Abstract

Background

Investigator-initiated clinical studies (IITs) are crucial to generate reliable evidence that answers questions of day-to-day clinical practice. Many challenges make IITs a complex endeavour, for example, IITs often need to be multinational in order to recruit a sufficient number of patients. Recent studies highlighted that well-trained study personnel are a major factor to conduct such complex IITs successfully. As of today, however, no overview of the European training activities, requirements and career options for clinical study personnel exists.

Methods

To fill this knowledge gap, a survey was performed in all 11 member and observer countries of the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN), using a standardised questionnaire. Three rounds of data collection were performed to maximize completeness and comparability of the received answers. The survey aimed to describe the landscape of academic training opportunities, to facilitate the exchange of expertise and experience among countries and to identify new fields of action.

Results

The survey found that training for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and investigator training is offered in all but one country. A specific training for study nurses or study coordinators is also either provided or planned in ten out of eleven countries. A majority of countries train in monitoring and clinical pharmacovigilance and offer specific training for principal investigators but only few countries also train operators of clinical research organisations (CRO) or provide training for methodology and quality management systems (QMS). Minimal requirements for study-specific functions cover GCP in ten countries. Only three countries issued no requirements or recommendations regarding the continuous training of study personnel. Yet, only four countries developed a national strategy for training in clinical research and the career options for clinical researchers are still limited in the majority of countries.

Conclusions

There is a substantial and impressive investment in training and education of clinical research in the individual ECRIN countries. But so far, a systematic approach for (top-down) strategic and overarching considerations and cross-network exchange is missing. Exchange of available curricula and sets of core competencies between countries could be a starting point for improving the situation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Investigator-initiated clinical studies (IITs) help to answer questions that clinicians face in their day-to-day practice. They are initiated and managed in a non-commercial setting by a researcher/s (individual investigator, academic institution, a collaborative study group, etc). IITs play a vital role in the generation of evidence that can eventually drive policy. A good IIT is one that asks a question that has scientific merit, has robust research methodology, has rigorous ethical and scientific governance, a committed and motivated investigator, institutional support, a funding agency that recognizes the value of the research and a team that backs him/her up [1]. However, there are many challenges posed by an IIT, as has recently been shown with the example of Portugal. Besides limited funds and missing local infrastructure, a lack of trained study personnel is seen as a major hurdle [2, 3]. More and more, IITs need to be multinational (e.g. in order to recruit sufficient numbers of patients), which increases their complexity.

Many important publications have emphasised and confirmed the importance of training and education to improve the quality, impact and efficiency of clinical research in general. The Lancet series on “Research: increasing value, reducing waste” [4,5,6,7,8] mentions that training and education are important measures for increased impact of clinical research results on medical therapies. The OECD says that support for and facilitation of the education, training and infrastructure required for academic clinical trials are key elements of the success of clinical research [9]. Qualified and experienced staff are essential at several levels for conducting clinical trials, as the German Scientific Council states [10].

But what does the European landscape for training in clinical research look like? The National Scientific Partners of the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN) are a major provider of training in clinical research and well informed on activities in their own countries. Therefore, a survey in ECRIN member and observer countries was performed to map the status of training activities at the national level in the National Scientific Networks. However, considerable heterogeneity between the partners with respect to involvement in national training activities has been reported. ECRIN is a sustainable, non-profit, distributed infrastructure with the legal status of a European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC). The vision of ECRIN is to generate scientific evidence with a focus on IITs to optimise medical standards of care. To this end, ECRIN supports investigators and (mainly) academic sponsors in the planning and design of multinational clinical research [11]. ECRIN has nine member countries and two observer countries (Table 1).

Scientific partners of ECRIN are national clinical research networks that are composed of academic clinical research centres (CRCs) or clinical trial units (CTUs) with a national coordinating centre (Table 1) [12]. As per ECRIN-ERIC statutes, the scientific partners must have developed shared tools, procedures and practices to facilitate multi-centre studies, have reached a critical mass in competence and represent the standard in the country [13].

