Abstract

Background

Evidence-based clinical practice is challenging in all fields, but poses special barriers in the field of rare diseases. The present paper summarises the main barriers faced by clinical research in rare diseases, and highlights opportunities for improvement.

Methods

Systematic literature searches without meta-analyses and internal European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN) communications during face-to-face meetings and telephone conferences from 2013 to 2017 within the context of the ECRIN Integrating Activity (ECRIN-IA) project.

Results

Barriers specific to rare diseases comprise the difficulty to recruit participants because of rarity, scattering of patients, limited knowledge on natural history of diseases, difficulties to achieve accurate diagnosis and identify patients in health information systems, and difficulties choosing clinically relevant outcomes.

Conclusions

Evidence-based clinical practice for rare diseases should start by collecting clinical data in databases and registries; defining measurable patient-centred outcomes; and selecting appropriate study designs adapted to small study populations. Rare diseases constitute one of the most paradigmatic fields in which multi-stakeholder engagement, especially from patients, is needed for success. Clinical research infrastructures and expertise networks offer opportunities for establishing evidence-based clinical practice within rare diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinical practice based on valid evidence is especially challenging in the field of rare diseases (RDs) [1], a group of diseases defined differently in several legislations. In Europe, diseases with prevalence equal to or lower that 5/10,000 inhabitants are considered rare [2]. In Asia, the definitions of RDs are < 1/10,000 inhabitants in Japan and Taiwan [3]. In the USA, a disease is considered rare if affecting fewer than 200,000 people, equivalent to about 6/10,000 inhabitants or less [4]. While some RDs are close to these prevalence thresholds, 10% to 20% are ultra-rare [5, 6]. The distinction between rare and ultra-rare diseases is important because of its implication in the assessment of the value of orphan medicinal products [7].

There are roughly 6000 clinically different RDs spread in all medical specialties, the largest groups being developmental defects of genetic origin, cancers, neurological diseases, systemic and rheumatologic diseases, and inborn errors of metabolism [6]. RDs are, therefore, a heterogeneous field, mostly composed of chronic and life-threatening diseases, the only feature in common being the rarity which jeopardises the performance of the research and development process when compared to common diseases [8]. This is a matter of concern, as RDs are recognised as a major health issue, and are the target of an active European Union policy [9,10,11,12]. Moreover, incentives to the drug and device industries have been put into place to boost the development of therapies for RDs in the USA in 1983 [13] and in the European Union in 2000 [2].

Recently, the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium (IRDiRC) has challenged the international research community with two major objectives: to develop the capacity to diagnose most RDs, and to establish 200 new or repurposed therapies for RDs by 2020 [14]. As of December 2015, a total of 118 orphan medicinal products have reached the market in Europe intended for about 107 diseases [15] and 432 orphan medicinal products have reached the market in the USA [16]. These results are good, but are far from meeting the needs of RD patients [17, 18]. Furthermore, the attrition of treatment options during the research and development process seems worse than with common diseases.

About 10% of the market authorisations for medicinal products for RDs are granted at a stage were the evidence is not yet firmly established through accelerated approval or conditional approval [19, 20]. Without such approvals, there is a need for the monitoring of patients treated with the new interventions for many more years. The concept of adaptive pathways has been proposed, which aims to grant marketing authorisations based on a lower weight of evidence justified by the claim that patients will have earlier access to treatment [21, 22]. Adaptive pathways are based on stepwise learning under conditions of acknowledged uncertainty, with iterative phases of data gathering and regulatory evaluations [23]. However, it has been criticised for lacking scientific support and ethical ground, and thus, for increasing uncertainty about the benefit-harm balance of new medicinal products [21, 22].

There is a need to build the evidence from basic research to bedside, through rigorous clinical research adapted to the intrinsic complexity of RDs [1]. The European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN) Integrating Activity (ECRIN-IA) projectFootnote 1 [24] has identified barriers for good clinical research within trials in general as well as regarding RDs, nutrition, and medical devices, and assessed how these barriers can be broken down in order to improve the production of evidence-based clinical research [25,26,27]. The aims of this paper are to summarise the main barriers faced by clinical research in the field of RDs and to highlight the opportunities for improvement at the European and international level (Table 1). These main barriers should be seen as additions to the barriers threatening all clinical trials, namely inadequate knowledge and understanding of clinical research and trial methodology; lack of funding; excessive monitoring; restrictive interpretation of privacy law and lack of transparency; overly complex or inadequate regulatory requirements; and inadequate clinical research infrastructures [25].

Methods

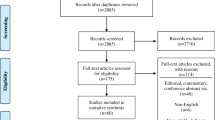

The present paper is based on personal ECRIN communications during four face-to-face meetings and six telephone conferences from 2013 to 2017, and systematic literature searches in May 2016 for appropriate articles using the following databases: The Cochrane Library (Wiley) (Issue 5 of 12, 2016) (including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)), CENTRAL, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED), and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE, U.S. Library of Medicine); MEDLINE (Ovid SP) (1946 to May 2016); EMBASE (Ovid SP) (1974 to May 2016); and Science Citation Index Expanded (1900 to May 2016), using different terms covering barriers, evidence-based medicine, and RDs. No meta-analyses were performed. The exact search strategy is provided in Additional file 1. A PRISMA flow diagram depicting the selection process and a PRISMA Checklist are provided in Fig. 1 and Additional file 2. Articles obtained from the systematic literature search, which were relevant to the field of RDs, were included in Additional file 3. Articles were selected and referenced in the review if they if they contributed to the discussion and conclusions drawn by the ECRIN expert panel, and included valid considerations on how barriers to the conduct of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) on RDs could affect their number, feasibility, and quality. The results are described narratively, which is a limitation of the data collected.

