Abstract

Background

The NF-κB signalling pathway has been reported to be related to liver fibrosis, and we investigated whether the NF-κB signalling pathway is involved in liver fibrosis caused by secreted phospholipase A2 of Clonorchis sinensis (CssPLA2). Furthermore, expression of the receptor of CssPLA2 on the cell surface of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) may greatly contribute to liver fibrosis.

Methods

CssPLA2 was administered to BALB/c mice by abdominal injection. The levels of markers of NF-κB signalling pathway activation in mouse liver tissue were measured by quantitative RT-PCR, ELISA and western blot. Additionally, HSCs were incubated with CssPLA2, and an NF-κB signalling inhibitor (BAY 11-7082) was applied to test whether the NF-κB signalling pathway plays a role in the effect of CssPLA2. Then, the interaction between CssPLA2 and its receptor transmembrane 7 superfamily member 3 (TM7SF3) was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and GST pull-down. To determine how TM7SF3 influences the ability of CssPLA2 to cause liver fibrosis, a TM7SF3 antibody was used to block TM7SF3.

Results

The levels of the NF-ΚB signalling pathway activation markers TNF-α, IL-1β and phospho-p65 were increased by CssPLA2 in the context of liver fibrosis. In addition, the interaction between TM7SF3 and CssPLA2 was confirmed by co-IP and GST pull-down. When TM7SF3 was blocked by an antibody targeting 1–295 amino acids of TM7SF3, activation of HSCs caused by CssPLA2 was alleviated.

Conclusions

The NF-ΚB signalling pathway is involved in the activation of HSCs by CssPLA2. TM7SF3, the receptor of CssPLA2, plays important roles in liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clonorchis sinensis is a common parasite present mainly in East and South Asian countries, such as China, Korea and Vietnam [1, 2]. Infection of Clonorchis sinensis can cause cholangitis, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis and, in some serious cases, liver fibrosis or even cholangiocarcinoma [3]. Deposition of a large amount of collagen caused by the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) is key to liver fibrosis caused by infection with Clonorchis sinensis [4]. However, the mechanism by which HSCs are activated is still unclear. In our previous research, it was proven that CssPLA2 can activate HSCs and result in liver fibrosis through the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling pathway [5]. However, it is still unknown whether CssPLA2 can activate HSCs through other cell signalling pathways. Cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β have been found to be associated with the activation of HSCs in many reports [6]. The cytokines are related to the NF-κB signalling pathway and are released when this pathway is activated [7]. It is possible that CssPLA2, an enzyme itself and member of the group III phospholipase family, can activate HSCs through the NF-κB signalling pathway. However, the mechanism by which CssPLA2 causes liver fibrosis is associated with cell signalling pathways rather than its enzymatic activity [5]. Activation of cell signalling pathways is thought to be caused by the binding of a protein to its receptor on the surface of the cell [8,9,10]. In our previous research, TM7SF3, a transmembrane protein [11,12,13] and receptor of CssPLA2, was screened by a yeast two-hybrid system. TM7SF3 contains seven putative transmembrane domains, and its open reading frame encodes a protein of 570 amino acids. In this research, the ability of CssPLA2 to bind TM7SF3 is tested, and we investigate how TM7SF3 influences the ability of CssPLA2 to cause liver fibrosis.

The excretory secretory products (ESPs) of parasites play important roles in host–parasite interactions and the pathogenesis of diseases, including immunosuppression, fibrosis and carcinoma [14]. The ESPs of Clonorchis sinensis, which include 110 proteins, such as glycometabolic enzymes, detoxification enzymes and a number of RAB family proteins, are closely related to biliary diseases and liver fibrosis [15].

CssPLA2 is one of these ESPs. The gene that encodes CssPLA2 contains 828 bp. CssPLA2 is a 34-kDa protein, and we previously purified a recombinant MBP-CssPLA2 protein with a molecular weight of 76 kDa. CssPLA2 is a group III PLA2 and has been determined to cause liver fibrosis [16, 17]. It is being considered as a potential drug target [16]. It has been proven that this protein is able to bind to the HSC membrane and cause upregulation of collagen expression, which can result in liver fibrosis [16]. TM7SF3, the receptor of CssPLA2, is expressed on the membranes of HSCs and may play important roles in liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2. The NF-κB signalling pathway has been reported to be associated with liver fibrosis [18]; therefore, it is necessary to investigate the relationship between liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2 and this signalling pathway.

