Abstract

Background

Accreditation is used increasingly in health systems worldwide. However, there is a lack of evidence on the effects of accreditation, particularly in general practice. In 2016 a mandatory accreditation scheme was initiated in Denmark, and during a 3-year period all practices, as default, should undergo accreditation according to the Danish Healthcare Quality Program. The aim of this study is primarily to evaluate the effects of a mandatory accreditation scheme.

Methods/design

The study is conducted as a cluster-randomized controlled trial among 1252 practices (clusters) with 2211 general practitioners in Denmark. Practices allocated to accreditation in 2016 serve as the intervention group, and practices allocated to accreditation in 2018 serve as controls. The selected outcomes should meet the following criteria: (1) a high degree of clinical relevance; (2) the possibility to assess changes due to accreditation; (3) availability of data from registers with no self-reporting data. The primary outcome is the number of prescribed drugs in patients older than 65 years. Secondary outcomes are changes in outcomes related to other perspectives of safe medication, good clinical practice and mortality. All outcomes relate to quality indicators included in the Danish Healthcare Quality Program, which is based on general principles for accreditation.

Discussion

The consequences of accreditation and standard-setting processes are generally under-researched, particularly in general practice. This is the largest study in general practice with a randomized implementation approach to evaluate the clinical effects of a nation-wide mandatory accreditation scheme in general practice.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02762240. Registered on 24 May 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Accreditation is a procedure in which a recognized external institution evaluates an organization on the basis of a predefined set of quality standards. This usually involves a formal site visit by a team of surveyors [1]. The evaluation results in a decision on the granting of accreditation status. Accreditation has become a widespread tool for quality control and improvement in healthcare, and many resources are spent on developing and implementing accreditation systems across the world [2]. Nevertheless, solid evidence for the effects of accreditation is generally lacking, and this is particularly true for general practice [3, 4]. Only two effect studies on accreditation met the quality standards for inclusion in the first Cochrane review [5] on the subject, and none of these studies were about accreditation in general practice. Further, a review on the status of accreditation in primary care concluded that there is a dearth of research on the nature and uptake of accreditation in this sector along with how accreditation affects outcomes of care, and whether it is an effective method to improve quality, perceptions of care, healthcare utilization and costs [3]. In addition to a call for evidence of the clinical effects of accreditation, healthcare professionals have expressed concerns about the bureaucracy and the extra registration work imposed by accreditation.

In 2014 it was decided to implement a mandatory accreditation scheme in Danish general practice in the period 2016–2018. This protocol paper describes the design of a cluster-randomized evaluation of this accreditation scheme by means of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement for cluster-randomized trials (Additional files 1 and 2).

Methods/design

Participants and study design

The accreditation scheme in Denmark is rolled out as a cluster-randomized controlled trial (CRCT). All 1922 general practices are eligible for the study and are allocated to undergo accreditation in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively. Practices allocated to accreditation in 2016 (accreditation2016) and representing 604 clusters are selected as the intervention group, while practices allocated to accreditation in 2018 (accreditation2018) represent 648 clusters and serve as the control group. Practices are assigned an accreditation date 1 year in advance, and in order to avoid contamination from the intervention group, practices allocated to accreditation in 2017 (accreditation2017), representing 664 practices, will be excluded from analysis.

This design, in addition to the comprehensive Danish National Health registers, offers a unique opportunity to conduct research on the effects of accreditation [6–8]. Moreover, the design makes possible a comparison of practices that have already accomplished accreditation with practices waiting to be accredited [9]. Additionally, the national Civil Registration System (CRS) facilitates the collection of relevant data independent of the involved practices [10].

The Danish healthcare system is tax-financed, and most general practitioners (GPs) and hospital services are free of charge. General practice is characterized by five key components. (1) There is a list system associating citizens with a GP. GPs can close for uptake when they have 1600 persons on the list but are allowed to enroll up to 2550 persons. (2) The GP acts as gatekeeper and first-line provider in the sense that a referral from a GP is required for most office-based specialists and always for inpatient and outpatient hospital treatment. (3) An after-hours system is staffed by GPs on a rotation basis. (4) There is a mixed capitation and fee-for-service system. (5) GPs are self-employed, working on contract for the public funder based on a national agreement that details not only services and reimbursement but also opening hours and required postgraduate education [11]. Danish general practice constitutes 1922 practices comprising a total of 3329 GPs.

The accreditation program is developed and managed by the Danish Institute for Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare (IKAS). IKAS offers a range of accreditation programs, tailored for private hospitals, community pharmacies, community healthcare, general practice and specialist physicians practicing outside of a hospital setting.

