Abstract

Background

Enterocytozoon bieneusi is a common opportunistic pathogen that is widely detected in humans, domestic animals and wildlife, and poses a challenge to public health. The present study was performed to evaluate the prevalence, genotypic diversity and zoonotic potential of E. bieneusi among wildlife at Chengdu and Bifengxia zoological gardens in Sichuan Province, China.

Results

Of the 272 fresh fecal samples harvested from 70 captive wildlife species at Chengdu Zoo (n = 198) and Bifengxia Zoo (n = 74), 21 (10.6 %) and 22 (29.7 %) tested positive for E. bieneusi by internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing analysis, respectively. Specifically, genotypes D, Peru 6, CHB1, BEB6, CHS9, SC02 and SC03, and genotypes D, CHB1, SC01 and SC02 were detected in the Chengdu and Bifengxia Zoo samples, respectively. Five known genotypes (D, Peru 6, BEB6, CHS9 and CHB1) and three novel genotypes (SC01, SC02 and SC03) were clustered into the zoonotic group (group 1) and host-adapted group (group 2). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis targeting three microsatellites (MS1, MS3 and MS7) and one minisatellite (MS4) were successfully sequenced for 37, 33, 35 and 37 specimens, generating 8, 3, 11 and 15 distinct locus types, respectively. Altogether, we identified 27 multilocus genotypes (MLGs) among the E. bieneusi isolates by MLST. These data highlight the high genetic diversity of E. bieneusi among zoo wildlife.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the prevalence and genotypic diversity of E. bieneusi infections among captive wildlife in zoos in southwest China. Notably, we identified three novel E. bieneusi genotypes, as well as six new mammalian hosts (Asian golden cats, Tibetian blue bears, blackbucks, hog deer, Malayan sun bears and brown bears) for this organism. Moreover, the occurrence of zoonotic genotypes suggests that wildlife may act as reservoirs of E. bieneusi that can serve as a source of human microsporidiosis. The findings presented here should contribute to the control of zoonotic disease in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Microsporidia, classified as fungi, are the causative agents of microsporidiosis, an important emerging infectious disease [1, 2]. Among the approximately 1,300 microsporidian species identified, Enterocytozoon bieneusi is the most frequent cause of microsporidial infections in humans [3]. Enterocytozoon bieneusi is an obligate intracellular pathogen that is widely distributed in a variety of animals, including domestic animals and wildlife, and can also be found in water and contaminated food [4–8]. Enterocytozoon bieneusi colonizes the epithelium of the small intestine, localizing predominantly within the apical portion of the villus [9]. While microsporidiosis is typically associated with self-limiting diarrhea among healthy individuals, immunocompromised patients, particularly those suffering from AIDS, can develop life-threatening chronic diarrhea [10–13].

Due to the small size of its spores and the uncharacteristic staining properties of this organism, it is difficult to detect E. bieneusi by light microscopy [5]. As a result, molecular methods, particularly PCR-based amplification of E. bieneusi-specific sequences, are primarily utilized to detect and confirm E. bieneusi infections [6]. Currently, due to the high degree of diversity observed among E. bieneusi isolates, amplification and sequencing of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) is widely used to identify and genotype these strains [14]. To date, over 200 E. bieneusi genotypes, clustered into eight groups (Group 1–8), have been defined [15, 16]. While the strains comprising Group 1 have been isolated from both animals and humans and are generally associated with a major zoonotic potential, those of the other groups are considered host-adapted, as they exhibit a narrow host-range and possess little to no zoonotic potential; however, these organisms remain a potential public health concern [15, 17].

