Abstract

Psoriatic arthritis is a part of the family of diseases referred to as spondyloarthropathies, a diverse group of chronic inflammatory disorders with common clinical, radiographic, and genetic features. Peripheral arthritis is the most common symptom of psoriatic arthritis and patients also frequently experience involvement of the entheses, spine, skin, and nails. Due to the diverse clinical spectrum of disease severity, tissues affected, and associated comorbidities, the treatment of psoriatic arthritis can be challenging and it is necessary to mitigate risks associated with both the disease and its treatment. These risks include disease-specific, treatment-related, and psychological risks. Disease-specific risks include those associated with disease progression that can limit functional status and be mitigated through early diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Risks also arise from comorbidities that are associated with psoriatic arthritis such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and gastrointestinal inflammation. Patient outcomes can be affected by the treatment strategy employed and the pharmacologic agents administered. Additionally, it is important for physicians to be aware of risks specific to each therapeutic option. The impact of psoriatic arthritis is not limited to the skin and joints and it is common for patients to experience quality-of-life impairment. Patients are also more likely to have depression, anxiety, and alcoholism. This article reviews the many risks associated with psoriatic arthritis and provides guidance on mitigating these risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a member of the spondyloarthropathies (SpA) family of diseases, a diverse group of chronic inflammatory rheumatic disorders with common clinical, radiographic, and genetic features [1, 2]. There are a wide variety of clinical and anatomic characteristics that distinguish PsA from other chronic rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other forms of SpA [3, 4]. The primary regions affected in patients with PsA are the peripheral joints, entheses (connective tissue between tendon or ligament and bone), and axial sites, often in an asymmetrical pattern, in addition to psoriasis of the skin and nails [4, 5]. In addition to the larger joints, the small joints of the fingers, including the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints—which are generally spared by RA—and toes are also typically involved in PsA [5]. Further, up to 43% of patients with PsA experience sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac [SI] joint) in the spinal column [6]. Dactylitis (swelling of an entire digit) is also common in patients with PsA and is a marker of disease progression [7]. Although PsA is commonly associated with the presence of psoriasis, skin disease and joint inflammation do not always present concurrently [2].

The prevalence of PsA in the United States is 0.25% [8]. However, the prevalence of PsA in patients with psoriasis is substantially higher, with approximately 30% of individuals reported to have both conditions [9]. PsA is reportedly more common in women than in men compared with ankylosing spondylitis [5, 10]. Although it is important to recognize that there may be some degree of selection bias in this regard (due to conventional wisdom and teaching that women are unlikely to develop ankylosing spondylitis).

The differentiation of PsA from RA can be aided by certain clinical characteristics. Unlike RA, PsA is not associated with circulating autoantibodies [3, 11]. Patients with PsA are usually seronegative (absence of circulating rheumatoid factor) and a negative test for rheumatoid factor is one component of the ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) [2, 12]. Additionally, PsA and RA typically have distinct patterns of inflammatory joint damage, which can be distinguished through specific clinical and radiological changes. The clinical pathology of PsA typically presents in the distal interphalangeal and axial joints, with an asymmetrical distribution, whereas RA is primarily symmetrically distributed in the metacarpophalangeal and wrist joints [3]. However, PsA may also present as a symmetrical arthropathy or as an oligoarthropathy. The vascular pathology of PsA is distinct from RA and is characterized by a hypervascularized network of elongated, tortuous vessels [3]. Whereas RA primarily results in bone and cartilage resorption, PsA has both bone destruction and formation traits [13]. Both patients with RA and PsA experience erosion that leads to resorption of cortical bone, but additional formation of bony spurs is observed along insertion sites of entheses only in patients with PsA [13].

Like other forms of SpA, susceptibility to PsA is associated with the human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) gene [2]. The strength of the association between HLA-B27 and disease susceptibility varies among different SpA subtypes as well as between ethnic groups and the presence of HLA-B27 in combination with other major histocompatibility complex class alleles may influence the pattern of axial or peripheral disease presentation [14].

