Abstract

Background

Pentatrichomonas hominis is a flagellated protozoan that inhabits the large intestine of humans. Although several protozoans have been proposed to have a role in cancer progression, little is known about the epidemiology of P. hominis infection in cancer patients.

Methods

To determine the prevalence of P. hominis in patients with digestive system malignancies, we collected 195 and 142 fecal samples from gastrointestinal cancer patients and residents without any complaints related to the digestive system, respectively. Each sample was detected for the presence of P. hominis by nested PCR amplifying the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region and partial 18S rRNA gene.

Results

A significantly higher prevalence of P. hominis was found in cancer patients than that in the control population (41.54 vs 9.15%, χ2 = 42.84, df = 1, P < 0.001), resulting in a 6.75-fold risk of gastrointestinal cancers (OR: 6.75, 95% CI: 3.55–12.83, P < 0.001). The highest prevalence of P. hominis infection was detected in small intestine cancer patients (60%, OR: 14.88, 95% CI: 0.82–4.58, P = 0.009) followed by liver (57.14%, χ2 = 10.82, df = 1, P = 0.001) and stomach cancer patients (45.1%, χ2 = 31.95, df = 1, P < 0.001). In addition, phylogenetic analysis provided some evidence supporting that human P. hominis infection might derive from animal sources.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first report presenting the high association between P. hominis and gastrointestinal cancers. Nevertheless, whether there is any possible pathological role of P. hominis infection in cancer patients needs to be further elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer is a leading health burden worldwide, with an estimated 18.1 million new cancer cases and over nine million deaths in 2018 [1]. Gastrointestinal cancer, including colorectal, stomach, liver and esophagus cancers are the most commonly diagnosed malignancies, contributing to an incidence of over 23.8% [1, 2]. Among them, colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, closely followed by stomach and liver cancer for mortality [1]. Although great efforts have been made into the investigation and treatment of cancer, it is still an unresolved health burden due to, at least partially, lack of a detailed understanding of its causative and influence factors.

In addition to genetic/epigenetic defects and environmental factors, pathogens also play a role in the induction and/or progression of cancer. Infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria and parasites, are estimated to account for about 20% of the global cancer incidence [3, 4]. Currently, several pathogens have been identified to be able to induce or contribute to human cancers [5,6,7]. Strikingly, many of them are closely related to gastrointestinal cancers. The well-known infectious agent of stomach cancer is Helicobacter pylori which can cause chronic gastritis [8, 9]. Hepatitis B and C viruses are the most important risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma [10, 11]. In addition, the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis can cause cholangiocarcinoma [12]. Nevertheless, the relationship between pathogens and cancers is still underestimated worldwide.

Emerging evidence has linked several protozoans to cancers [13,14,15]. Trichomonas vaginalis, a sexually transmitted pathogen, was reported to associate with cervical and prostate carcinoma [16, 17]. Tritrichomonas musculis can induce the release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-18, which in turn contributes to the colorectal carcinoma in mice [18]. An epidemiological study in Uzbekistan indicated that Blastocystis sp. was highly associated with colorectal cancer (80%) [14]. Other studies also showed that Blastocystis sp. infection can facilitate the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and downregulate the host immune cell response [19, 20]. Additionally, several epidemiological studies have indicated a high association between Cryptosporidium parvum infection and colon cancer, and have suggested that C. parvum could be a potential causative agent of this disease [21, 22].

Pentatrichomonas hominis, belonging to the Trichomonadidae, inhabits the digestive tract of several vertebrates such as humans, monkeys, pigs, dogs, cats and rats [23,24,25,26,27]. This species was originally considered a commensal protozoan of the digestive tract but has subsequently been identified as a potential zoonotic parasite and a causative agent of diarrhea [28,29,30,31,32]. Pentatrichomonas hominis has also been associated with irritable bowel syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in humans [30, 33, 34]. Therefore, its impact on human health and disease remains unsettled. To investigate the P. hominis infection situation in gastrointestinal cancer patients, we conducted a case-control study in Jilin Province, China.

