Abstract

Background

The Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, located in Maranhão, Brazil, is a region of exceptional beauty and a popular tourist destination. The adjoining area has suffered from the impact of human activity and, consequently, has experienced outbreaks of leishmaniasis. This study aimed to evaluate the composition, abundance, species richness and seasonal distribution of sand flies in the region and to determine the constancy of the insect population.

Methods

The survey was conducted at three sites located in the municipalities of Barreirinhas and Santo Amaro between September 2012 and August 2013. Sampling was performed monthly using automatic light traps installed 1.5 m above the soil adjacent to 13 randomly selected rural dwellings. At each site, one trap was placed in the peridomicile near to animal enclosures and another (extradomicile) at 500 m from the peridomicile.

Results

A total of 4,474 individual sand flies were collected over the year with the highest abundance recorded during the rainy season (December to June). Nine species were collected: L. whitmani, L. longipalpis, L. lenti, L. sordellii, L. evandroi, L. flaviscutellata, L. wellcomei, L. termitophila and L. intermedia. Although peridomiciliary and extradomiciliary environments presented similar species richness, the Shannon diversity index was significantly lower in the former (H’ = 2.4) compared with the latter (H’ = 4.98). Lutzomyia whitmani and L. longipalpis were the most abundant species and were classified as constant (constancy index, CI = 100 %) along with L. lenti (CI = 58.3), L. evandroi (CI = 58.3) and L. sordellii (CI = 66.7). The remaining four species presented CI values between 25 and 50 % and were considered accessory.

Conclusions

The present results confirm the present of L. whitmani and L. longipalpis in the peridomicile of houses in Lençóis National Park. The abundance of these species could explain, respectively, the endemicity of cutaneous leishmaniasis and sporadic cases of visceral leishmaniasis in the study area. However, in the case of cutaneous leishmaniasis, the presence of other sand fly vectors (in addition to L. whitmani) cannot be neglected. Finally, this study emphasizes the need for a more effective and permanent supervision to control the expansion of these vectors and leishmaniasis outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Leishmaniasis comprises a group of parasitic diseases caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae). The most common forms of the disease are tegumentary leishmaniasis (TL), with around one million cases recorded globally in the last five years, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL), of which it is estimated that 200,000 to 400,000 new cases occur worldwide each year. However, more than 90 % of notified cases occur in half of the six countries including Brazil, some regions of which exhibit high endemicity for the disease [1].

The principal mechanism of transmission of Leishmania spp. to mammals, including humans, is through the bite of Leishmania-infected female sand fly (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) of the genera Lutzomyia in the New World and Phlebotomus in Old World [2]. In Brazil, epidemiological surveys carried out in rural and peri-urban areas of the northern state of Maranhão (MA) with recorded cases of TL and VL revealed the presence of at least 91 species of sand flies, of which 87 belonged to the genus Lutzomyia and 4 were of the genus Brumptomyia [3]. Species diversity was very high within primary forest environments but decreased somewhat in altered primary and secondary forests [4, 5]. Moreover, sand flies were found infesting the man-made environment, particularly dwellings associated with domestic animals, where the possibility of feeding on human blood was considerably enhanced [6].

One of the main regions of Leishmania transmission in Maranhão encompasses the important conservation zone designated Lençóis Maranhenses National Park (2°19 '- 2°45' S; 42°44 '- 43°29' W). This protected area, which comprises 155,000 ha with a perimeter of 270 km, is characterized by large dunes of white sand interspersed with lagoons and represents, a key tourist destination in the state. While the park itself extends through the municipalities of Barreirinhas, Santo Amaro and Primeira Cruz, the main point of entry is via Barreirinhas [7]. This municipality and its adjacent areas have, therefore, received various tourism-related investments over the years with the emergence of numerous developments and the expansion of municipal headquarters. The accompanying growth in the number of inhabitants, which has risen from 29,640 in 1991 to 43,000 in 2010 [8], and the increase in tourist activity have exerted significant cultural, economical and environmental impacts on the area with consequential public health problems, including outbreaks of leishmaniasis [9]. During the period 2000 to 2008 some 737 cases of TL were notified in the town of Barreirinhas alone, with high coefficients of detection per 100,000 inhabitants in 2000 (308.2), 2001 (310.9), 2002 (338.2) and 2005 (313.6). Furthermore, between 2009 and 2014 the number of cases remained high with 453 notified occurrences [10], placing this town in a prominent position in the state scenario of leishmaniasis [9].