Results and discussion

Search results

The systematic searches identified a total of 148 references. The screening process narrowed the academic literature search down to 37 relevant references listed in Additional file 3. Characteristics of included references: overviews and narrative reviews.

Main barriers related to clinical trials for rare diseases

Recruitment issues: a direct consequence from rarity

Clinical trials on RDs are characterised by an intrinsic difficulty to identify patients. This problem resides in the difficulty to diagnose RDs, to record diseases, and to trace RD patients [28]. This is due in part to the scarce knowledge about these diseases, and to the fact that far from all countries have efficient processes for referral [29], resulting in significant delays in diagnosis. RD patients often remain undiagnosed even in the best conditions of expertise due to lack of knowledge about natural history or clinical signs and symptoms. However, the most recent technological developments such as lower-cost, next-generation gene sequencing is increasing the diagnostic capacity for monogenic diseases, thereby contributing to increased knowledge of potentially actionable ethiopathogenic mechanisms [30].

In all cases, RDs are poorly represented in medical nomenclatures used in health information systems [28], making it difficult to identify participants for clinical research from medical records. Most countries use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) to record patients, where around 500 RDs have a specific code [31]. In countries using Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED), the situation is not much better because only around 40% of RDs are listed here (Ana Rath, personal communication on the Orphanet-SNOMED CT mapping exercise, August 2015).

Another source for identification of RD patients is disease-specific patient registries. There are 690 such registries in Europe, covering 984 RDs [32]. Most are national (482 registries), or regional (75 registries), with some being European (59 registries) or international (74 registries). However, quality, scope, and capacity of many registries are limited [28].

The geographical dispersion of patients requires multicentric, multinational collaboration, introducing additional regulatory and funding barriers. For severe RDs, travel to research centres may pose an insurmountable barrier to research participation. Solutions include the leveraging of technology to monitor patients remotely, and setting up community centres to better deliver these trials to patients who otherwise would be unable to access them [33]. Effective recruitment is also supported through partnership with patient organisations when they exist, but also with patient registries and centres of expertise.

These barriers hamper recruitment into clinical trials. In Europe, a voluntary policy has been undertaken in order to improve diagnostic rates, i.e. by enhancing the expertise of specialised centres, and to establish European Reference Networks (ERNs) expected to spread expertise and share best practice. ERNs are expected to catalyse the international cooperation and patient engagement needed for clinical research. In parallel, in order to increase the visibility of RD patients in health information systems, a specific standard nomenclature for RDs – the Orphanet nomenclature [34] – is promoted in the European member states [35]. The implementation of the Orphanet nomenclature of RDs (the Orphacode) which is linked to other nomenclatures and resources used both in the clinical setting (ICD-10, SNOMED Clinical Terms) and in the research setting (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM); Human Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC); Universal Protein Resource (UniProtKB); among others [31]) will make it possible to more easily identify patients from health records for clinical research. The Orphanet nomenclature should also enable data exploitation with the aim of improving knowledge of the natural history of RDs.

Limited knowledge on natural history of rare diseases

The natural history of most RDs is often difficult to document, yet it is a necessary step to inform to the trial design for the disease. Few relevant epidemiological studies are published due to the difficulty of identifying and documenting patients widely spread geographically, not always diagnosed properly, and rarely followed-up by academic centres in a systematic way. Most attempts to collect good quality data are supported by short-term grants, which do not allow continuity in the effort. The high cost of high-quality natural history studies has been a significant obstacle to their conduct. This is well identified as a barrier requiring solutions and has been the target of recommendations of the EU Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases (Commission Expert Groups on Rare Diseases (CEGRD), formerly EUCERD) [36] and of the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium [37]. The lack of natural history information provides little insight into how to choose outcomes or how to design and power a clinical trial. When disease-specific registries meet quality standards, their relevance for contributing to high-quality clinical trials is demonstrated [38]. Structure and design of natural history studies are pivotal to capture clinical information efficiently in order to be used in safety and efficacy determination. Knowledge of natural history is one of the first crucial steps for building evidence as it allows for a better choice of clinically relevant outcomes as well as of the duration needed to monitor for them to occur [33]. There is a need to capture clinical information more cost-efficiently and to help inform the optimal approach to treatment development. Data collection in the framework of European Reference Networks should be encouraged and facilitated by common interoperability standards and tools to address this issue.

Need for trial designs adapted to the small population size and clinical heterogeneity

RCTs are the goal standard for producing evidence on the efficacy of an intervention because they have a strong internal validity by minimising bias and confounder factors [1, 39]. Systematic reviews of RCTs provide the highest level of evidence assessing the benefits and harms of interventions [1]. However, randomisation can prove to be difficult with RDs, mostly because of the small size of the patient population.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA), in a guideline on trials in RD populations, stated that there are no methods relevant for small trials that are not also applicable to large studies [40]. The problem for trials in RD populations is that the reverse would lead to requests for sample sizes that are not practicable, or simply impossible to reach.

The traditional RCT designs are difficult to conduct in small populations because it is very difficult to create homogeneous groups and to adequately assess changes between variable groups. Alternative methods have been proposed and could be applicable under certain conditions. We will briefly discuss some of them here. For in-depth analyses and comparisons between some of these different trial designs, see references [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,57].

The traditional fixed error rates (alpha = 0.05; beta = 0.20) cannot capture all desirable inferences in different clinical research settings. Therefore, Ioannidis and colleagues have developed models that optimise the selection of type I and type II errors according to available sample size and a plausible intervention effect [50].

