Abstract

Many factors affect the microbiomes of humans, mice, and other mammals, but substantial challenges remain in determining which of these factors are of practical importance. Considering the relative effect sizes of both biological and technical covariates can help improve study design and the quality of biological conclusions. Care must be taken to avoid technical bias that can lead to incorrect biological conclusions. The presentation of quantitative effect sizes in addition to P values will improve our ability to perform meta-analysis and to evaluate potentially relevant biological effects. A better consideration of effect size and statistical power will lead to more robust biological conclusions in microbiome studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human microbiome is a virtual organ that contains >100 times as many genes as the human genome [1]. In the past 10 years, our understanding of associations between the microbiome and health has expanded greatly. Our microbial symbionts have been implicated in a broad range of conditions including: obesity [2, 3]; asthma, allergies, and autoimmune conditions [4–10]; depression (reviewed in [11, 12]) and other mental illnesses [13, 14]; neurodegeneration [15–17]; and vascular disease [18, 19]. Nevertheless, integrating this rapidly expanding literature to find general patterns is challenging because of the myriad ways in which differences are reported. For example, the term 'dysbiosis’ may reflect differences in alpha diversity (the biological diversity within a sample) [13], in beta diversity (the difference in microbial community structure between samples) [20], in the abundances of specific bacterial taxa [7, 14, 15], or any combination of these three components [4, 6]. All of these differences might reflect real kinds of dysbiosis, but studies that focus on different features are difficult to compare. Even drawing generalities from different analyses of alpha diversity can be complicated. It is well known that errors in sequencing and DNA sequence alignments can lead to substantial inflation of counts of the species apparent in a given sample [21–25]. Moreover, different measures of diversity focusing on richness (the number of kinds of entities), evenness (whether all entities in the sample have the same abundance distribution), or a combination of these can produce entirely different results than ranking samples by diversity.

Establishing consistent relationships between specific taxa and disease has been especially problematic, in part because of differences in how studies define clinical populations, handle sample preparation and DNA-sequencing methodology, and use bioinformatics tools and reference databases, all of which can affect the result substantially [26–29]. A literature search may find that the same taxon has been both positively and negatively associated with a disease state in different studies. For example, the Firmicutes to Bacteriodetes ratio was initially thought to be associated with obesity [30] and was considered a potential biomarker [31], but our recent meta-analysis showed no clear trend for this ratio across different human obesity studies [32]. Some of the problems could be technical, because differences in sample handling can change the observed ratio of these phyla [33] (although we would expect these changes to cause more issues when comparing samples between studies than when comparing those within a single study). Consequently, identifying specific microbial biomarkers that are robust across populations for obesity (although, interestingly, not for inflammatory bowel disease) remains challenging. Different diseases will likely require different approaches.

Despite problems in generalizing some findings across microbiome studies, we are beginning to understand how the effect size can help to explain differences in community profiling. In statistics, effect size is defined as a quantitative measure of the differences between two or more groups, such as a correlation coefficient between two variables or a mean difference in abundance between two groups. For example, the differences in overall microbiome composition between infants and adults are so large that they can be seen even across studies that use radically different methods [34]; this is because the relative effect size of age is larger than that of processing technique. Therefore, despite problems in generalizing findings across some microbiome studies that result from the factors noted above, we are beginning to understand how the effect sizes of specific biological and technical variables in community profiling are structured relative to others.

In this review, we argue that by explicitly considering and quantifying effect sizes in microbiome studies, we can better design experiments that limit confounding factors. This principle is well established in other fields, such as ecology [35], epidemiology (see for example [36]), and genome-wide association studies (their relationship to microbiome studies is reviewed in [37]). Avoiding important confounding variables that have a large effect size will allow researchers to more accurately and consistently draw meaningful biological conclusions from these studies of complex systems.

Biological factors that affect the microbiome

Specific consideration of effect sizes is crucial for interpreting naturally occurring biological variation in the microbiome, where the effect being investigated is frequently confounded by other factors that might affect the observed community structure. Study designs must consider the relative scale of different biological effects (for example, microbiome changes induced by diet, drugs, or disease) and technical effects (for example, the effects of PCR primers or DNA extraction methods) when selecting appropriate controls and an appropriate sample size. To date, biological factors with effects on the microbiome of varying sizes have been observed (Table 1). Consider, for example, the effect of diet on the microbiome.

Many comparative studies of mammals have shown that composition of the gut microbial community varies strongly with diet, a trait that tends to be conserved within animal taxonomic groups [38–40]. For example, in a landmark study of the gut microbiomes of major mammalian groups, Ley et al. [41] showed that diet classification explained more variation across diverse mammalian microbiomes than any other variable (although different gut physiologies are generally adapted to different diets, so separating these variables is difficult). However, a separate study of foregut and hindgut fermenting avian and ruminant species found that gut physiology explained the largest amount of gut microbiome variation [42], suggesting that diet may have been a confounding variable. More studies are now beginning to tease apart the relative effects of diet and other factors, such as taxonomy, by considering multiple animal lineages, such as panda bears and baleen whales, that have diets that diverge from those of their ancestors [43, 44].

