Abstract

RNA contains over 150 types of chemical modifications. Although many of these chemical modifications were discovered several decades ago, their functions were not immediately apparent. Discoveries of RNA demethylases, along with advances in mass spectrometry and high-throughput sequencing techniques, have caused research into RNA modifications to progress at an accelerated rate. Post-transcriptional RNA modifications make up an epitranscriptome that extensively regulates gene expression and biological processes. Here, we present an overview of recent advances in the field that are shaping our understanding of chemical modifications, their impact on development and disease, and the dynamic mechanisms through which they regulate gene expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

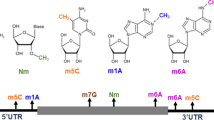

Over 150 unique chemical modifications of RNA have been found in different organisms. The first of these modifications was discovered in 1951, when ion-exchange analysis of RNA revealed an abundant unknown modification later identified as pseudouridine (Ψ) [1,2,3,4]. Discoveries of other abundant modifications using radioactive labeling followed: 2′-O-methylation (2′OMe) and N 1-methyladenosine (m1A) were discovered in tRNA and ribosomal RNA (rRNA); and 2′OMe, N 6-methyladenosine (m6A) and 5-methylcytidine (m5C) were found in mRNA and viral RNA [5,6,7,8]. As the modifications were systematically characterized and catalogued, hints to their functions emerged. m6A, the most abundant internal modification of eukaryotic mRNA, was shown in early studies to facilitate the processing of pre-mRNA and the transport of mRNA [9, 10].

We proposed previously that post-transcriptional RNA modifications could be reversible and may significantly impact the regulation of gene expression [11]. This hypothesis was confirmed with the discovery of fat-mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO), the first enzyme known to demethylate m6A on RNA, soon followed by that of alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5), a second m6A demethylase [12, 13]. In 2012, m6A-specific antibodies were used to profile m6A sites through immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing. Thousands of m6A sites were identified in human and mouse cell lines, with enrichment around the stop codon and 3′ UTR [14, 15]. These advances sparked extensive research on RNA post-transcriptional modifications in this new era of epitranscriptomics. In this review, we summarize the most recent advances in the field, focusing on functional investigations.

m6A writers and readers lead the way

m6A is installed by a methyltransferase complex that includes the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) binding protein methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), first identified over two decades ago [16, 17] (Fig. 1). Recent experiments have established that METTL3 and METTL14 are essential components of a writer complex, in which METTL3 is catalytically active while METTL14 has critical structural functions [18, 19]. Functional roles of m6A were discovered through experiments in which METTL3 was inactivated; these studies showed that loss of m6A compromises circadian rhythm, embryonic stem cell fate transition, and naïve pluripotency [20,21,22]. A new m6A methyltransferase, METTL16, has been shown to regulate the splicing of the human SAM synthetase MAT2A, promoting its expression through enhanced splicing of a retained intron in SAM-depleted conditions, and thus acting as a regulation loop [23]. METTL16 was also shown to be the m6A methyltransferase of the U6 small nuclear RNA.

The m6A machinery. The writers, readers, erasers, and cellular components of eukaryotes that interact with m6A and the RNA that contains it. A adenosine, ALKBH5 AlkB homologue 5, eIF3 eukaryotic initiation factor 3, FTO fat-mass and obesity-associated protein, HNRNPC heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C; m 6 A N 6-methyladenosine, METTL3 methyltransferase-like 3, RNAPII RNA polymerase II, YTHDC1 YTH domain containing 1, YTHDF1 YTH domain family 1

Importantly, m6A regulates gene expression through various m6A-recognition proteins. YTH domain containing 1 (YTHDC1), an m6A ‘reader’, acts in the nucleus to influence mRNA splicing [24], whereas heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (HNRNPC) and HNRNPG bind to RNAs whose structures have been altered by m6A to promote mRNA processing and alternative splicing [25, 26]. In the cytosol, the m6A readers YTH domain family 1 (YTHDF1) and YTHDF3 affect the translation of their targets through ribosome loading in HeLa cells [27,28,29], and YTHDF2 facilitates mRNA degradation by recruiting the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex [30, 31]. The m6A reader YTHDC2 also functions in the cytosol, affecting the translation efficiency and mRNA abundance of its targets [32]. As research elucidates the functions of m6A readers, it is becoming evident that their roles may be complex. m6A in the 5′ UTR could facilitate cap-independent translation initiation through a process involving eIF3 [33, 34]. The exact ‘reading’ mechanism of this process is still unclear. Under heat shock, YTHDF2 shields 5′ UTR m6A from FTO, allowing selective mRNA translation. It will be important to determine the functional roles of readers under different biological conditions.

