Abstract

Background

Cryptosporidium spp. have been extensively reported to cause significant diarrheal disease in humans and domestic animals. On the contrary, little information is available on the prevalence and characterization of Cryptosporidium in wild animals in China, especially in giant pandas. The aim of the present study was to detect Cryptosporidium infections and identify Cryptosporidium species at the molecular level in both captive and wild giant pandas in Sichuan province, China.

Findings

Using a PCR approach, we amplified and sequenced the 18S rRNA gene from 322 giant pandas fecal samples (122 from 122 captive individuals and 200 collected from four habitats) in Sichuan province, China. The Cryptosporidium species/genotypes were identified via a BLAST comparison against published Cryptosporidium sequences available in GenBank followed by phylogenetic analysis. The results revealed that both captive and wild giant pandas were infected with a single Cryptosporidium species, C. andersoni, at a prevalence of 15.6 % (19/122) and 0.5 % (1/200) in captive and wild giant pandas, respectively.

Conclusions

The present study revealed the existence of C. andersoni in both captive and wild giant panda fecal samples for the first time, and also provided useful fundamental data for further research on the molecular epidemiology and control of Cryptosporidium infection in giant pandas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Findings

Background

Cryptosporidium spp. are protozoan parasites that cause significant gastrointestinal disease in humans, domestic animals and wild vertebrates [1, 2]. Hosts get infected via the oral ingestion of oocysts that are excreted with feces by infected hosts [3]. Currently, delimiting species within the genus Cryptosporidium has also been controversial, but at least 27 Cryptosporidium species have been recognized as valid [4]. Of these, 14 species (over 30 Cryptosporidium genotypes) were known to infect wild animals, such as bears, lesser panda, raccoons, beavers, kangaroos, squirrels, monkeys, minks, mongooses, tortoise and finches [5–7].

The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) is one of the world’s most recognized and threatened wild animals with an estimated wild population size of only 1600. These individuals are restricted to six isolated mountain ranges in China, i.e. Minshan, Qionglai, Qinling, Daxiangling, Xiaoxiangling and Liangshan mountains. More precisely, they are mainly distributed in two of them --- Minshan (44.4 %) and Qiongla mountains (27.4 %) of Sichuan province [8]. To protect this endangered and valuable animal, several giant panda research bases, conservation centers and zoos have been established [8], raising 394 captive giant pandas, mostly in Sichuan province (85 %). Compared to the extensive studies on Cryptosporidium infection in humans and domestic animals hosts, fewer investigations have been conducted in wild animal species, especially in giant pandas. To date, only one Cryptosporidium infection case has been reported in an 18-year-old male captive giant panda in Sichuan province, China [9]. Moreover, there have been no large-scale Cryptosporidium prevalence studies of either wild or captive pandas in China. In order to gain more insight into the Cryptosporidium infection in giant pandas, we used molecular diagnostic tools to detect and characterize Cryptosporidium in both wild and captive pandas (approximately 31 % of the captive population) in Sichuan province, China.

Methods

Ethics statement

Samples were collected after defecation under the permission of the relevant institutions. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Wildlife Management and Animal Welfare Committee of China. During fecal collection, animal welfare was taken into consideration.

Fecal sample collection

Captive giant panda fecal samples (n = 122, each from one single animal) were obtained from two panda conservation centers (CRB: Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda; CCRC: China Conservation and Research Centre for the Giant Panda) in Sichuan province, China. Fecal samples (n = 200) from wild giant pandas were collected from four panda’s mountain habitats in Sichuan province during the 4th national investigation of giant pandas (Table 1). The samples were labeled and placed immediately in disposable plastic bags before being shipped to the laboratory of Sichuan Agricultural University for purification and processing.

Sample processing and DNA extraction

Oocysts were concentrated from feces as previously described [10]. Briefly, each fecal sample was mixed with 15 ml of dH2O in specimen cups. The suspension was then transferred to another clean specimen cup through a sieve with an 80 mm pore size to remove larger fecal debris. The filtrate was then centrifuged at 1800 × g for 15 min and the supernatant was removed. Total DNA was extracted from 200 mg of each oocyst precipitation using a QIAamp DNA Mini Stool Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The eluted DNA was stored at -20 °C prior to PCR analysis. DNA from Cryptosporidium obtained from a giant panda [9], kindly provided by the key laboratory of Animal Disease and Human Health of Sichuan Province, College of Veterinary Medicine, Sichuan Agricultural University, was used as a positive control, and deionized water was used as a negative control.

