Abstract

Background

Although negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is widely used in the management of several wound types, its efficacy as a primary therapy for acute burns has not yet been adequately investigated, with research in the paediatric population particularly lacking. There is limited evidence, however, that NPWT might benefit children with burns, amongst whom scar formation, wound progression and pain continue to present major management challenges. The purpose of this trial is to determine whether NPWT in conjunction with standard therapy accelerates healing, reduces wound progression and decreases pain more effectively than standard treatment alone.

Methods/design

A total of 104 children will be recruited for this trial. To be eligible, candidates must be under 17 years of age and present to the participating children’s hospital within 7 days of their injury with a thermal burn covering <5% of their total body surface area. Facial and trivial burns will be excluded. Following a randomised controlled parallel design, participants will be allocated to either an active control or intervention group. The former will receive standard therapy consisting of Acticoat™ and Mepitel™. The intervention arm will be treated with silver-impregnated dressings in addition to NPWT via the RENASYS TOUCH™ vacuum pump. Participants’ dressings will be changed every 3 to 5 days until their wounds are fully re-epithelialised. Time to re-epithelialisation will be studied as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes will include pain, pruritus, wound progression, health-care-resource use (and costs), ease of management, treatment satisfaction and adverse events. Wound fluid collected during NPWT will also be analysed to generate a proteomic profile of the burn microenvironment.

Discussion

The study will be the first randomised controlled trial to explore the clinical effects of NPWT on paediatric burns, with the aim of determining whether the therapy warrants implementation as an adjunct to standard burns management.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12618000256279. Registered on 16 February 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The acute burn wound is a complex, dynamic injury that presents a range of challenges for patients and clinicians alike. It has been described as “the ultimate inflammatory injury” [1] and “amongst … the most devastating afflictions on the human body” [2]. Thanks to improvements in the management of severe burns, as well as public health and infrastructural advances [3], mortality due to burns has dropped substantially in the past half century [4]. Current American and Australian in-hospital death rates stand at 3% and 2%, respectively [5, 6]. Yet burns remain one of the most common types of trauma [4, 7], particularly in children, whose developing psychomotor skills, poor spatial awareness and exploratory behaviour place them at increased risk of injury [8].

In the US and Australia, children constitute more than one third of all burns-related hospital admissions [5, 6]. Admissions, however, capture only a small percentage of the true magnitude of burn injuries in children, as between 87% and 93% of paediatric burns are treated exclusively as outpatients [9, 10]. This is attributable, in large part, to the exceeding rarity of severe life-threatening burns in high-income countries. At one of Australia’s largest tertiary paediatric burns centres, over 62% of patients present with wounds covering less than 1% of their total body surface area (TBSA), and more than 90% of all burns are thermal in origin (i.e., scalds, contact burns, flame burns or radiant heat burns) [9]. The predominant focus in modern paediatric burns care, therefore, is no longer the treatment of severe burns and their life-threatening systemic effects, but rather the improvement of functional and cosmetic outcomes in small-to-medium-sized thermal wounds.

In recent decades, the acute management of such injuries has been advanced by innovations such as early excision and grafting [11,12,13,14], skin substitute technologies [15,16,17,18] and silver-impregnated dressings [19]. Nevertheless, complications including scar formation [20], contractures [21] and pain [22] still commonly affect children who have sustained burns. In particular, hypertrophic scarring, which is defined as the formation of raised scars within the boundaries of a wound, occurs in high proportions of burns patients (with a reported prevalence ranging from 32% to 72%) [23]. For children especially, the long-term physical and psychological consequences of these scars can be devastating [24]. In addition to their effects on appearance, self-esteem and social acceptance [25,26,27,28], they can lead to contractures that impair the range of motion and function as a child grows, necessitating recurrent surgical operations to release the scar tissue [21].

The facilitation of wound closure represents one of the central aims of acute burns treatment. Prompt wound closure is essential for the prevention of scarring, as there has long been a well-understood relationship between time to re-epithelialisation and scar formation. A widely held model that was first described by Deitch et al. [29] and later supported by others [30, 31] identified the 3-week mark as the critical time point in the healing process with regard to scarring. Burns that fully re-epithelialise before this point have a low risk of developing hypertrophic scars (and an especially low risk if healed within 2 weeks), whilst those requiring greater than 3 weeks are highly likely to scar. Although more recent research has somewhat challenged this doctrine by finding lower rates of scarring amongst the latter group than previously reported [32]—a change some authors attribute anecdotally to the increasing use of silver-impregnated dressings [31]—burns clinicians still overwhelmingly agree that prolonged healing is a major predictor for scar formation and regard any methods aimed at accelerating re-epithelisation as worthy of consideration.

Time to re-epithelialisation is closely tied to burn depth, of which there are four broad classifications [33]. In superficial burns, only the epidermal layer of the skin is affected. Superficial partial-thickness and deep dermal partial-thickness burns extend to the papillary and reticular layers of the dermis, respectively. Burns involving the entirety of both the epidermis and dermis are categorised as full- thickness. Superficial partial-thickness burns tend to heal spontaneously within 2 weeks, whilst deep dermal partial-thickness burns exhibit more prolonged healing, typically taking 3 to 5 weeks to fully re-epithelialise. Spontaneous wound closure is impossible for full-thickness burns, which heal exclusively at the margins by scarring. The delay or inhibition of the healing process in deeper burns stems in large part from the destruction of adnexal structures in the reticular dermis. These structures, which include hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands, serve as reservoirs of keratinocytes, which can repopulate zones of cellular damage [34]. Since deeper burns are associated with significant scarring [29], they are almost always treated with debridement and grafting [35].

Burns are dynamic injuries that are vulnerable to significant changes in size, depth and severity due to a process known as burn wound conversion. This phenomenon is best understood by reviewing Jackson’s burn wound model [36], which holds that thermal injuries are characterised locally by three concentric zones. The core zone of coagulation contains irreversibly destroyed necrotic tissue. By contrast, the outermost zone of hyperaemia is marked by increased blood flow and inflammation but will invariably recover. It is within the intermediate zone between these two, the zone of stasis, that appropriate management is most vital. Tissue here remains at least temporarily viable, but if the burn is not adequately treated, may undergo progressive cellular damage and death that will result in recruitment into the zone of coagulation. A complex interplay of pathological mechanisms underlies this process.

The initial thermal insult results in a prolonged inflammatory reaction characterised by the accumulation of neutrophils [37, 38]. In addition to releasing harmful cytokines and reactive oxygen species associated with collagen denaturation, keratinocyte apoptosis and DNA damage [37, 39], these neutrophils adhere to the endothelial lining of local blood vessels [40], leading to vascular plugging. Leukocyte adherence, in combination with increased vascular permeability and reduced interstitial hydrostatic pressure [41, 42], also contributes to oedema formation [43], which itself significantly impairs perfusion to the burn wound. Local circulation is further compromised by microvessel thrombosis arising from a peak in hypercoagulability that occurs 2 to 3 hours following injury [44]. Finally, oxidative stress, linked with over-activity of xanthine oxidase and NADPH oxidase, damages cellular proteins, nucleic acids and lipids central to the healing process [45, 46]. Subsequent expansion of the depth and surface area of a burn can continue for up to 5 days post-injury [47]. Adequate first aid and the application of appropriate dressings may alleviate some of these factors [48], but no techniques have yet been found that definitively minimise burn wound progression [49].

Even more prevalent and difficult to prevent than scarring, pain persists as one of the greatest unmet challenges in burns management [50]. Despite the development of sophisticated analgesic protocols, unrelieved pain continues to be reported at high rates amongst burns patients, often ranking as their most frequent complaint [51]. The risks of undertreated pain are enormous: in addition to causing intense momentary suffering, anxiety and distress, it can contribute to delayed healing [52] and the development of long-term sensory disturbances [53,54,55], chronic pain [50] and debilitating psychological issues [56, 57]. Notably, the highest levels of pain intensity and undertreatment are associated with procedural pain resulting from dressing changes and other interventions [58,59,60].