Even within a single species, diet has been shown to shape the gut microbial community significantly. In humans, for example, changes in the gut microbiome associated with diet shifts in early development are consistent across populations, as the microbiomes of infants and toddlers systematically differ from those of adults [45, 46]. Although the microbiome continues to change over the course of a person’s life, the magnitudes of differences over time are much smaller in adults than in infants. The early differences are, in part, due to changes in diet, although it may be hard to decouple diet-specific changes from overall developmental changes. The microbiome developmental trajectory for infants may begin even before birth: the maternal gut and vaginal microbiome change during pregnancy. The gut microbiome of mothers in the third trimester, regardless of health status and diet, enters a proinflammatory configuration [47]. The vaginal microbiome has reduced diversity and a characteristic taxonomic composition during pregnancy [48, 49], which may be associated with the transfer of specific beneficial microbes to the infant. During delivery, neonates acquire microbial communities that reflect their delivery method. The undifferentiated microbial communities of vaginally delivered babies are rich in Lactobacillus, a common vaginal microbe, whereas those of infants born by cesarean are dominated by common skin microbes including Streptococcus [50].

Over the first few months of life, the infant microbiome undergoes rapid changes [46], some of which correlate with changes in breast milk composition and the breast milk microbiome [51]. Formula-fed infants also have microbial communities that are distinct from those of breastfed babies [52, 53]; formula was associated with fewer probiotic bacteria and with microbial communities closer than those of breastfed babies to the microbial communities of adults. The introduction of solid food has been associated with dramatic changes in the microbiome, during which toddlers come to more closely resemble their parents [45, 46, 52]. The compositional difference between infants and adults is larger than the differences resulting from compounded technical effects across studies [34], suggesting that this difference between human infants and adults is one of the largest effects on gut microbial community in humans.

Within children and adults, studies suggest that changes in the gut microbiome could stem from dietary changes corresponding to technological advancement, including shifts from a hunter-gatherer to an agrarian or industrialized society [45, 54]. These differences may be confounded, however, by other non-diet-related factors that co-vary with these shifts, such as exposure to antibiotics [55, 56] or the movement of industrialized individuals into confined, more sterile buildings [57]. Antibiotic-induced changes in the microbiome can last long after the course of treatment is completed [56, 58]. Although differences in microbial communities resulting from antibiotic use can be seen [56], different individuals respond differently to a single antibiotic [59]. At this scale, some technical effects, such as those associated with differences in sequencing platforms or reagent contamination, are smaller than the biological effect and can be corrected for using sequence data processing and statistical techniques. Nevertheless, compounded effects may lead to differences between studies that are larger than the biological effect being examined. It is often possible to see clear separation between communities using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) space even with cross-sectional data. PCoA provides a quick visualization technique for assessing which effects are large and which are small in terms of the degree of difference in a reduced-dimensionality space, although statistical confirmation using techniques such as ANOSIM or PERMANOVA is also necessary. Essentially, factors that led to groups of samples separating more in PCoA space have larger effects. One important caveat is that the choice of distance metric can have a large effect on this clustering [60].

On a finer scale, for example when considering only Western human populations, the effects of individual diet are less pronounced. Long-term dietary patterns, however, have been shown to alter the microbiome [61]. Several mouse models have demonstrated a mechanistic role for diet. In one study, mice were humanized with stool from lean or obese donors. Cohousing obese mice with lean mice led to weight loss only if the obese mouse was fed a high-fiber diet [2]. Another study using humanized gnotobiotic mice (that is, initially germ-free mice colonized with human-derived microbes) showed that a low-fiber diet led to a significant loss of diversity, and that the changes in the microbiome were transmitted to pups [62]. Increasing the fiber in the mouse’s diet led to an increase in microbiome diversity [62]. Nevertheless, it can be hard to separate long-term dietary patterns from other factors that shape individual microbial communities. For example, exercise is hypothesized to alter the microbiome [63–65]. One study found differences between extreme athletes and age- and weight-matched controls [64]. It is unclear, however, whether these differences are due to the strenuous training regime, the dietary requirements of the exercise program, or a combination of these two factors [63, 64]. At this scale, cross-sectional data may overlap in PCoA space.

Host genetics help to shape microbial communities. Identical twins share slightly more of their overall microbial communities than do fraternal twins [3, 66], although some taxa are far more heritable than others. Cross-sectional studies suggest that the coevolution of bacteria and human ancestors can also shape disease risk: the transfer of Helicobacter pylori strains that evolved separately from their host may confer a higher risk of gastric cancer [67]. However, separating the effect of genetics from those of vertical transmission from mother to child [52] or of transfer due to cohabitation with older children can be difficult, and the relative effect sizes of these factors is unknown [68].

Cohabitation and pet ownership modify microbial communities, and their effects can be confounded with those of diet (which is often shared within a household). Spouses are sometimes used as controls, because they are hypothesized to have similar diets. However, cohabitating couples can share more of their skin microbiomes, and to a lesser extent their gut microbiomes, than couples who do not live together [68]. Dog ownership also influences the similarity of the skin, but not fecal, microbial community [68].

