Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to directly compare the safety of tocilizumab (TCZ) and TNF inhibitors (TNFIs) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in clinical practice.

Methods

This prospective cohort study included RA patients starting TCZ [TCZ group, n = 302, 224.68 patient-years (PY)] or TNFIs [TNFI group, n = 304, 231.01 PY] from 2008 to 2011 in the registry of Japanese RA patients on biologics for long-term safety registry. We assessed types and incidence rates (IRs) of serious adverse events (SAEs) and serious infections (SIs) during the first year of treatment. Risks of the biologics for SAEs or SIs were calculated using the Cox regression hazard analysis.

Results

Patients in the TCZ group had longer disease duration (P <0.001), higher disease activity (P = 0.019) and more frequently used concomitant corticosteroids (P <0.001) than those in the TNFI group. The crude IR (/100 PY) of SIs [TCZ 10.68 vs. TNFI 3.03; IR ratio (95% confidence interval [CI]), 3.53 (1.52 to 8.18)], but not SAEs [21.36 vs. 14.72; 1.45 (0.94 to 2.25)], was significantly higher in the TCZ group compared with the TNFI group. However, after adjusting for covariates using the Cox regression hazard analysis, treatment with TCZ was not associated with higher risk for SAEs [hazard ratio (HR) 1.28, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.19] or SIs (HR 2.23, 95% CI 0.93 to 5.37).

Conclusions

The adjusted risks for SAEs and SIs were not significantly different between TCZ and TNFIs, indicating an influence of clinical characteristics of the patients on the safety profile of the biologics in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tocilizumab (TCZ), which is a humanized antibody against the interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor [1], inhibits signaling mediated by IL-6 [2] and was first approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Japan in 2008. The superior efficacy of TCZ compared to a control drug or placebo in RA patients has been demonstrated by a series of clinical trials [3-12]. In clinical practice, TCZ showed excellent effectiveness in patients with established RA [13]. Safety profiles of TCZ in patients with RA were clarified by the Japanese post-marketing surveillance (PMS) program [14] and a meta-analysis [15]. In the PMS of TCZ, the most frequent category of serious adverse events (SAEs) was infection and the most common infection was pneumonia. The incidence rate (IR) of serious infections (SIs) per 100 patient-years (PY) was 9.1, with older age, longer disease duration, respiratory diseases, and prednisolone dose ≥5 mg/day at baseline identified as significant risk factors for development of SIs during the first six months of treatment with TCZ [14]. The favorable benefit-risk balance of TCZ has led to the worldwide use of this biologic for treating RA [16].

In 2013, the European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of RA were updated [17]. They now express no preference for the use of a specific biological agent; this indicates that TCZ, as well as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFIs) and abatacept, can be first line biologics. Therefore, for the clinical selection of biologics, it is necessary to compare the efficacy and safety of TCZ with those of other biologics. Systematic reviews [18,19] and meta-analyses [20] indirectly comparing efficacy of TCZ with other biologics showed that TCZ had similar response rates in patients with RA. Results from a clinical trial or study comparing TCZ with another biologic have been reported. Gabay et al. demonstrated that TCZ monotherapy was superior to adalimumab monotherapy in RA patients who are intolerant to methotrexate [21]. A Danish registry reported the comparison of effectiveness between TCZ and abatacept (ABA) [22] and found that declines in disease activity during 48 weeks were similar between the drugs.

There are few data comparing the safety of TCZ with other biologics. A meta-analysis found no significant difference in the risk of SIs between TCZ and other biologics [23]. Using a Japanese single institution registry with a relatively small number of patients, Yoshida et al. reported the safety profiles of TCZ and TNFIs; IRs of SAE were 15.9/100 PY in the TCZ group and 13.9/100PY in the TNFI group [24]. However, to date, no detailed comparison of SAEs between TCZ and TNFIs, particularly the types and incidence of SIs, has been reported. Additional direct observational studies are needed to clarify the risk of use of TCZ versus TNFIs for the development of SAEs and SIs in clinical practice.