A wide variety of wildlife species are housed at Bifengxia Zoo and Chengdu Zoo. Indeed, Chengdu Zoo is one of the largest zoos in southwest China. Zoo animals are considered domesticated in that they have been separated from their natural habitat. Furthermore, they live under unnatural conditions and in higher densities than those observed in nature [18]. Previous studies have found Cryptosporidium andersoni in Bactrian camels and zoonotic Cryptosporidium at Bifengxia Zoo [19, 20]. To protect the health of wildlife and to avoid potential public health risks, it is necessary to investigate the occurrence of E. bieneusi in captive wild animals. The aim of this study was to examine the prevalence of E. bieneusi in various wild animal species in Bifengxia Zoo and Chengdu Zoo, and to genotype the resulting E. bieneusi isolates via ITS sequencing and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analyses. Furthermore, we assessed the zoonotic potential of each E. bieneusi strain isolated.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

A total of 272 fecal samples were obtained from wildlife in Chengdu Zoo (n = 198) and Bifengxia Zoo (n = 74), which are located in Chengdu and Ya’an, respectively, in Sichuan Provence, China, between June 2014 and September 2015. All samples were placed on ice in separate containers, and transported to the laboratory immediately. Prior to use, specimens were stored in 2.5 % potassium dichromate at 4 °C in a refrigerator.

Fecal samples were washed with distilled water and centrifuge at 3,000× g for three min. This process was repeated in triplicate. Genomic DNA was then extracted from approximately 200 mg of each semi-purified product using an E.Z.N.A.® Tool DNA Kit (D4015–02; Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA samples were stored in 200 μl of the kit Solution Buffer at -20 °C until use.

Nested PCR amplification and sequencing

Enterocytozoon bieneusi was identified by nested PCR amplification of the ITS gene. Multilocus genotyping (MLGs) of ITS-positive specimens was achieved by amplifying three microsatellites (MS1, MS3 and MS7) and one minisatellite (MS4). The primers and amplification conditions for these reactions were as previously described (Table 1) [21, 22]. Each reaction included 12.5 μl 2× Taq PCR Master Mix (KT201-02; Tiangen, Beijing, China), 7.5 μl deionized water (Tiangen), 1 μl 0.1 % bovine serum albumin (BSA; TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan), 2 μl DNA for the primary PCR or primary PCR products 2 μl for the secondary PCR amplification. Secondary PCR products were subjected to 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with Golden View. Products of the expected size (392 bp, 675 bp, 537 bp, 885 bp, and 471 bp for ITS, MS1, MS3, MS4 and MS7, respectively) were sent to Invitrogen (Shanghai, China) for two-directional sequencing analysis.

Phylogenetic analyses

All nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were aligned with E. bieneusi reference sequences downloaded from the GenBank database using Blast [23] and ClustalX software [24]. Phylogenetic analysis of ITS sequences was performed using Mega software [25], and Maximum Likelihood analysis of the aligned E. bieneusi sequences was utilized to support genotype classifications. A total of 1,000 replicates were used for bootstrap analysis.

Nucleotide sequence GenBank accession numbers

The representative nucleotide sequences for the ITS regions of strains isolated from northern white-cheeked gibbons (Nomascus leucogenys), olive baboons (Papio anubis), northern raccoons (Procyon lotor), golden snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana), African lions (Panthera leo), Asiatic golden cats (Catopuma temminckii), giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus), Tibetian blue bears (Ursus arctos pruinosus), sika deers (Cervus nippon), red pandas (Ailurus fulgens), Malayan sun bears (Helarctos malayanus), brown bears (Ursus arctos), ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta), alpacas (Lama pacos), blackbucks (Antilope cervicapra) and hog deers (Axis porcinus) were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KU852462–KU852485 and KX423961. All MS1, MS3, MS4 and MS7 nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KU871860–KU871896, KU871897–KU871930, KU871931–KU871965 and KU871966–KU872002, respectively.

Results

Prevalence of E. bieneusi

In total, 43 of the 272 (15.8 %) animals sampled in this study were infected with E. bieneusi. Specifically, 21 of the 198 (10.6 %) and 22 of the 74 (29.7 %) animals sampled from Chengdu and Bifengxia Zoo were E. bieneusi-positive, respectively. At Chengdu Zoo, eight (4.0 %), nine (4.5 %), and four (2.0 %) fecal samples from animals of the orders Carnivora, Artiodactyla and Primates were positive for E. bieneusi, respectively. At Bifengxia Zoo, 20 (27.0 %) and two (2.7 %) samples from animals of the orders Carnivora and Primates, respectively, contained E. bieneusi (Additional file 1: Table S1; Additional file 2: Table S2).