Methods

Collection of fecal samples

A total of 337 fecal samples were collected from the Jilin Cancer Hospital and the Second Hospital of Jilin University in China during January–July 2018. Among them, 195 specimens were submitted by inpatients with confirmed diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancers, including colorectal cancer (n = 116), stomach cancer (n = 51), esophageal cancer (n = 16), liver cancer (n = 7) and small intestine cancer (n = 5). The gastrointestinal cancer cases were determined by hospital imaging (B ultrasound; computed tomography, CT; nuclear magnetic resonance, NMR) and pathological diagnosis (gold standard). No patients in this study were found to use immunosuppressants in the hospital. Of the 195 patients, 125 were male and 70 were female with an average age of 59 (ranging from 31 to 87 years; Additional file 1: Table S1). One hundred and thirteen patients came from urban areas and 82 from rural areas. In contrast, 142 samples were collected from the control population (local residents who had no complaints relating to the gastrointestinal tract), including 71 males and 71 females with average age of 60 (ranging from 19 to 80 years; Additional file 2: Table S2). The control population who had no correlation with cancers were confirmed by health examination in the hospital. The fresh fecal samples were collected in individual containers, and were stored at − 20 °C until DNA extraction which was generally performed within 24 h. In order to avoid data deviation caused by potential cross-contamination of stool samples, the sample preparation area, PCR amplification area and sample analysis area were strictly distinguished, and an internal reference control of the sample was set up at the same time.

DNA extraction and nested PCR analysis

DNA was extracted from each fecal specimen using a Fecal DNA Rapid Extraction Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All DNA samples were detected for the presence of P. hominis by nested PCR amplifying the partial 18S rRNA gene as previously described [27]. In addition, we performed TA cloning for each positive sample and amplified the ITS1/5.8S rRNA gene/ITS2 genomic region as previously described [35]. The genomic DNA extracted from P. hominis (ATCC 3000) and ddH2O were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. All DNA specimens were analyzed twice. The positive PCR products were purified and sequenced.

Sequence analysis and phylogeny

The nucleotide sequences obtained were aligned with known sequences retrieved from the GenBank database on the BLAST website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). All novel nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MK177542–MK177552, MN173974–MN173996 and MN189982. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method under the Kimura 2-parameter model with bootstrap values out of 1000 replicates using MEGA v.7.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were used to estimate the statistical significance. All statistical tests were two-sided. Unconditional logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association of P. hominis infections with the risk of different cancers by calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All ORs were adjusted for both age and sex. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

High association of P. hominis infections with gastrointestinal cancers

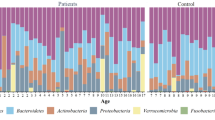

For the prevalence study, a total of 337 fecal samples were collected from 195 gastrointestinal cancer inpatients and 142 control population. Overall, the P. hominis infection rate in cancer patients was 41.54%, which was significantly higher than that in controls (9.15%, χ2 = 42.84, df = 1, P < 0.001; Fig. 1, Table 1). Intriguingly, P. hominis were found in all the studied cancer types, including colorectal cancer (37.93%, 44/116), stomach cancer (45.1%, 23/51), esophageal cancer (43.75%, 7/16), liver cancer (57.14%, 4/7) and small intestine cancer (60%, 3/5) (Table 1). Colorectal cancer accounted for 54%, stomach cancer accounted for 28%, while others accounted for 18% of P. hominis infections (Fig. 1). These results indicate a frequent occurrence of P. hominis in gastrointestinal cancers.

The age of cancer patients ranged between 31–87 years. Pentatrichomonas hominis infections were found in all age groups, with the peak in 50–60 years (45.9%, 28/61; Table 2). In addition, the infection rate in males (44.8%, 56/125) was higher than that in females (35.71%, 25/70) (Table 2). A slightly more common infection was observed in cancer patients from urban areas (43.4%, 49/113) than that from rural areas (39.02%, 31/82) (Table 2). However, there was no statistically significant difference between any of these groups. A similar tendency of the infection rates was also observed in colorectal cancer and the control population (Table 2, Additional file 3: Table S3). Nevertheless, P. hominis infection in stomach cancer was significantly enriched in males compared to females (55.26 vs 15.38%, χ2 = 6.22, df = 1, P = 0.01; Additional file 4: Table S4).