A number of alternative or adjunct therapies have been proposed to help facilitate the healing process, decrease burn wound progression and minimise pain [47]. One promising approach is negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), a technique that involves the use of a vacuum device to establish subatmospheric pressures through occlusive dressings over a wound site [61, 62]. Also known as vacuum-assisted closure, topical negative pressure, subatmospheric pressure and reticulated open cell foam therapy [63], NPWT shares the same basic principles as other medical therapies that have been in use for well over a century [64,65,66], but the current form of the technology, characterised by the maintenance of an evenly distributed vacuum through foam or gauze, first became commercially available in 1995 [67].

Since then, NPWT has become widely accepted in the world of wound management, particularly in the context of diabetic ulcers [68], open abdomens [69, 70], sternal wounds [71], open fractures [72] and haemangiomas [73]. Although the exact mechanism of action of NPWT is not yet fully understood, it is known to exert several effects on the local tissue environment. Among the most notable is a rise in extracellular pressure [74, 75]. This seemingly paradoxical trend is likely a result of tissue macrodeformation: as air is evacuated from the NPWT foam or gauze, the volume of the packing material decreases, consequently compressing the adjacent tissue. NPWT is believed to aid the healing process specifically by inducing wound contraction [76], generating microdeformational changes that stimulate cellular proliferation and neovascularisation [77,78,79], evacuating oedema fluid that adversely affects the local microvasculature, [80, 81] extracting toxins and bacteria [62, 82, 83], and preventing desiccation of the wound environment [63, 84].

NPWT has been employed at various stages in the management of burns, with the vast majority of the published literature focusing on its role in securing skin grafts [85,86,87]. Its efficacy as a primary treatment in the setting of acute burns, however, remains controversial [88]. A limited body of research has produced compelling evidence that thermal injuries managed acutely with NPWT demonstrate improved outcomes.

Morykwas et al. [89] were amongst the first to study the efficacy of NPWT in the acute management of burn injuries. In a porcine model, they created bilateral flank partial-thickness burns and applied NPWT to the burns on one side. Compared to the contralateral controls, burns treated with NPWT in the first 12 h following injury showed significantly reduced depth, cellular inflammation and collagen denaturation on histological analysis. The effect of NPWT on burn depth did not vary significantly with treatment duration. Applications of 5 days were no more efficacious than those spanning 12 or 6 hours.

The first human study to focus exclusively on NPWT for acute burns [90] likewise involved a comparison of differently treated bilateral thermal injuries. In seven patients presenting with bilateral partial-thickness hand burns, the more intensely injured hand underwent NPWT whilst the less injured hand received silver sulfadiazine. Daily measurements of wound perfusion in the first 3 days post-burn revealed a significant temporal decrease in blood flow in hands treated with silver sulfadiazine, but no such decrease in the hands given NPWT. Furthermore, the latter were significantly better perfused at days 2 and 3, and showed a clinically observable reduction in oedema formation. Healing times, however, were not reported. A prospective multicentre study with a similar design and a slightly larger sample size (n = 11) also found that the application of NPWT was associated with a greater reduction in oedema and increased perfusion compared to conventional silver-based therapy [91].

The remainder of the literature consists of a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews published over the past 13 years. Molnar et al. [49] described the case of a deep partial-thickness burn to the hand and forearm that fully re-epithelialised after 10 days following the application of NPWT. A comparison of the NPWT-treated burn with a less severe burn to the patient’s shoulder, which received standard therapy, revealed that NPWT yielded functionally and cosmetically superior results, with less hyperaemia and better skin quality. Another case report detailed the use of NPWT in a 54% TBSA full-thickness burn sustained by a civilian in the Iraqi war zone [92]. Although burns of this severity were typically fatal in Iraq, the patient survived his injury and was eventually discharged home. The authors concluded that the NPWT played a significant role in his survival.

The sole existing study to investigate the effect of NPWT on acute burns in children is a retrospective review by Ren et al. [93]. In a cohort of 29 paediatric patients, 22 of whom were undergoing treatment for burn injuries, the therapy was believed to accelerate wound granulation and decrease the number of required dressing changes, though the study did not include a control group and quantitative data on granulation tissue formation were not provided. Additionally, the authors failed to specify several salient details regarding their use of NPWT, including how long post-burn it was initially administered, whether it was given in combination with silver dressings, and the specific gauge pressure and duration of each NPWT application. Nevertheless, the lack of adverse events, with no recorded episodes of bleeding or abnormally elevated pain, attested to the safety of NPWT in the paediatric population.

Absent from the literature, however, are any high-powered trials with appropriate outcome measures comparing NPWT to standard acute burns management. The only published randomised controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the role of subatmospheric pressure in the management of acute burns was provided courtesy of Honnegowda et al. [94]. In their trial involving 50 adolescents and adults with thermal burns under 40% TBSA, half of the participants were allocated to intermittent NPWT and the other half to 5% povidone iodine gauze dressings. Wound biopsies collected at days 0 and 10 were subjected to a series of histological and biochemical analyses. The results revealed that the burns that underwent NPWT exhibited a richer, more stable extracellular matrix, less oxidative stress, an environmental pH more conducive to wound healing, and better overall granulation tissue deposition, angiogenesis and cellular infiltrate.

Although this trial shed significant light on the biochemical effects of NPWT, its focus on surrogate endpoints rather than validated patient-centred outcomes limited the clinical applicability of its findings. Additionally, the comparator control group was managed with betadine dressings not traditionally considered standard treatment in most developed countries. The study was further constrained by the time points of its data collection, which would fail to capture the full duration of re-epithelialisation for the majority of non-superficial burns.

The most recent Cochrane systematic review [95] on the application of NPWT in acute thermal injury, published in 2014, listed an earlier RCT that commenced in 2004. All available information on this trial is confined to a single conference abstract with interim data [96]. In the reported patient cohort, comprising a total of 23 adults presenting with bilateral partial-thickness hand burns, the NPWT-treated hands showed significantly reduced burn size at days 3 and 5 post-burn, but no difference at day 14. However, due to missing data (with a completed study never published in full) as well as several methodological limitations, the authors of the Cochrane review deemed the study to be at high risk of bias [95].

To address this gap in the literature, a pilot study was undertaken in 2015 at a paediatric burns outpatient department (OPD). In a sample of 20 children with acute burns, half were given a combination of NPWT and silver-impregnated dressings whilst the other half received silver dressings alone. Preliminary data revealed that the NPWT group exhibited moderately faster healing and reported lower pain scores [97]. More broadly, it demonstrated that NPWT could function as a feasible and safe addition to standard acute paediatric burns management and provided strong support for the development of a larger RCT.

Methods/design

Hypothesis and objectives

The central aim of this trial is to investigate the efficacy of NPWT as an adjunct to standard therapy in the treatment of paediatric burns. The research will measure the effects of NPWT on time to re-epithelialisation, pain and burn wound progression, and determine whether it produces outcomes superior to those of standard therapy alone. Based on data from a pilot study, it is hypothesised that NPWT will accelerate healing and reduce levels of pain and pruritus between dressing changes. Removal and re-application of the NPWT system is not expected to cause significantly more pain than standard dressing changes. In terms of the impacts on overall costs, it is suspected that NPWT may increase resource usage and costs in the acute phase of treatment, but, by virtue of faster re-epithelialisation and reduced scar formation, curb the personnel and material costs required for long-term scar management.

Study design

This prospective RCT will be a superiority trial involving two parallel treatment arms: active control and intervention. Participants will be monitored throughout the course of the acute phase of their management, up until the point of healing, and then examined at 3- and 6-month follow-ups to assess the long-term outcomes of their burns. The different phases of the trial, and the measurements taken at each, are summarised in the study design flowchart (Fig. 1) and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) figure (Fig. 2). The SPIRIT checklist is provided in Additional file 1.

