Abstract

Background

The genetic architectures of colorectal cancer are distinct across different populations. To date, the majority of polygenic risk scores (PRSs) are derived from European (EUR) populations, which limits their accurate extrapolation to other populations. Here, we aimed to generate a PRS by incorporating East Asian (EAS) and EUR ancestry groups and validate its utility for colorectal cancer risk assessment among different populations.

Methods

A large-scale colorectal cancer genome-wide association study (GWAS), harboring 35,145 cases and 288,934 controls from EAS and EUR populations, was used for the EAS-EUR GWAS meta-analysis and the construction of candidate EAS-EUR PRSs via different approaches. The performance of each PRS was then validated in external GWAS datasets of EAS (727 cases and 1452 controls) and EUR (1289 cases and 1284 controls) ancestries, respectively. The optimal PRS was further tested using the UK Biobank longitudinal cohort of 355,543 individuals and ultimately applied to stratify individual risk attached by healthy lifestyle.

Results

In the meta-analysis across EAS and EUR populations, we identified 48 independent variants beyond genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) at previously reported loci. Among 26 candidate EAS-EUR PRSs, the PRS-CSx approach-derived PRS (defined as PRSCSx) that harbored genome-wide variants achieved the optimal discriminatory ability in both validation datasets, as well as better performance in the EAS population compared to the PRS derived from known variants. Using the UK Biobank cohort, we further validated a significant dose-response effect of PRSCSx on incident colorectal cancer, in which the risk was 2.11- and 3.88-fold higher in individuals with intermediate and high PRSCSx than in the low score subgroup (Ptrend = 8.15 × 10−53). Notably, the detrimental effect of being at a high genetic risk could be largely attenuated by adherence to a favorable lifestyle, with a 0.53% reduction in 5-year absolute risk.

Conclusions

In summary, we systemically constructed an EAS-EUR PRS to effectively stratify colorectal cancer risk, which highlighted its clinical implication among diverse ancestries. Importantly, these findings also supported that a healthy lifestyle could reduce the genetic impact on incident colorectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide, with over 1.8 million new cases and 0.9 million deaths in 2020 [1]. Cumulative evidence has demonstrated that colorectal cancer is caused by environmental factors (e.g., lifestyle), genetic factors, and their interactions [2]. Although environmental risk factors contribute the most, genetic variants can separately explain approximately 7–16% of heritability for colorectal cancer among European (EUR) and East Asian (EAS) populations, indicating the vital role of variants in the development of colorectal cancer [3, 4].

In the past decades, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified over 100 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with the risk of colorectal cancer [5,6,7]. Although each of these risk variants contributes a small effect on colorectal cancer risk, the polygenic risk score (PRS), a method that combines the weak effect of these known or genome-wide variants, has been found to be an efficient tool for identifying individuals at high risk of developing colorectal cancer risk [8,9,10]. However, most PRSs were developed and optimized based on the GWAS data of EUR ancestry and had a limited discriminating ability among other populations (e.g., EAS) [10, 11]. Therefore, it is urgent to construct a trans-ancestry PRS that can improve the ability of colorectal cancer risk prediction in diverse populations.

Unhealthy lifestyles have been known to be associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, while healthy lifestyle habits show inverse associations [12]. In particular, accumulating evidence indicated that among individuals with high genetic risk, cancer risk can be attenuated by adherence to a healthy lifestyle, such as colorectal cancer [13], as well as our previous studies in gastric cancer [14] and lung cancer [15].

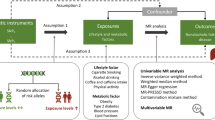

In this study, we performed a large-scale meta-analysis of EAS and EUR populations, to identify common genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer risk across the two ethnic groups. Subsequently, we aimed to develop a novel EAS-EUR PRS that can be used to stratify colorectal cancer risk in diverse populations, and further evaluate the benefit of adherence to a healthy lifestyle stratified by different levels of genetic risk for developing colorectal cancer in a longitudinal cohort (Fig. 1).

Summary of the study design. GWAS, genome-wide association study; EAS, East Asian population; EUR, European population; PRS, polygenic risk score; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian cancer screening trial; GECCO, Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium; CORSA, Colorectal Cancer Study of Austria; BBJ, BioBank Japan Project

Methods

Study participants

Case-control studies of derivation stage

EAS of the Chinese population

The subjects of four independent Chinese colorectal cancer GWAS (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Fig. S1) were recruited from the National ColoRectal Cancer Cohort (NCRCC), including NJCRC GWAS [1316 cases and 2207 controls [16], being part of the Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO)], BJCRC GWAS (932 cases and 966 controls) [17], SHCRC GWAS (1116 cases and 1054 controls), and ZJCRC GWAS (1046 cases and 1184 controls). The detailed information is described in Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials.

