Abstract

Background

Timely management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and acute stroke has undergone impressive progress during the last decade. However, it is currently unknown whether both sexes have profited equally from improved strategies. We sought to analyze sex-specific temporal trends in intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality in younger patients presenting with AMI or stroke in Switzerland.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of temporal trends in 16,954 younger patients aged 18 to ≤ 52 years with AMI or acute stroke admitted to Swiss ICUs between 01/2008 and 12/2019.

Results

Over a period of 12 years, ICU admissions for AMI decreased more in women than in men (− 6.4% in women versus − 4.5% in men, p < 0.001), while ICU mortality for AMI significantly increased in women (OR 1.2 [1.10–1.30], p = 0.032), but remained unchanged in men (OR 0.99 [0.94–1.03], p = 0.71). In stroke patients, ICU admission rates increased between 3.6 and 4.1% per year in both sexes, while ICU mortality tended to decrease only in women (OR 0.91 [0.85–0.95, p = 0.057], but remained essentially unaltered in men (OR 0.99 [0.94–1.03], p = 0.75). Interventions aimed at restoring tissue perfusion were more often performed in men with AMI, while no sex difference was noted in neurovascular interventions.

Conclusion

Sex and gender disparities in disease management and outcomes persist in the era of modern interventional neurology and cardiology with opposite trends observed in younger stroke and AMI patients admitted to intensive care. Although our study has several limitations, our data suggest that management and selection criteria for ICU admission, particularly in younger women with AMI, should be carefully reassessed.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite major therapeutic advances during the last decade, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are still among the leading causes of death and serious long-term disability worldwide [1, 2]. While overall incidence and case fatality rates for stroke or acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have steadily declined since the 1980s owing to improved primary and secondary prevention and technical refinement [3, 4], concerns about different trends in diagnostics, treatment and outcome in women and men still remain. In fact, while overall stroke incidence has decreased over the last decade [3, 5,6,7], recent studies report increasing stroke incidence and case fatality rates in younger individuals [8,9,10] with inconsistent data being reported about gender differences in terms of stroke interventions, outcome and care [7, 11, 12].

A rising incidence and case fatality for AMI have been observed in younger women, but not in men [13,14,15]. Moreover, in younger men, the incidence rate of hospitalization and excess mortality has even decreased over time [4, 16]. Although exact mechanisms accounting for these differential time trends in younger women and men are lacking, an increase in comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors, in particular smoking, gender differences in clinical presentation and, thus, treatment delays have been proposed to account for this finding [14, 17, 18]. Besides differences in therapeutic options and shifts in the distribution of traditional and non-traditional risk factors over time, gender inequality in the provision of resources and structural bias may impact cardio- and neurovascular disease outcomes in the younger population [19]. We therefore sought to analyze gender-specific temporal trends in intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality over a period of 12 years (2008–2019) in younger patients aged 18–52 years presenting with AMI or ischemic stroke to Swiss hospitals.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Swiss ICU-registry (MDSi - Minimal Dataset for ICUs) of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SSICM), which contains data from all 86 certified ICUs in Switzerland as previously described [19, 20]. ICU admissions and mortality for patients with AMI or ischemic stroke were obtained from the MDSi database. Data of all patients identified with AMI or ischemic stroke in all Swiss hospitals were provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). The Ethics committee of Northwestern Switzerland approved this procedure (EKNZ UBE-15/47). The study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. We adhered to the STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies (Additional file 1: Table S1) [21].