To further determine the association between P. hominis infections and gastrointestinal cancers, unconditional logistic regression analyses were conducted. Overall, P. hominis infections resulted in a 6.75-fold (95% CI: 3.55–12.83) risk of gastrointestinal cancers after adjustment for age and sex. In detail, P. hominis infections were associated with a 5.93-fold (95% CI: 3.00–11.77), 7.11-fold (95% CI: 3.13–16.11), 34.85-fold (95% CI: 5.94–204.40), 20.38-fold (95% CI: 3.29–126.28) and 14.77-fold (95% CI: 1.03–211.18) risk of colorectal, stomach, esophageal, liver and small intestine cancer, respectively. These results suggest a high association of P. hominis with gastrointestinal cancers.

Molecular characterization of P. hominis polymorphism

BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) analyses of the partial 18S rRNA gene and the ITS region indicated that P. hominis in both control population and cancer patients were homologous to the strains isolated from dogs, cats, etc. Of the 94 partial 18S rRNA sequences obtained, 81 sequences displayed 100% identity to the reference sequence (GenBank: KJ404269; Changchun canine strain). Thirteen sequences were assigned to novel types with a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) compared to KJ404269 (99% identity) including substitutions, insertion and deletion of a single nucleotide (Fig. 2, Table 3). These sequences were classified into 10 types (CCH2–11, Table 3). Additionally, the ITS sequences obtained were homologous to the reference sequence (GenBank: KJ404270.1; Changchun canine strain) with a number of SNPs. These sequences were classified into 24 classes (CCH-ITS1–CCH-ITS24). Finally, the phylogenetic tree demonstrated that all the sequences obtained belonged to P. hominis based on the maximum likelihood method (Fig. 3).

Alignment of the sequences of partial 18S rRNA gene of P. hominis isolated from humans in the present study with reference sequences. Nucleotides that differ from those in the reference sequences are indicated. Dots represent the consensus nucleotides in all the sequences. Abbreviation: CCH, China Changchun human

Phylogenetic relationships between P. hominis obtained in the present study (marked with blue circle or blue triangle) and other known trichomonads were inferred using the maximum likelihood analysis of the partial 18S rRNA gene and ITS sequence based on the genetic distance calculated by Kimura 2-parameter model. The numbers at the branches represent the percentage of replicate trees in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates). a 18S rRNA sequences. b ITS sequences. Abbreviation: CCH, China Changchun human

Discussion

Pentatrichomonas hominis is an anaerobic and flagellated protozoan that infects a wide range of hosts including humans [23, 27]. In a previous study [27], the prevalence of P. hominis infection in dogs, humans and monkeys was found to be 27.38%, 4.00% and 46.67%, respectively. Currently, P. hominis is considered to be a potential zoonotic parasite and can cause several symptoms, such as diarrhea [31, 32]. However, the study of the association between P. hominis infection and cancer is still lacking. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report on the prevalence and polymorphism of P. hominis in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Pentatrichomonas hominis was found to be significantly associated with gastrointestinal cancers. Typically, P. hominis infection was highly associated with colorectal cancer (OR: 5.93; 95% CI: 3.00–11.77) and stomach cancer (OR: 7.11; 95% CI: 3.13–16.11), indicating that P. hominis infection could be a potential risk factor for these cancers.

Pentatrichomonas hominis belongs to Trichomonadida which are often morphologically recognized by the presence of three to five anterior flagella and a single recurrent flagellum [36]. Trichomonadids are composed of a large group of common protozoans including both pathogenic and commensal species. Among them, only four species are considered as human parasites, including T. vaginalis, Trichomonas tenax, P. hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis. The first species is human-specific, while the other three are potentially zoonotic [31, 37]. A recent study demonstrated that T. musculis, a murine trichomonadid, can exacerbate colorectal cancer development through induction of IL-18 in mice [18]. This study also showed that D. fragilis is the closest human ortholog of T. musculis, suggesting it may also play a role in cancer progression [18]. In addition, T. vaginalis was shown to be associated with cervical and prostate cancers [16, 17]. Thus, the pathological role of P. hominis in cancer is speculated. Indeed, we here identified a high association between P. hominis infections and gastrointestinal cancers. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection can cause a 6.75-fold (95% CI: 3.55–12.83) risk of gastrointestinal cancers. The high prevalence of P. hominis was not only observed in colorectal cancer, but also in other gastrointestinal cancers, including stomach cancer, liver cancer, esophageal cancer and small intestine cancer.