Objectives of the survey:

-

To describe the landscape of academic training opportunities in clinical research as described by the ECRIN partners

-

To enable synergies by facilitating the exchange of expertise and experience in national training in clinical research

-

To identify new fields of action for ECRIN to increase the quality and efficiency of multinational clinical research

In Additional file 1 a longer description of ECRIN is included.

Methods

The survey was initiated in April 2018. A first version of the questionnaire was sent to the ECRIN members on 20 April 2018. The answers were compiled and presented at the NC meeting on 14 May 2018. It was decided to provide a first internal report and to give the individual countries the opportunity to go back to the questions and complete/update if needed.

As a consequence, the interim report and an updated questionnaire with a more standardised answer format were distributed to the members of the NC on 15 June 2018 with a deadline of 13 July 2018. On 14 August 2018, a reminder was sent to countries which had not yet provided the filled-in questionnaire. On 4 October 2018 the second round of data collection was completed and the next version of the report was finalised on 19 October 2018. The information provided was considered being of high value, but still too heterogenous to be shared with a broader audience. Therefore, the NC agreed to perform a third revision of the report, which was completed in January 2019.

Results

Overview

All members/observers from ECRIN participated in the survey. Table 2 gives an overview of the answers received.

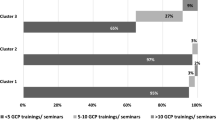

GCP training

Specific (basic and advanced) GCP training is provided by ECRIN members/observers in all but one country. The training is usually targeted at investigators, study nurses/coordinators and members of the research team and normally provided by the local CTU. In Germany it is provided as an introductory or refresher course. Standardised curricula are applied in Czech Republic (network standard), Hungary (accredited course, covered partly by the Hungarian Society of Pharmacology, with exams, which is valid for 5 years), Portugal (CLIC PharmaTrain [14]/ECRIN [15]), Slovakia and Switzerland (accredited by swissethics). In Ireland GCP training is targeted at IMP and medical devices (mandatory). GCP courses for investigators are mandatory in Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Portugal and Switzerland and are not mandatory in France and Spain, though GCP must be well known.

In some countries, there is a collaboration with commercial clinical research organisations (CROs) for GCP training (e.g. Norway, Portugal), some of them with Transcelerate recognition [16].

Study nurse/coordinator training

Specific study nurse, respectively coordinator training is provided or planned in ten countries (in preparation in Slovakia and Norway). In Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Spain and Ireland this training is optional; in Italy it is mandatory. The training is provided by CTUs (Germany, Ireland and Portugal), private companies (Italy and Portugal) or a mixed consortia (Hungary). Only in Germany is a standardised curriculum applied. Norway and Switzerland are in the planning phase for a curriculum.

Investigator training

Ten countries offer investigator training. Mandatory investigator courses are performed by local CTUs in Germany, Ireland and Switzerland and by a consortium in Hungary. A standardised curriculum has been implemented in Germany by KKSN and Portugal (CLIC level 1 plus level 2 for principal investigators (PIs) [14]). In Czech Republic, the training is optional.

Monitoring training

Monitoring training based upon a standardised curriculum is used in Czech Republic (mandatory for CZECRIN CRAs, provided by CZECRIN or an external agency) and Germany (optional, provided by CTUs). Monitoring training is also offered in France, Hungary, Norway, Portugal (by PTCRIN CTUs or external organizations), Spain and Switzerland (eight countries in total).

Pharmacovigilance training/training in clinical pharmacology

Training in clinical pharmacology is implemented in Germany, Hungary, Portugal and Spain. In Hungary it is intended for PIs and mandatory for phase 1 trials and optional for phase 2–3 trials. It is based upon standardised curricula and allows certification. The MD degree in clinical pharmacology should be regularly enforced with exams every 5 years. In CZECRIN, mandatory pharmacovigilance (PV) courses are provided by an external agency for CZECRIN staff based upon a standardised curriculum. Norway has had a medical speciality of clinical pharmacology taking 5 years since 1989. Portugal has a medical specialization with 4 years of training. Slovakia is planning a PV course for investigators and study nurses. In Switzerland, a MD can acquire a recognised specialty title in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, duration 5 years.