Exposure to chemicals other than antibiotics also shapes our microbiome, and microbes may in turn shape our responses to these chemicals. There is mounting evidence that use of pharmaceuticals—both over-the-counter [69] and prescription [70–73]—leads to changes in microbial community structures. For example, metformin use was correlated with a change in the microbiome of Swedish and Chinese adults with type II diabetes [72]. (Notably, in this study, the failure to reproduce taxonomic biomarkers that were associated with disease in the two populations was due to different prevalence of metformin use, which has a large effect on the microbiome; the drug was used only in diabetes cases and not in healthy controls.) Changes in the microbiome may also be linked to specific side effects; for example, metformin use improved not only glucose metabolism but also pathways contributing to gas and intestinal discomfort. Which of these factors contributed most to microbiome changes is difficult to resolve with the available data [72].

Within a single individual, short-term or long-term interventions present the largest potential for remediation, but the effects of interventions often vary and methodology matters. A study that looked for a consistent change in the microbiome in response to a high- or low-fiber diet found no differences [43]. A group focusing on a mostly meat or mostly plant diet found a difference in community structure only when considering relative change in community structure, and did not find that communities from different people converged on a common state overall [74].

Technical factors affecting the microbiome

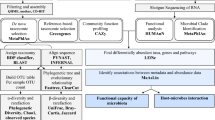

Technical sources of variation have a large influence on the observed structure of the microbial community, often on scales similar to or larger than biological effects. Considerations include sample collection and storage techniques, DNA extraction method, selection of hypervariable region and PCR primers, sequencing method, and bioinformatics analysis method (Fig. 1, Table 2).

PCoA differences in PCR primers can outweigh differences among individuals within one body site, but not the differences between different body sites. In the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) dataset, when V1-3 and V3-5 primers are combined across body sites, a the effect of PCR primers is small compared to b the effect of body site. However, if we analyze individual body sites such as c the mouth or d the mouth subsites, the effect of primer is much greater than the difference between different individuals (or even of different locations within the mouth) at that specific body site. GI gastrointestinal

An early consideration in microbiome studies is sample collection and storage. Stool samples can be collected using a bulk fecal sample or a swab from used toilet paper [75]. The gold standard for microbial storage is freezing samples at −80 °C. Recent studies suggest that long-term storage at room temperature can alter sample stability. Preservation methods such as fecal occult blood test cards, which are used in colon cancer testing [76, 77], or storage with preservatives [76] offer better alternatives. Freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided because they affect reproducibility [78]. Nevertheless, some studies have found that preservation buffers alter the observed community structure [79]. Preservation method seems to have a larger impact on observed microbial communities than collection method, although it is not sufficient to overcome inter-individual variation [76].

Sample processing plays a large role in determining the observed microbiota. DNA extraction methods vary in their yields, biases, and reproducibility [80, 81]. For example, the extraction protocols used in the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) and the European MetaHIT consortium differed in the kingdoms and phyla extracted [81]. Similarly, the DNA target fragment and primer selection can create biases. Although the V2 and V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene are better than others for broad phylogenetic classification [82], these regions often yield results that differ from each other, even when combined with mapping to a common set of full-length reference sequences. For example, all the HMP samples were sequenced using primers targeting two different hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [83]. The separation of samples in PCoA space indicates that the technical effect of different primer regions is larger than any of the biological effects within the study (Fig. 2). Finally, the choice of sequencing technology also has an effect on the observed community structure. Longer reads can improve classification accuracy [82], but only if the sequencing technology does not introduce additional errors.

PCoA patterns of technical and biological variation. Two groups (black, gray) with significantly different distances (P < 0.05) and varying effect size. a A large separation in PCoA space and large effect size. Separation in PCoA space (shown here in the first two dimensions) may be caused by technical differences in the same sample set, such as different primer regions or sequence lengths. b Clear separation in PCoA space, similar to patterns seen with large biological effects. In cross-sectional studies, age comparisons between young children and adults or comparisons between Western and nonWestern adults might follow this pattern. c Moderate biological effect. d Small biological effect. Sometimes effects can be confounded. In e the technical effect and in f the biological effect are conflated because the samples were not randomized. In g and h, there is a technical and a biological effect, but the samples were randomized among conditions, so the relative size of these effects can be measured

Choices in data processing also play a role in the biological conclusions reached in a study or set of combined studies. Read trimming may be necessary to normalize combined studies [34], but shorter reads can affect the accuracy of taxonomic classifications [82]. The selection of a method to map sequences into microbes has a large impact on the microbial communities identified. Several approaches exist, but clustering of sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) on the basis of some threshold is common. Sequences may be clustered against themselves [22, 84], clustered against a reference [84], or clustered against a combination of the two [85]. The selection of a particular OTU clustering method and OTU clustering algorithm alters the observed microbial community and can artificially inflate the number of OTUs observed [22, 84]. De-noising (a technique commonly used with 454 sequencing [22]), removal of chimeric sequences generated during PCR [86, 87], and quality filtering of Illumina data can help to alleviate some of these problems [24, 88]. After OTU picking, the selection of biological criteria, ecological metric, and statistical test can lead to different biological conclusions [60, 89].

