Abstract

Background

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), who by definition have radiographic sacroiliitis, typically experience symptoms for a decade or more before being diagnosed. Yet, even patients without radiographic sacroiliitis (i.e., nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis [nr-axSpA]) report a significant disease burden. The primary objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence and clinical characteristics of nr-axSpA among patients with inflammatory back pain (IBP) in rheumatology clinics in a number of countries across the world. A secondary objective was to estimate the prevalence of IBP among patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

Methods

Data were collected from 51 rheumatology outpatient clinics in 19 countries in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia. As consecutive patients with CLBP (N = 2517) were seen by physicians at the sites, their clinical histories were evaluated to determine whether they met the new Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria for IBP. For those who did, their available clinical history (e.g., family history, C-reactive protein [CRP] levels) was documented in a case report form to establish whether they met criteria for nr-axSpA, AS, or other IBP. Patients diagnosed with nr-axSpA or AS completed patient-reported outcome measures to assess disease activity and functional limitations.

Results

A total of 2517 patients with CLBP were identified across all sites. Of these, 974 (38.70 %) fulfilled the criteria for IBP. Among IBP patients, 29.10 % met criteria for nr-axSpA, and 53.72 % met criteria for AS. The prevalence of nr-axSpA varied significantly by region (p < 0.05), with the highest prevalence reported in Asia (36.46 %) and the lowest reported in Africa (16.02 %). Patients with nr-axSpA reported mean ± SD Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Scores based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP of 2.62 ± 1.17 and 2.52 ± 1.21, respectively, indicating high levels of disease activity (patients with AS reported corresponding scores of 2.97 ± 1.13 and 2.93 ± 1.18). Similarly, the overall Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index score of 4.03 ± 2.23 for patients with nr-axSpA (4.56 ± 2.17 for patients with AS) suggested suboptimal disease control.

Conclusions

These results suggest that, in the centers that participated in the study, 29 % of patients with IBP met the criteria for nr-axSpA and 39 % of patients with CLBP had IBP. The disease burden in nr-axSpA is substantial and similar to that of AS, with both groups of patients experiencing inadequate disease control. These findings suggest the need for early detection of nr-axSpA and initiation of available treatment options to slow disease progression and improve patient well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a constellation of chronic inflammatory conditions that includes ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis, among others [1]. Collectively, the prevalence of SpA varies between 0.5 % and 2 %, making it approximately as common as rheumatoid arthritis [1]. On the basis of their clinical presentation, patients with SpA can be categorized as having axial SpA, in which the spine is predominantly affected, or peripheral SpA, in which the extremities are predominantly affected [2, 3]. According to the 2009 criteria of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS), axial SpA is further categorized into nonradiographic axial SpA (nr-axSpA) and AS, in which the major distinguishing feature is the presence (for AS) or absence (for nr-axSpA) of radiographic sacroiliitis [2, 3].

Approximately 10 % of patients with nr-axSpA develop AS within 2 years and 60 % develop AS within 10 years [4]. Although patients with nr-axSpA may have inflammation detectable by magnetic resonance imaging [5, 6], early detection of axial SpA poses a major challenge to many physicians [2, 3]. Indeed, patients may experience symptoms for a decade or more before receiving a diagnosis [1]. Patients with axial SpA also report a number of impairments in physical functioning and spinal mobility, experience high rates of disability, and contribute to high societal costs [4]. Timely identification of axial SpA may potentially lead to earlier and more effective intervention to delay disease progression [5].

The majority of axial SpA studies have been conducted in Europe, the United States, and Mexico, with information extremely limited in the emerging countries of Latin America, Africa, Central and Eastern Europe, and Asia. The general population prevalence of axial SpA in Europe has been estimated to be between 0.08 % (France) and 0.49 % (Turkey) [6]. The prevalence is slightly higher in the Americas, with researchers in Mexico and the United States reporting rates of 0.60 % and 0.90–1.40 %, respectively [6, 7].