Methods

Expression and purification of MBP-CssPLA2 protein

The recombinant plasmids (pMAL-c2x-CssPLA2) were transformed to E. coli BL21 (DE3). Overnight cultures carrying the recombinant plasmid pMAL-c2x-CssPLA2 were inoculated in 2 L of Luria–Bertani broth medium containing 50 μg/ml of ampicillin. Cells were grown at 37 °C until the A600 had reached 0.6. The expression of protein was induced by adding IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 4 h with vigorous shaking at 250 rpm. MBP-CssPLA2 protein was purified by a single step of amylose resin under native conditions (NEB, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The endotoxin in the recombinant protein was removed by Detoxi-Gel™ Endotoxin Removing Gel (Thermo, USA), and then detected by limulus test, which confirmed that no endotoxin was found in the recombinant protein. The recombinant protein was stored at −80 °C for later use.

Measurement of the levels of NF-κB signalling pathway activation markers in mouse liver tissues

Male BALB/c mice aged 8 weeks and weighing approximately 19–20 g were raised in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment. They were divided into three groups with three mice in each group. The three groups of Balb/c mice were given an abdominal injection of 100 μg PBS, 100 μg maltose-binding protein (MBP), or 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2, twice a week for 4 weeks. The mice were sacrificed after 4 weeks.

Total RNA was extracted from mouse liver tissue by TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA). cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription from one microgram of total RNA with a reverse transcriptase kit (Thermo, Lithuania). SYBR Premix ExTaq (Takara, China) was used for PCR amplification, and the transcribed cDNA was used as a template. The sequences of the primers for mouse TNF-α were 5′-CAT CCT CTC AAA ATT CGA GTGACA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TGG GAG TAG ACA AGG TAC AAC CC-3′ (reverse primer). The sequences of the primers for mouse IL-1β were 5′-AAA TGC CAC CTT TTG ACA GTG ATG-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GCT CTT GTT GAT GTG CTG CTG-3′ (reverse primer). The sequences of the primers for mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were 5′-CAA AAT GGT GAA GGT CGG TGT G-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TGA TGT TAG TGG GGT CTG GCT C-3′ (reverse primer). Mouse GAPDH was used as the internal standard for normalization. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30 s, with an incremental increase of 0.5 °C for 5 s from 60 to 95 °C.

ELISA was used to measure the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in mouse liver tissue. Total protein was extracted from liver tissue with a total protein extraction kit (Invitrogen, USA). TNF-α (1:2000 dilutions, CST, USA) and IL-1β antibodies (1:2000 dilutions, RD, USA) were then used as the primary antibodies, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000 dilutions, CST, USA) was used as the secondary antibody. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added to each well, and 2 M H2SO4 was used to stop the reaction. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm.

Western blot analysis was used to determine the effect of the NF-κB signalling pathway on liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2. Total protein was extracted from liver tissue with a total protein extraction kit (Invitrogen, USA). A BCA protein assay kit (Transgen, China) was used to measure the protein concentration. Mouse β-actin was used as an internal standard for normalization. SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide gel) was used to separate the proteins, and the proteins were immobilized on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h before being incubated with primary antibodies (p65 antibody and phospho-p65 antibodies, 1:1000 dilution in 1% BSA, CST, USA) overnight at 4 °C. Afterwards, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000 dilution, CST, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, Pierce™ ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo, USA) was used to visualize the bands.

Analysis of the inhibitory effect of an NF-κB signalling pathway inhibitor (BAY 11-7082) on liver fibrosis

Fatty-acid-binding protein (FABP) was another ESP of Clonorchis sinensis, and here, FABP was used as a negative control. To evaluate the effect of an NF-κB signalling pathway inhibitor (BAY 11-7082) on the liver fibrosis caused by MBP-CssPLA2, human HSC cells LX-2 were divided into four groups, and incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP, 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2, 25 μg/ml FABP or 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor for 24 h.