Study setting

Patient recruitment will take place at a large metropolitan children’s hospital that serves as the sole provider of quaternary paediatric burns care for a region with a population of 4.5 million people.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

All paediatric burns patients presenting to the hospital’s emergency department (ED) or burns OPD will be considered for eligibility. Children will satisfy the inclusion criteria if they are under 17 years of age, possess a thermal burn covering <5% of their TBSA and present within 7 days of their injury. Exclusion criteria include burns that are located on the face or deemed by clinicians to be trivial in nature (i.e., not in need of further treatment). The eligibility criteria are listed in Table 1.

Recruitment

All patients presenting to the ED or burns OPD with acute burns will be consecutively assessed for eligibility until the completion of recruitment. Nursing and surgical staff will identify eligible patients. In the ED, clinicians will first request permission from caregivers before inviting an investigator to approach them. If presenting to the burns OPD, potential participants will be approached only if they indicate a willingness to take part in research on an initial intake questionnaire.

An investigator will seek informed caregiver consent and child assent (for children 6 years and above) following the provision of verbal and written participant information. Once consent has been obtained, the patient will be randomised to one of the two treatment arms.

Interventions

Patients in the control group will receive the same standard dressings provided to all patients presenting to the burns OPD, which include a combination of Acticoat™ (Smith & Nephew, Hull, UK) and Mepitel™ (Mölnlycke Healthcare, Mikkeli, Finland), secured with Hypafix™ (BSN Medical, Hamburg, Germany). Likewise, the intervention group will first have their wounds dressed with Acticoat™ and Mepitel™. They will then additionally receive NPWT via the following protocol.

After applying the Acticoat™ and Mepitel™, clinicians will pack the burn with 10–20 layers of Kerlix™ (Medline Industries, Northfield, US). This antimicrobial gauze permits the vacuum to be distributed evenly across the entire wound site. In addition to their antimicrobial and moisturising properties, the silver-impregnated dressings will also serve as a wound contact layer, preventing encroachment of the Kerlix™ into the damaged tissue. An airtight seal will be generated via an adhesive film drape, to which tubing will be attached to connect the wound environment to a RENASYS TOUCH™ device (Smith & Nephew, Hull, UK). Suction will be set at a continuous subatmospheric pressure: 80 mmHg will be employed as the standard setting, but clinicians will be free to apply instead 40 mmHg in cases where ischaemia might be a concern (e.g., children under 1 year old with digit or extremity burns). Continuous pressures will be used in favour of intermittent cycles since past research showed that intermittent modes lead to elevated pain and the formation of undesirable granulation tissue [98]. The portability of the RENASYS TOUCH™ device, which can be carried around by children as young as 2 years of age in a custom-made pack, will allow patients to return to their everyday activities while still receiving NPWT.

All interventions will be carried out by burns clinicians with extensive experience in the application of dressings and NPWT. Following their initial presentation, participants will return to the OPD 3 to 5 days later for a change of dressings and, for those in the intervention group, a replacement of their NPWT system. To alleviate any additional pain from the removal of the adhesive drape, the clinicians replacing the NPWT apparatus will apply Niltac™ (ConvaTec, Greenlane, NZ), a silicone-based spray that can effectively dissolve the film and ease extraction. Participants will continue to present to the burns clinic every 3 to 5 days for dressing and NPWT changes until the wound is fully re-epithelialised or until grafting is required.

Randomisation

To accommodate the different scoring scales that will be used to assess pain, randomisation will be stratified by age into three groups: 0 to 3 years, 4 to 7 years, and 8 to 16 years. Allocation to the control arm and intervention arm of the study will occur at a 1:1 ratio. A random sequence will be generated by the trial statistician using the permuted block method with a random block size of either four or six participants. The statistician will then upload this sequence to the central randomisation module on the Research Electronic Data Capture application (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, US). REDCap ensures allocation concealment by prohibiting investigators from viewing the sequence. Access is limited to an external administrator, who manages the server on which the module is hosted. Treatment allocations are assigned only after participants have been successfully enrolled and entered into the REDCap database. Randomisation will continue until each treatment arm has a minimum of 52 participants.

Blinding

The nature of the interventions precludes full blinding, but a number of key assessments will be blinded to minimise performance bias. By necessity, treating clinicians will be aware of group allocation throughout the duration of the participants’ care until the point of healing. Clinical judgements of re-epithelialisation, therefore, will not be blinded, but the use of 3D photographs will allow for a later review by a panel of blinded assessors. These assessors will not be provided any details pertaining to the participants’ management. If there any discrepancies, the blinded measures (or the majority thereof) will supersede those taken by clinicians.

Skin and scar assessments performed at 3- and 6-month follow-up appointments will also be blinded, as the clinical evaluators will have no knowledge of participants’ acute care. To reduce the risk of performance bias further, ultrasound images taken at these follow-ups will be reviewed by blinded assessors, who will measure scar and wound site thicknesses.

Primary outcome measure

Time to re-epithelialisation

The primary outcome will be time to full re-epithelialisation, as measured by the number of days from the injury to 95% re-epithelialisation of the burn wound. Percentage re-epithelialisation will be assessed at every clinical visit using multiple methods. A treating consultant will first perform an examination and record their assessment. Digital 3D photographs will then be taken of the burn using the 3DLife Viz II (Quantificare, Valbonne, France) and the D400 3D (Intel, Santa Clara, US) cameras. These photographs will be analysed using the software programs DermaPix (Quantificare, Valbonne, France) and 3D WoundCare (GPC, Swansea, UK), respectively, and undergo blinded review by a panel of three burns clinicians.

Secondary outcome measures

Pain

Pain intensity will be assessed at various time points throughout the participants’ management. At their first clinical visit, baseline pain measures will be recorded immediately prior to and following dressing applications. The same measures will be repeated before and after dressing changes at every subsequent clinical visit until the burn is considered fully re-epithelialised.

A variety of measures and age-dependent scales will be utilised to assess pain. Nurses will provide an observational rating using the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) scale, which is accepted as a valid and reliable tool for assessing trauma-related pain behaviours in preverbal children [99, 100]. Children aged 4 to 7 years will be asked to self-report their pain using the Revised Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) and those aged 8 years and older will self-report their pain using a numerical rating scale (NRS).

There is a large volume of literature demonstrating the validity and reliability of the FPS-R in children as young as 4 years old [101, 102]. For children aged 8 years and older, both the NRS and a visual analogue scale are well-validated tools [103, 104], but several comparison studies have expressed a preference for the NRS, which is associated with higher levels of responsivity, adherence and ease of use in the assessment of pain intensity among adults [105, 106]. Furthermore, the NRS allows for greater consistency throughout the full duration of the trial, as the two skin/scar assessment scales employed at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups both include numerical pain ratings.

To supplement the above pain ratings, investigators will additionally document the type and dosage of all analgesic medications administered to patients by health professionals or parents during the days on which they present to the clinic.

Pruritus

Itch severity will be measured concurrently with pain intensity. Unlike pain, emotional health, physical function and mobility, pruritus is one of the few domains in which parental and child perceptions significantly differ among paediatric burns patients [107]. As such, self-reports will be sought wherever possible. The only self-reporting itch scale that has been validated in children is the Itch Man Scale, which is recommended in children over the age of 5 years [108].

For patients too young to comprehend and cooperate with self-reporting scales, caregivers will be asked to perform an observational assessment using the Toronto Paediatric Itch Scale. This tool, which rates pruritus behaviours on a scale of 0 (absence of itch) to 3 (severe itch with significant disruption), has been found to assess itch severity in children aged 5 years or less with reasonable validity and reliability [109].

Pain and itch at home

Due to the multi-day durations of NPWT and silver-impregnated dressing treatments, measurements of pain and pruritus will be undertaken not only in the clinic but also at home, where most of the patients’ time undergoing their respective therapies will be spent. Caregivers will be contacted via text messages 24–48 h after every dressing application or change with a link to an online survey generated on REDCap. The survey will be automatically modified according to patient age to provide the appropriate pain and itch scales.

