Abstract

Background

Malaria vector control has been implemented chiefly through indoor interventions targeting primary vectors resulting in population declines—pointing to a possible greater proportional contribution to transmission by secondary malaria vectors with their predominant exophagic and exophilic traits. With a historical focus on primary vectors, there is paucity of data on secondary malaria vectors in many countries in Africa. This study sought to determine the species compositions and bionomic traits, including proportions infected with Plasmodium falciparum and phenotypic insecticide resistance, of secondary vectors in three sites with high malaria transmission in Kisumu County, western Kenya.

Methods

Cross-sectional sampling of adult Anopheles was conducted using indoor and outdoor CDC light traps (CDC-LT) and animal-baited traps (ABTs) in Kakola-Ombaka and Kisian, while larvae were sampled in Ahero. Secondary vectors captured were exposed to permethrin using WHO bioassays and then analyzed by ELISA to test for proportions infected with P. falciparum sporozoites. All Anopheles were identified to species using morphological keys with a subset being molecularly identified using ITS2 and CO1 sequencing for species identification.

Results

Two morphologically identified secondary vectors captured—An. coustani and An. pharoensis—were determined to consist of four species molecularly. These included An. christyi, An. sp. 15 BSL-2014, an unidentified member of the An. coustani complex (An. cf. coustani) and a species similar to that of An. pharoensis and An. squamosus (An. cf. pharoensis). Standardized (Anopheles per trap per night) capture rates demonstrate higher proportions of secondary vectors across most trapping methods—with overall indoor and outdoor CDC-LTs and ABT captures composed of 52.2% (n = 93), 78.9% (n = 221) and 58.1% (n = 573) secondary vectors respectively. Secondary vectors were primarily caught outdoors. The overall proportion of secondary vectors with P. falciparum sporozoite was 0.63% (n = 5), with the unidentified species An. cf. pharoensis, determined to carry Plasmodium. Overall secondary vectors were susceptible to permethrin with a > 99% mortality rate.

Conclusions

Given their high densities, endophily equivalent to primary vectors, higher exophily and Plasmodium-positive proportions, secondary vectors may contribute substantially to malaria transmission. Unidentified species demonstrate the need for further morphological and molecular identification studies towards further characterization. Continued monitoring is essential for understanding their temporal contributions to transmission, the possible elevation of some to primary vectors and the development of insecticide resistance.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria continues to be a burden in the sub-Saharan African region. The World Health Organization (WHO) African region recorded an estimated 215 million malaria cases and 384,000 deaths in 2019, accounting for 94% of the global burden [1]. Approximately 75% of the population in Kenya is at risk of the disease and 16% of outpatient consultations are malaria related [2]. Disease transmission in the country is variable with regions being endemic, epidemic-prone, seasonal transmission, or low risk zones, with prevalence rates of Plasmodium falciparum as high as 36.5% in parts of western Kenya [2, 3].

Primary vectors, described based on their abundance and quantifiable sporozoite rates, are those that are major drivers of malaria incidence [4, 5]. Primary malaria vectors in sub-Saharan Africa are predominantly anthropophilic and anthropophagic (prefer human habitation and biting humans) [4], endophilic (indoor resting) and endophagic (indoor biting) [6]. Consequently, indoor interventions such as Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) and Long-Lasting Insecticide-Treated Nets (LLINs) are most effective against these primary vectors [7] as their behaviors overlap with where and how these interventions function.

Primary malaria vectors documented in western Kenya include An. gambiae (s.s.), An. arabiensis and An. funestus [8]. These vectors are found across Kenya with An. merus also being documented as a significant contributor to transmission in specific areas [9, 10]. Degefa et al. [7] demonstrated that from 2015 to 2016, 71.4% and 12.3% of Anopheles collected in western Kenya using multiple sampling methods were An. gambiae (s.l.) and An. funestus, respectively. Molecular analysis demonstrated that the majority of An. gambiae (s.l.) in Ahero were composed of An. arabiensis (98.9%) while those in nearby Iguhu were 13% with the rest being An. gambiae (s.s.). In Ahero, Kisumu County, An. gambiae (s.s.) sampled from indoor and outdoor CDC light traps had sporozoite rates of 0.38 and 0.35%, respectively, while An. arabiensis had a sporozoite rate of 0.16%. An. funestus collected from indoor CDC light traps and pyrethroid spray catches (PSCs) had sporozoite rates of 2.6 and 2.0%, respectively, suggesting a primary vector status.

Secondary vectors across Africa include species such as An. coustani, An. ziemanni, An. pharoensis, An. rivulorum and An. squamosus [11, 12]. Secondary vectors are those that have historically been documented as playing a minor role—contributing to an estimated 5% of malaria transmission across Africa [5]. Documented secondary malaria vectors in Ahero, Western Kenya, include An. coustani and An. pharoensis with circumsporozoite (CS) protein found in An. coustani specimens demonstrating the ability to transmit malaria [9]. Anopheles ziemanni (part of the An. coustani group) has also been demonstrated to be infectious with malaria in Cameroun and Rwanda [13, 14]. Since the An. coustani group consists of several documented species, and morphological identifications are usually used when characterizing vectors, there remains the possibility of other complex members as well as novel species being vectors from this complex [15]. Studies have documented that An. pharoensis is a vector in other parts of Kenya as well as Tanzania [7, 16]. Approximately 15.7% of the total Anopheles mosquitos collected in Mwea rice fields in Central Kenya were found to be this species with Plasmodium infection rates as high as 1.3% by ELISA [17]. Vectors documented with sporozoites in Zambia include An. theileri, An. coustani and An. rivulorum [18].