Many of the studies cited above have been focused on AS or axial SpA, leading to a lack of epidemiological and clinical data specific to nr-axSpA. Indeed, even the proportion of axial SpA patients with nr-axSpA is unknown, as estimates vary considerably, ranging from 23 % to 80 % in a recent review of patients with axial SpA [4]. In part, this is due to different methods of assessment and the fact that these studies were not specifically designed to follow patients with undifferentiated SpA and nr-axSpA [4].

The lack of data on nr-axSpA and AS is even more pronounced in emerging countries in Latin America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. The primary objective of this study was to provide prevalence estimates on the presence of nr-axSpA among patients with inflammatory back pain (IBP) in rheumatology clinics across a number of emerging countries. In this study, we also sought to describe the clinical characteristics associated with both nr-axSpA and AS. A secondary objective was to estimate the prevalence of IBP among patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP), given that IBP represents an increasingly important part of identifying patients with axial SpA [2, 3].

Methods

Study design

A noninterventional, cross-sectional study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of nr-axSpA among patients with IBP in 51 rheumatology outpatient clinics from 19 countries in Latin America (Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru), Europe inclusive of western Asia (Hungary, Israel, Kazakhstan, Poland, Romania, Russia, and Turkey), Africa (Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa), and Asia focused on southern and eastern Asia (Bangladesh, China, India, Malaysia, and Taiwan). Patient recruitment took place from January through December 2014. The protocol and study materials received institutional review board approval at each participating site; the specific sites are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

Consecutive patients with CLBP were seen by participating physicians at the study sites and were evaluated clinically to determine whether they met the criteria for IBP. Patients who met 2009 ASAS criteria for IBP had their clinical histories further evaluated to determine their eligibility for the medical record abstraction portion of this study. The inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, CLBP ≥3 months, and four of five of the following parameters: age of onset <40 years, insidious onset, improvement with exercise, no improvement with rest, and pain at night. The exclusion criteria were noninflammatory back pain, a condition that could mimic IBP (e.g., fibromyalgia), the presence of a neuropathic component, unexplained weight loss of >10 kg within the past 6 months, persistent fever, urinary incontinence or retention, saddle anesthesia, decreased anal sphincter tone or fecal incontinence, bilateral lower extremity weakness or numbness, or progressive neurologic deficit.

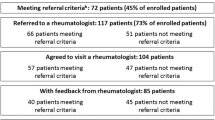

For patients who met the appropriate inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent, a medical record abstraction using a case report form (CRF) was performed to determine whether the patients met the criteria for AS, nr-axSpA, or other forms of IBP (“other IBP” hereafter) based on ASAS criteria for axial SpA and the Modified New York (Modified NY) criteria for AS (Fig. 1). More specifically, patients who did not meet ASAS criteria were classified as having other IBP. Patients who met ASAS criteria for axial SpA but did not meet Modified NY criteria were classified as having nr-axSpA. Patients who met both ASAS criteria for axial SpA and Modified NY criteria were classified as having AS.

Summary of inflammatory back pain (IBP) group classifications. AS ankylosing spondylitis, ASAS Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society, axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, CRP C-reactive protein, HLA-B27 human leukocyte antigen B27, Modified NY criteria Modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis, nr-axSpA nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SpA spondyloarthritis

Patients who were diagnosed with AS or nr-axSpA were provided with a brief survey to evaluate their patient-reported outcomes (PROs). It is important to note that diagnosed refers to the physician’s classification of that patient as indicated in the medical record. It is not known what information was used to make this assessment. The classification of patients based on ASAS criteria for axial SpA and Modified NY criteria for AS, as described above, was an analytical exercise performed by the authors after data collection; it was not conducted in real time as patients were enrolled into the study. As a result, the study depended upon the physician’s classification (referred hereafter as diagnosis to distinguish the methods) in order to identify patients eligible to receive the survey, even if this differed from our methods of classification using the ASAS criteria for axial SpA and the Modified NY criteria for AS. This survey was completed entirely by the patient in the waiting room to avoid any influence from the investigator. At the end of subject recruitment, all completed materials were collected on-site and checked for completion, with the exception of the patient questionnaire, which remained confidential.

