Abstract

Background

Mitochondrial presequence proteases perform fundamental functions as they process about 70 % of all mitochondrial preproteins that are encoded in the nucleus and imported posttranslationally. The mitochondrial intermediate presequence protease MIP/Oct1, which carries out precursor processing, has not yet been established to have a role in human disease.

Methods

Whole exome sequencing was performed on four unrelated probands with left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC), developmental delay (DD), seizures, and severe hypotonia. Proposed pathogenic variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing or array comparative genomic hybridization. Functional analysis of the identified MIP variants was performed using the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae as the protein and its functions are highly conserved from yeast to human.

Results

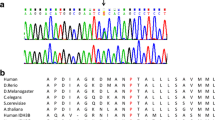

Biallelic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or copy number variants (CNVs) in MIPEP, which encodes MIP, were present in all four probands, three of whom had infantile/childhood death. Two patients had compound heterozygous SNVs (p.L582R/p.L71Q and p.E602*/p.L306F) and one patient from a consanguineous family had a homozygous SNV (p.K343E). The fourth patient, identified through the GeneMatcher tool, a part of the Matchmaker Exchange Project, was found to have inherited a paternal SNV (p.H512D) and a maternal CNV (1.4-Mb deletion of 13q12.12) that includes MIPEP. All amino acids affected in the patients’ missense variants are highly conserved from yeast to human and therefore S. cerevisiae was employed for functional analysis (for p.L71Q, p.L306F, and p.K343E). The mutations p.L339F (human p.L306F) and p.K376E (human p.K343E) resulted in a severe decrease of Oct1 protease activity and accumulation of non-processed Oct1 substrates and consequently impaired viability under respiratory growth conditions. The p.L83Q (human p.L71Q) failed to localize to the mitochondria.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal for the first time the role of the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase in human disease. Loss of MIP function results in a syndrome which consists of LVNC, DD, seizures, hypotonia, and cataracts. Our approach highlights the power of data exchange and the importance of an interrelationship between clinical and research efforts for disease gene discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) is a heterogeneous disorder that may present with heart failure, arrhythmia, and systemic embolism [1]. Failure to develop compact myocardium in the early embryo results in LVNC with the underlying genetic basis identified in around 30–50 % of individuals with LVNC [1]. Different modes of inheritance have been described for LVNC, including autosomal dominant, X-linked, and mitochondrial inheritance. Among them, the most prevalent form is the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (70 % of all cases where the genetic basis is known) with incomplete penetrance [1, 2].

Mechanisms that have been implicated in LVNC include variants in genes encoding the substructures of the sarcomere in cardiomyocytes. For example, variants in MYH7 (MIM 613426) and MYBPC3 (MIM 615396) both lead to a disruption of myosin function [3, 4]. Additionally, variants in ACTC1 (MIM 613424), TNNT2 (MIM 601494), TPM1 (MIM 611878) and DTNA (MIM 604169) cause dysfunction of actin, troponin, tropomyosin, and dystrobrevin, respectively [4–7]. Moreover, variants in LDB3 (MIM 601493), a gene that plays a role in the maintenance of structural integrity of cardiomyocytes, has been associated with LVNC [8]. Recently, variants in MIB1 (MIM 615092) have been identified to cause abnormal cardiac trabeculations through dysregulation of the NOTCH pathway [9]. Furthermore, truncations and missense variants of TAZ (MIM 302060), a mitochondrial transacylase, have been associated with X-linked dominant LVNC in male patients with Barth syndrome [7, 10]. In many cases of LVNC, however, the underlying genetic bases remain unknown.

We have identified several single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in MIPEP in patients with LVNC. Using whole exome sequencing (WES), a homozygous missense SNV in MIPEP was identified in a child from a consanguineous family, two compound heterozygous SNVs were found in individuals from two unrelated, non-consanguineous families, and a paternally inherited SNV and maternally inherited 1.4-Mb deletion copy number variant (CNV) was found in a fourth child. Although the aforementioned searches were based upon finding damaging variants in the same gene, remarkably the predominant clinical features shared by all four subjects included LVNC, developmental delay (DD), seizures, and hypotonia; three experienced infantile/early childhood death secondary to cardiomyopathy.

MIPEP encodes the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIP in human, Oct1 in yeast) [11–13]. A vast majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded by the nuclear DNA. These mitochondrial preproteins are then translated on cytosolic ribosomes and imported post-translationally. Approximately 70 % of these preproteins use N-terminal targeting signals (presequences) for import and translocation across the mitochondrial membranes [14]. Upon entry into the mitochondrial matrix these presequences are cleaved by specialized proteases, the mitochondrial presequence proteases. The major part of the presequence is cleaved by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP). However, approximately one quarter of preproteins require a secondary processing that is carried out by the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase MIP/Oct1 or mitochondrial X-prolyl aminopeptidase 3 (XPNPEP3), also known as intermediate cleaving peptidase Icp55 in yeast and plants [13–16]. MIP/Oct1 removes an additional octapeptide after MPP cleavage (Fig. 1), while XPNPEP3/Icp55 removes a single amino acid [16]. All proteases involved in presequence cleavage are highly conserved from yeast to human, evidence of their fundamental role in mitochondrial biogenesis.

Import of nuclear-encoded proteins into mitochondria and their processing. This process is guided by N-terminal presequences that direct import across the mitochondrial outer and inner membranes through translocons. Precursor processing by MPP and MIP/Oct1 removes the presequence and an additional octapeptide resulting in the mature, stable protein

MIPEP (MIM 602241, NM_005932) [17, 18] is comprised of 19 exons and maps to chromosome 13q12.12 [19]. MIP is expressed at high levels in heart, brain, skeletal muscle, and pancreas, all tissues that require a significant amount of energy and therefore are dependent on efficient mitochondrial ATP production [19–21]. Furthermore, these tissues are often affected in individuals with various mitochondrial disorders, including MELAS (MIM 540000) and Pearson marrow-pancreas syndrome (MIM 557000) [22, 23]. A broad range of cardiomyopathy disorders have been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction [21, 24, 25]. Here, we report a clinical syndrome of LVNC, DD, seizures, hypotonia, cataracts, and infantile death associated with MIPEP dysfunction.