Genotypes of E. bieneusi strains and phylogenetic analysis

In the present study, eight E. bieneusi genotypes, comprising five known genotypes (D, Peru 6, BEB6, CHS9, CHB1) and three novel genotypes (SC01, SC02, SC03) were identified by ITS sequencing analysis. Genotype D was detected in an Asiatic golden cat (n = 1), African lions (n = 2), golden snub-nosed monkeys (n = 2), olive baboons (n = 2), a northern raccoon (n = 1), and a northern white-cheeked gibbon (n = 1). Genotype Peru 6 was isolated from a single giant panda (n = 1); genotype BEB6 was isolated from a red deer (n = 1), hog deer (n = 2), an alpaca (n = 1), and a sika deer (n = 1) and genotype CHS9 was isolated from a blackbuck (n = 1) and a hog deer (n = 1). Notably, CHB1 was primarily found in Asiatic black bears (n = 9), but was also detected in a Malayan sun bear (n = 1), a Tibetian blue bear (n = 1), a ring-tailed lemur (n = 1), a brown bear (n = 1) and in red pandas (n = 2). Lastly, in regard to the novel genotypes detected, strain SC01 was detected only in Asiatic black bears (n = 4), SC02 was isolated from a Tibetian blue bear (n = 1), Asiatic black bears (n = 3), a sun bear (n = 1) and a northern raccoon (n = 1), and SC03 was identified in a sika deer (n = 1) (Tables 2 and 3).

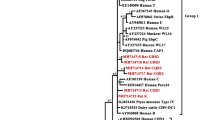

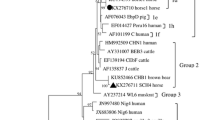

Phylogenetic analyses based on ITS sequencing indicated that all representative isolates detected in this work belong to Group 1 or Group 2 (Fig. 1). Specifically, isolates with the known genotypes (D and Peru 6) and the three new genotypes (SC01, SC02 and SC03) fell into Group 1, while strains with genotypes CHB1, BEB6 or CHS9 were categorized as Group 2. Moreover, the genotype D strains identified in this study clustered into Subgroup 1a, while the Peru 6, SC01 and SC02 strains and the SCO3 strains were clustered into subgroups 1b and 1 day, respectively (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic relationships of ITS nucleotide sequences of the Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and other reported genotypes. The phylogeny was inferred by a maximum likelihood analysis. Bootstrap values were obtained using 1,000 pseudoreplicates and greater than > 50 % was shown on nodes. The genotypes in this study are marked by empty triangles and the novel genotypes are marked by filled triangles

ITS analysis of the three novel genotypes showed genetic variability. There was a three-nucleotide difference between the ITS of SC01 strains and that of genotype CM3 (KF305589). The ITS sequences of SC02 strains isolated from Tibetian blue bears, Asiatic black bears, sun bears and northern raccoons differed from that of the CHN-DC1 genotype (KJ710333) by two SNPs. Finally, the ITS sequences harbored by strains of the newly-identified genotype SC03 contained four SNPs relative to that of genotype EbpC (KP262381).

