Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a psychosocially impairing and cost-intensive mental disorder, with first symptoms occurring in early childhood. It can usually be diagnosed reliably at preschool age. Early detection of children with ADHD symptoms and an early, age-appropriate treatment are needed in order to reduce symptoms, prevent secondary problems and enable a better school start. Despite existing ADHD treatment research and guideline recommendations for the treatment of ADHD in preschool children, there is still a need to optimise individualised treatment strategies in order to improve outcomes. Therefore, the ESCApreschool study (Evidence-Based, Stepped Care of ADHD in Preschool Children aged 3 years and 0 months to 6 years and 11 months of age (3;0 to 6;11 years) addresses the treatment of 3–6-year-old preschool children with elevated ADHD symptoms within a large multicentre trial. The study aims to investigate the efficacy of an individualised stepwise-intensifying treatment programme.

Methods

The target sample size of ESCApreschool is 200 children (boys and girls) aged 3;0 to 6;11 years with an ADHD diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) or a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) plus additional substantial ADHD symptoms. The first step of the adaptive, stepped care design used in ESCApreschool consists of a telephone-assisted self-help (TASH) intervention for parents. Participants are randomised to either the TASH group or a waiting control group. The treatment in step 2 depends on the outcome of step 1: TASH responders without significant residual ADHD/ODD symptoms receive booster sessions of TASH. Partial or non-responders of step 1 are randomised again to either parent management and preschool teacher training or treatment as usual.

Discussion

The ESCApreschool trial aims to improve knowledge about individualised treatment strategies for preschool children with ADHD following an adaptive stepped care approach, and to provide a scientific basis for individualised medicine for preschool children with ADHD in routine clinical care.

Trial registration

The trial was registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) as a Current Controlled Trial under DRKS00008971 on 1 October 2015. This manuscript is based on protocol version 3 (14 October 2016).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a highly prevalent, early-onset, persistent neurodevelopmental disorder, which is associated with psychosocial functional impairment and a markedly reduced subjective health-related quality of life [1,2,3]. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) criteria, it is characterised by age-inappropriate, pervasive and persistent inattentiveness, impulsivity and/or motor restlessness [4, 5]. ADHD symptoms can be observed as early as the preschool years, with an estimated prevalence of 1.5–6% among preschool children [6, 7]. For the diagnosis of ADHD, clinically relevant functional impairment must be present in different settings, e.g. in the family and at preschool. In addition, comorbidity in preschool children with ADHD is common, with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), communication disorder and anxiety disorders being the most prevalent comorbid conditions [8]. Early interventions have been shown to be particularly helpful and might prevent the development of secondary symptoms as well as school failure [9,10,11]. International and national treatment guidelines [12,13,14] recommend a combination of multiple, individually adapted treatment components (i.e. multimodal therapy). However, compared with school-age children, treatment with immediate-release methylphenidate has been shown to be less effective in preschool children (i.e. effect sizes were considerably smaller), to cause more adverse events and to be less accepted by parents [15]. In contrast, psychosocial treatment may be most powerful at this early age, as it can positively influence parental scaffolding during early self-regulation development and prevent the development of coercive cycles of negative parent-child interactions. Accordingly, clinical guidelines recommend psychosocial interventions in the family and the preschool as the treatment of choice for preschool children with ADHD [12,13,14].

Parent counselling and parent management training have been found to be effective treatments for children of this age group [12, 16, 17]. Recent meta-analyses on the efficacy and effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in preschool children with disruptive behaviour disorders (DBD), including ADHD, showed medium to large effects on child behaviour outcomes. Based on 13 studies, Charach et al. [18] found a moderate overall effect (standardised mean difference [SMD] = 0.75) of parenting training on parent-reported DBD symptoms; the effect size for core symptoms of ADHD was SMD = 0.77 (five included studies). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 36 randomised control trials (RCTs) on a broader range of psychosocial interventions resulted in a large overall effect on parent-, teacher- and observer-reported DBD symptoms (Hedges’ g = 0.82) and a medium effect (g = 0.61) on hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms in particular [19]. The analysis included behavioural and non-behavioural treatments, with the former showing significantly larger effects [19] . Even though clinical guidelines recommend preschool interventions, so far, preschool teacher training as well as preschool-based interventions are rare. The Cologne group led by Döpfner reported that their indicated prevention programme addressing preschool teachers was effective [9, 20, 21]. The measured effects were largely maintained at 1-year follow-up (e.g. [9, 22]).

However, previous studies in preschool children with ADHD are subject to some limitations. For instance, the evidence regarding the value of these interventions is limited to unblinded ratings made by individuals who are likely to be invested in the treatment success. Evidence of efficacy from well-controlled trials using blinded assessments of outcomes is still lacking [23]. Furthermore, the validity of the available RCTs is limited by the design characteristics, as most of the RCTs used no treatment as a control condition, rather than treatment as usual (TAU) or non-specific support. Therefore, some of these results cannot be generalised [18, 19].

Another critical issue in the treatment of preschool children with ADHD is that unfortunately, not all parents are willing or able to procure treatment for their children. Frequent reasons why parents do not start or complete interventions include a lack of problem awareness, a lack of availability of psychotherapy, or other problems such as transport, childcare, work commitments, financial burden, or stigma (e.g. [24, 25]). Besides and despite these treatment barriers, the need for intervention still exceeds the number of available treatment options, and treatment resources are sparse [24]. Therefore, it is important to focus on therapies and dissemination methods that help to overcome these barriers. There is evidence that self-directed, bibliographic interventions and telephone- or web-based assistance might be one way forward [18, 26, 27]. Self-directed interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing parent-rated externalising behaviour problems [28, 29]. Some studies indicate that the effects of such interventions may be improved by minimal therapeutic support (e.g. by telephone; see [28]). For example, Kierfeld et al. [30] successfully demonstrated the effects of a telephone-assisted self-help (TASH) intervention for parents of preschool children with ADHD and other externalising behaviour problems. The effects were maintained at 1-year follow-up [31]. An effectiveness study on a TASH intervention for parents of 6–12-year-old children with ADHD found a significant reduction of ADHD and comorbid symptoms under routine care conditions [32]. Moreover, TASH for parents was found to enhance effects of methylphenidate treatment in a sample of children with ADHD [33]. Interestingly, behavioural and non-behavioural TASH interventions seem to have similar effects [34].

An open research question is which of the different treatment components (e.g. behaviour therapy, self-directed interventions) should be offered following obligatory psychoeducation, and in which order. In this respect, a stepped care approach in which treatment is individually adapted according to symptom strength, comorbid symptoms, specific family needs and treatment response is suggested [12]. However, empirical evidence for the efficacy of adaptive treatment strategies for patients with an ADHD diagnosis in general, and in preschool children in particular, is sparse. A study assessing an adaptive multimodal treatment in school-age children found that both behaviour therapy and a combination of behaviour therapy and pharmacotherapy are effective in the treatment of ADHD [35], with effects persisting at an 18-month follow-up [36]. Whereas the efficacy of different singular interventions is also well documented in preschool children, a stepwise approach with individualised adaptive treatment strategies has not been empirically validated for this age group. Therefore, a stepped care approach for 3–6-year-old preschool children is being evaluated within the trial ESCApreschool (Evidence-Based, Stepped Care of ADHD in Preschool Children aged 3 years and 0 months to 6 years and 11 months of age (3;0 to 6;11 years). The results aim to improve the knowledge about individualised treatment strategies for preschool children with ADHD. The evaluation of a stepwise approach in routine care is of particular importance for clinical practice.