In this study, we utilized the database of the registry of Japanese RA patients on biologics for long-term safety (REAL), a prospective, multi-center cohort with a large number of patients, and herein report IRs for each category of SAEs for TCZ with hazard ratios (HRs) for SAEs and SIs from the use of TCZ compared to the use of TNFIs.

Methods

Database

The REAL is a prospective cohort established to investigate the long-term safety of biologics in RA patients. Details of the REAL have been previously described [25]. In brief, 27 institutions participate in the REAL, including 16 university hospitals and 11 referring hospitals. The criteria for enrollment in the REAL include patients meeting the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA [26], written informed consent, and starting or switching treatment with biologics or starting, adding or switching non-biologics at the time of enrollment in the study. Enrollment in the REAL database was started in June 2005 and closed in January 2012. Data were retrieved from the REAL database on 5 March 2012 for this study. This study was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration (revised in 2008). The REAL study was approved by the ethics committees of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital and all other participating institutions. All ethical bodies that approved this study are shown in the Acknowledgements section.

Data collection

Recorded baseline data for each patient includes demography, disease activity, physical disability, comorbidities, treatments, and laboratory data at the beginning of the observation period. A follow-up form was submitted every six months to the REAL Data Center at the Department of Pharmacovigilance of Tokyo Medical and Dental University by site investigators to report the occurrence of SAEs, current RA disease activity, treatments, and clinical laboratory data [25]. Steinbrocker’s classification [27] was used as the baseline measurement for the physical disability of each patient instead of the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index [28]. The investigators in each hospital confirmed the accuracy of their data submitted to the REAL Data Center. The center examined all data sent by site investigators and made inquiries if needed to verify accuracy of the data.

Patients

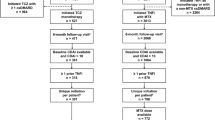

A flow chart of patients enrolled in this study from the REAL is shown in Figure 1. By March 2012, 1,945 patients with RA were registered in the REAL. Of 1,236 patients who started infliximab (IFX), etanercept (ETN), adalimumab (ADA) or TCZ at the time of enrollment or after enrollment in the REAL, we identified 302 patients who started TCZ (TCZ group). Patients who used both TCZ and TNFIs at different periods were assigned to the TCZ group. We then excluded 630 patients who had started any of the TNFIs before 2008 because TCZ was approved for RA in Japan in 2008, and identified 304 patients who started only TNFIs between 2008 and 2011 (TNFI group). The first TNFI of each patient in the TNFI group was IFX for 117 patients, ETN for 80, and ADA for 107. No patients started abatacept, golimumab, or certolizumab pegol in the REAL during the time our data were compiled for this study.

Follow-up

For patients in the TCZ group, the start date for the observation period was the date TCZ was first administered. For patients in the TNFI group, the start of the observation period was the date of the first administration of TNFI from 2008 to 2011. Observation was ended at either 1.0 year after the start of the observation period, or on the date of death of a patient, loss to follow up, enrollment in clinical trials, when therapy with a biologic of interest was discontinued for more than 90 days, or on 5 March 2012, whichever came first. The period following switching to another biologic was excluded from this study. The date of the last administration of each biologic was retrieved from medical records and reported by the site investigators.

Definition of serious adverse events

Our definition of a SAE, including SIs, was based on the report by the International Conference on Harmonization [29]. In addition, bacterial infections that required intravenous administration of antibiotics and opportunistic infections were regarded as SAEs [30,31]. SAEs were classified using the System Organ Class (SOC) of the medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA version 16.0).