Methods

Sequencing

The first three patients initially had clinical WES performed in the Whole Genome Laboratory (WGL), a part of Baylor Genetics Laboratories at Baylor College of Medicine [26]. The coding exons of approximately 20,000 genes were targeted by WES [26, 27] with 130× average depth-of-coverage and >95 % of the targeted bases with >20 reads. The post-processing of raw sequence data was performed using the Mercury pipeline [28]. First, the raw sequencing data (bcl files) were converted to fastq files using Casava. Next, mapping of short reads to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37) was performed by the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA) tool. Recalibration and variant calling were then performed using GATK [29] and the Atlas2 suite, respectively [30]. The Mercury pipeline is available in the cloud via DNANexus (http://blog.dnanexus.com/2013-10-22-run-mercury-variant-calling-pipeline/). Any individuals or families in whom clinical WES did not identify a molecular diagnosis in known human disease genes were contacted for possible enrollment in the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (BHCMG) Project for further research analysis of WES data and/or WES of additional family members. The first patient enrolled in the BHCMG Project had MIPEP prioritized as a potential candidate gene based on the clinical impression of a mitochondrial disorder. Upon further communication with the clinical exome laboratory, two additional individuals with biallelic variants in MIPEP were identified and found clinically to have been referred with a diagnosis of LVNC cardiomyopathy (although the phenotype was not a criteria for the search). The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Baylor College of Medicine. Additionally, we Sanger sequenced MIPEP in 11 individuals aged younger than 5 years with cardiomyopathy and unknown molecular diagnoses at the Baylor Genetics Laboratory.

Experimental methods

Yeast strains and growth conditions

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are derived from BY4741 oct1Δ (Mata; his3Δ1; leu2Δ0; met15Δ0; ura3Δ0; YKL134c::kanMX4) and YPH499 (MATa, ade2-101, his3-∆200, leu2-∆1, ura3-52, trp1-∆63, lys2-801). For re-expression of Oct1 in the oct1Δ strain, the open reading frame under its endogenous promoter and terminator region was cloned into the pRS413 expression vector [12]. Mutations were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis. All plasmids were sequenced and subjected to in vitro transcription/translation in the presence of [35S]methionine and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography as quality control. The obtained strains were grown on minimal medium (6.7 % (w/v) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2 % glucose (w/v), 0.77 % Complete Supplement Mixture minus histidine).

Mutant generation by plasmid shuffling

To enable analysis of mutations in vivo under respiratory conditions, the Oct1 protein was expressed from the pRS416 plasmid (ura3). Subsequently, the genomic copy of OCT1 was deleted by homologous recombination. The strain was then transformed with a plasmid encoding Oct1 (pRS413_Oct1) or Oct1 with point mutations resulting in the following amino acid exchanges: L83Q, L339F, K376E, N575D, L645R, and N666* (Additional file 1: Figure S1). All OCT1 variants were expressed under the endogenous OCT1 promoter and terminator regions and carried a C-terminal HA tag. When the cells are grown on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), the ura3 gene product converts the 5-FOA into a toxic compound and the cells are selected for pRS416 plasmid loss (plasmid shuffling). Transformation with pRS413_Oct1N575D, pRS413_Oct1L645R and pRS413_Oct1N666* did not result in viable yeast cells. Of the obtained yeast strains expressing Oct1 mutants L83Q, L339F, and K376E, five independent clones of each mutant and four independent clones of the wild type (OctWT) were tested for growth defects. All clones analyzed showed the same growth behavior. Two to three clones were selected and mitochondria isolated, all of which showed the accumulation of processing intermediates of Oct1 substrates.

For growth tests yeast cells were grown overnight in 5 ml YPG medium at 24 °C. Cell numbers (OD600) were measured and adjusted and tenfold serial dilutions were spotted on YPD and YPG agar plates. Plates were incubated at the indicated temperatures.

Isolation of mitochondria

For isolation of mitochondria, cells were grown at 24 °C on fermentable medium (1 % (w/v) yeast extract, 2 % (w/v) bacto peptone, 2 % (w/v) sucrose, pH 5.0) or non-fermentable medium (3 % (w/v) glycerol instead of sucrose). Strains expressing the mutant Oct1 proteins (L339F, K376E) were shifted for 10 h to 37 °C prior to isolation of mitochondria. Cells were harvested in the logarithmic growth phase (OD600 1.0–1.5) and mitochondria isolated by differential centrifugation as described previously [31]. Aliquots were stored in SEM buffer (250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2) at −80 °C. Protein levels were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunodecoration according to standard protocols.

In organello import and processing of Oct1 substrate proteins

Radiolabeled precursor proteins were generated by in vitro transcription/translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine and incubated with 50 μg isolated mitochondria for the indicated time periods in import buffer (10 mM MOPS/KOH, pH 7.2, 3 % (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 80 mM KCL, 5 mM KPi, 2 mM ATP, and 2 mM NADH) [31]. As a control for specific import into mitochondria, membrane potential (Δψ) was dissipated prior to the import reaction by the addition of 1 μM valinomycin, 20 μM oligomycin, and 8 μM antimycin A (supplied as AVO mix (1 % (v/v)). All reactions were stopped by addition of 1 % (v/v) AVO. Samples were then placed on ice and treated with 50 μg/ml proteinase K for 10 min. After addition of 2 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) mitochondria were washed with SEM buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE [31]. Imported and processed precursor proteins were monitored by digital autoradiography of vacuum-dried electrophoresis gels. All import experiments were reproduced at least two times and with at least two independent cell clones.

