Abstract

Background

Registry studies provide a valuable source of comparative safety data for tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) used in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but they are subject to channeling bias. Comparing safety outcomes without accounting for channeling bias can lead to inaccurate comparisons between TNFi prescribed at different stages of the disease. In the present study, we examined the incidence of serious infection and other adverse events during certolizumab pegol (CZP) use vs other TNFi in a U.S. RA cohort before and after using a methodological approach to minimize channeling bias.

Methods

Patients with RA enrolled in the Corrona registry, aged ≥ 18 years, initiating CZP or other TNFi (etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, or infliximab) after May 1, 2009 (n = 6215 initiations), were followed for ≤ 12 months. A propensity score (PS) model was used to control for baseline characteristics associated with the probability of receiving CZP vs other TNFi. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of serious infectious events (SIEs), malignancies, and cardiovascular events (CVEs) in the CZP group vs other TNFi group were calculated with 95% CIs, before and after PS matching.

Results

Patients were more likely to initiate CZP later in the course of therapy than those initiating other TNFi. CZP initiators (n = 975) were older and had longer disease duration, more active disease, and greater disability than other TNFi initiators (n = 5240). After PS matching, there were no clinically important differences between CZP (n = 952) and other TNFi (n = 952). Before PS matching, CZP was associated with a greater incidence of SIEs (IRR 1.53 [95% CI 1.13, 2.05]). The risk of SIEs was not different between groups after PS matching (IRR 1.26 [95% CI 0.84, 1.90]). The 95% CI of the IRRs for malignancies or CVEs included unity, regardless of PS matching, suggesting no difference in risk between CZP and other TNFi.

Conclusions

After using PS matching to minimize channeling bias and compare patients with a similar likelihood of receiving CZP or other TNFi, the 1-year risk of SIEs, malignancies, and CVEs was not distinguishable between the two groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes persistent synovial inflammation. When not treated adequately, active RA can lead to progressive joint damage, significant pain, disability, and reduced quality of life [1, 2]. The chronic inflammation inherent to RA has consequences that go beyond the damage to the musculoskeletal system. Compared with the general population, RA is associated with substantial morbidity and premature mortality, which is attributed mainly to serious infection, cardiovascular disease, and certain types of cancer [3,4,5]. The substantial disease burden of RA underscores the importance of effective therapy.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), often the first class of biologic therapy prescribed to patients with RA, have been demonstrated to reduce disease activity and improve clinical, radiographic, and functional outcomes [6]. Effective control of disease activity with TNFi has been linked with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease [7, 8]. Conversely, the immunosuppressive effect of TNFi has raised concerns over an increased risk of infection [9], although the magnitude of this risk remains a topic of intense debate [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The impact of TNFi on the incidence of cancer is also unclear [11, 22,23,24,25].

Overall, it is difficult to assess the risks associated with TNFi therapy, owing to the influence of patients’ demographic characteristics, clinical history, and concomitant immunomodulatory treatments. Furthermore, in clinical practice, drugs with similar therapeutic indications can be prescribed selectively to patients with different baseline prognoses, a phenomenon termed channeling bias [26]. Consequently, the line of TNFi therapy may also influence the safety risks observed in clinical practice.

Certolizumab pegol (CZP), a PEGylated, Fc-free TNFi, is approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe active RA [27]. Currently, there is limited evidence on the safety of CZP compared with other TNFi drugs in the context of U.S. clinical practice. The objective of this prospective, observational cohort study was to examine the 1-year incidence of serious infectious events (SIEs) during CZP use compared with other TNFi drugs (golimumab, etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab), with and without a methodological approach accounting for channeling bias in patients with moderate to severe RA enrolled in the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (Corrona) registry. The 1-year risk of malignancies and cardiovascular events (CVEs) was also assessed, owing to their importance for decision-making in clinical practice.

Methods

Data source

The Corrona registry is an independent, prospective, observational cohort of patients with RA recruited from 169 private and academic practice sites across 40 states in the United States [28]. Data on 43,099 patients with RA had been collected as of June 30, 2016. The Corrona database comprises information from 326,613 patient visits and approximately 145,526.5 patient-years (PY) of total follow-up, with a mean patient follow-up of 4.13 years, and median time between follow-up visits of 4.90 months. Institutional review board (IRB) approvals for this study were obtained from a central IRB (New England IRB) for private practice sites and local IRBs of participating academic sites.