Most secondary vectors have historically demonstrated a preference for biting and resting outdoors [5, 15] with associated zoophily and zoophagy and may sustain malaria transmission outside the protection of indoor interventions [2, 19,20,21]. Though believed to be of insignificant status in malaria transmission due to their presumed zoophilic behavior, the An. coustani complex and An. squamosus have been documented to be significantly anthropophilic in Zambia—suggesting a possible greater contribution to malaria transmission [11]. In western Kenya studies have also pointed to endophily in members of the An. coustani complex [22].

Several non-primary Anopheles species have been documented in the western Kenya highlands including several novel species [7]. Known species include An. pretoriensis An. maculipalpis, An. coustani, An. theileri, An. rufipes, An. leesoni, An. christyi and An. squamosus [23]. Molecular analysis using the internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) and cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) loci demonstrated the presence of novel and unknown species across multiple geographies [15, 18, 23,24,25]. The lack of molecular data that may distinguish species along with the reliance on historical morphological keys may overlook the presence and contributions of some species to malaria transmission.

The use of indoor-based LLINs and IRS has resulted in a significant decrease in malaria [26, 27]. Three primary selective impacts an intervention may have on vector populations include changes in vector species, changes in vector behaviors and the development and spread of insecticide resistance. Since LLINs and IRS target endophilic and endophagic vectors, primary effects would be seen on primary vectors that demonstrate the susceptible traits of endophagy and endophily. Studies have demonstrated that interventions may result in temporal changes in species composition with associated shifts in primary vector densities [28,29,30]. In western Kenya, extensive LLIN use resulted in relative densities of endophagic and endophilic An. gambiae (s.s.) declining while those of An. arabiensis increased significantly [28]. This change in species compositions may be attributed to LLIN-based mortality impacting the predominantly endophilic and endophagic An. gambiae (s.s.) relative to that of the exophagic and exophilic An. Arabiensis—a paradigm also reflected in other datasets [28, 30,31,32]. Changes in behaviors and species compositions following intervention deployment have been demonstrated in several other studies across multiple geographies [6, 19, 24, 26, 33, 34].

The development and spread of insecticide resistance have been associated with intervention implementation. Studies have associated LLIN and IRS with insecticide resistance in several malaria vectors [35,36,37,38,39,40]. For instance, extensive LLIN coverage led to an initial decrease in malaria vector density in western Kenya (Iguhu, Marani and Kombewa) between 2002 and 2007 followed by a 5–10× increase associated with the development of insecticide resistance [35]. Though insecticide resistance has been documented in primary vectors [41,42,43], secondary vectors are either not sampled or tested for characterizing insecticide susceptibility.

The historical focus of data collection and transmission characterization based on ‘primary’ vectors may result in a biased dataset—especially in the context of intervention-based impacts on susceptible primary vectors. There remains a lack of data on species composition, population dynamics, bionomics, insecticide resistance status and infection rates. In addition, the continued use of indoor interventions and consequent selective pressures on primary vectors may have differential impacts on secondary vectors that have different bionomic traits. The exophagic and exophilic nature of many secondary vectors allows them to circumvent the increased mortality associated with indoor interventions, with smaller effects on primary epidemiological drivers of transmission—population size and age structure. This may elevate and enhance transmission as well as undermine current efforts to eliminate malaria since they are often sympatric with primary vectors. As long as secondary vectors are able to sustain residual transmission, unchecked by predominant indoor control mechanism, malaria elimination will continue to be a major challenge. This study seeks to fill this knowledge gap by characterizing the species composition of secondary vectors, their bionomic traits, proportions infected with sporozoites and insecticide resistance frequencies to permethrin in Kisumu County, western Kenya.

Methods

Study site: This study was conducted within three regions in Kisumu County, western Kenya—namely Kisian (00.02464°S, 033.60187°E, altitude 1280–1330 m above sea level [masl]), Ahero (00.17259° S,034.91983° E, altitude 1162–1360 masl) and Kakola-Ombaka (0.2496° S, 34.8790° E, 1142.00 m/3746.72 masl) (Fig. 1). Malaria transmission occurs throughout the year in western Kenya, with peaks corresponding to rainfall in mid-April to July and November to December. It is classified as a lake endemic region with a Plasmodium falciparum prevalence of 20%-50% [3]. Anopheles gambiae (s.s.), An. arabiensis and An. funestus (s.s.) are the historical primary vectors in the region [28, 44, 45]. Secondary vectors include An. rivulorum, An. coustani (s.l.) and An. pharoensis [5, 7, 15]. While Ahero is characterized by large irrigation fields which provide favorable larval sites for malaria vector proliferation, Kisian is known for its cattle farming which provides vectors with a source of bovine blood and brings them into increased contact with humans. Frequent flooding in lowland Kakola-Ombaka predisposes this site to vector proliferation.

Mosquito sampling

To establish the composition and temporal density of secondary malaria vectors, and to determine their susceptibility to the pyrethroid insecticide permethrin, Anopheles mosquitoes were sampled in a cross-sectional study design using CDC light traps (CDC-LTs), animal (cow)-baited tent traps (ABTs) and larval dipping over the rainy season.

Paired indoor and outdoor CDC-LT catches were conducted in Kakola-Ombaka for 14 days per month for 3 months (April to June, 2019), in 20 sentinel houses per night, for a total of 840 indoor and outdoor trapping nights each. With the aim of using houses with larger odor sources, houses with more occupants (> 4 people) were selected. Indoor CDC-LTs were hung 15 cm from occupied beds, while outdoor traps were placed 1 to 2 m from windows and at a height of 4 m from the ground. Sampling started at 1900 h, and the traps were collected at 0500 h.