Results

Genomic analysis

WES data from patient 1 was transferred to BHCMG and re-analyzed for SNVs in genes not presently associated with human disease in an attempt to determine the molecular underpinnings of the phenotype. Potentially pathogenic compound heterozygous variants (p.L582R/p.L71Q) were identified in MIPEP; given what is known about the biology of MIP, this was further pursued as the best potential candidate gene. No other candidate genes with variants bioinformatically predicted to be damaging and conveying a similarly matching phenotype were identified. Upon exchange of our data with the clinical exome laboratory, we identified two more patients with variants in MIPEP who both coincidentally had a similar phenotype; patient 2 was found to have compound heterozygous variants (p.E602*/p.L306F) and patient 3 had a homozygous variant (p.K343E). We next submitted MIPEP to the GeneMatcher tool, a part of the Matchmaker Exchange project (https://genematcher.org) [32, 33], and successfully matched one other patient with a paternally inherited MIPEP SNV (p.H512D) and maternally inherited 1.4-Mb deletion copy number variant (CNV) encompassing the entire gene. Sanger sequencing in the probands and family members confirmed the variants’ presence and their biallelic nature in the probands (Fig. 2). Due to the lack of availability of parental DNA for patient 3, Sanger sequencing of the homozygous variant (p.K343E) was followed by digital droplet PCR to confirm that the variant was indeed homozygous (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

In total, we identified four individuals from four unrelated families with one homozygous and three compound heterozygous variants in MIPEP ( 1). Given that patient 1 with LVNC and cardiomyopathy was initially suspected to have a mitochondrial disorder, MIPEP was prioritized to be an excellent candidate gene given its fundamental role in mitochondrial biogenesis. MIPEP is the strongest candidate among screened variants because the nonsynonymous variants in MIPEP are evolutionarily conserved (Fig. 2) and predicted to be deleterious by Mutation Taster, SIFT, PolyPhen2, and CADD (Table 1). Additionally, in our internal Baylor-CMG research database with ~5000 patients, we did not identify any homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in MIPEP in subjects who presented with other phenotypes. We also searched our clinical exome laboratory database, which also included ~5000 clinical exomes, and did not find any other individuals with homozygous and compound heterozygous MIPEP variants. Upon examination of the 1000 Genome Project, exome variant server (of the Exome Sequencing Project), and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) databases, we observed that four out of six variants (p.L582R, p.L71Q, p.E602*, and p.K343E) are novel and two variants (p.L306F and p.H512D) are rare, observed in the ExAC database in the heterozygous state at a frequency of 8.2 × 10−6 and 3.2 × 10−5, respectively. The heterozygous maternal deletion of patient 4 was identified by array comparative genomic hybridization (Affymetrix CytoScan® HD) and encompasses 1.4 Mb at 13q12 (chr13: 23,519,916–24,941,516, hg19) (Fig. 2; Additional file 3: Figure S3).

Clinical spectrum

Retrospective clinical analyses delineated a consistent phenotype of cardiomyopathy, LVNC, seizures, and hypotonia/developmental delay in all subjects with infantile or early childhood death. Patient 1 was born full term by vaginal delivery after an uncomplicated pregnancy. By 5 months of age, he presented with failure to thrive. At 5.5 months of age, he was diagnosed with LVNC and ECG showed Wolf–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome. His family history is notable for a paternal uncle with a history of supra-ventricular tachycardia and maternal great-aunt with early myocardial infarction (29 years of age) but was otherwise unremarkable. His father’s family is of Scottish/Mexican/Native American ancestry and mother’s family is of Colombian/Native American ancestry. There is no known consanguinity. Physical examination revealed length, weight, and head circumference below the fifth centile and he had a wide mouth and bulbous nasal tip, demonstrated tongue-thrusting, and was hypotonic with head lag. Brain MRI showed microcephaly with prominent extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces. Evaluations revealed an anion gap metabolic acidosis (anion gap = 25; reference range 3–11 mEq/L) with lactate of 3.2 mmol/L (reference range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L). Plasma amino acid analysis revealed slightly elevated alanine of 553 μmol/L (reference range 103–528 μmol/L) but was otherwise unremarkable. Skeletal muscle biopsy showed evidence for mitochondrial proliferation and lipid droplets by electron microscopy (Table 1). Electron transport chain (ETC) analysis of muscle at a CLIA-certified laboratory showed reductions in several respiratory chain complex activities, although not sufficiently low to satisfy a minor criterion of the modified Walker criteria for the diagnosis of a respiratory chain disorder (Additional file 4: Table S1) [34]. His hypotonia evolved into hypertonia and he has continuous abnormal movements and dystonic posturing. His EEG was normal. He also developed multiple gastrointestinal symptoms, including intermittent vomiting and constipation. He is alive at 4.5 years of age.

Patient 2 was a product of full-term gestation and pregnancy was uncomplicated. A cataract was noted in the left eye shortly after birth and was removed at 3 months of age. She was irritable and fed poorly in the first months of life and had an upper endoscopy at 9 months of age that revealed eosinophilic esophagitis. At 11 months of age she presented with poor feeding and fatigue and was diagnosed with LVNC and dilated cardiomyopathy. Family history was significant for an older brother who had cataracts and infantile spasms and died unexpectedly at 14 months of age of unknown cause. Parents are of European ancestry with no known consanguinity. On physical exam, she had significant hypotonia and global developmental delay. Clinical testing for mitochondrial and other genetic disorders was performed throughout her lifetime and failed to identify a cause for LVNC and hypotonia. She was listed for heart transplant and had a Berlin assist device inserted as a bridge to transplant after worsening cardiac ejection fraction. She subsequently developed uncontrollable seizures. The Berlin device was removed and she died at the age of 2 years. An autopsy revealed diffuse neuronal loss with parenchymal rarefaction and cortical/white matter gliosis involving the frontal cortex, ventral forebrain, and pontine tegmentum (likely secondary to poor brain perfusion from heart disease). LVNC with dilated cardiomyopathy was noted and quadriceps muscle biopsy revealed features of metabolic myopathy (Table 1).