Study population

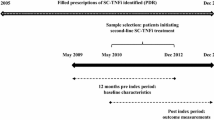

Data were provided by treating rheumatologists for patients with RA enrolled in the Corrona registry who initiated treatment with CZP or other TNFi (adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab) between May 1, 2009, and March 31, 2016. Patients could have been treated with TNFi before this study, so index drug corresponded to any line of therapy. If patients were treated with more than one TNFi during the study, all TNFi initiations were included in the analysis. The study population comprised patients aged ≥ 18 years with at least one follow-up visit post-drug initiation. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Adverse events of interest

Physician-reported adverse events (AEs) of interest that occurred from drug initiation up to 90 days following discontinuation/switch of TNFi, or up to 12 months from drug initiation, were included in the analysis. SIEs were the main AE of interest (infections requiring hospitalization and/or intravenous antibiotics); when data were available, information was also provided about the SIE microorganism (opportunistic vs nonopportunistic), malignancies, and CVEs (Table 1).

Other AEs of interest included anaphylaxis/allergic reaction, drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, gastrointestinal perforation, hepatic events, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, other neurological events with hospitalization and/or other demyelinating disease, and spontaneous serious bleeding (see Additional file 1: Table S1). Corrona has an established system for the validation of physician-reported AEs. Briefly, serious AEs and AEs of special interest are recorded by treating physicians using Targeted Adverse Event questionnaires. These questionnaires, alongside supporting documents appropriate to the event (e.g., hospitalization records, pathology reports), are submitted to Corrona for validation, with a subset triaged for expert adjudication. Previous validation of Corrona’s AE reporting has found positive predictive values of 86% for malignancies [29], 96% for CVEs [30], and 71% for SIEs [31].

Propensity score matching

To control for baseline patient characteristics associated with the likelihood of receiving CZP or an alternative TNFi, a propensity score (PS; i.e., the probability of treatment selection) was calculated for each patient using a logistic regression model that included baseline covariates with p < 0.1 for the difference between CZP and other TNFi and thought to be independently associated with treatment on the basis of clinical expertise and prior group consensus. CZP and other TNFi patients were matched by estimated PS from a model including age, sex, disease duration, Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) at drug initiation, and physician-reported line of TNFi therapy. Matching was performed in a 1:1 ratio without replacement, using a maximum tolerated difference (caliper) of 0.01.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ comorbidity scores were calculated using a modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index [32] (see Additional file 1). All patients had a modified Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 1 because RA is included under connective tissue disease.

Baseline characteristics were compared between CZP and other TNFi patients before and after PS matching. Student’s two-sample t tests were used for continuous variables (or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests if variables were skewed), and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (or Fisher’s exact test in the case of small counts). All p values were nominal in nature and should be interpreted in an exploratory manner.

Observed incidence rates (IRs) of AEs of interest were calculated per 100 PY, with 95% CIs calculated using the Poisson distribution assumption. For each AE category, time at risk was measured from drug initiation up to either the occurrence of the first event of interest under that category, 90 days following discontinuation/switch of biologic (censored), or up to 12 months after drug initiation (censored). Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated in both unmatched and PS-matched comparisons for overall SIEs, malignancies, and CVEs, with CZP as numerator and other TNFi as denominator; 95% CIs were calculated using the exact distribution derived using Stata® version 14.1 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Baseline demographics

A total of 5363 patients with RA in the Corrona database met the inclusion criteria and initiated TNFi therapy between May 1, 2009, and March 31, 2016. There were a total of 6215 TNFi initiations comprising 975 CZP initiators and 5240 initiators of other TNFi (adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab). After PS matching, the CZP and other TNFi groups included 952 patients each (Fig. 1).