Retrospective reporting and recall bias are frequent risks associated with more traditional take-home questionnaires, with major implications for the validity of the outcomes they provide. [110,111,112] Online data collection via SMS notifications offers a valid alternative capable of prompting real-time assessments with a very high response rate and reduced management burden [113]. Moreover, any retrospective reports can be easily identified by their time stamps and evaluated accordingly.

If caregivers fail to complete the survey following the first message, they will be sent reminders every 24 h until they either submit their responses or attend their next clinical appointment. For those not in possession of a mobile phone or not agreeable to receiving research-related text messages, investigators will offer to send the surveys to their preferred email account, call their landline to collect the data verbally or, as a last resort, supply paper questionnaires.

Wound depth and progression

In addition to the treating consultant’s clinical assessments of burn depth and size, laser Doppler imaging (LDI) will be employed to help evaluate the extent of wound progression within burns. LDI measures blood perfusion, rather than directly assessing wound depth, but it is still widely considered to be a highly effective and accurate diagnostic tool for burn depth assessments [114]. As progression of wound depth and size is known to take place within the first 4 to 5 days post-burn [47, 115], LDI will be performed only at patients’ initial presentation and their first follow-up 3 to 5 days later. For each scan, investigators will record flux maximum, minimum, mean and standard deviation.

Treatment satisfaction

Clinicians in the burns OPD have observed anecdotally that older children and adolescents tend to be less tolerant of NPWT than younger patients. To evaluate quantitatively attitudes toward NPWT and how they vary with age, treatment satisfaction will be assessed at every clinical visit via the use of an 11-point NRS (0 = not at all satisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied). As with the NRS for pain, caregivers will provide an observational measure for children up to the age of 7 years, whilst those 8 years and older will self-report. Caregivers of all children will be asked to rate their own satisfaction with the treatment as well.

Physical function

Participants’ physical function while undergoing treatment will be assessed by patients and/or caregivers at every clinical visit, also via an 11-point NRS (0 = not at all easy to move; 10 = extremely easy to move).

Ease of management

The treating nurse will be surveyed on their views of the interventions after each baseline visit and change of dressings. They will specifically assess ease of removal and application, using another 11-point NRS (0 = not at all easy to remove/apply; 10 = extremely easy to remove/apply).

Scar and skin assessments

At 3 and 6 months following the burn injury, face-to-face follow-ups will be completed with all participants to conduct skin or scar reviews in conjunction with occupational therapy.

Ultrasound will be used to measure the thickness of the healed wound or scar. Scans will be taken centrally at each site of interest with the BT12 Venue 40 MSK ultrasound machine (General Electric, Little Chalfont, UK). The investigators will record and calculate an average of three thickness measurements within the central area at the time of the scan. These measurements will be compared to those taken from scans of healthy unburned skin contralateral to the site of the burn. Digital copies of the scans will be saved for later evaluations by blinded reviewers.

An objective quantification of the lightness, erythema, and pigmentation of the healed wound or scar will be obtained using the DSM II ColorMeter (Cortex Technology, Hadsund, Denmark). In paediatric studies, the device has exhibited high levels of inter-rater reliability [116], including among children with burn scars [117]. At each follow-up, two measurements will be taken of both the site of interest and a region of healthy skin for comparison.

The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) will also be completed with the child (if over the age of 8 years) and caregiver. As a scar severity evaluation tool, the POSAS is both reliable and feasible [118,119,120], with an observer scale that shows adequate reliability in the assessment of scar appearance in children [117]. Another instrument, the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile (BBSIP), will be used to measure scar patients’ physical and sensory symptoms as well as their health-related quality of life. Developed primarily for children, the BBSIP has undergone preliminary validation in paediatric patients at the participating burns centre [121].

Resource use and costs

Resource usage (and costs) for the care of each patient will be recorded from the perspective of the health service consistent with prior studies in the field [122, 123]. This will include details of the trial interventions, including the number of clinical visits, the duration of each visit, the dosages of analgesic medications prescribed, the quantity of dressings and NPWT products used, and associated labour time. Resource use will be costed at market rates (e.g., clinician time attributable to each participant will be costed based on relevant state-award salary rates). For patients requiring subsequent scar management, details of scar management (including scar interventions and associated clinician labour time) will also be recorded for each patient for the duration of the trial.

Grafting

With the inclusion of deep dermal partial-thickness and full-thickness burns in the eligibility criteria, it is anticipated that some participants will ultimately require skin grafting to achieve wound closure. All surgical procedures will be documented by investigators, but data collection will be discontinued for these patients at the point of grafting. Any data obtained prior to grafting will be included in the final analysis following an intention-to-treat methodology.

Adverse events

If a patient experiences an adverse event such as an infection or allergic reaction during the trial, investigators will record the event (even if not directly related to the child’s burn) and document any changes made to the child’s clinical care to address the issue. Should a consultant conclude that a particular dressing is not appropriate for a participant’s care, even in the absence of an adverse event, they will be free to select an alternative dressing. In both scenarios, data collection and analysis will adhere to intention-to-treat principles.

Wound exudate collection and analysis

Wound exudate has been increasingly recognised as a potentially rich source of information about the burn wound microenvironment [1]. Theoretically, NPWT is the ideal instrument for collecting this fluid. It extracts exudate directly from the interstitium and stores it in disposable canisters. Practically, however, the NPWT canisters have been engineered, for safety, to preclude any direct access to the collected exudate.

To obtain this fluid, therefore, investigators will inspect the used suction tube connected to the canister at every dressing change after the NPWT apparatus is replaced. If there is any visible wound aspirate, the tubing will be punctured so that the fluid can be drained into collection tubes. At the end of the clinical visit, the samples will be centrifuged at 855× relative centrifugal force for 5 minutes and frozen in aliquots at −80°C.

Once all the samples have been collected, they will be processed for SWATH™ mass spectrometry analysis, using techniques described previously [124]. Briefly, a 60-μg aliquot of each sample will be digested by trypsin, desalted, concentrated, and analysed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in data-independent acquisition mode for peptide identification and SWATH™ acquisition mode for peptide abundance. An existing peptide spectral ion library [125] will be used to identify the peptide products and generate proteomic profiles of the microenvironments of the different wounds. These profiles will be compared against one another as well as the proteomic profiles of paediatric burn blister fluid described previously by Zang et al. [125, 126]

The remainder of the samples will be subjected to more targeted assays to assess their levels of specific cytokines and other factors involved in the processes of burn wound conversion and healing. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) will be employed to detect markers of neovascularisation, re-epithelialisation and inflammation (e.g., VEGF, FGF-2, EGF, IL-8 and TNF-α). If sufficient quantities of exudate are collected, the assays will help to determine how these factors vary with time, depth and burn aetiology.

Sample size

The sample size was derived from the primary endpoint, time to re-epithelialisation. Previous burns research has reported a mean healing time with standard Acticoat™ therapy of 12.4 days (SD = 5.4) [127]. In light of findings by Deitch et al. [29] and Cubison et al. [30] that showed healing times under 10 days post-burn were associated with no hypertrophic scarring, the investigators considered that a 3.4-day reduction in time to re-epithelialisation would likely represent a clinically meaningful difference. Therefore, the study will aim to recruit a minimum of 104 participants for >80% power (assuming up to 20% drop-out and a significance level of 0.05). In 2017, approximately 1100 patients presented to the OPD for burns treatment. Of these, more than 90% satisfied the inclusion criteria of the present study. Therefore, it is expected that recruitment will be completed within a span of 9 months.

Data collection and management

Investigators will input data directly into the REDCap application via an electronic tablet. The application is hosted on a secure firewall-protected server at the research institute affiliated with the burns clinical unit. REDCap generates an audit trail that tracks all user activity, including data entry, manipulation and exportation. Any data exported for statistical analysis will be stored on a password-protected computer within the research institute. Access to passwords and codes will be limited to investigators involved in the trial. If any researcher leaves the project, all passwords will be replaced.