EAS of the Japanese population

All participants of the Japanese GWAS were collected in the BioBank Japan Project (BBJ), and the population details have been published in a previous study [18]. We obtained the GWAS summary statistics of colorectal cancer (7062 cases and 195,745 controls) from the JENGER website.

EUR population (GECCO)

The GWAS datasets of GECCO consortia were deposited in the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP, phs001315.v1.p1; phs001415.v1.p1 and phs001078.v1.p1). All cases were confirmed by medical records, pathologic reports, cancer registries, or death certificates. The population details have been published in previous studies [5, 6]. After individual-level quality control (Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials), a total of 21,608 cases and 20,278 controls, which did not include datasets of Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) and Colorectal Cancer Study of Austria (CORSA), were retained for analysis.

EUR population (PLCO)

The PLCO cancer screening trial is a cohort study that aims to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of screening methods for prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer [19], and the detailed information was described in our previous study [20]. We obtained the up-to-date GWAS summary statistics of colorectal cancer (2065 cases and 67,500 controls; October 18, 2022) in the EUR population from the PLCOjs website [21]. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the PLCO consortium providers (#PLCO-84).

Case-control studies of the validation stage

EAS of the Chinese population

The confirmed cases from the JSCRC study were consecutively recruited from hospitals in Jiangsu province, China. The cancer-free control subjects were selected from individuals receiving routine physical examination at hospitals or those participating in community screening for non-communicable diseases in Jiangsu province. A total of 727 cases and 1452 controls were finally included in this study.

EUR population (CORSA)

The CORSA dataset included colorectal cancer and adenoma cases and colonoscopy-negative controls. Controls received a complete colonoscopy and were free of colorectal cancer or polyps [22]. We accessed the CORSA genotype data from dbGaP (phs001415.v1.p1) and kept 1289 cases and 1284 controls for subsequent analysis after the individual-level quality control process (Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials).

Longitudinal cohort of the testing stage

The UK Biobank cohort is a prospective, population-based study, which recruited 502,528 adults aged 40–69 years from the general population between April 2006 and December 2010 [23]. After individual-level quality control (Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials), a total of 355,543 participants were retained for our analysis (Additional file 1: Table S2) [24]. The follow-up time was calculated from baseline assessment to the first diagnosis of colorectal cancer [International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes with C18-C20], loss to follow-up, and death or last follow-up (December 14, 2016). This study was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application #45611.

GWAS meta-analysis of colorectal cancer

The genotyping, imputation, and SNP-level quality control procedures of all GWAS datasets are described in Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials. We used a multivariable logistic regression model to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each SNP with the adjustment of sex, age, and principal components of ancestry, separately for each individual-level GWAS dataset.

We then performed a meta-analysis based on the summary statistics derived from EAS and EUR populations of derivation datasets (35,145 cases and 288,934 controls in total) using the inverse variance-weighted fixed-effects model, implemented by the METAL software [25]. After obtaining the summary statistics of the meta-analysis, we excluded SNPs if they (i) had substantial heterogeneity identified among studies (P value for heterogeneity test < 0.001) and (ii) did not pass filters in both EAS and EUR populations, a total of 4.7 million SNPs were retained for further analysis, and variants at P value < 5 × 10−8 were considered to be genome-wide significant. In the previously reported regions, genome-wide significant SNPs with Pconditional < 5 × 10−8 were considered as novel variants using conditional analysis with the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) software conditioning on the known SNPs [26].

Calculation of PRS

We calculated PRS to aggregate the weak effect of individual SNP [8], based on the following formula: \(\textrm{PRS}=\sum_{i=1}^n{\beta}_i{\textrm{SNP}}_{\textrm{i}}\), where n means the number of SNPs, SNPi and βi are the number of risk alleles (i.e., 0, 1, 2), and weight carried by the ith SNP. The EAS-ancestry (Additional file 1: Table S3) and EUR-ancestry PRSs [10] were constructed using GWAS-reported variants. Furthermore, the development of candidate EAS-EUR PRSs was determined by five different approaches (Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials), including clumping and P value thresholding (i.e., C+T) approach (12 scores) [27], LDpred (11 scores) [28], lassosum (1 score) [29], LDpred2 (1 score) [30], and PRS-CSx methods (1 score) [31]. The 1000 Genomes EAS and EUR populations (Phase 3; 769 individuals) were used as a reference panel. The proportions of the different ethnic groups in the reference panel were consistent with those in the meta-analysis of EAS and EUR GWASs.