Gene amplification and sequencing

A PCR amplification approach was used to detect Cryptosporidium in DNA samples. We amplified a fragment (~830 bp) of the 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene as described previously [11]. During the PCR, the primer pairs (forward: 5′-TTCTAGAGCTAATACATGCG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCCATTTCCTTCGAAACAGGA-3′) were used. The PCR mixture contained 12.5 μl Taq PCR MasterMix (Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.), 0.5 μl BSA (0.1 g/10 ml), 8 μL ddH2O, 2 μL DNA and 1 μL of each forward and reverse primer (working concentration: 10pmol/L) in a 25 μl reaction volume. Each of the 35 PCR cycles consisted of 94 °C for 45 s, 59 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min after an initial hot start at 94 °C for 3 min and ending with 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were analyzed on a 1 % agarose gel and stained with GoldenView for visualisation. Because of the weakness of gel bands of interest, all the PCR products were purified and cloned into a pMD19-T vector before sent for commercial sequencing (Invitrogen, Shanghai).

Phylogenetic analysis

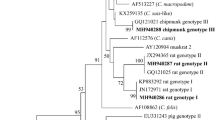

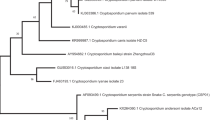

The obtained sequences were aligned with each other and published 18S rRNA gene sequences of Cryptosporidium spp. using the software ClustalX (http://www.clustal.org) to determine Cryptosporidium species. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium spp. were reconstructed using the Neighbour-Joining (1000 replicates) analysis implemented in MEGA 5.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) based on genetic distances calculated by the Kimura 2-parameter model. All the positive sequences (n = 20) generated from PCR analysis of the ~830 bp fragment of the 18S rRNA gene were used in the phylogenetic analysis. Eimeria tenella (GenBank accession number: U40264) was used as the out-group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using KF software (chi-square test, 1.0).

Results

A total of 322 fecal samples (122 captive ones and 200 wild ones) were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium by PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA gene. Of 122 fecal samples of captive pandas collected from conservation centers, 19 (15.6 %) were positive for Cryptosporidium infection (Table 1). Cryptosporidium was found across all gender and age groups (juvenile panda: 1.5–5.5 years, adult panda: >5.5 years [8]) of captive pandas (Table 2). Data showed that 21.9 % (15/73) of females and 14.3 % (4/49) of males were positive for Cryptosporidium, whilst 13.6 % (2/22) juvenile pandas and 17.0 % (17/100) adult pandas were identified as Cryptosporidium positive by PCR. However, these differences were not significant (different gender: P value = 3.45; different age: P value = 0.36).

Only one (0.5 %) sample from Minshan mountains was detected as Cryptosporidium positive out of all 200 fecal samples of wild pandas in Sichuan province (Table 1).

According to obtained phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), the Cryptosporidium isolates analyzed in this study cluster together with the strain described as C. andersoni (with 94.1–99.8 % identity) genotype originated from cattle. The nucleotide sequences of Cryptosporidium from giant pandas in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KJ696561 to KJ696580.

Discussion

Consistent with the previous study by Liu et al. [9], our results confirmed the presence of Cryptosporidium infection in captive giant pandas. Moreover, our findings demonstrated for the first time the presence of Cryptosporidium in wild giant panda fecal samples. Interestingly, phylogenetic analysis based on 18S rRNA gene, indicated that the Cryptosporidium isolate analyzed in this study clusters together with the strain described as C. andersoni (with 94.1–99.8 % identity) genotype originated from cattle, rather than recently reported genotype: the Cryptosporidium giant panda genotype (with 84.6–89.8 % identity). Notably, a distinct Cryptosporidium genotype and a different infection rate were observed in this study when compared to the previous investigation carried out in the same captive giant panda conservation center, i.e. CCRC. We propose that this might be due to the seasonal variation in the distribution of Cryptosporidium infection [2]. In our further studies, we will sample more fecal samples in different seasons of the year to determine the dynamics and full profiles of Cryptosporidium infection in giant pandas.

Regardless of the genotype, Cryptosporidium is a common parasite of wild mammals worldwide. Animals were exposed to Cryptosporidium after ingesting food or water that has been contaminated by infected feces [12]. Feng [13] reported that Cryptosporidium spp. infection rate in ungulates was 5.8 % (169/2896), 10.6 % (159/1506) in carnivores, 18.7 % (1937/10344) in wild rodents and 26.9 % (125/465) in primates [13]. In this study, the infection rate of Cryptosporidium observed in captive giant pandas (15.6 %) is higher than that observed in wild samples (0.5 %). This elevated captive infection rate may result from the relatively high density of captive housing and insufficient cleaned surfaces of the confined areas. High-density housing, to be more specific, is likely to not only increase the susceptibility of captive pandas to cryptosporidiosis, but also expose individuals to parasites that they would rarely encounter in the wild [14].