Data analysis

Conventional descriptive statistics will be used to describe the characteristics of the sample.

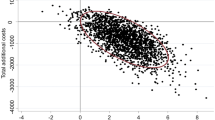

The potential effect of time to treatment, burn depth, burn TBSA, mechanism of injury, anatomical location of the burn and skin type will also be tested against primary and secondary measures in univariate analyses. Variables with p < 0.1 will be included as covariates in the primary and secondary analyses. Sensitivity analyses will also be conducted without adjustment for covariates.

Generalised linear (mixed) models will be prepared to examine primary and secondary outcomes across time and between groups, with patients as random effect where analyses include repeated measures within a patient. If mixed models do not converge with patient as a random effect, robust variance estimates for cluster-correlated data will be used [128]. For outcomes with repeated measures, the fixed effects of time, group and interaction time by group will be tested. Data will be analysed as intention-to-treat (primary analysis) and on a per protocol basis (sensitivity analysis) if deviations from the protocol occur. Missing data will be handled using multiple imputation where appropriate. Significance will be set at 0.05. Statistical analyses will be performed using Stata (StataCorp LLC College Station, TX:) or SPSS (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Discussion

Over the past two decades, NPWT has been extensively applied and studied in the management of a wide variety of wounds, even prompting some authors to remark that it has “overwhelmed the wound-healing world” [129]. It is all the more surprising, then, that so little research has been conducted investigating the efficacy of the technique in the acute management of burns. In the limited volume of literature that does exist, there is promising evidence to suggest NPWT may reduce ischaemia, oedema formation and wound progression [49, 89,90,91]. However, the constraints of the animal model studies, case reports and retrospective studies that comprise the bulk of this literature cast substantial doubt on the applicability of their findings. To date, no results from appropriately powered RCTs with patient-centred outcomes have been published comparing NPWT to standard acute burns management [95, 130].

Furthermore, the underrepresentation of children in the NPWT literature (across all wound types, but in the context of acute burns particularly) overlooks a large segment of the burns patient population [5]. Children also tend to suffer disproportionately from some of the immediate and long-term risks that NPWT is believed to alleviate. It is believed that infants might be more sensitive to pain than adults [131], and the potential harms of hypertrophic scarring are far greater in patients still undergoing physical, social and psychological development [24].

Any attempts to extrapolate findings from the existing adult studies to a paediatric setting must be met with caution, not only due to the small sample sizes and methodological limitations of these trials, but also because young children differ markedly from adults in skin thickness and composition [132, 133], body surface area [134], and formation rates of granulation tissue [135]. The reluctance to employ NPWT in paediatric populations appears to stem from concerns about possible side effects, including bleeding, ischaemia and elevated pain [93]. However, reports of adverse events are rare in the literature, and the technique is widely regarded as safe when applied and monitored as per device instructions [136]. NPWT is known to cause pain at pressures greater than 125 mmHg [137], but this is well above the standard range preferred by the participating hospital. Anecdotally, the highest levels of pain experienced by paediatric patients undergoing NPWT are reported during removal of the adhesive film required to maintain the airtight seal. It is anticipated that with the application of Niltac™ prior to extraction, removing and re-applying the NPWT system will be no more painful than regular dressing changes. The overall risks of NPWT are, therefore, minimal, with most research focusing on the use of the therapy in children indicating that it is especially suited for paediatrics, as it reduces the frequency of procedures and allows for greater mobility than some standard dressings [138].

The trial was deliberately designed to serve as a pragmatic study of the efficacy of NPWT in the treatment of the broad spectrum of thermal burn injuries that routinely present to the participating ED and OPD. Especially for the latter, the burns seen over the course of even a single day tend to vary significantly in terms of first aid, prior treatment and time to presentation. For this reason, investigators have set a sample size that is large enough to account for the wide variability and allow for a statistical comparison of different groups.

The 7-day window for time to presentation was selected as it captures the majority of the OPD patient population. Although Morykwas et al. [89] found that NPWT was effective in their animal model only if administered within 12 h post-burn, there are strong reasons to believe that NPWT could continue to be of benefit to humans past this point. First and foremost are the pathophysiological differences between humans and animals, including the finding that the peak in post-burn oedema volume appears to occur later in humans than in non-human subjects [139,140,141,142]. Furthermore, multiple human studies have reported progression of burn surface area and depth over 4 to 5 days following injury [47], and high-protein oedema is known to remain in the interstitium for at least the first 7 days post-burn [139].

The range of assessments to be employed in this trial were selected for their reliability as well as the feasibility with which they could be carried out on paediatric patients. It is acknowledged that the age, size or distress of a patient may sometimes preclude researchers from completing certain assessments, such as 3D photography and LDI. To account for this potential limitation, additional measures of burn size, re-epithelialisation and depth will also be provided via the consultants’ clinical judgement.

Study significance

Following a pilot study that yielded promising results, this trial aims to investigate the efficacy of NPWT in the treatment of acute paediatric burn injuries. By measuring the impact of NPWT on re-epithelialisation, burn wound progression and pain, the study aims to address the gaps in the NPWT literature and determine whether the therapy warrants implementation as an adjunct to standard therapy.

Trial status

This manuscript represents the 15th version of the trial protocol, completed on 15 January 2019. Recruitment commenced on 2 May 2018 and is expected to conclude by 31 January 2019. At the time of writing, 103 participants have been recruited.

Abbreviations

- BBSIP:

-

Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile

- B/w:

-

Between

- DC:

-

Dressing change

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- FLACC:

-

Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability

- FPS-R:

-

Faces Pain Scale, Revised

- LDI:

-

Laser Doppler imaging

- NPWT:

-

Negative pressure wound therapy

- NRS:

-

Numerical rating scale

- OPD:

-

Outpatient department

- POH:

-

Point of healing

- POSAS:

-

Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SMS:

-

Short Message Service

- SWATH:

-

Sequential window acquisition of all theoretical fragment-ion spectra

- TBSA:

-

Total body surface area

References

Widgerow AD, King K, Tocco-Tussardi I, Banyard DA, Chiang R, Awad A, et al. The burn wound exudate-an under-utilized resource. Burns. 2014;41(1):11–7.

Lee KC, Joory K, Moiemen NS. History of burns: The past, present and the future. Burns Trauma. 2014;2(4):169–80.

Capek KD, Sousse LE, Hundeshagen G, Voigt CD, Suman OE, Finnerty CC, et al. Contemporary Burn Survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(4):453–63.

World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

Lincoln T, McInnes, Gong J, Gabbe B, Thomas T. Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand Annual Report: 1st July 2015-30th June 2016 [Internet]. Australian and New Zealand Burn Association [cited 2018 May 5]. Available from: https://anzba.org.au/assets/BRANZ_AnnualReport_Year8_FINAL_V2.pdf.

National Burn Repository 2017 Update Summary [Internet]. Chicago: American Burn Association; 2017. [cited 2018 May 5]. Available from: http://ameriburn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2017_aba_nbr_annual_report_summary.pdf.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia, 2011. Canberra: AIHW; 2016.

Emond A, Sheahan C, Mytton J, Hollen L. Developmental and behavioural associations of burns and scalds in children: a prospective population-based study. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(5):428–83.

Stockton KA, Harvey J, Kimble RM. A prospective observational study investigating all children presenting to a specialty paediatric burns centre. Burns. 2014;41(3):476–83.

Shields BJ, Comstock RD, Fernandez SA, Xiang H, Smith GA. Healthcare resource utilization and epidemiology of pediatric burn-associated hospitalizations, United States, 2000. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(6):811–26.

Janzekovic Z. Once upon a time ... how west discovered east. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(3):240–4.

Janzekovic Z. A new concept in the early excision and immediate grafting of burns. J Trauma. 1970;10(12):1103–8.

