Abstract

Background

Genotyping malaria parasites to assess their diversity in different geographic settings have become necessary for the selection of antigenic epitopes for vaccine development and for antimalarial drug efficacy or resistance investigations. This study describes the genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from uncomplicated malaria cases over a ten year period (2003–2013) in Ghana using the polymorphic antigenic marker, merozoite surface protein 2 (msp2).

Methods

Archived filter paper blood blots from children aged nine years and below with uncomplicated malaria collected from nine sites in Ghana were typed for the presence of the markers. A total of 880 samples were genotyped for msp2 for the two major allelic families, FC27 and 3D7, using nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The allele frequencies and the multiplicity of infection were determined for the nine sites for five time points over a period of ten years, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2010 and 2012–2013 malaria transmission seasons.

Results

The number of different alleles detected for the msp2 gene by resolving PCR products on agarose gels was 14. Both of the major allelic families, 3D7 and FC27 were common in all population samples. The highest multiplicity of infection (MOI) was observed in isolates from Begoro (forest zone, rural site): 3.31 for the time point 2007–2008. A significant variation was observed among the sites in the MOIs detected per infection (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.001) for the 2007 isolates and also at each of the three sites with data for three different years, Hohoe, P = 0.03; Navrongo, P < 0.001; Cape Coast, P < 0.001. Overall, there was no significant difference between the MOIs of the three ecological zones over the years (P = 0.37) and between the time points when data from all sites were pooled (P = 0.40).

Conclusions

The diversity and variation between isolates detected using the msp2 gene in Ghanaian isolates were observed to be profound; however, there was homogeneity throughout the three ecological zones studied. This is indicative of gene flow between the parasite populations across the country probably due to human population movements (HPM).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria parasite genetic diversity creates a great hindrance to vaccine development efforts and enhances antimalarial drug resistance. Genetic diversity occurs as a result of genetic recombinations from numerous allelic polymorphisms exhibited at various genetic loci and also through diversifying selection by immunity [1, 2]. It has been shown to be comparatively high in hyper-endemic areas than in low endemic areas [1, 2]. The level of antigenic diversity resulting in the multiplicity of infections varies from one malaria endemic region to another and even between countries. Such that the variant forms of the parasite exist at different frequencies in different geographic areas presenting different complexities of infection [3]. Parasite genetic diversity has been implicated in evolutionary fitness and consequently populations with high diversity have the ability to survive against ongoing interventions in malaria endemic areas thereby frustrating control efforts [4, 5].

The merozoite surface proteins 2 (msp2) is a polymorphic antigenic marker that has been used extensively to describe the diversity of parasite populations in many malaria endemic countries. Msp2 gene has two major allelic families, FC27 and ICI/3D7 based on the variable non-repeat sequences as well as the varying sizes of the tandem repeats in the central region [6, 7]. This parasite surface antigen plays a role in parasite invasion of the erythrocytes and due to the high polymorphism they exhibit, the parasite gains the ability to evade immune responses [8, 9]. Of the three marker genes, msp1, msp2 and glutamine-rich protein (glurp), which have been endorsed by the WHO for use in distinguishing between recrudescence and new infection in recurrent infections during antimalarial drug efficacy investigations, the msp2 marker is the most polymorphic and therefore the highest discriminatory and informative marker [9–13].

Ghana is a malaria endemic country with three different ecological zones with either perennial or seasonal transmission of malaria. The northern part of the country has Guinea savannah ecology, middle belt has forest ecology and the southern part has coastal savannah ecology. Seasonal transmission is observed in the northern part whilst the forest and the coastal savannah experiences perennial transmission. The vectors of transmission vary per the ecological zones such that Anopheles gambiae (sensu stricto) transmits the parasite in all 3 ecological zones, A. melas transmit in the coastal savannah zone, A. arabiensis and A. funestus (s.s.) transmits mostly in the Guinea savannah zone of the country. Transmission intensities are high with peaks observed during the wet season. Malaria accounted for 44 % of all outpatient clinic visits in 2013 and 22.3 % of all under-five deaths in Ghana [14]. The main control strategy is active case detection and treatment using artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Other interventions include intermittent preventive treatment among pregnant women (IPTp), seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), long lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), and indoor residual spraying (IRS) [15].