Preliminary studies carried out in Barreirinhas and the surrounding villages revealed that the main sand flies present were the recognized Leishmania vectors, Lutzomyia whitmani, L. longipalpis and L. flaviscutellata [11]. However, no studies concerning the structure of the insect communities in the area or the epidemiology of the disease have been performed so far. The aims of the present investigation were to evaluate the composition, abundance, species richness and seasonal distribution of sand flies in the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, and to determine the constancy index of the insect populations.

Methods

The collection of sand flies was authorized by Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) register: Sisbio/ICMbio 46319–1. The objectives of the project were explained to the owners of the farms where the light traps would be exposed, and they were then invited to take part in the project and sign an informed consent.

Study area

Surveys were carried out in two municipalities of Maranhão State. Barreirinhas (2°45'S; 42°5'W), located 266 km from the state capital São Luis, encompasses an area of 3,111 km2 and 67 % of its 43,000 inhabitants reside in rural districts [8]. Santo Amaro (2°30′S; 43°15′W), located 243 km from the state capital, encompasses an area of 1,601 km2 and 73 % of its 13,820 inhabitants reside in rural districts [8]. The study area has a semi-humid tropical climate with a mean annual rainfall of 1,900 mm, the major portion of which (96 %) occurs during the rainy season from December to June while the remaining 4 % falls sporadically in the dry season from July to November.

Insect sampling

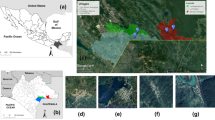

From September 2012 to August 2013, 26 automatic HP light traps [12] were installed at 1.5 m above the soil in the surroundings of 13 randomly selected rural dwellings named Manoelzinho (n = 5), Palmeira dos Eduardos (n = 3), both located in Barreirinhas municipality, and Riachão (n = 5), located in Santo Amaro municipality. Each dwelling received two traps, one placed within the peridomicile near to animal enclosures (chicken pens, pigsties or cowsheds) wherever possible, and the other located 500 m from the peridomicile in the extradomiciliary environment [the sandy coastal environment (forest)] (Fig. 1). Each trap was operated for 12 h uninterruptedly, one night per month, (from 18:00 to 06:00 h) on new moon nights, such that the effort to capture sand flies totaled 3, 744 h (i.e. 26 traps × 12 h × 12 months). The captured insects were placed in 1.5 ml plastic tubes, killed by freezing at −20 °C and transported to the Laboratory of Entomology and Vectors of the Pathology Department at the Universidade Federal do Maranhão. Sand flies were separated from the other insects and treated with a solution containing potassium hydroxide, acetic acid and lactophenol in distilled water. After clarification, specimens were placed in Berlese’s fluid and mounted individually between slides and cover slips. Sand flies were examined under the optical microscope and identified at the species level according to the dichotomous key provided by Young and Duncan [13].

Localization of the Brazilian State of Maranhão and the municipalities in which the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park is situated a. Spatial arrangement of the sampling sites located at Riachão in the municipality of Santo Amaro b, and at Manoelzinho (c) and Palmeira dos Eduardos (d) located in the municipality of Barreirinhas

Data analysis

Data were organized in spreadsheets using Microsoft Excel 2007 and descriptive statistical analyses was performed with the aid of Statistica software version 7.0 (StatSoft South America, São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo, Brazil). The diversity of species was calculated according to the Shannon diversity index (H’) using PAST software version 2.04 [14]. The constancy index (CI) was employed to classify species as constant (CI > 50 %), accessory (25 % ≤ CI ≥ 50 %) or accidental (CI < 25 %) [15]. Data relating to rainfall, temperature and humidity were provided by the Núcleo Geo-Ambiental of the Universidade Estadual do Maranhão, and correlations between sand fly abundance and climatic parameters were tested by means of Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (rs).