The levels of markers of the NF-κB signalling pathway and HSC activation (TNF-α and collagen III, respectively) were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. The sequences of primers for human TNF-α were 5′-CCC AGG CAG TCA GAT CAT CTT CT-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-ATG AGG TAC AGG CCC TCT GAT-3′ (reverse primer). The sequences of primers for human collagen III were 5′-GGT CCT CCT GGA ACT GCC GGA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GAG GAC CTT GAG CAC CAG CGT GT-3′ (reverse primer). The sequences of primers for human β-actin were 5′-GTC CAC CGC AAA TGC TTC TA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TGC TGT CAC CTT CAC CGT TC-3′ (reverse primer). Human β-actin was used as the internal standard for normalization.

The supernatant of cells was collected to measure the levels of markers of the NF-κB signalling pathway and HSC activation (TNF-α and collagen III, respectively) by ELISA. TNF-α (1:2000 dilutions, CST, USA) and collagen III antibodies (1:2000 dilutions, Abcam, UK) were then applied as the primary antibodies, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was applied as the secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilutions, CST, USA).

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

We transiently over-expressed GFP-tagged CssPLA2 and Myc-tagged TM7SF3 in 293T cells for 24 h. Transfected 293T cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Gibco, USA) and incubated with an anti-PLA2 antibody and protein A-agarose beads (Pierce, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After washing five times with RIPA lysis buffer (Gibco, USA), the beads were eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 8 min at 100 °C. The samples were then analysed by western blot using anti-Myc antibodies (Proteintech, USA).

GST pull-down assay

The recombinant proteins MBP-CssPLA2 (1.26 mg) and GST-TM7SF3 (0.5 mg) were incubated with 1 mg glutathione-conjugated resin for 2 h at room temperature. GST and MBP-CssPLA2, or MBP and GST-TM7SF3, were incubated with glutathione-conjugated resin under the same conditions as negative controls. After incubation, mixtures of two proteins were purified by a single-step glutathione-conjugated resin chromatography (GE, USA) under native conditions following the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were then analysed by western blot using anti-PLA2 antibody.

Inhibition of HSCs incubated with MBP-CssPLA2 in the presence of a TM7SF3 antibody by RT-PCR

To assess whether HSCs incubated with MBP-CssPLA2 are inhibited when TM7SF3 is blocked, LX-2 cells were divided into three groups and incubated with either 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + anti-TM7SF3 antibody (1:200 dilution), 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 or PBS. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to measure the mRNA levels of collagen I and collagen III, markers of HSC activation. The sequences of primers for human collagen I were 5′-CTT CAC CTA CAG CGT CAC TG-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GGA TGG AGG GAG TTT ACA GG-3′ (reverse primer). The sequences of primers for human collagen III were 5′-GGT CCT CCT GGA ACT GCC GGA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GAG GAC CTT GAG CAC CAG CGT GT-3′ (reverse primer). Human β-actin was used as the internal standard for normalization.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 software was used to analyse the results, and the differences between the control group and the experimental group were analysed by t tests at a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

The NF-κB signalling pathway was associated with liver fibrosis in liver tissue of mice injected with MBP-CssPLA2

The level of markers of NF-κB signalling pathway activation in mouse liver tissue were measured by quantitative RT-PCR analysis, and the mRNA of TNF-α and IL-1β were determined. Unpaired t tests were performed, which showed that the differences in levels between the group of mice injected with 100 μg MBP and the group injected with 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 were significant: t(4) = 3.905, P = 0.0175 (Fig. 1a) and t(4) = 4.095, P = 0.0149 (Fig. 1b).

NF-κB signalling pathway is associated with liver fibrosis in the liver tissue of mice injected with MBP-CssPLA2. a The relative mRNA levels for TNF-α of three groups of mice that received abdominal injections of 100 μg PBS, 100 μg MBP or 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 (t(4) = 3.905, P = 0.0175). b The relative mRNA levels of IL-1β in the three groups of mice that received abdominal injections of 100 μg PBS, 100 μg MBP or 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 (t(4) = 4.095, P = 0.0149). c The absorbance of TNF-α at 450 nm in the three groups of mice that received abdominal injections of 100 μg PBS, 100 μg MBP or 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 (t(4) = 7.873, P = 0.0014). d The absorbance of IL-1β at 450 nm in the three groups of mice that received abdominal injections of 100 μg PBS, 100 μg MBP or 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 (t(4) = 7.052, P = 0.0021). e Lane 1: liver tissue of a mouse injected with 100 μg MBP; lane 2: liver tissue of a mouse injected with 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2; lane 3: liver tissue of a mouse injected with PBS. f The differences in levels between the control group and the experimental group were determined by quantitation of the western blot results. Unpaired t tests were used for statistical analysis (t(4) = 4.475, P = 0.011)

The levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in mouse liver tissue were also measured by ELISA. Both TNF-α and IL-1β were increased in liver tissue of mouse injected with MBP-CssPLA2. Unpaired t tests were performed and showed that the differences in levels between the group injected with 100 μg MBP and the group injected with 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 were significant: t(4) = 7.873, P = 0.0014 (Fig. 1c) and t(4) = 7.052, P = 0.0021 (Fig. 1d).

The levels of markers of NF-κB signalling pathway activation in mouse liver tissue were measured by western blot. p65 and phospho-p65 were measured in mouse liver tissue. Western blot of the liver tissues of mice injected with 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 showed a clear band representing phospho-p65 (Fig. 1e). Representative data from three independent experiments are presented. Significant differences between the group injected with 100 μg MBP and the group injected with 100 μg MBP-CssPLA2 were revealed by unpaired t tests (t(4) = 4.475, P = 0.011) (Fig. 1f).

The NF-κB signalling pathway inhibitor (BAY 11–7082) inhibited liver fibrosis in HSCs caused by MBP-CssPLA2

The levels of markers of NF-κB signalling pathway and HSC activation (TNF-α and collagen III, respectively) in HSCs were tested by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Unpaired t tests were performed, and it was found that the differences in levels between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml FABP were significant: t(4) = 3.335, P = 0.0290 (Fig. 2a) and t(4) = 6.113, P = 0.0036 (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the differences in levels between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP were significant: t(4) = 3.060, P = 0.0376 (Fig. 2a) and t(4) = 9.043, P = 0.0008 (Fig. 2b), and the differences between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor (BAY 11–7082) were significant: t(4) = 3.502, P = 0.0249 (Fig. 2a) and t(4) = 7.157, P = 0.002 (Fig. 2b).

NF-κB signalling pathway inhibitor (BAY 11–7082) inhibited liver fibrosis in HSCs caused by MBP-CssPLA2. a The relative mRNA levels of TNF-α in the four groups of LX-2 cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP, 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2, 25 μg/ml FABP or 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor. b The relative mRNA levels of collagen III in the four groups of LX-2 cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP, 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2, 25 μg/ml FABP or 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor. c The absorbance of TNF-α at 450 nm in the four groups of LX-2 cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP, 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2, 25 μg/ml FABP or 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor. d The absorbance of collagen III at 450 nm in the four groups of LX-2 cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP, 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2, 25 μg/ml FABP or 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor

The levels of TNF-α and collagen III in HSCs were also measured by ELISA. Unpaired t tests were performed, and it was found that the differences in levels between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml FABP were significant [t(4) = 11.03, P = 0.0004 (Fig. 2c) and t(4) = 4.606, P = 0.0100 (Fig. 2d)]. Furthermore, the differences in levels between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP were significant [t(4) = 9.341, P = 0.0007 (Fig. 2c) and t(4) = 8.136, P = 0.0012 (Fig. 2d)], and the difference between the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + 10 μΜ NF-κB inhibitor (BAY 11-7082) were significant [t(4) = 15.81, P < 0.0001 (Fig. 2c) and t(4) = 7.767, P = 0.0015 (Fig. 2d)].

The interaction between CssPLA2 and TM7SF3 was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation

To analyse the interaction between CssPLA2 and TM7SF3, GFP-tagged CssPLA2 and Myc-tagged TM7SF3 were transiently over-expressed in 293T cells. Co-immunoprecipitation revealed that CssPLA2 pulled down TM7SF3 (Fig. 3).

Confirmation of the interaction between CssPLA2 and TM7SF3 by co-immunoprecipitation. The interaction between GFP-tagged CssPLA2 and Myc-tagged TM7SF3 was assessed by co-IP followed by western blot using anti-PLA2 or anti-Myc antibodies. Tagged proteins were over-expressed in 293T cells by transient transfection. + and – indicate that the recombinant plasmid was or was not transfected into 293T cells, respectively. CssPLA2 pulled down TM7SF3

The interaction between CssPLA2 and TM7SF3 was confirmed by GST pull-down

Additionally, we over-expressed MBP-tagged CssPLA2 and GST-tagged TM7SF3 in E. coli. GST pull-down assay revealed that TM7SF3 pulled down CssPLA2 (Fig. 4).