Variables and outcomes

The primary outcome measure of this study was the temporal change in ICU mortality over 12 years. Secondary outcome measures included ICU admission rates and disease severity over time. From the MDSi dataset, we extracted demographic data including sex, age, year of admission, information about residence prior to ICU admission, admission diagnosis, therapeutic (including invasive) interventions before ICU admission, the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) [22], the Nine Equivalents of Nursing Manpower Use Score (NEMS) [23] of the first nursing shift and average NEMS per shift, as well as ICU mortality for patients who were admitted for AMI or stroke between 2008 and 2019 to an ICU in Switzerland. The selection of ischemic stroke patients was made based on the overlapping pathogenesis and risk factors of AMI and ischemic stroke and the provision of a large, uniform patient population. The SAPS II score estimates disease severity and, thus, mortality in patients admitted to the ICU. For score calculation, the worst physiological values as indicators of organ function, age, type of admission and information on previous health status (chronic diseases such as cancer, metastatic carcinoma, or hematologic malignancies) are collected within the first 24 h of ICU admission. While the SAPS II score reflects the situation at ICU admission (first 24 h), the NEMS parameters are recorded daily (per shift) until ICU discharge. Assessments include the daily amount of organ support measures (vasoactive medications, mechanical ventilation and breathing aids, renal replacement therapy), interventions during ICU stay inside (e.g., endotracheal intubation, placement of a pacemaker, cardioversion, endoscopy) and outside the ICU (e.g., surgical intervention or diagnostic procedures).

From the FSO, mortality data and diagnoses of the same period were obtained as for the MDSi dataset. Overall mortality was defined as in-hospital deaths of all patients admitted to Swiss hospitals. Younger age was defined as age ≤ 52 years. This age cutoff was based on the average menopausal age for women in Switzerland [24] to form a premenopausal female cohort and on previous studies with younger age ranging from ≤ 44 to 55 years [9,10,11,12,13,14, 25]. ICU mortality was defined as all-cause mortality during ICU stay.

Statistical analysis

Data from the MDSi database were filtered for primary admission diagnosis of AMI or ischemic stroke and patients aged > 18 and ≤ 52 years. For the numbers of total admissions and deaths, Poisson models were built for primary trend analysis, which included sex and year of admission as covariates. Data from the FSO on death numbers for the respective diagnosis per sex and age > 18 and ≤ 52 years were analyzed in parallel as surrogates of overall mortality development. Analysis of mortality (deaths per admission) was performed with a logistic model including all possible covariates from the SGI data set. Variable reduction on the logistic model was performed both stepwise and using a penalized regression (LASSO). Both reduction strategies resulted in selection of SAPS and NEMS scores as the most important explanatory variables. For both explanatory variables, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for death prediction was analyzed, and the best predictive score as defined by Youden's index [26] was analyzed for yearly trend. Baseline characteristics of the ICU population were compared between men and women using t-test, parametric rank sum test, or Chi-square test as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.6.1 with the packages glmnet, ROCit, and quantreg [27].

Results

From January 2008 to December 2019, a total of 292,103 individuals were diagnosed with either an acute stroke (n = 215,397) or an AMI (n = 270,768) in Switzerland. Among individuals aged > 18 and ≤ 52 years, 34,024 were diagnosed with AMI (5293 women, 15.6%) and 18,043 (6774 women, 37.5%) with stroke.

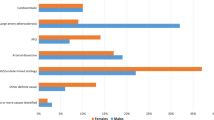

Baseline characteristics, ICU admission and mortality temporal trends in ICU patients with AMI

Over the 12-year period, 13´449 [16.6% women] individuals > 18 and ≤ 52 years were admitted to an ICU for AMI. No significant age difference was observed between women and men (45 ± 6 vs 45 ± 5 years old, p = 0.229). There was no significant sex difference in SAPS II, while the initial NEMS after admission (17.8 ± 8.0 vs 17.1 ± 7.7 points, p < 0.001) and the average NEMS per shift (16.8 ± 6.4 vs 16.3 ± 6.6 points, p < 0.001) were higher in men than in women. Lengths of ICU stay (LOS) and the absolute number of deaths over the whole period were similar between women and men. Prior to ICU admission, men with AMI underwent more frequently cardiovascular interventions (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]: 6222 [55.5%] in men vs 1081 [48.5%] in women, p < 0.001; CABG surgery: 987 [8.8%] in men vs 106 [4.75%] in women, p < 0.001). In general, men received more subsequent interventions during ICU stay (intubation, cardioversion, endoscopies) (622[5.54%] in men vs 148 [6.63%] in women, p = 0.049), more organ support such as mechanical ventilation (1330 [11.9%] in men vs 185 [8.3%] in women, p < 0.001) and vasoactive support (2520 [22.5%] in men vs 437 [19.6%] in women, p = 0.003). Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics of the ICU study population.