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables were used for comparisons among groups. The IR per 100 PY and incidence rate ratios (IRR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Kaplan-Meier methods and log-rank tests were used to compare drug retention rates between the groups. The Cox regression hazard model with the forced entry method was used to calculate HRs of use of TCZ versus TNFIs for SAEs and SIs. As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the same analysis in patients treated with methotrexate (MTX) at baseline, considering substantial differences in clinical characteristics between MTX users and non-users. These statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All P values were two-tailed and P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical baseline characteristics of patients

Baseline data for the patients are shown in Table 1. Compared to the TNFI group, the TCZ group had longer disease duration (P <0.001), higher disease activity (P = 0.019), more advanced disease stage (P <0.001), and poorer physical function (P = 0.005). Age did not differ significantly between the groups. A significantly higher rate of the patients in the TCZ group had received three or more non-biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs before starting the biologic (P = 0.034), was biologic non-naive (P <0.001), and was treated with oral corticosteroids (P <0.001). The proportion of patients treated with MTX in the TCZ group was significantly (P < 0.001) lower than in the TNFI group (n = 160 (53.0%) versus n = 260 (85.5%)). We also compared characteristics of MTX users at baseline. Patients in the TCZ group had significantly longer disease duration (P = 0.003), more advanced stage (P = 0.005) and poorer physical function (P = 0.042) than those in the TNFI group (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Retention rates for TCZ and TNFIs

The median (interquartile (IQR)) treatment period was 1.00 (0.50 to 1.00) year for the TCZ group and 1.00 (0.51 to 1.00) year for the TNFI group. The number of patients who discontinued biologics for any reason during the observation period was 81 (26.8%) in the TCZ group and 62 (20.4%) in the TNFI group, not a significant difference (P = 0.062 by chi-square). The development of AEs was the most frequent reason for discontinuation in both the TCZ group (n = 41, 50.6%) and the TNFI group (n = 24, 38.7%). There was no significant difference in the retention rates of the biologics for one year between the two groups (71.0% in the TCZ group, 76.1% in the TNFI group, P = 0.082 by Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test) (Figure 2).

Types and occurrence of SAEs

The IRs for SAEs are summarized in Table 2. Among the 606 patients, 82 SAEs were reported during the observation period; 48 in the TCZ group and 34 in the TNFI group. The crude IRR, comparing the TCZ group with the TNFI group for SAEs, was 1.45 (95% CI, 0.94 to 2.25) and for SIs was 3.53 (95% CI, 1.52 to 8.18). There were no significant differences in the IR of SAEs among the three TNFIs (data not shown). For patients using MTX at baseline, the IR of SAEs in the TCZ group was not significantly higher than that in the TNFI group (IRR 1.48 95% CI, 0.85 to 2.61), whereas, the IR of SIs was significantly higher in the TCZ group compared to the TNFI group (IRR 2.88 95% CI, 1.13 to 7.32). The IR of SIs in the TCZ group was significantly higher than that in the TNFI group in patients with previous biologics exposure (4.4 (1.7 to 11.6)), but not for SAEs (1.6 (0.8 to 3.0)).

In the TCZ group, 53% of patients had received MTX at baseline; there were no significant differences in the unadjusted IR of SAEs and SIs between MTX users and non-users (data not shown). In the TCZ group, 70% of the patients had previously used biologics; these patients had safety profiles similar to the biologics-naïve patients (data not shown).

In the TCZ group, there were 24 SIs including five cases of opportunistic infections (herpes zoster (two); Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) (one); pulmonary aspergillosis (one); and esophageal candidiasis (one)) and 19 non-opportunistic infections. In the TNFI group, of seven cases with SIs, three were opportunistic infections (herpes zoster (one); PCP (one); and pulmonary cryptococcosis (one)), and four non-opportunistic infections. The respiratory system was the most frequent site of infection in both groups (TCZ (seven) and TNFI (three)), followed in the TCZ group by five in bone and joints and four in skin and subcutaneous tissue. There were no significant differences in the IR for pulmonary infection (IRR 2.40 95% CI, 0.62 to 9.28), but the IR for non-pulmonary infections was significantly higher in the TCZ group compared to the TNFI group (IRR 4.37 95% CI, 1.47 to 13.0). One perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract developed in the TCZ group. No anaphylactic reactions were reported in either group.