Confirmation of the interaction between CssPLA2 and TM7SF3 by GST pull-down. The interaction between MBP-tagged CssPLA2 and GST-tagged TM7SF3 was assessed by GST pull-down followed by western blot using an anti-PLA2 antibody. GST- and MBP-tagged CssPLA2 or MBP- and GST-tagged TM7SF3 were used as negative controls. TM7SF3 pulled down CssPLA2

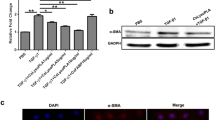

TM7SF3 antibody inhibited the activation of HSCs incubated with MBP-CssPLA2 by blocking TM7SF3

The levels of the HSC activation markers collagen I and collagen III were measured by quantitative RT-PCR, and the results revealed that since TM7SF3 plays important roles in the activation of HSCs, blocking TM7SF3 inhibited activation of HSCs by MBP-CssPLA2. Unpaired t tests were performed, and it was found that the differences in levels between the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + anti-TM7SF3 antibody and the group incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 were significant [t(4) = 12.81, P = 0.0002 (Fig. 5a) and t(4) = 6.245, P = 0.0034 (Fig. 5b)].

TM7SF3 antibody inhibited the activation of HSCs incubated with MBP-CssPLA2 by blocking TM7SF3. The mRNA levels of collagen I and collagen III in the group of LX-2 cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2 + anti-TM7SF3 antibody were lower than those in the group of cells incubated with 25 μg/ml MBP-CssPLA2. a Measurement of collagen I mRNA levels in HSCs treated with an anti-TM7SF3 antibody (t(4) = 12.81, P = 0.0002). b Measurement of collagen III mRNA levels in HSCs treated with an anti-TM7SF3 antibody (t(4) = 6.245, P = 0.0034)

Discussion

NF-κ B signalling regulates activation or apoptosis of HSCs by regulating inflammatory factors such as TNF-α. Expression of NF-κB signalling markers is upregulated in liver fibrosis [18,19,20]. Therefore, we hypothesized that CssPLA2 may activate HSCs to cause liver fibrosis through activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway and that the receptor of CssPLA2, TM7SF3, plays an important role in this process.

This study will contribute to elucidating the mechanism of HSC activation by CssPLA2 and clarify its role in the process of liver fibrosis caused by Clonorchis sinensis infection. Additionally, interfering with the signalling pathway involved in HSC activation by CssPLA2 may be a potential treatment strategy for liver fibrosis caused by Clonorchis sinensis infection.

CssPLA2-induced activation of human HSCs may involve multiple pathways. For example, the activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway is closely associated with liver fibrosis [21, 22]. The levels of phosphorylated NF-κB were obviously increased in the livers of mice infected with Clonorchis sinensis [23]. The release of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [24,25,26,27] is closely related to the activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway. The NF-κB signalling pathway is associated with a variety of inflammatory responses, such as TNF-α secretion, which regulates the activation or apoptosis of HSCs during liver fibrosis. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, phospho-p65 and other NF-κB signalling markers were increased in the progression of liver fibrosis [18,19,20]. CssPLA2 is an important ESP of Clonorchis sinensis. A multitude of reports have shown that the ESPs of Clonorchis sinensis promote the release of cytokines and induce inflammation [24,25,26,27]. CsESPs are the main causes of liver fibrosis caused by Clonorchis sinensis, which can induce HSC activation and proliferation and lead to pathological changes in biliary epithelial cells [28]. Therefore, activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway and cytokine release play important roles in the progression of liver fibrosis induced by Clonorchis sinensis infection [29,30,31,32]. Based on the above findings, it can be concluded that CssPLA2-induced activation of HSCs is not the result of the direct action of a single JNK signalling pathway on HSCs, but may also be caused by the NF-κB signalling pathway.

It is generally believed that the activation of signalling pathways is caused by the binding of proteins to their receptors on the cell surface [33,34,35,36]. TM7SF3 is located on the surface of HSCs and plays an important role in hepatic fibrosis caused by CssPLA2. Therefore, TM7SF3, which is the receptor of CssPLA2, contributes substantially to liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2.