Calculation of lifestyle score

We calculated healthy lifestyle scores based on the eight lifestyle factors [32], including body mass index (BMI), tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), physical activity, sedentary time, red and processed meat intake, and vegetable and fruit intake (Additional file 1: Table S4). Each lifestyle factor was given a score of 0 or 1, with 1 representing the healthy behavior category, and the sum of the eight scores was used as the healthy lifestyle score. The detailed information is described in Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials.

Estimation of 5-year absolute risk

We estimated individual 5-year absolute risk for developing colorectal cancer by combining the relative risk (incorporating genetic risk and lifestyle) with the incidence rate of colorectal cancer and the mortality rate for all causes except for colorectal cancer [9], and the exact details of the calculations were described in our previous study [16].

Statistical analysis

The population structure was estimated using the EIGENSOFT software [33], and the Manhattan plot and quantile-quantile plot based on the -log10 (P value) were created by using the R package qqman (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/qqman/index.html). We evaluated the discriminatory ability of PRSs derived from different approaches described above using the crude and covariates-adjusted area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) via the R package RISCA [34].

In the UK Biobank cohort, the Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs after adjusting for corresponding confounding factors. We compared the difference in the distribution of PRS between two or more groups by the Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Participants were classified into ten equal subgroups according to the decile distribution of PRS and categorized into low (bottom 10%), intermediate (10–90%), and high genetic risk (top 10%) subgroups for group comparisons. Similarly, participants were classified into unfavorable (0 and 1 score), intermediate (2 and 3 score), and favorable (≥ 4 score) lifestyle subgroups based on lifestyle scores ranging from 0 to 8. The log-rank test was used to evaluate the difference in cumulative incidence (one minus the Kaplan-Meier estimate) stratified by different levels of PRS or lifestyle scores. The incidence proportion and 95% CI in each group were estimated by the exact Poisson test. The R package Shiny (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/shiny/) was used to construct the colorectal cancer risk prediction web server, which was freely available and open source.

In addition, to assess the robustness of the results, we performed the following sensitivity analyses: (i) excluded incident colorectal cancer cases that had occurred during the first year of follow-up; (ii) evaluated the associations using ancestry-corrected PRS: briefly, fit a linear regression model using the first ten principal components of ancestry to predict PRS, and the residual from this model was used to create ancestry-corrected PRS; (iii) healthy lifestyle categories were reclassified to unfavorable (0, 1, and 2 score), intermediate (3 and 4 score), and favorable (≥ 5 score) lifestyle groups; and (iv) excluded non-colorectal cancer participants with other cancers that occurred during the time of follow-up.

All other statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 3.6.1, https://cran.r-project.org/), and a two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

EAS-EUR GWAS meta-analysis of colorectal cancer

The combined EAS-EUR GWAS dataset of colorectal cancer comprised a total of 35,145 cases and 288,934 controls, and there was no residual population stratification observed via genomic control inflation factors (lambda = 1.002; Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

In total, we identified 48 independent SNPs [linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 < 0.1] that were significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk beyond genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8; Table 1; Additional file 1: Fig. S3). We found that all of these SNPs were located within 1 Mb of well-identified regions reported by previous GWASs, while one novel risk variant (LD r2 < 0.1 with the previously reported SNPs) was found to be independently associated with colorectal cancer risk in conditional analyses on GWAS-reported risk variants [rs7623129 (3p14.1), ORconditional = 1.06, Pconditional = 1.18 × 10−8; Additional file 1: Table S5]. Especially, functional annotation showed that rs7623129 overlapped with the enhancer histone mark and DNAse hypersensitivity site, indicating that it may be involved in the development of colorectal cancer by regulating the expression of nearby ADAMTS9 (Additional file 1: Table S6).

PRS calculation and validation in the independent datasets

Subsequently, we aimed to construct and validate a novel PRS for colorectal cancer risk stratification by incorporating EAS and EUR populations. As shown in Table 2, although the EUR-ancestry PRS showed great discriminatory ability in the EUR population (i.e., CORSA dataset; AUCcrude = 0.629, AUCadjust = 0.638), its performance in the EAS population (i.e., JSCRC dataset; AUCcrude = 0.511, AUCadjust = 0.510) was limited. Similar results were also found in EAS-ancestry PRS, demonstrating the limited transferability of single-ancestry PRS in other populations.