Effects of m6A at the molecular level

m6A appears to influence almost every stage of mRNA metabolism. Three recent studies demonstrated interactions with the translation, transcription, and microprocessor machineries (Fig. 1). In an Escherichia coli translation system, the presence of m6A on mRNA interferes with tRNA accommodation and translation elongation [35]. Although m6A does not interfere with the structure of the codon–anticodon interaction, minor steric constraints destabilize base-pairing. The magnitude of the resulting delay is affected by the position of the m6A, implying that m6A may be an important regulator of tRNA decoding. m6A was also shown to be correlated with decreased translation efficiency in a study using MCF7 cells [36]. In this experiment, an inducible reporter system was used to demonstrate that transcripts with slower rates of transcription received greater deposition of m6A, and that m6A deposition occurs co-transcriptionally. This work also showed that METTL3 interacts with RNA polymerase II under conditions of slower transcription, and that methylated transcripts had decreased efficiency of translation. As m6A has been shown to promote translation in other studies [27, 33, 34], the role of m6A in affecting translation could be transcript- and position-dependent. Although the m6A itself could reduce translation efficiency, as shown in the in vitro experiment [35], the YTH domain proteins could promote translation in response to stimuli or signaling. A recent study showed that METTL3 binds to RNA co-transcriptionally, and that this interaction is necessary for the microprocessor components Dgcr8 and Drosha to associate physically with chromatin to mediate gene silencing [37]. METTL3 and Dgcr8 relocalize to heat-shock genes under hyperthermia and work in concert to promote the degradation of their targets, allowing timely clearance of heat-shock responsive transcripts after heat-shock has ended. These studies reveal important roles for m6A in enhancing the dynamic control of gene expression, a function that is especially important under changing cell conditions.

Influences of m6A on development and differentiation

We recently proposed that m6A shapes the transcriptome in a manner that facilitates cell differentiation [38]. Such a role could be critical during development, as is suggested by several recent studies. m6A is necessary for sex determination in Drosophila [39, 40]. Depletion of the Drosophila METTL3 homologue Ime4 leads to the absence of m6A on the sex determination factor Sex lethal (Sxl). Without m6A, the YTHDC1 homologue YT521-B is unable to properly splice Sxl, leading to failure of X inactivation and thus improper sex determination. Moreover, depletion of Ime4 affects neuronal function, causing shortened lifespan and irregularities in flight, locomotion, and grooming. m6A has also been shown to regulate the clearance of maternal mRNA during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in zebrafish [41]. Zebrafish embryos that lack the m6A reader Ythdf2 become developmentally delayed because of impaired decay of m6A-modified maternal RNAs. Because these maternal RNAs are not properly decayed, activation of the zygotic genome is also impaired.

Previous studies have demonstrated roles for m6A in the differentiation of mouse and human embryonic stem cells [21, 22, 42]. More recently, effects of m6A on differentiation have been shown in mice. Two separate studies showed that the meiosis-specific protein MEIOC, which is necessary for proper meiotic prophase I during spermatogenesis, interacts with the m6A reader YTHDC2 [43, 44]. Mice that lack Meioc are infertile, lacking germ cells that have reached the pachytene phase of meiotic prophase I. Notably, mice lacking Ythdc2 or Mettl3 display similar phenotypes, demonstrating infertility and defects in germ cells, which reach a terminal zygotene-like stage and undergo apoptosis [32, 45]. m6A also affects somatic cell differentiation in mice. Knockout of Mettl3 in mouse T cells caused failure of naïve T cells to proliferate and differentiate; in a lymphopaenic adoptive transfer model, most naïve Mettl3-deficient T cells remained naïve, and no signs of colitis were present [46]. The lack of Mettl3 caused upregulation of SOCS family proteins, which inhibited the IL-7-mediated STAT5 activation necessary for T cell expansion. Two studies of FTO have also demonstrated roles for m6A in somatic cell differentiation. FTO expression was shown to increase during myoblast differentiation, and its depletion inhibited differentiation in both mouse primary myoblasts and mouse skeletal muscle [47]. The demethylase activity of FTO is required: a point mutation of FTO that removes demethylase activity impairs myoblast differentiation. FTO is also dynamically expressed during postnatal neurodevelopment, and its loss impedes the proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stem cells [48].