Herndon DN, Parks DH. Comparison of serial debridement and autografting and early massive excision with cadaver skin overlay in the treatment of large burns in children. J Trauma. 1986;26(2):149–52.

Herndon DN, Barrow RE, Rutan RL, Rutan TC, Desai MH, Abston S. A comparison of conservative versus early excision. Therapies in severely burned patients. Ann Surg. 1989;209(5):547–52 discussion 52-3.

Lagus H, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Bohling T, Vuola J. Prospective study on burns treated with Integra(R), a cellulose sponge and split thickness skin graft: comparative clinical and histological study--randomized controlled trial. Burns. 2013;39(8):1577–87.

Branski LK, Herndon DN, Pereira C, Mlcak RP, Celis MM, Lee JO, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Integra in primary burn management: a randomized pediatric clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(11):2615–23.

Heimbach DM, Warden GD, Luterman A, Jordan MH, Ozobia N, Ryan CM, et al. Multicenter postapproval clinical trial of Integra dermal regeneration template for burn treatment. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24(1):42–8.

Heimbach D, Luterman A, Burke J, Cram A, Herndon D, Hunt J, et al. Artificial dermis for major burns. A multi-center randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 1988;208(3):313–20.

Gee Kee EL, Kimble RM, Cuttle L, Khan A, Stockton KA. Randomized controlled trial of three burns dressings for partial thickness burns in children. Burns. 2015;41(5):946–55.

Bombaro KM, Engrav LH, Carrougher GJ, Wiechman SA, Faucher L, Costa BA, et al. What is the prevalence of hypertrophic scarring following burns? Burns. 2003;29(4):299–302.

Goverman J, Mathews K, Goldstein R, Holavanahalli R, Kowalske K, Esselman P, et al. Pediatric Contractures in Burn Injury: A Burn Model System National Database Study. J Burn Care Res. 2016;38(1):e192–e9.

de Jong AE, Bremer M, van Komen R, Vanbrabant L, Schuurmans M, Middelkoop E, et al. Pain in young children with burns: extent, course and influencing factors. Burns. 2013;40(1):38–47.

Lawrence JW, Mason ST, Schomer K, Klein MB. Epidemiology and impact of scarring after burn injury: a systematic review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2011;33(1):136–46.

McGarry S, Elliott C, McDonald A, Valentine J, Wood F, Girdler S. Paediatric burns: from the voice of the child. Burns. 2013;40(4):606–15.

Blakeney P, Partridge J, Rumsey N. Community integration. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(4):598–601.

Thompson A, Kent G. Adjusting to disfigurement: processes involved in dealing with being visibly different. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(5):663–82.

Rumsey N, Harcourt D. Visible difference amongst children and adolescents: issues and interventions. Dev Neurorehabil. 2007;10(2):113–23.

Lawrence JW, Rosenberg L, Rimmer RB, Thombs BD, Fauerbach JA. Perceived stigmatization and social comfort: validating the constructs and their measurement among pediatric burn survivors. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55(4):360–71.

Deitch EA, Wheelahan TM, Rose MP, Clothier J, Cotter J. Hypertrophic burn scars: analysis of variables. J Trauma. 1983;23(10):895–8.

Cubison TC, Pape SA, Parkhouse N. Evidence for the link between healing time and the development of hypertrophic scars (HTS) in paediatric burns due to scald injury. Burns. 2006;32(8):992–9.

Lonie S, Baker P, Teixeira RP. Healing time and incidence of hypertrophic scarring in paediatric scalds. Burns. 2016;43(3):509–13.

Hassan S, Reynolds G, Clarkson J, Brooks P. Challenging the dogma: relationship between time to healing and formation of hypertrophic scars after burn injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2013;35(2):e118–24.

Shakespeare PG. Standards and quality in burn treatment. Burns. 2001;27(8):791–2.

Shupp JW, Nasabzadeh TJ, Rosenthal DS, Jordan MH, Fidler P, Jeng JC. A review of the local pathophysiologic bases of burn wound progression. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(6):849–73.

Schiestl C, Meuli M, Trop M, Neuhaus K. Management of burn wounds. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23(5):341–8.

Jackson DM. The diagnosis of the depth of burning. Br J Surg. 1953;40:588–96.

Bucky LP, Vedder NB, Hong HZ, Ehrlich HP, Winn RK, Harlan JM, et al. Reduction of burn injury by inhibiting CD18-mediated leukocyte adherence in rabbits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(7):1473–80.

Hu Z, Sayeed MM. Activation of PI3-kinase/PKB contributes to delay in neutrophil apoptosis after thermal injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;288(5):1171–8.

Parihar A, Parihar MS, Milner S, Bhat S. Oxidative stress and anti-oxidative mobilization in burn injury. Burns. 2007;34(1):6–17.

Mileski W, Borgstrom D, Lightfoot E, Rothlein R, Faanes R, Lipsky P, et al. Inhibition of leukocyte-endothelial adherence following thermal injury. J Surg Res. 1992;52(4):334–9.

Lund T, Wiig H, Reed RK. Acute postburn edema: role of strongly negative interstitial fluid pressure. Am J Phys. 1988;255(5 Pt 2):H1069–74.

Onarheim H, Reed RK. Thermal skin injury: effect of fluid therapy on the transcapillary colloid osmotic gradient. J Surg Res. 1991;50(3):272–8.

Infanger M, Schmidt O, Kossmehl P, Grad S, Ertel W, Grimm D. Vascular endothelial growth factor serum level is strongly enhanced after burn injury and correlated with local and general tissue edema. Burns. 2004;30(4):305–11.

Isik S, Sahin U, Ilgan S, Guler M, Gunalp B, Selmanpakoglu N. Saving the zone of stasis in burns with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA): an experimental study in rats. Burns. 1998;24(3):217–23.

Till GO, Guilds LS, Mahrougui M, Friedl HP, Trentz O, Ward PA. Role of xanthine oxidase in thermal injury of skin. Am J Pathol. 1989;135(1):195–202.

Inoue H, Ando K, Wakisaka N, Matsuzaki K, Aihara M, Kumagai N. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on vascular hyperpermeability with thermal injury in mice. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5(4):334–42.

Schmauss D, Rezaeian F, Finck T, Machens HG, Wettstein R, Harder Y. Treatment of secondary burn wound progression in contact burns-a systematic review of experimental approaches. J Burn Care Res. 2014;36(3):e176–89.

Wood FM, Phillips M, Jovic T, Cassidy JT, Cameron P, Edgar DW. Water First Aid Is Beneficial In Humans Post-Burn: Evidence from a Bi-National Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147259.

Molnar JA, Simpson JL, Voignier DM, Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC. Management of an acute thermal injury with subatmospheric pressure. J Burns Wounds. 2006;4:e5.

Pardesi O, Fuzaylov G. Pain Management in Pediatric Burn Patients: Review of Recent Literature and Future Directions. J Burn Care Res. 2016;38(6):335–47.

Meyer WJ, Jeevendra Martyn JA, Wiechman S, Thomas CR, Woodson L. Chapter 64: Management of Pain and Other Discomforts in Burned Patients. Total Burn Care. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2018. p. 679–99.

Brown NJ, Kimble RM, Gramotnev G, Rodger S, Cuttle L. Predictors of re-epithelialization in pediatric burn. Burns. 2013;40(4):751–8.

McGrath PJ, Frager G. Psychological barriers to optimal pain management in infants and children. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(2):135–41.

Wollgarten-Hadamek I, Hohmeister J, Demirakca S, Zohsel K, Flor H, Hermann C. Do burn injuries during infancy affect pain and sensory sensitivity in later childhood? Pain. 2008;141(1–2):165–72.

Wollgarten-Hadamek I, Hohmeister J, Zohsel K, Flor H, Hermann C. Do school-aged children with burn injuries during infancy show stress-induced activation of pain inhibitory mechanisms? Eur J Pain. 2010;15(4):423.e1–10.