MLST genotyping of E. bieneusi strains

In this study, 37, 33, 35 and 37 MS loci were successfully sequenced from the 43 ITS-positive specimens, respectively. For the MS1 locus, analysis of sequence polymorphisms, including trinucleotide TGC, TAA and TAC repeats, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) revealed eight distinct types (Types I–VIII). The TA indels and SNPs present in MS3 indicated three types (Type I– III), and analysis of a 35 bp minisatellite repeat region (TTA TTT TTT CCA TTT TTC TTC TTC TAT TTC CTT TA) and two regions of indels (GGTA and TTT TTT TCT T) in MS4 yielded 11 distinct types (Type I–XI). Finally, the MS7 marker exhibited a trinucleotide TAA repeat and several SNPs, generating 15 types (Type I–XV). Altogether, 31 specimens yielded positive amplification of each of these four loci, forming 27 distinct MLGs (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the occurrence of E. bieneusi infections among wildlife housed in zoos in southwest China. The overall infection rates in Chengdu Zoo and Bifengxia Zoo were 10.6 % and 29.7 %, respectively, indicating that E. bieneusi is a particularly common pathogen at Bifengxia Zoo. In contrast, Li et al. [26] previously detected E. bieneusi in 15.8 % of wildlife at Zhengzhou Zoo. Animals of the order Carnivora exhibited infection rates of 4.0 % and 27.0 % at Chengdu and Bifengxia Zoo, respectively. Prior studies have reported a similar range of E. bieneusi infection rates among animals of this order in China, including 11 % in pandas, 5.8 % in cats, 6.7 % in dogs, 12.3–27.7 % in foxes and 10.5 % in raccoon dogs [15, 16, 27, 28]. The low prevalence of E. bieneusi infections observed among animals of the order Primates in Chengdu Zoo (2 %) was nearly identical to that detected at Bifengxia Zoo (2.7 %). Notably, these infection rates were markedly lower than those detected at other zoos (15.2 %–44.8 %) by Karim et al. [29]. Similarly, previous studies detected infection rates of 11.5 % among a group of primates comprised of 23 nonhuman primate (NHP) species (158/1,386 animals) [30] and of 28.2 % and 12.3 % among free-ranging rhesus monkeys and newly captured baboons in Kenya, respectively [13, 31]. The prevalence of E. bieneusi among animals of the order Artiodactyla was 4 % in Chengdu Zoo, which was similar to that observed in golden takins (4.7 %) in a prior study [1], but markedly lower than the average infection rate detected in reindeers (16.8 %) and in dairy cattle (24.3 %) [32, 33]. Notably, no such animals tested at Bifengxia Zoo were infected with E. bieneusi. The results of this investigation indicate that the occurrence of E. bieneusi varies between zoos and animal species.

ITS sequencing and phylogenetic analyses detected two known (D and Peru 6) and three novel E. bieneusi genotypes (SC01, SC02 and SC03) among Group 1 strains, which exhibit zoonotic potential, whereas Group 2 was comprised of the CHB1, BEB6 and CHS9 genotypes. In Chengdu Zoo, seven genotypes were detected, with the zoonotic D genotype being the most prevalent followed by Peru 6. Notably, genotype D was found in four animal species, suggesting cross-transmission between these animals. Indeed, previous reports have detected genotype D in humans and wildlife in various different countries [34–37]. Therefore, these findings indicate that zoonotic transmission to humans and between wildlife species may occur in Chengdu Zoo. In Bifengxia Zoo, four E. bieneusi genotypes were identified, with CHB1 being the predominant genotype; this genotype was especially common among black bears. Our results provide the first evidence of CHB1 infection among Malayan sun bears, red pandas, brown bears, Tibetian blue bears and ring-tailed lemurs. Additionally, a recently published study reported CHB1 infection in black bears [26]. The common existence of the CHB1 genotype among animals of the family Ursidae indicates that these animals may be more susceptible to infection by E. bieneusi than other species housed at this zoo.