Measures

The CRF assessed information on each patient’s demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), general health history (body mass index [BMI], years of experienced CLBP), and disease history (human leukocyte antigen B27 [HLA-B27] test results, C-reactive protein [CRP] results, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] results, family history, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [NSAID] response). The patient survey included the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS; both ESR and CRP versions), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI).

Statistical analysis

The analysis of the primary objectives (prevalence and clinical characteristics of nr-axSpA) was focused on patients with IBP who met the inclusion or exclusion criteria described above. The analysis of the secondary objective (prevalence of IBP among patients with CLBP) was focused on all patients with CLBP. Frequencies, percentages, and 95 % CIs were reported for binary and/or categorical variables. Counts, means, and SDs were reported for continuous variables. Statistical differences across geographical regions were analyzed using chi-square tests and one-way analysis of variance for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Results

Prevalence of nr-axSpA overall, by region, and by sex

A total of 2517 patients with CLBP were identified across all sites (Fig. 2). Of these, 974 (38.70 %) fulfilled the criteria for IBP and were advanced to the CRF portion of the study for assessment of IBP group status (i.e., nr-axSpA, AS, or other IBP). Overall, 29.10 % (95 % CI 26.15–32.05 %) of patients with IBP met the criteria for nr-axSpA (Table 1). The prevalence of AS among patients with IBP was 53.72 % (95 % CI 50.48–56.96 %). The prevalence of nr-axSpA varied significantly by region (p < 0.05), with the highest prevalence reported in Asia (36.46 %, 95 % CI 31.64–41.28 %) and the lowest reported in Africa (16.02 %, 95 % CI 11.00–21.04 %). The prevalence of nr-axSpA was similar among males (28.74 %, 95 % CI 25.07–32.41 %) and females (29.75 %, 95 % CI 24.77–34.74 %) with IBP.

Study flowchart. AS ankylosing spondylitis, ASAS Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society, CLBP chronic low back pain, CRF case report form, IBP inflammatory back pain, Modified NY criteria Modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis, nr-axSpA nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, SpA spondyloarthritis

Demographic characteristics of patients with nr-axSpA

Patients with nr-axSpA had a mean age of 34.75 years (SD 10.03); 36.47 % were female, and 55.64 % were white (Table 2). These figures contrasted with patients with AS, who had a mean age of 39.03 years (SD 11.38); 28.72 % were female, and 68.23 % were white. Minimal regional differences were observed with respect to the demographic characteristics of patients with nr-axSpA (Table 3). Patients with nr-axSpA were oldest in Africa (36.67 years) and youngest in Asia (33.24 years) (p < 0.05); however, no differences in sex, BMI, years since CLBP presentation, or age of IBP onset were observed across regions.

Clinical characteristics of patients with nr-axSpA

Patients with nr-axSpA experienced CLBP for 6.32 ± 7.61 years (compared with 10.91 years for patients with AS) (Table 2). HLA-B27 test results were available for 71.05 % of those with nr-axSpA, and 82.78 % of them had a positive test result (Table 4). Proportions of 68.14 % and 37.30 % of patients with nr-axSpA had elevated CRP and ESR values, respectively. For context, proportions of 77.20 % and 48.92 % of patients with AS had elevated CRP and ESR values, respectively.

Several clinical characteristics varied across regions among those with nr-axSpA (Table 5). Patients in Europe were the most likely to have a positive HLA-B27 test result (84.85 %), and patients in Asia were the least likely (62.24 %) (p < 0.05). Patients in Asia were the most likely to have an elevated ESR value (48.89 %), and patients in Europe were the least likely (20.48 %) (p < 0.05). No differences in family history or NSAID response were observed.

Delay from IBP and CLBP to nr-axSpA or AS diagnosis

For patients who received a diagnosis of nr-axSpA, there was a mean delay of 5.21 ± 7.69 years between the presentation of IBP and diagnosis (Table 4). There was a mean delay of 6.48 ± 8.53 years between the presentation of IBP and diagnosis for patients with AS.