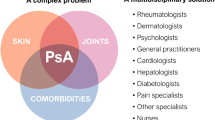

The clinical spectrum of PsA is extremely diverse in both disease severity and tissues affected, and this disorder often occurs in conjunction with several associated comorbidities [4, 15]. The array of symptoms, coupled with the wide range in severity and disease course, presents difficult challenges for treatment [16]. Mitigation of risks associated with the disease itself, its treatment, and associated comorbidities are all important considerations when managing patients with PsA (Table 1). This review will discuss and highlight the many risks associated with PsA, with the aim to help improve awareness of risks among physicians and to provide guidance in mitigating these risks.

Disease-specific risks

Risks associated with disease progression

Early diagnosis and treatment of PsA is important because the disease not only causes functional impairment over time, but also may increase the risk of mortality in affected patients [15]. Unfortunately, early detection methods for PsA remain limited and the disease is often underdiagnosed due to symptoms going unrecognized [15]. Common initial symptoms include arthritis in the upper and lower limbs (Table 2).

For proper treatment of PsA, it is necessary to consider all aspects of the disease, including clinical pathology and psychological issues [15]. Further, worse outcomes in patients with PsA are associated with a delay in diagnosis, disability, and joint damage, whereas male sex and lower burden of inflammation at presentation were predictors of improved patient outcomes [17–19]. The presence of specific HLA alleles can also identify patients likely to sustain joint damage [19].

Maintaining good functional status is the primary aim of pharmacologic treatment in patients with PsA. Although the recommended approaches to the diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up of patients with PsA have changed numerous times over the past decade, the goal of treatment is remission or, alternatively, low disease activity or minimal disease activity (MDA) if remission is not attainable [20, 21]. Loss of physical functioning directly impairs patient quality of life (QoL) and results in increased direct and indirect costs associated with the disease [22]. For example, decreased functional status can prevent patients from performing daily activities of living, such as washing and dressing [23].

Clinicians should be aware of the relevant extra-articular manifestations of PsA and its associated comorbidities, which result in considerable morbidity and mortality [24]. At least 1 extra-articular immune-mediated inflammatory disease is present in 94.7% of patients with PsA and the most common of these are psoriasis (94%), uveitis (1.3%), and inflammatory bowel disease (0.7%) [25]. The extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities associated with PsA can also significantly impact QoL and must be considered in the management of PsA [23].

Risks associated with comorbidities

Patients with PsA have a higher prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular (CV) disease than the general population [24, 26]. This increased risk is due to both a higher prevalence of traditional risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, and also to nonconventional risk factors, for example, those related to chronic systemic inflammation, including higher levels of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [24, 27]. Interestingly, suppression of inflammation in patients with PsA has been linked with improvements in surrogate markers of CV risk, such as increased carotid intima media thickness and endothelial dysfunction [28]. Further, the presence of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, which are also more common in patients with PsA, are associated with increased severity of PsA and increased risk of CV disease [29, 30]. These findings suggest that systemic inflammation may play an important role in driving CV risk in patients with PsA.

Obesity is reported in 35% of patients with PsA and has been suggested as a potential risk factor for developing PsA [31, 32]. Obesity may also impact disease activity and response to therapy, possibly through increased production of inflammatory cytokines [33]. For instance, irrespective of the kind of therapy used, obesity is associated a lower probability of achieving MDA and it is speculated that the chronic pro-inflammatory state, the biomechanical effect of heavy weight on the joints, and the altered pain threshold associated with obesity may be factors responsible preventing achievement of MDA [32].

PsA is associated with diabetes mellitus and the rate of diabetes mellitus is significantly higher in patients with PsA than in those with RA (odds ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–2.28; P = 0.02) [34]. Caution should be used if prescribing glucocorticoids because they are associated with an approximately 30% increase in the risk for developing diabetes mellitus in patients with psoriasis or PsA [35]. Some dermatologists consider psoriasis as a contraindication for use of corticosteroids, due to concerns of converting plaque psoriasis into pustular psoriasis. However, corticosteroids are still often used across various practice settings, including dermatology.