It is well-known that P. hominis mainly colonizes the large intestine in humans [23, 27]. How P. hominis infections influence other gastrointestinal cancers is elusive. Although unlikely, it is possible that P. hominis inhabit the atypical locations, such as liver and small intestine. In support of this speculation, P. hominis has been rarely identified in the respiratory tract [33], suggesting that P. hominis can grow outside of its usual locations. Alternatively, P. hominis infections may alter the microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract, which in turn affects these cancers. It has been shown that microbiota are highly associated with gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal cancers, such as colorectal cancer, liver cancer and breast cancer [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Meanwhile, infections with several parasites can perturb the diversity and relative abundance of intestinal microbiota. For instance, persistent infection with Trichuris muris, a parasite localized in the large intestine, dramatically decreased the diversity of bacterial communities, while increasing the relative abundance of the genus Lactobacillus in the murine intestine [44]. Cryptosporidium parvum infections also perturbed the composition of intestinal microbiota in mice [45]. In addition, Blastocystis spp. alone or in co-infections with D. fragilis decreased the relative abundance of Bacteroides and Clostridial cluster XIVa and increased the levels of Prevotella [46]. Future studies are warranted to investigate how P. hominis infections could potentially influence, or alternatively be favored by, different gastrointestinal cancers.

A variety of species have been identified as hosts of P. hominis, including humans, dogs, pigs, monkeys, cats, sheep and cattle [23,24,25,26,27, 47]. In the present study, sequence analysis revealed that 81 partial 18S rRNA sequences obtained were 100% identical to that of P. hominis Changchun canine strain (GenBank: KJ404269) isolated from a dog [48], and 13 novel sequences displayed nucleotide variations compared with KJ404269. We further identified that the sequence KJ404269 is identical with MG015711 and MF991102 isolated from cats and goats, respectively (Fig. 2) [25, 49]. Additionally, the ITS sequences obtained were homologous to the reference strain KJ404270.1 isolated from a dog [48]. Therefore, we speculate that cancer patients might acquire P. hominis infections from the fecal material of dogs, cats or goats. Furthermore, a phylogenetic analysis clearly showed that partial 18S rRNA and ITS sequences were genetically clustered with known P. hominis sequences isolated from dogs, cats, goats, etc, suggesting potential zoonotic transmission.

Conclusions

This case-control study represents the first report of the association between P. hominis infections and gastrointestinal cancers. It evokes the reconsideration of the pathogenic role of P. hominis in human health. The polymorphism of P. hominis identified in this study supports potential zoonotic transmission. Further work is required to elucidate the pathological function of P. hominis in cancer induction and/or progression.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and analyzed during this study are included within this article and its additional files. The newly generated sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the Accession Numbers MK177542–MK177552, MN173974–MN173996 and MN189982.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ITS:

-

internal transcribed spacer

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018.

Blaser MJ. Understanding microbe-induced cancers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2008;1:15–20.

zur Hausen H. The search for infectious causes of human cancers: where and why (Nobel lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5798–808.

de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–15.

de Martel C, Franceschi S. Infections and cancer: established associations and new hypotheses. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:183–94.

Ziegler JL, Buonaguro FM. Infectious agents and human malignancies. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3455–64.

Correa P, Fox J, Fontham E, Ruiz B, Lin YP, Zavala D, et al. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinoma Serum antibody prevalence in populations with contrasting cancer risks. Cancer. 1990;66:2569–74.

Niwa T, Tsukamoto T, Toyoda T, Mori A, Tanaka H, Maekita T, et al. Inflammatory processes triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection cause aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1430–40.