Involvement of m6A in human cancer

As discussed in the previous section, m6A is a critical factor in cell differentiation. Considering that cancer is driven by the misregulation of cell growth and differentiation, it follows that cancer cells may hijack aberrant methylation to enhance their survival and progression. Several studies have demonstrated roles for demethylation or lack of methylation in promoting cancer progression. In MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FTO is highly expressed, promotes oncogene-mediated cell transformation and leukemogenesis, and inhibits all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced AML cell differentiation [49]. At the molecular level in AML, FTO causes both a decrease in m6A methylation and a decrease in the transcript expression of these hypo-methylated genes. ASB2 and RARA are functionally important targets of FTO in MLL-rearranged AML; their forced expression rescues ATRA-induced differentiation. The oncogenic role of FTO is not limited to AML; another study showed that inhibition of FTO in glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) suppresses cell growth, self-renewal, and tumorigenesis [50]. This study demonstrated that other components of m6A machinery also impact glioblastoma. Knockdown of METTL3 or METTL14 affects the mRNA expression of genes that are crucial to GSC function, and enhances GSC growth, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. In agreement with these findings that lack of methylation tends to promote cancer progression, Zhang et al. [51] showed that ALKBH5 is highly expressed in GSCs, and that its knockdown suppresses their proliferation. The protein abundance of the ALKBH5 target FOXM1 is greatly increased in GSCs as a result of the demethylation activity of ALKBH5; removal of m6A at the 3′ end of FOXM1 pre-mRNA promotes FOXM1 interaction with HuR, which enhances FOXM1 protein expression. A long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) antisense to FOXM1 facilitates the interaction between ALKBH5 and FOXM1, and depletion of either ALKBH5 or its antisense lncRNA inhibits GSC tumorigenesis. ALKBH5 also promotes a breast cancer phenotype; under hypoxic conditions, ALKBH5 expression increases, thus decreasing levels of m6A and upregulating expression of the pluripotency factor NANOG [52].

Together, the studies mentioned above suggest that a decrease in RNA m6A methylation tends to facilitate cancer progression, and that RNA methylation could affect cell growth and proliferation. Other studies, however, indicate that the role of m6A in different cancers may be more complex. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), METTL14 downregulation is associated with tumor metastasis, but METTL3 enhances the invasive ability of HCC cells [53]. Several other studies also point to an oncogenic role for the methyltransferase complex. METTL3 plays an oncogenic role in cancer cells, promoting the translation of cancer genes through interactions with the translation initiation machinery [54]. Interestingly, METTL3 promotes translation independent of its methyltransferase activity or of any interaction with the m6A reader YTHDF1. WTAP, a component of the m6A methyltransferase complex, also promotes leukemogenesis, and its levels are increased in primary AML samples [55]. RBM15, another methyltransferase complex component, is altered in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia, undergoing translocation to fuse with MKL1 [56].

Considering the complex findings, it is likely that different types of cancers can be derived from unique imbalances or misregulation of mRNA methylation. In AML, increased WTAP and RBM15 expression (or writer proteins themselves) could block differentiation, leading to leukemia, whereas increased eraser expression could cause leukemia via separate pathways. The intricate network of interactions is reminiscent of studies of DNA methylation; just as misregulation of DNMT and TET proteins are both associated with cancer [57,58,59,60], misregulation of the m6A machinery can lead to cancer through unique mechanisms. Interestingly, the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2-HG), which could act as a nonspecific inhibitor of the iron- and αKG-dependent dioxygenases FTO and ALKBH5, accumulates in about 20% of AMLs [61], and may thus contribute to the outcome of these cancers by inhibiting RNA demethylation. Further investigation is necessary to uncover mechanisms by which aberrant methylation affects the proliferation of various cancers.

Other modifications on mRNA

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing and mass spectrometry have revitalized research on post-transcriptional modifications, elucidating functions of both known and newly discovered modifications on mRNA (Fig. 2).

Methylation of the N 1 position of adenosine (m1A) was recently discovered on mRNA; this modification was found to occur on RNA at levels around 10–30% of that of m6A, depending on the cell line or tissue [62, 63]. m1A occurs in more structured regions and is enriched near translation initiation sites. The level of m1A responds dynamically to nutrient starvation and heat shock, and the 5′ UTR peaks correlate with translation upregulation. As it is positively charged, the m1A modification may markedly alter RNA structure as well as RNA interactions with proteins or other RNAs. Zhou et al. [64] demonstrated that m1A causes A-U Hoogsteen base pairs in RNA to be strongly disfavored, and that RNA that contains m1A tends to adopt an unpaired anti conformation. m1A was also shown to affect translation; its presence at the first or second codon position, but not at the third codon, blocks translation in both Escherichia coli and wheat germ extract systems [65]. In addition, m1A is present in early coding regions of transcripts without 5′ UTR introns, which are associated with low translation efficiency and which facilitate noncanonical binding by the exon junction complex [66]. These studies point to a main role of m1A in translation and RNA–RNA interactions. The exact functional roles of 5′ UTR m1A sites require further studies, and there are also other m1A sites in mRNA that could play distinct roles. Methods to map low abundance m1A sites in mRNA will be crucial to understanding their biological roles [67].