In Switzerland, the overall mortality rate for AMI decreased by − 3.8 to − 6.3% per year between 2008 and 2019 in both sexes. Conversely, ICU mortality rates in younger women with AMI, but not in age-matched men, have increased over time (women: OR 1.2 [1.10–1.30], p = 0.032; men: (OR 0.99 [0.94–1.03], p = 0.71, Fig. 1). Contemporaneously, ICU admission rates for younger women have declined by − 6.4% per year (−[5.8–7% per year], p < 0.001) but significantly less so in men (− 4.5% [4.2–4.8%], p < 0.001; p = 0.002 for women vs men, Fig. 2A). Disease severity as indicated by SAPS II in patients with AMI admitted to the ICU has increased over time (OR 1.05 [1.02–1.08], p < 0.001) in both sexes, while NEMS, an indicator of nursing workload, has declined (OR 0.96 [0.95–0.97], p = 0.007, Fig. 3A). When ICU mortality trends over time were adjusted for SAPS II and NEMS, mortality changes were no longer evident.

A Time trends of overall mortality, ICU mortality, and ICU admission in patients with acute myocardial infarction. B Time trends of overall mortality (no statistically significant change over time), ICU mortality (no statistically significant change over time, but tendency toward decline in women), and ICU admission in patients with ischemic stroke. Data are presented as observed numbers of patients in each year, with dotted lines representing overall patients admitted to the ICU, dashed lines showing overall deaths reported to the FSO, and continuous lines showing deaths reported in the ICU. FSO, Swiss Federal Statistical Office; ICU, intensive care unit

A Time trends of disease severity estimated by SAPS II and nursing workload estimated by NEMS in ICU patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction. B Time trends of disease severity estimated by SAPS II and nursing workload estimated by NEMS in ICU patients admitted with ischemic stroke. ICU, intensive care unit; NEMS, Nine Equivalents of Nursing Manpower Use Score; SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II. Data are presented as fraction of ICU patients at or above the threshold for the respective score (SAPS ≥ 39 or NEMS ≥ 21)

Baseline characteristics, ICU admission and mortality temporal trends in ICU patients with acute stroke

From 2008 to 2019, 3505 [39.6% women] patients aged > 18 and ≤ 52 years were admitted to ICU for stroke. Women with stroke were younger as compared to men (41 ± 9 vs 44 ± 7 years old, p < 0.001). No sex differences in NEMS and SAPS II were observed in stroke patients directly after admission (17.8 ± 9.0 points in men vs 17.6 ± 8.8 points in women, p = 0.542) and during ICU stay. No significant differences in the LOS and the absolute number of deaths over the whole period were observed between women and men. No sex differences before ICU admission were observed regarding neurovascular interventions in patients with stroke (312 [14.7%] in men vs 199 [14.3%] in women, p = 0.485). Interventions during ICU stay (endoscopy, intubation, cardioversion, diagnostic procedures, or subsequent surgeries) were similar in men and women as were organ support measures including mechanical ventilation (425 [20.1%] in men vs 248 [17.9%] in women, p = 0.111) and vasoactive support (595 [28.1%] in men vs 395 [28.4%] in women, p = 0.868). Noninvasive respiratory support was more frequently used in men (1078 [51.0%] vs 632 [45.5%] in women, p = 0.002). Table 1 depicts the baseline characteristics of the ICU study population.

