Abstract

Background

Lutzomyia longipalpis, the vector for the causal agent of visceral leishmaniasis (VL), has extended its distribution in the southern cone in the Americas. The first urban record of Lu. longipalpis in Argentina was from the City of Clorinda in 2004. The aim of this study was to analyse the monthly distribution and abundance of Lu. longipalpis and to evaluate its association with environmental and climatic variables in Clorinda City, Province of Formosa.

Methods

Phlebotominae sampling was performed using CDC light mini-traps that were placed in different sites of the city between January 2012 and December 2013. Environmental variables including the normalised difference vegetation index, normalized difference water index, land surface temperature and precipitation were evaluated using a spatiotemporal model.

Results

A total of 4996 phlebotomine sandflies were captured during the study period, and eight species were reported: Lu. longipalpis, Migonemyia migonei, Nyssomyia whitmani, Ny. neivai, Brumptomyia guimaraesi, Evandromyia cortelezzii/sallesi, Psathyromyia bigeniculata and Expapillata firmatoi. This is the first urban record of Ex. firmatoi in Argentina. Lutzomyia longipalpis was the most abundant species between 2012 and 2013, and it appeared in all the sampled sites. Moreover, the model applied showed that ground humidity and temperature were significantly associated with the abundance of Lu. longipalpis.

Conclusions

This longitudinal approach at city scale allows for modelling that explains more than 60% of the temporal variability of the abundance of Lu. longipalpis based exclusively on satellite obtained data. The results support the hypothesis of steady ‘hot spots’ of abundance with time, while other sites could change its abundance due to eventual microenvironment changes. The Lu. longipalpis abundance driving factors are breeding site-related variables, highlighting the importance both for modelling and surveillance to use lag data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neglected diseases are a group of infectious diseases, usually parasitic and chronic, that principally affect poor populations with limited access to healthcare. The World Health Organization (WHO) has listed 17 diseases within this group and among them is leishmaniasis [1]. Leishmaniasis is a group of zoonotic diseases caused by more than 20 species of parasites of the genus Leishmania (Trypanosomatidae) and is transmitted to humans through the bite of a hematophagous insect belonging to the family Psychodidae, subfamily Phlebotominae. There are two main clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis caused by these parasites: tegumentary (cutaneous and mucocutaneous) and visceral or kala-azar (VL). These types not only vary clinically but also on the vector, the reservoir and the species of parasite involved.

Of these two, VL is the most serious, with an estimated worldwide incidence of 200,000 to 400,000 cases per year [2]. American VL, caused by Leishmania infantum, has a case-fatality rate of 6.6% and Brazil reports more than 96% of the cases, but the Southern Cone (South-Midwest of Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina) showed the most significant increase in VL incidence in the Americas during this century [3]. This is associated with the southern spread of L. infantum and its main vector, the synanthropic phlebotomine Lutzomyia longipalpis which led to a new scenario of transmission in urban areas [4, 5].

In the South-Midwest of Brazil, in Mato Grosso do Sul State, the epidemic pattern related to anthropogenic environmental disturbances and migration generated a human VL report increase of 1510% between 2001 and 2006 in Campo Grande City [6, 7]. The highest climatic suitability for Lu. longipalpis has been observed in the southern area of the state on the border with Paraguay, including Ponta Porá and even in northern Paraguay [8, 9]. Consequently, Paraguay reported one human VL case during the year 2000, but afterward an average of 111 cases/year (75–145) between the years 2010 and 2015; 90% of these are from the most populated area (Asunción Capital District, and departments of Central, Paraguarí and Cordillera) [10, 11]. However, the canine VL seroprevalence in Asuncion City already ranged from 3.1 to 11.8% between 1997 and 1999 [12], and it reached up to 48.9% in Lambare (Asuncion Capital District) in a survey performed in 2004–2006 [13].

In 2004, Lu. longipalpis associated with urban scenarios in Argentina was first reported [14]. After this report from Clorinda City and-Puerto Pilcomayo, new reports followed, providing evidence for the spread of Lu. longipalpis. The first human VL autochthonous case in Posadas occurred in 2006, 295 km east from Clorinda also bordering with Paraguay [15]. In 2010, Lu. longipalpis was first recorded in Salto, Uruguay, 675 km south from Clorinda bordering with Argentina [16]. In 2013, Lu. longipalpis was first recorded in Tartagal, Argentina, 692 km north-west from Clorinda and 60 km from the border with Bolivia [17].