WHO/IARC. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Hepatitis virus, vol. 59. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

Raza SA, Clifford GM, Franceschi S. Worldwide variation in the relative importance of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1127–34.

IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, vol. 61. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994.

Zhang W, Ren G, Zhao W, Yang Z, Shen Y, Sun Y, et al. Genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and subtyping of Blastocystis in cancer patients: relationship to diarrhea and assessment of zoonotic transmission. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1835.

Toychiev A, Abdujapparov S, Imamov A, Navruzov B, Davis N, Badalova N, et al. Intestinal helminths and protozoan infections in patients with colorectal cancer: prevalence and possible association with cancer pathogenesis. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:3715–23.

Tan TC, Ong SC, Suresh KG. Genetic variability of Blastocystis sp isolates obtained from cancer and HIV/AIDS patients. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1283–6.

Zhang ZF, Graham S, Yu SZ, Marshall J, Zielezny M, Chen YX, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis and cervical cancer. A prospective study in China. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:325–32.

Stark JR, Judson G, Alderete JF, Mundodi V, Kucknoor AS, Giovannucci EL, et al. Prospective study of Trichomonas vaginalis infection and prostate cancer incidence and mortality: Physiciansʼ Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1406–11.

Chudnovskiy A, Mortha A, Kana V, Kennard A, Ramirez JD, Rahman A, et al. Host-protozoan interactions protect from mucosal infections through activation of the inflammasome. Cell. 2016;167(444–56):e14.

Chandramathi S, Suresh K, Kuppusamy UR. Solubilized antigen of Blastocystis hominis facilitates the growth of human colorectal cancer cells, HCT116. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:941–5.

Chan KH, Chandramathi S, Suresh K, Chua KH, Kuppusamy UR. Effects of symptomatic and asymptomatic isolates of Blastocystis hominis on colorectal cancer cell line, HCT116. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2475–80.

Sulzyc-Bielicka V, Kuzna-Grygiel W, Kolodziejczyk L, Bielicki D, Kladny J, Stepien-Korzonek M, et al. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with colorectal cancer. J Parasitol. 2007;93:722–4.

Osman M, Benamrouz S, Guyot K, Baydoun M, Frealle E, Chabe M, et al. High association of Cryptosporidium spp infection with colon adenocarcinoma in Lebanese patients. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189422.

Wenrich DH. Morphology of the intestinal trichomonad flagellates in man and of similar forms in monkeys, cats, dogs and rats. J Morphol. 1944;74:189–211.

Li W, Li W, Gong P, Meng Y, Li W, Zhang C, et al. Molecular and morphologic identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in swine. Vet Parasitol. 2014;202:241–7.

Li WC, Wang K, Gu Y. Occurrence of Blastocystis sp and Pentatrichomonas hominis in sheep and goats in China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:93.

Kim YA, Kim HY, Cho SH, Cheun HI, Yu JR, Lee SE. PCR detection and molecular characterization of Pentatrichomonas hominis from feces of dogs with diarrhea in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2010;48:9–13.

Li WC, Ying M, Gong PT, Li JH, Yang J, Li H, et al. Pentatrichomonas hominis: prevalence and molecular characterization in humans, dogs, and monkeys in Northern China. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:569–74.

Honigberg BM, Burgess DE. Trichomonas of importance in human medicine including Dientamoeba fragilis. In: Kreier JP, editor. Parasitic Protozoa. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. p. 1–57.

Gookin JL, Birkenheuer AJ, St John V, Spector M, Levy MG. Molecular characterization of trichomonads from feces of dogs with diarrhea. J Parasitol. 2005;91:939–43.

Meloni D, Mantini C, Goustille J, Desoubeaux G, Maakaroun-Vermesse Z, Chandenier J, et al. Molecular identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in two patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:933–5.

Maritz JM, Land KM, Carlton JM, Hirt RP. What is the importance of zoonotic trichomonads for human health? Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:333–41.

Dogan N, Tuzemen NU. Three Pentatrichomonas hominis cases presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2018;42:168–70.

Jongwutiwes S, Silachamroon U, Putaporntip C. Pentatrichomonas hominis in empyema thoracis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:185–6.