Overall mortality rates for stroke in Switzerland did not show a significant time trend between 2008 and 2019 in either sex. ICU mortality rates in patients with stroke showed a trend toward a yearly decline of − 4.1% in women (OR 0.91 [0.85–0.95], p = 0.057), but remained unchanged in men (OR 0.99 [0.94–1.03] p = 0.75, Fig. 4). ICU admission rates for stroke increased over the study period in both sexes by + 3.6 to + 4.1% per year ([2.9–4.2%], p < 0.001 in men and [3.3–4.9%], p < 0.001 in women, p = 0.6 for men vs women, Fig. 2B). Disease severity as indicated by SAPS II in patients with stroke admitted to the ICU decreased over time in women only (women: OR 0.91 [0.89–0.94], p = 0.002; men OR 0.96 [0.94–0.98], p = 0.08; p = 0.067 for women vs men), while nursing workload (NEMS) decreased in both sexes (overall: OR 0.91, p < 0.001; women: 0.91 [0.89–0.93], p < 0.001; men: 0.92 [0.91–0.93], p < 0.001, Fig. 3B). When mortality trends for stroke over time were adjusted for SAPS II and NEMS, mortality changes were no longer evident.

Discussion

In this large, nationwide registry in Switzerland, sex- and age-specific temporal trends in ICU admission and mortality rates were evaluated in younger patients with AMI or stroke between 2008 and 2019. While we found that the overall mortality rate for AMI in Switzerland has substantially declined by approximately 5% per year over the last 12 years in both men and women, we observed an increasing ICU mortality in younger women with AMI as compared to men. On the other hand, ICU admission rates for AMI decreased significantly more in younger women as compared to men. In stroke patients, a trend toward a decrease in ICU mortality in younger women, but not in men was observed while ICU admission rates increased in both sexes.

The overall decrease in mortality trends observed in women and men with AMI in Switzerland is consistent with published literature and can mainly be attributed to technical refinements, improved therapies, and application of guideline-directed therapies to both sexes leading to a narrowing of the gender gap, which was present in earlier studies [28, 29]. Despite increasing awareness of sex and gender differences in cardiovascular disease manifestation [30, 31], treatment strategies and care [32, 33], younger women still encounter poorer outcomes following an AMI as compared to men [13]. Our data confirm this observation by demonstrating an increase in ICU AMI-related mortality in women ≤ 52 years between 2008 and 2019. Female sex hormones have been discussed to have a protective effect on cardiovascular diseases [34]. Given that the age cutoff in our study population was specifically selected to determine a premenopausal female cohort [24], other factors must outweigh the potential benefit of hormonal cardiovascular protection in critically ill younger women with AMI admitted to ICU. An increase in comorbidities, non-traditional risk factors, and a growing burden of psychosocial stress in younger women, all of them associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes, might account for this time alarming temporal trend [34,35,36]. However, while ICU mortality increased in younger women, we also show that women’s ICU admission rates declined significantly more over time compared to men despite a similar increase in disease severity in both sexes. Therefore, our data indicate that gender inequalities in access to specialized medicine may impose an additional burden on younger women and that triage decisions for ICU admission might have been applied more strictly to the young female population. Gender differences in disease pathophysiology as symptom perception or presentation and diagnostic biases may contribute to the inequality in ICU admission observed between younger women and men [19]. In our study, a drop in ICU admissions for AMI in 2015 can be noted, which was more pronounced in women. At that time, the use of high-sensitive troponin (hs-cTnT) was implemented in triage decisions, allowing to identify patients with smaller myocardial damage at an earlier stage leading to earlier reperfusion therapy and reduced use of ICU resources [37]. Despite international recommendations for sex-specific hs-cTnT cutoff values with younger women having the lowest thresholds [38], the lack to implement them in clinical practice is still evident [39], potentially leading to underestimation or even misdiagnosis of AMI in younger women [40, 41].