Methods and Design

ESCApreschool is part of a multicentre consortium studying stepped care approaches for the treatment of ADHD along the lifespan (ESCAlife: Evidence-Based Stepped Care of ADHD along the Lifespan, coordinator Tobias Banaschewski). ESCAlife encompasses stepped care designs in different age groups (preschool age, school age, adolescents, adults), each focusing on the different specific needs in the respective life phases, including 6–12-year-old school children (ESCAschool [37]), 12–17-year-old adolescents (ESCAadol [38]) and 16–45-year-old adults (ESCAlate [39]). With regard to design and methodology, the single studies overlap to allow for the examination of selected research questions across all age groups.

Objectives, study design and trial flow

ESCApreschool aims to examine the efficacy of an individualised stepwise-intensifying treatment approach based on evidence-based behavioural interventions in patients with ADHD or patients with ODD and additional ADHD symptoms, aged 3;0 to 6;11 years, who attend preschool. Different treatment strategies are investigated for children who respond to a low-threshold TASH intervention and those who do not. A further question is to determine precisely which families benefit from the low-threshold TASH intervention or more intensive behaviour therapy and which families do not, and to identify the predictors and moderators of treatment response. Therefore, the secondary objective is to examine the predictability of treatment response by psychological and biological variables.

The multicentre study is designed as a stepwise (two steps) adaptive treatment study including two RCTs. In the adaptive design, the second step of the trial (step 2) depends on the outcome of step 1.

Step 1 of the ESCApreschool study consists of a randomised waitlist-controlled trial which provides the parents (and optionally also the preschool teachers) of the participating children (planned number of N = 200 children) with a 3-month TASH intervention. The parents (and preschool teachers) are randomised to receive this treatment either immediately at the beginning of the trial or after a 3-month waiting period.

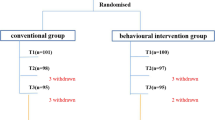

The intervention provided in step 2 of the trial depends on the outcome of the low-threshold TASH intervention. If children fully respond to this intervention, their parents (and preschool teachers) receive TASH booster sessions in step 2. If children do not or only partially respond to TASH, that is, if they show persisting ADHD and/or ODD symptoms, they are randomised to receive either parent management and preschool teacher training (PMPTT) or TAU. For an overview of the trial flow, please refer to Fig. 1.

Flow chart. ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder, T0 to T4 = Assessment Time Points; R = Randomisation; TASH = Telephone-Assisted Self-Help for Parents and Preschool Teachers; PMPTT = Parent Management and Preschool Teacher Training, TAU = Treatment as Usual, Booster SH = Booster Self-Help

The sample sizes and response rates displayed in the figure are estimations and therefore differ from the actual recruitment and response rates.

Step 1 lasts for 3–6 months depending on the allocation of the participants (3 months in the TASH group; 6 months in the waiting control group, which undergoes a 3-month waiting period followed by the 3-month TASH intervention period). Step 2 lasts for 6 months, and the follow-up period lasts for 3 months.

Measurements are taken at T0 and T1 (T0 = screening of inclusion and exclusion criteria and assessment of ADHD and ODD criteria; T1 = baseline assessment as described below). Further measurements ensue after step 1 (T2), after the second treatment phase in step 2 (T3), and 3 months after the end of the treatment (follow-up examination; T4). Families who are randomised to the waiting control group take part in an additional assessment after the waiting period (T2b1). Participants who discontinue the intervention during one of the treatment phases are also invited for the follow-up assessment (T4) in order to monitor their development. Additionally, data are collected during the therapeutic process.

Clinical assessments of ADHD and ODD symptom severity are completed by trained experienced clinicians (further referred to as “blinded clinicians”), who are blind to the patients’ assignment to treatment condition but not to the assessment time point (T1-T4). The inclusion of participants into the study, as well as their classification as full responders or partial/non-responders to step 1, are based on these clinical interviews. For validation purposes, all interviews are recorded and a subsample of the recordings is subsequently rated by a clinician who is blind to both the treatment condition and the assessment time point.

Trial sites

At the start of the study, a total of six trial centres located at departments of child and adolescent psychiatry at university hospitals in Germany (Cologne, Hamm, Mannheim, Marburg, Tübingen, Würzburg) contributed to this multicentre trial.

The leading and coordinating centre of the ESCApreschool study is Marburg (Principal Investigator [PI] Katja Becker). Each of the six centres was expected to enrol between 30 and 40 patients in order to achieve a total sample size of N = 200 patients. To compensate for low recruiting numbers, three additional trial centres were included in 2018 (Aachen [Kerstin Konrad], Göttingen [Luise Poustka], Neuruppin [Michael Kölch]).

The TASH work group at the Cologne University Hospital (Manfred Döpfner, also Co-PI of ESCApreschool) is responsible for delivering TASH (which is provided centrally from Cologne for all participants). All other diagnostic procedures and treatments are provided at the respective study centres. On-site therapists who have been trained and who are supervised by the Cologne work group perform the behaviour therapy. Responsibility for data management, archiving and monitoring, as well as biometrics and project management, lies with the Centre for Clinical Studies in Freiburg.

Participants

A total of 200 girls and boys, aged 3;0 to 6;11 years, with either a diagnosis of ADHD or substantial ADHD symptoms combined with a diagnosis of ODD are the study’s target group. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1 (see Measures section for a more detailed description of the instruments). These data are assessed at baseline through an interview gathering baseline characteristics as well as sociodemographic data. Patients are recruited through the centres’ outpatient clinics, which are highly experienced in the treatment of ADHD or preschool children. Further recruitment strategies include the dissemination of information regarding the study at local conferences, and by contacting paediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, child and adolescent psychologists and child guidance centres. Additionally, information is provided to other counselling centres, ADHD self-help groups and preschool teachers either in writing, in person, or through lectures. In Germany, the local health authorities organise a mandatory health examination for preschool children shortly before school entry. Therefore, the respective local health authorities are also informed about the study. All of these recruitment activities are flanked by homepage information, local public lectures and repeated advertisement actions providing information about the study (postings, flyers, bus advertisements, newspaper articles) in order to reach parents directly.

*Some changes have been made since the first version of the study protocol (9 June 2015). First, we initially planned an age span of 3;0 to 5;11 years. However, this resulted in the exclusion of 6-year-olds who were still attending preschool within the overall ESCAlife study. Thus, this inclusion criterion was changed to 3;0 to 6;11 years (Note to File G005 22 September 2016, positive Ethics Committee vote 08 November 2016). Second, the first version of the study protocol comprised an additional inclusion criterion of a time span from at least 9 months before enrolment in primary school. Due to recruitment problems, this criterion was changed to “attending preschool” (Note to File G003 25 May 2016; positive Ethics Committee vote 3 June 2016). Third, an inclusion criterion in the first version of the trial protocol was the presence of an ADHD diagnosis according to DSM-5, assessed with a clinician-rated ADHD checklist (DCL-ADHS). However, after study start, we realised that at preschool age, the differentiation between a diagnosis of ADHD and a diagnosis of ODD plus additional ADHD symptoms might be blurred. Therefore, this inclusion criterion was changed to that mentioned in the table (Note to file G002, 25 May 2016, positive Ethics Committee vote 3 June 2016).

Fourth, the initial inclusion criterion “informed consent of preschool teacher” was withdrawn due to the fact that in some centres, it was not permitted to contact preschool teachers directly. Therefore, in the present version of the study protocol, while it is preferable to include a preschool teacher in the study (if parents agree to their being contacted), this is not a prerequisite or an inclusion criterion (Note to File G003 25 May 2016; positive Ethics Committee vote 3 June 2016). Fifth, initially, an exclusion criterion was “current medication for ADHD or other psychotropic medication”. After realising that this exclusion criterion leads to an exclusion of severe cases with a current ADHD medication, this criterion was changed to “psychotropic medication of the child (except for ADHD medication)” (Note to File G003 25 May 2016, positive Ethics Committee vote 3 June 2016).