Information on the diversity of malaria parasites in Ghana is scanty and in the search for an effective vaccine for the African malaria endemic region it is crucial to describe genetically, the parasite population structure over the years. This study therefore determined the genetic diversity of parasites in the country by detecting the presence of msp2 alleles in P. falciparum isolates from uncomplicated malaria cases collected over ten years (2003–2013) from nine sentinel sites for monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy/resistance in Ghana. Findings from this study will serve as baseline data for future studies on parasite population structure and antimalarial drug resistance surveillance in the country.

Methods

Study sites

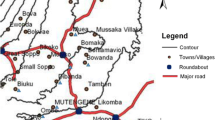

The archived samples used for this study were collected in 2003–2013 from nine out of the ten sentinel sites set up by the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) for monitoring antimalarial drug resistance in the country. The description of these sites has already been published [16–22]. These sites were categorised into three ecological zones and urbanicity: Navrongo (rural; 10.9840°N, 1.0921°W), Wa (rural; 10.0601°N, 2.5099°W) and Yendi (rural; 9.4450°N, 0.0093°W) in the guinea savanna with seasonal malaria transmission; Begoro (rural; 6.3916°N, 0.3795°W), Bekwai (rural; 6.4532°N, 1.5838°W), Hohoe (urban; 7.1519°N, 0.4738°E), Sunyani (urban; 7.3349°N, 2.3123°W) and Tarkwa (urban; 5.3018°N, 1.9930°W) in the tropical forest with perennial malaria transmission; Cape-Coast (urban; 5.1315°N, 1.2795°W) in the coastal savanna with perennial malaria transmission. A map of Ghana indicating the sites is shown in Fig. 1.

A map of Ghana showing the ten sentinel sites for monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy/resistance in the country. These sites are located in the three ecological zones of Ghana and were set up by a joint collaboration between Noguchi Memorail Institute fo Medical Research (NMIMR) and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP). Abbreviations: R, rural setting; U, urban setting

Study samples

Archived filter paper blood blots collected from children aged nine years and below with uncomplicated malaria from antimalarial drug resistance surveillance studies conducted in 2003 to 2013 and stored at room temperature were used [16–22]. These samples were collected after the parents or guardians of these children gave informed consent for their participation in the studies. Ethical approval for the study was given by the NMIMR IRB.

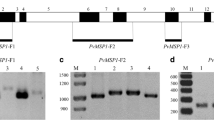

Detection of Plasmodium species and msp2 alleles by PCR

Parasite DNA from 880 filter paper blood blot samples was extracted using Qiagen DNA Blood Minikit (Qiagen, California USA). Parasite species detection using nested PCR was done following published protocols with minimal changes [23, 24]. Nested PCR was used for the detection of msp2 alleles following recommended standardised protocols from the Worldwide Antimicrobial Resistance Network (WWARN) and World Health Organization (WHO) for the identification of parasite populations [10–12]. The primers for both primary and nested PCRs for the detection of the alleles of the msp2 gene are from previously published protocols [10–12] (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Data analysis

Sensitivity of PCR was determined from the number of PCR positives over the total number of samples analysed. Frequencies of alleles of the genes were determined for each sample by individual counts of PCR positivity. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) defined as the mean number of genotypes per infection was determined as the quotient of the total number of alleles per locus over the total number of PCR positive samples per locus. Differences in the MOI between time points and the ecological zones were determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) whilst a difference in MOIs between the sites per time point was determined using Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