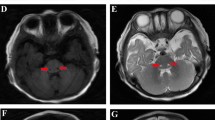

Patient 3 was born at 36 weeks gestation due to pre-term labor. The pregnancy had been uncomplicated. The parents are first-degree cousins from Egypt. There are no similar medical problems in the family. At the age of 2.5 months he had feeding problems with failure to thrive. He was not focusing and exhibited no social smile. At the ages of 5 and 10 months, he was admitted to the hospital for respiratory problems, metabolic acidosis (with lactates of 4.4 and 11.1, respectively; reference range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L) and transient elevation in liver enzymes (alanine transaminase (ALT) 357 U/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 428 U/L; reference range ALT 6–45 U/L, AST 20–60 U/L). At the age of 9 months, echocardiogram revealed left ventricular hypertrophy without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and a small secundum atrial septal defect with left to right shunt. The biventricular function was normal. On physical examination, he was noted to have a long philtrum. There was opisthotonus and severe head lag when pulled to sit. By the age of 10 months he developed microcephaly and seizures. Clinical mitochondrial ETC studies from skin biopsy showed mild reductions in all mitochondrial complexes except for complex II and complex V, which were normal (Additional file 4: Table S1). On brain MRI at 10 months, diffusion-weighted images showed a bilateral and symmetrical increase in signal intensity of the basal ganglia, involving mainly the lentiform nucleus. The periventricular white matter showed hyperintense signal in T2-weighted images, interpreted as either normal myelination processes or changes reflecting neurodegenerative processes or a metabolic disorder. The spectroscopy sample on the basal ganglia showed signs of neuronal loss or degradation. He died at 11 months of age.

Patient 4 was delivered by Cesarean section at 33 weeks gestation due to maternal preeclampsia and fetal decelerations. At birth, he was noted to have significant respiratory depression and was intubated. Seizures began within the first hour of life. Physical examination revealed a gallop rhythm and an echocardiogram demonstrated severe biventricular hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. He had dysmorphic features including deep-set eyes, anteverted nares, depressed nasal bridge, midface hypoplasia, severe micrognathia, facial asymmetry, and an accessory palmar crease on the right hand. He was diagnosed with congenital hyperinsulinemia (blood glucose 20 mg/dL; reference range 70–110 mg/dL) and lactic acidosis (8.9–10.4 mmol/L; reference range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L). Laboratory studies showed significant elevations in alanine, glutamine, and proline that were likely to be consistent with liver disease and lactic acidemia. Urine organic acid analysis showed elevated lactate, pyruvate, ketones, and intermediates of the Krebs cycle consistent with lactic acidosis and ketosis. On day 8 of life he was diagnosed with microcolon. By day 14 of life, he required increased ventilatory support; despite this, blood gases continued to worsen with a persistent lactic acidosis and on day 19 of life he expired. Autopsy demonstrated multiple anomalies including rhombencephalosynapsis, narrow bowel, dilated urinary bladder and ureters, small lungs, and massive thick-walled heart. The ventricles showed thick trabeculae that spanned the lumen and thick walls with underlying non-compaction and focal clefts. Additional cardiac findings included patent ductus arteriosus, small membranous ventricular septal defect, congestive heart failure, and pericardial edema. Light and electron microscopic findings of skeletal muscle (diaphragm) and cardiac muscle showed numerous lipid droplets, glycogen deposition (especially cardiac muscle), and large aggregates of mitochondria with bloated vesicular cristae (Table 1). Family history is significant for a previous female infant that presented with cardiomyopathy in the immediate postnatal period and subsequently expired by 16 days of life; it is unknown if she had LVNC or other features such as hypotonia and cataracts.

Functional analyses

MIP and its yeast homologue Oct1 are highly conserved (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Therefore, we employed a yeast model system to assess the effects of the disease mutations on MIP in vivo. We introduced the Oct1 mutations by site-directed mutagenesis and expressed the wild type and disease mutants from a plasmid under the endogenous promoter in an OCT1 deletion strain [12]. Mitochondria were isolated and analyzed for Oct1 processing defects by SDS-PAGE and immunodecoration (Fig. 3a). Re-expression of the wild-type Oct1 protein rescued the processing defect of the Oct1 substrates Mdh1 and Sdh4 (Fig. 3a, lanes 1 and 4) while yeast cells transformed with the empty vector (e.v.) as control showed complete accumulation of Oct1 processing intermediates (Fig. 3a, lanes 2 and 5). Mutation of Oct1 at position L83Q (MIP L71Q) also fully abolished Oct1 processing (Fig. 3a, lane 3). Immunodecoration using an antibody specific to Oct1 revealed that expression of the L83Q mutant does not result in detectable Oct1 protein levels in mitochondria. Consequently, the L83Q mutant mimics an OCT1 deletion phenotype. Mutations of L339F (MIP L306F, Fig. 3a, lane 6) and K376E (MIP K343E, Fig. 3a, lane 7) showed increased accumulation of Oct1 processing intermediates for Mdh1 and Sdh4, indicating an impaired Oct1 proteolytic function in these mutants in vivo. In contrast, non-Oct1 substrates (controls) were not changed and the protein levels of these two Oct1 mutants were comparable to those of the wild type.