Controlled rigorous designs that allow within-patient comparisons and treat all participants would assess therapies more accurately if feasible. Such study designs comprise n-of-1 designs and crossover trials. Both assess efficacy of a treatment based on short-term outcomes and mitigate the effects of clinical heterogeneity in a patient population [39, 40].

Pragmatic RCTs could represent an alternative to early phase RCTs while keeping most of their methodological advantages. These pragmatic trials are intended to inform decisions in common practice, so eligibility criteria are more inclusive, comparisons are done against standards of care instead of placebo, and follow-up tends to evaluate longer-term effects than early phase RCTs [39].

Vickers and Scardino and Potter et al. argue for a wide adoption of what they call ‘clinically integrated’ or ‘hybrid design’ RCTs [39, 51]. These trials incorporate aspects of observational and interventional trials (for instance, cohort multiple randomised controlled trials – cmRCTs), thus allowing for a more efficient knowledge transfer into real-world clinical practice. The designs promote longitudinal observational data collection (registries and cohorts). Such investment would be, in our view, the most efficient use of resources in the long term, as it allows for a better understanding of diseases and for the assessment of different interventions over time in a controlled way while knowledge progresses.

Other study designs more focused on proving the efficacy of interventions, more often drugs that are expected to transform the disease course, include adaptive designs. Response-adaptive methods change allocation ratios depending on which treatment appears to be best. Adaptive methods are defined by the EMA as a ‘statistical methodology (that) allows the modification of a design element (e.g. sample size, randomisation ratio, number of treatment arms) at an interim analysis with full control of type I error’ [52]. Adaptive trials are complex and need even stronger measures to prevent biasing adaptive decisions in the course of the trial [53]. Mauer and EORTC collaborators, for instance, point out the fact that regulatory and financial management need to be adaptive as well, so such trials increase the organisational and economical burdens [50]. Adaptive methods rely on real-time data, which may be easier in RD trials because recruitment tends to be slower. Some adaptive designs are now used for rare cancers [53]. Other sequential adaptive methods are proposed for testing different therapeutic possibilities in a small population [54, 55]. Regulators accept or recommend some of these designs [56]. For an in extenso review of the different designs available and their acceptance by regulatory bodies (FDA, EMA) please see Billingham et al. [57].

The RD field needs the development of cost-efficient, novel, rigorous controlled trial designs and relevant analyses that are effective in studying efficacy in heterogeneous, small populations. Recently, the European Commission funded three projects in this area [58,59,60]. In addition, the IRDiRC consortium has established a task force to address the question and produce recommendations [61].

As for any other disease, the laws of probability and statistics apply to RDs. Therefore, valid evidence on interventions requires valid clinical research in the form of large, well-conducted RCTs [1, 7, 39, 45].

Organisational challenges: a consequence from the need for multinational randomised clinical trials

Patients with most RDs are not so few as to prevent conducting large RCTs. In the EU, a prevalence of 1/100,000 with a RD (i.e. well below the threshold of 5/10,000) results in an availability of 5000 potential trial participants [62]. It requires, however, multinational cooperation, which introduces a new line of barriers in the form of comprehensive organisational, regulatory, and economical requirements. The identification of partners having both the expertise and the capacity to conduct international RCTs, the organisation of the collaboration, and also of the monitoring and follow-up are challenging. The collection and maintenance of high-quality data among all parties involved is a major issue, and specific measures should be put in place to ensure the best, easy-to-use quality. These challenges are greater in RDs, as they often need a multi-disciplinary management team as well as professionals from diverse hospital departments, which makes monitoring and organisation more complex.

Different legal frameworks in different countries contribute to the regulatory barriers of conducting multicentre international RCTs. Heterogeneity can involve all the following: ethics committee submission, patient information and consent, insurance acquisition, activation of the clinical centre, data protection rules, and investigator reimbursement. The need for harmonised procedures has been addressed by setting the Voluntary Harmonisation Procedure (VHP) in the European Union in order to organise the assessment of multinational RCTs, which is the responsibility of the Clinical Trials Facilitation Group of the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) [63]. From 2009 to 2015, 22% of European clinical trials underwent that procedure, the numbers having increased impressively over time [64]. When the European clinical trials regulation is implemented in 2018 [65], the need for VHP is expected to decrease or completely disappear.

Need for more sensitive outcomes to quantify clinical benefit

Maybe more than in other fields, RDs are often characterised by important clinical variability, including age of onset, severity, speed of evolution, responsiveness to treatment, global impact in health status, and functional consequences. This situation leads to a very large range at baseline for many measures of efficacy, making it hard to detect important changes of an intervention. In fact, traditional RCTs assess average treatment impact in selected patients, and thus do not accommodate clinical heterogeneity very well [39]. Researchers often use surrogate outcomes to measure the effects of an intervention [66]. Such surrogates must be correlated to a clinically meaningful outcome. However, correlation alone does not make a surrogate valid [66]. Intensive analyses linking the intervention effect on the surrogate to patient-centred outcomes are needed [66,67,68,69]. Biomarker development is one source for potential surrogate outcomes. FDA and EMA orphan drug regulations contemplate approval of drugs for which the benefits for patients with unmet medical needs are based on reasonable evidence, often based on surrogate outcomes, that should demonstrate their clinical benefit during post-marketed studies [29]. Such ‘adaptive’ pathways and procedures seem to have their special problems making them less attractive or outright dangerous to patients [21, 70]. Drug or medical device companies could base their marketing authorisation applications on uncontrolled or controlled observational studies rather than pivotal RCTs. Such applications could lead to marketing approval of interventions that are without effect or that are even harmful. Such interventions are difficult or impossible to remove from the market.