A strong relationship has been noted between gastrointestinal (GI) inflammation and joint inflammation in various forms of SpA [36]. However, the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with PsA is less clearly defined [24]. Of note, there is a significantly increased risk of Crohn’s disease in women with psoriasis (relative risk [RR] 3.86, 95% CI 2.23–6.67) that is further increased in women with both psoriasis and PsA (RR 6.43, 95% CI 2.04–20.32) [37].

Patients with PsA also suffer from sleep disturbances and diminished sleep quality that are associated with generalized pain, anxiety, enthesitis, increased levels of C-reactive protein, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate [38]. The prevalence of depression in patients with PsA is 22.2%, compared with 9.6% in patients with psoriasis alone, and the estimated prevalence in the general population (9%) [39]. Similarly, the prevalence of anxiety among patients with PsA is reported as 36.6%, compared with 24.4% in patients with psoriasis alone [39].

Mitigation of disease-specific risks

Mitigation and evaluation of disease-specific risks is dependent upon prompt and accurate diagnosis. Currently, the primary objectives in clinical rheumatology are early diagnosis and initiation of treatment because diagnostic delays are a significant contributor to poor patient outcomes [4, 15]. Even short delays (6 months) from symptom onset to first visit with a rheumatologist have been observed to contribute to development of peripheral joint erosions and worse long-term physical function [40]. To this end, remission in PsA has been attributed to early diagnosis and treatment.

Disease-related risks should be evaluated through good patient history and use of metrics specific to PsA [41]. These include evaluation of physical function and skin involvement, as well as joint examination (tender joint count, swollen joint count, entheseal assessment). Additionally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of PsA when diagnosing and treating patients who suffer from pre-existing psoriasis. Tracking of metrics over time should be undertaken to detect whether medications are ameliorating disease severity. Imaging may be used for diagnosis and following disease progression over time [41]. In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography have been increasingly used for assessment of PsA and have provided additional information on the pathogenesis of PsA [15].

Treatment with drugs is necessary for patients with PsA and recommended treatment guidelines tailored to individual PsA characteristics are shown in Fig. 1 [16]. Although it is important for patients with PsA to remain active, it is typically not possible to manage disease symptoms through physical therapy alone.

GRAPPA treatment schema for active PsA [16]. Reprinted with permission from: Coates LC et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68(5):1060–1071

Treatment-related risks

Risks associated with treatment strategy

Early recognition and intervention with therapy is key to controlling disease progression in patients with PsA [15]. The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been shown to improve signs and symptoms of PsA [42–46]. Additionally, apremilast (an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor), abatacept (a T cell selective costimulation modulator), ustekinumab (an interleukin- [IL-] 12/23 inhibitor), and secukinumab (an IL-17A inhibitor) have also shown varying degrees of efficacy in the treatment of PsA [47–53]. Approved agents are discussed in more detail in the following section.

Treat-to-target is a therapeutic concept derived from RA and other diseases [54, 55], which has been proposed for all forms of SpA [20, 41, 54, 56]. With this approach, a clear target, such as remission or low disease activity, is identified and the goal is to sustain this response over time, with an understanding of the need to treat flares and keep tight control of disease activity [55]. A universal definition of the target (e.g., remission, prevention of flare of disease) is required for the treat-to-target approach and, in SpA, remission and sustained low disease activity have been suggested as possible targets [20, 55]. Although definitions of remission or MDA in SpA have been proposed, none have been widely accepted or endorsed and given the multifaceted nature of SpA, a composite of outcome measures may be most useful [54, 57].

The Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) trial, an open-label, randomized, controlled study, has recently provided evidence on the benefit of treating-to-target in PsA [58]. This study compared treat-to-target versus standard of care in newly diagnosed patients with PsA receiving methotrexate (MTX), a combination of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), or TNF inhibitors. Results from TICOPA demonstrated that tight control of disease activity using a step-up dosing regimen to achieve MDA (reviewed and adjusted, if necessary, every 4 weeks) significantly improved joint outcomes compared with standard of care (per the treating physician, reviewed every 12 weeks). After 48 weeks, the odds of achieving an American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20% criteria for improvement (ACR20 response) nearly doubled (odds ratio 1.91; 95% CI, 1.03–3.55; P = 0.0392) without any unexpected serious adverse events (AEs) [58].