Among the 26 developed EAS-EUR PRSs, twenty were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer in the JSCRC GWAS of EAS ancestry [OR per standard deviation (SD) increase ranged from 1.29 (P = 8.02 × 10−8) for C+T (P value and LD r2: 5 × 10−8 and 0.01) to 1.73 (P = 7.19 × 10−27) for PRS-CSx], as well as in the CORSA GWAS of EUR ancestry [OR per SD ranged from 1.21 (P = 4.89 × 10−6) for C+T (P value and LD r2: 0.05 and 0.01) to 1.48 (P = 5.18 × 10−19) for PRS-CSx; Table 2]. Notably, the PRS-CSx approach-based PRS that harbored genome-wide 1,145,689 SNPs (defined as PRSCSx) achieved the optimal discriminatory ability for distinguishing cases from healthy controls in both validation datasets (JSCRC dataset: AUCcrude = 0.639, AUCadjust = 0.646; Additional file 1: Fig. S4; CORSA dataset: AUCcrude = 0.602, AUCadjust = 0.608; Additional file 1: Fig. S5). Especially, when compared with known variant-derived PRS, the PRSCSx showed better predictive performance in the EAS population than both EUR-ancestry (AUCadjust: 0.646 vs. 0.510) and EAS-ancestry PRSs (AUCadjust: 0.646 vs. 0.580), although it had a marginally weaker predictive ability in EUR population than EUR-ancestry PRS (AUCadjust: 0.608 vs. 0.638).

PRS test in the UK Biobank cohort

We further evaluated the performance of the optimal PRSCSx for colorectal cancer risk prediction in the UK Biobank cohort, in which 2621 colorectal cancer cases among 355,543 individuals were confirmed during a median follow-up of 7.88 years. As expected, colorectal cancer cases had a higher PRSCSx value than those without colorectal cancer [HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.37 to 1.48 per SD increase, P = 3.53 × 10−72, Additional file 1: Table S7; PWilcoxon < 2 × 10−16; Additional file 1: Fig. S6A]. Importantly, PRSCSx had a stable discriminatory ability with an AUC of 0.595 (for crude AUC) and 0.597 (for covariates-adjusted AUC; Additional file 1: Fig. S6B), similar with that in the validation dataset of EUR ancestry. Notably, there was a dose-response effect of PRSCSx on developing colorectal cancer at both decile classification (Ptrend = 1.57 × 10−56; Additional file 1: Fig. S6C) and three-category classification (intermediate vs. low: HR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.76 to 2.54, P = 1.30 × 10−15; high vs. low: HR = 3.88, 95% CI = 3.18 to 4.74, P = 2.82 × 10−40; Ptrend = 8.15 × 10−53; Additional file 1: Table S7; log-rank P < 2 × 10−16; Fig. 2A). Besides, we observed similar findings underlying the sensitivity analyses (Additional file 1: Table S8).

The cumulative risk of developing colorectal cancer according to the PRS and lifestyle score in the UK Biobank cohort. A Cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer in the low, intermediate, and high PRS groups. B Cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer in unfavorable, intermediate, and favorable lifestyle groups. C Cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer stratified by different levels of PRS and lifestyle score. D The associations of PRS and lifestyle score with incident colorectal cancer. The HR and 95% CI were derived from the Cox regression model with the adjustment of sex, age, center, and first 10 principal components. PRS, polygenic risk score; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals

Evaluation of the benefit of adherence to a healthy lifestyle stratified by genetic risk

In the UK Biobank cohort, several healthy lifestyle factors were associated with a decreased risk of colorectal cancer; for example, compared to smokers, non-smokers had a 0.18-fold reduced risk of developing colorectal cancer (OR = 0.82, P = 3.58 × 10−7; Additional file 1: Table S4). Furthermore, we noticed a significantly protective effect of combined lifestyle score in a dose-response manner on colorectal cancer development at both continuous levels (HR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.88 to 0.93 per lifestyle score increase, P = 3.39 × 10−12; Additional file 1: Table S9) and stratified levels (intermediate vs. unfavorable: HR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.72 to 0.87, P = 2.86 × 10−6; favorable vs. unfavorable: HR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.58 to 0.74, P = 2.56 × 10−12; Ptrend = 1.92 × 10−12; log-rank P < 2 × 10−16; Fig. 2B). Similar findings were observed in the sensitivity analyses (Additional file 1: Table S10). Intriguingly, there was an inverse relationship between the PRSCSx and several lifestyle factors (PWilcoxon < 0.05; Additional file 1: Fig. S7A) or the lifestyle score (PKruskal-Wallis = 1.60 × 10−8; Pchi-square = 9.83 × 10−7; Additional file 1: Fig. S7B-C), but their effects on colorectal cancer risk were not mutually influenced (Additional file 1: Tables S7-10).