Evaluation of risk of TCZ for development of SAEs compared to TNFI

We compared patients who had and had not experienced SAEs using a univariate analysis and selected variables for the multivariate Cox regression hazard analysis to evaluate the risk of the use of TCZ for the development of a SAE. After adjusting for age, gender, disease activity score including 28-joint count C-reactive protein (3), comorbidity, use of oral corticosteroids (prednisolone-equivalent dose) ≥5 mg/day, and Steinbrocker’s class, the hazard ratio (HR) of the use of TCZ compared to the use of TNFI for developing SAEs was 1.28 (95% CI, 0.75 to 2.19, P = 0.370), not significantly elevated (Table 3). Significant risk factors influencing the development of SAEs were age by decade (HR 1.47, 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.88, P = 0.002), the presence of a comorbidity (HR 1.86, 95% CI, 1.07 to 3.24, P = 0.029), and the use of oral corticosteroids (prednisolone-equivalent dose) ≥5 mg/day (HR 1.72, 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.93, P = 0.047) (Table 3). We evaluated the risk of use of TCZ for development of SAEs in patients given MTX at baseline as a sensitivity analysis, and found the HR of use of TCZ was 1.21 (0.55 to 2.65, P = 0.632) compared to the use of TNFI (Table 3).

Evaluation of risk of TCZ for development of SIs compared to TNFIs

We next investigated the risk of use of TCZ compared to the use of TNFI for development of SIs. After comparing patients who had and had not experienced SIs using a univariate analysis, we selected adjusting factors for the multivariate analysis. The HRs for using TCZ compared with TNFI were 2.23 (95% CI, 0.93 to 5.37; P = 0.074) in all the patients and 1.93 (95% CI, 0.72 to 5.17; P = 0.190) in patients treated with MTX at baseline (Table 4). The use of oral corticosteroids (prednisolone-equivalent dose) ≥5 mg/day was a significant risk factor influencing the development of SIs (HR 2.26, 95% CI, 1.02 to 5.01, P = 0.046).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a direct comparison of the safety of TCZ with TNFIs in clinical practice, using a prospective, multi-center cohort with the largest possible number of patients. We demonstrated that the unadjusted IR of SAEs was not significantly higher in the TCZ group compared with the TNFI group, whereas the unadjusted IR of SIs of the TCZ group was 3.5-fold higher than the TNFI group. However, after adjusting for covariates, the use of TCZ compared to the use of TNFIs was not significantly associated with the development of SAEs or SIs.

Some studies have investigated the safety of TCZ in RA patients [4,13,15,32-35]. It has been reported that the IR of SAEs was 20 to 30/100PY and that the most frequent SAE was infection (5 to 9/100PY) [4,14,15,36]. In the present study, the IRs of SAEs (21.36/100PY) and SIs (10.68/100PY) were similar to those of previous reports. The most frequently reported category of SAE in our study was infection and the incidence rate of non-pulmonary infection in the TCZ group was conspicuously higher compared to the TNFI group (7.57/100PY versus 1.73/100PY). Among non-pulmonary infections, skin and bone and joints were common sites in the TCZ group. Previous studies also reported that skin infections, as well as pulmonary infections, were frequently observed in patients treated with TCZ [4,15,24,33,37,38]. Although the reasons for the high incidence rates of these types of infections in patients given TCZ have not been explained, special attention should be paid, not only to pulmonary infections, but also to skin infections in TCZ users.