However, both patients and decision-makers will seek more patient-centred, clinically relevant benefits [39]. These patient-centred outcomes can be reported by clinicians (clinician-reported outcome measures) or other observers (observer-reported outcome measures), or by the patients themselves (patient-reported outcome measures, PROM) [71].

On the other hand, the frequent complexity of disease manifestations in multiple body systems may require more than one clinical outcome for one domain to adequately assess a clinically effective treatment. That puts extra burden on the statistical assessment of outcomes [72]. As single clinical outcomes may not adequately cover the multiple expression of a disease, novel approaches to combine independent clinical outcomes in multi-domain analyses could potentially help assessing the clinical efficacy of an intervention. However, such analyses are statistically complex, the weight of each clinical variable could not be adequately measured, and results could be difficult to compare from trial to trial [73]. Nevertheless, the development of multiple domain outcome strategies in smaller populations offers important advantages over single primary outcomes [74]. Well-chosen and designed multiple domain outcomes would capture broader therapeutic data, provide greater insight into overall treatment effects, and allow successful small trials with compelling new treatments when the benefit might be varying between individual patients.

The development of agreed standardised sets of outcomes, the core outcome sets (COS) would result in better comparability between clinical studies, by defining the minimum outcomes that should be assessed when evaluating a new intervention. Initiatives like COMET develop both COS and a consensus core outcome sets database in which several RDs are represented [75]. A task force on patient-centred outcome measures have been set up by the IRDiRC, and a first overview and recommendations document has been open to public consultation [67]. The landscape of initiatives on the matter, including those concerning RDs, is depicted [71]. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR)[76] has set up a task force on Rare Disease Trials Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) measurement [77]. This task force aims to provide recommendations on the development of patient-centred outcome measures (PCOMs) in conformity to the regulatory guidance for the evaluation and proof of treatment benefits for medicinal products approval. The recent recommendations of the ISPOR Pediatric PRO Task Force [78] provide good research practices in developing and implementing paediatric patient-reported outcomes instruments and, therefore, is of interest for RDs, because most of them are paediatric.

Understanding the clinical meaningfulness of clinical changes in a patient is difficult without significant prior clinical experience. A systematic approach using natural history and comparable disease information has to be developed. The construction of the future evidence starts by the collection of natural history data in a systematic way (registries, cohorts) and by the capture of data from clinical records in a structured way. Patient engagement should be sought and encouraged from this early stage.

Need for involvement of all the stakeholders in the study design and conduct

The design and specific methodological aspects of a clinical trial need to be carefully discussed with all relevant partners. As stated in Potter et al. [39] ‘ideally, evaluative research should incorporate outcomes that are of greatest importance with respect to treatment goals, based on a consensus among patients, clinical providers, researchers, and policy decision-makers’. The final goal is to translate knowledge into clinical practice, based on the best evidence. Doing this requires effective interaction among stakeholders from the earliest phase, i.e. data collection to increase the knowledge of each RD. Thus, databases and registries should incorporate patients’ views. Some experiences exist already in which patients contribute directly to data collection [79].

Usually, a significant proportion of those with an RD must be enrolled in trials to reach the required sample size. The relationship between the clinician and the patient needs to be based on mutual trust for the patients to agree to take part and once in the trial, to stay in and provide outcome data. These data must answer a question that is important for patients, clinicians, and policy-makers, and data must be collected in such a way that taking part in the trial leaves a participant willing to take part in more.

A trial involving a RD population must, in short, be compellingly efficient and involve all stakeholders, especially patients, in its design. The regulators as well should be included in the discussion about the most appropriate design for a specific trial, as early as possible in the research process. Protocol assistance and scientific advice from regulatory bodies have been shown to play a key role in guiding the conduct of studies to address the benefit/risk analysis for marketing authorisation and approval [80]. However, the scientific advice provided by regulatory authorities poses serious concerns about conflict of interests as it is delivered by the very same agency that will grant the marketing approval at a later time point.

Centres with expertise in RDs should play a major role in fostering clinical research networks and infrastructures and in disseminating and sharing study outcomes. Training of investigators and patients’ representatives will ensure a better understanding of regulatory, methodological, and ethical requirements. The development of European reference networks in the coming months offers an opportunity to put this statement into practice. In addition, support from organisations, such as ECRIN, can greatly enhance the organisation and management of multinational clinical trials on RDs. In effect, ECRIN brings together national networks of clinical trial units across Europe, making it possible to accelerate patient recruitment and trial implementation, while ensuring the appropriate management services for smooth trial conduct. By using ECRIN (or a similar infrastructure), there is an opportunity to develop common and harmonised practices for the submission, monitoring and reporting of multicentre and multinational RD clinical trials.

Conclusions

The main barriers described above for conducting RCTs in RD patients should be seen as additions to the barriers facing all clinical trials: inadequate knowledge and understanding of clinical research and trial methodology; lack of funding; excessive monitoring; restrictive interpretation of privacy law and lack of transparency; overly complex or inadequate regulatory requirements; and inadequate clinical research infrastructures [25].

The area of RDs is in particular need of a concerted approach of all interested parties as the challenges due to rarity are especially complex. There is a need for solid evidence before offering innovative treatments to patients [73]. The difficulties can only be overcome if a multi-stakeholder dialogue is going on, which is the recommendation of the EUCERD [81] and ICORD [82]. This multi-stakeholder approach is needed from the earliest stages of the construction of evidence, before any clinical research is commenced. Data production and collection in a way they can be shared, exploited, and re-used is a key issue to increase the knowledge of the natural history of each RD, thus identifying clinically relevant indicators for patient-centred care based on evidence [83]. Identification of optimal future outcomes is mandatory when designing future trials. Simulations may help to decide on the most appropriate study design [84]. Patient registries or systematic collections should take into consideration the views of patients. The establishment of multicentre databases/registries in a structured way, taking into account the requirements of high-quality clinical research and of regulatory exigencies, is mandatory to achieve good-quality clinical research [85]. The future European reference networks could provide a timely opportunity to work this way with the aim to conduct clinical ‘research done differently’ [86], meaning clinical effectiveness research (CER) with a clear focus on including stakeholders in the planning activities. They should also be the place for implementing educational training on clinical research for clinicians which is an already identified limitation in the conduct of multicentric RCTs [87].