The fact that the increased ICU mortality trend in relation to severity of illness in our study was no longer evident indicates that this trend is explainable by the admission of more severely ill patients over the years—which particularly affects the female population given their higher ICU mortality observed. Consistent with published literature, men with AMI in our study were also more frequently referred to reperfusion therapies and received more often organ support upon ICU admission and during ICU stay than women, including mechanical ventilation and vasoactive medication [34, 42]. This phenomenon is known as the ‘Yentl Syndrome’ [43] and might be particularly pronounced in younger women [44].

In contrast to the decline in overall mortality from AMI in Switzerland, stroke-related mortality has not changed over time. However, an increase in ICU admission rates over time in both sexes, alongside a stronger decline in ICU case severity and ICU mortality in younger women, but not in men, was observed in these patients.

The number of stroke patients, in particular younger demographic groups have multiple risk factors and comorbidities such as coagulopathies, smoking, and recreational drug use, has substantially increased during the last decade [45, 46]. The latter might account for the fact that overall stroke-related mortality rates remained stable over time, despite refinements in treatment strategies such as advanced imaging techniques and invasive reperfusion strategies. While ICU admission is frequently limited to the severely affected patient with the need for more invasive monitoring, advanced organ support measures and management of stroke complications, [47,48,49] the increase in ICU admissions over time might also mirror such advances in treatment strategies which necessitates more intense observation following, for example, endovascular treatments. In contrast to AMI patients, the temporal alterations in ICU admissions did not differ between men and women, suggesting that the gender gap, still observed in AMI patients, has narrowed in stroke patients. This finding is supported by previous studies, reporting the disappearance of gender disparities in stroke outcomes when access to specialized therapies, such as thrombolysis or stroke unit admission was provided equally for women and men [51,52,53]. Consistent with this notion, no gender difference was observed in the number of stroke patients being referred for neurovascular interventions, whereas recent studies have even described higher rates of endovascular thrombectomy in women [50, 51]. Less aggressive treatment for stroke prevention in women with atrial fibrillation leading to thromboembolic stroke has been previously discussed as a possible explanation for the higher rates of invasive stroke therapy in women [52]. Given the younger age of our cohort and the lower rates of atrial fibrillation, this may explain the equal rate of interventions observed in our study.

The fact that ICU mortality in our study declined more substantially in female stroke patients than in male patients during the last decade suggests that younger women with stroke have greatly benefited from a closing gender gap in the provision of neurological interventions and intensive care.

There are several limitations to this study that should be pointed out. First, our study is observational and does not provide information on underlying mechanisms. Second, the datasets used contain a limited set of variables. Information on patient demographics, symptoms at presentation, preexisting conditions, cardiovascular risk factors as well as admission criteria or biomarkers (e.g., high-sensitivity troponin) was limited or unavailable in our study sample. Thus, we cannot completely rule out the potential impact of these variables on our study endpoints. Third, the SAPS II score was only available as a whole and not as its separate components. Since it was obtained within the first 24 h after ICU admission, it may not always reflect the severity of illness before ICU admission. In addition, SAPS II as an estimate of case severity and ICU mortality is not a specific marker for neurological impairment as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and does not thoroughly reflect the neurologic deficits upon ICU admission [53]. Fourth, the NEMS score was originally designed to measure the burden of nursing care. Thus, interventions like mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, use of vasoactive agents are only surrogates for patients’ acuity. Fifth, our dataset does not provide information regarding the burden of cardiovascular risk factors and their change over time. However, it seems questionable to what extent these factors play a key role in our investigation since stroke and AMI show different temporal trends. Indeed, as both conditions are associated with the same risk factors, one would expect that their modification results in similar outcomes. Finally, our study was conducted in stroke patients admitted to the ICU and did not include stroke unit admissions, thereby assuming more severe illness in our cohort as compared to intermediate care or stroke unit populations. Consequently, our data may not be extrapolated to patients admitted to stroke units and are limited to the most critically ill.