In vivo analysis of MIPEP-derived SNVs in the homologous Oct1 protein from S. cerevisiae. a Immunoblot analysis of mitochondria isolated from oct1Δ yeast cells transformed with plasmids encoding wild-type Oct1 (Oct1 WT) or Oct1 mutants (L83Q, L339F, K376E) under the endogenous promoter or the empty control plasmid (e.v.). Cells were grown at 24 °C on a fermentable carbon source prior to organelle isolation. b Growth of yeast strains expressing Oct1WT or mutants Oct1L339F and Oct1K376E. Plasmid shuffling generated strains and growth behavior assessed on fermentative and respiratory carbon sources at low (23 °C) and high (37–38 °C) temperature. c Immunodecoration of mitochondria isolated from strains shown in b after cell growth for 10 h at 37 °C under respiratory conditions (non-fermentable carbon source). i processing intermediate, m mature protein, p precursor

Deletion of Oct1 in yeast results in loss of mitochondrial DNA. As a consequence OCT1 deletion strains are not viable on non-fermentable carbon sources (where mitochondrial respiration is essential for cell viability). Several of the known Oct1 substrates, e.g., Rip1 and Cox4, are subunits of the respiratory chain complexes or the mitochondrial ribosome, e.g., Mrp21, and are, therefore, required for survival under respiratory growth conditions. In order to analyze the effect of the Oct1 mutants under respiratory conditions, we generated yeast cells expressing the various Oct1 mutants by plasmid shuffling (see “Methods” for details). The approach yielded viable strains for the L83Q, L339F, and K376E Oct1 mutants. (However, due to the lack of Oct1 in the mitochondria of the L83Q strain, growth under respiratory growth assessment was not possible.) While both Oct1 L339F and K376E expressing strains showed no growth defect on fermentative carbon sources, both strains displayed a severe growth defect under respiratory conditions at higher temperature (Fig. 3b). We isolated mitochondria from these strains after growth at a non-permissive temperature for 10 h and analyzed the protein steady state levels by SDS-PAGE and immunodecoration (Fig. 3c). In both mutants we found strong accumulation of the processing intermediates of Mdh1, Sdh4, Cox4, Mdj1, Prx1, and Rip1, revealing a severe decrease of Oct1 activity. The processing defect was most pronounced in the K376E mutant, in which the mature form of Rip1 was virtually absent. Control proteins, which are not substrates of Oct1, were not affected. Taken together, the analyses of the Oct1 mutations in vivo under respiratory conditions demonstrate a strong accumulation of processing intermediates of Oct1 substrates inside mitochondria, indicating a decreased proteolytic activity of Oct1.

In order to directly analyze Oct1 activity in the mutant strains in vitro, we generated [35S]radiolabeled precursor proteins of the Oct1 substrates Mdh1, Cox4, and Mrp21 by in vitro transcription/translation and imported them into isolated mitochondria. Samples were separated via SDS-PAGE and the different precursor processing steps were monitored by autoradiography [12, 31]. For all three precursor proteins the Oct1-mediated processing of the intermediate (i) forms to the mature (m) protein was severely impaired (Fig. 4a-c). Strikingly, the more affected Oct1 processing activity in the K376E mutant mitochondria correlated with the stronger accumulation of precursor intermediates in the mutant cells in vivo (Fig. 3c). Processing of the Atp2 precursor, which is cleaved by MPP but not Oct1, was not affected (Fig. 4d). Thus, our approach revealed that both mutations L339F and K376E diminish the proteolytic activity of Oct1 not only in vivo but also in a direct in organello processing assay.

In organello processing activity of Oct1L339F and Oct1K376E mutants. a–c In vitro import and processing of radiolabeled Mdh1, Cox4, and Mrp21 preproteins in isolated mitochondria (Mito.) from indicated mutant strains compared to wild type (Oct1 WT). d In vitro import and processing of the Oct1-independent preprotein Atp2. The reaction was performed as in a–c. Δψ is the mitochondrial membrane potential. i processing intermediate, m mature protein, p precursor

Discussion

The application of WES in clinical practice has led to the identification of novel Mendelian disorders [26, 35, 36]. We have identified four individuals with rare biallelic variants in MIPEP who presented with a syndrome of LVNC, DD, seizures, hypotonia, cataracts, and infantile death. Three out of four patients (75 %) have passed away in the first 3 years of life. This demonstrates the association between pathogenic biallelic variants in MIPEP and LVNC and early childhood death [37].

Mitochondrial presequence proteases are essential to maintain a functional mitochondrion. The majority of imported mitochondrial preproteins carry N-terminal presequences as targeting signals and require proteolytic cleavage by presequence proteases. While some mitochondrial proteins only require one step of presequence cleavage by MPP, approximately 25 % of proteins with the N-terminal targeting sequence require a second step of cleavage by MIP or XPNPEP3/Icp55. In this 25 %, the MPP processing intermediates carry destabilizing N-terminal amino acids and are subject to rapid degradation [12, 14, 15]; removal of an additional octapeptide by Oct1 or a single amino acid by XPNPEP3/Icp55 reveals stabilizing N-terminal residues following a mitochondrial N-end rule [12, 14, 16, 38]. The proteolytic action of Oct1 and XPNPEP3/Icp55 is required, therefore, to maintain a stable mitochondrial proteome (Fig. 1).

Functional analysis of the Oct1 L306F/L339F and K343E/K376E mutants revealed a severe decrease in Oct1 processing activity, as demonstrated by accumulation of processing intermediates. These processing intermediates included subunits of ETC complexes Sdh4 (succinate dehydrogenase, subunit of respiratory chain complex II and a novel Oct1 substrate), Rip1 (Rieske iron-sulfur-protein, subunit of respiratory chain complex III), Cox4 (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 4 of respiratory chain complex IV), the citrate cycle enzyme Mdh1 (mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase), the ribosomal subunit Mrp21, the peroxiredoxin Prx1, and the mtHsp70 co-chaperone Mdj1 (also a novel Oct1 substrate) (Figs. 3 and 4), which showed strong accumulation in strains expressing the mutant versions of Oct1 (L339F and K376E). Since most of these proteins either directly or indirectly influence mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, it is highly likely that MIP/Oct1 defects affect mitochondrial bioenergetics. Therefore, defects in Oct1 activity might impact on respiratory chain activity.