This table gives the inclusion and exclusion criteria of Version 3 of the Trial Protocol (V03, 14. October 2016) including all amendments G001-G005.

** The comorbid conditions which are defined as exclusion criteria are the same as those for the different trials within the ESCAlife consortium, including some diagnoses which are unlikely to appear at preschool age.

Patients are included if they meet the eligibility criteria (see Table 1). Parents (and, if applicable, preschool teachers) must give their informed consent and children their assent for study participation.

Response criteria

The response criteria correspond to the child’s symptom inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Partial or non-responders have ADHD (DSM-5) assessed with the clinician-rated ADHD Checklist (DCL-ADHS) or ODD (DSM-5) assessed with the clinician-rated ODD Checklist (DCL-SSV) plus substantial ADHD symptoms (defined by a score of ≥ 0.7 on either of the two subscales [hyperactivity/impulsivity or inattention] of the DCL-ADHS). Full responders fulfil neither of these conditions and no longer have ADHD or ODD with substantial ADHD symptoms.

Data handling

All legal requirements pertaining to the protection of personal data have been met. Upon enrolment, every participating child is assigned with a study-specific identification code. To ensure complete pseudonymisation, all study data from patients and their parents are stored under their assigned code. This is not shared, with the sole exception of transmission of contact details to members of the Cologne group providing the TASH intervention, following consent from participating parents. Only the PI and the study coordinators at each site have access to the patient identification list. The Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) Freiburg provides an electronic remote data entry system (RDE-LIGHT), in which information is entered by specifically trained personnel under the study code. To prevent unauthorised access to confidential participant information, built-in security features encrypt all data before transmission to and from the CTU. Users who enter data into the system are registered with the CTU and receive an individual ID and password to gain access to the system, in order to prevent unauthorised access to patient data. Data processing at the CTU is limited to authorised personnel who are familiar with the data handling procedures according to the study protocol.

Interventions

Telephone-assisted self-help (TASH)

In step 1, all participants receive a 3-month behaviour therapy-oriented TASH intervention for parents of children with externalising behaviour problems. Additionally, if both the parents and the preschool teacher agree, preschool teachers also receive the intervention [40, 41]. The intervention is based on the Therapy Programme for Children with Hyperactive and Oppositional Problem Behaviour (Therapieprogramm für Kinder mit hyperkinetischem und oppositionellem Problemverhalten – THOP [42]) and the German self-help book Wackelpeter & Trotzkopf [43]. Both the parent and the preschool teacher programme consist of self-help booklets on externalising behaviour problems and behaviour modification techniques, which are sent to the participants through the post. Additionally, they receive telephone consultations with a therapist in advanced training for child and adolescent psychotherapy, who is supervised by senior supervisors. These consultations serve to support the parents and preschool teachers with the implementation of the interventions into their daily routines [40, 41].

Parent TASH programmes similar to that used in the present study have already been shown to reduce behaviour problems in preschool- and school-age children (e.g. [30, 32,33,34]). For the current study, the parent booklets were revised and adapted to address the specific needs of families of preschool children. The parents receive eight booklets and ten telephone consultations, each lasting for approximately 30 minutes. The TASH programme for the preschool teachers consists of four newly developed booklets and four telephone consultations of up to 60 minutes each. The appointments for the telephone consultations are set on an individual basis. The contents of the booklets are described in Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1.

For the preschool teachers, the interventions originally developed for the family environment have been adapted to the preschool environment. Moreover, the booklets for the preschool teachers cover information on improving environmental conditions, which might help the child to deal with his or her behaviour problems, and on constructive cooperation with parents (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

If children are full responders to the TASH intervention, two additional telephone consultations for the parents and, optionally, one additional telephone consultation for the preschool teacher are provided (Booster TASH).

Parent management and preschool teacher training (PMPTT)

For children with no or only partial response to TASH, who are randomised to the PMPTT group, age-appropriate individually tailored behaviour therapy is provided in step 2. The 6-month PMPTT encompasses (1) parent management training, including parent-child interaction training, (2) preschool-teacher-focused interventions, including psychoeducation and behavioural interventions in the preschool, and (3) child-focused interventions (see Table 3). The primary goal of PMPTT is to reduce child problem behaviour and to enhance the parent-child and teacher-child relationship by improving parents’ skills and teachers’ educational skills. A total of 20 weekly sessions are provided. Parent- and teacher-focused interventions are based on the THOP [42] and on the PEP (Prevention Programme for Externalising Problem Behaviour; Präventionsprogramm für Expansives Problemverhalten - PEP [44]). Child-focused interventions are based on the Therapy Programme for the Improvement of Organisational Skills, Concentration and Impulse Control in Children with ADHD (Therapieprogramm zur Steigerung von Organisationsfähigkeit, Konzentration und Impulskontrolle bei Kindern mit ADHS – THOKI-ADHS [45]). THOP is the only German treatment programme for ADHD with established efficacy [42]. PEP has been extensively evaluated in several trials with preschool children with externalising problem behaviour [9]. The PEP programme was originally developed for the training of parents and teachers of preschool children in a group format. For ESCApreschool, PEP materials were adapted for use in an individual format. PMPTT is conducted by clinical therapists who are trained during a 2-day workshop (see section on Treatment integrity).

Treatment as usual (TAU)

The other group of partial or non-responders to TASH receives TAU in step 2, that is, a typical, mostly guideline-based ADHD preschool intervention. TAU is usually conducted by the participating centres but may also be performed by local cooperating institutions (e.g. child guidance centres, ergo−/occupational therapy, child and adolescent psychiatrists, psychotherapists). In the latter case, members of the cooperating institutions are asked to provide information about their treatment. To achieve a minimum of conformity, at least four patient contacts within the treatment period of 6 months are recommended.

Starting or optimising an additional ADHD pharmacotherapy (according to the clinical decision of the treating physician) is permitted in step 2 in the TAU condition as well as in the PMPTT condition, but has to be documented.

Treatment integrity

Treatment integrity is established through qualification standards for therapists (therapists have completed a university degree qualifying for training to become a licensed child and adolescent therapist, and are currently in training for psychotherapy with children and clinical expertise in the treatment of ADHD), study-specific therapist training, the use of the manualised treatment programmes and the use of protocol sheets for treatment documentation. TASH and PMPTT treatments are supervised by senior supervisors to check for adherence to the manual and study procedures. PMPTT therapists participate in three supervision sessions per patient. These sessions are scheduled after therapy sessions 5, 10 and 15, and are conducted either face to face or by telephone. For each patient, at least two video sequences are discussed with the supervisor. The TASH consultations are recorded in audio files and supervised regularly.

Informants

ESCApreschool collects information from different perspectives and informants: unblinded clinician (e.g. therapist or TASH counsellor), blinded clinician, the participating parent, the other parent/partner of participating parent, and, optionally, the preschool teacher.

The blinded clinicians conduct the clinical interviews with the parents, and are blind to the study condition. However, in order to minimise heterogeneity in ratings caused by different assessors, the same clinician should perform the interviews with a family at the different assessment time points. Therefore, the blinded clinicians are not blind to the assessment time point.

Additionally, to control for inter-rater reliability, the ratings of the parent interviews are audio- or videotaped. A clinician who is blind to both the treatment condition and the assessment time point rates a random selection of these interviews. The parent is the biological parent or guardian of the child, who is involved in the treatment (he or she is therefore not blind to the treatment condition). If possible, ratings by the child’s preschool teacher are obtained.