The first urban captures of Lu. longipalpis in Argentina during June and December 2004 were in three out of 18 sampled sites, one in a courtyard within the city of Clorinda and two in the contiguous rural-periurban Puerto Pilcomayo associated with pigsties [14]. In surveys performed during October 2007 in the same area, Lu. longipalpis was present in 10 out of 140 sampled sites again in Clorinda-Puerto Pilcomayo, including those sites were vector presence was observed in 2004 [18]. Despite the fact that the vector found in Asuncion belongs to the pheromone Lu. longipalpis species complex associated with urban spread [19, 20], in Clorinda the results after 3 years of the first report showed a clustered pattern with restricted dispersion. Clorinda is 40 km away from Downtown Asuncion, and there is an intense human transit through bridges for pedestrians and automobiles that connect both cities.

Given this situation, this study was conducted 5 years after the second survey in both Clorinda and Puerto Pilcomayo to assess the monthly distribution and abundance of Lu. longipalpis in sites with previous captures and sites with no previous captures, and to evaluate its association with environmental and climatic satellite variables. The results presented here aim to provide an insight into the spatial population dynamics at the city spatial-scale. We hope these results contribute to the understanding of the permanence-expansion of VL vectors in urban areas in the Americas and facilitate the design of improved time-space focused surveillance and control strategies at the mesoscale/urban focus level.

Methods

Study area

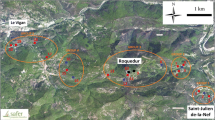

Clorinda City (25°17′S, 57°43′W, and 62 m above sea level) is located in Formosa Province, on the Pilcomayo-Paraguay River which is also the international border between Argentina and Paraguay (Fig. 1). Three pedestrian bridges and many fords link Clorinda to Nananawa in Paraguay, which is 40 km from Asunción, Paraguay’s capital city and 115 km from the capital of the Province of Formosa. The city belongs to the Eastern (humid) Chaco ecoregion [21]. The climate is subtropical without a dry season, humid subtropical climate (Cfa) type according to the Köeppen-Greiger classification, with a mean annual median temperature of 23 °C (ranging from -2 °C to 43 °C), and an average annual rainfall of 1300 mm. The driest period in this region is from June to August [22]. Clorinda’s urban area has 53,506 inhabitants distributed in 980 blocks, while Puerto Pilcomayo is an area of 669 inhabitants contiguous to the south-east border of the city where rural-periurban houses are scattered along 11 km on the river bank [23].

Phlebotominae sampling

CDC light mini-traps [24] were placed in peridomestic habitats overnight during two consecutive nights once a month between January 2012 and December 2013. The captures were performed during the third week of the month, but if the rain prevented the activity, the sampling was performed during the fourth week of the month. This only happened twice, during February 2012 and June 2013. The sample sites were located mostly in Clorinda City (15) and five were located in Puerto Pilcomayo, including the ten sites with previous records of Lu. longipalpis [14, 21]. Five sites within Clorinda with no previous records of the vector but with environments prone to have phlebotomine [25] were also included. Species identification was performed following Galati’s key [26] with abbreviations according to Marcondes [27].

Environmental variables and correlation analyses

The normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI), and normalised difference water index (NDWI) from MODIS MOD13Q1 satellite products with capture every 16 days at 250-m spatial resolution were used [28,29,30]. NDVI and NDWI are dimensionless indexes that range between -1 and 1. For NDVI, negatives value mean water, values near to 0 mean bare soil and for positive values, the NDVI grow when there is more abundant and denser vegetation. Land surface temperature (LST) from MODIS MOD11A2 satellite product, stored on a 1-km Sinusoidal grid is the average value of clear-sky LSTs during an 8-day period, validated at Stage-2, corresponding to daytime (LSTday) and to night time (LSTnight) as maximum and minimum temperature [31]. Local precipitation was obtained from the tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) [32].