PI/coordinator training

Seven countries perform PI/ coordinator training. The PI training offered in Germany and Portugal is optional, based on a standardised curriculum by KKSN or PTCRIN/UNAVE (Aveiro University [14]) and provided by the CTUs (Germany) or by e-learning platform (Portugal). In addition, there is optional and non-standardised training for study coordinators. In Switzerland, mandatory PI/sponsor-investigator training is available.

Training of CRO operators (staff operating or working for a CRO)

Italy has comprehensive, mandatory training for CRO operators for all activities, including monitoring, quality, GCP, good manufacturing practice (GMP) and PV (mainly for phase I trials). Germany and Portugal offer training for CRO operators as well.

Methodological training

In Ireland, a wide range of training in trial methodology based upon national curricula is provided and performed nationally through HRB TMRN. Also, Spain, Portugal (CLIC level 2 [14] and others) and Switzerland offer such training. France has a specific methodological training in Parkinson’s disease. In a collaboration between Harvard Medical School and the Portuguese government, Portugal has implemented a clinical scholars research training programme dedicated to medical doctors [17].

Quality management system training

Quality management system (QMS) training is provided in Czech Republic, France (optional), Portugal (optional), Germany and Ireland (mandatory and provided nationally through HRB-CRCI).

Postgraduate training

There are several activities with respect to postgraduate training. In Czech Republic, a mandatory clinical trials course for PhD students, using a standardised PhD curriculum, is provided by local CZECRIN staff and senior clinical researchers. Germany has a broad spectrum of master programmes, including a Master of Clinical Trial Management (MSc), a “Clinical Evaluation” study programme, a master of science in “Clinical Research & Translational Medicine”, a master of science in “Medical Biometry/Biostatistics” and a master of science in “Pharmaceutical Medicine”. Ireland [18,19,20,21,22] and Switzerland [23] also provide different optional postgraduate training courses in clinical research (MSc courses and other postgraduate courses, including a specialty title in Pharmaceutical Medicine for MDs and dedicated PhD programmes for clinical researchers). Portugal has implemented a master in clinical research management (MEGIC) [24] and has several PhD and master courses on epidemiology and clinical research. The latter is offered in Norway as well. Postgraduate courses in Hungary and Slovakia were not further specified. Table 3 provides complementary information.

Other types of training, general remarks

France offers MD training courses focused on good practice and technical issues (optional). Ireland offers two optional training programmes aimed at medical device development, training and education. In Germany, an advanced training course for clinical studies with medical devices is offered (complementary to the investigator training and following a standardised curriculum).

Other specific training activities were reported from several countries. Germany offers training courses in medical English for study personnel as well as for people handling dangerous goods. Hungary offers project-specific training, HRDOP [34], ERASMUS [35]. France offers a broad range of specific training courses in e.g. imaging, European trials, study drug issues, basic information for patients (responsible representatives), risk management, rare diseases, human sample collection, and data management [36]. Furthermore, a “train the trainer” program is offered for clinical research [37].

In Spain, besides GCP and methodology, all training is internal for SCReN members (and mandatory). In Switzerland, a comprehensive list showing all clinical research training provided by the network is available (see also [23]).

Minimal requirements for a study specific function (e.g. CRA, biostatistician)

Minimal requirements for study-specific functions cover GCP in ten countries: Czech Republic (PI, study team members), France, Germany (study personnel), Hungary, Ireland (clinical research staff), Norway (PI), Portugal (clinical research staff), Slovakia (investigators), Spain (PI) and Switzerland. Additional requirements have been reported for phase I units in France and Hungary [38], for CRO operators in Italy and for PIs and sponsor PIs in Switzerland.