Patient-reported outcomes in nr-axSpA and AS

The mean disease activity levels for patients with nr-axSpA were 2.62 ± 1.17 and 2.52 ± 1.21 for the ESR and CRP versions of the ASDAS, respectively, suggesting a high level of disease activity (i.e., ≥2.1) (Table 6). The mean overall BASDAI score was 4.03 ± 2.32 for patients with nr-axSpA, indicating a suboptimal level of disease control. Finally, BASFI score (3.20 ± 2.47) and BASMI scores (11-point version 2.41 ± 1.54, 3-point version 1.62 ± 1.51, linear function version 3.71 ± 2.77) indicated a significant burden for patients with nr-axSpA and were relatively comparable to BASFI score (4.09 ± 2.59) and BASMI scores (11-point version 4.09 ± 2.06, 3-point version 3.40 ± 2.25, linear function version 4.77 ± 2.38) for patients with AS. No differences in PRO measures were observed across regions, with the exception of the 3-point BASMI version (Africa = 2.59 ± 1.52, Europe = 1.46 ± 1.53, Asia = 1.30 ± 1.36; p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, 39 % of patients referred to rheumatology clinics with CLBP met the ASAS criteria for IBP. Further, 29 % of patients with IBP met the criteria for nr-axSpA. The proportion of axial SpA patients with nr-axSpA was within the range (23–80 %) reported in the literature [4, 8], though on the lower end of prior estimates.

Our data suggest a higher percentage of males among patients with nr-axSpA (64 %) relative to the percentages in other published noninterventional studies (34–50 %) [9, 10] and most clinical trials (48–64 %) [11–16]. There were a number of methodological differences across these studies (e.g., inclusion and exclusion criteria, country), but it is unclear which of these factors would help to explain the differences in results. Further research is necessary.

We found that patients with nr-axSpA were the youngest, and they experienced CLBP for the shortest duration at slightly over 6 years compared with nearly 11 years for patients with AS. Although no age differences were found in past literature reviews between patients with nr-axSpA and those with AS [4, 8], several prior studies have found a longer symptom duration for patients with AS [4–8, 10, 17, 18]. This is to be expected, given that nr-axSpA and AS likely represent a progression in the spectrum of the same disease.

Among patients who had been diagnosed with nr-axSpA, there was a delay of approximately 5 years between presentation of IBP and diagnosis. This finding was consistent with the study by Poddubnyy and colleagues, who which also found a gap of slightly more than 5 years between back pain and the assessment of nr-axSpA [17]. However, it should be noted that many patients who met the criteria for nr-axSpA were not diagnosed even after this period of several years, reinforcing the importance of increasing the awareness of, and adherence to, ASAS classification criteria for timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Among those with HLA-B27 test results, 83 % of the patients with nr-axSpA had positive results. This finding is consistent with what was summarized by Boonen et al. [4] and reported directly in two recent noninterventional studies (73 % in a study by Poddubnyy and colleagues [11] and 86 % in a study by Kiltz and colleagues [18]. Over two-thirds (68 %) of patients with nr-axSpA had elevated CRP values (≥3.5 mg/L), which was nearly as high as the percentage of patients with AS who had elevated CRP values (77 %).

Data derived from the patient surveys demonstrated a high level of disease activity and a suboptimal level of disease control, as assessed using the ASDAS and BASDAI, respectively, for patients with nr-axSpA. It is important to note that even patients with nr-axSpA [19], who are in an earlier phase in the course of axial SpA, exhibited a significant burden that was comparable to that of patients with AS. BASDAI scores in our study were lower than those reported in a review of clinical trial results of biologic treatments [8], suggesting a less severe patient-reported burden in this real-world patient population. The levels of functional impairment (BASFI) and limitations (BASMI) were comparable to those reported for clinical trial populations [4]. Given the early age of onset for nr-axSpA, these impairment data suggest that patients can experience a substantial level of burden for many years. This further illustrates the importance of identifying patients early in order to slow disease progression.