Measures

Main assessment time points

Unless otherwise stated, the primary and secondary outcome measures are assessed at all four main assessment time points (T0/T1, T2, T3, T4). Figure 2 gives an overview of the measures assessed at the different time points.

Additional file 2: Figure S1 presents the time schedule in greater detail, with an overview of outcome measures, predictors and eligibility criteria.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome is the change in the combined ADHD and ODD symptom score. This combined symptom score is derived from the blinded clinician-rated ADHD and DBD Symptom Checklists based on a parent interview (DCL-ADHS + SSV Parent [46]). The DCL-ADHS and the DCL-SSV assess symptoms of ADHD or ODD and conduct disorder, respectively, according to DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria. The DCL-ADHS consists of 18 items assessing ADHD symptoms and five items assessing functioning and psychological strain. The items on ADHD symptoms can be aggregated into two scales, inattention (nine items) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (nine items). The DCL-SSV comprises 28 items belonging to four subscales: ODD (eight items), aggressive-dissocial problem behaviour (seven items), limited prosocial emotionality (11 items), and disruptive mood disorder (five items, three of which are also part of the ODD scale). For ESCApreschool, we excluded the scale assessing disruptive mood disorder, as the associated symptoms are uncommon in preschool children. Moreover, the DCL-SSV includes five items on functioning and psychological strain. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. Scale scores are computed by averaging the associated item scores. The DCL-ADHS and the DCL-SSV subscales and total scores show satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > .68 [46, 63].

We use a combined score of ADHD and ODD, since the two conditions are highly correlated in preschool children with ADHD, and the reduction of symptoms of ADHD and ODD is usually the main objective of treatments in this age group.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures assess (1) ADHD and DBD symptoms as rated by parents and teachers, (2) psychosocial impairment, (3) comorbid symptoms and comorbid mental disorders, (4) quality of life of the child as perceived by parents, (5) social reactivity, and (6) parenting behaviour. All instruments used to assess symptoms and impairment are recommended in diagnostic guidelines for ADHD [12] and are employed in clinical practice. All secondary outcome measures have been validated both in English and in German and have been used in previous trials of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions as well as in prevention studies. They have been widely used in children, and especially in preschool children with ADHD. All instruments provide population-based norms and therefore enable the calculation of age- and gender-adjusted normalisation rates.

ADHD and DBD symptoms

Parents and preschool teachers rate the symptom severity of ADHD and DBD on the ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scale for Preschool Children (FBB-ADHS-V; German: Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Vorschulkinder mit Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit−/Hyperaktivitätsstörungen [46]) and on the DBD Parent and Teacher Rating Scale (FBB-SSV; German: Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Störungen des Sozialverhaltens). The scales capture symptoms of ADHD or DBD, respectively, according to ICD-10 and DSM-5. The FBB-ADHS-V consists of 19 items belonging to the subscales inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. In the version for younger children (up to the age of 11), the FBB-SSV comprises 27 items, which can be aggregated into four subscales: ODD, aggressive-dissocial problem behaviour, limited prosocial emotionality, and disruptive mood disorder. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. Scale scores are computed by averaging the associated item scores. The subscales and the total score of both the FBB-ADHS and the FBB-SSV have demonstrated reliability and factorial validity.

Clinical global impression and functional impairment

The clinician-rated Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) is administered using a short clinical interview [47]. It is a widely used outcome parameter in clinical trials, measuring disease severity (CGI-severity, CGI-S) as well as general improvement during treatment (CGI-improvement, CGI-I). Both the CGI-S and the CGI-I are rated on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity or improvement, respectively. The CGI shows a good inter-rater reliability (.65–.92 [64];) and an intra-class correlation coefficient of .91 [65].

A German version of the parent-rated Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale, which was modified and adapted for use in preschool-age children, is applied to measure functional impairment [66, 67]. The modified German version consists of 40 items, which are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate greater impairment. The subscales and total score of the original version and of the modified German version have shown internal consistency (α > .80) and factorial validity [66,67,68]. Moreover, the original version has demonstrated test-retest reliability, convergent validity, and responsiveness to change [68].

Comorbid internalising and externalising symptoms

The German version of the parent-rated Child Behavior Checklist 1½-5 (CBCL 1½-5 [69];; original English version: [70]) and the preschool teacher-rated Caregiver-Teacher Report Form 1½-5 (C-TRF 1½-5; Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist, 2002b; original English version: [70]) are questionnaires to assess behavioural problems, emotional problems and somatic complaints of toddlers and preschool children aged 1½ to 5 years. Both scales comprise 99 items (83 overlapping items) rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 to 2. The items can be aggregated into several syndrome scales as well as into three superordinate scales: internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and total problems. These superordinate scales are considered in ESCApreschool. For both the CBCL and the C-TRF, these scales have demonstrated satisfactory internal consistencies (α > .80) in German samples [69]. Moreover, analyses in German samples have provided evidence for the construct validity of the CBCL as well as limited evidence for the factorial validity of the CBCL internalizing problems and externalizing problems scales [69].

Quality of life

In evaluating health care with respect to prevention and treatment, quality of life has emerged as an important concept. We use the Kiddy-KINDL [53, 71, 72] to assess subjective generic health-related quality of life in preschool children. Results on the reliability of this scale vary: In a sample of preschoolers aged 4–6 years, Cronbach’s alpha for the total score varied from .66 to .70 depending on age and gender [72]. However, in a larger sample of 3–6-year-old children, a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 was reported [73].

Callous-unemotional traits and social responsiveness

Callous-unemotional traits are assessed with five items of the prosocial behaviour scale and the peer problems scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ [74]) and three items of the callous-unemotional dimension of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD-CU [75], which were combined into a joint measure. The items are rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 to 2. Pasalich et al. [51] also combined items of the SDQ and the APSD, but used more items. They found satisfactory internal consistencies across mother, father and child ratings of their measure (range of α = 0.69–0.87).

Social responsiveness is assessed using a shortened 16-item version of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-short [76]). The items of this questionnaire are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The long version of the SRS shows high internal consistency (α = 0.91–0.97) as well as satisfactory test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, convergent validity and discriminative validity [60].

Parenting behaviour

Positive parenting behaviour is assessed using a German questionnaire covering positive parenting skills (Fragen zum Erziehungsverhalten, FZEV; Naumann, Kuschel et al., 2007). This questionnaire comprises 13 items rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more positive parenting behaviour. The scale shows satisfactory internal consistency (mother ratings: α = 0.85; father ratings: α = 0.87 [77]). For the assessment of negative parenting behaviour, we apply the respective 13-item scale of the Questionnaire on Positive and Negative Parenting Behaviour (German: Fragebogen zum positiven und negativen Erziehungsverhalten, FPNE [55]). The items of this scale are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating more negative parenting behaviour. The scale is internally consistent (α = 0.78).

Additionally, to assess parents’ perceived sense of competency concerning challenging parenting situations, we employ a modified German Version of the Problem Setting and Behaviour Checklist (German: Verhalten in Risikosituationen, VER [77]). The 27 items of this questionnaire are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating a stronger sense of competency. The scale has demonstrated high internal consistency (mother ratings: α = 0.92, father ratings: α = 0.94 [77]).

Treatment satisfaction

For the assessment of satisfaction with the treatment, treatment-specific parent satisfaction questions were developed (e.g. for the assessment of satisfaction with TASH). These are assessed as part of the clinical interview at T2 and T3.