ABTs, using a 2–3-year-old cow, were conducted in both Kakola-Ombaka and Kisian for 14 days per month for 3 months (April to June 2019) each, using two ABTs per night per site for a total of 84 ABT trapping nights per site. ABTs were placed 3 m from the nearest house.

Larval sampling for insecticide resistance tests were conducted in Ahero for 14 days each month (April to June 2019). Collections were conducted using standard 350-ml dippers between 0900 and 1200 h per day in all identified water bodies, including ponds, swamps, marshes, irrigation water, stagnant drainage ditches and flood plains.

Adult processing

Adult mosquitoes were morphologically identified with the help of a dissecting microscope according to standard taxonomic keys [46] and sorted according to their abdominal status. Each specimen was morphologically identified, assigned a unique code to capture the collected site, house number, date of collection and collection method and stored in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes on silica gel for further processing.

Larval rearing

Collected larvae were labeled by habitat type and transported to the Entomology section, KEMRI-CGHR laboratory, fed with fish food and reared to adulthood using standardized laboratory methods [47]. Adult mosquitoes were fed on a 10% sucrose solution. Temperature was maintained at 27–30 °C and humidity at 80–85%.

WHO insecticide susceptibility assay

Insecticide susceptibility tests were conducted on both adults captured as well as larvae raised to adults. Adults captured (all females) were immediately transported to the laboratory and sugar fed. Insecticide susceptibility tests using 0.75% permethrin-impregnated papers, following standard insecticide susceptibility monitoring guidelines [48], were conducted 3–4 h following capture, irrespective of abdominal (blood-fed) status. Larvae sampled from Ahero were raised to adults in the insectary following standard larval rearing methodologies [47]. Three-day-old adult, non-blood fed females raised from larvae were exposed to 0.75% permethrin-impregnated papers [48]. Anopheles gambiae (Kisumu Strain) permethrin-susceptible mosquitoes were used in paired controls. Negative controls using only carrier oil and susceptible controls were not conducted. For all specimens, knockdown rates were recorded at 10-min intervals for 1 h and mortality recorded 24 h post-exposure. Mosquitoes that remained alive after 24 h of exposure were killed at − 20 °C. All mosquitoes were labeled by assay phenotype (knocked down/alive) and morphologically identified to species before being individually preserved in Eppendorf tubes containing silica gel. Phenotypic insecticide resistance status was determined based on mortality rates according to WHO [48], where mortality rates between 98 and 100% indicated susceptibility, 90–97% suggested possible resistance that needed additional analysis and < 90% indicated resistance.

Mosquito species identification

All adult Anopheles were morphologically identified using a dissecting microscope according to standard taxonomic keys [49]. A subset of morphologically identified secondary vector specimens were sequenced (ABI3730XL, Applied Biosystems, USA) at the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) and/or cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) loci towards species determination [18, 23, 25]. Specimens sequenced were randomly chosen across all adult trapping methods and sites. DNA was extracted from legs and wings. Samples were first sequenced at the ITS2 loci, and then a subset of samples with successful ITS2 sequences were also sequenced at the CO1 loci. Molecular identification was conducted blind to morphological identity to prevent any bias in the analysis. Final species confirmation required high sequence identity (98% or greater) to voucher sequences in multiple databases. CO1 and ITS2 database comparisons for each sample were paired to determine species when either CO1 or ITS2 alone did not produce significant results to voucher sequences. Consensus sequences were manually inspected for insertions, deletions and repeat regions to ensure these sequence differences did not inflate divergence and decrease identity scores [18, 23, 25]. Consensus sequences of each sequence group were compared (BLASTn) to the NCBI nr and BOLD [50] databases to identify species. Molecularly identified An. gambiae (s.l.) samples were identified to species using a PCR diagnostic assay [51].

Sporozoite infection

All female secondary vector specimens were dissected, and the thoraces and heads were analyzed for the presence of circum-sporozoite antigen of P. falciparum using an Enzyme-Linked Immuno-Sorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (MRA-890, MR4, ATCC, Manassas, VA). CS-ELISA-positive malaria vectors were determined using the ELISA kit procedure [52]. All sporozoite-positive mosquitoes were molecularly identified to species as above. The proportion positive for P. falciparum sporozoites was computed as the proportion of vectors ELISA positive for the CS protein out of the total analyzed, with the results presented as infection rates.

Data analysis

Data collected on paper data collection sheets were entered into Microsoft Excel. Phenotypic insecticide resistance status was determined based on mortality rates according to WHO [48]—where mortality rates between 98 and 100% indicated susceptibility, 90%–97% suggested possible resistance with additional analysis required and < 90% indicated resistance. The sporozoite rate was computed as the proportion of vectors positive for circumsporozoite (CS) protein out of the sum total analyzed and the results presented as infection rates.

Ethical clearance

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI). Permission to carry out this study was obtained by the area chiefs and sub-chiefs. Informed consent for sampling of mosquito specimens was obtained from household and field owners.

Results

Multiple collection methods were used over the rainy season to evaluating the species compositions, bionomic traits, proportion positive for P. falciparum sporozoites and insecticide resistance frequency of secondary Anopheles vectors (non-An. gambiae (s.l.) and non-An. funestus) in Kisumu County, western Kenya.

Species composition and bionomics

The overall proportion of adult secondary malaria vectors sampled (61.43%; n = 887) was higher than that of primary vectors (38.57%; n = 557). Morphological identification of adult secondary vectors (n = 887) demonstrated the presence of An. coustani (57.0%, n = 506) and An. pharoensis (42.9%, n = 381) at both sites sampled (Kisian and Kakola-Ombaka) (Table 1).