Analysis of the protein levels of the Oct1 mutant L83Q revealed that the protein was not detectable in isolated mitochondria; the Oct1 L83Q mutant consistently mimicked an OCT1 deletion phenotype (Fig. 3). This could be caused by decreased import rates or rapid turnover of the mutant protein upon synthesis or translocation into mitochondria.

Our functional data are analogous to the previous experiments in yeast illuminating the consequences of loss of Oct1 activity. Previously it has been demonstrated that the deletion of the yeast homolog of MIPEP, Oct1, disrupted iron-sulfur (FeS), Cox4, and ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) protein maturation. Conversely, the reintroduction of Oct1 into the yeast led to the resumption of FeS, Cox4, and OTC protein processing [39]. Furthermore, the biochemical and metabolic consequences of Oct1 deletion include a significant reduction in NADH dehydrogenase activity and succinate dehydrogenase activity that has been explained by a partial loss of mitochondrial respiratory component function [39]. Subsequent experiments in a yeast experimental model revealed other functions of Oct1, including its role in processing of mitochondrial proteins involved in regulation of mtDNA replication [39, 40]. The biochemical evaluations of Oct1 in yeast have shed light on its protein structure, revealing a zinc-binding domain involved in its cleavage activity. Mutations in the zinc-binding domain disrupt the Oct1 catalytic activity; four mutations in the zinc-binding domain, including p.H558R, p.E559D, p.H565R, and p.E587D, caused global loss of Oct1 activity in yeast [41].

Recessive mutations in XPNPEP3 (MIM 613159) have been reported to cause nephronophthisis-like nephropathy 1 (NPHPL1) [42]. Mutations in the alpha subunit of MPP, encoded by PMPCA (MIM 213200), have been recently identified to cause an autosomal recessive form of non-progressive cerebellar ataxia [43]. Copy number variations and SNVs have been reported to alter the inner mitochondrial membrane peptidase subunit 2 encoded by IMMP2L, causing neurodevelopmental disorders and age-associated neurodegeneration, respectively [44, 45]. Our identification of pathogenic variants in MIPEP in patients with LVNC and neurologic abnormalities illustrates the fundamental role of presequence proteases in mitochondrial protein processing and function and their contribution to human disease.

Conclusions

Our study reveals the first link between SNVs in the gene of the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase MIPEP and severe forms of LVNC. Phenotypic evaluation following the identification of biallelic MIPEP variants in four patients identified a shared and rare syndrome of LVNC, DD, seizures, hypotonia, cataracts, and infantile/early childhood death. Experimental data in yeast support the pathogenicity of these variants and indicates that the mechanism of action is loss of function of MIP. The identification and description of the patients’ genotype and phenotype together with functional biochemical analysis provide insights into the consequences of MIP dysfunction. Identification of this severe, early-onset condition expands the phenotypic spectrum associated with loss of mitochondrial presequence protease function to include cardiomyopathy and neurologic impairment.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- BHCMG:

-

Baylor Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics

- CNV:

-

Copy number variant

- DD:

-

Developmental delay

- ETC:

-

electron transport chain

- ExAC:

-

Exome Aggregation Consortium

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- LVNC:

-

Left ventricular non-compaction

- MIM:

-

Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- MIP:

-

Mitochondrial intermediate peptidase

- MPP:

-

Mitochondrial processing peptidase

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

Towbin JA, Lorts A, Jefferies JL. Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61282-4.

Ichida F, Hamamichi Y, Miyawaki T, Ono Y, Kamiya T, Akagi T, Hamada H, Hirose O, Isobe T, Yamada K, et al. Clinical features of isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium: long-term clinical course, hemodynamic properties, and genetic background. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(1):233–40.

Klaassen S, Probst S, Oechslin E, Gerull B, Krings G, Schuler P, Greutmann M, Hurlimann D, Yegitbasi M, Pons L, et al. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes in left ventricular noncompaction. Circulation. 2008;117(22):2893–901.

Probst S, Oechslin E, Schuler P, Greutmann M, Boye P, Knirsch W, Berger F, Thierfelder L, Jenni R, Klaassen S. Sarcomere gene mutations in isolated left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy do not predict clinical phenotype. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4(4):367–74.

Monserrat L, Hermida-Prieto M, Fernandez X, Rodriguez I, Dumont C, Cazon L, Cuesta MG, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Peteiro J, Alvarez N, et al. Mutation in the alpha-cardiac actin gene associated with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular non-compaction, and septal defects. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(16):1953–61.

Luedde M, Ehlermann P, Weichenhan D, Will R, Zeller R, Rupp S, Muller A, Steen H, Ivandic BT, Ulmer HE, et al. Severe familial left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy due to a novel troponin T (TNNT2) mutation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86(3):452–60.

Ichida F, Tsubata S, Bowles KR, Haneda N, Uese K, Miyawaki T, Dreyer WJ, Messina J, Li H, Bowles NE, et al. Novel gene mutations in patients with left ventricular noncompaction or Barth syndrome. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1256–63.

Vatta M, Mohapatra B, Jimenez S, Sanchez X, Faulkner G, Perles Z, Sinagra G, Lin JH, Vu TM, Zhou Q, et al. Mutations in Cypher/ZASP in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(11):2014–27.

Luxan G, Casanova JC, Martinez-Poveda B, Prados B, D'Amato G, MacGrogan D, Gonzalez-Rajal A, Dobarro D, Torroja C, Martinez F, et al. Mutations in the NOTCH pathway regulator MIB1 cause left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):193–201.