One year in advance, practices are notified about their accreditation date by letter from IKAS. It is expected that practices will begin working with the standards from that date onwards.

Randomization

IKAS decided that surveys in all five regions of Denmark should be evenly distributed for the 3 years during which the accreditation process takes place. Moreover, it was decided by IKAS that the accreditation should be conducted by means of municipalities (each Danish region is divided into several smaller municipalities) and that the order of municipalities should be completely random.

Time for accreditation of the practices in the 98 municipalities in Denmark was determined in a randomized lots drawing conducted on 22 September 2014 by IKAS, and provided the basis for a prospective study. Two impartial persons from IKAS conducted the drawing. Within each of the five Danish regions, one-third of the practices within the municipalities that were drawn first were allocated to accreditation in 2016, the next third to 2017 and the last third to 2018. If large municipalities were drawn and this resulted in an excess of practices greater than one-third of the practices in a region, the practices were split over 2 allocation years based on the first letter in the street name in ascending order (Fig. 1).

This randomization allows for comparisons between early accredited practices (2016, n = 604 practices) and late accredited practices (2018, n = 648 practices) in 2017. Every practice is considered a cluster, which means that there are 1252 clusters in the study. The CRCT study is designed to comply with the recommendations of the CONSORT statement: extension to cluster-randomized trials [12] and SPIRIT.

Intervention

Since 2009 accreditation under the Danish Healthcare Quality Program (DHQP) has been mandatory in the secondary healthcare system in Denmark, and it was decided as part of ’the national strategy for quality development in the healthcare system – common aims and plan of action 2002–2006’. The DHQP has been adjusted to include general practice. The intervention comprises the rollout of a mandatory accreditation scheme, which is defined and carried out by an acknowledged, impartial institution: IKAS.

The DHQP is based on general principles for accreditation. The model contains a set of accreditation standards as well as an accreditation process [13]. The accreditation standards were developed by IKAS in collaboration with representatives from the Organization of General Practitioners in Denmark (PLO), Danish Regions, Danish Patients, and the Danish Association of Practicing Medical Specialists. A preliminary version of the standard set was pilot-tested in 26 practices in 2012 [14]. Subsequently, the standard set was further adjusted, and the Danish Regions and the PLO approved the current version in 2014.

The DHQP for general practice consists of 16 standards with associated indicators within the following areas: (1) quality and patient safety, (2) patient safety critical standards, (3) good patient continuity of care and (4) management and organization [13].

The standards include certain minimal requirements, but are also written to stimulate quality improvement. Not everything in the standards is written to describe and delineate precisely what the client should do. Parts of the standards are intended to stimulate reflection on one’s own practice and thereby inspire improvement activities.

Each standard includes a descriptive part, where the purpose and meaning of the standard is explained in more or less detail, as appropriate. Furthermore, each standard includes a number of indicators that comprise the measurable elements of the standard set. Compliance with the standard set is assessed by rating of the indicators. The surveyor team does this during survey.

A survey implies a visit from a surveyor team consisting of healthcare professionals who have received specific training to handle this task. Some surveyors in the practice sectors are IKAS employees, but all survey teams will include surveyor(s) who are peers, working most of their time in healthcare.

The survey has a dual purpose: to assess compliance with minimal requirements and to identify opportunities for improvement, even when the threshold for obtaining accreditation has been reached. A client needs to comply with the minimal requirements in order to obtain accreditation. But the survey should also give the client feedback on his or her efforts to meet the purpose of the standards, and it should do this in a way that inspires and supports quality improvement work.

Compliance assessment is governed by defined rating principles. The fundamentals are the same for all programs:

-

Met: The client in all essentials complies with the requirements in the indicator.

-

Largely Met: There are opportunities for improvement, but accreditation can be awarded; no further action is required.

-

Partially Met: There are opportunities for improvement, and action is required, unless accreditation is awarded with comments or, in case of critical non-compliances, is denied.

-

Not Met: There is no evidence for compliance or only plans to achieve compliance [13].

The standards are accompanied by rating principles, describing how compliance with the indicators is assessed and rated [13].

Objectives

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of accreditation in general practice with regard to certain clinical outcomes (Fig. 2).

Clinical outcomes

The selected outcomes should meet the following criteria: (1) a high degree of clinical relevance, (2) the possibility to assess changes due to accreditation, (3) the availability of data independent of self-reporting from practices. Table 1 lists GPs and practice characteristics. The selected outcomes, their origin from the DHQP and the used data collection sources are listed in Table 2.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the changes in number of prescribed drugs in patients older than 65 years between the baseline and follow-up period.