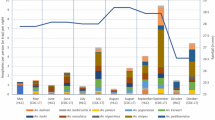

When compared to primary vectors and standardized to collection method (specimens per trap per night), indoor CDC-LTs captured equal numbers of primary and secondary vectors (0.10 and 0.11/trap/night, respectively) and outdoor CDC-LTs captured half the number of primary vectors (0.07 primary and 0.14 secondary/trap/night), while animal-baited traps captured the most primary vectors (2.46/trap/night) with more secondary vectors (3.41/trap/night) (Fig. 2). Overall, CDC-LTs captures were composed of 31.4% (n = 144) primary vectors and 68.5% (n = 314) secondary vectors, while ABT sampling had 41.9% (n = 413) primary vectors and 58.1% (n = 573) secondary vectors. Kisian was the only site with higher primary vectors in the ABT.

Standardized trapping densities demonstrate that indoor CDC-LTs captured almost equal numbers of primary and secondary vectors, outdoor CDC-LTs captured half the number of primary vectors, while animal-baited traps captured the most specimens, with more secondary vectors. Anopheles captured per trap per night are denoted above each bar

Molecular identification of Anopheles species

The random subset of morphologically identified samples was successfully sequenced (n = 83) at the ITS2 and/or CO1 regions for molecular species identification. Five species were identified molecularly (Table 2). Of the specimens morphologically identified as An. pharoensis, two were molecularly identified as An. gambiae (s.l.) and one as An. christyi. A single specimen, also morphologically misidentified as An. pharoensis, had its ITS2 sequence only 76% similar to that of An. coustani (henceforth called An. cf. coustani) and is possibly an unknown member of the An. coustani complex or group. The fourth species identified was An. sp. 15 BSL-2014—a potential member of the An. coustani group [23]—and was consequently identified as An. coustani morphologically. The last species—henceforth called An. cf. pharoensis—was primarily morphologically identified as An. pharoensis and was molecularly determined to be a member of Series Cellia, with an ITS2 sequence that matched that of An. pharoensis, while the CO1 sequence was closest to that of An. squamosus (NCBI) and an unknown species—An. KHH4 [53]. Approximately 77% (n = 64) of morphological identifications matched molecular identifications when including cryptic identifications. Species-specific ITS2 and CO1 sequences may be accessed in GenBank (ITS2: MW578718 to MW578722; CO1: MW555792 to MW555794).

Sporozoite ELISAs

Of 791 mosquitoes tested for the presence of P. falciparum parasites, six tested positive for Plasmodium CS antigen. All six sporozoite-positive samples were identified molecularly for the most accurate species determination (Table 2).

Five positive samples were identified as An. cf. pharoensis. A single specimen of An. arabiensis (confirmed with PCR) [51] was also positive. All Plasmodium-positive secondary vector samples were from Kakola-Ombaka and were from outdoor collections—CDC-LTs (n = 2) as well as ABTs (n = 3). Since only a subset of samples was molecularly identified, species-specific infection rates were not possible. Overall, 5 of 789 (minus two molecularly identified An. arabiensis samples) secondary vectors tested were CS positive pointing to an overall secondary vector infection rate of 0.63%.

Insecticide resistance

Insecticide resistance to permethrin was based on both morphologically identified adults captured as well as on larvae raised to adults (Table 3).

Since each morphologically identified species was composed of multiple (molecularly identified) species, overall adult secondary vector mortality rates were 99.43% (n = 887). Larvae sampled from Ahero that were raised to adults also demonstrated high degrees of mortality (overall 99.10% mortality, n = 219). All adult and larval-raised specimens (whether based on morphological species identification, trap type or site) were classified as being susceptible to permethrin.

Discussion

This study characterized the presence, bionomic traits, P. falciparum infected proportions and insecticide susceptibility status of secondary vector species from Kisian, Ahero and Kakola-Ombaka—sites across Kisumu County, Kenya—with several important outcomes.

Multiple collection methods that took advantage of multiple behaviors (endophily, exophily, anthropophily and zoophily) were used over the rainy season to ensure that as many vectors were sampled as possible. In addition to the primary vectors (An. gambiae (s.l.) and An. funestus), four other Anopheles species were identified molecularly that belonged to both identified species as well as cryptic or species complexes (Table 2). The known species was a single specimen of An. christyi identified by its ITS2 sequence (100% identical to that of An. christyi). Anopheles sp. 15 BSL-2014, identified from both ITS2 (100% identical) and CO1 (99% identical) sequences, represented the majority of the samples sequenced (67.4%), is part of the An. coustani complex and was first detected in the Kenyan highlands. This species is likely a close relative of An. coustani; however, low sequence similarity to Group Coustani sequences in the database (such as An. paludis) and the lack of identifying sequences from species such as An. crypticus and An. caliginosus render further granularity with molecular identification impossible.

Another species, identified from a single specimen, had only partial overlap (76%) with the An. coustani ITS2 sequence, and of this overlap, there was low (79%) similarity. Other much lower similarity scores with this sequence demonstrated similarity to An. pullus and An. yatsushiroensis, part of the Group Coustani sibling—Group Hyrcanus, both part of Series Myzorhynchus. The closer similarity to An. coustani suggests that this unknown species may be part of the An. coustani complex. The majority of specimens of the fourth species demonstrated high similarity (98%) to the ITS2 sequence from An. pharoensis, with CO1 sequences being most similar (97%) to An. squamosus and a novel species An. KHH4 [53]. Anopheles pharoensis is believed to consist of two species—An. argenteolobatus and An. cydippis, based on polytene chromosome banding patterns [54]. However, the lack of An. argenteolobatus and/or An. cydippis ITS2 or CO1 sequences in the reference databases precludes this determination.

A DNA barcoding study [53] utilizing CO1 for species identification revealed the presence of An. KHH4 in Western Kenya with a phylogenetic analysis demonstrating its close relationship with An. squamosus. This is the first time an ITS2 sequence has been paired with this CO1 sequence. These sequences may possibly document one of the two species identified within the taxon An. pharoensis Theobald [54].