Therefore, we further evaluated the joint effect of genetic and lifestyle factors on the risk for incident colorectal cancer. As expected, there was a notable dose-response manner on increasing colorectal cancer risk as PRSCSx increased and lifestyle score decreased (trend to unfavorable lifestyle) (log-rank P < 2 × 10−16; Fig. 2C, D), but no multiplicative interaction between genetic risk and lifestyle score was observed (Pinteraction = 0.539). Interestingly, when stratifying individuals by PRSCSx categories, we observed that a healthy lifestyle could still be significantly associated with a reduced risk of developing colorectal cancer broadly, regardless of the genetic risk effect (low: Ptrend = 0.043, intermediate: Ptrend = 7.18 × 10−11, high: Ptrend = 0.077; Table 3). Similar trends were found in the sensitivity analyses (Additional file 1: Table S11).

Estimation of 5-year absolute risk

Subsequently, we estimated the 5-year absolute risk of developing colorectal cancer using a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors and observed that colorectal cancer patients had a higher 5-year absolute risk than those without colorectal cancer (PWilcoxon < 2 × 10−16; Additional file 1: Fig. S8A). Especially when stratified by age group, a higher 5-year absolute risk was observed in individuals carrying a high genetic risk or an unfavorable lifestyle (PKruskal-Wallis < 2 × 10−16; Additional file 1: Fig. S8B-C). Furthermore, in the stratification by genetic risk (Table 3 and Fig. 3A), there was a significant risk reduction in individuals with a low PRS and a favorable lifestyle (risk = 0.14%, reduction = 0.14%) compared with those with a low PRS but an unfavorable lifestyle (risk = 0.28%), and among individuals with a high PRS, the risk of an unfavorable lifestyle increased to 1.07%, which could be reduced to 0.54% among those with a favorable lifestyle (reduction = 0.53%).

Estimation of 5-year absolute risk for colorectal cancer in the UK Biobank cohort. A The 5-year absolute risk of developing colorectal cancer defined by different levels of PRS and lifestyle score. B The associations between different levels of 5-year absolute risk and incident colorectal cancer. The HR and 95% CI were derived from the Cox regression model with the adjustment of center and first 10 principal components. PRS, polygenic risk score; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals

Construction of ColoRectal Cancer Risk Prediction System (CRC-RPS)

Furthermore, we stratified the risk population according to the median value (0.34%; as a reference threshold) and two times the threshold (0.68%) of 5-year absolute risk among individuals without colorectal cancer, which was defined as low (< 0.34%), intermediate (0.34 to 0.68%) and high risk (> 0.68%). As expected, both intermediate- and high-risk populations had a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer than the low-risk population (intermediate: HR = 2.47, 95% CI = 2.21 to 2.75; high: HR = 4.30, 95% CI = 3.87 to 4.78; Fig. 3B). To friendly apply our findings, we developed a colorectal cancer risk prediction web server, CRC-RPS, to help users estimate their 5-year absolute risk of developing colorectal cancer by combining genetic and lifestyle factors (http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/CRC-RPS/). In brief, users can easily input their sex, age, and lifestyle information along with the genotypes of 1.15 million SNPs to obtain an estimated 5-year absolute risk and the assigned risk-population group. For example, a user with a predicted 0.2% of 5-year absolute risk was grouped as low risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Discussion

In the present study, we comprehensively constructed several sets of EAS-EUR PRSs based on the large-scale GWAS data of colorectal cancer across EAS and EUR populations and subsequently found a solid PRS framework (i.e., PRSCSx) derived from genome-wide SNPs, independent of individual lifestyle, for stratifying the risk populations of developing colorectal cancer evidenced by independent validation datasets and a longitudinal cohort. Importantly, even though there was diversity in genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle behavior could consistently reduce the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