Patient disposition. Data from May 1, 2009, through March 31, 2016, were available. There were 975 unique CZP patients and 4625 unique other TNFi patients. aEligible patients with RA were ≥ 18 years of age, had at least one follow-up visit post-index drug initiation, and provided written informed consent prior to participation. bInitiations refer to the total number of TNFi initiated during the period of observation because patients may have used more than one TNFi during the study (e.g., if one patient switched from etanercept to CZP, both initiations would have been included in the analysis). cPropensity scores were calculated using a logistic regression model fitted with the following baseline covariates: age, sex, disease duration, CDAI at initiation, and TNFi line of therapy. RA rheumatoid arthritis, CZP certolizumab pegol, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, IV intravenous, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index

Among all initiators (before PS matching), on average, patients initiating CZP were older, had longer disease duration, had more active disease based on the CDAI, and had more functional impairment based on the modified Health Assessment Questionnaire than patients in the other TNFi group (p ≤ 0.01) (Table 2). Race and Medicare insurance status also showed an imbalance between the two groups (p < 0.001). Sex, body mass index (BMI), age at RA onset, and the prevalence of comorbidities were balanced between groups (Table 2), as were rheumatoid factor positivity, anticitrullinated protein antibody positivity, smoking status, and blood pressure (not shown). Patients were more likely to initiate CZP later in the course of therapy, with approximately 44.8% of CZP initiators corresponding to third-line therapy or later, compared with 20.1% in the other TNFi group (Table 2). Concomitant disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and prednisone use were similar between the two groups, except for methotrexate (MTX) and other nonbiologic DMARD use, which was more prevalent among other TNFi initiators (Table 2).

After PS matching, there were no clinically relevant baseline differences between the CZP and other TNFi groups; line of TNFi therapy and concomitant medication use were also similar (Table 2).

Observed incidence of AEs in the unmatched population

Average follow-up for each of the AEs can be calculated as the number of PY at risk divided by the number of patients considered. For instance, with SIEs in the CZP group, the average follow-up time was 820/975 = 0.84 PY (approximately 10 months).

Among all initiators, the IR of SIEs was higher in the CZP group than in the other TNFi group (Table 3). The 95% CI of the corresponding IRR excluded unity (IRR 1.53 [1.13, 2.05]), suggesting that CZP was associated with a greater risk of SIEs than other TNFi (Fig. 2a). By contrast, the IRs of malignancies and CVEs did not differ substantially between CZP and other TNFi (Table 3). The 95% CI of the IRRs for malignancies (IRR 0.86 [0.46, 1.49]) and CVEs (IRR 1.22 [0.67, 2.08]) included unity, suggesting no difference in risk between the two groups (Fig. 2a).

IRRs of SIEs, malignancies, and CVEs between the CZP and other TNFi groups. a Before PS matching (all initiators). b After PS matching. IRRs were calculated with the CZP group in the numerator and the other TNFi in the denominator. IRR Incidence rate ratio, SIE Serious infectious event, CVE Cardiovascular event, CZP Certolizumab pegol, TNFi Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, PS Propensity score

Cellulitis/skin infection, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection were the most frequently reported SIEs. There were no cases of active tuberculosis among CZP initiators, and there were two cases in the other TNFi group (Table 3). Regarding other AEs of interest, rare cases of anaphylaxis/allergic reaction were reported for both CZP (4 events) and other TNFi (14 events). Patients in the other TNFi group also reported gastrointestinal perforation (three events), hepatic events (ten events), other neurological events (four events), and spontaneous serious bleeding (five events) (Table 3).

Observed incidence of AEs in the PS-matched population

In contrast with the unmatched population, the IR of SIEs was similar between CZP and other TNFi after PS matching (Table 4). The 95% CI of the IRR included unity (IRR 1.26 [0.84, 1.90]), suggesting that the risk of SIEs was not different between the PS-matched groups (Fig. 2b). Similar to what was seen in the unmatched population, the IRs of malignancies and CVEs in the CZP and other TNFi groups did not differ substantially after PS matching (Table 4). The 95% CI of the IRRs for malignancies (IRR 0.71 [0.33, 1.47]) and CVEs (IRR 1.01 [0.49, 2.11]) included unity, suggesting no difference in risk between the PS-matched groups (Fig. 2b).

Cellulitis/skin infection, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection were still the most frequent SIEs. The incidence rates of other AEs of interest remained low in the PS-matched groups (Table 4).