Bione S, D’Adamo P, Maestrini E, Gedeon AK, Bolhuis PA, Toniolo D. A novel X-linked gene, G4.5. is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12(4):385–9.

Gakh O, Cavadini P, Isaya G. Mitochondrial processing peptidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592(1):63–77.

Vogtle FN, Prinz C, Kellermann J, Lottspeich F, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Mitochondrial protein turnover: role of the precursor intermediate peptidase Oct1 in protein stabilization. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(13):2135–43.

Teixeira PF, Glaser E. Processing peptidases in mitochondria and chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(2):360–70.

Vogtle FN, Wortelkamp S, Zahedi RP, Becker D, Leidhold C, Gevaert K, Kellermann J, Voos W, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, et al. Global analysis of the mitochondrial N-proteome identifies a processing peptidase critical for protein stability. Cell. 2009;139(2):428–39.

Burkhart JM, Taskin AA, Zahedi RP, Vogtle FN. Quantitative profiling for substrates of the mitochondrial presequence processing protease reveals a set of nonsubstrate proteins increased upon proteotoxic stress. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(11):4550–63.

Huang S, Nelson CJ, Li L, Taylor NL, Stroher E, Peteriet J, Millar AH. INTERMEDIATE CLEAVAGE PEPTIDASE55 modifies enzyme amino termini and alters protein stability in arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(2):415–27.

Kato A, Sugiura N, Saruta Y, Hosoiri T, Yasue H, Hirose S. Targeting of endopeptidase 24.16 to different subcellular compartments by alternative promoter usage. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(24):15313–22.

Rawlings ND, Tolle DP, Barrett AJ. Evolutionary families of peptidase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2004;378(Pt 3):705–16.

Chew A, Buck EA, Peretz S, Sirugo G, Rinaldo P, Isaya G. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment of the human mitochondrial intermediate peptidase gene (MIPEP). Genomics. 1997;40(3):493–6.

Chew A, Sirugo G, Alsobrook 2nd JP, Isaya G. Functional and genomic analysis of the human mitochondrial intermediate peptidase, a putative protein partner of frataxin. Genomics. 2000;65(2):104–12.

Meyers DE, Basha HI, Koenig MK. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40(4):385–94.

Kisanuki YY, Gruis KL, Smith TL, Brown DL. Late-onset mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes with bitemporal lesions. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(8):1200–1.

Superti-Furga A, Schoenle E, Tuchschmid P, Caduff R, Sabato V, DeMattia D, Gitzelmann R, Steinmann B. Pearson bone marrow-pancreas syndrome with insulin-dependent diabetes, progressive renal tubulopathy, organic aciduria and elevated fetal haemoglobin caused by deletion and duplication of mitochondrial DNA. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152(1):44–50.

Liu S, Bai Y, Huang J, Zhao H, Zhang X, Hu S, Wei Y. Do mitochondria contribute to left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy? New findings from myocardium of patients with left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(1):100–6.

Tang S, Batra A, Zhang Y, Ebenroth ES, Huang T. Left ventricular noncompaction is associated with mutations in the mitochondrial genome. Mitochondrion. 2010;10(4):350–7.

Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, Bainbridge MN, Willis A, Ward PA, Braxton A, Beuten J, Xia F, Niu Z, et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1502–11.

Bainbridge MN, Wang M, Wu Y, Newsham I, Muzny DM, Jefferies JL, Albert TJ, Burgess DL, Gibbs RA. Targeted enrichment beyond the consensus coding DNA sequence exome reveals exons with higher variant densities. Genome Biol. 2011;12(7):R68.

Reid JG, Carroll A, Veeraraghavan N, Dahdouli M, Sundquist A, English A, Bainbridge M, White S, Salerno W, Buhay C, et al. Launching genomics into the cloud: deployment of Mercury, a next generation sequence analysis pipeline. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:30.

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–303.

Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, Jackson AR, Paithankar S, Coarfa C, Milosavljevic A, Gibbs RA, Yu F. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:8.

Meisinger C, Pfanner N, Truscott KN. Isolation of yeast mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;313:33–9.

Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(10):928–30.

Philippakis AA, Azzariti DR, Beltran S, Brookes AJ, Brownstein CA, Brudno M, Brunner HG, Buske OJ, Carey K, Doll C, et al. The Matchmaker Exchange: a platform for rare disease gene discovery. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(10):915–21.

Bernier FP, Boneh A, Dennett X, Chow CW, Cleary MA, Thorburn DR. Diagnostic criteria for respiratory chain disorders in adults and children. Neurology. 2002;59(9):1406–11.

Yang Y, Muzny DM, Xia F, Niu Z, Person R, Ding Y, Ward P, Braxton A, Wang M, Buhay C, et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1870–9.

Bainbridge MN, Wiszniewski W, Murdock DR, Friedman J, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Newsham I, Reid JG, Fink JK, Morgan MB, Gingras MC, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for optimized patient management. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(87):87re83.

Stevenson DA, Carey JC. Contribution of malformations and genetic disorders to mortality in a children's hospital. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;126A(4):393–7.

Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway and regulation by proteolysis. Protein Sci. 2011;20(8):1298–345.

Isaya G, Miklos D, Rollins RA. MIP1, a new yeast gene homologous to the rat mitochondrial intermediate peptidase gene, is required for oxidative metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(8):5603–16.

Branda SS, Isaya G. Prediction and identification of new natural substrates of the yeast mitochondrial intermediate peptidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(45):27366–73.

Chew A, Rollins RA, Sakati WR, Isaya G. Mutations in a putative zinc-binding domain inactivate the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226(3):822–9.

O’Toole JF, Liu Y, Davis EE, Westlake CJ, Attanasio M, Otto EA, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Becker C, Nuutinen M, et al. Individuals with mutations in XPNPEP3, which encodes a mitochondrial protein, develop a nephronophthisis-like nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(3):791–802.