Feasibility and adherence measures

Besides the outcome measures used at all of the main assessment time points (T1 to T4), the following measures are used to assess feasibility and adherence:

- (1)

Clinical Feasibility Rating Scale (newly developed) to rate the feasibility of the TASH and PMPTT interventions (at T2 and T3);

- (2)

Clinical Adherence Rating Scale (newly developed) to assess the adherence of the patient, the parents and preschool teachers during the interventions (at T2 and T3).

Assessment of potential moderators of treatment response

The following potential moderators of treatment response are analysed: (1) age, (2) gender, (3) socioeconomic status, (4) ADHD symptom severity, (5) comorbid symptoms, (6) intelligence, (7) parental depression, anxiety and stress (Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, DASS; Cronbach’s α = 0.89–.96, test-retest reliability r = 0.71–.81, validity [57, 78]), and (8) parental ADHD (ADHD Self-Rating Scale, German: ADHS-Selbstbeurteilungsskala, ADHS-SB; test-retest reliability r = 0.78–.89; Cronbach’s α = 0.72–.9, validity [62, 79]).

Psychometric data

The following variables are assessed using a clinical interview with the parent during the diagnostic assessment at T0 and T1 and considered as possible predictors of treatment outcome: sociodemographic data of the child and the parent (e.g. child age, educational level of the parent or guardian), data on early child development (six items), temperament (13 items; Junior Temperament and Character Inventory [JTCI] 3–6 [59]), irritability (seven items; Affective Reactivity Index [ARI-Parent] [80]), and life events (14 items). Additionally, we employ the German version of the Family Adversity Index (FAI), adopted from the German Mannheimer Elterninterview [81]; original English version: [82, 83]). To measure parental aggression, we use the anger control scale of the German Elternfragebogen zum Umgang mit Ärger (FB-Ä) [Götz-Dorten, A. (unpublished) 2013; Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne], which is a modified version of the 12-item form of the Aggression Questionnaire [84, 85]. The clinical checklist Diagnose-Checkliste zum Screening psychischer Störungen (DCL-SCREEN; taken from the DISYPS-III [46]) is used to assess comorbid symptoms of depression (seven items), anxiety (ten items), autism spectrum disorder (four items), other neurodevelopmental disorders (six items), obsessive-compulsive disorder (two items) and tic disorders (one item). Based on a modified questionnaire by Piacentini et al. [86], the therapists additionally report their expectation of treatment benefit (three items) for a family. Moreover, the participating parents provide information about their own treatment expectations.

Furthermore, after every therapy session of step 1 and step 2, the therapist rates the treatment integrity (13 self-developed items), the treatment adherence of the client (ten items; eight items for TASH only), and current ADHD symptoms of the child (four items; shortened version of the German ADHD Questionnaire [87].

At the beginning of the study (T0/T1), children complete four subtests of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI-III) to assess their IQ [49]. The 3-year-old children work on the scales Receptive Vocabulary, Comprehension, Block Design and Object Assembly, while the 4–6-year-olds complete the subtests Word Reasoning, Vocabulary, Matrix-Reasoning and Block Design.

Biological data

Transcranial sonography (TCS) is used to assess biological predictors of treatment response, especially in younger children. This is part of the transversal project ESCAbrain, which assesses biological data in all ESCAlife trials (see also [37,38,39]). Using TCS, the size of the echogenic region of the substantia nigra is assessed. In children, ADHD-associated hyperechogenicity of the substantia nigra has consistently been reported and has previously been identified as a potential biological marker of ADHD [88, 89]. TCS is a non-invasive method for the visualization of deep brain structures, such as the substantia nigra, through the intact skull. Ultrasound waves are reflected depending on tissue composition, resulting in different echogenicity of nuclei and ventricular system [38]. The method has no harmful side effects. Of particular interest is the mesencephalic scanning plane, including brainstem, substantia nigra and raphe nuclei. In terms of clinical implications, TCS can aid differential diagnosis (e.g. in movement disorders [90]) and has shown promise in predicting treatment response in psychiatric disorders in adult patients. As yet, no study has explored whether TCS can predict the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions. TCS is optional for the patients. As a well-tolerated investigation, it offers fast, non-invasive, targeted imaging in this age group in which magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not feasible or practical.

Furthermore, saliva samples are collected before step 1 (T0/T1) and after step 2 treatment (T3) to determine predictive genetic and epigenetic patterns. These saliva samples are collected according to standard protocol of the ESCAmark subproject, which coordinates biosampling across the ESCAlife consortium. Samples are stored at − 80 °C and will be analysed after recruitment closure of all RCTs within ESCAlife. Samples will be used according to the ethics vote and data management plan of ESCAmark that will be published separately.

Randomisation procedure

Central randomisation with a 1:1 treatment ratio, analogous to the other ESCA trials [37,38,39], is performed by the CTU at the University Medical Centre Freiburg via fax, using block randomisation with variable block length to ensure concealment of randomisation. Randomisation is stratified by centre. The randomisation request form contains the study-specific patient identification number, year of birth and the confirmation of ADHD above the cut-off. The CTU reviews the patient’s details on the randomisation fax and performs the randomisation if the data on the fax are appropriate and complete.

Quality assurance and monitoring

The monitoring is performed by the clinical research associates (CRAs) of the CTU. Adapted monitoring is accomplished according to Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP E6) and standard operating procedures (SOP). This verifies that patients’ rights and well-being are protected, that reported trial data are accurate, complete and verifiable from source documents, and that the trial is conducted in compliance with the currently approved protocol/amendment, with GCP and with the applicable regulatory requirements to ensure safety and integrity of clinical trial data. In this trial, all trial-specific monitoring procedures, monitoring visit frequency and the extent of source data verification (SDV) are predefined in a specific monitoring manual.

The investigator accepts monitoring visits before, during and after the clinical trial. Prior to the trial, a pre-trial telephone consultation and a site initiation visit at each site are conducted in order to train and introduce the investigators and their staff to the trial protocol, essential documents and related trial-specific procedures, ICH-GCP and national/local regulatory requirements.

During the trial, the monitor visits the site regularly depending on the recruitment rate and quality of data. During these on-site visits, the monitor verifies that the trial is being conducted according to the trial protocol, trial-specific procedures, ICH-GCP and national/local regulatory requirements. Moreover, the monitor checks that signed informed consent has been provided, and verifies the eligibility of patients, completeness of primary endpoint questionnaires, treatment compliance, and documentation. The monitor also performs source data verification to ensure that clinical trial data are recorded and documented in the source data and that case report forms (CRFs) are complete and accurate. In the case of data quality problems or a high number of protocol violations at individual sites, the extent of source data verification and frequency of monitor visits is adapted accordingly.

The investigator must maintain source documents for each patient in the trial, consisting of case and visit notes (hospital or clinic medical records) containing demographic and medical information, laboratory data, and the results of any other tests or assessments. All information recorded on CRFs must be traceable to source documents in the patient’s file. The investigator must also keep the original signed informed consent form (a signed copy is given to the patient).

The investigator must give the monitor access to all relevant source documents to confirm their consistency with the CRF entries.

An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), composed of Prof. Dr. H. J. Freyberger, Prof. Dr. A. Rothenberger and Prof. Dr. J. Schmitt, advises the trial sponsor on patient safety and measures to ensure the credibility and integrity of the ongoing trial.