Discussion

When initiating TNFi therapy in RA, rheumatologists need to carefully balance the potential clinical benefits of treatment with the anticipated risks in each individual patient in light of their demographic characteristics, clinical history, and concomitant medications. Excepting a recently completed head-to-head randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the efficacy and safety of CZP and adalimumab, in which investigators reported no clinically significant differences between the two drugs [33], there is a paucity of head-to-head RCTs comparing the safety of TNFi drugs in RA. Observational studies therefore provide a valuable source of comparative safety data.

Using data from the Corrona registry, we compared the safety of CZP with other TNFi as a group (golimumab, etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab). As with any registry study, channeling bias can arise from the fact that clinicians prescribe treatment not at random but based on personal clinical experience and their patients’ clinical characteristics [26]. To overcome this limitation, we assessed safety outcomes in two cohorts: (1) all patients initiating CZP or other TNFi therapy and (2) the subset of patients matched by PS. In the unmatched population, the rate of SIEs was approximately 50% higher in the CZP group than in the other TNFi group. After using the PS-matched model to minimize channeling bias and resolve clinically significant baseline differences between CZP and other TNFi initiators, the risk of SIEs associated with each group was no longer distinguishable.

The contrasting results in the unmatched and PS-matched cohorts highlight the need to consider baseline patient differences when comparing the risk of AEs between TNFi drugs prescribed at different stages in the course of RA. CZP was prescribed later in the line of therapy than other TNFi. Consequently, patients initiating CZP were, on average, older and had longer disease duration, more active disease, and more functional impairment than patients initiating treatment with other TNFi. This probably explains the higher rate of SIEs in the unmatched CZP group because older age, high disease activity, and disability have previously been identified as risk factors for serious infection in RA [9, 34,35,36,37,38].

Meta-analyses of RCTs have demonstrated that the different TNFi drugs available in RA are equally efficacious at reducing disease activity [18]. Therefore, on the basis of clinical efficacy alone, there has been relative equipoise among rheumatologists regarding which therapy to choose as first and subsequent lines of treatment [39]. However, the safety of TNFi therapy, particularly with regard to infection, continues to be debated. The authors of the first published meta-analysis of serious infection in RA detected an association with TNFi treatment [11], but subsequent meta-analyses performed with greater sample sizes have produced discordant results [14, 15, 17, 18, 20]. Similarly, whereas researchers in some observational studies have reported an association between TNFi and the risk of serious infection [10, 13, 19], others did not find a clear link [12, 16, 21]. In a large meta-analysis of RCTs in which authors compared the safety of all five TNFi drugs across multiple diseases, CZP was associated with higher odds of serious infection than adalimumab, etanercept, and golimumab [40]. However, the diseases and patient populations captured in this meta-analysis differed substantially between drugs, and no correction was made for placebo exposure, which makes the results difficult to interpret. It is known that the background risk of SIEs varies greatly across diseases [37, 41], and even within indications it is strongly dependent on study inclusion criteria and baseline patient characteristics [35]. By contrast, a recent head-to-head clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of CZP with adalimumab in patients with RA provided direct evidence of a comparable safety profile for the two drugs, including a similar incidence of serious infection [33].

The IRs of SIEs reported in the present study are consistent with rates observed in other real-world patient populations. For example, in a retrospective study of medical and pharmaceutical data from a large U.S. health insurer, the rate of hospitalized infections among patients with RA with no prior biologic use was 4.6/100 PY, whereas for patients switching to a new biologic at baseline, an IR of 7.0/100 PY was reported [35]. In a retrospective analysis of Medicare claims data for patients with RA treated with prior biologics, the crude IRs of hospitalized infection during TNFi treatment ranged between 14.1/100 PY (golimumab) and 17.0/100 PY (infliximab; the IR for CZP was 14.2/100 PY) [42]. A prospective observational study using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register – Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) reported rates of SIEs ranging from 2.8/100 PY in patients aged < 55 years to 8.3/100 PY in patients aged > 75 years [13].

Regardless of PS matching, there were no important differences in the IRs of malignancies and CVEs between CZP and other TNFi initiators. Interpretation of these results must take into account the infrequent nature of these AEs and the fact that patients in this study were followed for a maximum of 12 months, which may have been too short to detect meaningful risk differences between groups.