The degree to which technical variation impacts biological conclusions depends on the relative scale of the effects and the method of comparison. For very large effects, biologically relevant patterns may be reproducible when studies are combined even though there is technical variability. A comparison of fecal and oral communities in adult humans may be robust to multiple technical effects, such as differences in extraction method, PCR primers, and sequencing technology (Fig. 2). Conversely, subtle biological effects can quickly become swamped. Many biological effects of interest to current research have a smaller effect on observed microbial communities than the technical variations commonly observed among studies [32, 34].

Failure to consider technical variation can also confound biological interpretation. In low-biomass samples, technical confounders such as reagent contamination can have larger effects than the biological signal. A longitudinal study of nasopharyngeal samples from young children [90] exemplified this effect. Principal Coordinates Analysis of the data found a sharp distinction by age. It was later determined, however, that the samples had been extracted with reagents from two different lots—the differences in the microbial communities were due to reagent contamination and not biological differences [91]. Higher biomass samples are not immune to this problem. Extraction of case and control samples using two different protocols could potentially lead to similar erroneous conclusions.

Comparing effects: the importance of large integrated studies

Large-scale integration provides a common framework for comparing effects. Studies of large populations are often successful in capturing the significance of biological patterns such as age [45], human microbiome composition [75, 92], or specific health conditions such as Crohn’s disease [93]. The scale of the population means that multiple effects can also be compared across the same set of samples. For example, the HMP provided a reference map of microbial diversity found in the body of Western adults [92]. Yatsunenko et al. [45] highlight the effect of age over other factors including weight and country of origin, demonstrating that age has a larger effect on the microbiome than nationality, which in turn has a larger effect than weight (Fig. 3). Two recently published studies of Belgian and Dutch populations provide very interesting examples of what can be achieved through larger population-based studies, especially in terms of understanding which factors are important in structuring the microbiome.

Relative effect sizes of biological covariates on the human microbiome. Principal coordinates projection of unweighted UniFrac distance, using data from Yatsunenko et al. [45], shows a age (blue gradient; missing samples in red) separating the data along the first axis and b country (USA, orange; Malawi, green; Venezuela, purple) separating the data along the second principal coordinates axis. c Body mass index in adults has a much more subtle effect, and does not separate along any of the first three principal coordinate axes (normal, red; overweight, green; obese, blue; missing samples, gray)

The LL-Deep study, which used both 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing on a cohort of 1135 Dutch individuals, associated 110 host factors to 125 microbial species identified by shotgun metagenomics. In particular, this study found that age, stool frequency, dietary variables such as total carbohydrates, plants and fruits, and fizzy drinks (both 'diet' brands and those with sugar) had large effects, as did drugs such as proton pump inhibitors, statins, and antibiotics [94]. Interestingly, the authors observed 90 % concordance in associations between the shotgun metagenomic and the rRNA amplicon results, suggesting that many conclusions about important microbiome effects may be robust to some kinds of methodological variation, even if the absolute level of specific taxa are not. The Flemish Gut Flora Project, which used 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing on a cohort of 1106 individuals, identified 69 variables relating to the subjects that correlated with the microbiome, including use of 13 drugs ranging from antibiotics to antidepressants, and explained 7.7 % of the variation in the microbiome. The consistency of the stool (which is a proxy for transit time), age, and body mass index were especially influential, as was the frequency of fruit in the diet; the adult subjects did not show effects of early-life variables such as delivery mode or residence type during early childhood [95]. The American Gut Project (www.americangut.org), now with over 10,000 samples processed, is a crowd-sourced microbiome study that expands on the effects considered by the HMP to evaluate microbial diversity across Western populations with fewer restrictions on health and lifestyle. Large-scale studies have two advantages for comparisons. They can help to limit technical variability because samples within the same study are collected and processed in the same way. This reduces technical confounders, making it easier to draw biological conclusions. Second, large population studies increase the probability of finding subtle biological effects which may be lost in the noise of smaller studies.

Meta-analyses that place smaller studies into the context of these larger studies can also provide new insights into the relative size of the changes seen in the smaller studies [34]. Weingarden et al. [96] took advantage of the HMP and contextualized the dynamics of fecal material transplants (FMT). Their initial data set focused on a time series from four patients who had recurrent Clostridium difficile infection and a healthy donor. By combining the time series results with a larger dataset, they revealed the dramatic restoration that diseased patients undergo after the transplant is administered, ultimately helping the patients recover from the severe C. difficile infection [96, 97].