Risks associated with pharmacologic treatment

The complexities of PsA pathology suggest the need to identify suitable therapies to address the different combinations of clinical manifestations [21]. Traditional treatments for PsA include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, and synthetic DMARDs [59]. NSAIDs are effective for relieving musculoskeletal symptoms due to joint inflammation, but have no efficacy on psoriatic skin lesions and are associated with AEs including renal toxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, and the risk of developing CV events [59]. Traditional DMARD treatment options for PsA include sulfasalazine and MTX [16, 59, 60]. There is debate over the efficacy of MTX and randomized trials have generally been unable to show efficacy [59, 61, 62]. Additionally, MTX is ineffective in treating axial inflammation and there is little evidence to support its use for other symptoms such as enthesitis [59, 62]. However, in the placebo-controlled Methotrexate in Psoriatic Arthritis (MIPA) trial (that showed no benefit with respect to the primary endpoint of PsA response criteria), treatment with MTX resulted in a significant improvement over placebo in both patient and physician global assessments, as well as Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores at 6 months [61, 62]. Nonetheless, the MIPA authors asserted that their findings questioned the classification of MTX as a DMARD in the setting of PsA, with recognition that there are safety concerns associated with MTX therapy [61]. In particular, the use of MTX in obese patients may lead to potential liver damage [63]. Alcohol abuse and the high prevalence of fatty liver in obese patients may contribute to the development of liver damage and the presence of fatty liver can also impede monitoring for liver damage.

Current targeted treatment options approved for PsA include biologics (TNF inhibitors, ustekinumab, and secukinumab) and the small molecule apremilast [3, 59]. These therapies are typically recommended for use after inadequate response to at least one DMARD but early escalation can be considered, especially for patients with poor prognostic factors such as raised inflammatory markers or high active-disease joint counts [16]. For patients who fail a biologic therapy, the GRAPPA guidelines provide a conditional recommendation for switching to a different biologic agent within a drug class or to a drug with a different mode of action [16]. While switching TNF inhibitors can be effective, response rates tend to diminish with successive TNF inhibitor use [64]. There has been investigation of combining TNF inhibitors with a DMARD to prolong biologic persistence but a clear benefit of combination therapy was not observed [65]. There are currently two biologics (secukinumab and ustekinumab) available for treatment of PsA with a different mechanisms of action than TNF inhibition [50, 51, 53]. A concern with all biologic therapies for PsA is an increased risk for infections and patients should be monitored for the development of serious infections that would necessitate discontinuation of treatment until the infection resolves. Reactivation of tuberculosis has been observed with TNF inhibitors and patients must be monitored for active tuberculosis while receiving these agents.

Additionally, response to biologic agents can be limited by immunogenicity and the development of antidrug antibodies [66]. Antidrug antibodies have been observed in 29% of patients receiving adalimumab and 21% of patients receiving infliximab and their presence was significantly correlated with low drug levels and high levels of disease activity [66]. This study also reported that MTX significantly decreased the prevalence of antidrug antibodies, and use of MTX should be considered for patients treated with TNF inhibitors. With secukinumab and ustekinumab, treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies were reported in 0.2% to 0.3% and 9.3%, respectively, of patients from phase 3 trials [49, 52, 53]. In patients receiving ustekinumab and MTX, antidrug antibodies were less common (6.4%) than in those only receiving ustekinumab (12.3%) [52].

Treatment of skin disease associated with PsA can include phototherapy such as ultraviolet B or oral psoralen followed by ultraviolet A (PUVA) [67]. PUVA therapy carries an increased risk of skin cancer compared with other forms of ultraviolet light treatment and patients receiving this treatment should be monitored for skin cancer [67, 68].