Evaluating the impact of TNFi on the risk of cancer in RA is a challenging task. Because most types of cancer occur very rarely, RCTs often lack sufficient power to conclusively assess the risk of malignancy, owing to the short duration of follow-up. Furthermore, patients with RA with a history of cancer tend to be excluded from participation in RCTs [43]. Given the latency of cancer and its potential for reactivation over time, it is important to evaluate the risks of TNFi use in patients with a history of this condition. Approximately 5% of Corrona patients included in our study had a history of prior malignancy. Regardless of PS matching, the IRs of malignancies reported here for CZP and other TNFi initiators were comparable to those previously reported in the BSRBR-RA [43, 44] and the Swedish Biologics Registry [45]. Also consistent with these two registries, nonmelanoma skin cancer was one of the most commonly reported malignancies [46, 47].

Cardiovascular disease is one of the main causes of morbidity and premature mortality in patients with RA [3]. This has been attributed to the direct impact of chronic inflammation on the vascular system and to the secondary effects of physical inactivity [48]. By effectively reducing disease activity, TNFi treatment may help to mitigate the cardiovascular risk associated with RA [7, 8]. In this study, traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as BMI, smoking status, blood pressure, history of cardiovascular disease, and prednisone use were similar at drug initiation between the CZP and other TNFi groups. By contrast, RA disease activity, which is also associated with cardiovascular risk [8, 49, 50], was higher in the CZP group. Nevertheless, the IRs of CVEs we report, which corresponded mainly to myocardial infarction and transient ischemic attack (TIA)/stroke, did not differ substantially between the CZP and other TNFi groups, regardless of PS matching.

A limitation of this study was that patients were followed for a maximum of 12 months after initiation of a particular TNFi. Although SIE rates tend to be highest during the first 6–12 months of TNFi exposure [13, 51], this time frame may not have been sufficient to detect differences in the rates of CVEs or malignancies, owing to the comparative infrequency and longer-term nature of these AEs. Despite this limitation, the rates of malignancy we report were consistent with a recent meta-analysis of observational studies where there were no differences among the five TNFi drugs regarding the overall risk of cancer [52]. Similarly, the rates of myocardial infarction and TIA/stroke were comparable to those previously reported for the Corrona cohort [8]. The rarity of other AEs of interest prevented further analyses; their inclusion in this report was meant to provide a more complete picture of the AEs reported by the study population. Overall, although AEs were assessed over a 1-year period only, the findings of this study are consistent with previously published long-term safety analyses of CZP in RA [53].

A key strength of this study is the fact that we compared safety outcomes for TNFi in U.S. clinical practice using data from a large, nationwide cohort of patients with RA. Because patient characteristics and access to biologic drugs can vary substantially between countries, owing to payer and regulatory differences, it is important to obtain clinical evidence directly relevant to practicing rheumatologists in the United States. It has been demonstrated that patients in Corrona share similar demographic and clinical characteristics with Medicare beneficiaries with claims for rheumatology or RA, suggesting that the results we present may be generalizable to the wider RA population in the United States [54]. Furthermore, we used PS matching to control for baseline patient characteristics that might have influenced the decision to treat with CZP or other TNFi, thereby helping to minimize channeling bias and allowing for a more accurate comparison of the risk of AEs associated with these therapies.

Conclusions

In a PS-matched cohort of patients with moderate to severe RA enrolled in the Corrona registry, there were no differences in the 1-year risk of SIEs, malignancies, and CVEs between patients treated with CZP and those treated with other TNFi.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BSRBR-RA:

-

British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register – Rheumatoid Arthritis

- CDAI:

-

Clinical Disease Activity Index

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Corrona:

-

Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America

- CVE:

-

Cardiovascular event

- CZP:

-

Certolizumab pegol

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug

- IR:

-

Incidence rate

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- mHAQ:

-

Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- NC:

-

Not calculable

- NMSC:

-

Nonmelanoma skin cancer

- PS:

-

Propensity score

- PY:

-

Patient-years

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SIE:

-

Serious infectious event

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Kvien TK. Epidemiology and burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(2 Suppl 1):1–12.

Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010;376(9746):1094–108.

Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1690–7.

Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, et al. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2287–93.