Morphological identification techniques have their limitations as seen in this study. Here An. gambiae (s.l.) and An. christyi specimens were misidentified as An. pharoensis and four novel species were identified as two species based on morphological characteristics. The difference seen between molecular and morphological results here points to the lack of data on secondary vectors in western Kenya. Secondary vectors are either not utilized for primary analysis or identified using morphological keys leaving out the possibility of the detection of species complexes and novel species as seen in other studies utilizing molecular methods [18, 23,24,25]. The association of specific species with their bionomic traits—especially those that impact intervention efficacy, such as biting spaces and times and insecticide resistance—are vital when understanding where and when transmission is occurring as well as species-specific impacts of intervention strategies. The use of molecular tools, alongside morphological identifications, as is routinely done for the An. gambiae complex and the An. funestus group, would ensure accurate and precise characterization of malaria vectors when characterizing vector-based transmission systems. It is important to note that the molecular analysis represents only 9.4% (83 of 887) of the adult Anopheles specimens captured here, and a more comprehensive molecular analysis may reveal the presence of other species.

The unlikely morphological misidentification of An. coustani as An. pharoensis could not be resolved because the specimens were used for ELISA and/or DNA extractions. This demonstrates the need to retain voucher specimens especially when unidentifiable specimens are found. These voucher specimens serve as referencing entities, recording and detailing the identity of samples used in a study, and may clarify misidentifications and novel specimens in cases such as this. A single leg or a few scales may be utilized for molecular identification with the morphological integrity retained for any further required data validation. These data may also point to and advocate for additional training in morphological identifications.

Rare, unknown and novel species are common in the Anopheles genus and have been reported across the world [18, 23, 25, 55, 56]. More interestingly, some of these species were found to be susceptible to P. falciparum infection. Undescribed species have previously been reported in the Western region of Kenya with some being infected with sporozoites [8, 23, 57]. Further studies are required to determine their vector status, relationship to other species as well as bionomic characteristics that relate to transmission and intervention efficacy. Climate change and local ecological niches are among the factors that may play a role in the occurrence and spread of these novel species [24]. The ability of these species to harbor Plasmodium parasites suggests their role in malaria transmission and the need for them to be targeted by vector control tools.

This study not only demonstrates the unexpected species composition of secondary vectors but also argues that their ‘secondary’ contributions to transmission may be more than expected. When comparing standardized trapping rates (Table 1) 0.10 and 0.07 primary vectors (An. gambiae (s.l.) and An. funestus (s.l.) together) were caught per trap per night by CDC-LTs indoors and outdoors respectively—pointing to their endophilic nature. However, higher trapping rates—0.11 and 0.26/trap/night indoors and outdoors respectively—of secondary vectors were sampled at the same time pointing to both exophilic behaviors as well as larger possible population sizes. Compared to a study [7] done in western Kenya, this study showed a significant increase in secondary vectors collected. This may be attributed to extensive use of ITNs in the region leading to diminished primary vectors and thus reduced competition for secondary vectors—hence their increased density.

When looking at ABTs, primary vector capture rates were 1.71/ABT/night while that of secondary vectors was 6.08/trap per night in Kakola-Ombaka suggesting both zoophily and greater population sizes. This was however reversed in Kisian with 3.20 primary vectors captured per ABT per night while only 0.73 secondary vectors were sampled per trap per night at the same time. With Kisian having a high density of domestic cattle, data may reflect species-specific compositions of the secondary vector species with some possibly being more attracted to bovines than others. Since only a small proportion of secondary vectors was analyzed molecularly, this could not be clarified. Overall, these comparisons suggest that secondary vector biting rates may be equivalent to those of primary vectors (based on CDC-LT catches) while outdoor biting rates may be significantly more (up to 3.7 × more).

Overall secondary vectors were the majority of the collections composing 68.6% of CDC-LT catches and 58.1% of ABT collections. These results are unexpectedly high when compared to other studies [7, 28, 45]. This may reflect the multiple trapping methods used in this study as well as changes in these vector densities over time – reductions in primary vectors with indoor interventions [28] alongside escalations of secondary vector densities with reduced competition [58, 59].

Sporozoite-positive proportions of 0.63% seen in the secondary vectors sampled indicate a large contribution to transmission since biting rates are possibly equivalent to (indoors) or more than (outdoors) those of primary vectors [9]. All sporozoite-positive samples were also captured outdoors (outdoor CDC-LT: n = 2; ABT: n = 3) further pointing to possibly more transmission being outdoors with these vectors. Establishment of sporozoite infection among these secondary malaria vectors is in accordance with other studies [12, 16]. The overall P. falciparum infection rate was low and this could be attributed to very minimal vector-human contact driven by exophily and efficacy of insecticides [60]. Secondary vectors with exophilic and zoophilic tendencies—or rather higher acceptance rates of alternative blood meal sources when human hosts are unavailable—may help maintain low but constant transmission [21, 61,62,63]. When factoring molecular species identifications, and the possibility that some Anopheles species identified here may not be vectors, species-specific sporozoite rates would be greater than the overall rate reported here.