Conclusion

The NF-κB signalling pathway is involved in the activation of HSCs by CssPLA2. The expression level of the marker of NF-κB signalling pathway activation, phospho-p65, is upregulated in the context of liver fibrosis. Additionally, TM7SF3, the receptor of CssPLA2, which is located on the surface of HSCs, is related to liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2, and inhibition of TM7SF3 with a TM7SF3 antibody relieves liver fibrosis caused by CssPLA2.

Availability of data and materials

The nucleic acid sequence of CssPLA2 supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the GenBank repository (accession numbers: DQ 974199) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/. The nucleic acid sequence of TM7SF3 supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Gene repository (Gene ID: 51768) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/51768.

Abbreviations

- Cs :

-

Clonorchis sinensis

- CssPLA2:

-

Secreted phospholipase A2 of Clonorchis sinensis

- sPLA2:

-

Secreted phospholipase A2

- ESPs:

-

Excretory and secretory products

- MBP:

-

Maltose-binding protein

- TM7SF3:

-

Transmembrane 7 superfamily member 3

References

Hong ST, Fang Y. Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:17–24.

Huang SY, Zhao GH, Fu BQ, Xu MJ, Wang CR, Wu SM, et al. Genomics and molecular genetics of Clonorchis sinensis: current status and perspectives. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:71–6.

Lun ZR, Gasser RB, Lai DH, Li AX, Zhu XQ, Yu XB, et al. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:31–41.

Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–56.

Wu YJ, Li Y, Shang M, Jian Y, Wang CQ, Bardeesi AS, et al. Secreted phospholipase A2 of Clonorchis sinensis activates hepatic stellate cells through a pathway involving JNK signalling. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:147.

Li X, Jin QW, Yao QY, Xu BL, Li LX, Zhang SC, et al. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates liver inflammation and fibrosis by regulating hepatic macrophages activation and polarization in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:72.

Liu SQ, Jia H, Hou SH, Xin T, Guo XY, Zhang GM, et al. Recombinant Mtb98 of Mycobacterium bovis stimulates TNF-α and IL-1β secretion by RAW2647 macrophages through activation of NF-κB pathway via TLR2. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1928.

Nair A, Chauhan P, Saha B, Kubatzky K. Conceptual evolution of cell signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3292.

Björnström L, Sjöberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–42.

Lan GH, Tu YH. Information processing in bacteria: memory, computation, and statistical physics: a key issues review. Rep Prog Phys. 2016;79:052601.

Akashi H, Han HJ, Iizaka M, Nakajima Y, Furukawa Y, Sugano S, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel gene encoding a putative seven-span transmembrane protein, TM7SF3. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;88:305–9.

Beck A, Isaac R, Lavelin I, Hart Y, Volberg T, Shatz-Azoulay H, et al. An siRNA screen identifies transmembrane 7 superfamily member 3 (TM7SF3), a seven transmembrane orphan receptor, as an inhibitor of cytokine-induced death of pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2845–55.

Isaac R, Goldstein I, Furth N, Zilber N, Streim S, Boura-Halfon S, et al. TM7SF3, a novel p53-regulated homeostatic factor, attenuates cellular stress and the subsequent induction of the unfolded protein response. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:132–43.

Zheng MH, Hu KH, Liu W, Li HY, Chen JF, Yu XB. Proteomic analysis of different period excretory secretory products from Clonorchis sinensis adult worms: molecular characterization, immunolocalization, and serological reactivity of two excretory secretory antigens-methionine aminopeptidase 2 and acid phosphatase. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:1287–97.

Zheng MH, Hu KH, Liu W, Hu XC, Hu FY, Huang LS, et al. Proteomic analysis of excretory secretory products from Clonorchis sinensis adult worms: molecular characterization and serological reactivity of a excretory-secretory antigen-fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:737–44.

Hariprasad G, Kaur P, Srinivasan A, Singh TP, Kumar M. Structural analysis of secretory phospholipase A2 from Clonorchis sinensis: therapeutic implications for hepatic fibrosis. J Mol Model. 2012;18:3139–45.

Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A(2) enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:1–19.