Limitations

Limitations of this epidemiological study include the use of a single assessment with a questionnaire and CRF that may not adequately capture a comprehensive medical history for a particular patient. It is also important to mention that this was an observational study, so not all patients had complete information available. This could have affected the classification of patients and therefore the prevalence estimates. For example, because a positive HLA-B27 test is one way to classify a patient as having nr-axSpA instead of other IBP, missing HLA-B27 data would underestimate the number of nr-axSpA patients relative to other IBP patients. Another limitation was the lack of available information on the other IBP group. Although this group also had poor outcomes based on the PRO data, the explanation for this finding is unclear without knowing more about the composition of the other IBP group. Patient surveys were administered only to patients who were diagnosed with AS and nr-axSpA, so patients who were not diagnosed with either condition, even if they met the appropriate classification criteria, did not provide PRO data. The external validity of the study is dependent on the extent to which patients at the selected rheumatology practices are representative of all IBP patients in these countries. Because these sites were selected for being major centers for the treatment of SpA, it is possible the patients who are managed by these sites are fundamentally different (e.g., more severe disease).

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that approximately one-third of patients with IBP meet ASAS criteria for nr-axSpA. Patients with nr-axSpA, as compared with patients with AS, tend to be younger and experience symptoms for a shorter time before diagnosis. The PRO data suggest that the overall disease burden in nr-axSpA is substantial and similar to that in AS, with both groups of patients experiencing inadequate disease control. These findings show the continued need for early diagnosis of nr-axSpA across Latin America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. These findings also emphasize the importance of early initiation of available treatment options to slow disease progression and improve patient well-being in these patients’ most productive years of life.

Abbreviations

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BMI, body mass index; CLBP, chronic low back pain; CRF, case report form; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen B27; IBP, inflammatory back pain; Modified NY criteria, Modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis; nr-axSpA, nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SpA, spondyloarthritis95 % CI

References

Reveille JD. Spondylarthritis (Spondylarthropathy). 2012. http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Spondyloarthritis. Accessed 2 Jun 2015.

Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:770–6.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83.

Boonen A, Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Bukowski JF, Valluri S, et al. The burden of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:556–62.

Huerta-Sil G, Casasola-Vargas JC, Londoño JD, Rivas-Ruíz R, Chávez J, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. Low grade radiographic sacroiliitis as prognostic factor in patients with undifferentiated spondyloarthritis fulfilling diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis throughout follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:642–6.

Stolwijk C, Boonen A, van Tubergen A, Reveille JD. Epidemiology of spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38:441–76.

Peláez-Ballestas I, Navarro-Zarza JE, Julian B, Lopez A, Flores-Camacho R, Casasola-Vargas JC, et al. A community-based study on the prevalence of spondyloarthritis and inflammatory back pain in Mexicans. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:57–61.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D. Review: Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: new definition of an old disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:543–51.

Dougados M, d’Agostino MA, Benessiano J, Berenbaum F, Breban M, Claudepierre P, et al. The DESIR cohort: a 10-year follow-up of early inflammatory back pain in France: study design and baseline characteristics of the 708 recruited patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:598–603.

Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Listing J, Märker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, et al. Rates and predictors of radiographic sacroiliitis progression over 2 years in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1369–74.

Althoff CE, Sieper J, Song IH, Haibel H, Weiß A, Diekhoff T, et al. Active inflammation and structural change in early active axial spondyloarthritis as detected by whole-body MRI. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:967–73.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Mease PJ, Maksymowych WP, Brown MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomized placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:815–22.

van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:582–91.

Ciurea A, Scherer A, Exer P, Bernhard J, Dudler J, Beyeler B, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibition in radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results from a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3096–106.

Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Braun J, Maksymowych WP, Citera G, et al. Symptomatic efficacy of etanercept and its effects on objective signs of inflammation in early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2091–102.

Landewé R, Braun J, Deodhar A, Dougados M, Maksymowych WP, Mease PJ, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:39–47.

Poddubnyy D, Brandt H, Vahldiek J, Spiller I, Song IH, Rudwaleit M, et al. The frequency of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in relation to symptom duration in patients referred because of chronic back pain: results from the Berlin early spondyloarthritis clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1998–2001.