Phenotypic bioassays demonstrate the susceptibility of these secondary vectors to permethrin (Table 3). The use of both wild-caught adult females without regard to abdominal (blood-fed) status and those raised from larvae enabled the determination of baseline genetic resistance (from unexposed and non-blood fed larvae) as well as resistance of adults in the field factoring in possible prior exposure as well as various physiological states. Though physiological characteristics such as age and blood feeding status can confer increased tolerance to insecticides [64], the lack of insecticide resistance seen in both sets of vectors suggests insufficient selection processes due to less exposure to indoor insecticide-based interventions (LLINs and IRS) because of both exophily and zoophily. However, their present abundance and the increased focus on the incorporation of outdoor vector control tools [65] pose a risk of pyrethroid-based control failure—were these populations to develop resistance. It is therefore vital to continue monitoring their susceptibility status since pyrethroid insecticides are still in use in public health and agriculture. The worst-case scenario is where widespread resistance to all four classes of insecticides currently in use is seen in primary vectors [6, 67]. The very low levels of survival in this study (< 1%) still point to the possibility of ongoing low levels of selection. A study that evaluates the presence of any underlying genetic markers of resistance would serve as an early warning signal of insecticide resistance before it is expressed phenotypically and may impact intervention efficacy [68]. Further insecticide resistance evaluations in conjunction with molecular identifications will further enable species-specific insecticide resistance characterizations.

Since the terms ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ are arbitrarily assigned to vectors based on characterized contributions to transmission at that point in time, changes in species compositions, insecticide pressure, climate change, changes in land use, etc., may influence the contributions of specific species to malaria transmission. For instance, in the 1950s An. rivulorum and An. parensis replaced An. funestus as the primary vector in Kenya and Tanzania [58]—the density of An. rivulorum increased almost seven times with a concurrent reduction of An. gambiae (s.l.). More recently, the lowland areas of Western Kenya have reported an increase in the density of An. rivolurum [16] attributed to reduced interspecific competition caused by current vector control interventions diminishing populations of primary vectors. This paradigm is reflected in this study where both population sizes (Table 1) and sporozoite rates of ‘secondary’ vectors are equivalent to or more than those of ‘primary’ vectors—suggesting the greater role of these vectors in transmission and the possible elevation to primary vector status based on further studies.

This small study with important outcomes suggests the need for more comprehensive collections of secondary vectors in parallel with molecular species identifications. This comprehensive analysis would include more sites and specimens for greater understanding of species compositions and their bionomics—including insecticide resistance. Collections over multiple seasons would enable temporal evaluations of these vectors and the drivers of their populations.

Conclusions

Vectors characterized as ‘secondary’ in Kisumu County are of greater potential significance to transmission as demonstrated by their higher densities and presence of sporozoites. Their exophilic and zoophilic natures indicate that they evade indoor interventions and may explain the lack of phenotypic resistance. These traits combined with their densities may amplify outdoor and residual transmission. This study indicates that the possible primary role of these ‘secondary’ vectors in malaria transmission may be the result of the apparent failure of current interventions targeting primary vectors to achieve complete malaria control. Here, local transmission dynamics may elevate the contributions of ‘secondary vectors’ to primary status—pointing to the need for routine surveillance to capture these important drivers of transmission. Further studies are required to understand the temporal species compositions and bionomics of these vectors in relation to malaria transmission in western Kenya.

Availability of data and materials

The original data applied and/or evaluated throughout the current project are accessible from the corresponding author on judicious appeal or from Kenyatta University Digital Library.

References:

WHO. World Malaria Report. 2020.

USAID. Malaria Operational Plan FY 2018-Kenya. President's Malaria Initiative; 2020.

Ghilardi L, Okello G, Nyondo-Mipando L, Chirambo CM, Malongo F, Hoyt J, et al. How useful are malaria risk maps at the country level? Perceptions of decision-makers in Kenya, Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2020;19(1):353.

Atkinson PW. Vector Biology, Ecology and Control. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010.

Afrane YA, M B, Yan G. Secondary Malaria Vectors of Sub-Saharan Africa: Threat to Malaria Elimination on the Continent? Current Topics in Malaria 2016.

Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Abaga S, Reddy VP, Caccone A, Kiszewski AE, et al. Outdoor host seeking behaviour of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes following initiation of malaria vector control on Bioko Island. Equat Guinea Malar J. 2011;10:184.

Degefa T, Yewhalaw D, Zhou G, Lee MC, Atieli H, Githeko AK, et al. Indoor and outdoor malaria vector surveillance in western Kenya: implications for better understanding of residual transmission. Malar J. 2017;16(1):443.

Wiebe A, Longbottom J, Gleave K, Shearer FM, Sinka ME, Massey NC, et al. Geographical distributions of African malaria vector sibling species and evidence for insecticide resistance. Malar J. 2017;16(1):85.

Okara RM, Sinka ME, Minakawa N, Mbogo CM, Hay SI, Snow RW. Distribution of the main malaria vectors in Kenya. Malar J. 2010;9:69.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Coetzee M, Mbogo CM, Hemingway J, et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:117.

Fornadel CM, Norris LC, Franco V, Norris DE. Unexpected anthropophily in the potential secondary malaria vectors Anopheles coustani s.l. and Anopheles squamosus in Macha, Zambia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11(8):1173–9.

Hamon J, Mouchet J. Secondary vectors of human malaria in Africa. Med Trop. 1961;21:643–60.

Nyirakanani C, Chibvongodze R, Kariuki L, Habtu M, Masika M, Mukoko D, et al. Characterization of malaria vectors in Huye District, Southern Rwanda. Tanzan J Health Res. 2017;19(3):1–10.

Bamou R, Mbakop LR, Kopya E, Ndo C, Awono-Ambene P, Tchuinkam T, et al. Changes in malaria vector bionomics and transmission patterns in the equatorial forest region of Cameroon between 2000 and 2017. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):464.

Antonio-Nkondjio C, Kerah CH, Simard F, Awono-Ambene P, Chouaibou M, Tchuinkam T, et al. Complexity of the malaria vectorial system in Cameroon: contribution of secondary vectors to malaria transmission. J Med Entomol. 2006;43(6):1215–21.