Adenosines at the second base of mRNAs can also undergo both 2′-O-methylation and m6A methylation to become m6Am, a modification with an unidentified methyltransferase [68, 69]. m6Am was recently profiled at single-nucleotide resolution by crosslinking RNA to m6A antibodies and then identifying mutations or truncations in reverse transcription by high-throughput sequencing [70]. It undergoes preferential demethylation by FTO. The study by Mauer et al. [70] revealed negligible effects of FTO on internal mRNA m6A in vitro and inside cells. However, this is not consistent with the findings of many previous biochemical and cell-based studies [12, 34, 49, 71, 72]; clear sequential m6A demethylation by FTO has been demonstrated biochemically [71]. FTO works on both m6A and m6Am, with greater demethylase activity toward m6A modifications that are located internally on mRNA when ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) is used to quantify modification changes in a range of different cell lines. Because FTO can work on multiple substrates, including m6Am, and m6Am methylation occurs on only a fraction of all mRNA [73], it will be critical to determine the functional relevance of m6Am demethylation as has been done with internal m6A demethylation [34, 49, 72]. The methyltransferase will need to be identified and the phenotypes of knockout mice and cell lines will need to be examined carefully.

Cytosine methylations are also prevalent in RNA. m5C was first identified on RNA more than 40 years ago, and is present in all three domains of life [74]. It has been sequenced on mRNA using bisulfite sequencing, and was found to be highly prevalent in both coding and non-coding RNA [75, 76]. Bisulfite sequencing of m5C on mRNA may, however, produce false positives due to incomplete deamination of unmodified cytidines. Although several biological functions of m5C have been discovered on tRNA (as discussed in the following section), the biological functions of m5C in mRNA have remained largely elusive. Recently, however, a function of m5C on mRNA was recently discovered by Yang et al. [77]: m5C promotes nuclear export because it is specifically recognized by the mRNA export adaptor ALYREF. Notably, the study by Yang et al. [77] found enrichment of m5C sites located 100 nucleotides after translation initiation sites, which were not observed by previous studies. Further studies on the enzymes that interact with m5C may lead to the discovery of additional roles for m5C in mRNA.

3-Methylcytosine was recently identified as a modification in mRNA, present at a rate of around 0.004% of cytosines in human cell cultures [78]. It is installed by METTL8, and its function and localization have yet to be identified.

Pseudouridine, which is generated by isomerization of uridine, is the most abundant RNA modification in total RNA [3]. It was recently identified on mRNA and mapped by several groups using similar techniques (PseudoU-seq, Ψ-seq, PSI-seq, and CeU-seq), which use the water-soluble diimide CMCT (1-cyclohexyl-3-(2-morpholinoethyl)-carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulfonate) to generate strong reverse transcriptase stops at ψ sites [79,80,81,82]. PseudoU-seq and Ψ-seq identified > 200 and > 300 sites, respectively, on human and yeast mRNAs, and Ψ/U in mRNA has been quantified at around 0.2–0.7% in mammalian cell lines. Direct evidence of biological functions of Ψ on mRNA has yet to be identified, but several findings point to potential biological roles. Ψ affects the secondary structure of RNA and alters stop codon read through [83, 84]. Depletion of the pseudouridine synthase PUS7 decreases the abundance of mRNAs containing Ψ, suggesting that Ψ may also affect transcript stability [80]. Moreover, pseudouridinylation on transcripts is affected by stresses such as heat shock and nutrient deprivation, suggesting that Ψ may be a response to various stresses [79, 80, 82].

Modifications on transfer RNAs and other RNAs

tRNAs contain more modifications than any other RNA species, with each tRNA containing, on average, 14 modifications [74]. Recent studies have identified tRNA demethylases and methyltransferases, as well as the functions of their modifications.

Liu et al. [85] recently identified a tRNA demethylase for the first time; ALKBH1 demethylates m1A58 in tRNAiMet and several other tRNA species. m1A58 increases tRNAiMet stability, and its demethylation by ALKBH1 decreases the rate of protein synthesis. A related demethylase, ALKBH3, removes m6A from tRNA and increases translation efficiency in vitro, though its cellular targets and functions have yet to be identified [86].

m5C on tRNA can also influence translation, particularly affecting stress responses. Deletion of the tRNA m5C methyltransferase NSUN2 reduces tRNA m5C levels and promotes cleavage of unmethylated tRNAs into fragments, which decrease protein translation rates and induce stress response pathways [87]. Lack of Nsun2 in mice leads to an increase in undifferentiated tumor stem cells due to decreased global translation, which increases the self-renewal potential of the tumor-initiating cells [88]. Interestingly, lack of Nsun2 also prevents cells from activating survival pathways when treated with cytotoxic agents, suggesting that the combination of m5C inhibitors and chemotherapeutic agents may effectively treat certain cancers.