Risks associated with poor compliance

Patient compliance to therapy is an underlying concern in the management of PsA. In patients treated with TNF inhibitors, age has been associated with increased compliance and female sex, comorbidity, and poor clinical condition at baseline have been associated with decreased compliance [69]. Poor adherence can reduce therapeutic efficacy and increase medical costs due to the need for more aggressive treatments [69, 70]. In general, there is the potential for reduced compliance if a patient cannot observe their disease directly, although this is less likely in patients with PsA because skin involvement is more common.

Psychosocial risks

The impact of PsA is not limited to the skin and joints and patients often experience substantial impairment in QoL [71]. There is an increased risk of depression and anxiety in patients with PsA, which can complicate treatment [71]. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are associated with low treatment adherence in chronic diseases and can impair the ability of patients to self-manage [72]. Physicians should remain cognizant of depressive behaviors such as alcoholism, nonsocial behavior, drug addiction, and suicide ideation and even though treatment of PsA can improve symptoms of depression and anxiety, it is still important for physicians to identify individuals who would benefit from referral for counseling.

Patients with both PsA and psoriasis experience worse QoL than those with only psoriasis [73]. Additionally, this difference in QoL was not due to differences in other comorbidities between patients with and without joint involvement [73]. Collectively, further efforts should be made by physicians to identify patients with PsA who should be referred for counseling as well as to monitor changes in these psychosocial issues over the course of treatment.

Conclusions

Among patients with PsA, a major emphasis of comprehensive care should be aimed at mitigating risks and improving physical health-related QoL. As outlined above, this may be achieved by early diagnosis, prevention of disease progression, treatment of PsA-associated physical morbidity, mitigation of treatment-related risk, and treatment of associated medical comorbidity. Various agents, including newer biologics, have approved indications for use in the PsA population—providing the clinician and patients with choices of agents based on their specific disease symptoms. Overall, management of patients with PsA is complex and requires the adoption of a more patient-focused multidisciplinary approach.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- AEs:

-

Adverse events

- CASPAR:

-

ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- DIP:

-

Distal interphalangeal

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- GRAPPA:

-

Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MDA:

-

Minimal disease activity

- MIPA:

-

Methotrexate in Psoriatic Arthritis

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PASI:

-

Psoriatic Area and Severity Index

- PsA:

-

Psoriatic arthritis

- PUVA:

-

Psoralen followed by ultraviolet A

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SI:

-

Sacroiliac

- SpA:

-

Spondyloarthropathies

- TICOPA:

-

Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Collantes E, Zarco P, Muñoz E, Juanola X, Mulero J, Fernández-Sueiro JL, et al. Disease pattern of spondyloarthropathies in Spain: description of the first national registry (REGISPONSER)—extended report. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1309–15.

Zochling J, Smith EU. Seronegative spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:747–56.

Veale DJ, Fearon U. What makes psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis so different? RMD Open. 2015;1:e000025.

Haroon M, FitzGerald O. Psoriatic arthritis: complexities, comorbidities and implications for the clinic. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:405–16.

Amherd-Hoekstra A, Näher H, Lorenz HM, Enk AH. Psoriatic arthritis: a review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:332–9.

Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii14–7.

Brockbank JE, Stein M, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: a marker for disease severity? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:188–90.

Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Smith N, Margolis DJ, Nijsten T, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:573.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, Khraishi MM, Thaci D, Behrens F, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:729–35.

Haroon NN, Paterson JM, Li P, Haroon N. Increasing proportion of female patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based study of trends in the incidence and prevalence of AS. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006634.

Sanmarti R, Graell E, Perez ML, Ercilla G, Viñas O, Gómez-Puerta JA, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of antibodies against chimeric fibrin/filaggrin citrullinated synthetic peptides in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R135.

Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665–73.

Schett G, Coates LC, Ash ZR, Finzel S, Conaghan PG. Structural damage in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: traditional views, novel insights gained from TNF blockade, and concepts for the future. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13 Suppl 1:S4.

Londono J, Santos AM, Peña P, Calvo E, Espinosa LR, Reveille JD, et al. Analysis of HLA-B15 and HLA-B27 in spondyloarthritis with peripheral and axial clinical patterns. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009092.