Kiltz U, Baraliakos X, Karakostas P, Igelmann M, Kalthoff L, Klink C, et al. Do patients with non-radiographic axial spondylarthritis differ from patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1415–22.

Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, Kvien TK, Braun J, Baker D, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off levels for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the various principal investigators at each site who assisted with the data collection: Drs. Bao, Wang, and Wu (China); Dr. Tsai (Taiwan); Drs. Hussein and Lay (Malaysia); Drs. Islam and Rahman (Bangladesh); Drs. Pulukool, Rajshekhar, Sarkar, and Mouli (India); Drs. Itzhak and Levi (Israel); Drs. Kenar, Ozbek, and Karabulut (Turkey); Drs. Ancuta and Opris (Romania); Drs. Elonakov, Kamalova, Lapshina, Dubinina, and Savinkova (Russia); Drs. Świerkot, Chlebicki, Klama, Krezelok, and Zielinski (Poland); Drs. Széntó, Geher, Keszthelyi, Nagy, and Varga (Hungary); Dr. Tleukulov (Kazakhstan); Drs. Casasola, Flores, Ureña, Fajardo, Martinez (Mexico); Drs. Coto and Mendez (Costa Rica); Dr. Parra (Colombia); Dr. Rojo (Peru); Drs. Djoudi, Ladjouze, Dahou, Benzaoui, and Boudersa (Algeria); Drs. Najia, Toufik, Imane, and Radouane (Morocco); and Drs. Reuter and Plooy (South Africa).

The authors also acknowledge the various institutional review boards and ethics committees of the participating institutions: Shanghai Changhai Hospital Ethics Committee (China), Chung Shan Medical Hospital (Taiwan), Kaohsiung Medical University (Taiwan), Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital (Taiwan), Medical Research & Ethics Committee (Malaysia), Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (Bangladesh), Christian Medical College (India), Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences (India), Institutional Ethics Committee of Human Research at Medical College (India), KIMS Foundation and Research Center (India), Bnai Zion Medical Center (Israel), Meir Medical Center (Israel), Dokuz Eylul University (Turkey), Warsaw University of Medicine (Poland), University of Szeged Albert Szent-Gyorgyi Clinical Center (Hungary), Creimed (Colombia), Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of San Martin de Porres (Peru), Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research (Central Ethics Committee of Morocco), National Commission for Personal Data Protection (Central Ethics Committee of Morocco), Medicines Control Council (Central Ethics Committee of South Africa), and Human Research Ethics Committee of Wits Donald Gordon Medical Hospital (South Africa).

The authors also acknowledge Valérie Auclair, PhD, Hélène Kuyas, Xavier Guillaume, MS, MBA, and Geneviève Bonnelye, MS, for their contributions to the study design and data collection, as well as Marco DiBonaventura, PhD, who oversaw the statistical analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. Dr. Auclair, Ms. Kuyas, Mr. Guillaume, Ms. Bonnelye, and Dr. DiBonaventura were all full-time employees of Kantar Health at the time of the study, which received funding from Pfizer. Medical writing support was provided by Marco DiBonaventura, PhD, at Kantar Health and was funded by Pfizer.

Finally, the authors acknowledge the participation of all the patients included in the study.

Authors’ contributions

RBV, JCCW, MUR, NA, SAH, MH, EM, ES, LJL, KS, SK, CH, RP, QS, and BV participated in the study design. MUR, EM, BV, CH, and QS participated in the study coordination and data collection. BV, CH, RP, and QS led the interpretation of the study results with assistance from the remaining authors. All authors helped to draft the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

RBV, JCCW, NA, SAH, and MH were paid to participate as site investigators for the study. This study was sponsored by Pfizer. MUR, EM, ES, LJL, SK, CH, RP, QS, and BV were all full-time employees of Pfizer at the time of this study. The authors declare that they have no nonfinancial competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Burgos-Vargas, R., Wei, J.CC., Rahman, M.U. et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis among patients with inflammatory back pain in rheumatology practices: a multinational, multicenter study. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 132 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1027-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1027-9