We found no increased risk for the use of TCZ compared to the use of TNFIs for the development of SIs after adjusting for covariates at baseline. It is notable that the unadjusted IR of SIs in the TCZ group (10.7 (7.02 to 15.6)) was significantly increased compared to the TNFI group (3.53 95%CI, 1.52 to 8.18); this can be explained by several factors. The multivariate analysis indicated that the differences in clinical characteristics of the patients between the two groups influenced the difference in IRs of SIs (Table 4). The use of oral corticosteroids (prednisolone-equivalent dose) ≥5 mg/day was a significant risk factor for SIs in our study. Previous studies have reported that use of oral corticosteroids significantly increased the risk of SIs in patients undergoing treatment with biologics [29,39,40]. Patients in the TCZ group of our study used concomitant corticosteroids more frequently. It has been shown that the presence of comorbidities increased the risk of SIs in RA patients [41]. Although the HR of comorbidities was 2.20 in our study, it did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.067). Relatively more patients in the TCZ group than in the TNFI group had at least one comorbidity (34.1% for the TCZ group, 27.3% for the TNFI group, P = 0.069). These data indicate that patients in the TCZ group may be more predisposed to infections than those in the TNFI group.

The low IR of SIs in the TNFI group apparently contributed to the increased IRR of SIs. The IR of SIs in the TNFI group in our study (3.03/100 PY) was lower than in previous studies (5 to 6/100PY) [25,29,42,43], resulting in an increased IRR when comparing TCZ and TNFIs. We previously reported a significant decrease over time of the risk for SIs with TNFI treatment, possibly explained by evidence-based risk management of RA patients given TNFIs [44]. In the present study, patients in the TNFI group started TNFIs in or after 2008, five years after the approval of IFX for RA in Japan. Information about risk of SIs in patients given TNFIs from observational studies has been extensively shared among Japanese rheumatologists, leading to improved risk management and, in consequence, lowered IRs for SIs in the TNFI group [44]. To accurately compare the outcome between a new drug and an existing one, differences in the calendar year of drug approval should be considered. Therefore, in our study, we compared the use of two biologics, TCZ and TNFIs, in clinical practice during the same time period.

There are potential limitations of this study. First, we have to mention the possibility of selection bias. The patients in this study were enrolled from university hospitals or referral hospitals that are dedicated to the treatments of RA, which may indicate unidentified selection bias. However, because almost all patients who were registered from the participating hospitals to the all-cases post-marketing surveillance programs for each biological DMARD were enrolled in the REAL, selection bias was substantially low. Second, although there is concern about information bias, such as recall bias and reporting bias, in epidemiological studies in general, we collected patient data using the same case report form prospectively, which should overcome the misclassification and underestimation of SAEs derived from these types of bias. Third, clinical practice is always accompanied by the indication bias occurring when a drug is preferentially prescribed to patients with different baseline characteristics. In this study, it was notable that the difference in the percentage of patients who were given MTX at baseline between the two groups was significant, which would have affected the results of our study. To address this possibility, we estimated the risk of SAEs and SIs in patients with concomitant MTX in addition to the whole study population, and found them to be similar. Fourth, we did not investigate the comparison of effectiveness between the two groups due to incomplete data about disease activity in some patients.

Conclusions

The adjusted risks for SAEs and SIs between TCZ and TNFI were not significantly different in clinical practice, although significantly higher IRs for SIs were observed in the TCZ group, possibly attributable to more infection susceptible clinical characteristics of the patients in the TCZ group.

Abbreviations

- ABA:

-

abatacept

- ADA:

-

adalimumab

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAS28:

-

disease activity score including 28-joint count

- ETN:

-

etanercept

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- IFX:

-

infliximab

- IL:

-

interleukin

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- IR:

-

incidence rate

- IRR:

-

incidence rate ratio

- MTX:

-

methotrexate

- PCP:

-

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- PMS:

-

post-marketing surveillance

- PSL:

-

prednisolone

- PY:

-

patient-year

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- REAL:

-

Japanese Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients on biologics for Long-Term Safety

- SAE:

-

serious adverse event

- SI:

-

serious infection

- TCZ:

-

tocilizumab

- TNFI:

-

tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

References

Mihara M, Kasutani K, Okazaki M, Nakamura A, Kawai S, Sugimoto M, et al. Tocilizumab inhibits signal transduction mediated by both mIL-6R and sIL-6R, but not by the receptors of other members of IL-6 cytokine family. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:1731–40.