Jobling RK, Assoum M, Gakh O, Blaser S, Raiman JA, Mignot C, Roze E, Durr A, Brice A, Levy N, et al. PMPCA mutations cause abnormal mitochondrial protein processing in patients with non-progressive cerebellar ataxia. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 6):1505–17.

Gimelli S, Capra V, Di Rocco M, Leoni M, Mirabelli-Badenier M, Schiaffino MC, Fiorio P, Cuoco C, Gimelli G, Tassano E. Interstitial 7q31.1 copy number variations disrupting IMMP2L gene are associated with a wide spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol Cytogenet. 2014;7:54.

Liu C, Li X, Lu B. The Immp2l mutation causes age-dependent degeneration of cerebellar granule neurons prevented by antioxidant treatment. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):167–76.

Acknowledgements

We thank the family members, clinicians, Nijmegen Center for Mitochondrial Disorders (NCMD) and Dr Grazia Isaya, MD, PhD from Mayo clinic for their assistance and advice in this study. We thank Dr Chris Grant for Prx1 antiserum.

Funding

CM was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and FNV by the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung and the Emmy-Noether-Program (DFG). W-LC is supported by CPRIT training program RP140102. This work was supported in part by the US National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant number U54HG006542 to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (BH-CMG). LCB was supported by NIH T32 GM07526.

Availability of data and materials

All reported disease associated variants in MIPEP have been deposited into ClinVar under accession numbers SCV000223996 through SCV000224002 in agreement with IRB approval and patient consent. The ClinVar entries will be publicly released after publication.

Authors’ contributions

MKE, ZCA, FNV, JRL, CM, and VRS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. FNV and PM performed the functional analysis of Oct1 mutants. VRS and JRL organized phenotype assessment and supervised the study. WLC, JAR, RM, TG, SNJ, DMM, XW, SG, PVR, LJW, EB, RAG, CME, JRL, RJR, OAA, YY, FX, MCW, and CM generated and advised on data analysis. LCB, AAS, SP, HHZ, SRL, JH, RJR, and OAA identified and collected patients. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) and Miraca Holdings Inc. have formed a joint venture with shared ownership and governance of the Baylor Genetics Laboratories, which performs clinical exome sequencing. VRS, JAR, FX, MW, CME, SEP, YY, RAG, and JRL are employees of BCM and derive support through a professional services agreement with the Baylor Genetics Laboratories. SEP and JRL serve on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Baylor Genetics Laboratories. RAG serves as interim Chief Scientific Officer of the Baylor Genetics Laboratories. JAR reports personal fees from Signature Genomic Laboratories, PerkinElmer, Inc., in the past 36 months. RAG reports consulting fees from GE-Clarient. JRL has stock ownership in 23andMe, is a paid consultant for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, has stock options in Lasergen, Inc., and is a coinventor of US and European patents related to molecular diagnostics for inherited neuropathies, eye diseases, and bacterial genomic fingerprinting. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

A written consent was obtained to publish the details of all patients from the parents/legal guardians.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine IRB (protocol H-29697). The Baylor College of Medicine IRB (IORG number 0000055) is recognized by the United States Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the federal wide assurance program. The Baylor College of Medicine IRB is also fully accredited by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP). For individuals who were alive at the time the research began, written informed consent was obtained from them or their legally authorized representative/parent. For those who were deceased at the time of the initiation of the study (and where existing specimens or data were utilized in our analysis), parents were notified of the study and agreed verbally to the study. Under United States federal regulations, it is impossible to obtain consent for a deceased individual.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Sequence alignment of human and yeast MIP. (JPG 890 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) was performed using the QX200™ AutoDG™ Droplet Digital™ PCR System from Bio-Rad following the manufacture’s protocols. Briefly, a 20-μL mixture was set up for each PCR reaction, containing 10 μL of 2× Q200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix, 0.25 μL of KpnI restriction enzyme (NEB, catalog number R0142S), 0.25 μL of each primer (10 μM) and 20 or 40 ng of genomic DNA. Reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for an hour for enzymatic digestion, following by automatic droplet generation, PCR reaction, and droplet reading. Cycling conditions for PCR were: 5 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C/1 min at 60 °C/2 min at 72 °C, 5 min at 4 °C, 5 min at 90 °C, and finally infinite hold at 4 °C. Ramp rate was set for 2 °C per second for all steps. Data were analyzed using QuantaSoftTM Software from Bio-Rad and concentrations of positive droplets (number of positive droplets per microliter of reaction) were obtained for each PCR reaction. Raw data of ddPCR and primer sequences are shown. A primer pair targeting MIPEP around chr13: 24436467 and two control primer pairs targeting copy number-neutral regions were used to perform ddPCR in the proband. Absolute positive droplet concentrations (copies/μL) are plotted from ddPCR results of the three primer pairs. Similar positive droplet concentrations were observed from ddPCR performed using primers targeting MIPEP and the two control primer pairs for both 20 ng genomic DNA input (around 40 copies/μL) and 40 ng genomic DNA input (around 80 copies/μL). This indicates that there was no copy number difference comparing MIPEP around chr13: 24436467 to the copy number-neutral control regions; therefore, no deletion was detected. Corresponding raw data of ddPCR and primer sequences are shown in (Figure S2). Ctrl control. (JPG 471 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Maternally inherited 1.4-Mb CNV deletion in patient 4 and known genes within the deleted interval. (JPG 883 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S1.

Summary for clinical testing of mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) results in patients with MIPEP variants. NA not applicable, SD standard deviation. (JPG 852 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Eldomery, M.K., Akdemir, Z.C., Vögtle, FN. et al. MIPEP recessive variants cause a syndrome of left ventricular non-compaction, hypotonia, and infantile death. Genome Med 8, 106 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-016-0360-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-016-0360-6