In this study, E. bieneusi infection was detected in a total of 18 wildlife species. Of these, six had previously never been found to be infected with this organism, including Asiatic golden cats, Tibetian blue bears, Malayan sun bears, brown bears, blackbucks and hog deer. As such, our findings extend the known host-range for this parasite. These newly identified hosts belong to the order Artiodactyla or Carnivora, indicating that animals in these orders may be more susceptible to infection by E. bieneusi. Two Malayan sun bears and an alpaca were observed to be infected with CHB1 and BEB6, respectively. In contrast, genotype J was identified in Malayan sun bears and genotypes CHALT1 and J were detected in alpacas in Zhengzhou Zoo [26]. Similar to the results of a previous study, we detected genotype BEB6 in sika deer [38]; we also detected the newly identified genotype SC03 in these animals. Interestingly, the isolation of two novel genotypes from these deer, as well as the five novel genotypes identified by the study of Zhao et al. [38] suggest that genetic variability between deer-derived E. bieneusi may be common. While previous studies reported infections with genotypes D, Ebpc, WL1, WL2, WL3 and WL15 in raccoons [26, 39], we detected only genotypes D and SC02 in these animals. However, the presence of the novel SC02 genotype indicates that raccoons likely harbor strains of E. bieneusi that have yet to be characterized. Tian et al. [27] detected the I-like and EbpC genotypes in giant pandas and red pandas, respectively. In contrast, we detected the Peru 6 genotype in giant pandas and the CHB1 genotype in red pandas. Recently, several studies have examined the prevalence and types of E. bieneusi infections among NHP species. These studies demonstrated that NHP can be infected by a wide range of genotypes, including Type IV, D, Henan V, Peru8, PigEBITS7, EbpC, WL15, LW1d, Peru11, Peru7, BEB6, I, O, EbpA, Henan-IV, BEB4, PigEBITS5, EbpD, CS-1, CM1–CM18, Macaque 1, Macaque 2 and KB1–KB6 [29–31, 40]. Here, we further these findings by providing the first evidence that NHP can be also infected by genotype CHB1, and by demonstrating that northern white-cheeked gibbons can harbor genotype D.

MLST analyses involving the amplification and sequencing of housekeeping genes are widely used to study genetic profiles of pathogens with high resolution, sensitivity and specificity. Indeed, this method plays an important role in parasite research, including in studies of Cryptosporidium and E. bieneusi, and has been applied to the evaluation of E. bieneusi strains isolated from humans, pandas, golden takins, baboons and other NHP [1, 22, 27, 40–46]. We therefore utilized this approach to analyze 43 ITS-positive E. bieneusi wildlife-derived isolates. Our analyses indicated that these 43 strains were comprised of 27 distinct MLGs. Several Asiatic black bears at Bifengxia Zoo were infected with the same three MLGs (MLG14, MLG19 and MLG23), indicating likely transmission of E. bieneusi between these animals. Interestingly, despite belonging to distinct orders, both a ring-tailed lemur (Primates) and an Asiatic black bear (Carnivora) were infected with MLG16; however, it is unclear which animal was the source of the infection. To our surprise, the same MLG was never detected within two animals of the same species at Chengdu Zoo. Indeed, 12 distinct MLGs were detected among Asiatic black bears. Likewise, other species were infected with multiple different MLGs. These findings indicate that there is a significant level of genetic variability among E. bieneusi strains.

Conclusions

The results of our study describe the prevalence of E. bieneusi infections among captive wildlife in zoos in southwest China. Furthermore, they provide the first evidence of E. bieneusi infections in Asian golden cats, Tibetian blue bears, blackbucks, hog deer, Malayan sun bears and brown bears, thereby expanding the recognized host-range of this organism. The detection of zoonotic genotypes among various animals highlights the potential for zoonotic transmission to humans. Thus, methods for controlling this transmission are needed. Our novel E. bieneusi sequencing data will facilitate future molecular epidemiology research. However, further multi-locus genotyping analyses, involving a larger number of isolates from humans and wildlife, are needed to better assess the zoonotic potential and transmission dynamics of E. bieneusi.

Abbreviations

ITS, internal transcribed spacer; MLST, Multilocus sequence typing; MLGs, Multilocus genotyping; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

Zhao GH, Du SZ, Wang HB, Hu XF, Deng MJ, Yu SK, et al. First report of zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in golden takins (Budorcas taxicolor bedfordi). Infect Genet Evol. 2015;34:394–401.

Didier ES. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 2005;94(1):61–76.

Wagnerová P, Sak B, McEvoy J, Rost M, Sherwood D, Holcomb K, et al. Cryptosporidium parvum and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in American mustangs and Chincoteague ponies. Exp Parasitol. 2016;162:24–7.

Hu Y, Feng Y, Huang C, Xiao L. Occurrence, source, and human infection potential of Cryptosporidium and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in drinking source water in Shanghai, China, during a pig carcass disposal incident. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(24):14219–27.