National requirements for continuous education in clinical research

Eight countries have national requirements for continuous training. Repeated GCP training is required in Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland and Spain (commonly every 2 years), in Portugal (every 3 years), Hungary (every 5 years) and Slovakia. Swissethics recommends that after the initial Training in Research Ethics and GCP has taken place, the knowledge is maintained by regular research activity, e.g. conducting clinical trials, attending continuing education related to research or GCP refresher courses, being exposed to GCP inspections, etc. In Hungary, participation in yearly educational programmes is highly advised and in an ongoing project the qualification requirements and the duration of their validity will be determined for the clinical trial team in human clinical studies. In Germany, refresher courses every 2 years for medical devices are mandatory. In Spain, in phase 1 trial units, certification for cardiovascular resuscitation and emergency treatment is required. No national requirements were reported from France, Italy and Norway.

Overarching national strategy/roadmap/standards for training in clinical research

In four countries, an overarching national strategy is in place or foreseen for training: Germany (GCP training for investigators and study personnel according to the curriculum of the Federal Association of Physicians and ethics committees), Hungary (Committee on Clinical Pharmacology and Medical ethics of the Medical Research School), Ireland (Health Research Board strategy for development of the national network and funding of HRB-CRCI and HRB Trials Methodology Research Network (TMRN)) and Switzerland (Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) 2016–20,121 roadmap for building up the future generation of clinical researchers encompasses a total of five work packages, the SCTO contributes to the implementation [39]). In Hungary, the training materials (curriculum, admission and exclusion criteria) resulting from the HRDOP project will be presented to the Medical Research Council (ETT) and the National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition (OGYÉI) as well. No national strategy has been specified for France, Italy, Norway, Portugal and Slovakia. In Czech Republic, a national strategy is prepared within the Working Committee for Clinical Trials at the Ministry of Health and for Spain no information is available.

Career options for clinical research per country

In Table 3 career options and academic titles for clinical research are listed per country.

Career options for clinical research are still limited in the majority of countries. The same is true for academic titles, respectively degrees specific for clinical research; however, new options for masters and diplomas have been created.

Necessity for complementary international training in clinical research

All countries participating in the survey support the idea of offering international training in clinical research. Concrete proposals were made by Czech Republic (MSc programmes in “Pharmaceutical Medicine”), France (master degree for PIs of multinational studies), Germany (specific management related to international research projects, e.g. PharmaTrain, where Hungary organised two courses in pharmaceutical development), Portugal (CLIC III for sponsor-coordinators and face to face courses focusing on key topics, e.g. protocol design, H2020), Spain (international regulatory requirement training, international clinical trials coordination, VHP and new centralised evaluation of clinical trials under the new regulation (536/2014) and Switzerland (training for “lead” CTUs to facilitate multinational trials). E-learning courses would be of interest for Czech Republic and France. A coordination role of ECRIN in this area is proposed by Germany, Hungary, Ireland and Norway. Certification would be an option for Ireland and Italy (if certification is recognised at the national level). Slovakia has no suggestions yet.

Discussion

The European countries included all have academic training opportunities in clinical research, but to different extents. The respondents are open to foster the exchange of expertise and experience in national training in clinical research as well as for a more active role of ECRIN to identify new fields of action, increasing the quality and efficiency of multinational clinical research.

The investment of the national and local networks in training and education is substantial and impressive. But so far, building up training and education programmes is rather a bottom-up process serving current needs. Furthermore, there are few systematic approaches for (top-down) strategic and overarching considerations, active promotion and cross-network exchange. However, the EU just recently funded an ERASMUS+ project (CONSCIOUS: Curriculum Development of Human Clinical Trials for the Next Generation Biomedical Students). This consortium is led by Hungary in collaboration with France, Ireland, Czech Republic and Portugal and is intended to tackle skill gaps and mismatches related to European-level clinical trial professionals [23].