Stopping rules

Inclusion in the study is not possible without written informed consent of parents/guardians. If a preschool child requires inpatient treatment or needs a different kind of treatment for health reasons according to the judgment of the attending physician, the child will be excluded from the study. Study exclusion will also occur if any other factors arise which affect the child’s well-being. The Ethics Committee will be informed immediately in the case of severe events during the conduct of the trial. Global stopping rules for the trial or closing of a centre include the emergence of data leading to a revision of the risk-benefit ratio, ongoing failure of recruitment, or repeated violations of standard GCP rules or of the study protocol. For a decision on the termination of the trial or on closing a participating centre, agreement between the study coordinator, PIs, site investigators, DMC members, the responsible Ethics Committee and the CTU Freiburg is intended.

Sample size and power calculations

The whole stepped care design is primarily powered for the two RCTs in step 1 and step 2. Based on the results of previous studies, an effect size of d = 0.5 is expected for the RCT in step 1 (TASH compared to a waitlist control group). Kierfeld et al. [30] found a moderate to large effect (d = 0.79) of a TASH intervention compared to a waitlist control group on parent-rated ADHD symptoms. Both the intervention and the outcome measure were similar to those used in this current trial. Effect sizes of about SMD = 0.75 were found for parent management training interventions, mainly compared to waiting groups in children with disruptive behaviour problems, using unblinded parent ratings [18]. However, reported effects sizes are smaller when blinded ratings are applied [23]. Therefore, we expect an effect size of d = 0.5 for the primary outcome for the randomisation comparing PMPTT with TAU in step 2.

The calculation of the sample size (software: STPLAN Version 4.3) is based on the primary endpoint of step 2 (ADHD/ODD change score from T2 to T3). Using a two-sided t test with a power of 80% at a significance level of 5%, 64 patients with non-missing data per group are required to detect a difference when the true effect size is d = 0.5. To account for the possibility that some patients (10%) will have incomplete data at T3, in total, 144 partial or non-responders should be randomised at step 2. We assume that about 20% (n = 36) will show a full response after step 1 [30] and that a group of 10% will have dropped out from T1 to T2. Therefore, 180/0.9 = 200 patients should be randomised at T1 (step 1). Given 180 patients with complete data and a presumed true effect size of d = 0.5, the power to detect a difference is 92%. We assume that about 300 patients will need to be screened for study participation.

Statistical analyses

Before the inclusion of the first patient, a detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) was prepared. This will be completed during the ‘blind review’ of the data, at the latest. If the SAP contains any changes to the analyses outlined in the trial protocol, they will be marked as such, and reasons for amendments will be given.

All statistical programming for analysis will be performed with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Definition of populations included in the analyses

The primary analysis will be conducted according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. This means that the patients will be analysed in the treatment arms to which they were randomised, irrespective of whether they refused or discontinued the treatment or whether other protocol violations become apparent.

The per-protocol (PP) population is a subset of the full analysis set (FAS) and is defined as the group of patients who had no major protocol violations, received a predefined minimum dose of the treatment and underwent the examinations required for the assessment of the endpoints at relevant, predefined times. The analysis of the PP population will be performed for the purpose of a sensitivity analysis.

Safety analyses will be performed in the safety population. Patients in the safety population are analysed as belonging to the treatment arm defined by treatment received. Patients are included in the respective treatment arm if treatment was started/if they received at least one dose of trial treatment.

Patient demographics/other baseline characteristics

Demographic and other baseline data (including disease characteristics) will be summarised descriptively using all documented patients. Continuous data will be summarised by arithmetic mean, standard deviation, minimum, 25% quantile, median, 75% quantile, maximum, and the number of complete and missing observations. If appropriate, continuous variables can also be presented in categories. Categorical data are summarised by the total number of patients in each category and the number of missing values. Relative frequencies are displayed as valid percentage (number of patients divided by the number of patients with non-missing values).

Analysis of primary endpoint

The primary statistical analyses of steps 1 and 2 will be by ITT, that is, all randomised patients will be analysed according to their allocated arm. Changes in the DCL ADHD + ODD (DBD) Parent scores between T1-baseline and T2 (after TASH/waiting) or T2 (after TASH) and T3, respectively, will be evaluated in separate mixed-effects models for repeated measures (MMRM). The MMRMs will include fixed categorical effects of treatment, centre, visit and treatment-by-visit interaction, and continuous, fixed covariates of baseline and baseline-by visit interaction. Further covariates predictive of missingness will be included based on a pre-specified selection strategy, to correct for potential bias arising from missing data.

Unstructured covariance matrices will be used to model within-patient correlations. The primary treatment comparisons of the change scores at T2 and T3 will be based on least-squares means with two-sided 95% confidence intervals without correction for multiple testing. Other possibly relevant covariates may be considered as well. Subgroup analyses will be conducted in an exploratory manner by including interaction terms in the MMRMs. These will focus on the analyses of patients’ and parents’ comorbidity. In addition, gender effects will be investigated as prognostic and predictive factors. Exploratory within-subjects comparisons (change in step 1 compared to change in step 2) will also be also carried out in MMRMs. Secondary efficacy endpoints derived from other scale scores will be analysed in the same manner, i.e. with the same type of linear model. Follow-up of full responders after step 1 will be evaluated descriptively. No interim analysis for efficacy will be performed.

Safety/tolerability analyses will be carried out in all patients for whom one of the randomised treatments was started, according to treatment received.

Analysis of secondary endpoints

Secondary endpoints will be analysed descriptively in a similar fashion to the primary outcome. Scores will be calculated according to the respective manuals.

The analysis of the change between T1-baseline and T2 (after TASH/waiting) and T3 (after TAU/PMPTT) comprises the analysis of the primary endpoint for continuous measurements (DCL-ADHS, DCL-SSV, FBB-ADHS, FBB- SSV, CU-Preschool, CBCL/1,5–5, CTRF, WFIRS, KIDDY KINDL, FZEV, FPNE, VER). In addition, for DCL-ADHS and the measurements listed above, change between T2 and T3 in patients without ADHD/ODD (at T2) will be evaluated. Treatment effects will be calculated with two-sided 95% confidence intervals.

The within-patient changes between T2 and T3 in patients without ADHD/ODD (at T2) in continuous endpoints will be analysed using linear regression adjusted for the baseline measurement and study centre.

The difference in the CGI between T1 and T2 and between T2 and T3 in the randomised steps will be analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The within-patient difference in the CGI will be analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Possible predictors of the DCL-ADHD score will be analysed using linear regression.

Legal and ethical foundation

Before trial start, all relevant documents were submitted to the local Ethics Committee responsible for the respective participating centres. The primary vote on the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Philipps University of Marburg. For changes to the trial protocol that are formal in nature or include relevant changes for participants, the ethics committees have to vote anew.

Discussion

ESCApreschool (investigating 3–6-year-old preschool children with ADHD) is one part of the multicentre study ESCAlife, which examines clinical care for children, adolescents and adults with ADHD to optimize evidence-based personalised stepped care approaches across different age groups (see also [37,38,39]).

Early onset, high prevalence and persistence, and developmental comorbidity make ADHD a psychosocially impairing and cost-intensive mental disorder. Despite continuous treatment research, there is still a substantial need to optimise individualised treatment strategies in order to improve outcomes and reduce the economic burden. By covering the full spectrum of ADHD at all ages, the consortium will be able to make significant recommendations for improving ADHD treatment in routine clinical care.

Clinical guidelines recommend an adaptive treatment and a stepped care approach for the treatment of ADHD/ODD [12]. However, this approach has not yet been empirically validated. The main goal of ESCApreschool is therefore to assess the efficacy of a stepped care approach in children with ADHD/ODD aged 3–6 years and to identify predictors as well as moderators of treatment outcome. The design combines two RCTs. The first aims to analyse the efficacy of the low-threshold TASH intervention by means of a randomised waiting control design and to identify predictors of response. Partial and non-responders to TASH take part in a second RCT, which compares the effects of an intense behaviour therapy addressing parents, children and preschool teachers with TAU. Thus, the design allows for the evaluation of the additional effects of behaviour therapy and TAU in preschool children with ADHD/ODD who did not sufficiently respond to the low-threshold intervention in step 1 of the study.

