Abstract

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a complex environment where patients, family members and healthcare professionals have their own personal experiences. Improving ICU experiences necessitates the involvement of all stakeholders. This holistic approach will invariably improve the care of ICU survivors, increase family satisfaction and staff wellbeing, and contribute to dignified end-of-life care. Inclusive and transparent participation of the industry can be a significant addition to develop tools and strategies for delivering this holistic care. We present a report, which follows a round table on ICU experience at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. The aim is to discuss the current evidence on patient, family and healthcare professional experience in ICU is provided, together with the panel’s suggestions on potential improvements. Combined with industry, the perspectives of all stakeholders suggest that ongoing improvement of ICU experience is warranted.

Introduction

Critical illness impacts patient and relatives. Evidence suggests that prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stay is associated with physical, mental, cognitive and psychological sequelae for ICU survivors, which can persist long after ICU discharge (Post-ICU Syndrome). Decision-making during ICU stay is often shared with patient’s relatives, which can increase the inherent anxiety and depression from having a loved-one in the ICU [1]. Furthermore, the ICU environment is an emotional place for healthcare professionals, who experience challenging situations that provoke conflicting emotions such as isolation, sadness, anger, shame, love, and happiness [2].

Structured interventions and approaches aimed at improving patient, family and healthcare experiences have recently been the focus of research in the ICU [3,4,5]. We present an overview of the discussion raised by a panel of experts, who participated in a GE Healthcare-sponsored symposium held during the LIVES2021 congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). This was a multi-national and multi-disciplinary symposium with presentations from colleagues with extensive experience in ICU. We decided to add representation from the sponsoring company, recognising the importance of technology in creating an optimum ICU environment. The aim of this report is to discuss and present expert suggestions that may improve the ICU experience of patients, their relatives, and healthcare professionals, including the perspectives of industry.

The patient perspective

Individual aspects of patient experience, such as quality of sleep, pain and sedation, are measured during ICU admission to guide and assess our interventions. The ICU survivors recall their experience to varying degrees and their recollection may be factual or illusory [6]. Measuring and understanding recalled patient discomfort has the potential to provide a global measure of patient ICU experience.

Measuring recalled discomfort

Van de Leur et al. demonstrated a link between patient’s factual recall of ICU events and the recollection of discomfort experienced during an ICU stay [7]. Focusing on recalled discomfort is important because it is associated with post-ICU syndromes, such as sleep disturbance, anxiety, mood disorders and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The validated IPREA (Inconforts des Patients de REAnimation) questionnaire measures perceived or recalled discomfort from an ICU episode and can be used irrespective of the diagnosis, the disease or the organ support the patient receives. The ICU survivors are asked at ICU discharge about possible causes of discomfort, using an 18-item questionnaire, and rate the severity of each cause. The questionnaire has been translated into English [8]. The IPREA studies show that sleep deprivation, discomfort due to lines and tubes, pain, and thirst are the highest scored items on the discomfort scale [9], with ICU experiences of discomfort being similar across countries and cultures.