However, clinical research for RDs poses specific problems that need to be addressed, and they have been roughly summarised in this paper. Multinational RCTs are needed in order to increase the size of the population studied despite the fact that this may create organisational, monitoring, and regulatory burdens. Tools and support provided by ECRIN are aimed to help overcome these barriers. Several multinational RCTs on RDs are already being conducted with the support of ECRIN [24].

If the data originate from small populations, there are special problems when two or more RCTs should be meta-analysed [88]. In these situations, special analytic methods need to be considered [88]. In these situations, using frequentist methods, it is also important to assess data with Trial Sequential Analysis to control random type I and type II errors due to sparse data and repetitive testing [1, 89, 90]. For a given required information size, a corresponding number of required trials exist. By increasing the number of trials, one can increase the power of a random-effects model meta-analysis [91].

Addressing the specific problems posed by RD clinical research is of paramount importance to provide best practice medical management to these patients. Improvements of the methodologies used for establishing evidence-based clinical practice within RD will also benefit clinical research on ‘personalised medicine’ for more common diseases. We need to make published clinical research become more valid, and to get all clinical research published, including research with negative results [1, 83, 92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

Notes

Funded by the European Union Framework Programme 7 (EU FP7; grant agreement no. 284395), ECRIN-IA involved 23 countries and brought together diverse stakeholders to overcome barriers to clinical research in three particularly difficult areas (rare diseases, medical devices, and nutrition). Specifically, the project aimed to develop tools, services, and infrastructure to facilitate multinational clinical research in Europe, and to support the development of pan-European disease networks to drive clinical projects. This in turn was intended to improve Europe’s attractiveness to industry, boost its scientific competitiveness, and result in better healthcare for European citizens. Originally planned for 4 years (2012 to 2015), the clinical trials work package was extended until 2017.

Abbreviations

- CDSR:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- CEGRD:

-

Commission Expert Groups on Rare Diseases

- CER:

-

Clinical effectiveness research

- cmRCT:

-

Cohort multiple randomised controlled trial

- COA:

-

Clinical outcome assessment

- COMET:

-

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials

- COS:

-

Core outcome sets

- DARE:

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

- ECRIN:

-

European Clinical Infrastructure Network

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- EORTC:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- EUCERD:

-

European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- HGNC:

-

Human Gene Nomenclature Committee

- HMA:

-

Head of Medicines Agencies

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- ICORD:

-

International Conference on Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs

- IRDiRC:

-

International Rare Diseases Research Consortium

- ISPOR:

-

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research

- NHSEED:

-

National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database

- OMIM:

-

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- PCOM:

-

Patient-centred outcome measures

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcomes

- PROM:

-

Patient-reported outcome measures

- RCT:

-

Randomised clinical trial

- RD:

-

Rare diseases

- SNOMED:

-

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine

- UniProtKB:

-

Universal Protein Resource

- VHP:

-

Voluntary Harmonisation Procedure

References

Garattini S, Jakobsen JC, Wetterslev J, Bertele V, Banzi R, Rath A, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice: overview of threats to the validity of evidence and how to minimise them. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;32:13–21. Epub 11 May 2016.

Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 of The European Parliament and of The Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. 2000. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2000:018:0001:0005:en:PDF.

Song P, Gao J, Inagaki Y, Kokudo N, Tang W. Rare diseases, orphan drugs, and their regulation in Asia: current status and future perspectives. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2012;1(1):3–9. Epub 1 Feb 2012.

National Institute of Health. Public Law 107–280 107th Congress. Rare Diseases Act. 2002. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/PL107-280.pdf.

Rath AM, Nguengang Wakap S. Orphanet Report Series - Prevalence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data, Number 1. 2017. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf.

Orphanet. 2017 [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/index.php.

Schlander M, Garattini S, Holm S, Kolominsky-Rabas P, Nord E, Persson U, et al. Incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year gained? The need for alternative methods to evaluate medical interventions for ultra-rare disorders. J Comp Effectiveness Res. 2014;3(4):399–422. Epub 3 Oct 2014.

Bell SA, Tudur Smith C. A comparison of interventional clinical trials in rare versus non-rare diseases: an analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:170. Epub 28 Nov 2014.

European Union. Council Recommendation of 8 June 2009 on an action in the field of rare diseases. 2009. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2009:151:0007:0010:EN:PDF.

Aymé S, Rodwell C. European Committee Expert Group on Rare Diseases. Report on the State of the Art of Rare Disease Activities in Europe. 2014. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.eucerd.eu/?page_id=15.

Commission Of The European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions on Rare Diseases: Europe’s challenge 2008. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/non_com/docs/rare_com_en.pdf.

European Commission. Implementation Report on the Commission Communication on Rare Diseases: Europe’s challenges and council recommendation of 8 June 2009 on an action in the field of rare diseases. 2009. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/rare_diseases/docs/2014_rarediseases_implementationreport_en.pdf.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Regulations. Title 21: Food and Drugs. PART 316—ORPHAN DRUGS. 2015. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=316&showFR=1.

International Rare Diseases Research Consortium. About. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.irdirc.org/.