The results will improve future guidelines on the treatment of preschool-age children with ADHD and/or ODD. Moreover, the findings may also be used to develop usable, potentially more cost-effective, individualised stepped care pathways for young children with ADHD/ODD. The evaluation of predictors of treatment response will help to identify indications for specific treatments during the therapy process. Resource-intensive therapeutic interventions can then be specifically directed at individuals who will probably not respond to or benefit from low-threshold treatment. This would help to distribute resources efficiently and improve treatment for preschool psychiatric patients. Such a targeted, resource-friendly use of interventions will help children with ADHD, their families, preschool teachers, peers, the health care system and society as a whole.

Trial status

The trial was registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) as a Current Controlled Trial under DRKS00008971 on 1 October 2015. This manuscript is based on protocol version 3 (14 October 2016). Recruitment started January 2016 with the first patient enrolled on 29. June 2016 (first patient in). The milestone of 75% (150 patients) was reached in June 2019. Recruitment for this trial is ongoing. Recruitment will be completed in approximately December 2019.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- AKiP:

-

School of Child and Adolescent Cognitive Behaviour Therapy [Ausbildungsinstitut für Kinder- und Jugendlichenpsychotherapie]

- Booster SH:

-

Booster Self-Help

- CAP:

-

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- CBCL 1½-5:

-

Child Behaviour Checklist for Ages 1½-5

- CGI:

-

Clinical Global Impression Scale

- CRF:

-

Case report form

- C-TRF:

-

Caregiver and Teacher Report Form of the Child Behaviour Checklist

- CTU:

-

Clinical Trials Unit

- CUpreschool:

-

Parent Rating Callous-Unemotional Traits (preschool age)

- DASS:

-

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

- DBD:

-

Disruptive behaviour disorder

- DCL-ADHS:

-

Clinical ADHD Checklist [Diagnose-Checkliste für Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit−/Hyperaktivitätsstörungen]

- DCL-SCREEN:

-

Clinical Checklist for Screening Mental Disorders [Diagnose-Checkliste zum Screening psychischer Störungen]

- DCL-SSV:

-

[Diagnose-Checkliste für Störungen des Sozialverhaltens]

- DGKJP:

-

German Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie]

- DISYPS-III:

-

Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents Version III [Diagnostiksystem für psychische Störungen nach ICD10 und DSM-5 für Kinder und Jugendliche-III]

- DMC:

-

Data Monitoring Committee

- DRKS:

-

German Clinical Trials Register [Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien]

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Classification and Diagnostic Tool for Mental Disorders issued by the American Psychiatric Association

- ESCAadol:

-

Evidence-based stepped care of ADHD in Adolescents (aged 12–17 years)

- ESCAlate:

-

Evidence-based stepped care of ADHD in Adults (aged 16–45 years)

- ESCAlife:

-

Evidence-based stepped care of ADHD along the Lifespan

- ESCApreschool:

-

Evidence-based stepped care of ADHD in preschool children (aged 3–6 years)

- ESCAschool:

-

Evidence-based stepped care of ADHD in school children (aged 6–12 years)

- FAI:

-

Family Adversity Index

- FAS:

-

Full Analysis Set

- FBB-ADHS:

-

External Rating Questionnaire for ADHD [Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit/Hyperaktivitätsstörungen]

- FBB-SSV:

-

Self-Assessment Questionnaire for ADHD [Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Störungen des Sozialverhaltens]

- FPNE:

-

Questionnaire on Positive and Negative Parenting Behaviour [Fragebogen zum positiven und negativen Erziehungsverhalten]

- FZEV:

-

Questionnaire on Parenting Behaviour [Fragen zum Erziehungsverhalten]

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition

- ICH-GCP:

-

Good Clinical Practice

- ID:

-

Identifier

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- JTCI:

-

Junior Temperament and Character Inventory

- Kiddy-KINDL:

-

Instrument for assessing subjective generic health-related quality of life in preschoolers

- MMRM:

-

Mixed-effects model for repeated measures

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ODD:

-

Oppositional defiant disorder

- PEP:

-

Prevention Programme for Externalising Problem Behaviour [Präventionsprogramm für Expansives Problemverhalten]

- PI:

-

Principal Investigator

- PMPTT:

-

Parent Management and Preschool Teacher Training

- pp.:

-

per protocol

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SAP:

-

Statistical Analysis Plan

- SDQ :

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SDV:

-

Source Data Verification

- SMD:

-

Standardised Mean Difference

- SRS-short:

-

Social Responsiveness Scale, short version

- T0:

-

Screening at the beginning of the study (to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria)

- T0/T1:

-

Indicates overlap in diagnostic procedure of T0 and T1 assessment

- T1:

-

Assessment at baseline before step 1

- T2:

-

Assessment at the end of step 1 and before the beginning of the step 2 intervention

- T3:

-

Assessment at the end of the step 2 intervention

- T4:

-

Follow-up assessment 3 months after the end of the step 2 intervention

- TASH:

-

Telephone-Assisted Self-Help for parents and preschool teachers

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

- TCS:

-

Transcranial sonography

- THOP:

-

Treatment Programme for Children with Externalising Disorders [Therapieprogramm für Kinder mit hyperaktivem und oppositionellem Problemverhalten]

- VER:

-

Questionnaire assessing behaviour in risk situations [Verhalten in Risikosituationen]

- WFIRS:

-

Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale – Parent Report

- WPPSI-III:

-

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, third edition

References

Banaschewski T, Becker K, Döpfner M, Holtmann M, Rosler M, Romanos M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A current overview. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2017;114(9):149–59.

Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Döpfner M, Hollis C, et al. The quality of life of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):83–105.

Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

Huss M, Hölling H, Kurth BM, Schlack R. How often are German children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD? Prevalence based on the judgment of health care professionals: results of the German health and examination survey (KiGGS). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17:52–8.

Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):315–28.

Posner K, Melvin GA, Murray DW, Gugga SS, Fisher P, Skrobala A, et al. Clinical presentation of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in preschool children: The preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity treatment study (PATS). J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(5):547–62.

Hanisch C, Freund-Braier I, Hautmann C, Janen N, Pluck J, Brix G, et al. Detecting effects of the indicated prevention programme for externalizing problem behaviour (PEP) on child symptoms, parenting, and parental quality of life in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38(1):95–112.

Sonuga-Barke EJS, Koerting J, Smith E, McCann DC, Thompson M. Early detection and intervention for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(4):557–63.

Sonuga-Barke EJ, Halperin JM. Developmental phenotypes and causal pathways in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: potential targets for early intervention? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):368–89.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie (DGKJP). S3-Leitlinie zu ADHS im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenalter. URL: https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/028-045l_S3_ADHS_2018-06.pdf: AWMF online; 2017.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline). URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/resources/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-1837699732933; 2018.

Taylor E, Döpfner M, Sergeant J, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, et al. European clinical guidelines for hyperkinetic disorder - first upgrade. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13:7–30.

Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, McCracken J, Riddle M, Swanson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1284–93.

Mulqueen JM, Bartley CA, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: parental interventions for preschool ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(2):118–24.

Murray DW. Treatment of preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):374–81.

Charach A, Carson P, Fox S, Ali MU, Beckett J, Lim CG. Interventions for preschool children at high risk for ADHD: a comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1584–604.

Comer JS, Chow C, Chan PT, Cooper-Vince C, Wilson LA. Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: a meta-analytic examination. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(1):26–36.