Improving patient experience

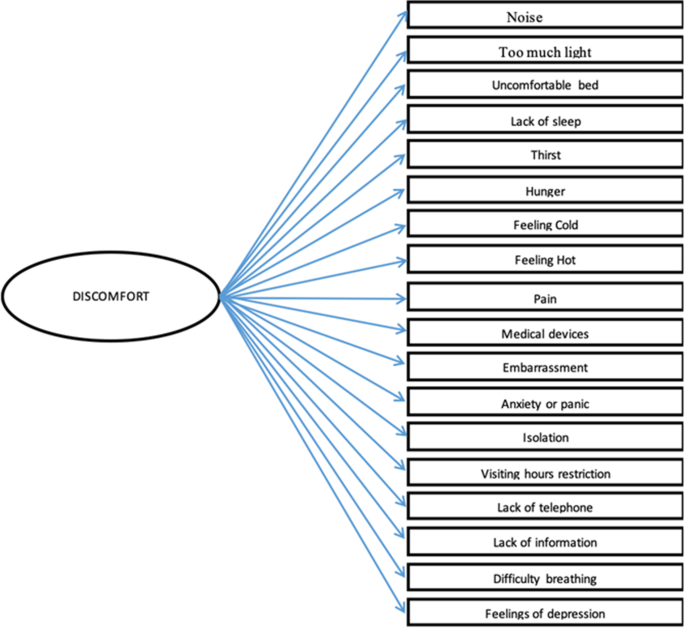

Consideration of the 18 domains of discomfort in Fig. 1 (adapted from Kalfon et al. [10]) should be incorporated in ICU daily practice. By understanding patient experiences and components of their discomfort clinicians can modify the ICU environment, the care provided and the communication with patients. Environmental factors in ICU design that should be considered include noise reduction, provision of natural light, presence of a clock, telephone and TV, as well as maintaining privacy. Aspects of ICU care such as visiting hours, communication of information, mouth and airway care, pain and sedation are paramount in delivering high quality and safe care to ICU patients.

The incidence of PTSD in ICU survivors is approximately 20%. There have been mixed successes in studies using interventions to mitigate PTSD development in the post-ICU phase. The POPPI study, a nurse-led preventative psychological intervention among ICU survivors, did not demonstrate significant reduction in PTSD symptoms at 6 months [11]. In contrast, the IPREA AQVAR group published a tailored multi-component programme, which used comfort champions and local strategies and showed a significant reduction in overall discomfort and a decrease in PTSD at 12 months post-ICU discharge [12]. Another recent study reported reduction in PTSD symptoms using a virtual reality programme for ICU discharged patients [13].

Exploring discomfort post-ICU discharge can provide insights into patient ICU experiences and the impact of quality of care. The incidence or severity of post-ICU syndromes may be reduced by addressing various aspects of discomfort, but more research is warranted. Suggestions to reduce discomfort among ICU patients are presented in Table 1. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted even more the importance of assessing ICU patient experiences and the long-term impact of critical illness and ICU interventions.

The family perspective

Family-centred care is defined as an approach to healthcare that is respectful of and responsive to individual families’ needs and values, and in which partnership and collaboration are key concepts [4, 14]. Research has contributed to develop family-centred care by helping clinicians to better understand and improve family members’ experience.

Humanizing the ICU

Debates over closed versus open visiting policies have been numerous, with significant variations in practice between and within countries [15, 16]. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic generated a considerable setback, as ICUs felt compelled to restrict visiting. Importantly, open visiting policies are associated with decreased anxiety and better understanding of information [17]. In the technical ICU environment, qualitative research has provided dimensions of humanization important to family members, such as personalization (vs. objectification), agency (vs. passivity), togetherness (vs. isolation) and sense-making (vs. loss of meaning) [18]. Moreover, families in the ICU are sensitive to clinicians’ empathy and to reciprocal relationships [19].

Families’ psychological burden

Family members are extremely vulnerable during the patient’s ICU stay. They only understand approximately half of the medical information given to them by the ICU team [20], generating difficulties to adapt and manage hope. Families also remain vulnerable after the patient’s discharge or death. Three months post-ICU discharge, up to 70% suffer from symptoms of anxiety, 35% from symptoms of depression [21], and up to one third suffer from PTSD-related symptoms [22].

Communication

Communication is at the heart of the family’s experience. It consists of verbal communication (words) and non-verbal communication (body language), the latter determining the quality of the speakers’ message and its ability to be received [23]. In highly emotional situations, such as being in ICU, family members are extremely sensitive to non-verbal communication. The quality of overall communication impacts on relatives’ well-being: unsatisfactory communication is associated with higher risk of developing PTSD related symptoms [22] and in bereaved relatives, it is associated with increased risk of developing complicated grief at 6 and 12 months after the patient’s death [2].

