, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, MSD, Medac, Merck, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Hexal Sandoz, Roche, and UCB. PPT has become an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. GSK has not been involved in this study. JS has received grants for his institution from Abbvie, Lilly, MSD, Pfizer and Roche and has provided remunerated expert advice to and/or had speaking engagements for Abbvie, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Astro, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Gilead, Glaxo, ILTOO, Janssen, Lilly, Medimmune, MSD, Novartis-Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sanofi, and UCB. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supplemental figures SA and SB. (PPTX 101 kb)

Additional file 2:

Supplemental files. (DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Stamm, T.A., Machold, K.P., Aletaha, D. et al. Induction of sustained remission in early inflammatory arthritis with the combination of infliximab plus methotrexate: the DINORA trial. Arthritis Res Ther 20, 174 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1667-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1667-z