Results

Species richness and diversity

Nine species of Lutzomyia were identified among the 4,474 sand fly specimens collected (Table 1). Although both peridomiciliary and extradomiciliary environments presented similar values for species richness, the Shannon diversity index was considerably lower in the former settings (H’ = 2.4) than in the latter (H’ = 4.98).

Abundance of sand flies

The most abundant sand fly species were L. whitmani (46.85), L. longipalpis (43.25), L. lenti (3.67), L. sordellii (2.35) and L. flaviscutellata (1.63 %), while the remaining four species together accounted for only 2.26 % (Table 1). In general, male sand flies predominated over females (54 and 46 %, respectively), although this distribution was influenced mainly by the abundance of L. whitmani and L. longipalpis males, which contributed 51.03 and 40.55 %, respectively, of all specimens collected.

In the peridomiciliary settings, the most abundant species were L. whitmani (50.49) and L. longipalpis (45.90 %), while the remaining seven species accounted for only 3.61 % of the total number of specimens captured. In the extradomiciliary environments, the most abundant species were L. whitmani (34.39 %), L. longipalpis (34.19 %), L. lenti (10.67 %), L. sordellii (8.40 %) and L. flaviscutellata (6.32 %), with the remaining four species accounting for 6.03 % of the total number of specimens trapped (Table 1).

The relative abundance of species was significantly greater in peridomiciliary environments than in extradomiciliary settings (F = 4.95; degrees of freedom = 1; P < 0.01), and the total number of sand flies captured in peridomicile traps was significantly higher in comparison with extradomicile traps (χ2 = 723. 28; degrees of freedom = 1; P < 0.01).

Constancy index and seasonal distribution of sand flies

Although sand flies were found in the study areas all year around, only five species could be considered constant, L. whitmani, L. longipalpis (CI = 100 %), L. sordellii (CI = 66.7 %), L. lenti and L. evandroi (CI = 58.3 %) (Table 2). The other four species were considered accessory since they presented CI values between 25 and 50 %.

All species were present during at least one month of both dry and rainy seasons, although the distribution was somewhat irregular. Species richness was highest in January at the start of the rainy season, and representatives of all nine species were captured in the traps during this period. Subsequently, however, the frequency of some species declined such that specimens representing just two species were trapped during April and May. Species representation was more uniformly distributed during the months of the dry season, with a minimum of five species being captured throughout the period with the exception of October when only four species were captured.

Regarding the pattern of species abundance, considerable numbers of sand flies were captured throughout the year, but most especially in the rainy season when the total number of specimens obtained (60.7 % of the total) was significantly higher in comparison with the dry season (χ2 = 103.04; degrees of freedom = 1; P < 0.01). The highest abundance of sand flies (680 specimens captured) was observed in the mid-rainy season month of April, whilst the lowest abundance (166 specimens captured) was recorded in the mid-dry season month of September. In any month, the abundance of sand flies was determined by the two predominant species L. whitmani and L. longipalpis (Fig. 2). Moreover, the abundance of sand flies exhibited a positive correlation with rainfall (rs = 0.755; P = 0.003) and humidity (rs = 0.597; P = 0.021) but a negative correlation with temperature (rs = − 0.523; P = 0.042).

Discussion

Although the region comprising the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park is located on the eastern border of the tropical Amazon rainforest, its climate is semi-humid tropical. The species richness of the sand flies fauna in this area was comparable with that established for other locations in the semi-humid tropical zone typical of northeastern Brazil [16, 17], but lower than that of locations in the Amazon humid zone [5, 18, 19].

The infestation of sand flies in anthropic settings around Barreirinhas and Santo Amaro was most likely caused by deforestation and disturbance of green areas associated with urban expansion, a situation that has been observed previously in towns of southern Brazil [20]. Ramos et al. [21] showed that both forest cover and human population density affect sand fly diversity and abundance. These effects may be amplified when both factors are conjoined. Low forest cover can reduce sand fly numbers, but high human population density can produce environmental conditions favorable for maintaining the life cycles of several sand fly species that are adaptable to these environments [21].