m5C also plays an important role in the translation of the mitochondrial tRNA for methionine (mt-tRNAMet). m5C is deposited onto cytosine 34 of mt-tRNAMet by the methyltransferase NSUN3 [89,90,91]. Lack of NSUN3 leads to deficiencies such as reduced mitochondrial protein synthesis, reduced oxygen consumption, and defects in energy metabolism. Mutation of NSUN3 is also associated with several diseases, including maternally inherited hypertension and combined mitochondrial respiratory chain complex deficiency. Mechanistically, m5C is oxidized by ALKBH1/ABH1 into 5-formylcytidine, which is necessary for reading the AUA codon during protein synthesis.

Methylation and editing of tRNA may require intricate mechanisms and conditions. NSun6, which installs m5C72 onto tRNA, recognizes both the sequence and shape of tRNA [92]. Without a folded, full-length tRNA, NSun6 does not methylate m5C72. C-to-U deamination of C32 in Trypanosoma brucei tRNAThr also depends on multiple factors [93]. Methylation of C32 to m3C by two enzymes, the m3C methyltransferase TRM140 and the deaminase ADAT2/3, is a required step in the deamination process. m3C must then be deaminated to 3-methyluridine (m3U) by the same mechanism, and m3U is then demethylated to become U.

The recent discoveries of the first tRNA demethylases, of their effects on translation and differentiation, and of complex mechanisms of tRNA methylation and editing will undoubtedly inspire investigations to elucidate the functions of tRNA modifications and the biological processes to which they respond.

Ribosomal RNA is also marked by abundant modifications; the > 200 modified sites in human rRNAs make up around 2% of rRNA nucleotides. Most modifications on rRNA are Ψ or 2′OMe, although rRNA also contains around ten base modifications [74]. Functions of rRNA modifications are largely unknown, but studies of 2′OMe on rRNA are beginning to provide hints to their functions. The C/D box snoRNAs SNORD14D and SNORD35A, which are necessary to install 2′OMe onto rRNA, are necessary for proper leukemogenesis and are upregulated by leukemia oncogenes [94]. C/D box snoRNA expression in leukemic cells is correlated with protein synthesis and cell size, suggesting a potential role for 2′OMe on rRNA in translation.

The processing and functions of other non-coding RNA species have recently been shown to undergo regulation by m6A. Alarcón et al. [95] demonstrated that pri-microRNAs contain m6A, which is installed by METTL3 and promotes recognition and processing into mature microRNA by DGCR8. m6A is also present on the lncRNA XIST, and is necessary for XIST to mediate transcriptional silencing on the X chromosome during female mammalian development [96]. Finally, m6A is present on human box C/D snoRNA species; it impedes the formation of trans Hoogsteen-sugar A–G base pairs, thus affecting snoRNA structure, and also blocks binding by human 15.5-kDa protein [97].

Concluding remarks and future directions

It is becoming increasingly clear that the epitranscriptome and its modifying enzymes form a complex constellation that holds widely diverse functions. Post-transcriptional RNA modifications allow additional controls of gene expression, serving as powerful mechanisms that eventually affect protein synthesis. In particular, m6A provides layers of regulation, offering effects that are dependent on the localization of its writers, readers, and erasers.

To facilitate certain cellular processes, the m6A machinery can target multiple substrate mRNAs and non-coding RNAs. As we proposed [38], cellular programs may require a burst of expression of a distinct set of transcripts, followed by expression of a different set of transcripts. m6A can mark and cause timely expression and turnover of subsets of transcripts. The cellular and compartmental localizations of the writers, readers, and erasers critically affect their functions. Methylation, together with demethylation of subsets of transcripts in the nucleus, may create a methylation landscape that directs the fate of groups of transcripts as they are processed, exported to the cytoplasm, translated, and degraded. Multiple different readers or their associated proteins may be required to actualize the effects of the methylations fully. Although transcript turnover or decay is an accepted role of mRNA m6A methylation, it should be noted that the Ythdf2 knockout mouse exhibits a less severe phenotype [98] compared to mice lacking Mettl3 or Mettl14 (embryonic lethals), demonstrating that the Ythdf2-dependent pathway mediates a subset of the functions of methylated transcripts. There are other crucial regulatory functions of m6A RNA methylation that remain to be uncovered.