Rath AM, Salamon V. Orphanet Report Series - Lists of medicinal products for rare diseases in Europe. 2017. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/list_of_orphan_drugs_in_europe.pdf.

Food and Drug Administration. Rare Disease and Orphan Drug Designated Approvals. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/drugandbiologicapprovalreports/ndaandblaapprovalreports/ucm373419.htm.

Joppi R, Bertele V, Garattini S. Orphan drugs, orphan diseases. The first decade of orphan drug legislation in the EU. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4):1009–24. Epub 24 Oct 2012.

Westermark K, Holm BB, Soderholm M, Llinares-Garcia J, Riviere F, Aarum S, et al. European regulation on orphan medicinal products: 10 years of experience and future perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(5):341–9. Epub 3 May 2011.

Food and Drug Administration. Novel Drugs Summary. 2015. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugInnovation/ucm474696.htm.

European Medicines Agency. Latest news. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/.

Davis C, Lexchin J, Jefferson T, Gotzsche P, McKee M. ‘Adaptive pathways’ to drug authorisation: adapting to industry? BMJ. 2016;354:i4437. Epub 18 Aug 2016.

Health Action International, The International Society of Drug Bulletins, The Medicines in Europe Forum, The Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Centre TNC. Joint Briefing Paper. ‘Adaptive licensing’ or ‘adaptive pathways’: Deregulation under the guise of earlier access. Brussels. 2015. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.isdbweb.org/en/publications/view/adaptive-licensing-or-adaptive-pathways-deregulation-under-the-guise-of-earlier-access.

Eichler HG, Oye K, Baird LG, Abadie E, Brown J, Drum CL, et al. Adaptive licensing: taking the next step in the evolution of drug approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):426–37. Epub 18 Feb 2012.

Demotes-Mainard J, Kubiak C. A European perspective—the European clinical research infrastructures network. Ann Oncol. 2011;22 Suppl 7:vii44–9. Epub 9 Nov 2011.

Djurisic S, Rath A, Gaber S, Garattini S, Bertele V, Ngwabyt SN, et al. Barriers to the conduct of randomised clinical trials within all disease areas. Trials. 2017;18(1):360.

Laville M, Segrestin B, Masson Y, Ruano-Rodríguez C, Serra-Majem L, Hyesmaye M, et al. Evidence-based practice within nutrition: what are the barriers for improving the evidence and how can they be dealt with? Trials. 2017;18(1):425.

Neugebauer EAM, Rath A, Antoine S-L, Eikermann M, Seidel D, Koenen C, et al. Specific barriers to the conduct of randomised clinical trials on medical devices. Trials. 2017;18(1):427.

Valdez R, Ouyang L, Bolen J. Public health and rare diseases: oxymoron no more. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E05. Epub 15 Jan 2016.

Shash E, Negrouk A, Marreaud S, Golfinopoulos V, Lacombe D, Meunier F. International clinical trials setting for rare cancers: organisational and regulatory constraints-the EORTC perspective. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:321. Epub 30 May 2013.

Boycott KM, Vanstone MR, Bulman DE, MacKenzie AE. Rare-disease genetics in the era of next-generation sequencing: discovery to translation. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(10):681–91. Epub 4 Sep 2013.

Orphanet. Orphadata. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.orphadata.org/cgi-bin/inc/product1.inc.php.

Rath AM, Peixoto S. Disease registries in Europe. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Registries.pdf.

Augustine EF, Adams HR, Mink JW. Clinical trials in rare disease: challenges and opportunities. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(9):1142–50. Epub 10 Sep 2013.

Rath A, Olry A, Dhombres F, Brandt MM, Urbero B, Ayme S. Representation of rare diseases in health information systems: the Orphanet approach to serve a wide range of end users. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(5):803–8. Epub 17 Mar 2012.

Commission Expert Group for Rare Diseases. Recommendation on ways to improve codification for rare diseases. 2014. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/rare_diseases/docs/recommendation_coding_cegrd_en.pdf.

European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases. EUCERD core recommendations on rare disease patient registration and data collection to the European Commission, Member States and all stakeholders. 2013. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.eucerd.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/EUCERD_Recommendations_RDRegistryDataCollection_adopted.pdf.

International Rare Diseases Research Consortium. Policies and guidelines. 2013. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.irdirc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/IRDiRC_policies_24MayApr2013.pdf.

Rodger S, Lochmuller H, Tassoni A, Gramsch K, Konig K, Bushby K, et al. The TREAT-NMD care and trial site registry: an online registry to facilitate clinical research for neuromuscular diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:171. Epub 24 Oct 2013.

Potter BK, Khangura SD, Tingley K, Chakraborty P, Little J. Translating rare-disease therapies into improved care for patients and families: what are the right outcomes, designs, and engagement approaches in health-systems research? Genet Med. 2016;18(2):117–23. Epub 10 Apr 2015.

Tudur Smith C, Williamson PR, Beresford MW. Methodology of clinical trials for rare diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(2):247–62. Epub 30 Jun 2014.

Gupta S, Faughnan ME, Tomlinson GA, Bayoumi AM. A framework for applying unfamiliar trial designs in studies of rare diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(10):1085–94. Epub 3 May 2011.

Korn EL, McShane LM, Freidlin B. Statistical challenges in the evaluation of treatments for small patient populations. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(178):178sr3. Epub 29 Mar 2013.

Cornu C, Kassai B, Fisch R, Chiron C, Alberti C, Guerrini R, et al. Experimental designs for small randomised clinical trials: an algorithm for choice. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:48. Epub 28 Mar 2013.