When conducting a meta-analysis, however, it is important to consider whether the differences in microbial communities in different studies are due to technical or biological effects. Selecting studies that each include biologically relevant controls can help to determine whether the scale of the effect between the studies results from a biological or a technical covariate. In the FMT study [96], the donor (control) sample clustered with the HMP fecal samples, while the pre-treatment recipients did not. Had the donor point grouped somewhere else, perhaps among the skin samples or in a completely separate location, it could have indicated a large technical effect, suggesting that the studies should not be combined into a single PCoA (although trends might still be identified within each study and compared). Similarly, a study of the progression of the microbiome of an infant during the first 2 years of life showed changes in the infant microbiome with age [36], but it was only when this study was placed in the context of the HMP that the scale of developmental change within a single infant body site relative to differences in the microbiome among distinct human body sites became clear [34].

Leveraging effect size in meta-analysis

Compared to other fields, meta-analysis among microbiome studies is still in its infancy. Statistical methods can help to overcome the complication of technical effects in direct comparisons, allowing focus on the biological results. Medical drug trials [98, 99] routinely report quantified effect sizes. This practice has several advantages. First, it moves away from a common binary paradigm of not significant or significant at P < 0.05 [35]. The combination of significance and effect size can be important for avoiding undue alarm, as has been shown in other fields. For instance, a recent meta-analysis found a statistically significant increase in cancer risk associated with red meat consumption [100]. The relative risk of colon cancer associated with meat consumption is, however, much lower than the relative risk of colon cancer associated with an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) diagnosis. With a P value alone, it might not have been possible to determine which factor had a larger impact on cancer risk. Effect size quantification may also help to capture the range of variation in effects across different populations: there are probably multiple ways for a microbial community to be 'sick', rather than single set of taxa that are enriched or depleted in perturbed populations. We see this, for example, in the different 'obese' microbiomes that seem to characterize different populations of obese individuals. Finally, effect size is also closely linked to statistical power, or the number of samples needed to reveal a statistical difference. Quantitative power estimates could improve experimental design and limit publication bias [35].

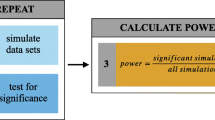

Unfortunately, effect size and statistical power are challenging to calculate in microbiome data. Currently, applied power calculations (reviewed in [35]) typically make assumptions about the data that do not hold true in the analysis of microbial communities (Box 1). Some solutions to this problem have been proposed, including the Dirichlet Multinomial method [101] and random forest analysis [102] for OTUs, a simulation-based method for PERMANOVA-based beta diversity comparisons [103], and power estimation by subsampling (Box 1). Nevertheless, power analysis remains rare in microbiome studies. New methods could facilitate better understanding of effect sizes. As the scope of microbiome research continues to expand to include metabolomic, metagenomics, and metatranscriptomic data, effect size considerations will only become more important.

Considerations for study design

Large-scale studies provide insight into which variables have broad effects on the microbiome, but they are not always feasible. Small, well-designed studies that address hypotheses of limited scope have a large potential to advance the field. In designing one of these studies, it is better to define a population of interest narrowly, rather than trying to draw general conclusions. The design and implementation of small studies should strive for four goals: limited focus, rich metadata collection, appropriate sample size, and minimized technical variation.

Limiting the scope of the study increases the probability that a small study will be successful because it decreases noise and confounding factors. For example, the hypothesis 'milk consumption alters the microbial community structure and richness in children' might be better phrased as 'milk consumption affects the microbial community structure and richness in children in third through fifth grade attending New York Public schools'. Additionally, the study should define exclusion criteria; for example, perhaps children who have taken antibiotics in the past 6 months or 1 year should be excluded [56, 58]. Broader hypotheses may be better tackled in meta-analyses, where multiple small, well-designed studies on a similar topic can be combined.

Information about factors that might influence the microbiome should be included in sample collection. For example, the study of children attending New York City Public Schools might not have birth delivery method as an exclusion criterion, but whether the child was born by C-section or vaginally could influence their microbial community, so this information should be recorded and analyzed. Self-reported data should be obtained using a controlled vocabulary and common units. If multiple small studies are planned, standard metadata collection will minimize time in meta-analysis.

A second consideration in defining scope is to identify a target sample size. Other studies may be used as a guide, particularly if the data can be used to quantify an effect size. Quantitative power calculations (Box 1) can be particularly helpful in defining a sample size. Nevertheless, this comparison should be done judiciously. Sample sizes should be estimated by selecting a known effect that is expected to be of similar scale. It may be prudent to consider the phenotype associated with the effect, and whether the effect might directly target microbes. For example, one might guess that a new drug that inhibits folate metabolism, which is involved in DNA repair in bacteria and eukaryotes, might have an effect close to those of other drugs that are genotoxic, such as specific classes of antibiotics and anticancer agents.

Technical variation within a study should be minimized. Sample collection and storage should be standardized. Studies in which samples cannot be frozen within a day of collection should consider a preservation method, although even preserved samples should be frozen at −80 °C for long-term storage [76, 77]. If possible, samples should be processed together using the same reagents. If this is not possible because of the size of the study, samples should be randomized to minimize the confounding of technical and biological variables [91]. The use of standard processing pipelines, like those described by the Earth Microbiome Project [104, 105], may facilitate data aggregation for meta-analyses. Participation in standardization efforts, such as the Microbiome Quality Control Project (http://www.mbqc.org/) and the Unified Microbiome Initiative [106], can help to identify sources of lab-to-lab variation.