Although similar sand fly species were captured in the peridomicile and extradomicile traps surveyed, the abundance of sand flies was significantly higher in the peridomiciliary settings. Martin and Rebêlo [17] reported a similar pattern of sand fly abundance in the municipality of Santa Quitéria, which is close to Barreirinhas, and suggested that the discrepancy between the settings might reflect a structural difference in the sand fly communities. If this were true, then the sand fly communities in the two settings would be characterized by species with dissimilar degrees of adaptation and diverse responses to the availability of blood sources, breeding nests and shelter conditions. According to Azevedo et al. [22], however, due consideration must also be given to the power of attraction of the light trap, the range of action of which is around 5 m for small insects such as sand flies [23, 24]. On this basis, it is possible that the most abundant species were sheltered close to the traps and, therefore, readily attracted, while the less common species could be accidental or occasional visitors.

Nevertheless, L. whitmani was the predominant species and, possibly, the best adapted to the anthropic environment since it was found in high abundance in both peridomiciliary and extradomiciliary settings of the present study and in surveys of other TL-transmission zones in Maranhão [25, 26] and in northern and south-eastern Brazil [27]. Lutzomyia longipalpis also favored the feeding and breeding grounds in the peridomiciliary settings of poor rural areas, thus perpetuating the VL transmission cycle among domestic animals and humans [28]. The high prevalence of these two species was expected since their presence in the area had been reported previously [3, 9], and their frequency throughout the year in modified environments has been observed in other geographical areas, as in Minas Gerais [29].

Among the other constant species identified in the present study, L. lenti is of particular interest because of the potential threat to human health since L. braziliensis-infected specimens of this species have been detected in Minas Gerais [30]. Lutzomyia lenti is well distributed in Brazil and is to be found in marginal areas, in the lairs of wild animals, in the shelters of domestic animals (chicken pens, pigsties and cowsheds) and in the external and internal walls of human dwellings [31]. Similarly, L. sordellii is reportedly present in all Brazilian regions [32], having been detected in tree trunks, rock crevices and caves, as well as inside domestic animal shelters and human domiciles [16, 33].

Lutzomyia evandroi is an anthropophilic sand fly that is widely distributed in Brazil and associated mainly with peridomiciliary settings [11]. The distribution of L. evandroi is similar to that of L. longipalpis, as demonstrated by research carried out in the eastern parts of Maranhão [17, 26] and in other locations [34, 35]. However, L. evandroi appears to be more opportunistic than L. longipalpis in relation to habitat, although [36] reported that the density of L. evandroi was higher in chicken pens than in pigsties or cowsheds. While the vectorial ability of L. evandroi in the transmission of human TL has not yet been demonstrated some studies indicate that this species may be implicated in the transmission of Leishmania infantum to dogs [37]. Furthermore, the gregarine Ascocystis chagasi and a non-identified trypanosomatid have been found in the gut of Lutzomyia evandroi during an outbreak of leishmaniasis in São Luis, the capital of Maranhão [38].

In the present study, L. flaviscutellata exhibited an irregular season distribution and, for this reason, it was classified as an accessory species, as mentioned previously by Barros et al. [39]. Although L. flaviscutellata was originally considered a strictly wild species, it is becoming adapted to shrubbery vegetation (secondary forests) [39], and peridomiciliary [40] and domiciliary settings. The vectorial potential of L. flaviscutellata in the transmission of TL has been demonstrated [41] and its presence in the environs of the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park has important epidemiological significance in the transmission of Leishmania amazonensis [41, 42], one of the major etiological agents of diffuse TL in Maranhão [43].

Along with L. whitmani and L. intermedia, L. wellcomei has been recognized as a vector of L. braziliensis in wild settings of northeastern Brazil [44]. Since L. wellcomei occurs almost exusively during the rainy season and maintains the typical behavior of a wild species [45], it was classified as an accessory species in the present study.