Liu JT, Yeh HM, Liu SY, Chen KT. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Orthop. 2014;5:537–43.

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Soriano ER, Laura Acosta-Felquer M, Armstrong AW, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060–71.

Gladman DD, Hing EN, Schentag CT, Cook RJ. Remission in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1045–8.

Saber TP, Ng CT, Renard G, Lynch BM, Pontifex E, Walsh CA, et al. Remission in psoriatic arthritis: is it possible and how can it be predicted? Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R94.

Eder L, Gladman DD. Predictors for clinical outcome in psoriatic arthritis - what have we learned from cohort studies? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:763–70.

Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M, Emery P, Fitzgerald O, Helliwell P, et al. Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:6–16.

Elyoussfi S, Thomas BJ, Ciurtin C. Tailored treatment options for patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: review of established and new biologic and small molecule therapies. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:603–12.

Zhu TY, Tam LS, Lee VW, Hwang WW, Li TK, Lee KK, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Hong Kong. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1422–5.

Singh JA, Strand V. Spondyloarthritis is associated with poor function and physical health-related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1012–20.

Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Husni ME. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:118–26.

Zarco P, González CM, Rodríguez de la Serna A, Peiró E, Mateo I, Linares L, et al. Extra-articular disease in patients with spondyloarthritis. Baseline characteristics of the spondyloarthritis cohort of the AQUILES study. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:83–9.

Horreau C, Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Barnetche T, Misery L, Cribier B, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27 Suppl 3:12–29.

Zhu TY, Li EK, Tam LS. Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheumatol. 2012;2012:714321.

Jamnitski A, Symmons D, Peters MJ, Sattar N, McInnes I, Nurmohamed MT. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:211–6.

Bostoen J, Van Praet L, Brochez L, Mielants H, Lambert J. A cross-sectional study on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in psoriasis compared to psoriatic arthritis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:507–11.

Haroon M, Gallagher P, Heffernan E, FitzGerald O. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome and of insulin resistance in psoriatic arthritis is associated with the severity of underlying disease. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1357–65.

Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong B, Feng BJ, Goldgar DE, Duffin KC, Krueger GG. Obesity in early adulthood as a risk factor for psoriatic arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:721–6.

Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. Obesity is associated with a lower probability of achieving sustained minimal disease activity state among patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:813–7.

Versini M, Jeandel PY, Rosenthal E, Shoenfeld Y. Obesity in autoimmune diseases: not a passive bystander. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:981–1000.

Labitigan M, Bahče-Altuntas A, Kremer JM, Reed G, Greenberg JD, Jordan N, et al. Higher rates and clustering of abnormal lipids, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in psoriatic arthritis compared with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:600–7.

Solomon DH, Love TJ, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Risk of diabetes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2114–7.

Elewaut D, Matucci-Cerinic M. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and extra-articular manifestations in everyday rheumatology practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:1029–35.

Li WQ, Han JL, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn’s disease in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1200–5.

Gezer O, Batmaz I, Sariyildiz MA, Sula B, Ucmak D, Bozkurt M, et al. Sleep quality in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014.doi:10.1111/756-185X.12505. [Epub ahead of print].

McDonough E, Ayearst R, Eder L, Chandran V, Rosen CF, Thavaneswaran A, et al. Depression and anxiety in psoriatic disease: prevalence and associated factors. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:887–96.

Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1045–50.

Rohekar S, Chan J, Tse SM, Haroon N, Chandran V, Bessette L, et al. 2014 Update of the Canadian Rheumatology Association/spondyloarthritis research consortium of Canada treatment recommendations for the management of spondyloarthritis. Part I: principles of the management of spondyloarthritis in Canada. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:654–64.

Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Siegel EL, Cohen SB, Ory P, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2264–72.

Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, Wollenhaupt J, Khraishi M, Kielar D, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:48–55.

Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1150–7.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3279–89.

Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, Krueger GG, Gladman D, Gomez-Reino J, et al. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor α antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis: twenty-four-week efficacy and safety results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:976–86.

Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, Adebajo AO, Wollenhaupt J, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1020–6.