Gillies MT. The role of secondary vectors of malaria in north-east Tanganyika. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1964;58:154–8.

Mukiama TK, Mwangi RW. Seasonal population changes and malaria transmission potential of Anopheles pharoensis and the minor anophelines in Mwea Irrigation Scheme. Kenya Acta Trop. 1989;46(3):181–9.

Lobo NF, St Laurent B, Sikaala CH, Hamainza B, Chanda J, Chinula D, et al. Unexpected diversity of Anopheles species in Eastern Zambia: implications for evaluating vector behavior and interventions using molecular tools. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17952.

Durnez L, Coosemans M. Residual Transmission of Malaria: An Old Issue for New Approaches, Malaria: An Old Issue for New Approaches. Manguin S, editor. Anopheles mosquitoes - New insights into malaria vectors. InTech 2016.

Chaccour C, Killeen GF. Mind the gap: residual malaria transmission, veterinary endectocides and livestock as targets for malaria vector control. Malar J. 2016;15:24.

Killeen GF. Characterizing, controlling and eliminating residual malaria transmission. Malar J. 2014;13:330.

Kamau L, Mulaya N, Vulule JM. Evaluation of potential role of Anopheles ziemanni in malaria transmission in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2006;43(4):774–6.

St Laurent B, Cooke M, Krishnankutty SM, Asih P, Mueller JD, Kahindi S, et al. Molecular Characterization reveals diverse and unknown malaria vectors in the Western Kenyan Highlands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(2):327–35.

Zhong D, Hemming-Schroeder E, Wang X, Kibret S, Zhou G, Atieli H, et al. Extensive new Anopheles cryptic species involved in human malaria transmission in western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16139.

Davidson JR, Wahid I, Sudirman R, Small ST, Hendershot AL, Baskin RN, et al. Molecular analysis reveals a high diversity of Anopheles species in Karama, West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13(1):379.

Otten M, Aregawi M, Were W, Karema C, Medin A, Bekele W, et al. Initial evidence of reduction of malaria cases and deaths in Rwanda and Ethiopia due to rapid scale-up of malaria prevention and treatment. Malar J. 2009;8:14.

WHO. Global Malaria Programme. Eliminating malaria. 2015:243.

Bayoh MN, Mathias DK, Odiere MR, Mutuku FM, Kamau L, Gimnig JE, et al. Anopheles gambiae: historical population decline associated with regional distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets in western Nyanza Province. Kenya Malar J. 2010;9:62.

Derua YA, Alifrangis M, Hosea KM, Meyrowitsch DW, Magesa SM, Pedersen EM, et al. Change in composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012;11:188.

Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF. Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:80.

Russell TL, Lwetoijera DW, Maliti D, Chipwaza B, Kihonda J, Charlwood JD, et al. Impact of promoting longer-lasting insecticide treatment of bed nets upon malaria transmission in a rural Tanzanian setting with pre-existing high coverage of untreated nets. Malar J. 2010;9:187.

Mutuku FM, King CH, Mungai P, Mbogo C, Mwangangi J, Muchiri EM, et al. Impact of insecticide-treated bed nets on malaria transmission indices on the south coast of Kenya. Malar J. 2011;10:356.

Gatton ML, Chitnis N, Churcher T, Donnelly MJ, Ghani AC, Godfray HC, et al. The importance of mosquito behavioural adaptations to malaria control in Africa. Evolution. 2013;67(4):1218–30.

Russell TL, Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Lobo NF, Burkot TR. Successful malaria elimination strategies require interventions that target changing vector behaviours. Malar J. 2013;12:56.

Zhou G, Afrane YA, Vardo-Zalik AM, Atieli H, Zhong D, Wamae P, et al. Changing patterns of malaria epidemiology between 2002 and 2010 in Western Kenya: the fall and rise of malaria. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e20318.

Mathias DK, Ochomo E, Atieli F, Ombok M, Bayoh MN, Olang G, et al. Spatial and temporal variation in the kdr allele L1014S in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and phenotypic variability in susceptibility to insecticides in Western Kenya. Malar J. 2011;10:10.

Henry MC, Assi SB, Rogier C, Dossou-Yovo J, Chandre F, Guillet P, et al. Protective efficacy of lambda-cyhalothrin treated nets in Anopheles gambiae pyrethroid resistance areas of Côte d’Ivoire. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(5):859–64.

Githinji EK, Irungu LW, Ndegwa PN, Machani MG, Amito RO, Kemei BJ, et al. Species composition, phenotypic and genotypic resistance levels in major malaria vectors in Teso North and Teso South Subcounties in Busia County, Western Kenya. J Parasitol Res. 2020;2020:3560310.

Ochomo EO, Bayoh NM, Walker ED, Abongo BO, Ombok MO, Ouma C, et al. The efficacy of long-lasting nets with declining physical integrity may be compromised in areas with high levels of pyrethroid resistance. Malaria J. 2013;12:1.

WHO. Malaria vector control and personal protection. 2006. Report No.: 0512–3054 (Print) 0512–3054.

Ochomo EO, Bayoh NM, Walker ED, Abongo BO, Ombok MO, Ouma C, et al. The efficacy of long-lasting nets with declining physical integrity may be compromised in areas with high levels of pyrethroid resistance. Malar J. 2013;12:368.

Wanjala CL, Kweka EJ. Malaria vectors insecticides resistance in different agroecosystems in Western Kenya. Front Public Health. 2018;6:55.

Ochomo E, Subramaniam K, Kemei B, Rippon E, Bayoh NM, Kamau L, et al. Presence of the knockdown resistance mutation, Vgsc-1014F in Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis in western Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:616.