Conclusion

Our data showing time trends over 12 years in younger individuals with AMI or stroke suggest that gender differences in ICU admission, case severity and mortality still exist in patients with AMI, while the gender gap in the provision of care is closing in stroke patients, resulting in improved outcomes of critically ill women. Although our data are limited by potential confounders not available from the registry, our study emphasizes that triage and selection criteria for ICU admission and invasive treatments, particularly in younger individuals with AMI, should be carefully reassessed. Further research is needed to identify sex- and gender-specific disease modifiers during ICU stay in this population.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the University Hospital Basel Institutional Data Access for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- EKNZ:

-

Ethics Committee of Northwestern Switzerland

- FSO:

-

Swiss Federal Statistical Office

- hs-cTnT:

-

High-sensitive troponin

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MDSi:

-

Minimal Dataset for ICUs

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SSICM:

-

Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine

- NEMS:

-

Nine Equivalents of Nursing Manpower Use Score

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

References

Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(42):3232–45.

Collaborators GBDCoD. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–88.

Koton S, Schneider AL, Rosamond WD, Shahar E, Sang Y, Gottesman RF, et al. Stroke incidence and mortality trends in US communities, 1987 to 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(3):259–68.

Gupta A, Wang Y, Spertus JA, Geda M, Lorenze N, Nkonde-Price C, et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(4):337–45.

Wang Y, Zhou L, Guo J, Wang Y, Yang Y, Peng Q, et al. Secular trends of stroke incidence and mortality in China, 1990 to 2016: the global burden of disease study 2016. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(8): 104959.

Ioacara S, Tiu C, Panea C, Nicolae H, Sava E, Martin S, et al. Stroke mortality rates and trends in Romania, 1994–2017. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(12): 104431.

Madsen TE, Khoury JC, Leppert M, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Sucharew H, et al. Temporal trends in stroke incidence over time by sex and age in the GCNKSS. Stroke. 2020;51(4):1070–6.

Krishnamurthi RV, Moran AE, Feigin VL, Barker-Collo S, Norrving B, Mensah GA, et al. Stroke prevalence, mortality and disability-adjusted life years in adults aged 20–64 years in 1990–2013: data from the global burden of disease 2013 study. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):190–202.

Ekker MS, Boot EM, Singhal AB, Tan KS, Debette S, Tuladhar AM, et al. Epidemiology, aetiology, and management of ischaemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):790–801.

Yahya T, Jilani MH, Khan SU, Mszar R, Hassan SZ, Blaha MJ, et al. Stroke in young adults: current trends, opportunities for prevention and pathways forward. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;3: 100085.

Ekker MS, Verhoeven JI, Vaartjes I, van Nieuwenhuizen KM, Klijn CJM, de Leeuw FE. Stroke incidence in young adults according to age, subtype, sex, and time trends. Neurology. 2019;92(21):e2444–54.

Giroud M, Delpont B, Daubail B, Blanc C, Durier J, Giroud M, et al. Temporal trends in sex differences with regard to stroke incidence: the dijon stroke registry (1987–2012). Stroke. 2017;48(4):846–9.

Gabet A, Danchin N, Juilliere Y, Olie V. Acute coronary syndrome in women: rising hospitalizations in middle-aged French women, 2004–14. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(14):1060–5.

Arora S, Stouffer GA, Kucharska-Newton AM, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Pandey A, et al. Twenty Year trends and sex differences in young adults hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2019;139(8):1047–56.

DeFilippis EM, Collins BL, Singh A, Biery DW, Fatima A, Qamar A, et al. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(42):4127–37.

Izadnegahdar M, Singer J, Lee MK, Gao M, Thompson CR, Kopec J, et al. Do younger women fare worse? Sex differences in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and early mortality rates over ten years. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):10–7.

Leifheit-Limson EC, D’Onofrio G, Daneshvar M, Geda M, Bueno H, Spertus JA, et al. Sex differences in cardiac risk factors, perceived risk, and health care provider discussion of risk and risk modification among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: the VIRGO study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(18):1949–57.

Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Myer PA, Singh G. Obesity, abdominal obesity, physical activity, and caloric intake in US adults: 1988 to 2010. Am J Med. 2014;127(8):717–27.