Xiao J, Ho CT, Liong EC, Nanji AA, Leung TM, Lau TY, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates fibrosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease rat model through TGF/SMAD, PI3K/Akt/FoxO1, and NF-kappa B pathways. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:187–99.

Gan F, Liu Q, Liu YH, Huang D, Pan C, Song S, et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides improve CCl(4)-induced liver fibrosis, inflammatory response and TLRs/NF-kB signaling pathway expression in wistar rats. Life Sci. 2018;192:205–12.

Gupta S, Hastak K, Afaq F, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Essential role of caspases in epigallocatechin-3-gallate-mediated inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B and induction of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2004;23:2507–22.

Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-κB in the liver-linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108–18.

de Gregorio E, Colell A, Morales A, Marí M. Relevance of SIRT1-NF-κB axis as therapeutic target to ameliorate inflammation in liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3858.

Yan C, Li B, Fan F, Du Y, Ma R, Cheng XD, et al. The roles of Toll-like receptor 4 in the pathogenesis of pathogen-associated biliary fibrosis caused by Clonorchis sinensis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3909.

Kim EM, Kwak YS, Yi MH, Kim JY, Sohn WM, Yong TS. Clonorchis sinensis antigens alter hepatic macrophage polarization in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005614.

Pak JH, Son WC, Seo SB, Hong SJ, Sohn WM, Na BK, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 expression is inversely correlated with nuclear factor-κB activation during Clonorchis sinensis infestation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;99:273–85.

Nam JH, Moon JH, Kim IK, Lee MR, Hong SJ, Ahn JH, et al. Free radicals enzymatically triggered by Clonorchis sinensis excretory-secretory products cause NF-κB-mediated inflammation in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:103–13.

Yan C, Wang YH, Yu Q, Cheng XD, Zhang BB, Li B, et al. Clonorchis sinensis excretory/secretory products promote the secretion of TNF-alpha in the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells via Toll-like receptor 4. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:559.

Li B, Yan C, Wu J, Stephane K, Dong X, Zhang YZ, et al. Clonorchis sinensis ESPs enhance the activation of hepatic stellate cells by a cross-talk of TLR4 and TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway. Acta Trop. 2020;205:105307.

Zhao L, Shi MC, Zhou LN, Sun HC, Zhang XN, He L, et al. Clonorchis sinensis adult-derived proteins elicit Th2 immune responses by regulating dendritic cells via mannose receptor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006251.

Yang YM, Kim SY, Seki E. Inflammation and liver cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:26–42.

Lin LT, Li R, Cai MY, Huang JJ, Huang WS, Guo YJ, et al. Andrographolide ameliorates liver fibrosis in mice: involvement of TLR4/NF-κB and TGF-β1/Smad2 signaling pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:7808656.

Zhu HY, Chai YC, Dong DH, Zhang NN, Liu WY, Ma T, et al. AICAR-Induced AMPK activation inhibits the noncanonical NF-κB pathway to attenuate liver injury and fibrosis in BDL rats. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:6181432.

Saczko J, Michel O, Chwiłkowska A, Sawicka E, Mączyńska J, Kulbacka J. Estrogen receptors in cell membranes: regulation and signaling. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2017;227:93–105.

Cheskis BJ, Greger JG, Nagpal S, Freedman LP. Signaling by estrogens. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:610–7.

Hui E. Understanding T cell signaling using membrane reconstitution. Immunol Rev. 2019;291:44–56.

Loustalot F, Kremer EJ, Salinas S. Membrane dynamics and signaling of the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2016;322:331–62.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Ms. Maxwell Richardson and Nicole S. Li of the University of Illinois for their help in improving the language of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant no. 2020YFC1200100), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 2019A1515010583) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81641094) to XRL, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant no. 20ykpy158) to YJW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJW and XRL conceived and designed the experiments; YJW, QH and YL performed the experiments; XRL, YJW, MS, YXY and XD analysed the data; and YJW, XRL and QH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All work was conducted with appropriate permits and permissions. All animals were housed in accordance with guidelines from the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Sun Yat-sen University (permit number SCXK Guangdong, 2009–2011).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, YJ., He, Q., Shang, M. et al. The NF-κB signalling pathway and TM7SF3 contribute to liver fibrosis caused by secreted phospholipase A2 of Clonorchis sinensis. Parasites Vectors 14, 152 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04663-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04663-z