More exchange between National Scientific Networks of ECRIN member and observer countries may inspire their national plans, projects and negotiations. The information may furthermore serve as a benchmark to position, scrutinise and further develop their own organisation. The national view may be challenged and enriched by the broader European picture. And last but not least, access to information, documents and expertise should lead to a mutual benefit for all members, avoiding duplication of efforts and a waste of taxpayer money. Showing and promoting the impact and (untapped) potential of a network of networks may help to support the continuation of national funding. ECRIN and the scientific partners may also support the European Union (respectively the responsible taskforces) in continuously harmonising training once the Clinical Trial Regulation (EU number 536/2014) enters into force.

Curricula for clinical research functions/determination of core competencies for specific functions (e.g. for universal functions like (principal) investigator or study nurse) and a European-wide agreement on curricula and core competencies could be an aim. As a starting point, the exchange of available curricula and sets of core competencies could improve professionalism.

Training offered by ECRIN should be distinguished between “internal training” (for the CTUs and networks) and “external training” (e.g. for clients like investigators). Whereas the latter may preferably be offered at the national or even local level (may be supported by central offers for multinational, European or international aspects), internal training at the European level could be of high value.

The national networks are increasingly creating and offering jobs for highly qualified staff. Furthermore, academic career paths are starting to be offered more systematically and are officially recognised, resulting in titles (e.g. PhD in clinical research). This will lead to more professionalism in clinical research and will attract more young talents. ECRIN may map and monitor this development and facilitate staff exchanges between national networks.

There are some limitations of the survey. Data collection has been restricted to 11 member and observer countries of ECRIN and the coordinating units of the National Scientific Networks. The ECRIN partners served as a convenient and representative sample. However, we cannot exclude other training initiatives not known to the network. As a consequence, the information may not be complete in all cases and may not be representative for the European Union. In addition, heterogeneity in the use of clinical research terms was identified in the survey. As an example, different countries have a different understanding of the profile of a study coordinator. For some countries this means “coordinating investigator”, for others it means rather a project manager function or is a synonym for study nurse. Defining the different profiles in advance may help to get a more consistent result in the future. The same is true for academic titles and degrees (PhD, master, etc.) versus career options (CRA, data manager, etc.). Nevertheless, the survey has been performed in three rounds with stepwise improvement of the information and face to face discussions between the survey participants and thus gives a good overview of the training activities in the participating countries (see Additional file 2).

Conclusions

There is a substantial and impressive investment in training and education of clinical research in the individual ECRIN countries. But so far, a systematic approach for (top-down) strategic and overarching considerations and cross-network exchange is missing. Exchange of available curricula and sets of core competencies between countries could be a starting point for improving the situation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CLIC:

-

Clinical investigator certificate

- CR:

-

Clinical research

- CRA:

-

Clinical research associate

- CRC:

-

Clinical research centre

- CRO:

-

Clinical research organisation

- CT:

-

Clinical trial

- CTA:

-

Clinical trial application

- CTU:

-

Clinical trial unit

- DM:

-

Data management

- ECRIN:

-

European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network

- ERASMUS:

-

EuRopean Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students

- ERIC:

-

European Research Infrastructure Consortium

- GCP:

-

Good Clinical Practice

- GDPR:

-

General Data Protection Rule

- GMP:

-

Good Manufacturing Practice

- H2020:

-

Horizon 2020

- ICN:

-

International Clinical Trial Network

- IIT:

-

Investigator-initiated trial (or study)

- IMP:

-

Investigational medicinal product

- MD:

-

Medical doctor

- MSc:

-

Master of science

- NC:

-

Network committee

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PhD:

-

Doctor of philosophy

- PI:

-

Principal investigator

- PV:

-

Pharmacovigilance

- QA:

-

Quality assurance

- QM:

-

Quality management

- QMS:

-

Quality management system

- SAS:

-

Self-assessment sheet

- SOP:

-

Standard operating procedure

- WG:

-

Working group

References

Konwar M, Bose D, Gogtay NJ, Thatte UM. Investigator-initiated studies: Challenges and solutions. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9:179–83. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_106_18.