A total of 880 samples from nine sites were typed for msp2 alleles, FC27 and 3D7 for five different time points. Of the 880 samples analysed, 52 (6 %) were from 2003 to 2004, 209 (24 %) from 2005 to 2006, 372 (42 %) from 2007 to 2008, 89 (10 %) from 2010 to 158 (18 %) from 2012 to 2013. The contribution from each site to the total number of samples is shown in Table 1. The sensitivity of the PCR method for the typing of the alleles of msp2 ranged from 46 to 100 %. It was observed that sensitivity was comparatively higher in the most recently collected samples 2007–2013. Therefore, data analysis was conducted with 711 PCR positive samples, 37 from 2003 to 2004, 136 from 2005 to 2006, 332 from 2007 to 2008, 73 from 2010 to 133 from 2012 to 2013 (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Allele frequencies for msp2

Fourteen different alleles were detected for msp2 gene by analysis of PCR products on agarose gels. The most frequent allele sizes which persisted in all the three ecological zones within the periods were FC27-400 and 3D7-600. All the genotypes in each isolate are shown in full in Additional file 3: Tables S3-S7). There was no significant difference between the allele frequencies of FC27 and 3D7 over the years and the trend analysis of allele frequencies was also not significant (χ 2 = 2.484, df = 1, P = 0.115).

Multiplicity of infection (MOI)

The MOI defined as the mean number of genotypes per infection (Table 2) for each locus per time point was determined for every site, and geometric mean MOIs were computed for the different ecological zones and for the country (Table 2). The highest MOI was 3.31 in Begoro (forest zone) in 2007–2008 (Table 2). The geometric mean MOIs for all the ecological zones per time point are shown in Table 3. The MOIs ranged between 1.07–2.82, 1.40–3.31 and 1.13–2.03, respectively for Guinea savannah, forest and coastal savannah zones for all the time points. No significant difference was observed between the geometric mean MOIs of the ecological zones (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.370) and between the five time points when the data was pooled (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.405). Except for the isolates from 2007 which showed a significant variation among the sites in the distributions of numbers of alleles of msp2 detected per infection (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). There was also significant variation in the MOI across the years for three sites with data for three years using Fisher’s exact test; Hohoe, P = 0.03; Navrongo, P < 0.001; Cape Coast, P < 0.001 (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The parasite population structure of P. falciparum isolates from Ghana was determined using the diversity in the msp2 gene over a decade. This genetic marker is recommended for genotyping parasites in antimalarial drug efficacy trials and parasite population structure analysis by the WHO [10–12]. The samples used in this investigation were collected from all the regions of Ghana which also represent the three distinct ecological zones in the country. The findings from this study revealed a high level of genetic diversity within the msp2 gene, however there was lack of major differences in parasite variants across the country which may be as a result of a high level of gene flow due to human population movements (HPM) over the years. A recent genome-wide sequences analysis of isolates from two ecologically distinct areas in Ghana also showed the genetic structure of parasite populations as very similar [25]. The number of genotypes was 14 and 3D7 was the predominant allele from 2005 to 2010. Generally, the determined MOIs between ecological zones at the different time points and overall was not significant except for the 2007 isolates where a significant difference was observed among the nine sites.

Msp2 block 3 is known to have a higher polymorphism and therefore provides very useful information in describing the diversity of parasites in a population compared to msp1 and glurp [9, 13]. The study showed high polymorphism msp2 gene and the predominant allelic genotypes detected had low to high frequencies which fluctuated at the different time points. This observation of predominant alleles is due to genetic recombinations that result in parasites with particular alleles having high frequencies and consequently a high level of biological fitness [26]. These findings are similar to observations made in Myanmar on the genetic diversity at the same locus and the observed fluctuations in allele frequencies of these predominant alleles over the years were attributed to selection by the hosts’ immune responses [27]. These immune responses are known to be strain-specific against recurrent parasites with same allelic antigens resulting in the differences in the prevalence of specific genotypes over time [27]. Of the two allelic families of the msp2 gene, 3D7 was the predominant allele and this observation has also been made in several African and Southeast Asian countries [4, 9, 28–38]. Another report from Agyeman-Budu and colleagues who investigated parasite diversity in asymptomatic infections in the forest belt area of Ghana (Kintampo), showed a predominance of 3D7 over FC27 at a ratio of 4:1 in the dry season [39]. It is evident the 3D7 allelic family is the predominant msp2 allele in high disease transmission areas.