This outcome refers to standard 2.2 in the DHQP: physicians in the practice have knowledge about the basic list for rational pharmacotherapy. The practice conducts, according to medical judgments, annual controls in patients with chronic disease, comprising assessment of prescriptions.

The primary outcome is selected because inappropriate use of many concurrent drugs, especially in older people, imposes a substantial burden of adverse drug events, ill health, disability, hospitalization and even death. The single most important predictor of inappropriate prescribing adverse drug events (ADEs) in older patients is the number of prescribed drugs [15]. One report estimated the risk of ADE as 13% for two drugs, 38% for four drugs and 82% for seven drugs or more [15]. A Danish study from 2000 showed that among 75-year-old persons living at home, 60% used three or more prescribed drugs and 34% used five or more [16]. A more recent study performed by the pharmacist foundation found that almost 40% of the elderly older than 65 years use six or more drugs, while this is the case for more than 50% of the elderly older than 80 years [17]. National guidelines for general practice recommend critical reviews of the elderly patients’ medication [18], and secure medication in elderly patients relates to all four areas in DHQP.

It is not possible to assess whether the medication given to the individual patient is reasonable, as we have no access to the patients’ diagnosis or the indication. Therefore, we will analyse any changes in number of drugs in elderly persons (older than 65) for accredited practices and non-accredited practices.

Our main hypothesis is that implementing DHQP will decrease the number of prescribed drugs during the accreditation scheme.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes focus on safe medication practices, good clinical practices and quality and patient safety according to the DHQP. These outcomes relate directly to one of the standards concerning critical patient safety issues (standard 2.2), and they are expressed as changes in amounts or prevalence between the observation period and the baseline period.

The rationale for each of the secondary outcomes is presented in Table 2.

Safe medication

Safe medication use includes:

-

Changes in the proportion of polypharmacy (>5 prescribed drugs) patients older than 65 years

-

Changes in daily drug dose (DDD) of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) without proton pump inhibitor (PPI)

-

Changes in DDD of sleeping medicine.

Good clinical practice

Good clinical practice includes:

-

Changes in the proportion of elderly persons older than 75 receiving a preventive home visit (PHV)

-

Changes in the number of annual controls for chronic disease (ACCD) between periods

-

Changes in the number of spirometries performed

-

Quality and patient safety:

-

Changes in proportion of practices with a reported adverse event (RAE)

-

Changes in proportion of practices with a patient satisfaction survey between periods.

Mortality

Mortality is evaluated as changes in mortality rates between periods.

Data collecting periods

All outcomes except mortality are surveyed in the following two periods:

-

1.

Baseline data are collected from 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2014.

-

2.

Follow-up data are collected from 1 January 2017 to 30 June 2017.

For mortality the periods are:

-

1.

Baseline data are collected from 30 June2014 to 31 August 2014.

-

2.

Follow-up data are collected from 30 June 2017 to 31 August 2017.

Data sources

Data on clinical effects measures are prospectively collected and stored within various national registers. However, the project group does not have permission to retrieve data until autumn 2017. Prescription data from 2015 formed the basis for the power analysis. Because of the CRS, these data can be linked to the patients’ civil registration number and analysed within a common research database hosted by Statistics Denmark (StatDen) and Statens Serum Institut (SSI). A named responsible statistician will obtain permission to work with data within the frames of StatDen.

We will use the National Prescription Register (NPR), which is a database that includes records of all prescriptions dispensed at all Danish community pharmacies since 1995 (information on drugs administered to hospital inpatients is not registered) to calculate the number of drugs per patients based on the date a prescription is redeemed, the pharmaceutical group (ATC code 4) and the DDD in the redeemed prescription. Based on this information, we will calculate the number of pharmaceutical groups through which an individual redeemed prescriptions on 30 June in the years 2014 and 2017.

The Danish Register of Causes of Death (DRCD), which includes information on specific causes of death based on death certificates, will be used to define all-cause mortality.

GP and practice characteristics and services provided (e.g. spirometry and annual check-ups for chronic conditions) will be retrieved from the Danish National Health Services Register (DNHSR).

All baseline data are available in the mentioned registers/databases and will be retrieved starting from autumn 2017.

Statistics

Differences in baseline characteristics are reported as numbers (percentages) and tested using chi-squared tests.

Linear regression will be used for continuously valued outcomes (e.g. number of different drugs, safe medication, annual controls, etc.) and logistic regression for binary outcomes (polypharmacy, preventive home visits, changes in proportion of practices with reported adverse events and changes in proportion of practices with a patient satisfaction survey). Analyses will account for clustering of patients in practices by generalized estimating equations (GEE). A level of 5% will be taken as statistically significant.