Todorov A, Kaufmann F, Arslani K, Haider A, Bengs S, Goliasch G, et al. Gender differences in the provision of intensive care: a Bayesian approach. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:577.

Perren A, Cerutti B, Kaufmann M, Rothen HU, Swiss Society of Intensive Care M. A novel method to assess data quality in large medical registries and databases. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(7):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy249.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Le Gall J-R, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270(24):2957–63.

Reis Miranda D, Moreno R, Iapichino G. Nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS). Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(7):760–5.

Dratva J, Zemp E, Staedele P, Schindler C, Constanza MC, Gerbase M, et al. Variability of reproductive history across the Swiss SAPALDIA cohort–patterns and main determinants. Ann Hum Biol. 2007;34(4):437–53.

Ekker MS, Verhoeven JI, Vaartjes I, Jolink WMT, Klijn CJM, de Leeuw FE. Association of stroke among adults aged 18 to 49 years with long-term mortality. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2113–23.

Hughes G. Youden’s index and the weight of evidence. Methods Inf Med. 2015;54(2):198–9.

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2019 [Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Radovanovic D, Seifert B, Roffi M, Urban P, Rickli H, Pedrazzini G, et al. Gender differences in the decrease of in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction during the last 20 years in Switzerland. Open Heart. 2017;4(2): e000689.

Sabbag A, Matetzky S, Gottlieb S, Fefer P, Kohanov O, Atar S, et al. Recent temporal trends in the presentation, management, and outcome of women hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Med. 2015;128(4):380–8.

Winham SJ, de Andrade M, Miller VM. Genetics of cardiovascular disease: importance of sex and ethnicity. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241(1):219–28.

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):565–82.

Vervloet M, Korevaar JC, Leemrijse CJ, Paget J, Zullig LL, van Dijk L. Interventions to improve adherence to cardiovascular medication: what about gender differences? A systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2055–70.

Punnoose LR, Lindenfeld J. Sex-specific differences in access and response to medical and device therapies in heart failure: state of the art. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(5):640–8.

Vallabhajosyula S, Verghese D, Desai VK, Sundaragiri PR, Miller VM. Sex differences in acute cardiovascular care: a review and needs assessment. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(3):667–85.

Haider A, Bengs S, Luu J, Osto E, Siller-Matula JM, Muka T, et al. Sex and gender in cardiovascular medicine: presentation and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(13):1328–36.

Dreyer RP, Smolderen KG, Strait KM, Beltrame JF, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, et al. Gender differences in pre-event health status of young patients with acute myocardial infarction: a VIRGO study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(1):43–54.

Reichlin T, Twerenbold R, Reiter M, Steuer S, Bassetti S, Balmelli C, et al. Introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays: impact on myocardial infarction incidence and prognosis. Am J Med. 2012;125(12):1205–13.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138(20):e618–51.

Rubini Gimenez M, Twerenbold R, Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Puelacher C, Hillinger P, et al. Clinical effect of sex-specific cutoff values of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T in suspected myocardial infarction. JAMA cardiology. 2016;1(8):912–20.

Gartner C, Langhammer R, Schmidt M, Federbusch M, Wirkner K, Loffler M, et al. Revisited upper reference limits for highly sensitive cardiac troponin T in relation to age, sex, and renal function. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5508.

Lee KK, Ferry AV, Anand A, Strachan FE, Chapman AR, Kimenai DM, et al. Sex-specific thresholds of high-sensitivity troponin in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(16):2032–43.

Modra LJ, Higgins AM, Abeygunawardana VS, Vithanage RN, Bailey MJ, Bellomo R. Sex differences in treatment of adult intensive care patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(6):913–23.

Healy B. The Yentl syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):274–6.

D’Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Geda M, et al. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO study. Circulation. 2015;131(15):1324–32.

George MG, Tong X, Bowman BA. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and strokes in younger adults. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(6):695–703.