Conclusions

Microbiome research is rapidly advancing, although several challenges that have been tackled in other fields, including epidemiology, ecology, and human genetic studies (in particular, genome-wide association studies), need to be addressed fully. First, technical variation still makes it difficult to compare claimed effect sizes, or claimed associations of particular taxa with particular phenotypes. Standardized methods, including bioinformatics protocols, will help immensely here. This is particularly an issue for translational studies between humans and animal models, because it can be difficult to determine whether differences in microbial communities or host responses to these changes are due to differences in the host physiology or variation in the variable of interest. However, the potential payoff for translation of microbiome results from high-throughput animal models, such as flies or zebrafish, to humans, is enormous.

In this review, we have focused mainly on 16S rRNA amplicon analysis and shotgun metagenomic studies because these are most prevalent in the literature at present. However, microbiome studies are continuing to expand, such that a single study can include multi-omics techniques such as metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics. Before we embark too far on the exploration of multiomics datasets, methods standardization across multiple platforms will be necessary to facilitate robust biological conclusions, despite the considerable cost of such standardization efforts.

Overall, the field is converging on many conclusions about what does and does not matter in the microbiome: improved standards and methodologies will greatly accelerate our ability to integrate and trust new discoveries.

Abbreviations

- FMT:

-

Fecal material transplants

- HMP:

-

Human microbiome project

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinates analysis

References

Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–9.

Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214.

Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159:789–99.

Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Wise P, Zhang Y, Hobson SA, Garcia Lloret M, et al. A microbiota signature associated with experimental food allergy promotes allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:201–12.

Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyötyläinen T, Hämäläinen A-M, et al. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:260–73.

Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, Feng Q, Wang D, Liang D, et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med. 2015;21:895–905.

Costello M-E, Ciccia F, Willner D, Warrington N, Robinson PC, Gardiner B, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, doi:10.1002/art.38967.

de Goffau MC, Luopajärvi K, Knip M, Ilonen J, Ruohtula T, Härkönen T, et al. Fecal microbiota composition differs between children with β-cell autoimmunity and those without. Diabetes. 2013;62:1238–44.

Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Novelo LL, Casella G, et al. Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. ISME J. 2011;5:82–91.

Michail S, Durbin M, Turner D, Griffiths AM, Mack DR, Hyams J, et al. Alterations in the gut microbiome of children with severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1799–808.

Luna RA, Foster JA. Gut brain axis: diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;32:35–41.

Dash S, Clarke G, Berk M, Jacka FN. The gut microbiome and diet in psychiatry: focus on depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:1–6.

Kleiman SC, Watson HJ, Bulik-Sullivan EC, Huh EY, Tarantino LM, Bulik CM, Carroll IM. The intestinal microbiota in acute anorexia nervosa and during renourishment: relationship to depression, anxiety, and eating disorder psychopathology. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:969–81.

Castro-Nallar E, Bendall ML, Pérez-Losada M, Sabuncyan S, Severance EG, Dickerson FB, et al. Composition, taxonomy and functional diversity of the oropharynx microbiome in individuals with schizophrenia and controls. PeerJ. 2015;3, e1140.

Keshavarzian A, Green SJ, Engen PA, Voigt RM, Naqib A, Forsyth CB, et al. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1351–60.

Hill JM, Clement C, Pogue AI, Bhattacharjee S, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. Pathogenic microbes, the microbiome, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:127.

Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. Microbiome-generated amyloid and potential impact on amyloidogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). J Nat Sci. 2015;1, e138.

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63.

Tang WHW, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–84.

Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Engen PA, et al. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G966–78.

Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:38.

Koskinen K, Auvinen P, Björkroth KJ, Hultman J. Inconsistent denoising and clustering algorithms for amplicon sequence data. J Comput Biol. 2015;22:743–51.

Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P. Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Env Microbiol. 2010;12:118–23.

Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–8.

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3.

Barb JJ, Oler AJ, Kim H-S, Chalmers N, Wallen GR, Cashion A, et al. Development of an analysis pipeline characterizing multiple hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA using mock samples. PLoS One. 2016;11, e0148047.

Liu Z, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. Accurate taxonomy assignments from 16S rRNA sequences produced by highly parallel pyrosequencers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36, e120.

Lee S, Sung J, Lee J, Ko G. Comparison of the gut microbiotas of healthy adult twins living in South Korea and the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7433–7.

Kemppainen KM, Ardissone AN, Davis-Richardson AG, Fagen JR, Gano KA, León-Novelo LG, et al. Early childhood gut microbiomes show strong geographic differences among subjects at high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:329–32.

Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Gordon JI. Gut microbiome as a biomarker and therapeutic target for treating obesity or an obesity related disorder. Patent Application Publication 2010. US 2010/0172874 A1.

Walters WA, Xu Z, Knight R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4223–33.