In recent decades, convincing evidence has emerged suggesting that identifying high-risk individuals can enable enhanced screening and the application of other interventions, thereby reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer [35]. Therefore, researchers have paid more attention to the clinical use of PRS, by determining whether it can stratify populations into subgroups with a distinct risk of developing diseases for early interventions [8, 36]. To date, multiple PRSs have been constructed and confirmed to have a discriminatory ability in distinguishing colorectal cancer cases from healthy controls [9, 10, 37]. However, most PRSs were derived from individuals of EUR ancestry, which might limit their application in other ethnic populations. Cumulative evidence has demonstrated that, when applying the PRS models trained with EUR individuals to other ethnic populations, there were less accurate compared to EUR populations [11, 38]. In particular, Thomas et al. found that the PRS model of colorectal cancer derived from 120,184 subjects of EUR ancestry performed worse for Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans than for Europeans [10]. These findings highlighted the need to reconsider the model performance when applying PRS to non-European ancestry and bolstered the rationale for trans-ancestry PRS in diverse populations. Here, we built a novel PRSCSx across EAS and EUR populations and validated that this PRS could significantly predict the risk of developing colorectal cancer in two ethnic groups; importantly, the high PRS group could be used in colorectal cancer screening for personalized prevention.

Although the performance of our PRS in the EUR population (e.g., CORSA dataset) is substantially lower than previous EUR-ancestry PRSs (e.g., Thomas et al.’s genome-wide PRS) [10], our aim was to improve the clinical utility of PRS in multiple ethnic groups, especially for non-EUR (e.g., EAS) populations. As evidenced in a recent trans-ancestry PRS study, when the target population was EUR population, the improvement of multi-ancestry PRS over EUR-ancestry PRS was limited; however, when predicting into EAS populations, multi-ancestry PRS clearly outperformed EUR-ancestry PRS [31], which was also found in our study. Therefore, the advantage of our PRS compared to EUR-ancestry PRSs should be further validated in independent EAS longitudinal cohorts.

A healthy lifestyle has been known to be associated with a decreased risk of colorectal cancer. For instance, Kirkegaard et al. found that 23% of colorectal cancer cases might be caused by a lack of adherence to five lifestyle recommendations in a prospective Danish cohort study with 55,487 participants [39]. In our study, another important finding was that the detrimental effect of high genetic risk on incident colorectal cancer could be largely attenuated by adherence to a healthy lifestyle, which was consistent with previous findings [13, 32, 40]. Moreover, although the 5-year absolute risk associated with adherence to a healthy lifestyle was greatest in the group at high genetic risk, our results still emphasize the notion that the public senses of a healthy lifestyle in the whole population will lead to an evident reduction in colorectal cancer risk.

This study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to develop an EAS-EUR PRS with a sufficient sample size, followed by the performance evaluation on incident colorectal cancer risk via external case-control studies and prospective cohort. This study provided further genetic information supporting the contribution of germline variation to ancestry disparity in the development of colorectal cancer. Second, we constructed a user-friendly web server to help generate a customized estimate of risk for developing colorectal cancer, for use as an early screening method. Nevertheless, we acknowledge several limitations. First, we need to validate the predictive ability of this novel PRS in an independent EAS longitudinal cohort with sufficient samples. Second, we currently focus on EAS and EUR populations in this study, and other populations (e.g., African Americans and Hispanics) need to be included in future work. Third, the limited model performance in the EUR population needs to be further improved using a larger sample size in the training set, as well as more sophisticated trans-ancestry PRS methods.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we applied an EAS-EUR combined approach to construct a PRS framework derived from genome-wide SNPs that can effectively predict colorectal cancer risk, which reduced the gap in genetic risk prediction between diverse populations. Importantly, these findings also provided further evidence that a healthy lifestyle can attenuate the genetic impact on incident colorectal cancer.

Availability of data and materials

BBJ colorectal cancer GWAS summary statistics are publicly available on the JENGER website (http://jenger.riken.jp/en/result). GWAS summary statistics from the GECCO study are available on the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; Study Accession: phs001315.v1.p1; phs001415.v1.p1 and phs001078.v1.p1). GWAS summary statistics from the PLCO study are publicly available on the PLCOjs website (https://episphere.github.io/plco/#). Individual-level data from the UK Biobank cohort are available through the UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/) application. The genotype data from the Chinese population cannot be submitted to publicly available databases because the ethical approval did not permit the sharing of raw genotype data. But the data can be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author in accordance with the Chinese genomic data sharing policy. The SNP effect size estimates for the PRSCSx are available at http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/CRC-RPS/ and are deposited in the PGS Catalog (https://www.pgscatalog.org; PGS ID: PGS003395).