Nishimoto N, Kishimoto T. Humanized antihuman IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:151–60.

Maini RN, Taylor PC, Szechinski J, Pavelka K, Broll J, Balint G, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, tocilizumab, in European patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had an incomplete response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2817–29.

Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J. Long-term safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (the STREAM study): evidence of safety and efficacy in a 5-year extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1580–4.

Jones G, Sebba A, Gu J, Lowenstein MB, Calvo A, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Comparison of tocilizumab monotherapy versus methotrexate monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: the AMBITION study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:88–96.

Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, Ramos-Remus C, Rovensky J, Alecock E, et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:987–97.

Garnero P, Thompson E, Woodworth T, Smolen JS. Rapid and sustained improvement in bone and cartilage turnover markers with the anti-interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab plus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate: results from a substudy of the multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab in inadequate responders to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:33–43.

Genovese MC, McKay JD, Nasonov EL, Mysler EF, da Silva NA, Alecock E, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2968–80.

Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, Cantagrel A, van Vollenhoven R, Sanchez A, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1516–23.

Kremer JM, Blanco R, Brzosko M, Burgos-Vargas R, Halland AM, Vernon E, et al. Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to methotrexate: results from the double-blind treatment phase of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab safety and prevention of structural joint damage at one year. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:609–21.

Nishimoto N, Hashimoto J, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, et al. Study of active controlled monotherapy used for rheumatoid arthritis, an IL-6 inhibitor (SAMURAI): evidence of clinical and radiographic benefit from an x ray reader-blinded randomised controlled trial of tocilizumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1162–7.

Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J, et al. Study of active controlled tocilizumab monotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate (SATORI): significant reduction in disease activity and serum vascular endothelial growth factor by IL-6 receptor inhibition therapy. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:12–9.

Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Amano K, Hoshi D, Nawata M, Nagasawa H, et al. Clinical, radiographic and functional effectiveness of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis patients–REACTION 52-week study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1908–15.

Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, Ishiguro N, Ryu J, Takeuchi T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab: postmarketing surveillance of 7901 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:15–23.

Nishimoto N, Ito K, Takagi N. Safety and efficacy profiles of tocilizumab monotherapy in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analysis of six initial trials and five long-term extensions. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:222–32.

Smolen JS, Schoels MM, Nishimoto N, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Dougados M, et al. Consensus statement on blocking the effects of interleukin-6 and in particular by interleukin-6 receptor inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:482–92.

Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509.

Schoels M, Wong J, Scott DL, Zink A, Richards P, Landewe R, et al. Economic aspects of treatment options in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:995–1003.

Schoels M, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, Bijlsma JW, Burmester G, Breedveld FC, et al. Follow-up standards and treatment targets in rheumatoid arthritis: results of a questionnaire at the EULAR 2008. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:575–8.

Schoels M, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, Wong JB. Comparative effectiveness and safety of biological treatment options after tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitor failure in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and indirect pairwise meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1303–8.

Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, Dikranian A, Alten R, Pavelka K, et al. Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1541–50.

Leffers HC, Ostergaard M, Glintborg B, Krogh NS, Foged H, Tarp U, et al. Efficacy of abatacept and tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated in clinical practice: results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1216–22.

Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Maxwell L, Macdonald JK, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2, CD008794.

Yoshida K, Tokuda Y, Oshikawa H, Utsunomiya M, Kobayashi T, Kimura M, et al. An observational study of tocilizumab and TNF-alpha inhibitor use in a Japanese community hospital: different remission rates, similar drug survival and safety. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:2093–9.

Komano Y, Tanaka M, Nanki T, Koike R, Sakai R, Kameda H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a report from the Registry of Japanese Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients for Longterm Safety. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1258–64.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24.

Steinbrocker O, Traeger CH, Batterman RC. Therapeutic criteria in rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Med Assoc. 1949;140:659–62.

Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20.

Sakai R, Komano Y, Tanaka M, Nanki T, Koike R, Nagasawa H, et al. Time-dependent increased risk for serious infection from continuous use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists over three years in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1125–34.

Aringer M, Burkhardt H, Burmester GR, Fischer-Betz R, Fleck M, Graninger W, et al. Current state of evidence on ‘off-label’ therapeutic options for systemic lupus erythematosus, including biological immunosuppressive agents, in Germany, Austria and Switzerland–a consensus report. Lupus. 2012;21:386–401.

Furst DE, Keystone EC, Braun J, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, De Benedetti F, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2011. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:i2–45.

Bykerk VP, Ostor AJ, Alvaro-Gracia J, Pavelka K, Ivorra JA, Graninger W, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to DMARDs and/or TNF inhibitors: a large, open-label study close to clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1950–4.

Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, Ishiguro N, Ryu J, Takeuchi T, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:2148–51.

Lang VR, Englbrecht M, Rech J, Nusslein H, Manger K, Schuch F, et al. Risk of infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:852–7.

Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:189–94.

Genovese MC, Rubbert-Roth A, Smolen JS, Kremer J, Khraishi M, Gomez-Reino J, et al. Longterm safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cumulative analysis of up to 4.6 years of exposure. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:768–80.

Jones G, Ding C. Tocilizumab: a review of its safety and efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;3:81–9.

Campbell L, Chen C, Bhagat SS, Parker RA, Ostor AJ. Risk of adverse events including serious infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:552–62.

Strangfeld A, Eveslage M, Schneider M, Bergerhausen HJ, Klopsch T, Zink A, et al. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time-dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1914–20.

Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K. Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia: associations with prednisone, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:628–34.

Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2294–300.

Dixon WG, Symmons DP, Lunt M, Watson KD, Hyrich KL, Silman AJ. Serious infection following anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from interpreting data from observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2896–904.

Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, Rau R, von Hinueber U, Stoyanova-Scholz M, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3403–12.

Sakai R, Cho SK, Nanki T, Koike R, Watanabe K, Yamazaki H, et al. The risk of serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors decreased over time: a report from the registry of Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics for long-term safety (REAL) database. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:1729–36.

Acknowledgments

The investigators of the REAL study group and their affiliates who contributed to this work were: Tatsuya Atsumi (Hokkaido University); Yoshiaki Ishigatsubo, Atsushi Ihata (Yokohama City University); Tsuneyo Mimori (Kyoto University); Yoshinari Takasaki, Naoto Tamura (Juntendo University); Akira Hashiramoto, Syunichi Shiozawa (Kobe University); Hideto Kameda, Yuko Kaneko, Tsutomu Takeuchi (Keio University); Sae Ochi (Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital); Yasushi Miura (Kobe University); Yoshinori Nonomura (Tokyo Kyosai Hospital); Atsuo Nakajima (Tokyo Metropolitan Police Hospital), Kazuya Michishita, Kazuhiko Yamamoto (The University of Tokyo), Yukitaka Ueki (Sasebo Chuo Hospital), Kenji Nagasaka (Ome Municipal General Hospital); Akitomo Okada, Atsushi Kawakami (Nagasaki University); Shigeto Tohma (Sagamihara National Hospital), Ayako Nakajima, Hisashi Yamanaka (Tokyo Women’s Medical University). We appreciate Ms. Marie Yajima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for her contributions to the maintenance of the REAL database.

Tokyo Women’s Medical University and Yokohama City Minato Red Cross Hospital are also members of the REAL study group, but were not involved in this study. We sincerely thank all the rheumatologists and others caring for RA patients enrolled in the REAL.