Saxe GN, Stoddard F, Hall E, Chawla N, Lopez C, Sheridan R, et al. Pathways to PTSD, part I: Children with burns. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1299–304.

Bakker A, Maertens KJ, Van Son MJ, Van Loey NE. Psychological consequences of pediatric burns from a child and family perspective: a review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(3):361–71.

Choiniere M, Melzack R, Rondeau J, Girard N, Paquin MJ. The pain of burns: characteristics and correlates. J Trauma. 1989;29(11):1531–9.

Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Hollinworth H. An international perspective on wound pain and trauma. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2003;49(4):12–4.

McGarry S, Elliott C, McDonald A, Valentine J, Wood F, Girdler S. “This is not just a little accident”: a qualitative understanding of paediatric burns from the perspective of parents. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;37(1):41–50.

Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(6):563–76 discussion 77.

Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(6):553–62.

Banwell PE, Musgrave M. Topical negative pressure therapy: mechanisms and indications. Int Wound J. 2006;1(2):95–106.

Meyer W, Schmieden V, Bier AKG. Bier’s hyperemic treatment in surgery, medicine, and the specialties: a manual of its practical application: Saunders; 1909.

Iusupov Iu N, Epifanov MV. Active drainage of a wound. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 1987;138(4):42–6.

Fay MF. Drainage systems. Their role in wound healing. AORN J. 1987;46(3):442–55.

Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. U.S. Patent No. 5,636,643 (1997 Jun 10).

Liu S, He CZ, Cai YT, Xing QP, Guo YZ, Chen ZL, et al. Evaluation of negative-pressure wound therapy for patients with diabetic foot ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:533–44.

Montori G, Allievi N, Coccolini F, Solaini L, Campanati L, Ceresoli M, et al. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy versus modified Barker Vacuum Pack as temporary abdominal closure technique for Open Abdomen management: a four-year experience. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):86.

Tolonen M, Mentula P, Sallinen V, Rasilainen S, Backlund M, Leppaniemi A. Open abdomen with vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction in patients with complicated diffuse secondary peritonitis: A single-center 8-year experience. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6):1100–5.

Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Sommella L, Tocco MP, Marvulli M, Magrini P, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy for patients with infected sternal wounds: a meta-analysis of current evidence. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(9):1119–23.

Blum ML, Esser M, Richardson M, Paul E, Rosenfeldt FL. Negative pressure wound therapy reduces deep infection rate in open tibial fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(9):499–505.

Fox CM, Johnson B, Storey K, Das Gupta R, Kimble R. Negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of ulcerated infantile haemangioma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31(7):653–8.

Kairinos N, Solomons M, Hudson DA. Negative-pressure wound therapy I: the paradox of negative-pressure wound therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(2):589–600.

Kairinos N, Solomons M, Hudson DA. The paradox of negative pressure wound therapy--in vitro studies. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;63(1):174–9.

Borgquist O, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M. The influence of low and high pressure levels during negative-pressure wound therapy on wound contraction and fluid evacuation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;127(2):551–9.

Scherer SS, Pietramaggiori G, Mathews JC, Orgill DP. Short periodic applications of the vacuum-assisted closure device cause an extended tissue response in the diabetic mouse model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(5):1458–65.

Potter MJ, Banwell P, Baldwin C, Clayton E, Irvine L, Linge C, et al. In vitro optimisation of topical negative pressure regimens for angiogenesis into synthetic dermal replacements. Burns. 2008;34(2):164–74.

Greene AK, Puder M, Roy R, Arsenault D, Kwei S, Moses MA, et al. Microdeformational wound therapy: effects on angiogenesis and matrix metalloproteinases in chronic wounds of 3 debilitated patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(4):418–22.

Yang CC, Chang DS, Webb LX. Vacuum-assisted closure for fasciotomy wounds following compartment syndrome of the leg. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2006;15(1):19–23.

Adamkova M, Tymonova J, Zamecnikova I, Kadlcik M, Klosova H. First experience with the use of vacuum assisted closure in the treatment of skin defects at the burn center. Acta Chir Plast. 2005;47(1):24–7.

Lancerotto L, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Mechanisms of action of microdeformational wound therapy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(9):987–92.

Morykwas MJ, Simpson J, Punger K, Argenta A, Kremers L, Argenta J. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of basic research and physiologic foundation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):121–6.

Banwell PE. Topical negative pressure therapy in wound care. J Wound Care. 1999;8(2):79–84.

Llanos S, Danilla S, Barraza C, Armijo E, Pineros JL, Quintas M, et al. Effectiveness of negative pressure closure in the integration of split thickness skin grafts: a randomized, double-masked, controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244(5):700–5.

Petkar KS, Dhanraj P, Kingsly PM, Sreekar H, Lakshmanarao A, Lamba S, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing negative pressure dressing and conventional dressing methods on split-thickness skin grafts in burned patients. Burns. 2011;37(6):925–9.

Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, Meredith JW, Owings JT. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002;137(8):930–4.

Kantak NA, Mistry R, Varon DE, Halvorson EG. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Burns. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44(3):671–7.

Morykwas MJ, David LR, Schneider AM, Whang C, Jennings DA, Canty C, et al. Use of subatmospheric pressure to prevent progression of partial-thickness burns in a swine model. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20(1):15–21.

Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, Winter W, Meissl G, Frey M. Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns. 2004;30(3):253–8.

Schrank C, Mayr M, Overesch M, Molnar J, Henkel VDG, Muhlbauer W, et al. Results of vacuum therapy (V.A.C.) of superficial and deep dermal burns. Zentralbl Chir. 2004;129:59–61.

Danks RR, Lairet K. Innovations in caring for a large burn in the Iraq war zone. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(4):665–9.

Ren Y, Chang P, Sheridan RL. Negative wound pressure therapy is safe and useful in pediatric burn patients. Int J Burns Trauma. 2017;7(2):12–6.

Honnegowda TM, Padmanabha Udupa EG, Rao P, Kumar P, Singh R. Superficial Burn Wound Healing with Intermittent Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Under Limited Access and Conventional Dressings. World J Plast Surg. 2016;5(3):265–73.

Dumville JC, Munson C, Christie J. Negative pressure wound therapy for partial-thickness burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12 [cited 2018 Jan 20]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006215.pub4.

Molnar J, Heimbach DM, Tredget EE, Hickerson WL, Still JM, Luterman A. Prospective randomized controlled mulitcenter trial applying subatmospheric pressure to acute hand burns: an interim report. Paris: 2nd World Union of Wound Healing Societies’ Meeting; July 18–23; 2004.

Storey K, Stockton K, McPike E, Kimble R. Negative pressure wound therapy on acute paediatric burns. Melbourne: ANZBA 39th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2015.

Malmsjö M, Gustafsson L, Lindstedt S, Gesslein B, Ingemansson R. The Effects of Variable, Intermittent, and Continuous Negative Pressure Wound Therapy, Using Foam or Gauze, on Wound Contraction, Granulation Tissue Formation, and Ingrowth Into the Wound Filler. Eplasty. 2012;12(5):42–54.

Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23(3):293–7.

Manworren RC, Hynan LS. Clinical validation of FLACC: preverbal patient pain scale. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29(2):140–6.

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–83.

von Baeyer CL. Children's self-reports of pain intensity: scale selection, limitations and interpretation. Pain Res Manag. 2006;11(3):157–62.

von Baeyer CL, Spagrud LJ, McCormick JC, Choo E, Neville K, Connelly MA. Three new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children's self-reports of pain intensity. Pain. 2009;143(3):223–7.

Miro J, Castarlenas E, Huguet A. Evidence for the use of a numerical rating scale to assess the intensity of pediatric pain. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(10):1089–95.

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(6):1073–93.

Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. 2011;152(10):2399–404.

Meyer W, Lee A, Kazis L, Li N, Sheridan R, Herndon D, et al. Adolescent survivors of burn injuries and their parents’ perceptions of recovery outcomes: do they agree or disagree? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3 Suppl 2):S213–20.