There was generally no significant difference in the MOIs between the different ecological zones and also between time points when data were pooled; however, for the isolates from nine sites in 2007 showed variability in the MOIs. Although the population frequencies of the two msp2 alleles (FC27 and 3D7) did not vary significantly among the nine populations in 2007 as a result of each local population having similarly wide spectrum of genotypes variation within each of these major types, the observed variation in MOIs estimates could not be due to differences in msp2 allelic diversity locally (DJ Conway, personal communication). Whole genome sequence analyses show that parasite populations in different parts of West Africa have very similar genetic diversity [26, 40], and a comparison of different areas in Ghana has also shown that allele frequency distributions are very similar throughout the genome [25]. As these populations are well connected geographically, there is unlikely to be significant local divergence in allele frequencies of any parasite gene unless there have been significant differences in selection operating locally, as may be the case for drug resistance genes [17, 18]. It is known that the lack of differences between allele frequencies over time in a population is indicative of frequency equilibrium due to absence of selection which is controlled by frequency-dependent immune selection [41, 42]. This lack of significant variation in allele frequencies of msp2 alleles as observed in our study over time has also been observed in parasite populations from the Gambia and Brazil [41, 43, 44].

The observation of lack of differences in parasite variants in all three ecological zones may be due to HPM across the country. For people living in the Guinea savannah ecological zone with seasonal transmission, during the dry season which could last for about 6 months, they become migrant workers who move to perennial transmission areas for economic reasons and return to farm their lands before the rains begin. As such they are carriers of parasites from their ecological zone to other zones and also carry parasites of the other zones back to their areas. HPM between rural and urban areas is the norm in the country for trading purposes and for visiting extended families which is an important cultural practice. Therefore, HPM greatly enhances the movement of parasite variants from one place to another which results in variants with minor differences in alleles of the msp2 gene investigated across the country. The implication of the observed level of genetic diversity in parasite populations in high transmission areas as a result of genetic recombination poses a threat to the identification of antigenic epitopes for malaria vaccine design. Although extensive genetic diversity is a hindrance to vaccine development efforts, for people living in endemic areas, such diversity enhances the encounter with diverse parasite clones which in turn, help with the natural acquisition of immune responses against the multiple clones of the parasite and subsequent protection against disease symptoms.

Sequencing the polymorphic regions and microsatellite typing of the genetic locus investigated could provide deeper insight into the variations in gene sequences as detected by other studies [27, 29, 45], and therefore further analyses are ongoing which involves sequencing and microsatellite typing to reveal the genetic complexity of circulating parasites in Ghana.

Conclusion

There was an immense genetic diversity in the parasite population in Ghana upon investigating the msp2 gene. However, there was minimal variation or homogeneity in parasite populations across the country which may be due to gene flow from the effect of human population movements.

Abbreviations

ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; ANOVA, analysis of variance; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; glurp, glutamine rich protein; HPM, human population movements; IPTp, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy; IRB, institutional review board; IRS, indoor residual spraying; LLINS, long lasting insecticide-treated nets; MOI, multiplicity of infection; msp1&2, merozoite surface proteins 1 and 2; NMCP, national malaria control programme; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SMC, seasonal malaria chemoprevention; WHO, World Health Organization; WWARN, worldwide antimicrobial resistance network

References

Hoffmann EH, da Silva LA, Tonhosolo R, Pereira FJ, Ribeiro WL, Tonon AP, et al. Geographical patterns of allelic diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum malaria-vaccine candidate, merozoite surface protein-2. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:117–32.