Improving family experience

Most randomized controlled trials aiming to improve families’ wellbeing have focused on improving communication between ICU clinicians and relatives. The Family End-of-Life Conference, a meeting between the patient’s clinicians and the family, encourages clinicians to Value family statements, Acknowledge family emotions, Listen to the family, Understand the patient as person and Elicit questions from families [3]. In a French trial, this pro-active communication strategy was associated with a decreased risk of developing anxiety, depression and PTSD related symptoms three months after the patient’s death [24]. Including a nurse facilitator in the family conferences was associated with a decreased risk of developing depression symptoms in family members 6 months after the patient’s ICU discharge or death [25]. Furthermore, a three-step support strategy for relatives of patients dying after a decision to withdraw treatment, including a family conference before the patient’s death, a room visit during dying and death, and a meeting after the patient’s death, was associated with a decreased risk of developing prolonged grief, as well as anxiety, depression and PTSD related symptoms 6 months after the patient’s death [26]. More research is needed to evaluate the developed strategies as some interventions have proven to be deleterious [27, 28]. Suggestions to improve the family experiences are presented in Table 2.

The healthcare professionals’ perspective

The COVID-19 pandemic generated a new dimension on the experiences of ICU professionals. Survey studies have indicated the increase physical and psychological burden of ICU staff while caring for COVID patients [29,30,31]. Qualitative studies generated a deeper understanding of the impact [32, 33], which can be summarised as the ‘emotional impact affecting the personal self’, the ‘professional fellowship among colleagues’ and the ‘recognition and support from the outside’.

Emotional comfort

The experiences of ICU healthcare professionals have mainly been studied by qualitative research methods [5, 34]. In these studies, a range of emotions have been identified, with one of the six reported themes being that of emotional impact [35]. Within this theme, ICU nurses addressed empathy as an important skill to develop, whereas for ICU doctors, the overarching themes were the risk and benefits of empathy, the spectrum of connection and distance from patients/families, and the facilitators and barriers to empathy development [36]. A scoping review indicated that empathy among intensivists is not a dichotomous phenomenon and that a deeper understanding is needed to create a supportive environment where ICU professionals feel safe to demonstrate their empathy to patients and relatives [36].

Complexity of decision-making

The complexity of ICU patients and their pathway to recovery or death influences the performance of ICU staff and impact on their mental health. This complexity does not only relate to caring for certain patient groups but also to participation in decision-making. The involvement in decisions relating to treatment withdrawal or organ donation has been challenging for many ICU professionals [37,38,39]. The low research priority given to delirium care has caused frustration to ICU nurses, due to the resulting lack of confidence in assessing delirium.15 Most studies conclude that continuous specialist education is required to provide high quality-of-care to the increasingly complex ICU patient.

Improving healthcare professional experience

Improving the ICU experience of healthcare professionals is necessary in order to maintain safe ICU environment, high quality ICU staffing and a sustainable workforce. It is essential for the formation of a positive ICU climate, which will help healthcare professionals cope with the most complex needs of ICU patients and relatives, and provide high quality of care [40, 41]. Staff empathy skills can be taught, as demonstrated by a 5-day course on empathy education, including simulation training, which significantly increased the empathy levels of student nurses [42]. Further suggestions to support the health and well-being of ICU health professionals are presented in Table 3.

The industry perspective

Professional organizations are describing the ICU as ‘very daunting place… equipped with many devices to monitor the patients… sophisticated machines and screens... alarms… with the devices connected to a central station…’ [43].

Medical devices and impact on comfort

Medical devices, such as ventilators, renal replacement equipment, infusion pumps and extracorporeal membrane oxygenators have the potential to influence patients’, families’ and healthcare professionals’ ICU experience. In Fig. 1 it is obvious that discomfort is often generated by medical equipment, such as alarms inducing excess of noise or lines, tubes and cables constraining the patient. Noise is a common source of patient discomfort and may have negative impact on the visiting family and healthcare professionals [10]. By mapping the various sources of noise in ICU, Darbyshire et al. found that a significant proportion originated from equipment alarms in extremely limited areas, very close to patients’ ears [44].