To explore the association of these variables with Lu. longipalpis abundance, the following were computed: (i) time series and mean monthly values for each variable; (ii) mean values of all the pixels involved according to the satellite product pixel area for each site; (iii) time lags of these mean values with one (lag1), two (lag2) and three (lag3) months before the sampling month; (iv) the Pearson correlation between variables at each time; (v) a generalized linear model (GLM), with a Poisson Lu. longipalpis abundance distribution, to explain vector abundance with the variables that show the highest correlation and significance values [33, 34].

Results

In the two-year trapping period, 4996 Phlebotomine were captured belonging to eight species. In 2012, Lu. longipalpis was the most prevalent with 98.53% of the total captures. In 2013, Lu. longipalpis was also the most prevalent, but the captures were lower than in 2012 (89.13%), while Mg. migonei, Nyssomyia whitmani, Ny. neivai and Evandromyia cortellezzii/sallesi captures were higher, accounting for 20.89% of the entire phlebotomine population in 2013. Furthermore, two species, Psathyromyia bigeniculata and Expapillata firmatoi, that were not found in 2012 were captured in 2013 (Table 1).

Lutzomyia longipalpis appeared in all the sampled sites, but there were differences in abundance among sites and years (Fig. 2). Sites 3 and 17 showed the highest abundances over the capture period. In 2013, there was a noteworthy increase of abundance in sites 11 and 13 located in Puerto Pilcomayo, while most of the other sites had less Lu. longipalpis during the second year (Fig. 2).

The monthly time series of environmental variables obtained is presented in Fig. 3 jointly to Lu. longipalpis abundance. Here it is possible to observe the different temporal patterns of the environmental variables and the correlation between them. While the peak of abundance was coincidental with high values of almost all variables except TRMM, other periods of increase in the variables values are not associated with higher abundances of Lu. longipalpis. The temporal pattern of abundance of Lu. longipalpis seems not to follow the pattern of just one critical variable of this environmental series through the studied period. This fact shows that it is a complex system where many variables influenced together on several scales, even some not included in this macro-environmental variables analysis.

However, to better assess the relationship between Lu. longipalpis abundance and the environmental variables, a correlation analysis was made adding the three lag functions calculated. The results are shown in Fig. 4. To measure the importance and significance of the Pearson correlations, the P-values were also analysed (Table 2). The only significant correlation between the environmental and climatic variables and Lu. longipalpis abundance during the capture period was the dependent variable LST and LST time lags.

Pearson correlation between environmental variables and Lu. longipalpis abundance. Colour and shape of the circles are proportional to the correlation coefficients. Abbreviations: NDVI: normalised difference vegetation index, NDWI: normalised difference water index, LST: land surface temperature, TRMM: tropical rainfall measuring mission

With these results, a generalised linear model was tested (Table 3). In the formula, each environmental variable was included, using the most strongly correlated function. LSTdaylag2, LSTnightlag2, NDVIlag3, NDWIlag3, TRMMlag1, were used to represent LST, NDVI, NDWI and TRMM, respectively. The family used in the model was Poisson, representing the distribution of the abundance variable.

The actual abundance of Lu. longipalpis obtained through captures and the simulated abundance generate had a good correlation (Pearson coefficient 0.75, P-value = 1e-04). The total and simulated abundances are plotted in Fig. 5.

Discussion

Satellite information of environmental variables was used to analyse the influence of these on the abundance of Lu. longipalpis. This is considered a robust input to explain vectors abundance [29, 35, 36]. This methodology has been tested for other vectors such as Aedes aegypti [22, 37] but in this study, we developed a specific methodology for Lu. longipalpis that included more variables and the use of a different statistical approach. This methodology is more robust than in previous studies of vector abundance due to the statistical nature of the model used (GLM), which has been tested to be better suited for analysing ecological relationships, which can be poorly represented by classical Gaussian distributions [34, 38].