Bahl MI, Bergström A, Licht TR. Freezing fecal samples prior to DNA extraction affects the firmicutes to bacteroidetes ratio determined by downstream quantitative PCR analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;329:193–7.

Lozupone CA, Stombaugh J, Gonzalez A, Ackermann G, Wendel D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, et al. Meta-analyses of studies of the human microbiota. Genome Res. 2013;23:1704–14.

Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007;82:591–605.

Bauman A, Sallis J, Dzewaltowski D, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(2 Suppl):5–14.

Gilbert JA, Quinn RA, Debelius J, Xu ZZ, Morton J, Garg N, et al. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature. 2016;535:94–103.

Phillips CD, Phelan G, Dowd SE, McDonough MM, Ferguson AW, Delton Hanson J, et al. Microbiome analysis among bats describes influences of host phylogeny, life history, physiology and geography. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:2617–27.

Ochman H, Worobey M, Kuo C-H, Ndjango J-BN, Peeters M, Hahn BH, Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary relationships of wild hominids recapitulated by gut microbial communities. PLoS Biol. 2010;8, e1000546.

McCord AI, Chapman CA, Weny G, Tumukunde A, Hyeroba D, Klotz K, et al. Fecal microbiomes of non-human primates in Western Uganda reveal species-specific communities largely resistant to habitat perturbation. Am J Primatol. 2014;76:347–54.

Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:776–88.

Godoy-Vitorino F, Goldfarb KC, Karaoz U, Leal S, Garcia-Amado MA, Hugenholtz P, et al. Comparative analyses of foregut and hindgut bacterial communities in hoatzins and cows. ISME J. 2012;6:531–41.

Sanders JG, Beichman AC, Roman J, Scott JJ, Emerson D, McCarthy JJ, Girguis PR. Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8285.

Zhu L, Wu Q, Dai J, Zhang S, Wei F. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17714–9.

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–7.

Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl):4578–85.

Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150:470–80.

Aagaard K, Riehle K, Ma J, Segata N, Mistretta T-A, Coarfa C, et al. A metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2012;7, e36466.

MacIntyre DA, Chandiramani M, Lee YS, Kindinger L, Smith A, Angelopoulos N, et al. The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a European population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8988.

Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11971–5.

Cabrera-Rubio R, Collado MC, Laitinen K, Salminen S, Isolauri E, Mira A. The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:544–51.

Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:852.

Harmsen HJ, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Raangs GC, Wagendorp AA, Klijn N, Bindels JG, Welling GW. Analysis of intestinal flora development in breast-fed and formula-fed infants by using molecular identification and detection methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:61–7.

Clemente JC, Pehrsson EC, Blaser MJ, Sandhu K, Gao Z, Wang B, et al. The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians. Sci Adv. 2015;1, e1500183.

Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–6.

Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, Bork P, de Vos WM. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10410.

Lax S, Smith DP, Hampton-Marcell J, Owens SM, Handley KM, Scott NM, et al. Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science. 2014;345:1048–52.

Jakobsson HE, Jernberg C, Andersson AF, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. Short-term antibiotic treatment has differing long-term impacts on the human throat and gut microbiome. PLoS One. 2010;5, e9836.

Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl):4554–61.

Kuczynski J, Liu Z, Lozupone C, McDonald D, Fierer N, Knight R. Microbial community resemblance methods differ in their ability to detect biologically relevant patterns. Nat Methods. 2010;7:813–9.

Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen Y-Y, Keilbaugh SA, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–8.

Sonnenburg ED, Smits SA, Tikhonov M, Higginbottom SK, Wingreen NS, Sonnenburg JL. Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature. 2016;529:212–5.

Kang SS, Jeraldo PR, Kurti A, Miller ME, Cook MD, Whitlock K, et al. Diet and exercise orthogonally alter the gut microbiome and reveal independent associations with anxiety and cognition. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:36.

Clarke SF, Murphy EF, O’Sullivan O, Lucey AJ, Humphreys M, Hogan A, et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut. 2014;63:1913–20.

Lambert JE, Myslicki JP, Bomhof MR, Belke DD, Shearer J, Reimer RA. Exercise training modifies gut microbiota in normal and diabetic mice. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40:749–52.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4.

Kodaman N, Pazos A, Schneider BG, Piazuelo MB, Mera R, Sobota RS, et al. Human and Helicobacter pylori coevolution shapes the risk of gastric disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1455–60.

Song SJ, Lauber C, Costello EK, Lozupone CA, Humphrey G, Berg-Lyons D, et al. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. Elife. 2013;2, e00458.

Maurice CF, Haiser HJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Xenobiotics shape the physiology and gene expression of the active human gut microbiome. Cell. 2013;152:39–50.

Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan M-E, Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Poole AC, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65:749–56.

Freedberg DE, Toussaint NC, Chen SP, Ratner AJ, Whittier S, Wang TC, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter specific taxa in the human gastrointestinal microbiome: a crossover trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:883–5.

Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, Falony G, Le Chatelier E, Sunagawa S, et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:262–6.