Dengjel B, Zahler M, Hermanns W, Heinritzi K, Spillmann T, Thomschke A, et al. Zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(12):4495–9.

Fiuza V, Oliveira F, Fayer R, Santín M. First report of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pigs in Brazil. Parasitol Int. 2015;64(4):18–23.

Didier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: current status. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19(5):485.

Gill EE, Fast NM. Assessing the microsporidia-fungi relationship: combined phylogenetic analysis of eight genes. Gene. 2006;375:103–9.

Anane S, Attouchi H. Microsporidiosis: epidemiology, clinical data and therapy. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34(8):450–64.

Didier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: not just in AIDS patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(5):490.

Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124(1):80–9.

Van Gool T, Luderhoff E, Nathoo K, Kiire C, Dankert J, Mason P. High prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections among HIV-positive individuals with persistent diarrhoea in Harare, Zimbabwe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89(5):478–80.

Maikai BV, Umoh JU, Lawal IA, Kudi AC, Ejembi CL, Xiao L. Molecular characterizations of Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Enterocytozoon in humans in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Exp Parasitol. 2012;131(4):452–56.

Santin M, Fayer R. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype nomenclature based on the internal transcribed spacer sequence: a consensus. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2009;56(1):34–8.

Li W, Li Y, Song M, Lu Y, Yang J, Tao W, et al. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Giardia duodenalis in cats and dogs in Heilongjiang province. China Vet Parasitol. 2015;208(3–4):125–34.

Yang Y, Lin Y, Li Q, Zhang S, Tao W, Wan Q, et al. Widespread presence of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype D in farmed foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in China: first identification and zoonotic concern. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(11):4341–8.

Thellier M, Breton J. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human and animals, focus on laboratory identification and molecular epidemiology. Parasite. 2008;15(3):349–58.

Kapel CM, Fredensborg BL. Foodborne parasites from wildlife: how wild are they? Trends Parasitol. 2015;31(4):125–7.

Liu X, Xie N, Li W, Zhou Z, Zhong Z, Shen L, et al. Emergence of Cryptosporidium hominis Monkey Genotype II and Novel Subtype Family Ik in the Squirrel Monkey (Saimiri sciureus) in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141450.

Liu X, Zhou X, Zhong Z, Deng J, Chen W, Cao S, et al. Multilocus genotype and subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium andersoni derived from a Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) in China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(6):2129–36.

Shi K, Li M, Wang X, Li J, Karim MR, Wang R, et al. Molecular survey of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sheep and goats in China. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):1369–79.

Feng Y, Li N, Dearen T, Lobo ML, Matos O, Cama V, et al. Development of a multilocus sequence typing tool for high-resolution genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(14):4822–8.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi. Accessed 5 Mar 2016.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–82.

Molecular evolutionary Genetics Analysis. http://www.megasoftware.net/. Accessed 5 Mar 2016.

Li J, Meng Q, Chang Y, Wang R, Li T, Dong H, et al. Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Captive Wildlife at Zhengzhou Zoo, China. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015;62(6):833–9.

Tian GR, Zhao GH, Du SZ, Hu XF, Wang HB, Zhang LX, et al. First report of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and red pandas (Ailurus fulgens) in China. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;34:32–5.

Zhang XX, Cong W, Lou ZL, Ma JG, Zheng WB, Yao QX, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and multilocus genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in farmed foxes (Vulpes lagopus), Northern China. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):1–7.

Karim MR, Dong H, Li T, Yu F, Li D, Zhang L, et al. Predomination and new genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive nonhuman primates in zoos in China: high genetic diversity and zoonotic significance. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117991.

Karim MR, Wang R, Dong H, Zhang L, Li J, Zhang S, et al. Genetic polymorphism and zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from nonhuman primates in China. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(6):1893–8.

Jianbin Y, Lihua X, Jingbo M, Meijin G, Lili L, Yaoyu F. Anthroponotic enteric parasites in monkeys in public park. China Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(10):1640–3.