Morris V, Murphy LM, Rosenberg M, Rosenberg L, Holzer CE 3rd, Meyer WJ 3rd. Itch assessment scale for the pediatric burn survivor. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(3):419–24.

Everett T, Parker K, Fish J, Pehora C, Budd D, Kelly C, et al. The construction and implementation of a novel postburn pruritus scale for infants and children aged five years or less: introducing the Toronto Pediatric Itch Scale. J Burn Care Res. 2014;36(1):44–9.

Lane SJ, Heddle NM, Arnold E, Walker I. A review of randomized controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of hand held computers with paper methods for data collection. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6:23.

Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. BMJ. 2002;324(7347):1193–4.

Lauritsen K, Degl’Innocenti A, Hendel L, Praest J, Lytje MF, Clemmensen-Rotne K, et al. Symptom recording in a randomised clinical trial: paper diaries vs. electronic or telephone data capture. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(6):585–97.

Christie A, Dagfinrud H, Dale O, Schulz T, Hagen KB. Collection of patient-reported outcomes; − text messages on mobile phones provide valid scores and high response rates. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(52):1–5.

Shin JY, Yi HS. Diagnostic accuracy of laser Doppler imaging in burn depth assessment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns. 2016;42(7):1369–76.

Singh V, Devgan L, Bhat S, Milner SM. The pathogenesis of burn wound conversion. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(1):109–15.

van der Wal M, Bloemen M, Verhaegen P, Tuinebreijer W, de Vet H, van Zuijlen P, et al. Objective color measurements: clinimetric performance of three devices on normal skin and scar tissue. J Burn Care Res. 2012;34(3):e187–94.

Simons MGKE, Leung K, Tyack Z. Test-retest reliability of the POSAS, colorimeter, 3D camera and ultrasound. Sydney: International Society for Burn Injuries; 2014.

Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Tuinebreijer WE, Middelkoop E, Kreis RW, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):1960–7.

Simons M, Ziviani J, Thorley M, McNee J, Tyack Z. Exploring reliability of scar rating scales using photographs of burns from children aged up to 15 years. J Burn Care Res. 2012;34(4):427–38.

van der Wal MB, Tuinebreijer WE, Bloemen MC, Verhaegen PD, Middelkoop E, van Zuijlen PP. Rasch analysis of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) in burn scars. Qual Life Res. 2011;21(1):13–23.

Tyack Z, Ziviani J, Kimble R, Plaza A, Jones A, Cuttle L, et al. Measuring the impact of burn scarring on health-related quality of life: Development and preliminary content validation of the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile (BBSIP) for children and adults. Burns. 2015;41(7):1405–19.

Gee Kee E, Stockton K, Kimble RM, Cuttle L, McPhail SM. Cost-effectiveness of silver dressings for paediatric partial thickness burns: An economic evaluation from a randomized controlled trial. Burns. 2017;43(4):724–32.

Wiseman J, Simons M, Kimble R, Ware R, McPhail S, Tyack Z. Effectiveness of topical silicone gel and pressure garment therapy for burn scar prevention and management in children: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):72.

Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(8):1896–906.

Zang T, Broszczak DA, Cuttle L, Broadbent JA, Tanzer C, Parker TJ. The blister fluid proteome of paediatric burns. J Proteome. 2016;146:122–32.

Zang T, Broszczak DA, Broadbent JA, Cuttle L, Lu H, Parker TJ. The biochemistry of blister fluid from pediatric burn injuries: proteomics and metabolomics aspects. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2015;13(1):35–53.

Huang Y, Li X, Liao Z, Zhang G, Liu Q, Tang J, et al. A randomized comparative trial between Acticoat and SD-Ag in the treatment of residual burn wounds, including safety analysis. Burns. 2006;33(2):161–6.

Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–6.

Desai KK, Hahn E, Pulikkottil B, Lee E. Negative pressure wound therapy: an algorithm. Clin Plast Surg. 2012;39(3):311–24.

Gregor S, Maegele M, Sauerland S, Krahn JF, Peinemann F, Lange S. Negative pressure wound therapy: a vacuum of evidence? Arch Surg. 2008;143(2):189–96.

Goksan S, Hartley C, Emery F, Cockrill N, Poorun R, Moultrie F, et al. fMRI reveals neural activity overlap between adult and infant pain. Elife. 2015;4:e06356.

Birchenough SA, Gampper TJ, Morgan RF. Special considerations in the management of pediatric upper extremity and hand burns. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(4):933–41.

Stamatas GN, Nikolovski J, Luedtke MA, Kollias N, Wiegand BC. Infant skin microstructure assessed in vivo differs from adult skin in organization and at the cellular level. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;27(2):125–31.

Passaretti D, Billmire DA. Management of pediatric burns. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14(5):713–8.

Mooney JF 3rd, Argenta LC, Marks MW, Morykwas MJ, DeFranzo AJ. Treatment of soft tissue defects in pediatric patients using the V.A.C. system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:26–31.

Baharestani M, Amjad I, Bookout K, Fleck T, Gabriel A, Kaufman D, et al. V.A.C. Therapy in the management of paediatric wounds: clinical review and experience. Int Wound J. 2009;Suppl 1(6):1–26.

Borgquist O, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M. Wound edge microvascular blood flow during negative-pressure wound therapy: examining the effects of pressures from −10 to −175 mmHg. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):502–9.

Contractor D, Amling J, Brandoli C, Tosi LL. Negative pressure wound therapy with reticulated open cell foam in children: an overview. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(10 Suppl):S167–76.

Edgar DW, Fear M, Wood FM. A Descriptive Study of the Temporal Patterns of Volume and Contents Change in Human Acute Burn Edema: Application in Evidence-Based Intervention and Research Design. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37(5):293–304.

Caulfield RH, Tyler MP, Austyn JM, Dziewulski P, McGrouther DA. The relationship between protease/anti-protease profile, angiogenesis and re-epithelialisation in acute burn wounds. Burns. 2007;34(4):474–86.

Carvajal HF, Linares HA, Brouhard BH. Relationship of burn size to vascular permeability changes in rats. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149(2):193–202.

Demling RH, Mazess RB, Witt RM, Wolberg WH. The study of burn wound edema using dichromatic absorptiometry. J Trauma. 1978;18(2):124–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire staff of the Pegg Leditschke Children’s Burns Centre at the Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, for their expertise and support, and we extend special thanks to the children, families and clinicians who will take part in this research.

Funding

Funding for this study has been provided by Smith & Nephew in the form of a research grant awarded to the Queensland University of Technology. Smith & Nephew’s contact details: Namal Nawana (CEO), London, United Kingdom and Kingston upon Hull, United Kingdom. SMM is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (Australian government) fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable for protocol manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RK, BG and CCF participated in the design of the trial protocol. CCF composed the draft manuscript with significant input from BG. SMM and LC made substantial contributions to the descriptions of the statistical analyses and wound fluid studies, respectively. All authors critically reviewed the final manuscript and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol has been approved by the Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/17/QRCH/279) as well as the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committees (2,018,000,335/HREC/17/QRCH/279). Written informed consent will be obtained from the legal guardians of all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for a protocol manuscript. Investigators intend to present their results at national and international conferences, in addition to publishing them in peer-reviewed journals. Findings of note will be widely disseminated to relevant stakeholders.

Competing interests

Smith & Nephew’s involvement in this study is limited to their financial support. They have not contributed to the design of this protocol, and will have no part in the collection, storage, analysis or publication of any data. Investigators will have exclusive access to final trial datasets.

The lead researcher (CCF) has no financial interest in either the RENASYS TOUCH device or Smith & Nephew, and is a PhD student at the University of Queensland. BG, LC, SMM and RK declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

SPIRIT Checklist. Recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol (DOCX 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Frear, C.C., Griffin, B., Cuttle, L. et al. Study of negative pressure wound therapy as an adjunct treatment for acute burns in children (SONATA in C): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 20, 130 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3223-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3223-9