Rooks MG, Veiga P, Wardwell-Scott LH, Tickle T, Segata N, Michaud M, et al. Gut microbiome composition and function in experimental colitis during active disease and treatment-induced remission. ISME J. 2014;8:1403–17.

David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–63.

Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science. 2009;326:1694–7.

Sinha R, Chen J, Amir A, Vogtmann E, Shi J, Inman KS, et al. Collecting fecal samples for microbiome analyses in epidemiology studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:407–16.

Dominianni C, Wu J, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Comparison of methods for fecal microbiome biospecimen collection. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:103.

Cuthbertson L, Rogers GB, Walker AW, Oliver A, Hoffman LR, Carroll MP, et al. Implications of multiple freeze-thawing on respiratory samples for culture-independent analyses. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14:464–7.

Gorzelak MA, Gill SK, Tasnim N, Ahmadi-Vand Z, Jay M, Gibson DL. Methods for improving human gut microbiome data by reducing variability through sample processing and storage of stool. PLoS One. 2015;10, e0134802.

Yuan S, Cohen DB, Ravel J, Abdo Z, Forney LJ. Evaluation of methods for the extraction and purification of DNA from the human microbiome. PLoS One. 2012;7, e33865.

Wesolowska-Andersen A, Bahl MI, Carvalho V, Kristiansen K, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Gupta R, Licht TR. Choice of bacterial DNA extraction method from fecal material influences community structure as evaluated by metagenomic analysis. Microbiome. 2014;2:19.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–7.

Jumpstart Consortium Human Microbiome Project Data Generation Working Group. Evaluation of 16S rDNA-based community profiling for human microbiome research. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39315.

Navas-Molina JA, Peralta-Sánchez JM, González A, McMurdie PJ, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Xu Z, et al. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol. 2013;531:371–444.

Rideout JR, He Y, Navas-Molina JA, Walters WA, Ursell LK, Gibbons SM, et al. Subsampled open-reference clustering creates consistent, comprehensive OTU definitions and scales to billions of sequences. PeerJ. 2014;2, e545.

Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504.

Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–200.

Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:57–9.

Mandal S, Van Treuren W, White RA, Eggesbø M, Knight R, Peddada SD. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:27663.

Turner P, Turner C, Jankhot A, Helen N, Lee SJ, Day NP, et al. A longitudinal study of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in a cohort of infants and their mothers on the Thailand-Myanmar border. PLoS One. 2012;7, e38271.

Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, Calus ST, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF, et al. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol. 2014;12:87.

Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Knight R, Abubucker S, Badger JH, Chinwalla AT, et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2013;486:207–14.

Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:382–92.

Zhernakova A, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, Tigchelaar EF, Schirmer M, Vatanen T, et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science. 2016;352:565–9.

Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Darzi Y, Faust K, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science. 2016;352:560–4.

Weingarden A, González A, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Weiss S, Humphry G, Berg-Lyons D, et al. Dynamic changes in short- and long-term bacterial composition following fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Microbiome. 2015;3:10.

Gut Ecosystem Restoration via Fecal Transplantation [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=−FFDqhM4pks]. Accessed 17 Oct 2016.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Onkologie. 2000;23:597–602.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg. 2012;10:28–55.

Johnson CM, Wei C, Ensor JE, Smolenski DJ, Amos CI, Levin B, Berry DA. Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1207–22.

La Rosa PS, Brooks JP, Deych E, Boone EL, Edwards DJ, Wang Q, et al. Hypothesis testing and power calculations for taxonomic-based human microbiome data. PLoS One. 2012;7, e52078.

Knights D, Costello EK, Knight R. Supervised classification of human microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:343–59.

Kelly BJ, Gross R, Bittinger K, Sherrill-Mix S, Lewis JD, Collman RG, et al. Power and sample-size estimation for microbiome studies using pairwise distances and PERMANOVA. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2461–8.

Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R. The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biol. 2014;12:69.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl):4516–22.

Alivisatos AP, Blaser MJ, Brodie EL, Chun M, Dangl JL, Donohue TJ, et al. A unified initiative to harness Earth’s microbiomes. Science. 2015;350:507–8.

Weiss SJ, Xu Z, Amir A, Peddada S, Bittinger K, Gonzalez A, et al. Effects of library size variance, sparsity, and compositionality on the analysis of microbiome data. PeerJ Preprints. 2015;3, e1408.

Cramér H. Mathematical methods of statistics. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1946.

Liu XS. Statistical power analysis for the social and behavioral sciences: basic and advanced techniques. New York: Routledge; 2014.

Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46.

Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral Ecol. 1993;18:117–43.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Amnon Amir and Jon Sanders for their help during the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America, the National Institutes of Health, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

JD and RK outlined the manuscript; JD, SJS, YVB, ZZX, AG and RK drafted, read and reviewed the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Debelius, J., Song, S.J., Vazquez-Baeza, Y. et al. Tiny microbes, enormous impacts: what matters in gut microbiome studies?. Genome Biol 17, 217 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1086-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1086-x