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(12):713–32.

Dai J, Shen W, Wen W, Chang J, Wang T, Chen H, et al. Estimation of heritability for nine common cancers using data from genome-wide association studies in Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(2):329–36.

Jiao S, Peters U, Berndt S, Brenner H, Butterbach K, Caan BJ, et al. Estimating the heritability of colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(14):3898–905.

Huyghe JR, Bien SA, Harrison TA, Kang HM, Chen S, Schmit SL, et al. Discovery of common and rare genetic risk variants for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2019;51(1):76–87.

Peters U, Jiao S, Schumacher FR, Hutter CM, Aragaki AK, Baron JA, et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility loci for colorectal tumors in a genome-wide meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(4):799–807.

Buniello A, Macarthur J, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D1005–12.

Torkamani A, Wineinger NE, Topol EJ. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(9):581–90.

Jeon J, Du M, Schoen RE, Hoffmeister M, Newcomb PA, Berndt SI, et al. Determining risk of colorectal cancer and starting age of screening based on lifestyle, environmental, and genetic factors. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(8):2152–64.

Thomas M, Sakoda LC, Hoffmeister M, Rosenthal EA, Lee JK, van Duijnhoven F, et al. Genome-wide modeling of polygenic risk score in colorectal cancer risk. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107(3):432–44.

Duncan L, Shen H, Gelaye B, Meijsen J, Ressler K, Feldman M, et al. Analysis of polygenic risk score usage and performance in diverse human populations. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3328.

Murphy N, Moreno V, Hughes DJ, Vodicka L, Vodicka P, Aglago EK, et al. Lifestyle and dietary environmental factors in colorectal cancer susceptibility. Mol Aspects Med. 2019;69:2–9.

Carr PR, Weigl K, Jansen L, Walter V, Erben V, Chang-Claude J, et al. Healthy lifestyle factors associated with lower risk of colorectal cancer irrespective of genetic risk. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1805–15.

Jin G, Lv J, Yang M, Wang M, Zhu M, Wang T, et al. Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):1378–86.

Dai J, Lv J, Zhu M, Wang Y, Qin N, Ma H, et al. Identification of risk loci and a polygenic risk score for lung cancer: a large-scale prospective cohort study in Chinese populations. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(10):881–91.

Xin J, Du M, Gu D, Ge Y, Li S, Chu H, et al. Combinations of single nucleotide polymorphisms identified in genome-wide association studies determine risk for colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(10):2661–9.

Jiang K, Sun Y, Wang C, Ji J, Li Y, Ye Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 5q23.3 and 17q12 in Han Chinese. Oncotarget. 2015;6(37):40327–36.

Ishigaki K, Akiyama M, Kanai M, Takahashi A, Kawakami E, Sugishita H, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study in a Japanese population identifies novel susceptibility loci across different diseases. Nat Genet. 2020;52(7):669–79.

Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Greenwald P, Kramer BS. The PLCO Cancer Screening Trial: background, goals, organization, operations, results. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2015;10(3):173–80.

Chu H, Xin J, Yuan Q, Wu Y, Du M, Zheng R, et al. A prospective study of the associations among fine particulate matter, genetic variants, and the risk of colorectal cancer. Environ Int. 2021;147:106309.

Ruan E, Nemeth E, Moffitt R, Sandoval L, Machiela MJ, Freedman ND, et al. PLCOjs, a FAIR GWAS web SDK for the NCI Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Genetic Atlas Project. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(18):4434–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac531.

Hofer P, Baierl A, Feik E, Fuhrlinger G, Leeb G, Mach K, et al. MNS16A tandem repeats minisatellite of human telomerase gene: a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(6):866–71.

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. Plos Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779.

Xin J, Jiang X, Ben S, Yuan Q, Su L, Zhang Z, et al. Association between circulating vitamin E and ten common cancers: evidence from large-scale Mendelian randomization analysis and a longitudinal cohort study. Bmc Med. 2022;20(1):168.

Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–1.

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82.

Choi SW, Mak TS, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(9):2759–72.

Vilhjalmsson BJ, Yang J, Finucane HK, Gusev A, Lindstrom S, Ripke S, et al. Modeling linkage disequilibrium increases accuracy of polygenic risk scores. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(4):576–92.

Mak T, Porsch RM, Choi SW, Zhou X, Sham PC. Polygenic scores via penalized regression on summary statistics. Genet Epidemiol. 2017;41(6):469–80.