The seasonal distributions of L. termitophila and L. intermedia presented similar profiles in the present study, and both were classified as accessory species. The presence of L. termitophila has been reported in various Brazilian states [46] and was described as an inhabitant of termite colony [47].

With respect to L. intermedia, its presence at the sampling sites is of particular note since the species has not been previously detected in this area despite intensive and protracted investigations [9, 11]. However, L. intermedia has a widespread distribution, occurring in the Northeast, Southeast and Center-West regions of Brazil [48], and from the Atlantic coast to northern Argentina and southern Bolivia, as well as in diversified climates and altitudes [49]. Furthermore, L. intermedia have been reported to present a synanthropic habit [50], such also affirmed by Rangel et al. [51] , who described the highly anthropophilic behaviour of leishmaniasis in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The sudden emergence of L. intermedia in the environs of the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park is a cause for concern and requires further detailed investigation since the species is considered a good vector for L. braziliensis [32]. Additionally, specimens of L. intermedia naturally infected with L. braziliensis have been found in TL endemic areas in southeastern and southern Brazil [32, 48, 52].

The abundance of sand fly specimens was significantly higher during the rainy season than in the dry season, a finding that is in accord with previous reports [53], but in conflict with some studies performed in other areas of Maranhão [17, 18]. In the present study, rainfall and humidity were positively correlated with the abundance of sand flies, whereas temperature was negatively correlated. Statistically significant correlations between climatic parameters and sand fly abundance were reported by Almeida et al. [54] following a study conducted in Ponta Porã, Mato Grosso do Sul, although such correlations could not be established in surveys carried out in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais [55] or in São Luís, MA [4]. The sites surveyed in the present study were located in an equatorial region such that the air temperature only varied between 25.0 and 28.1 °C during the year. In this case, the negative correlation between temperature and sand fly abundance could be explained by the influence of rainfall, since the largest numbers of insects were captured during periods with the highest precipitation indices, which corresponded with those presenting the lowest temperatures. However, the finding of increased numbers of sand flies following months of heavy rainfall reinforces the hypothesis that increased humidity resulting from intense precipitation promotes the emergence of winged forms of sand flies [55].

Conclusions

This study confirms the presence of L. whitmani and L. longipalpis in the peridomicile of houses present in Lençóis National Park. The predominance of L. whitmani as well as other potential vectors of L. braziliensis could explain the endemicity of TL in the study area. In the same way, the high abundance of L. longipalpis could explain the sporadic cases of VL. The study highlights the need for a more effective and permanent surveillance regime in order to control the expansion of vectors of leishmaniasis and to minimize outbreaks of the disease. It is important to stress that it is the health and well-being not only of the inhabitants of the region that is at risk but also of the thousands of tourists that visit the conservation and recreational area of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park. Nature-based tourism provides valuable revenue to sustain local communities and to support conservation, education, and wildlife research; hence it is of utmost importance to prioritize health and safety in this area.

Abbreviations

- TL:

-

Tegumentary leishmaniasis

- VL:

-

Visceral leishmaniasis

References

WHO – World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/en/ (2014). Accessed 22 Dec 2014.

Ready PD. Biology of phlebotomine sand flies as vectors of disease agents. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:227–50.

Rebêlo JMM, Rocha RV, Moraes JLP, Silva CRM, Leonardo FS, Alves GA. The fauna of phlebotomines (Diptera, Psychodidae) in different phytogeographic regions of the state of Maranhão, Brazil. Rev Bras Entomol. 2010;54:494–500.

Marinho RM, Fonteles RS, Vasconcelos GC, Azevêdo PCB, Moraes JLP, Rebêlo JMM. Phlebotomines (Diptera, Psychodidae) in forest reserves in the metropolitan area of São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. Rev Bras Ent. 2008;52:112–6.

Campos AM, Matavelli R, CLC S d, Moraes LS, Rebêlo. Ecology of Phlebotomines (Diptera: Psychodidae) in a transitional area between the Amazon and the Cerrado in the State of Maranhão, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:52–8.