Khan SU, Khan MZ, Khan MU, Khan MS, Mamas MA, Rashid M, et al. Clinical and economic burden of stroke among young, midlife, and older adults in the United States, 2002–2017. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(2):431–41.

Kirkman MA, Citerio G, Smith M. The intensive care management of acute ischemic stroke: an overview. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(5):640–53.

Carval T, Garret C, Guillon B, Lascarrou JB, Martin M, Lemarie J, et al. Outcomes of patients admitted to the ICU for acute stroke: a retrospective cohort. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22(1):235.

van Valburg MK, Arbous MS, Georgieva M, Brealey DA, Singer M, Geerts BF. Clinical predictors of survival and functional outcome of stroke patients admitted to critical care. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(7):1085–92.

Weber R, Krogias C, Eyding J, Bartig D, Meves SH, Katsanos AH, et al. Age and sex differences in ischemic stroke treatment in a nationwide analysis of 1.11 million hospitalized cases. Stroke. 2019;50(12):3494–502.

Otite FO, Saini V, Sur NB, Patel S, Sharma R, Akano EO, et al. Ten-year trend in age, sex, and racial disparity in tPA (Alteplase) and thrombectomy use following stroke in the United States. Stroke. 2021;52(8):2562–70.

Rexrode KM, Madsen TE, Yu AYX, Carcel C, Lichtman JH, Miller EC. The impact of sex and gender on stroke. Circ Res. 2022;130(4):512–28.

Lyden PD, Lu M, Levine SR, Brott TG, Broderick J, Group NrSS. A modified National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale for use in stroke clinical trials: preliminary reliability and validity. Stroke. 2001;32(6):1310–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christian Schindler (senior statistician of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland) for providing expert advice on the statistical analysis and for critically reviewing the manuscript. We thank Gian-Paolo Klinke and Erwin Wüest (Federal Statistical Office, Department of Health) for providing us with the nationwide data of patients with stroke or AMI in Switzerland.

Funding

CEG was supported by grants from the Research Foundation in Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital Basel, the Research Fund of the University of Basel, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). CG was supported by grants from the SNSF, the Olga Mayenfisch Foundation, Switzerland, the OPO Foundation, Switzerland, the Novartis Foundation, Switzerland, the Swissheart Foundation, the Helmut Horten Foundation, Switzerland, the EMDO Foundation, Switzerland, the Iten-Kohaut Foundation/University Hospital Zurich Foundation, Switzerland, and the University of Zurich Foundation. KA has received a research grant from the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner-Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation (P500PM_202963), Switzerland, outside the submitted work. KW has received research funding from the Gottfried und Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, the Prince Charles Hospital Foundation, the Wesley Medical Research Foundation, the CRE ACTION (Centre of Research Excellence for Advanced Cardio-Respiratory Therapies improving Organ Support) a PhD scholarship from the University of Queensland (Brisbane, Australia), all outside the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

KA, JT, CEG and AT contributed to design and conduct of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, and had final responsibility in the decision to submit for publication. KA, JT, CEG and AT had full access to the data. All authors provided critical feedback at various stages of the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In the annual assembly in autumn 2015, the members of the SSICM agreed that all pseudonymized data from the MDSi can be used for research, once a specific request has been approved by the appropriate scientific committee. The Ethics committee of Northwestern Switzerland approved this procedure (EKNZ UBE-15/47). The scientific committee of the SSICM approved the study with the above-mentioned title.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CG has received speakers’ fees from Sanofi Genzyme, travel support from Siemens Health engineers, and research support from the Novartis Foundation, Switzerland, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and Gerresheimer AG, Switzerland. The Department of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital Zurich, holds a research contract with GE Healthcare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Table S1. STROBE Statement—Checklist of items

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arslani, K., Tontsch, J., Todorov, A. et al. Temporal trends in mortality and provision of intensive care in younger women and men with acute myocardial infarction or stroke. Crit Care 27, 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04299-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04299-0