Compaore C, Kemta Lekpa F, Nebie L, Niamba P, Niakara A. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Rheumatology. 2013;52:1534–5.

Kamaruddin M, Tokoro M, Rahman MM, Arayama S, Hidayati AP, Syafruddin D, et al. Molecular characterization of various trichomonad species isolated from humans and related mammals in Indonesia. Korean J Parasitol. 2014;52:471–8.

Felleisen RS. Host-parasite interaction in bovine infection with Tritrichomonas foetus. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:807–16.

Kellerova P, Tachezy J. Zoonotic Trichomonas tenax and a new trichomonad species, Trichomonas brixi n. sp., from the oral cavities of dogs and cats. Int J Parasitol. 2017;47:247–55.

Torres PJ, Fletcher EM, Gibbons SM, Bouvet M, Doran KS, Kelley ST. Characterization of the salivary microbiome in patients with pancreatic cancer. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1373.

Poutahidis T, Varian BJ, Levkovich T, Lakritz JR, Mirabal S, Kwok C, et al. Dietary microbes modulate transgenerational cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1197–204.

Pevsner-Fischer M, Tuganbaev T, Meijer M, Zhang SH, Zeng ZR, Chen MH, et al. Role of the microbiome in non-gastrointestinal cancers. World J Clin Oncol. 2016;7:200–13.

Meng C, Bai C, Brown TD, Hood LE, Tian Q. Human gut microbiota and gastrointestinal cancer. Genom Proteom Bioinf. 2018;16:33–49.

Wu N, Yang X, Zhang R, Li J, Xiao X, Hu Y, et al. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients. Microb Ecol. 2013;66:462–70.

Yang Y, Jobin C. Novel insights into microbiome in colitis and colorectal cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:422–7.

Holm JB, Sorobetea D, Kiilerich P, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Estelle J, Ma T, et al. Chronic Trichuris muris infection decreases diversity of the intestinal microbiota and concomitantly increases the abundance of Lactobacilli. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125495.

Ras R, Huynh K, Desoky E, Badawy A, Widmer G. Perturbation of the intestinal microbiota of mice infected with Cryptosporidium parvum. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45:567–73.

O’Brien Andersen L, Karim AB, Roager HM, Vigsnæs LK, Krogfelt KA, Licht TR, et al. Associations between common intestinal parasites and bacteria in humans as revealed by qPCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:1427–31.

Dufernez F, Walker RL, Noel C, Caby S, Mantini C, Delgado-Viscogliosi P, et al. Morphological and molecular identification of non-Tritrichomonas foetus trichomonad protozoa from the bovine preputial cavity. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2007;54:161–8.

Li WC, Gong PT, Ying M, Li JH, Yang J, Li H, et al. Pentatrichomonas hominis: first isolation from the feces of a dog with diarrhea in China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1795–801.

Bastos BF, Brener B, de Figueiredo MA, Leles D, Mendes-de-Almeida F. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in two domestic cats with chronic diarrhea. JFMS Open Rep. 2018;4:2055116918774959.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaoou Li and Lianzhi Cui (Jilin Cancer Hospital) for assistance of the fecal specimen collection.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No .2017YFD0501305) and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30970322).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ, NZ and XY conceived and designed the experiments. HZ, NZ, PG and JL performed the experiments. NZ and HZ analyzed data. YY, TL, ZC, CT and XL helped with the fecal specimen collection. NZ and XZ wrote the manuscript. ZL helped with revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Ethics Committees of Jilin Cancer Hospital and the Second Hospital of Jilin University (Reference No. 201712-047), and was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The fecal samples collected for the detection of P. hominis were approved by all the volunteers and cancer patients involved in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Information on the sex, age, residence, cancer subtype and P. hominis infection for 195 gastrointestinal cancer patients.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Information on the sex, age, residence and P. hominis infection for the control population.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Prevalence of P. hominis infections in the control population by selected characteristics.

Additional file 4: Table S4.

Prevalence of P. hominis infections in stomach cancer patients by selected characteristics.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Zhang, H., Yu, Y. et al. High prevalence of Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Parasites Vectors 12, 423 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3684-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3684-4