Paul RE, Hackford I, Brockman A, Muller-Graf C, Price R, Luxemburger C, White NJ, Nosten F, Day KP. Transmission intensity and Plasmodium falciparum diversity on the northwestern border of Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:195–203.

Raj DK, Das RB, Dash AP, Supakar PC. Genetic diversity in the merozoite surface protein 1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum in different malaria-endemic localities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(3):285–9.

Barry AE, Schultz L, Senn N, Nale J, Kiniboro B, Siba PM, et al. High levels of genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum populations in Papua New Guinea despite variable infection prevalence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88(4):718–25.

Dhafer R. Correlation between fitness and diversity. Conserv Ecology. 2003;17:231–7.

Fenton B, Clark JT, Khan CMA, Robinson JV, Walliker D, Ridley R, et al. Structural and antigenic polymorphisms of the 38- to 45-kilodalton merozoite surface antigen (MSA-2) of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:963–71.

Smythe JA, Coppel RL, Day KP, Martin RK, Oduola AMJ, Kemp DJ, Anders RF. Structural diversity in the Plasmodium faciparum merozoite surface antigen 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1751–5.

Eisen D, Billman-Jacobs H, Marshall VF, Dave F, Coppel F. Temporal variation of the merozoite surface protein 2 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Am Soc Microbiol. 2003;66:239–46.

Kidima W, Nkwengulila G. Plasmodium falciparum msp2 genotypes and multiplicity of infections among children under five years with uncomplicated malaria in Kibaha, Tanzania. J Parasitol Res. 2015;2015:1–6.

WHO. Recommended Genotyping Procedures (RGPs) to identify parasite populations. Amsterdam: Medicines for Malaria Venture and World Health Organization. www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/rgptext_stipdf 2007. Accessed 2 Jun 2014.

WWARN. Molecular Testing for Malaria: Overview of Standards. www.wwarn.org/sites/default/files/PCR 2007. Accessed 2 Jun 2014.

WHO. Methods and techniques for clinical trials on antimalarial drug efficacy: genotyping to identify parasite populations:informal consultation organized by the Medicines for Malaria Venture and cosponsored by the World Health Organization, 29–31 May 2007. Amsterdam: WHO; 2007.

Felger I, Tavul L, Kabintik S, Marshall V, Genton B, Alpers M, Beck H-P. Plasmodium falciparum: extensive polymorphism in meroziote surface antigen 2 alleles in an area with endemic malaria in Papua New Guinea. Exper Biol. 1994;79(2):106–16.

MOH. Ministry of Health, Ghana: National Malaria Control Programme 2013 Annual Report. 2013.

MOH. Ministry of Health: Strategic Plan for Malaria Control in Ghana 2014 – 2020. 2014.

Abuaku B, Duah N, Quaye L, Quashie N, Koram K. Therapeutic efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine combination in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria among children under five years of age in three ecological zones in Ghana. Malar J. 2012;11:388.

Duah NO, Matrevi SA, de Souza DK, Binnah DD, Tamakloe MM, Opoku VS, et al. Increased pfmdr1 gene copy number and the decline in pfcrt and pfmdr1 resistance alleles in Ghanaian Plasmodium falciparum isolates after the change of anti-malarial drug treatment policy. Malar J. 2013;12:377.

Duah NO, Quashie NB, Abuaku BK, Sebeny PJ, Kronmann KC, Koram KA. Surveillance of molecular markers of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine 5 years after the change of malaria treatment policy in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(6):996–1003.

Duah NO, Wilson MD, Ghansah A, Abuaku B, Edoh D, Quashie NB, Koram KA. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and multidrug resistance genes, and treatment outcomes in Ghanaian children with uncomplicated malaria. J Trop Pediat. 2007;53(1):27–31.