C. andersoni is the predominant species responsible for cryptosporidiosis in dairy and beef cattle [2]. The present observation revealed that adult pandas were more likely to be shedding C. andersoni, similar to previous studies that C. andersoni was more prevalent in yearling and adult cattle [15, 16]. In wild life, C. andersoni has been isolated from Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus), Bobak marmot (Marmota bobac), European wisent (Bison bonasus) [17], Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) [18] and lesser panda (Ailurus fulgens) [7]. Here, our results revealed the giant panda as a new host of C. andersoni and extended the range of host species known for this parasite. Although attention on zoonotic cryptosporidiosis has centered on other species such as C. parvm, C. meleagridis, C. felis and C. canis [2], previous studies showed that C. andersoni can infect humans under certain circumstances [19, 20]. Recently, C. andersoni was even identified as a novel predominant Cryptosporidium species in outpatients with diarrhea in China [21]. Due to the frequent contact of breeders, veterinarians and even tourists with captive giant pandas, the C. andersoni infections in captive giant pandas should be considered as a public health concern. The surveillance of the giant panda cryptosporidiosis is of great importance not only for veterinary medicine and researches but also for the public health concern.

Conclusions

The present study revealed the existence of C. andersoni infection in giant panda for the first time, expanding the range of recognized host species for this parasite. Moreover, this molecular investigation provided useful information for more in depth research on the molecular epidemiology and control of Cryptosporidium infection in giant panda in the future.

Abbreviations

- 18S rRNA:

-

18S ribosomal RNA

- CRB:

-

Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda

- CCRC:

-

China Conservation and Research Centre for the Giant Panda

References

Xiao L. Overview of Cryptosporidium presentations at the 10th International Workshops on Opportunistic Protists. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8(4):429–36.

Xiao L, Feng Y. Zoonotic cryptosporidiosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52(3):309–23.

Baldursson S, Karanis P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: review of worldwide outbreaks - an update 2004–2010. Water Res. 2011;45(20):6603–14.

Ryan U, Fayer R, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitology. 2014;141(13):1667–85.

Fayer R, Santin M, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium bovis n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in cattle (Bos taurus). J Parasitol. 2005;91(3):624–9.

Xiao L, Fayer R, Ryan U, Upton SJ. Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(1):72–97.

Wang T, Chen Z, Yu H, Xie Y, Gu X, Lai W, et al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in captive lesser panda (Ailurus fulgens) in China. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(2):773–6.

Zhang ZH, Wei FW. Giant Panda: Ex-Situ Conservation Theory and Practice. Beijing: Science Press; 2006.

Liu X, He T, Zhong Z, Zhang H, Wang R, Dong H, et al. A new genotype of Cryptosporidium from giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in China. Parasitol Int. 2013;62(5):454–8.

Current WL. Techniques and laboratory maintenance of Cryptosporidium. In: Dubey JR, Speer CA, Fayer R, editors. Cryptosporidiosis of man and animals. Boca Raton: CRC; 1990. p. 59–82.

Xiao L, Escalante L, Yang C, Sulaiman I, Escalante AA, Montali RJ, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65(4):1578–83.

Alves M, Xiao L, Lemos V, Zhou L, Cama V, da Cunha MB, et al. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in mammals and reptiles at the Lisbon Zoo. Parasitol Res. 2005;97(2):108–12.

Feng Y. Cryptosporidium in wild placental mammals. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124(1):128–37.

Lim YA, Ngui R, Shukri J, Rohela M, Mat Naim HR. Intestinal parasites in various animals at a zoo in Malaysia. Vet Parasitol. 2008;157(1–2):154–9.

Santin M, Trout JM, Xiao L, Zhou L, Greiner E, Fayer R. Prevalence and age-related variation of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in dairy calves. Vet Parasitol. 2004;122(2):103–17.

Langkjaer RB, Vigre H, Enemark HL, Maddox-Hyttel C. Molecular and phylogenetic characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from pigs and cattle in Denmark. Parasitology. 2007;134(Pt 3):339–50.

Ryan U, Xiao L, Read C, Zhou L, Lal AA, Pavlasek I. Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from the Czech Republic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(7):4302–7.

Koudela B, Modry D, Vitovec J. Infectivity of Cryptosporidium muris isolated from cattle. Vet Parasitol. 1998;76(3):181–8.

Leoni F, Amar C, Nichols G, Pedraza-Diaz S, McLauchlin J. Genetic analysis of Cryptosporidium from 2414 humans with diarrhoea in England between 1985 and 2000. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 6):703–7.

Morse TD, Nichols RA, Grimason AM, Campbell BM, Tembo KC, Smith HV. Incidence of cryptosporidiosis species in paediatric patients in Malawi. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(8):1307–15.

Jiang Y, Ren J, Yuan Z, Liu A, Zhao H, Liu H, et al. Cryptosporidium andersoni as a novel predominant Cryptosporidium species in outpatients with diarrhea in Jiangsu Province China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:555.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Science & Technology Ministry, China (No. 2012CB722207) and the Research Fund for the Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding (No. CPF-2012-13). We would like to thank Yike Kang for comments on the draft manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GY and RH conceived the concept of the project. ZC, QW, XG, WL and XP collected samples. ZC performed the lab work. TW and XY carried out the data analysis. TW wrote this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Tao Wang and Zuqin Chen contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Chen, Z., Xie, Y. et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in Sichuan province, China. Parasites Vectors 8, 344 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0953-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0953-8