These observations lead us to perceive that methylation occurs at multiple layers. Methyltransferases set the initial methylation landscape in coordination with the transcription machinery. Demethylases could more efficiently tune the methylation landscape of a subset of methylated transcripts, acting as the second layer of regulation. Indeed, demethylases often target only a subset of genes under certain conditions; for example, depletion of Alkbh5 does not lead to embryonic lethality but instead causes defects in spermatogenesis [13], and only a portion of Fto knockout mice display embryonic lethality. Finally, reader proteins act as effectors in a third layer of regulation, carrying out specific functions upon methylated transcripts.

The field of epitranscriptomics still remains vastly unexplored. Future studies will need to focus on the mechanisms that define which transcripts are methylated. Moreover, as methylations are often unevenly distributed along the RNA transcript, identifying the mechanisms underlying the regional specificity of methylation, as well as which individual sites along transcripts are methylated, remain as major challenges. The methylation selectivity on particular transcripts may need to be coupled with transcription regulation. How this selectivity is determined and the interplay between methylation and transcription require further exploration. Questions regarding the effects of methyltransferases and demethylases on nuclear processing, splicing, and export also remain. Nuclear regulation of RNA methylation could play critical roles impacting biological outcomes. In particular, it will be important to determine how and why a subset of RNAs undergoes demethylation inside the nucleus, as well as the functional consequences of this required demethylation on gene expression. Interactions between the writers, readers, and erasers with other cellular components are also necessary to reveal functional roles, especially those in complex biological processes in vivo.

Abbreviations

- 2′OMe:

-

2′-O-methylation

- ALKBH5:

-

AlkB homologue 5

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- ATRA:

-

All-trans-retinoic acid

- FTO:

-

Fat-mass and obesity-associated protein

- GSC:

-

Glioblastoma stem cell

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HNRNPC:

-

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C

- lncRNA:

-

Long non-coding RNA

- m1A:

-

N 1-methyladenosine

- m5C:

-

5-methylcytidine

- METTL3:

-

Methyltransferase-like 3

- mt-tRNAMet :

-

Mitochondrial tRNA for methionine

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal RNA

- SAM:

-

S-adenosyl methionine

- Sxl :

-

Sex lethal

- YTHDC1:

-

YTH domain containing 1

- YTHDF1:

-

YTH domain family 1

- Ψ:

-

Pseudouridine

References

Volkin E, Cohn WE. Nucleoside-5′-phosphates from ribonucleic acid. Nature. 1951;167:483–4.

Cohn WE. 5-Ribosyl uracil, a carbon-carbon ribofuranosyl nucleoside in ribonucleic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;32:569–71.

Cohn WE. Pseudouridine, a carbon-carbon linked ribonucleoside in ribonucleic acids: isolation, structure, and chemical characteristics. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:1488–98.

Davis FF, Allen FW. Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1957;227:907–15.

Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:3971–5.

Dubin DT, Taylor RH. The methylation state of poly A-containing-messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975;2:1653–68.

Perry RP, Kelley DE. Existence of methylated messenger RNA in mouse L cells. Cell. 1974;1:37–42.

Wei C, Moss B. Nucleotide sequences at the N6-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1977;16:1672–6.

Camper SA, Albers RJ, Coward JK, Rottman FM. Effect of undermethylation on mRNA cytoplasmic appearance and half-life. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:538–43.

Finkel D, Groner Y. Methylations of adenosine residues (m6A) in pre-mRNA are important for formation of late simian virus 40 mRNAs. Virology. 1983;131:409–25.

He C. Grand challenge commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:863–5.

Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–7.

Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29.

Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–6.

Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–46.

Bokar JA, Rath-Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei: internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17697–704.

Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233–47.

Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–5.

Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol Cell. 2016;63:306–17.

Fustin JM, Doi M, Yamaguchi Y, Hida H, Nishimura S, Yoshida M, et al. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;155:793–806.

Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, Qu K, Zhang J, Li L, et al. m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–19.

Geula S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, Mansour AA, Kol N, Salmon-Divon M, et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002–6.

Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, Conrad NK. The U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell. 2017;169:824–35.

Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao YJ, Sun BF, et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61:507–19.

Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–4.

Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6051–63.

Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–99.

Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017;27:315–28.

Li A, Chen Y-S, Ping X-L, Yang X, Xiao W, Yang Y, et al. Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 2017;27:444–7.

Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–20.

Du H, Zhao Y, He J, Zhang Y, Xi H, Liu M, et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4–NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12626.

Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, Guo Y, Shi X, Liu Y, et al. Ythdc2 is an N6-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017;27:1115–27.

Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, Zinoviev A, Skabkin MA, Elemento O, et al. 5’ UTR m6A promotes Cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163:999–1010.

Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, Zhang X, Jaffrey SR, Qian S-B. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591–4.

Choi J, Ieong K-W, Demirci H, Chen J, Petrov A, Prabhakar A, et al. N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:110–5.

Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, Vrielink JA, Loayza-Puch F, Elkon R, Agami R. Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell. 2017;169:326–37.