Even though Lu. longipalpis was first reported in Argentina in 1951 [39], it was not until 2004 that Argentina was considered at risk for VL transmission given that the vector was found for the first time in an urban setting (i.e. in Clorinda) [14]. Although the first human case of VL in Argentina occurred in 1924 [40], the first confirmed autochthonous case in the country was not reported until 2006, with a human case caused by vectorial transmission of the parasite from an infected canine [15]. This was after Brazil, and Paraguay first reported cases of VL in humans in Mato Grosso do Sul in 1998 and Asunción in the year 2000 [41,42,43]. Currently, VL is autochthonous in 12 countries of the Americas; between 2001 and 2013, 45,490 cases were registered with an annual average of 3499 cases [3].

This study was performed in the city of Clorinda 11 years after the first report of Lu. longipalpis. A total of eight phlebotomine species were registered, including Lu. longipalpis, Mg. migonei, Br. guimaraesi, Ny. neivai, Evandromyia cortellezzii/sallesi, Ny. whitmani, Ex. firmatoi and Pa. bigeniculata; the last three species had not been previously reported in other studies from Clorinda [18]. Moreover, this is the first time that Ex. firmatoi is reported in an urban scenario in Argentina.

Lutzomyia longipalpis was the most abundant species, representing 89.13% of the total specimens captured. This is also the highest percent abundance registered since 2009 when Lu. longipalpis was found in ten areas of Clorinda and Puerto Pilcomayo where it represented 80.6% of the captured phlebotomine, with a male prevalence of 75.9% [18].

These results confirm the urbanisation trend of Lu. longipalpis and visceral leishmaniasis urban transmission in the southern cone of the Americas, in areas with previous records of cutaneous leishmaniasis, mainly due to rural and periurban transmission. Regular entomological surveillance, together with VL case surveillance via increased awareness of human and domestic animals health agents, should be performed in vulnerable areas without reports of Lu. longipalpis or cases.

Throughout the study, variations were found regarding the species frequency and the representability of the species captured. Nonetheless, Lu. longipalpis was the species with the highest representation, with 98.5 and 74.1% of the total of species captured between 2012 and 2013. These results are similar to those reported by other authors in studies performed in urban scenarios from other areas of northern Argentina like Posadas, Misiones [25, 44], Santo Tome, Corrientes [45], Tartagal, Salta [17] and Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil [46].

Regarding the periods of highest abundance, summer and the beginning of autumn were the times of the year with the greatest quantity of phlebotomine captured, while winter was the time with the least number of them. These results are in agreement with studies performed by de Oliveira et al. [41] where the greatest quantity of captured phlebotomine was during the month of February after a period of abundant rain.

The capture sites covered different environments present in the urban areas of Clorinda and rural areas of Puerto Pilcomayo. Nonetheless, not all the sites showed the same abundance of Lu. longipalpis. In 2012, sites 3 and 17 were the sites with the highest abundance, but in the same period in 2013, the sites with the highest abundance where sites 11, 13 and 17. A study performed by Fernandez et al. [47] with a time-transversal sampling strategy indicated that the distribution of Lu. longipalpis in Posadas followed a time-variable “island” pattern of high abundance or ‘hot spots’. The current study conducted in Clorinda during 2 years of sampling has shown is that some of these “islands” are stable and others are variable through time.

With the constant/continuous sampling data obtained in this study, it was possible to determine a model to evaluate environmental variables that might influence the population dynamics of Lu. longipalpis. This is not always considered due to the sampling time-transversal methodology constraints seen in most studies. The model showed that ground humidity and temperature are the variables that could be significantly determining the abundance of the species and also but not equally strong, the vegetation in the area. Land surface temperature (LST), in particular, is a key variable in climatological and environmental studies [31, 48,49,50,51,52] and the current study has shown a high, positive and significant correlation with the abundance of Lu. longipalpis.

The variables represented by NDVI and NDWI could be eventually associated with the abundance of phlebotomines through the characterisation of breeding sites. Optimal breeding sites have a high content of organic matter in decomposition, soil availability and humidity but scarce vegetation and usually have some domestic or peridomestic use. Examples of breeding sites include, but are not limited to, abandoned buildings, the soil in human dwellings, animal burrows, street rubbish, soil at the base of old walls, dry excreta from small domestic animals and soil cracks [53].