Oliveira-Pereira YN, Rebêlo JMM, Moraes JLP, Pereira SRF. Molecular diagnosis of the natural infection rate due to Leishmania sp in sandflies (Psychodidae, Lutzomyia) in the Amazon region of Maranhão, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:540–43.

D’Antona AO. O lugar do Parque Nacional no espaço das comunidades dos lençóis Maranhenses. Brasília: Ed. IBAMA; 2000.

IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2013). http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun=211027&search=maranhao|santo-amaro-do-maranhao. Accessed 03 Dec 2014.

Assunção Júnior AN, Silva O, Moraes JLP, Nascimento FRF, Oliveira-Pereira YN, Costa JML, et al. Emerging focus of tegumentary leishmaniasis around “Parque Nacional Dos Lençóis Maranhenses”, Northeast Brazil. Gazeta Medica da Bahia. 2009;79:103–9.

SINAN – Sistema de Informação de Informação de Agravos de Notificação (2014). Secretaria Municipal de Saúde de Barreirinhas.

Rebêlo JMM, Assunção-Júnior AN, Silva O, Moraes JLP. Occurrence of sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) in leishmaniasis foci in an ecotourism area around the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2010;26:195–98.

Pugedo H, Barata RA, França-Silva JC, Silva JC, Dias ES. HP: an improved model of sucction light trap for the capture of small insects. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:70–2.

Young DC, Duncan MA. Guide to the identification and geographic distribution of Lutzomyia sand flies in Mexico, the West Indies, Central and South America (Diptera: Psychodidae). Mem Amer Entomol Inst. 1994;54:1–881.

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron. 2001;4:1–9.

Silveira Neto S, Nakano O, Barbin D, Villa Nova NA. Manual de ecologia dos insetos. Ed. Agronômica Ceres: Piracicaba; 1976.

Carvalho MR, Valença HF, Silva FJ, Pita-Pereira D, de Araújo Pereira T, Britto C, et al. Natural Leishmania infantum infection in Migonemyia migonei (França, 1920) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) the putative vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010;116:108–10.

Martin AMCB, Rebêlo JMM. Spatial-temporal dynamics of phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera, Psychodidae) in the municipality of Santa Quitéria, "cerrado'' area, State of Maranhão, Brazil. Iheringia Ser Zool. 2006;96:283–88.

Silva DF, Freitas RA, Franco AMR. Diversity and abundance of phlebotomine of the genus Lutzomyia (Diptera: Psychodidae) in areas of forest in the northeast of Manacapuru, Amazonas State, Brazil. Neotrop Entomol. 2007;36:138–44.

Azevedo ACR, Costa SM, Pinto MCG, Souza JL, Cruz HC, Vidal J, et al. Studies on the sandy fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) from transmission areas of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in state of Acre, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:760–67.

Cerino DA, Teodoro U, Silveira TGV. Sand Flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the urban area of the municipality of Cianorte, Paraná State, Brazil. Neotrop Entomol. 2009;38:853–58.

Ramos WR, Medeiros JF, Julião GR, Ríos-Velásquez CM, Marialva EF, Desmouliére SJM, et al. Anthropic effects on sand fly (Diptera: Psychodidae) abundance and diversity in an Amazonian rural settlement, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2014;139:44–52.

Azevedo PC, Lopes GN, Fonteles RS, Vasconcelos GC, Moraes JL, Rebêlo JM. The effect of fragmentation on phlebotomine communities (Diptera: Psychodidae) in areas of ombrophilous forest in São Luís, state of Maranhão, Brazil. Neotrop Entomol. 2011;40:271–7.

Dye C, Davies CR, Lainson R. Communication among phlebotomine sandflies: a field study of domesticated Lutzomyia longipalpis populations in Amazonian Brazil. Anim Behav. 1991;42:183–92.

Killick-Kendrick R, Wilkes TJ, Alexander J, Bray RS, Rioux JA, Bailly M. The distance of attraction of CDC light traps to phlebotomine sandflies. Annales de Parasitologie et Humaine Comparée. 1985;60:763–67.