Knuckles P, Carl SH, Musheev M, Niehrs C, Wenger A, Bühler M. RNA fate determination through cotranscriptional adenosine methylation and microprocessor binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:561–9.

Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, Chuan H. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–200.

Haussmann IU, Bodi Z, Sanchez-moran E, Mongan NP, Archer N, Fray RG, Soller M. m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature. 2016;540:301–4.

Lence T, Akhtar J, Bayer M, Schmid K, Spindler L, Ho CH, et al. m6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature. 2016;540:242–7.

Zhao BS, Wang X, Beadell AV, Lu Z, Shi H, Kuuspalu A, et al. m6A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature. 2017;542:475–8.

Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–8.

Abby E, Tourpin S, Ribeiro J, Daniel K, Messiaen S, Moison D, et al. Implementation of meiosis prophase I programme requires a conserved retinoid-independent stabilizer of meiotic transcripts. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10324.

Soh YQS, Mikedis MM, Kojima M, Godfrey AK, de Rooij DG, Page DC. Meioc maintains an extended meiotic prophase I in mice. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006704.

Xu K, Yang Y, Feng G-H, Sun BF, Chen JQ, Li YF, et al. Mettl3-mediated m6A regulates spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res. 2017;27:1100–4.

Li H-B, Tong J, Zhu S, Batista PJ, Duffy EE, Zhao J, et al. m6A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature. 2017;548:338–42.

Wang X, Huang N, Yang M, Wei D, Tai H, Han X, et al. FTO is required for myogenesis by positively regulating mTOR-PGC-1α pathway-mediated mitochondria biogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2702.

Li L, Zang L, Zhang F, Chen J, Shen H, Shu L, et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein regulates adult neurogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2398–411.

Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C, et al. FTO plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:127–41.

Cui Q, Shi H, Ye P, Li L, Qu Q, Sun G, et al. m6A RNA methylation regulates the self-renewal and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2622–34.

Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, Lin K, Zheng S, Lu Z, et al. m6A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:591–606.

Zhang C, Samanta D, Lu H, Bullen JW, Zhang H, Chen I, et al. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m6A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016:E2047–56.

Ma J, Yang F, Zhou C, Liu F, Yuan JH, Wang F, et al. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of HCC by modulating m6A-dependent primary miRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65:529–43.

Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62:335–45.

Bansal H, Yihua Q, Iyer SP, Ganapathy S, Proia DA, Penalva LO, et al. WTAP is a novel oncogenic protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:1171–4.

Ma Z, Morris SW, Valentine V, Li M, Herbrick JA, Cui X, et al. Fusion of two novel genes, RBM15 and MKL1, in the t(1;22)(p13;q13) of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2001;28:220–1.

Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2424–33.

Zhang W, Xu J. DNA methyltransferases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Biomark Res. 2017;5:1.

Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Nakanishi Y, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Mutation of the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 gene in human colorectal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2003;192:75–82.

Jones PA, Issa J-P, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:630–41.

Elkashef SM, Lin AP, Myers J, Sill H, Jiang D, Dahia PLM, Aguiar RCT. IDH mutation, competitive inhibition of FTO, and RNA methylation. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:619–20.

Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, et al. The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature. 2016;530:441–6.

Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, Yi C. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:311–6.

Zhou H, Kimsey IJ, Nikolova EN, Sathyamoorthy B, Grazioli G, McSally J, et al. m1A and m1G disrupt A-RNA structure through the intrinsic instability of Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:803–10.

You C, Dai X, Wang Y. Position-dependent effects of regioisomeric methylated adenine and guanine ribonucleosides on translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:9059–67.

Cenik C, Chua HN, Singh G, Akef A, Snyder MP, Palazzo AF, et al. A common class of transcripts with 5’-intron depletion, distinct early coding sequence features, and N1-methyladenosine modification. RNA. 2017;23:270–83.

Helm M, Motorin Y. Detecting RNA modifications in the epitranscriptome: predict and validate. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:275–91.

Keith JM, Ensinger MJ, Mose B. HeLa cell RNA (2’-O-methyladenosine-N6-)-methyltransferase specific for the capped 5’-end of messenger RNA. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5033–9.

Schibler U, Perry RP. The 5’-termini of heterogeneous nuclear RNA: a comparison among molecules of different sizes and ages. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4:4133–50.

Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoie A, Jiao X, Grozhik AV, Patil DP, et al. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541:371–5.

Fu Y, Jia G, Pang X, Wang RN, Wang X, Li CJ, et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1798.

Xiang Y, Laurent B, Hsu C-H, Nachtergaele S, Lu Z, Sheng W, et al. RNA m6A methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2017;543:573–6.