More specifically, studies on breeding sites of Lu. longipalpis from Brazil [4, 53] have shown that the sites with the greatest rates of abundance were animal pens and between rocks. Both of these types of sites have very low values of NDVI, which measures the vegetation cover of a surface, referring to the amount of chlorophyll, which may explain the negative association seen in the current model. On the other hand, these same authors characterise breeding sites as places with humidity, which is in agreement with the positive correlation found for NDWI in the current study.

It is important to note that in the present work we have been able to obtain a model that represents more than 60% of the temporal variability of abundance based exclusively on satellite variables. Given that Lu. longipalpis is a species with a high dependency on microscale factors, a value of 60% is satisfactory for our purposes and it would be hard to obtain a value much higher than the one obtained herein. However, a negative point of the model is that it does not generate a good representation of some peaks of abundance (Jul 2012 Jan 2013). In order to be able to elucidate this difference, it would be necessary to perform further analyses. Regardless, it is worth higlighting that this model uses delayed satellite variables (from 1 or 2 months ago), which means that it is an excellent tool for temporary prediction and can therefore be used for the planning of control actions by the health authorities.

Conclusions

This study represents a macro spatial approach of the VL vector in the city, focused on its temporal distribution, different from other approaches [25, 54]. The results of this study highlight the importance of designing and applying tailored strategies for entomological surveillance control that are based on the different epidemiological scenarios and population dynamics of Lu. longipalpis. These results support the hypothesis of ‘hot spots’ of abundance through time that could be forecasted by this remote sensing approach, while other sites increase or decrease its abundance from year to year due to microenvironmental changes that require micro-scale analysis, which is already being tested in ongoing studies. Abundance of Lu. longipalpis throughout the year was driven by breeding site-related variables at the city scale, such as surface temperature and ground humidity, highlighting the importance of using lag data, both for modelling and surveillance, which once validated will provide enough time to perform a preventive intervention in the sites with higher abundances.

Abbreviations

- GLM:

-

Generalised linear model

- LST:

-

Land surface temperature

- NDVI:

-

Normalised difference vegetation index

- NDWI:

-

Normalised difference water index

- TRMM:

-

Tropical rainfall measuring mission

- VL:

-

Visceral leishmaniasis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Investing to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: third WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35671.

PAHO/WHO. Leishmaniasis: Informe Epidemiológico en las Américas. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2016.

Lainson R, Rangel EF. Lutzomyia longipalpis and the eco-epidemiology of American visceral leishmaniasis, with particular reference to Brazil: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100(8):811–27.

Salomon OD, Feliciangeli MD, Quintana MG, Afonso MM, Rangel EF. Lutzomyia longipalpis urbanisation and control. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(7):831–46.

Correa Antonialli SA, Torres TG, Paranhos Filho AC, Tolezano JE. Spatial analysis of American visceral leishmaniasis in Mato Grosso do Sul state, Central Brazil. J Inf Secur. 2007;54(5):509–14.

Botelho AC, Natal D. First epidemiological description of visceral leishmaniasis in Campo Grande, state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42(5):503–8.

Almeida PS, Sciamarelli A, Batista PM, Ferreira AD, Nascimento J, Raizer J, et al. Predicting the geographic distribution of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) and visceral leishmaniasis in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(8):992–6.

de Andrade AR, da Silva BA, Cristaldo G, de Andrade SM, Filho AC, Ribeiro A, et al. Spatial distribution and environmental factors associated to phlebotomine fauna in a border area of transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:260.

Leishmaniosis PMdSPyBSPNdCd. Manual de diagnóstico y tratamiento de las leishmaniosis. Asunción: Pan American Health Organization; 2011. p. 76.

Salud DGdVdl. Boletín Epidemiológico Semanal 2010–2015. Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social: Paraguay; 2016.

Canese A. Leishmaniosis visceral canina en el área metropolitana de la "Gran Asunción", Paraguay 2000. Medicina. 2000;60(Supl. III):65.

Torales M, Martínez N, Franco L. Variación estacional de Lutzomyia longipalpis. B° Kennedy - Lambaré. Rev Parag Epidemiol. 2010;1(1):36–41.

Salomon OD, Orellano PW. Lutzomyia longipalpis in Clorinda, Formosa province, an area of potential visceral leishmaniasis transmission in Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100(5):475–6.