Leonardo FS, Rebêlo JMM. Lutzomyia whitmani periurbanization in a focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the State of Maranhão, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37:282–4.

Silva FS, Carvalho LP, Cardozo FP, Moraes JL, Rebêlo JM. Sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in a Cerrado area of the Maranhão state, Brazil. Neotrop Entomol. 2010;39:1032–38.

Andrade-Filho JD, Valente MB, Andrade WA, Brazil RP, Falcão AL. Phlebotomine sand flies in the State of Tocantins, Brazil (Diptera: Psychodidae). Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2001;34:323–29.

Missawa NA, Lorosa ES, Dias ES. Feeding preference of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) in transmission area of visceral leishmaniasis in Mato Grosso. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:365–8.

Saraiva L, Andrade Filho JD, Falcão AL, Carvalho DAA, Souza CM, Freitas CR, et al. Phlebotominae fauna (Diptera: Psychodidade) in an urban district of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, endemic for visceral leishmaniasis: Characterization of favores locations as determined by spatial analysis. Acta Trop. 2011;117:137–45.

Margonari C, Soares RP, Andrade-Filho JD, Xavier DC, Saraiva L, Fonseca AL, et al. Phlebotominae Sand Flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) and Leishmania Infection in Gafanhoto Park, Divinópolis, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:1212–9.

Aguiar GM, Medeiros WM. Distribuição regional e habitats das espécies de flebotomíneos do Brasil. In: Rangel EF, Lainson R, editors. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003.

Rangel EF, Lainson R. Ecologia das Leishmanioses: Transmissores de Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana. In: Rangel EF, Lainson R, editors. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003. p. 291–309.

Brandão Filho SP, Donalisio MR, da Silva FJ, Valença HF, Costa PL, Shaw JJ, et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of occurrence of Lutzomyia sand fly species in an endemic area for cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Atlantic Forest region of northeast Brazil. J Vector Ecol. 2011;36:71–6.

Brazil RP, Passos WL, Fuzari AA, Falcão AL, Andrade Filho JD. The peridomiciliar sand fly fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae) in areas of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Além Paraíba, Minas Gerais. Brazil J Vector Ecol. 2006;2006(31):418–20.

Felipe IMA, de Aquino DMC, Kuppinger O, Santos MDC, Rangel MES, Barbosa DS, et al. Leishmania infection in humans, dogs and sandflies in a visceral leishmaniasis endemic area in Maranhão, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:207–11.

Silva FS, Carvalho LPC, Souza JM. Flebotomíneos (Diptera: Psychodidae) associados a abrigos de animais domésticos em área rural do Nordeste do Estado do Maranhão, Brasil. Revista de Patologia Tropical. 2012;41:337–47.

Sherlock I. Ecological interactions of visceral leishmaniasis in the state of Bahia, Brazil. Mem Institut Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91:671–83.

Brazil RP, Ryan L. Nota sobre a infecção de Lutzomyia evandroi (Diptera: Psychodidae) por Ascocystis chagasi (Adler & Mayrink, 1961) no Estado do Maranhão. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1984;79:375–76.

Barros VLL, Rebêlo JMM, Silva FS. Sandflies (Diptera, Psychodidae) in a secondary forest area in the county of Paço do Lumiar, Maranhão. Brazil: a leishmaniasis transmission area. Entomologia y Vectores. 2000;2000(16):265–70.

Reis SR, Gomes LHM, Ferreira NM, Nery LCR, Pinheiro FG, Figueira LP, et al. Occurrence of sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the peridomestic environment in an area of transmission focus for cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Manaus, Amazon. Acta Amazon. 2013;43:123–5.

Lainson R, Shaw JJ, Leishmaniasis in Brazil. I. Observations on enzootic rodent leishmaniasis – Incrimination of Lutzomyia flaviscutellata (Mangabeira) as the vector in the lower Amazonian basin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62:385–95.