Githeko AK, Adungo NI, Karanja DM, Hawley WA, Vulule JM, Seroney IK, et al. Some observations on the biting behavior of Anopheles gambiae s.s., Anopheles arabiensis, and Anopheles funestus and their implications for malaria control. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82(3):306–15.

Bayoh MN, Walker ED, Kosgei J, Ombok M, Olang GB, Githeko AK, et al. Persistently high estimates of late night, indoor exposure to malaria vectors despite high coverage of insecticide treated nets. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:380.

Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ Sth Afr Inst Med Res. 1987;55:1–143.

Das S, Garver L, Dimopoulos G. Protocol for mosquito rearing (A. gambiae). J Vis Exp. 2007;4(5):221.

WHO. Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes. 2nd Ed. 2016.

Coetzee M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2020;19(1):70.

Ratnasingham S, Hebert PDN. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System: Barcoding. Mol Ecol Note. 2007;7(3):355–64.

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49(4):520–9.

Durnez L, Van Bortel W, Denis L, Roelants P, Veracx A, Trung HD, et al. False positive circumsporozoite protein ELISA: a challenge for the estimation of the entomological inoculation rate of malaria and for vector incrimination. Malar J. 2011;10:195.

Hadfield KH. DNA Barcoding and Genome Size: an assessment of utility for Biomonitoring Mosquito Vectors of Malaria in Western Kenya: The University of Guelph; 2013.

Miles SJ, Green CA, Hunt RH. Genetic observations on the taxon Anopheles (Cellia) pharoensis Theobald (Diptera: Culicidae). J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;86(4):153–7.

Barrón MG, Paupy C, Rahola N, Akone-Ella O, Ngangue MF, Wilson-Bahun TA, et al. A new species in the major malaria vector complex sheds light on reticulated species evolution. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14753.

Riehle MM, Guelbeogo WM, Gneme A, Eiglmeier K, Holm I, Bischoff E, et al. A cryptic subgroup of Anopheles gambiae is highly susceptible to human malaria parasites. Science. 2011;331(6017):596–8.

Conn JE. News from Africa: Novel Anopheline species transmit Plasmodium in Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(2):251–2.

Gillies MT, Smith TA. The effect of a residual house-spraying campaign in east Africa on species balance in the Anopheles funestus group the replacement of a funestus giles by A. rivulorum leeson. Bull Entomol Res. 1960;51(2):243–52.

Kawada H, Dida GO, Ohashi K, Sonye G, Njenga SM, Mwandawiro C, et al. Preliminary evaluation of insecticide-impregnated ceiling nets with coarse mesh size as a barrier against the invasion of malaria vectors. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65(3):243–6.

ter Kuile FO, Terlouw DJ, Kariuki SK, Phillips-Howard PA, Mirel LB, Hawley WA, et al. Impact of permethrin-treated bed nets on malaria, anemia, and growth in infants in an area of intense perennial malaria transmission in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(4 Suppl):68–77.

Gordicho V, Vicente JL, Sousa CA, Caputo B, Pombi M, Dinis J, et al. First report of an exophilic Anopheles arabiensis population in Bissau City, Guinea-Bissau: recent introduction or sampling bias? Malar J. 2014;13:423.

Iwashita H, Dida GO, Sonye GO, Sunahara T, Futami K, Njenga SM, et al. Push by a net, pull by a cow: can zooprophylaxis enhance the impact of insecticide treated bed nets on malaria control? Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:52.

Monroe A, Asamoah O, Lam Y, Koenker H, Psychas P, Lynch M, et al. Outdoor-sleeping and other night-time activities in northern Ghana: implications for residual transmission and malaria prevention. Malar J. 2015;14:35.

Machani MG, Ochomo E, Sang D, Bonizzoni M, Zhou G, Githeko AK, et al. Influence of blood meal and age of mosquitoes on susceptibility to pyrethroids in Anopheles gambiae from Western Kenya. Malar J. 2019;18(1):112.

Zhu L, Müller GC, Marshall JM, Arheart KL, Qualls WA, Hlaing WM, et al. Is outdoor vector control needed for malaria elimination? An individual-based modelling study. Malar J. 2017;16(1):266.

Mnzava AP, Knox TB, Temu EA, Trett A, Fornadel C, Hemingway J, et al. Implementation of the global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors: progress, challenges and the way forward. Malar J. 2015;14:173.

Ondeto BM, Nyundo C, Kamau L, Muriu SM, Mwangangi JM, Njagi K, et al. Current status of insecticide resistance among malaria vectors in Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10(1):429.

Brogdon WG, McAllister JC. Insecticide resistance and vector control. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4(4):605–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the field team—Maurice Ombok, Samson Otieno and Laban—as well as Mr. Mathiyo Kipsum for assistance with sporozoite ELISAs at the Kisumu-KEMRI lab. The authors also acknowledge the Department of Biochemistry, Biotechnology, and Microbiology at Kenyatta University and Mr. Mark Kamau for his contributions. This study was conducted at the Kenya Medical Research Institute-Kisumu (KEMRI).

Repository

The sequences supporting the conclusions of this article are available in GenBank (ITS2: MW578718 to MW578722; CO1: MW555792 to MW555794).

Funding

This study was largely funded by AMM, with material assistance from KEMRI. Funding for molecular work was provided by the Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: AMM, SM; Sample collection and processing: AMM, EO, JK; Laboratory procedures: AMM, EO, AKN, NFL; Analysis: AMM, NFL; Manuscript development and writing: AMM, SM, EO, AKN, MGM, JK, LW, NFL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project obtained ethical approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Ethical Review Board.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mustapha, A.M., Musembi, S., Nyamache, A.K. et al. Secondary malaria vectors in western Kenya include novel species with unexpectedly high densities and parasite infection rates. Parasites Vectors 14, 252 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04748-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04748-9