Salomon O, Sinagra A, Nevot M, Barberian G, Paulin P, Estevez J, et al. First visceral leishmaniasis focus in Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(1):109–11.

Salomon OD, Basmajdian Y, Fernandez MS, Santini MS. Lutzomyia longipalpis in Uruguay: the first report and the potential of visceral leishmaniasis transmission. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(3):381–2.

Bravo AG, Quintana MG, Abril M, Salomon OD. The first record of Lutzomyia longipalpis in the Argentine northwest. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(8):1071–3.

Salomon OD, Quintana MG, Bruno MR, Quiriconi RV, Cabral V. Visceral leishmaniasis in border areas: clustered distribution of phlebotomine sand flies in Clorinda, Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(5):801–4.

Brazil RP, Caballero NN, Hamilton JG. Identification of the sex pheromone of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Asuncion, Paraguay. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2(1):51.

Casanova C, Colla-Jacques FE, Hamilton JG, Brazil RP, Shaw JJ. Distribution of Lutzomyia longipalpis chemotype populations in Sao Paulo state, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003620.

Cabrera AL: Regiones fitogeográficas Argentinas. In: Enciclopedia Argentina de Agricultura y Jardinería, vol. II, Buenos Aires edn. Buenos Aires: Editorial ACME SACI; 1976.

Espinosa MO, Polop F, Rotela CH, Abril M, Scavuzzo CM. Spatial pattern evolution of Aedes aegypti breeding sites in an Argentinean city without a dengue vector control programme. Geospat Health. 2016;11(3):471.

Dirección de Estadísticas CyD: CENSO 2010. Gobierno de la Provincia de Formosa; 2010.

Sudia WD, Chamberlain RW. Battery operated light trap, an improved model. Mosquito N. 1962;22:126–9.

Fernandez MS, Salomon OD, Cavia R, Perez AA, Acardi SA, Guccione JD. Lutzomyia longipalpis spatial distribution and association with environmental variables in an urban focus of visceral leishmaniasis, Misiones, Argentina. Acta Trop. 2010;114(2):81–7.

Galati EAB. Classificação de Phlebotominae. In: Rangel EF, Lainson R, editors. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rio do Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003. p. 23–51.

Marcondes CB. A proposal of generic and subgeneric abbreviations for Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) of the world. Entomol N. 2007;118:351–6.

Estallo EL, Luduena-Almeida FF, Visintin AM, Scavuzzo CM, Lanfri MA, Introini MV, et al. Effectiveness of NDWI (normalized difference water index) in Modelling Aedes aegypti house index. Int J Remote Sens. 2010;33:4254–65.

Estallo EL, Benitez EM, Lanfri MA, Scavuzzo CM, Almiron WR. MODIS environmental data to assess chikungunya, dengue and Zika diseases through Aedes (Stegomia) aegypti oviposition activity estimation. IEEE J Sel Topics Appl Earth Observ Remote Sens. 2016;99:1–6.

Gao BC. NDWI - a normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens Environ. 1996;58:257–66.

Wan Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Li ZL. Quality assessment and validation of the MODIS global land surface temperature. Int J Remote Sens. 2004;25:261–74.

Kummerow C, Barnes W, Kozu T, Shiue J, Simpson J. The tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) sensor package. J Atmos Ocean Technol. 1998;15:809–17.

Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Exploring the nature of covariate effects in the proportional hazards model. Biometrics. 1990;46(4):1005–16.

Austin M. Species distribution models and ecological theory: a critical assessment and some possible new approaches. Ecol Model. 2007;200(1):1-19.

Estallo EL, Lamfri MA, Scavuzzo CM, Almeida FF, Introini MV, Zaidenberg M, et al. Models for predicting Aedes aegypti larval indices based on satellite images and climatic variables. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008;24(3):368–76.

Estallo EL, Luduena-Almeida FF, Visintin AM, Scavuzzo CM, Lamfri MA, Introini MV, et al. Effectiveness of normalized difference water index in modelling Aedes aegypti house index. Int J Remote Sens. 2012;33(13):4254–65.