Prive F, Arbel J, Vilhjalmsson BJ. LDpred2: better, faster, stronger. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:5424–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1029.

Ruan Y, Lin YF, Feng YA, Chen CY, Lam M, Guo Z, et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat Genet. 2022;54(5):573–80.

Choi J, Jia G, Wen W, Shu XO, Zheng W. Healthy lifestyles, genetic modifiers, and colorectal cancer risk: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(4):810–20.

Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. Plos Genet. 2006;2(12):e190.

Janes H, Pepe MS. Adjusting for covariates in studies of diagnostic, screening, or prognostic markers: an old concept in a new setting. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(1):89–97.

Dekker E, Rex DK. Advances in CRC prevention: screening and surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(7):1970–84.

Lewis CM, Vassos E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):44.

Hsu L, Jeon J, Brenner H, Gruber SB, Schoen RE, Berndt SI, et al. A model to determine colorectal cancer risk using common genetic susceptibility loci. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1330–9.

Ma Y, Zhou X. Genetic prediction of complex traits with polygenic scores: a statistical review. Trends Genet. 2021;37(11):995–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2021.06.004.

Kirkegaard H, Johnsen NF, Christensen J, Frederiksen K, Overvad K, Tjonneland A. Association of adherence to lifestyle recommendations and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective Danish cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5504.

Carr PR, Weigl K, Edelmann D, Jansen L, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H, et al. Estimation of absolute risk of colorectal cancer based on healthy lifestyle, genetic risk, and colonoscopy status in a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):129–38.

Acknowledgements

We thank BBJ, GECCO, PLCO cancer screening trial (Application #PLCO-84), and UK Biobank cohort (Application #45611) for sharing colorectal cancer GWAS data. We also thank Qingyi Wei (Duke University School of Medicine and Duke Cancer Institute, USA) for the helpful comments.

Funding

This study/project is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81822039, 82173601, and 82073631), the Gusu Health Talent Program (GSWS2021034), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (Public Health and Preventive Medicine). The funder had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MW supervised the entire project. MW, JX, and MD contributed to the data interpretation, data analysis, and writing of the draft. DG, KJ, MW, MJ, YH, SB, SC, WS, SL, HC, LZ, CL, KC, KD, ZZ, and HS contributed to the study design, sample collection, and experiment or data interpretation. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. Our study was approved by the local internal review boards or ethics committees (Nanjing Medical University). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Basic characteristics of colorectal cancer GWASs. Table S2. Basic characteristics of the UK Biobank cohort. Table S3. Summary of 37 colorectal cancer GWAS-reported SNPs in East Asian. Table S4. Summary of eight lifestyle factors in the UK Biobank cohort. Table S5. Summary of one novel EAS-EUR conditionally independent variant at known colorectal cancer risk loci. Table S6. Functional annotations of one novel colorectal cancer risk locus. Table S7. The association of PRS with colorectal cancer risk in the UK Biobank. Table S8. Sensitivity analyses for the association of PRS with colorectal cancer risk in the UK Biobank cohort. Table S9. The association of lifestyle score with colorectal cancer risk in the UK Biobank cohort. Table S10. Sensitivity analyses for the association of lifestyle score with colorectal cancer risk in the UK Biobank cohort. Table S11. Sensitivity analyses for cumulative risk of developing colorectal cancer according to different levels of PRS and lifestyle score in the UK Biobank cohort. Fig. S1. Principal component analysis based on the colorectal cancer GWAS subjects and 1000 Genomes Project populations. Fig. S2. Quantile-quantile plot and genomic inflation factor for the association with colorectal cancer risk in the meta-analysis of EAS-EUR GWASs. Fig. S3. Manhattan plot from colorectal cancer EAS-EUR GWAS meta-analysis. Fig. S4. The association of PRSCSx with incident colorectal cancer in the JSCRC GWAS dataset. Fig. S5. The association of PRSCSx with incident colorectal cancer in the CORSA GWAS dataset. Fig. S6. The association of PRS with incident colorectal cancer in the UK Biobank cohort. Fig. S7. The association of PRS with lifestyle factors in the UK Biobank cohort. Fig. S8. Distribution of 5-year absolute risk of developing colorectal cancer in the UK Biobank cohort.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, J., Du, M., Gu, D. et al. Risk assessment for colorectal cancer via polygenic risk score and lifestyle exposure: a large-scale association study of East Asian and European populations. Genome Med 15, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-023-01156-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-023-01156-9