Madeira C, Santos F, Kubiak C, Demotes J, Monteiro EC. Transparency and accuracy in funding investigator-initiated clinical trials: a systematic search in clinical trials databases. BMJ Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-02339.

Madeira C, Pais A, Kubiak C, Demotes J, Monteiro EC. Investigator-initiated clinical trials conducted by the Portuguese Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (PtCRIN). Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2016;4:141–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2016.08.002.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383:156–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1.

Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:166–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8.

Salman RA-S, Beller E, Kagan J, Hemminki E, Phillips RS, Savulescu J, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet. 2014;383:176–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62297-7.

Chan A-W, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet. 2014;383:257–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62296-5.

Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383:267–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Facilitating international co-operation in non-commercial clinical trials. 2011. http://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/49344626.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

Wissenschaftsrat. Empfehlungen zu klinischen Studien. 2018. https://www.wissenschaftsrat.de/download/archiv/7301-18.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN). Who we are. 2019. https://ecrin.org/who-we-are. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN). Members & observers. 2019. https://ecrin.org/who-we-are/members-observers. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN). Statutes. 2013. https://www.ecrin.org/sites/default/files/ECRIN%20statutes/Statutes%20ECRIN%20EN.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2019.

Association for Drug Discovery and Development. Clinical Investigator Certificate. 2018. http://clic.pharmaceutical-medicine.pt/. Accessed 23 Apr 2019.

Boeynaems J-M, Canivet C, Chan A, Clarke MJ, Cornu C, Daemen E, et al. A European approach to clinical investigator training. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00112.

TransCelerate BioPharma Inc. Our work in clinical development. 2017. https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/what-we-do/work-clinical-development/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Harvard Medical School. Office for External Education. Portugal clinical scholars research training. 2019. https://postgraduateeducation.hms.harvard.edu/certificate-programs/custom-programs/portugal-clinical-scholars-research-training. Accessed 23 Apr 2019.

National University of Ireland Galway. MSc (Clinical Reserach) – Full-Time or Part-Time. 2018. http://www.nuigalway.ie/taught-postgraduate-courses/clinical-research.html. Accessed 15 Sep 2018.

University College Dublin School of Medicine. MSc Clinical & Translational Research - Full Time. 2012. http://www.ucd.ie/medicine/studywithus/graduatestudies/clinicalresearch/mscclinicaltranslationalresearch-fulltime/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

University College Dublin School of Medicine. Graduate Certificate in Clinical Research. 2012. http://www.ucd.ie/medicine/studywithus/graduatestudies/clinicalresearch/graduatecertificateinclinicalresearch/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

University College Cork. UCC Postgraduate Courses. 2019. https://www.ucc.ie/en/study/postgrad/taughtcourses/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Clinical Research Development Ireland. The Wellcome - HRB Irish Clinical Academic Training (ICAT) Programme. 2017. https://www.crdi.ie/research/wellcome-hrb-icat-programme/. Accessed 27 Mar 2019.

Swiss Clinical Trial Organisation. Training Opportunities. 2019. https://www.scto.ch/en/education-and-careers/training.html. Accessed 26.030.2019.