Mease P, Genovese MC, Gladstein G, Kivitz AJ, Ritchlin C, Tak PP, et al. Abatacept in the treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:939–48.

Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Rahman P, van der Heijde D, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1329–39.

McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, Puig L, Rahman P, Ritchlin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382:780–9.

McInnes IB, Sieper J, Braun J, Emery P, van der Heijde D, Isaacs JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriatic arthritis: a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:349–56.

Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Puig L, Li S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:990–9.

McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Rahman P, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–46.

Miedany YE. Treat to target in spondyloarthritis: the time has come. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2014;10:87–93.

Wendling D. Treating to target in axial spondyloarthritis: defining the target and the arrow. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:691–3.

Schoels MM, Braun J, Dougados M, Emery P, Fitzgerald O, Kavanaugh A, et al. Treating axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis, including psoriatic arthritis, to target: results of a systematic literature search to support an international treat-to-target recommendation in spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:238–42.

Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:48–53.

Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L, Brown S, Navarro-Coy N, O’Dwyer JL, et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA): a UK multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2489–98.

Kang EJ, Kavanaugh A. Psoriatic arthritis: latest treatments and their place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6:194–203.

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux-Viala C, Ash Z, Marzo-Ortega H, van der Heijde D, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:4–12.

Kingsley GH, Kowalczyk A, Taylor H, Ibrahim F, Packham JC, McHugh NJ, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:1368–77.

Mease PJ. Spondyloarthritis: is methotrexate effective in psoriatic arthritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:251–2.

Berends MA, Snoek J, de Jong EM, van de Kerkhof PC, van Oijen MG, van Krieken JH, et al. Liver injury in long-term methotrexate treatment in psoriasis is relatively infrequent. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:805–11.

Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Krogh NS, Andersen MD, Tarp U, Loft AG, et al. Clinical response, drug survival, and predictors thereof among 548 patients with psoriatic arthritis who switched tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1213–23.

Mease PJ, Collier DH, Saunders KC, Li G, Kremer JM, Greenberg JD. Comparative effectiveness of biologic monotherapy versus combination therapy for patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from the Corrona registry. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000181.

Zisapel M, Zisman D, Madar-Balakirski N, Arad U, Padova H, Matz H, et al. Prevalence of TNF-α blocker immunogenicity in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:73–8.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 5. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:114–35.

Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, Gallini A, Aubin F, Le Maitre M, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 3:22–31.

López-González R, León L, Loza E, Redondo M, de Yébenes MJG, Carmona L. Adherence to biologic therapies and associated factors in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:559–69.

Blum MA, Koo D, Doshi JA. Measurement and rates of persistence with and adherence to biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2011;33:901–13.

Lee S, Mendelsohn A, Sarnes E. The burden of psoriatic arthritis: a literature review from a global health systems perspective. P T. 2010;35:680–9.

Betteridge N, Boehncke WH, Bundy C, Gossec L, Gratacós J, Augustin M. Promoting patient-centred care in psoriatic arthritis: a multidisciplinary European perspective on improving the patient experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:576–85.

Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:571–6.

Rojas-Vargas M, Muñoz-Gomariz E, Escudero A, Font P, Zarco P, Almodovar R, et al. First signs and symptoms of spondyloarthritis—data from an inception cohort with a disease course of two years or less (REGISPONSER-Early). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:404–9.

Acknowledgements

Technical assistance with editing and styling of the manuscript for submission was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc. and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Funding

The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions and received no financial support or other form of compensation related to the development of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable. No data sets were generated or analyzed in the preparation of this manuscript. The texts of the published references, as cited, were the sources used.

Authors’ contributions

MB conceived of the concept for this review, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted and reviewed the content of the manuscript. AL conceived of the concept for this review, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted and reviewed the content of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

MB is a consultant/speaker for Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Genentech, Horizon, Iroko, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer, and holds stock in Merck, BMS, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson. AL has no competing interests to declare.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergman, M., Lundholm, A. Mitigation of disease- and treatment-related risks in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 19, 63 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1265-5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1265-5