Analyses will be performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

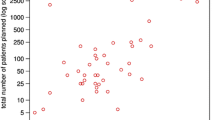

Power calculation

The mean number of Danes older than 65 years allocated to an average practice is 584 (standard deviation (SD) 378; registry data at the start of 2015). The mean number of redeemed prescriptions per patient among Danes older than 65 years is 6.59 (SD 5.04; registry data over the full year 2014). For the power calculation, the intra-class correlation (ICC) is set relatively high at 0.2.

Using the formulae in Hemming et al. [19], we are able with our data to detect a difference from a mean number of prescriptions of 6.59 in the control group to 6.13 in the accreditation group using a t test with a 5% level of significance accounting for clustering within practices with a power of 80%.

Trial status

Randomization has been conducted. Power calculations are based on prescription data from 2015. All practices and GPs have been recruited. Data on clinical effects measures are prospectively collected and stored within various national registers. However, the project group does not have permission to retrieve data until autumn 2017.

Discussion

The consequences of accreditation and standard-setting processes are generally under-researched; this is particularly true in general practice. This paper describes the rationale and design of the first cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate the clinical effects of a nation-wide accreditation scheme in general practice, focusing on the effects of accreditation on changes in the number of prescribed drugs in patients older than 65 years. Our study is in accordance with several recent calls for more research into the clinical effects of accreditation in healthcare [3, 5, 9, 20, 21]. This is the first study with a CRCT approach to measure clinical effects of accreditation in general practice. Thus, the knowledge emanating from this study will be unique, and the study may set a benchmark for more research.

The study is an effectiveness study based on register data, and thus is not dependent on inputs from participants or their willingness to participate; hence, the occurrence of information and selection bias is reduced. Moreover, the randomization seems to be successful, as GPs and their practices do not differ between accreditation years.

Randomization group sizes were dependent on allocation and determined by IKAS; thus, this decision was out of the hands of the project group. Allocation was conducted by draw, and the persons who drew lots were impartial. The decision on excluding practices allocated to accreditation in 2017 from the analysis was logical and pragmatic, as any spillover effect from the intervention group accreditation year 2016 is suggested to be largest for accreditation year 2017 and least for accreditation year 2018.

Experiences from the French healthcare system suggest that accreditation risks being reduced to a matter of standardizing practices rather than a matter of improving quality [22]. Therefore, our study primarily focuses on clinically relevant quality indicators relating to the DHQP. The research group scrutinized the standards in the accreditation scheme, and the final list of endpoints was established according to relevant outcomes from a clinical perspective. The direction of changes for some of the chosen outcomes is ambiguous; e.g. polypharmacy can be appropriate in patients with multi-morbidity, but it may also be a result of a lack of treatment plans and medicine reviews. However, according to several national guidelines and systematic reviews, polypharmacy should be reduced, especially among the elderly.

Because the accreditation scheme is mandatory for all Danish GPs, the results are expected to be representative for the effects of accreditation in Danish general practice. Extrapolation to other countries requires further consideration due to differences in the organization of healthcare systems and cultural factors.

The Danish GPs have been informed about the forthcoming accreditation at least 12 months ahead. It may be assumed that some practices will prepare their accreditation in good time as part of their practice development work. Further, some spillover effects must be expected from practices undergoing accreditation to practices awaiting accreditation. Therefore, we collect baseline data from the first half of 2014, and leave out the 2017 population in our analysis.

The GPs allocated to the three clusters did not differ statistically significantly in gender, practice type or region. Therefore, we assume that eventual changes in performance cannot be ascribed to selection.

Abbreviations

- ACCD:

-

Annual controls for chronic disease

- ADE:

-

Adverse drug event

- AKIAP:

-

Accreditation in general practice

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRS:

-

Civil Registration System

- DANPEP:

-

Danish Patients Evaluate Practice

- DDD:

-

Daily drug dose

- DHQP:

-

Danish Healthcare Quality Programme

- DNHSR:

-

Danish National Health Services Register

- DPSD:

-

Danish Patient Safety Database

- DRCD:

-

Danish Register of Causes of Death

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- IKAS:

-

Danish Institute for Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare

- MD:

-

Medication Database

- NPR:

-

National Prescription Register

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PHV:

-

Preventive home visit

- PLO:

-

Organization of General Practitioners in Denmark

- PPI:

-

Proton pump inhibitor

- RAE:

-

Reported adverse event

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SSI:

-

Statens Serum Institut

- StatDen:

-

Statistics Denmark

References

Braithwaite J, Westbrook J, Pawsey M, Greenfield D, Naylor J, Iedema R, et al. A prospective, multi-method, multi-disciplinary, multi-level, collaborative, social-organisational design for researching health sector accreditation [LP0560737]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:113.

Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Moldovan M, Westbrook JI, Pawsey M, Mumford V, et al. Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(12):979–91.

O'Beirne M, Zwicker K, Sterling PD, Lait J, Lee Robertson H, Oelke ND. The status of accreditation in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2013;21(1):23–31.

Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(3):172–83.

Flodgren G, Pomey MP, Taber SA, Eccles MP. Effectiveness of external inspection of compliance with standards in improving healthcare organisation behaviour, healthcare professional behaviour or patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD008992.

Erlangsen A, Fedyszyn I. Danish nationwide registers for public health and health-related research. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(4):333–9.

Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Bronnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):12–6.

Thygesen LC, Ersboll AK. Danish population-based registers for public health and health-related welfare research: introduction to the supplement. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):8–10.

Sunol R, Nicklin W, Bruneau C, Whittaker S. Promoting research into healthcare accreditation/external evaluation: advancing an ISQua initiative. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(1):27–8.

Eriksson T, Hundborg K, Friborg S. Accreditation of Danish general practice. Integrated quality development and continuing education. Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171(20):1684–8.

Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Sondergaard J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25 Suppl 1:S34–8.

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Group C. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661.

IKAS. The Danish Healthcare Quality Programme 2015. Aarhus: IKAS; 2015.

Rambøll. Evaluering af DDKM i almen praksis. Copenhagen: Rambøll; 2012.

Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology of serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1999;14(2):141–52.

Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM. The consumption of drugs by 75-year-old individuals living in their own homes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56(6-7):501–9.

Apotekerforeningen. Analysis – 700,000 Danes are polypharmacy patients. Copenhagen: The Pharmacist Association (Apotekerforeningen); 2012. http://www.apotekerforeningen.dk/~/media/Apotekerforeningen/analysersundhed/19122012_polyfarmacipatienter.ashx. Accessed 19 Dec 2012.

DSAM. The elderly patient. Copenhagen: The Danish College of General Practitioners (DSAM); 2012. p. 81. http://www.dsam.dk/files/9/den_aeldre_patient_okt2012.pdf. Accessed Oct 2012.

Hemming K, Girling AJ, Sitch AJ, Marsh J, Lilford RJ. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised controlled trials with a fixed number of clusters. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:102.

Braithwaite J, Westbrook J, Johnston B, Clark S, Brandon M, Banks M, et al. Strengthening organizational performance through accreditation research — a framework for twelve interrelated studies: the ACCREDIT project study protocol. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:390.

Shaw CD. Evaluating accreditation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(6):455–6.

Pomey MP, Francois P, Contandriopoulos AP, Tosh A, Bertrand D. Paradoxes of French accreditation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):51–5.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Anna Mygind Rasmussen and Thorkil Thorsen for helpful discussions during the development of the paper.

Funding

The project is funded by in-house research resources and received non-restricted grants from the Danish Institute for Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare.

Availability of data and materials

The data will be available from The Research Unit of General Practice, University of Southern Denmark. Professor Frans Boch Waldorff is responsible for the data.

Authors’ contributions

MKA participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and drafted the paper. LBP participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and critically revised the paper. VS performed the power calculations and critically revised the paper. FB participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and critically revised the paper. SR participated in the design of the study and read and approved the paper. JS participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and read and approved the paper. MBK participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and critically revised the paper. FBW participated in the design of the study, developed the outcomes and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The project group gives consent for the paper to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by The Research Ethics Committee for the Region of Southern Denmark: file number S-20152000-178 and The Danish Data Protection Agency: J.nr. 2016-41-4579 according to the personal data law §50, part 1, number 1.

Declarations

All data on GPs and patients are anonymized, and data will only be obtainable for a named, responsible statistician.

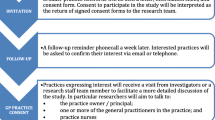

Recruitment and consent

The planned accreditation scheme is mandatory for all general practices with the exception of practices expected to terminate within 5 years. Data are anonymized and drawn from registers, which means that the GPs should not actively take part in the data collection. Moreover, according to Danish law, register-based research does not fall within the scope of ethic assessment, and no consent is required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

CONSORT extension for cluster trials checklist. (DOCX 36 kb)

Additional file 2:

SPIRIT checklist. (DOC 121 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, M.K., Pedersen, L.B., Siersma, V. et al. Accreditation in general practice in Denmark: study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 18, 69 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1818-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1818-6