Molinie B, Wang J, Lim KS, Hillebrand R, Lu ZX, Van Wittenberghe N, et al. m6A-LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m6A epitranscriptome. Nat Methods. 2016;13:692–8.

Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways—2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:262–7.

Squires JE, Patel HR, Nousch M, Sibbritt T, Humphreys DT, Parker BJ, et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5023–33.

Edelheit S, Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Wurtzel O, Sorek R. Transcriptome-wide mapping of 5-methylcytidine RNA modifications in bacteria, Archaea, and yeast reveals m5C within Archaeal mRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003602.

Yang X, Yang Y, Sun B-F, Chen YS, Xu JW, Lai WY, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export—NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m5C reader. Cell Res. 2017;27:606–25.

Xu L, Liu X, Sheng N, Oo KS, Liang J, Chionh YH, et al. Three distinct 3-methylcytidine (m3C) methyltransferases modify tRNA and mRNA in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:14695–703.

Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, Shin H, Bartoli KM, Gilbert WV. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature. 2014;515:143–6.

Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Herbst RH, León-Ricardo BX, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell. 2014;159:148–62.

Lovejoy AF, Riordan DP, Brown PO. Transcriptome-wide mapping of pseudouridines: pseudouridine synthases modify specific mRNAs in S. cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110799.

Li X, Zhu P, Ma S, Song J, Bai J, Sun F, Yi C. Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:592–7.

Fernández IS, Ng CL, Kelley AC, Wu G, Yu Y-T, Ramakrishnan V. Unusual base pairing during the decoding of a stop codon by the ribosome. Nature. 2013;500:107–10.

Karijolich J, Kantartzis A, Yu Y-T. RNA modifications: a mechanism that modulates gene expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;629:1–19.

Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, Wang X, Fu Y, Wei J, et al. ALKBH1-mediated tRNA demethylation regulates translation. Cell. 2016;167:1897.

Ueda Y, Ooshio I, Fusamae Y, Kitae K, Kawaguchi M, Jingushi K, et al. AlkB homolog 3-mediated tRNA demethylation promotes protein synthesis in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42271.

Blanco S, Dietmann S, Flores JV, Hussain S, Kutter C, Humphreys P, et al. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J. 2014;33:2020–39.

Blanco S, Bandiera R, Popis M, Hussain S, Lombard P, Aleksic J, et al. Stem cell function and stress response are controlled by protein synthesis. Nature. 2016;534:335–40.

Van Haute L, Dietmann S, Kremer L, Hussain S, Pearce SF, Powell CA, et al. Deficient methylation and formylation of mt-tRNAMet wobble cytosine in a patient carrying mutations in NSUN3. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12039.

Nakano S, Suzuki T, Kawarada L, Iwata H, Asano K, Suzuki T. NSUN3 methylase initiates 5-formylcytidine biogenesis in human mitochondrial tRNAMet. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:546–51.

Haag S, Sloan KE, Ranjan N, Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Blessing C, et al. NSUN3 and ABH1 modify the wobble position of mt‐tRNAMet to expand codon recognition in mitochondrial translation. EMBO J. 2016;35:2104–19.

Long T, Li J, Li H, Zhou M, Zhou XL, Liu RJ, Wang ED. Sequence-specific and shape-selective RNA recognition by the human RNA 5-methylcytosine methyltransferase NSun. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:24293–303.

Rubio MAT, Gaston KW, McKenney KM, Fleming IM, Paris Z, Limbach PA, Alfonzo JD. Editing and methylation at a single site by functionally interdependent activities. Nature. 2017;542:494–7.

Zhou F, Liu Y, Rohde C, Pauli C, Gerloff D, Köhn M, et al. AML1-ETO requires enhanced C/D box snoRNA/RNP formation to induce self-renewal and leukaemia. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:844–55.

Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519:482–5.

Patil DP, Chen C-K, Pickering BF, Chow A, Jackson C, Guttman M, Jaffrey SR. m6A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537:369–73.

Huang L, Ashraf S, Wang J, Lilley DM. Control of box C/D snoRNP assembly by N6-methylation of adenine. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1631–45.

Ivanova I, Much C, Di Giacomo M, Azzi C, Morgan M, Moreira PN, et al. The RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 is essential for the post-transcriptional regulation of the maternal transcriptome and oocyte competence. Mol Cell. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.003.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited because of space limitations. We would like to thank members of our lab for helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

P.J.H. is supported by the NIH Medical Scientist National Research Service Award T32 GM007281. C.H. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM071440 and HG008935. C.H. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors wrote, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsu, P.J., Shi, H. & He, C. Epitranscriptomic influences on development and disease. Genome Biol 18, 197 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-017-1336-6

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-017-1336-6