Espinosa-Montero J, Monterrubio-Flores EA, Sanchez-Estrada M, Buendia-Jimenez I, Lieberman HR, Allaert FA, et al. Development and validation of an instrument to evaluate perceived wellbeing associated with the ingestion of water: the water ingestion-related wellbeing instrument (WIRWI). PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158567.

Guisan A, Edwards TC, Hastie T. Generalized linear and generalized additive models in studies of species distributions: setting the scene. Ecol Model. 2002;157(2):89–100.

Duret JP. Notas sobre flebotómos argentinos. Rev Sanid Mil Argent. 1952;51:534–6.

Salomon OD, Sosa Estani S, Rossi GC, Spinelli GR. Presencia de Lutzomyia longipalpis y situación de la leishmaniosis visceral en Argentina. Medicina (B Aires). 2001;61(2):174–8.

de Oliveira AG, Falcao AL, Brazil RP. First record of finding Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) in the urban area of Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34(6):654–5.

Cousiño B. Vigilancia y control de la leishmaniasis en Paraguay. In: Consulta de Expertos OPS/OMS sobre Leishmaniasis Visceral en las Américas Informe Final. Rio de Janeiro: PANAFTOSA/Pan American Health Organization; 2006. p. 24–36.

Mestre GL, Fontes CJ. The spread of the visceral leishmaniasis epidemic in the state of Mato Grosso, 1998-2005. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40(1):42–8.

Santini MS, Fernandez MS, Perez AA, Sandoval AE, Salomon OD. Lutzomyia longipalpis abundance in the city of Posadas, northeastern Argentina: variations at different spatial scales. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(6):767–71.

Santini MS, Utges ME, Berrozpe P, Manteca Acosta M, Casas N, Heuer P, et al. Lutzomyia longipalpis presence and abundance distribution at different micro-spatial scales in an urban scenario. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(8):e0003951.

Figueiredo HR, Santos MF, Casaril AE, Infran JO, Ribeiro LM, Fernandes CE, et al. Sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in an endemic area of leishmaniasis in Aquidauana municipality, Pantanal of Mato Grosso Do Sul, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2016;58:87.

Fernandez MS, Santini MS, Cavia R, Sandoval AE, Perez AA, Acardi S, et al. Spatial and temporal changes in Lutzomyia longipalpis abundance, a Leishmania infantum vector in an urban area in northeastern Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(7):817–24.

Liang S. An optimization algorithm for separating land surface temperature and emissivity from multispectral thermal infrared imagery. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2001;39(2):264–74.

Peres LF, DaCamara CC. Land surface temperature and emissivity estimation based on the two-temperature method: sensitivity analysis using simulated MSG/SEVIRI data. Remote Sens Environ. 2004;91(3):377–89.

Pinheiro AC, Privette JL, Mahoney R, Tucker CJ. Directional effects in a daily AVHRR land surface temperature dataset over Africa. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2004;42(9):1941–54.

Wan Z, Dozier J. A generalized split-window algorithm for retrieving land-surface temperature from space. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 1996;34(4):892–905.

Wan Z. MODIS land-surface temperature algorithm theoretical basis document (LST ATBD). Santa Barbara: Institute of Computational Earth System Science; 1999. p. 75.

Feliciangeli MD. Natural breeding places of phlebotomine sandflies. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18(1):71–80.

Quintana M, Salomon O. Guerra R, De Grosso ML, Fuenzalida A. Phlebotominae of epidemiological importance in cutaneous leishmaniasis in nothwestern Argentina: risk maps and ecological niche models. Med Vet Entomol 2013;27:1:39-48.

Acknowledgements

We thank all field workers who made the entomological samplings and residents of Clorinda City who allowed the installation of traps in their houses. We also thank Ignacio Gould for the taxonomic identification of the phlebotomine. Authors wish to thank Victoria Periago for her help in the proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

Mundo Sano Foundation provided the funding for the design of this study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AGB, AG, MA, MS and ODS contributed to the design of the study; AGB and AG analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. MA, MS and ODS contributed to the analysis and critical review. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez-Bravo, A., German, A., Abril, M. et al. Spatial population dynamics and temporal analysis of the distribution of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the city of Clorinda, Formosa, Argentina. Parasites Vectors 10, 352 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2296-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2296-0