Gagne JJ, Thompson L, O’Keefe K, Kesselheim AS. Innovative research methods for studying treatments for rare diseases: methodological review. BMJ. 2014;349:g6802. Epub 26 Nov 2014.

Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ES, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(5):365–76. Epub 11 Apr 2013.

Parmar MK, Sydes MR, Morris TP. How do you design randomised trials for smaller populations? A framework. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):183. Epub 26 Nov 2016.

Hilgers RD, Roes K, Stallard N. Directions for new developments on statistical design and analysis of small population group trials. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):78. Epub 16 Jun 2016.

Roes KC. A framework: make it useful to guide and improve practice of clinical trial design in smaller populations. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):195. Epub 26 Nov 2016.

Nikolakopoulos S, Roes KC, van der Tweel I. Sequential designs with small samples: evaluation and recommendations for normal responses. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016. Epub 28 Jun 2016.

Ioannidis JP, Hozo I, Djulbegovic B. Optimal type I and type II error pairs when the available sample size is fixed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8):903–10. e2 Epub 15 May 2013.

Vickers AJ, Scardino PT. The clinically-integrated randomized trial: proposed novel method for conducting large trials at low cost. Trials. 2009;10:14. Epub 7 Mar 2009.

European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on methodological issues in confirmatory clinical trials planned with an adaptive design. 2007. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003616.pdf.

Mauer M, Collette L, Bogaerts J. Adaptive designs at European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) with a focus on adaptive sample size re-estimation based on interim-effect size. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(9):1386–91. Epub 28 Jan 2012.

Tamura RN, Krischer JP, Pagnoux C, Micheletti R, Grayson PC, Chen YF, et al. A small n sequential multiple assignment randomized trial design for use in rare disease research. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;46:48–51. Epub 21 Nov 2015.

Hlavin G, Koenig F, Male C, Posch M, Bauer P. Evidence, eminence and extrapolation. Stat Med. 2016;35(13):2117–32. Epub 13 Jan 2016.

Guideline on clinical trials in small populations. Doc. Ref. CHMP/EWP/83561/2005, 2006. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003615.pdf.

Billingham L, Malottki K, Steven N. Research methods to change clinical practice for patients with rare cancers. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):e70–80. Epub 13 Feb 2016.

Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen University. Integrated DEsign and AnaLysis of small population group trials (IDEAL). 2013. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.rwth-aachen.de/go/id/ehgl/?lidx=1.

Warwick Medical School. Innovative methodology for small populations research (INSPIRE). 2016. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/hscience/stats/currentprojects/inspire/.

Community Research and Development Information Service. Advances in Small Trials dEsign for Regulatory Innovation and eXcellence (ASTERIX). 2016. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://cordis.europa.eu/projects/rcn/110076_en.html.

International Rare Diseases Research Consortium. International Rare Diseases Research Consortium’s Task Force on Small Population Clinical Trials. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.irdirc.org/activities/current-activities/tf-spct/.

Joppi R, Bertele V, Garattini S. Orphan drug development is not taking off. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(5):494–502. Epub 26 Jun 2009.

Heads of Medicines Agencies. Clinical trials facilitation group. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.hma.eu/ctfg.html.

Heads of Medicines Agencies. Metrics on participation of National Competent Authorities. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14); Available from: http://www.hma.eu/fileadmin/dateien/Human_Medicines/01-About_HMA/Working_Groups/CTFG/2016_05_CTFG_Metrics_on_NCA_participation_Jan15_Jan16.pdf.

European Medicines Agency. Updates. 2017. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000629.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05808768df.

Gluud C, Brok J, Gong Y, Koretz RL. Hepatology may have problems with putative surrogate outcome measures. J Hepatol. 2007;46(4):734–42. Epub 24 Feb 2007.

Molenberghs G, Geys H, Buyse M. Evaluation of surrogate endpoints in randomized experiments with mixed discrete and continuous outcomes. Stat Med. 2001;20(20):3023–38. Epub 9 Oct 2001.

Molenberghs G, Burzykowski T, Alonso A, Assam P, Tilahun A, Buyse M. A unified framework for the evaluation of surrogate endpoints in mental-health clinical trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19(3):205–36. Epub 18 Jul 2009.

Ensor H, Lee RJ, Sudlow C, Weir CJ. Statistical approaches for evaluating surrogate outcomes in clinical trials: a systematic review. J Biopharm Stat. 2015:1–21. Epub 24 Sep 2015.

Joppi R, Gerardi C, Bertele V, Garattini S. Letting post-marketing bridge the evidence gap: the case of orphan drugs. BMJ. 2016;353:i2978. Epub 24 Jun 2016.

International Rare Diseases Research Consortium. Patient-centered outcome measures initiatives in the field of rare diseases. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.irdirc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/PCOM_Post-Workshop_Report_Final.pdf.

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Winkel P, Lange T, Wetterslev J. The thresholds for statistical and clinical significance—a five-step procedure for evaluation of intervention effects in randomised clinical trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:34. Epub 5 Mar 2014.

Perea-Milla E, Aycaguer LC, Cerda JC, Saiz FG, Rivas-Ruiz F, Danet A, et al. Efficacy of prescribed injectable diacetylmorphine in the Andalusian trial: Bayesian analysis of responders and non-responders according to a multi domain outcome index. Trials. 2009;10:70. Epub 18 Aug 2009.

Putzeist M, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Wied CC, Hoes AW, Leufkens HG, de Vrueh RL. Drug development for exceptionally rare metabolic diseases: challenging but not impossible. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:179. Epub 19 Nov 2013.

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials Initiative. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET). 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org.

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. About. 2017. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.ispor.org.