Koram KA, Abuaku B, Duah N, Quashie N. Comparative efficacy of antimalarial drugs including ACTs in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria among children under 5 years in Ghana. Acta Trop. 2005;95(3):194–203.

Quashie NB, Duah NO, Abuaku B, Koram KA. The in-vitro susceptibilities of Ghanaian Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarial drugs. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101(5):391–8.

Quashie NB, Duah NO, Abuaku B, Quaye L, Ayanful-Torgby R, Akwoviah GA, et al. A SYBR Green 1-based in vitro test of susceptibility of Ghanaian Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates to a panel of anti-malarial drugs. Malar J. 2013;12:450.

Nsobya SL, Parikh S, Kironde F, Lubega G, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Molecular evaluation of natural history of asymptomatic parasitemia in Ugandan children. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(12):2220–6.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, et al. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61(2):315–20.

Duffy CW, Assefa SA, Abugri J, Amoako N, Owusu-Agyei S, Anyorigiya T, et al. Comparison of genomic signatures of selection on Plasmodium falciparum between different regions of a country with high malaria endemicity. BMC Genom. 2015;16:257.

Miotto O, Almagro-Garcia J, Manske M, Macinnis B, Campino S, Rockett K, et al. Multiple populations of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Cambodia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):648–55.

Yuan L, Zhao H, Wi L, Li X, Parker D, Xu S, et al. Plasmodium falciparum populations from northeastern Myanmar display high levels of genetic diversity at multiple antigneic loci. Acta Trop. 2013;125:53–9.

Ibara-Okabande R, Koukouikila-Koussounda F, Ndounga M, Vouvoungui J, Malonga V, Casimiro PN, et al. Reduction of multiplicity of infections but no change in msp2 genetic diversity in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Congolese children after introduction of artemisinin-combination therapy. Malar J. 2012;11:410.

Mwingira K, Nkwengulila G, Schoepflin S, Sumari D, Beck H-P, Snounou G, et al. Plasmodium falciparum msp1, msp2 and glurp allele frequency and diversity in subSaharan Africa. Malar J. 2011;10:79.

Congpuong K, Sukaram R, Prompan Y, Dornae A. Genetic diversity of the msp-1, msp-2, and glurp genes of Plasmodium falciparum isolates along the Thai-Myanmar borders. As Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(8):598–602.

Niang M, Loucoubar C, Sow A, Diagne MM, Faye O, Faye O, et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from concurrent malaria and arbovirus co-infections in Kedougou, southeastern Senegal. Malar J. 2016;15:155.

Razak MRMA, Sastu UM, Norahmad NA, Abdul-Karim A, Muhammad A, Munlandy PK, et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum populations in malaria declining areas of Sabah, East Malaysia. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152415.

Gosi P, Lanteri CA, Tyner SD, Se Y, Lon C, Spring M, et al. Evaluation pf parasite subpopulations and genetic diversity of msp1, msp2 and glurp genes during and following artesunate monotherapy treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Western Cambodia. Malar J. 2013;12:403.

Basco LK, Tahar R, Escalante A. Molecular epidemiology of malaria in Cameroon. XVIII. Polymorphisms of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen-2 gene in isolates from symptomatic patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:238–44.

Ghanchi NK, Mårtensson A, Ursing J, Jafri S, Bereczky S, Hussain R, Beg MA. Genetic diversity among Plasmodium falciparum field isolates in Pakistan measured with PCR genotyping of the merozoite surface protein 1 and 2. Malar J. 2010;9:1.

Snounou G, Zhu X, Siripoon N, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN, Viriyakosol S. Biased distribution of msp1 and msp2 allelic variants in Plasmodium falciparum populations in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93(4):369–74.

Zakeri S, Bereczky S, Naimi P, Pedro GJ, Djadid ND, Färnert A, et al. Multiple genotypes of the merozoite surface proteins 1 and 2 in Plasmodium falciparum infections in a hypoendemic area in Iran. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1060–4.