Universidade Nova De Lisboa. Nova Medical School. Master in Clinical Research Management - MEGIC. http://www.nms.unl.pt/main/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2346:master-in-clinical-research-management-megic&catid=2:uncategorised&Itemid=482&lang=pt. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Universität Leipzig Medizinische Fakultät. M.Sc. Clinical Research & Translational Medicine. https://www.zks.uni-leipzig.de/Masterstudium-Clinical-Research. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Universität Duisburg-Essen Akademisches Beratungszentrum. Pharmaceutical Medicine (M.Sc.). 2019. https://www.uni-due.de/studienangebote/studiengang.php?id=82. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg Medizinische Biometrie und Informatik. Msc Medical Biometry. 2019. https://www.klinikum.uni-heidelberg.de/Profil.100261.0.html. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

Dresden International University. Clinical Research (MSc). 2019. https://www.di-uni.de/studium-weiterbildung/medizin/clinical-research. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Centrial Kooperationspartner des Universtiätsklinikum Tübingen. Fortbildungen. 2015. https://www.centrial.de/fortbildungen/fortbildungsuebersicht/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

IUBH Internationale Hochschule Fernstudium. MBA Clinical Research Management. 2019. https://www.iubh-fernstudium.de/master/masterstudiengaenge/gesundheit-und-soziales/mba-clinical-research-management/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

MSB Medical School Berlin Hochschule für Gesundheit und Medizin. Studium Medical Research and Management (Bachelor of Science). https://www.medicalschool-berlin.de/studiengaenge/fakultaet-gesundheitswissenschaften-fachhochschule/bachelorstudiengaenge/medical-research-and-management. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Beuth Hochschule für Technik in Berlin. Clinical trial management. 2018. http://www.beuth-hochschule.de/ctm/. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

European Centre of Pharmaceutical Medicine University of Basel. Postgraduate degrees. http://web.ecpm.ch/degrees/. Accessed 2 Apr 2019.

Miniszterelnökség. Human Resource Development Operational Programme. 2016. https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/human_resource_development_operational_programme. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

European Commission. Erasmus +. Curriculum development of human clinical trials for the next generation of biomedical students. 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018-1-HU01-KA203-047811. Accessed 23 Apr 2019.

French Clinical Research Infrastructures Network (FCRIN). Training course advisor. 2015. https://www.fcrin.org/training-course-advisor/informations-referencees/les-formations. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Université Paris Diderot Faculte de Medicine. Formation qualifiante de perfectionnement pédagogique pour les formateurs à l’investigation clinique. 2014. https://www.fcrin.org/sites/default/files/formation_programme/fpp_edition-2_plaquette.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Semmelweis University. The Clinical Pharmacology is a prerequisitefor acquiring a specialized qualification (org. A Klinikai Farmakológia ráépített szakképesítés megszerzésének feltételei). 2014. http://semmelweis.hu/pharmacology/a-klinikai-farmakologia-raepitett-szakkepesites-megszerzesenek-feltetelei/. Accessed 15 Mar 2019.

Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Roadmap 2016–2021 for developing the next generation of clinical researchers. 2016. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/medizin-und-forschung/biomedizinische-forschung-und-technologie/masterplan-zur-staerkung-der-biomedizinischen-forschung-und-technologie/roadmap-nachwuchsfoerderung-klinische-forschung.html. Accessed 26 Mar 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the ECRIN-ERIC Network Committee members as well as other staff of the ECRIN Scientific Partners for their contributions to the survey and feedback on the report and publication. Thanks to Michaela Egli (Swiss Clinical Trial Organisation) for helping with the manuscript.

Funding

This survey was conducted with no external funding or specific internal funding. Work was done within the usual employment contract.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM and CO prepared the survey, performed it, did the analysis and provided several draft versions as well as the final manuscript. VCI, GC, BČ, OD, RD, GB, FK, GLK, CLM, ECM, LP, DP, AP, OR, CS, FT and HL collected the data in the ECRIN member/observer countries and reviewed draft versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not necessary because it is a survey of existing training activities related to clinical research in individual countries used for assessment and improvement.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was given by the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Background information about ECRIN. Short overview on support areas, organisation and history of ECRIN. (PDF 233 kb)

Additional file 2:

Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Magnin, A., Iversen, V.C., Calvo, G. et al. European survey on national training activities in clinical research. Trials 20, 616 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3702-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3702-z