Shaw JJ, Lainson R. Leishmaniasis in Brazil: II Observations on enzootic rodent leishmaniasis in the lower amazon region – The feeding habitats of the vector, Lutzomyia flaviscutellata in reference to man, rodents and other animals. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;1968(62):396–405.

Costa JML, Saldanha ACR, Mello E, Silva AC, Serra-Neto A, Galvão CES, et al. Estado atual da leishmaniose cutânea difusa (LCD) no Maranhão. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1992;25:115–23.

Silva DF, Vasconcelos SD. Phlebotomine sandflies in fragments of rain forest in Recife, Pernambuco State. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:264–6.

Pinheiro MPG, Silva JHT, Silva VEP, Andrade MJM, Ximenes MFFM. Lutzomyia wellcomei Fraiha, Shaw & Lainson (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) em Fragmento de Mata Atlântica do Rio Grande do Norte, Nordeste do Brasil. Entomo Brasilis. 2013;2013(6):232–8.

Santos TV, Barata IR, Souza AAA, Silveira FT, Lainson R. First record of Lufzomyia termitophila Martins, Falcão and Silva (1964) and Lutzomyia hermanlenti Martins, Silva and Falcão (1970) (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Pará State, Brazil. Rev Pan-Amaz Saude. 2011;2:47–50.

Martins AV, Falcão AL, Silva JE. Estudo sobre os flebótomos do estado de Minas Gerais. VI: Descrição de “Lutzomyia termitophila” sp. n. e “Lutzomyia cipoensis” sp. n. (Diptera: Psychodidae). Rev Bras Biol. 1964;24:309–15.

Andrade Filho JD, Galati EAB, Falcão AL. Nyssomyia intermedia (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) and Nyssomyia neivai (pinto, 1926) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) geographical distribution and epidemiological importance. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:481–7.

Marcondes CB, Lozovei AL, Vilela JH. Distribuição geográfica de flebotomíneos do complexo Lutzomyia intermedia (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera, Psychodidae). Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31:51–8.

Lutz A, Neiva A. Contribuição para o conhecimento das espécies do gênero Phlebotomus existentes no Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1912;4:84–95.

Rangel EF, Souza NA, Wermelinger ED, Azevedo ACR, Barbosa AF, Andrade CA. Flebótomos de Vargem Grande, foco de leishmaniose tegumentar no estado do Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1986;81:347–9.

Pita-Pereira D, Alves CR, Souza MB, Brazil RP, Bertho AL, Barbosa AF, et al. Identification of naturally infected Lutzomyia intermedia and Lutzomyia migonei with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) revealed by a PCR multiplex non-isotopic hybridisation assay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:905–13.

Penha TA, Santos ACG, Rebêlo JMM, Moraes JLP, Guerra RMSNC. Fauna de flebotomíneos (Diptera: Pshychodidae) em área endêmica de leishmaniose visceral canina na região metropolitana de São Luís-MA. Biotemas. 2013;26:121–7.

Almeida PS, Minzão ER, Minzão LD, Silva SR, Ferreira AD, Faccenda O, et al. Ecological aspects of Phlebotomines (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the urban area of Ponta Porã municipality, State of Mato Grosso do Sul. Brazil Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:723–7.

Forattini OP. Entomologia Médica IV. In: Blucher E, editor. Psychodidae. Phlebotominae, Leishmaniose e Bartonelose, vol. VIII. São Paulo: Ltda; 1973. p. 658.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the scholarships to two of us (MNM and AAPF) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Maranhão (FAPEMA) for financial support to the study. We are grateful to the people in the communities of Barreirinhas and Santo Amaro who helped with setting up the light traps and collecting samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MNM, AAPF and JMMR conceived and designed the project, participated in the collection and analysis of data and drafted the manuscript. AAPF, MCAB, RSF, JLPM, CRGL and JMMR carried out field and lab work and participated in the collection and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1215-5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pereira Filho, A.A., Bandeira, M.d.C.A., Fonteles, R.S. et al. An ecological study of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the vicinity of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, Maranhão, Brazil. Parasites Vectors 8, 442 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1045-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1045-5