Liu W, Nie C, Zhang L, Wang R, Liu A, Zhao W, et al. First detection and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in reindeers (Rangifer tarandus): a zoonotic potential of ITS genotypes. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8(1):1–5.

Li J, Luo N, Wang C, Qi M, Cao J, Cui Z, et al. Occurrence, molecular characterization and predominant genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in dairy cattle in Henan and Ningxia. China Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):1–5.

Breton J, Bart-Delabesse E, Biligui S, Carbone A, Seiller X, Okome-Nkoumou M, et al. New highly divergent rRNA sequence among biodiverse genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi strains isolated from humans in Gabon and Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2580–9.

Maikai BV, Umoh JU, Lawal IA, Kudi AC, Ejembi CL, Xiao L. Molecular characterizations of Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Enterocytozoon in humans in Kaduna State. Nigeria Exp Parasitol. 2012;131(4):452–6.

Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(2):557–63.

Santín M, Fayer R. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res Vet Sci. 2011;90(3):363–71.

Zhao W, Zhang W, Wang R, Liu W, Liu A, Yang D, et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sika deer (Cervus nippon) and red deer (Cervus elaphus): deer specificity and zoonotic potential of ITS genotypes. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(11):4243–50.

Sulaiman IM, Ronald F, Lal AA, Trout JM, Schaefer FW, Lihua X. Molecular characterization of microsporidia indicates that wild mammals Harbor host-adapted Enterocytozoon spp. as well as human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(8):4495–501.

Li W, Kiulia NM, Mwenda JM, Nyachieo A, Taylor MB, Zhang X, et al. Cyclospora papionis, Cryptosporidium hominis, and human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive baboons in Kenya. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(12):4326–9.

Li N, Xiao L, Cama VA, Ortega Y, Gilman RH, Guo M, Feng Y. Genetic recombination and Cryptosporidium hominis virulent subtype IbA10G2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(10):1573–82.

Zhao GH, Ren WX, Gao M, Bian QQ, Hu B, Cong MM, et al. Genotyping Cryptosporidium andersoni in cattle in Shaanxi province. Northwestern China PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60112.

Wang R, Jian F, Zhang L, Ning C, Liu A, Zhao J, Feng Y, et al. Multilocus sequence subtyping and genetic structure of Cryptosporidium muris and Cryptosporidium andersoni. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43782.

Li W, Cama V, Akinbo FO, Ganguly S, Kiulia NM, Zhang X, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Enterocytozoon bieneusi: lack of geographic segregation and existence of genetically isolated sub-populations. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:111–9.

Karim MR, Wang R, He X, Zhang L, Li J, Rume FI, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in nonhuman primates in China. Vet Parasitol. 2014;200(1):13–23.

Li W, Cama V, Feng Y, Gilman RH, Bern C, Zhang X, et al. Population genetic analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in humans. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42(3):287–93.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Huaiyi Su for collecting samples and Xiaoyang Xu for comments on the draft manuscript.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (CPF2014-14; CPF2015-4).

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. Representative sequences are submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers: KU852462–KU852485, KX423961, KU871860–KU871896, KU871897–KU871930, KU871931–KU871965, and KU871966–KU872002.

Authors’ contributions

Experiments were conceived and designed by GP and WL. XY, QW, LN, JD and LW collected samples. Experiments were performed by WL, DL, ZZ, XL, NX and SL, and the data were analyzed by YH, HF, HX and YG. The manuscript was written by WL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Wildlife Management and Animal Welfare Committee of China. No animals were harmed during the sampling process. Permission was obtained from Zoo owners prior to collection of fecal specimens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of mammals in Chengdu Zoo examined in the present study. Common name, scientific name, number of specimens tested and number of samples positive for Enterocytozoon bieneusi, genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi are provided. (XLSX 12 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

List of mammals in Bifengxia Zoo examined in the present study. Common name, scientific name, number of specimens tested and number of samples positive for Enterocytozoon bieneusi, genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi are provided. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Deng, L., Yu, X. et al. Multilocus genotypes and broad host-range of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive wildlife at zoological gardens in China. Parasites Vectors 9, 395 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1668-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1668-1