Kang J-M, Moon S-U, Kim J-Y, Cho S-H, Lin K, Sohn W-M, et al. Genetic polymorphism of merozoite surface protein-1 and merozoite surface protein-2 in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Myanmar. Malar J. 2010;9:131.

Agyeman-Budu A, Brown C, Adjei G, Adams M, Dosoo D, Dery D, et al. Trends in multiplicity of Plasmodium falciparum infections among asymptomatic residents in the middle belt of Ghana. Malar J. 2013;12:22.

Mobegi VA, Duffy CW, Amambua-Ngwa A, Loua KM, Lama EM, Nwakanma DC, et al. Genome-wide analysis of selection on the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in West African populations of differing infection endemicity. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31(6):1490–9.

Conway DJ, Greenwood BM, McBride JS. Longitudinal study of Plasmodium falciparum polymorphic antigens in a malaria-endemic population. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1122–7.

Eisen D, Billman-Jacobe H, Marshall VF, Fryau D, Coppel RL. Temporal variation of the merozoite surface protein-2 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1998;66:239–46.

Orjuela-Sánchez P, Da Silva-Nunes M, Da Silva NS, Scopel KKG, Gonçalves RM, Malafronte RS, Ferreira MU. Population dynamics of genetically diverse Plasmodium falciparum lineages: community-based prospective study in rural Amazonia. Parasitology. 2009;136(10):1097–105.

Sallenave-Sales S, Ferreira-da-Cruz MF, Faria CP, Cerruti CJ, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, Zalis MG. Plasmodium falciparum: limited genetic diversity of MSP-2 in isolates circulating in Brazilian endemic areas. Exper Parasitol. 2003;103:127–35.

Atroosh WM, Al-Mekhlafi H, Mahdy MAK, Saif-Ali R, Al-Mekhlafi AM, Srin J. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Pahang, Malaysia based on MSP-1 and MSP-2 genes. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:233.

Acknowledgement

This work which includes the collection of the samples used in this study was funded by the WHO/Multilateral Initiative in Malaria (MIM) [Project no. 980034], the Global Fund to fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM)/National Malaria Control Programme, the Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System (GEIS), a Division of the US Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC) [Project no. C0437_11_N3] and the European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP)-West African Network of Excellence for Clinical Trials in TB, AIDS and Malaria (WANETAM) (Project code CB.07.41700.007). The laboratory assistance received from Miss Christiana Onwona, Mr. Edem Akoto and Mr. John Mevemeo is highly appreciated. The valued assistance from Professor David Conway on data analysis and discussion is thereby acknowledged. The authors wish to thank the Director of NMIMR, Professor Kwadwo Koram, for his permission to publish this article.

Funding

1. Multilateral Initiative in Malaria-WHO/TDR (Project number: 980034). 2. Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System GEIS), a Division of the US Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC) (Project number: C0437_11_N3). 3. European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP)/West African Network of Excellence for Clinical Trials in TB, AIDS and Malaria (WANETAM) (Project number: CB.07.41700.007). 4. Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM)/National Malaria Control Programme. The funding agencies stated above did not play a role in the design of the study, collection of samples, analysis and interpretation of data as well as in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Raw data from which the conclusions of the manuscript rely are available as Additional file 3: Tables S3–S7.

Authors’ contributions

NOD, NBQ, BA and KAK conceived and designed the study. NOD and SM did the laboratory analysis of samples to generate molecular data. NOD and BA conducted the data analysis. NOD drafted the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the study was given by the NMIMR IRB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primer names and sequences for the detection of msp2 alleles. (DOC 31 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Variation in genotypic mixedness of Plasmodium falciparum infections at the nine sites at different time points. (DOC 66 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Allele sizes and number of genotypes per infection for isolates collected in 2003–2004. (XLS 87 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Duah, N.O., Matrevi, S.A., Quashie, N.B. et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from uncomplicated malaria cases in Ghana over a decade. Parasites Vectors 9, 416 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1692-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1692-1