Naz SM, Symmons DP. Mortality in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(5):871–83.

Nam JL, Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):516–28.

Barnabe C, Martin BJ, Ghali WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(4):522–9.

Solomon DH, Reed GW, Kremer JM, et al. Disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of cardiovascular events. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1449–55.

Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(1):53–61.

Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, et al. Time-dependent increase in risk of hospitalisation with infection among Swedish RA patients treated with TNF antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(10):1339–44.

Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(19):2275–85.

Dixon WG, Symmons DP, Lunt M, et al. Serious infection following anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from interpreting data from observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2896–904.

Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, et al. Anti-TNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register with special emphasis on risks in the elderly. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(1):124–31.

Leombruno JP, Einarson TR, Keystone EC. The safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatments in rheumatoid arthritis: meta and exposure-adjusted pooled analyses of serious adverse events. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1136–45.

Salliot C, Dougados M, Gossec L. Risk of serious infections during rituximab, abatacept and anakinra treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(1):25–32.

Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Weinblatt ME, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy and the risk of serious bacterial infections in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):1754–64.

Singh JA, Cameron C, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Risk of serious infection in biological treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):258–65.

Singh JA, Hossain A, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Biologics or tofacitinib for rheumatoid arthritis in incomplete responders to methotrexate or other traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5:CD012183.

Strangfeld A, Eveslage M, Schneider M, et al. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time-dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1914–20.

Thompson AE, Rieder SW, Pope JE. Tumor necrosis factor therapy and the risk of serious infection and malignancy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1479–85.

Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K. Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia: associations with prednisone, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(2):628–34.

Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, et al. Risks of solid cancers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and after treatment with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(10):1421–6.

Bongartz T, Warren FC, Mines D, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancies: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1177–83.

Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(4):517–24.

Wong AK, Kerkoutian S, Said J, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients receiving antitumor necrosis factor therapy: a meta-analysis of published randomized controlled studies. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(4):631–6.

Petri H, Urquhart J. Channeling bias in the interpretation of drug effects. Stat Med. 1991;10(4):577–81.

FDA. Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) Prescribing Information; last updated April 2016. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125160s241lbl.pdf. Last accessed: September 2016.

Kremer JM. The CORRONA database. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S172–7.

Fisher MC, Furer V, Hochberg MC, et al. Malignancy validation in a United States registry of rheumatoid arthritis patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:85.

Solomon DH, Kremer J, Curtis JR, et al. Explaining the cardiovascular risk associated with rheumatoid arthritis: traditional risk factors versus markers of rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1920–5.

Curtis JR, Patkar NM, Jain A, et al. Validity of physician-reported hospitalized infections in a US arthritis registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(10):1269–72.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Combe B, et al. Head-to-head comparison of certolizumab pegol versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year efficacy and safety results from the randomised EXXELERATE study. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2763–74.

Au K, Reed G, Curtis JR, et al. High disease activity is associated with an increased risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):785–91.

Curtis JR, Xie F, Chen L, et al. The comparative risk of serious infections among rheumatoid arthritis patients starting or switching biological agents. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(8):1401–6.

Emery P, Gallo G, Boyd H, et al. Association between disease activity and risk of serious infections in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept or disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(5):653–60.

Grijalva CG, Chen L, Delzell E, et al. Initiation of tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists and the risk of hospitalization for infection in patients with autoimmune diseases. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2331–9.

Weaver A, Troum O, Hooper M, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity and disability affect the risk of serious infection events in RADIUS 1. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(8):1275–81.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges Jr SL, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26.

Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD008794.

Burmester GR, Mease P, Dijkmans BA, et al. Adalimumab safety and mortality rates from global clinical trials of six immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1863–9.

Yun H, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Comparative risk of hospitalized infection associated with biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in Medicare. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):56–66.

Silva-Fernández L, Lunt M, Kearsley-Fleet L, et al. The incidence of cancer in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a prior malignancy who receive TNF inhibitors or rituximab: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register-Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):2033–9.

Morgan CL, Emery P, Porter D, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with etanercept with reference to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: long-term safety and survival using prospective, observational data. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(1):186–94.

Askling J, van Vollenhoven RF, Granath F, et al. Cancer risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapies: does the risk change with the time since start of treatment? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3180–9.