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) in Rare Disease Clinical Trials—Emerging Good Practices: Report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Trials COA Measurement Task Force. 2016. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.ispor.org/TaskForces/ClinicalOutcomesAssessment-RareDisease-ClinicalTrials.asp.

Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health. 2013;16(4):461–79. Epub 26 Jun 2013.

LEUKOTREAT. Therapeutic strategies for leukodystrophy affected patients. LeukoDataBase & Ethics. 2015. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.leukotreat.eu/leukodatabase-ethics.php.

Tafuri G, Pagnini M, Moseley J, Massari M, Petavy F, Behring A, et al. How aligned are the perspectives of EU regulators and HTA bodies? A comparative analysis of regulatory-HTA parallel scientific advice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(4):965–73. Epub 2 Jun 2016.

European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases. Recommendation to the European Commission and Member States on improving informed decisions based on the clinical added value of orphan medicinal products information flow. 2012. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.eucerd.eu/?post_type=document&p=1446.

Forman J, Taruscio D, Llera VA, Barrera LA, Cote TR, Edfjall C, et al. The need for worldwide policy and action plans for rare diseases. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(8):805–7. Epub 24 Apr 2012.

Skoog M, Saarimäki JM, Gluud C, Sheinin M, Erlendsson K, Aamdal S. Transparency and registration in clinical research in the Nordic countries (Report). Nordic Trial Alliance, NordForsk. Oslo. Norge. 2015:1–108. (cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://nta.nordforsk.org/projects/nta_transparency_report.pdf.

Bajard A, Chabaud S, Cornu C, Castellan AC, Malik S, Kurbatova P, et al. An in silico approach helped to identify the best experimental design, population, and outcome for future randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:125–36. Epub 19 Jul 2015.

Bolignano D, Pisano A. Good-quality research in rare diseases: trials and tribulations. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31:217-23. Epub 29 Jan 2016.

Patient-Centered Outcome Measures Research Institute. About. 2017. [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.pcori.org/about-us.

Ahmed R, Duerr U, Gavenis K, Hilgers R, Gross O. Challenges for academic investigator-initiated pediatric trials for rare diseases. Clin Ther. 2014;36(2):184–90. Epub 18 Feb 2014.

Friede T, Rover C, Wandel S, Neuenschwander B. Meta-analysis of few small studies in orphan diseases. Res Synth Methods. 2016;8:79-91. Epub 30 Jun 2016.

Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):64–75. Epub 18 Dec 2007.

Imberger G, Thorlund K, Gluud C, Wetterslev J. False-positive findings in Cochrane meta-analyses with and without application of trial sequential analysis: an empirical review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e011890. Epub 16 Aug 2016.

Kulinskaya E, Wood J. Trial sequential methods for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(3):212–20. Epub 9 Jun 2015.

Ioannidis JP. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001747. Epub 22 Oct 2014.

Alberts B, Kirschner MW, Tilghman S, Varmus H. Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(16):5773–7. Epub 16 Apr 2014.

Ioannidis JP, Fanelli D, Dunne DD, Goodman SN. Meta-research: evaluation and improvement of research methods and practices. PLoS Biol. 2015;13(10):e1002264. Epub 3 Oct 2015.

Gotzsche PC. Blinding during data analysis and writing of manuscripts. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(4):285–90. discussion 90–3 Epub 1 Aug 1996.

MacCoun R, Perlmutter S. Blind analysis: hide results to seek the truth. Nature. 2015;526(7572):187–9. Epub 10 Oct 2015.

The Academy of Medical Sciences Medical Research Council. Symposium Report. Reproducibility and reliability of biomedical research: improving research practice. Welcome Trust. 2015 [cited 2017 November 14]; Available from: http://www.acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/reproducibility-and-reliability-of-biomedical-research/.

Jarvinen TL, Sihvonen R, Bhandari M, Sprague S, Malmivaara A, Paavola M, et al. Blinded interpretation of study results can feasibly and effectively diminish interpretation bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(7):769–72. Epub 25 Feb 2014.

Acknowledgements

The EU FP7 grant supporting the ECRIN-IA (GA 284395) provided support for meetings and is acknowledged for making the present paper possible. The Mario Negri Institute is thanked for housing the ECRIN-IA meeting in February 2013. All participants of ECRIN-IA are acknowledged for participating in discussions identifying the barriers and threats to the conduct of RCTs. Sarah Louise Klingenberg, the Trial Search Coordinator of The Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group at The Copenhagen Trial Unit, is thanked for conducting the academic literature searches.

Funding

The present review is founded by the European Commission through a grant awarded for the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network-Integrated Activity project. Project reference: 284395. Funded under: FP7-INFRASTRUCTURES. The funding sources had no influence on data collection, design, analysis, interpretation, or any aspect pertinent to the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR, SD, and CG drafted the manuscript. SD and CG performed systematic literature searches and selected the papers. VS, SP, VH, ML, BS, EAMN, ME, VB, SG, JW, RB, JCJ, CK, and JD critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to all the data (including PDFs of the articles and the search results) and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors are involved in the ECRIN-IA project. AR, VS, SP, and VH work at Orphanet, a reference portal for information on rare diseases and orphan drugs for all audiences. Orphanet’s aim is to help improve the diagnosis, care, and treatment of patients with rare diseases. No additional conflicts are known.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Academic literature search strategy. Exact search strategy applied for analyses. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 63 kb)

Additional file 3:

Relevant references from academic literature search. Results listed from literature search in the form of relevant publications. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rath, A., Salamon, V., Peixoto, S. et al. A systematic literature review of evidence-based clinical practice for rare diseases: what are the perceived and real barriers for improving the evidence and how can they be overcome?. Trials 18, 556 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2287-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2287-7