Ethical bodies that approved this study are: Hokkaido University, Juntendo University, Kagawa University, Keio University, Kobe University, Kurashiki Kousai Hospital, Kyoto University, Nagasaki University, National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center, Ome Municipal General Hospital, Sagamihara National Hospital, Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University, Sasebo Chuo Hospital, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo Kyosai Hospital, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital, Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital, Tokyo Metropolitan Police Hospital, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, University of Tsukuba, Yokohama City Minato Red Cross Hospital, Yokohama City University.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan (H19-meneki-ippan-009 to N. Miyasaka, H22-meneki-ippann-001 to M. Harigai) and by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (#20390158 to M. Harigai, #19590530 to R. Koike). This work was also supported by grants for pharmacovigilance research on biologics from Abbvie Laboratories, Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol-Myers Japan, Eisai Co. Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., UCB Japan and Pfizer Japan Inc. (to M. Harigai), and by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Global Center of Excellence (GCOE) Program, ‘International Research Center for Molecular Science in Tooth and Bone Diseases.’

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

M. Harigai receives unrestricted research grants for the Department of Pharmacovigilance from Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Japan Inc., Sanofi-Aventis KK., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Teijin Pharma Ltd., and UCB Japan with which TMDU pays salary for R. Sakai, K. Watanabe, H. Yamazaki, M. Tanaka and M. Harigai. T. Nanki has received grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. and Abbvie Inc., personal fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Abbvie Inc., Janssen Pharma K.K. and UCB Japan Co., Ltd. Y. Tanaka has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., and Abbott Japan Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharma K.K., Santen Pharma Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline K.K. Astra-Zaneca, Otsuka Pharma Co., Ltd., Actelion Pharma Japan Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., UCB Japan Co., Ltd., Quintiles Transnational Japan Co. Ltd., Ono Pharma Co., Ltd., and Novartis Pharma K.K and has received research grant support from Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Co., MSD K.K., Astellas Pharma Inc., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Abbott Japan Co., Ltd., and Eisai Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb., and Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. K. Amano has received research support from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co. and Astellas Pharma Inc and has received consulting fees or honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Astellas Pharma Inc., Abbvie Pharmaceutical Research & Development., Eisai Co. Ltd., Pfizer Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb. T. Sumida has received grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Astellas Pharma Inc., others from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb K.K. and Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd. T. Sugihara has received research grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Astellas Pharma Inc. and honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb K.K. and Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd. S. Yasuda has received research grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare-Japan, and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan and honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Co., Bristol-Myers Squibb. T. Sawada has received research grants from Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd., Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., and Ono Pharmaceuticals and consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd., Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ono Pharmaceuticals, and Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. T. Fujii has received research grants from AbbVie GK, Eisai Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K. N. Miyasaka has received research grants from Abbott Japan Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Dainihon-Sumitomo Pharma Co. Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo Co. Ltd., Eisai Co. Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Novartis Pharma K.K., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Teijin Pharma Ltd and received Consulting fee or honorarium from Abbott Japan Co., Ltd., Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceutical KK, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. M. Harigai has received research grants from Abbvie Japan Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Japan Inc., Sanofi-Aventis KK., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and UCB Japan. SK Cho, R. Koike, K. Saito, S. Hirata, H. Nagasawa, T. Hayashi, H. Dobashi, K. Ezawa, A. Ueda, and K. Migita have no financial competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KR, MN, and HM conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. SR and CSK participated in study design, data analysis, coordination and manuscript preparation. NT, WK, YH, TM, KR, TY, SK, HS, AK, NH, SumidaT, HT, SugiharaT, DH, YS, SawadaT, EK, UA, FT, MK, MN, and HM participated in data acquisition, data analysis, and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ryoko Sakai and Soo-Kyung Cho contributed equally to this work.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of RA patients treated with methotrexate at baseline. This file provides demographic and clinical characteristics of RA patients given methotrexate at baseline in this study.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakai, R., Cho, SK., Nanki, T. et al. Head-to-head comparison of the safety of tocilizumab and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis patients (RA) in clinical practice: results from the registry of Japanese RA patients on biologics for long-term safety (REAL) registry. Arthritis Res Ther 17, 74 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0583-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0583-8