Mercer LK, Green AC, Galloway JB, et al. The influence of anti-TNF therapy upon incidence of keratinocyte skin cancer in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: longitudinal results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):869–74.

Raaschou P, Simard JF, Holmqvist M, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis, anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy, and risk of malignant melanoma: nationwide population based prospective cohort study from Sweden. BMJ. 2013;346:f1939.

Turesson C. Comorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14290.

Del Rincon I, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. Association between carotid atherosclerosis and markers of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(7):1833–40.

Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Lipid paradox in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of serum lipid measures and systemic inflammation on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):482–7.

Cobo-Ibanez T, Descalzo MA, Loza-Santamaria E, et al. Serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated connective tissue diseases exposed to anti-TNF or rituximab: data from the Spanish registry BIOBADASER 2.0. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(7):953–61.

Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Nam JL, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):529–35.

Bykerk VP, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):96–103.

Curtis JR, Chen L, Bharat A, et al. Linkage of a de-identified United States rheumatoid arthritis registry with administrative data to facilitate comparative effectiveness research. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(12):1790–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers, in addition to the investigators and their teams, who contributed to this study. The authors acknowledge Ricardo Milho, PhD, and Aimée Hall, MPhys, Costello Medical Consulting, Cambridge, UK, for writing and editorial assistance. All costs associated with the development of this article were funded by UCB Pharma.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Corrona, LLC. Corrona, LLC has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last 2 years by AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Horizon Pharma USA, Janssen, Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., Roche, Sun-Merck, UCB Pharma, and Valeant. Support for third-party writing assistance for this article, provided by Ricardo Milho, PhD, and Aimée Hall, MPhys, Costello Medical Consulting, Cambridge, UK, was funded by UCB Pharma.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Corrona, LLC, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the present study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Corrona, LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LRH, HJL, KCS, KJD, BG, JDG, RL, JS, RS, SJ, JMK, and MY contributed to the conception, design, execution or analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors approved the final version to be published after critically revising the manuscript/publication for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting noninterventional research involving human subjects with a limited dataset. Sponsor approval and continuing review were obtained through a central institutional review board (IRB) (New England Independent Review Board; NEIRB number 02-021). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to the sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. The principal investigator or designee at each site inform patients of the purposes of this registry. Patients who express a willingness to consider participation are given a consent form to review. If patients have any questions related to participation in the registry, these are answered by the principal investigator or designee. Patients sign the voluntary consent form. Patients who consent to participate in the registry receive a signed and dated copy of the consent form. Informed consent must be obtained before any assessments are performed.

Consent for publication

All the results presented in this article are in aggregate form, and no personally identifiable information was used for this study.

Competing interests

LRH has received research grants from Pfizer; stock from Corrona, LLC; consulting fees from Roche and Bristol Myers-Squibb; and is an employee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Corrona, LLC. HJL is an employee of Corrona, LLC. KCS is an employee of Corrona, LLC. KJD is an employee of Corrona, LLC. BG is an employee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Corrona, LLC. JDG is an employee of New York University School of Medicine and Corrona, LLC; has received stock from Corrona, LLC; and has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Celgene, Genentech, Biogen Idec Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutical Products, LP, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, and Pfizer. RL is an employee of UCB Pharma. JS is an employee of UCB Pharma. RS is an employee of UCB Pharma. SJ is an employee of UCB Pharma. JMK is an employee of Corrona, LLC, and has received stock from Corrona, LLC; consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Genentech, GSK, Eli Lilly and Co., Medimmune, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and research grants from AbbVie, Genentech, Eli Lilly and Co., Novartis, and Pfizer. MY is an employee of UCB Pharma.

Publisher’s Note

All the results presented in this manuscript are in aggregate form and no personal identifiable information was used for this study.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Modified Charlson comorbidity index. Table S1. Other AEs of interest. (PDF 246 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Harrold, L.R., Litman, H.J., Saunders, K.C. et al. One-year risk of serious infection in patients treated with certolizumab pegol as compared with other TNF inhibitors in a real-world setting: data from a national U.S. rheumatoid arthritis registry. Arthritis Res Ther 20, 2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1496-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1496-5