Hautmann C, Hanisch C, Mayer I, Plück J, Döpfner M. Effectiveness of the prevention program for externalizing problem behaviour (PEP) in children with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder - generalization to the real world. J Neural Transm. 2008;115(2):363–70.

Plück J, Eichelberger I, Hautmann C, Hanisch C, Jaenen N, Döpfner M. Effectiveness of a teacher-based indicated prevention program for preschool children with externalizing problem behavior. Prev Sci. 2015;16(2):233–41.

Hautmann C, Hoijtink H, Eichelberger I, Hanisch C, Pluck J, Walter D, et al. One-year follow-up of a parent management training for children with externalizing behaviour problems in the real world. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(4):379–96.

Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, Daley D, Ferrin M, Holtmann M, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):275–89.

Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):21–37.

Klasen F, Meyrose AK, Otto C, Reiß F, Ravens-Sieberer U. Psychische Auffälligkeiten von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2017;165(5):402–7.

Franke N, Keown LJ, Sanders MR. An RCT of an online parenting program for parents of preschool-aged children with ADHD symptoms. J Atten Disord. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716667598.

Kierfeld F, Döpfner M. Bibliotherapy as a self-help program for parents of children with externalizing problem behavior. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2006;34(5):377–85.

O'Brien M, Daley D. Self-help parenting interventions for childhood behaviour disorders: a review of the evidence. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(5):623–37.

Tarver J, Daley D, Lockwood J, Sayal K. Are self-directed parenting interventions sufficient for externalising behaviour problems in childhood? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(12):1123–37.

Kierfeld F, Ise E, Hanisch C, Görtz-Dorten A, Döpfner M. Effectiveness of telephone-assisted parent-administered behavioural family intervention for preschool children with externalizing problem behaviour: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(9):553–65.

Ise E, Kierfeld F, Döpfner M. One-year follow-up of guided self-help for parents of preschool children with externalizing behavior. J Prim Prev. 2015;36(1):33–40.

Mokros L, Benien N, Mutsch A, Kinnen C, Schurmann S, Metternich-Kaizman TW, et al. Guided self-help interventions for parents of children with ADHD--concept, referral and effectiveness in a nationwide trial. An observational study. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2015;43(4):275–86.

Dose C, Hautmann C, Buerger M, Schürmann S, Woitecki K, Döpfner M. Telephone-assisted self-help for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who have residual functional impairment despite methylphenidate treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(6):682–90.

Hautmann C, Dose C, Duda-Kirchhof K, Greimel L, Hellmich M, Imort S, et al. Behavioral versus nonbehavioral guided self-help for parents of children with externalizing disorders in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2018;49(6):951–65.

Döpfner M, Breuer D, Schurmann S, Metternich TW, Rademacher C, Lehmkuhl G. Effectiveness of an adaptive multimodal treatment in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder -- global outcome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13(Suppl 1):I117–29.

Döpfner M, Ise E, Wolff Metternich-Kaizman T, Schurmann S, Rademacher C, Breuer D. Adaptive multimodal treatment for children with attention-deficit−/hyperactivity disorder: an 18 month follow-up. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46(1):44–56.

Döpfner M, Hautmann C, Dose C, Banaschewski T, Becker K, Brandeis D, et al. ESCAschool study: trial protocol of an adaptive treatment approach for school-age children with ADHD including two randomised trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):269.

Geissler J, Jans T, Banaschewski T, Becker K, Renner T, Brandeis D, et al. Individualised short-term therapy for adolescents impaired by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder despite previous routine care treatment (ESCAadol)-Study protocol of a randomised controlled trial within the consortium ESCAlife. Trials. 2018;19:254.

Zinnow T, Banaschewski T, Fallgatter AJ, Jenkner C, Philipp-Wiegmann F, Philipsen A, et al. ESCAlate - Adaptive treatment approach for adolescents and adults with ADHD: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:280.

Döpfner M, Plück J, Dose C, Eichelberger I, Schürmann S, Wolf M-KT. ADHS-Coaching für ErzieherInnen (3–6): Ein Selbsthilfeprogramm für ErzieherInnen von Vorschulkindern mit ADHS-Problemen im Alter von 3 bis 6 Jahren. Köln: Klinik für Psychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie des Kindes- und Jugendalters an der Uniklinik Köln; 2015.

Döpfner M, Wolff Metternich-Kaizman T, Dose C, Katzmann J, Mokros L, Scholz K, et al. ADHS-Coaching für Eltern (3–6): Ein Selbsthilfeprogramm für Eltern von Vorschulkindern mit ADHS-Problemen im Alter von 3 bis 6 Jahren. Köln: Klinik für Psychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie des Kindes- und Jugendalters an der Uniklinik Köln; 2015.

Döpfner M, Schürmann S, Frölich J. Therapieprogramm für Kinder mit hyperkinetischem und oppositionellem Problemverhalten (THOP). 5th ed. Weinheim: Beltz; 2013.

Döpfner M, Schürmann S, Lehmkuhl G. Wackelpeter und Trotzkopf: Hilfen bei hyperkinetischem und oppositionellem Verhalten. Weinheim: Beltz; 2011.

Plück J, Wieczorrek E, Wolff Metternich T, Döpfner M. Präventionsprogramm für Expansives Problemverhalten (PEP): Ein Manual für Eltern und Erziehergruppen. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2006.

Braun S. Entwicklung und Evaluation des Therapieprogramms zur Steigerung von Organisationsfähigkeit, Konzentration und Impulskontrolle bei Kindern mit ADHS. Universität Köln: THOKI-ADHS; 2018.

Döpfner M, Görtz-Dorten A. DISYPS-III : Diagnostik-System für Psychische Störungen nach ICD-10 und DSM-5 für Kinder und Jugendliche - III. Bern: Hogrefe; 2017.

Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmology. USA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1976.

Lange M, Kamtsiuris P, Lange C, Schaffrath Rosario A, Stolzenberg H, Lampert T. Messung soziodemographischer Merkmale im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) und ihre Bedeutung am Beispiel der Einschatzung des allgemeinen Gesundheitszustands. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50(5–6):578–89.

Petermann F, Wechsler D. Wechsler nonverbal scale of ability: [WNV]; Manual zur Durchführung und Auswertung; Übersetzung und Adaptation der WNV von David Wechsler. Frankfurt/M: Pearson; 2014.

Döpfner M, Plück J, Claudia K. Deutsche Schulalter-Formen der Child Behavior Checklist von Thomas M. Achenbach: CBCL 6-18R, TRF 6-18R, YSR 11-18R, Elternfragebogen über das Verhalten von Kindern u. Jugendlichen (CBCL/6-18R), Lehrerfragebogen über das Verhalten von Kindern u. Jugendlichen (TRF/6-18R), Fragebogen für Jugendliche (YRS/11-18R). Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2014.

Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Do callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(12):1308–15.

Weiss MD, Brooks BL, Iverson GL, Lee B, Dickson RA, Wasdell M. Reliability and validity of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale. In: Boston, 54th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (abstract); 2007.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(5):399–407.

Strayhorn JM, Weidman CS. A Parent Practices Scale and its relation to parent and child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(5):613–8.

Imort S, Hautmann C, Greimel L, Katzmann J, Pinior J, Scholz K, et al. Der Fragebogen zum positiven und negativen Erziehungsverhalten (FPNE): Eine psychometrische Zwischenanalyse. Poster zum 32. In: Symposium der Fachgruppe Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie der DGPs, Braunschweig; 2014.

Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The triple P-positive parenting program: a comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(4):624–40.

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995.