Improving by digital transformation

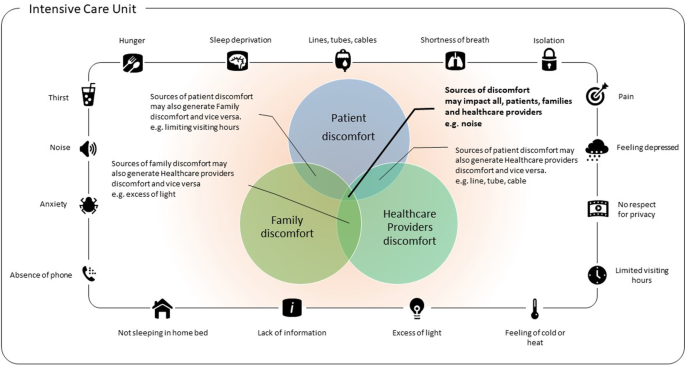

The contribution of industry can have a positive impact on the entire ICU ecosystem (Fig. 2). By digital adjustment and automatization, the unavoidable clerical burden needed for resource allocation and documentation, can be alleviated, allowing staff to dedicate their time to spending clinical time with patients and the families. In an 18-bed academic medical-surgical ICU, Bosman et al. reported a 30% reduction in documentation time by using a clinical information system at the bedside; time, which was completely re-allocated to patient care [45]. The digital transformation of ICU helps reduce not only the documentation burden but also improves patient comfort and family engagement and communication. Dashboards displaying discomfort scores may act as reminders and influence the provided care, enhancing ICU experience. A dedicated ICU clinical information system may also general reminders to alert ICU staff that a communication with the family is needed and thus preventing potential conflict.

If patient’s discomfort is relatively well documented (Baumstarck 2014), family discomfort and healthcare provider discomfort need to be further investigated. The concept is assuming that some of the source of discomfort are unavoidably shared by all the participants (patient, family, healthcare providers). Improving ICU experience by reducing discomfort may be best achieved by considering the entire ICU ecosystem, including peoples (patient, family, healthcare providers), various workflow and process and the surrounding medical equipment and devices.

A redesign of the ICU environment to move alarm sounds away from the bedside may significantly reduce noise-related discomfort. Improving the operational value and the usability of alarm signals, without being unnecessarily distracting or disturbing, is also the goal of recently updated safety standards (ISO 60601-1-8) which need to be followed by manufacturing companies. Sophisticated stand alone or embedded alarm management solutions have been developed not only to reduced noise-related discomfort but also to avoid family anxiety and caregivers’ annoyance and alarm fatigue [46]. Collaboration in equipment design and digital solutions between clinicians, patients and industry is part of the solution for stakeholder experience in ICU.

Discussion

Critically ill patients experience various discomforts during their ICU stay, that may be related to the environment (noise, light, temperature, etc.), some aspects of care organisation (continuous light, limited visiting hours, lack of privacy, etc.), and also specific ICU therapeutics (mechanical invasive and non-invasive ventilation renal replacement therapy, or painful procedures). This conference paper has focused on interventions that may enhance ICU experience not only for patients but also for families and critical care staff. The daily assessment and recognition of potential patient discomfort in ICU will ensure greater insight into their experience and improve the quality of the offered care. Improving communication both at an individual but also at a collective level has been highlighted as the most important intervention for improving family experience, by making family-centred care a quality standard. Revisiting ICU staffing models and training of nurses and doctors on empathy and communication skills are important in order to create a positive ICU climate with a sustainable workforce. The transparent involvement and collaboration of industry in developing tools and technologies that are aimed at humanising the ICU environment is increasingly recognised as an important part of the equation.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–24.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, Lefrant JY, Floccard B, Renault A, Vinatier I, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1341–52.

Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Tonelli MR, Patrick DL, Robins LS, McGrath BB, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):147–60.

Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, Spuhler V, Todres ID, Levy M, Barr J, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–22.

Jakimowicz S, Perry L, Lewis J. Insights on compassion and patient-centred nursing in intensive care: a constructivist grounded theory. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):1599–611.

Cook DJ, Meade MO, Perry AG. Qualitative studies on the patient’s experience of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001;120(6 Suppl):469s–73s.

van de Leur JP, van der Schans CP, Loef BG, Deelman BG, Geertzen JH, Zwaveling JH. Discomfort and factual recollection in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2004;8(6):R467-473.

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104.

Jacques T, Ramnani A, Deshpande K, Kalfon P. Perceived discomfort in patients admitted to intensive care (DETECT DISCOMFORT 1): a prospective observational study. Crit Care Resusc. 2019;21(2):103–9.

Kalfon P, Mimoz O, Auquier P, Loundou A, Gauzit R, Lepape A, Laurens J, Garrigues B, Pottecher T, Mallédant Y. Development and validation of a questionnaire for quantitative assessment of perceived discomforts in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(10):1751–8.

Wade DM, Mouncey PR, Richards-Belle A, Wulff J, Harrison DA, Sadique MZ, Grieve RD, Emerson LM, Mason AJ, Aaronovitch D, et al. Effect of a nurse-led preventive psychological intervention on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among critically Ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(7):665–75.

Kalfon P, Alessandrini M, Boucekine M, Renoult S, Geantot MA, Deparis-Dusautois S, Berric A, Collange O, Floccard B, Mimoz O, et al. Tailored multicomponent program for discomfort reduction in critically ill patients may decrease post-traumatic stress disorder in general ICU survivors at 1 year. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(2):223–35.

Vlake JH, Van Bommel J, Wils EJ, Korevaar TIM, Bienvenu OJ, Klijn E, Gommers D, van Genderen ME. Virtual reality to improve sequelae of the postintensive care syndrome: a multicenter, randomized controlled feasibility study. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(9):e0538.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–28.

Milner KA, Goncalves S, Marmo S, Cosme S. Is open visitation really “open” in adult intensive care units in the United States? Am J Crit Care. 2020;29(3):221–5.

Simon SK, Phillips K, Badalamenti S, Ohlert J, Krumberger J. Current practices regarding visitation policies in critical care units. Am J Crit Care. 1997;6(3):210–7.

Ning J, Cope V. Open visiting in adult intensive care units—a structured literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;56:102763.

Todres L, Galvin KT, Holloway I. The humanization of healthcare: a value framework for qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2009;4(2):68–77.

Nelson JE, Puntillo KA, Pronovost PJ, Walker AS, McAdam JL, Ilaoa D, Penrod J. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):808–18.

Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, Canoui P, Le Gall JR, Schlemmer B. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3044–9.

Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, Hopkins RO, Rice TW, Bienvenu OJ, Azoulay E. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):725–38.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–94.

Burgoon JK, Guerrero LK, Kory F. Nonverbal communication. New York: Routledge; 2016.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, Barnoud D, Bleichner G, Bruel C, Choukroun G, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–78.

Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Gold J, Ciechanowski PS, Shannon SE, Khandelwal N, Young JP, Engelberg RA. Randomized trial of communication facilitators to reduce family distress and intensity of end-of-life care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(2):154–62.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Valade S, Jaber S, Kerhuel L, Guisset O, Martin M, Mazaud A, Papazian L, Argaud L, et al. A three-step support strategy for relatives of patients dying in the intensive care unit: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):656–64.

Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, Chai E, Nelson JE. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(1):51–62.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Champigneulle B, Thirion M, Souppart V, Gilbert M, Lesieur O, Renault A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Argaud L, et al. Effect of a condolence letter on grief symptoms among relatives of patients who died in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(4):473–84.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Reignier J, Argaud L, Bruneel F, Courbon P, Cariou A, Klouche K, Labbé V, Barbier F, et al. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care physicians facing the second COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021;160(3):944–55.

Mehta S, Yarnell C, Shah S, Dodek P, Parsons-Leigh J, Maunder R, Kayitesi J, Eta-Ndu C, Priestap F, LeBlanc D, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intensive care unit workers: a nationwide survey. Can J Anaesth. 2021;69:1–13.

Zhang Y, Wang C, Pan W, Zheng J, Gao J, Huang X, Cai S, Zhai Y, Latour JM, Zhu C. Stress, burnout, and coping strategies of frontline nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan and Shanghai, China. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:565520.

Fernández-Castillo RJ, González-Caro MD, Fernández-García E, Porcel-Gálvez AM, Garnacho-Montero J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(5):397–406.

Kackin O, Ciydem E, Aci OS, Kutlu FY. Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: a qualitative study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(2):158–67.

Limbu S, Kongsuwan W, Yodchai K. Lived experiences of intensive care nurses in caring for critically ill patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2019;24(1):9–14.

Magro-Morillo A, Boulayoune-Zaagougui S, Cantón-Habas V, Molina-Luque R, Hernández-Ascanio J, Ventura-Puertos PE. Emotional universe of intensive care unit nurses from Spain and the United Kingdom: a hermeneutic approach. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;59:102850.

Bunin J, Shohfi E, Meyer H, Ely EW, Varpio L. The burden they bear: a scoping review of physician empathy in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2021;65:156–63.

Boissier F, Seegers V, Seguin A, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, Lefrant JY, Rimmelé T, Renault A, Vinatier I, et al. Assessing physicians’ and nurses’ experience of dying and death in the ICU: development of the CAESAR-P and the CAESAR-N instruments. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):521.

Simonsson J, Keijzer K, Södereld T, Forsberg A. Intensive critical care nurses’ with limited experience: experiences of caring for an organ donor during the donation process. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(9–10):1614–22.

Taylor IHF, Dihle A, Hofsø K, Steindal SA. Intensive care nurses’ experiences of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care patients: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;56:102768.

Van den Bulcke B, Metaxa V, Reyners AK, Rusinova K, Jensen HI, Malmgren J, Darmon M, Talmor D, Meert AP, Cancelliere L, et al. Ethical climate and intention to leave among critical care clinicians: an observational study in 68 intensive care units across Europe and the United States. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(1):46–56.

Van den Bulcke B, Piers R, Jensen HI, Malmgren J, Metaxa V, Reyners AK, Darmon M, Rusinova K, Talmor D, Meert AP, et al. Ethical decision-making climate in the ICU: theoretical framework and validation of a self-assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(10):781–9.

Ding X, Wang L, Sun J, Li DY, Zheng BY, He SW, Zhu LH, Latour JM. Effectiveness of empathy clinical education for children’s nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;85:104260.

European Society of Intensive Care: What is Intensive Care. https://www.esicm.org/patient-and-family/what-is-intensive-care. Accessed 10th April 2022.

Darbyshire JL, Müller-Trapet M, Cheer J, Fazi FM, Young JD. Mapping sources of noise in an intensive care unit. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(8):1018–25.

Bosman RJ, Rood E, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Van der Spoel JI, Wester JP, Zandstra DF. Intensive care information system reduces documentation time of the nurses after cardiothoracic surgery. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(1):83–90.

Kane-Gill SL, O’Connor MF, Rothschild JM, Selby NM, McLean B, Bonafide CP, Cvach MM, Hu X, Konkani A, Pelter MM, et al. Technologic distractions (part 1): summary of approaches to manage alert quantity with intent to reduce alert fatigue and suggestions for alert fatigue metrics. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):1481–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

GE-Healthcare organised the industry-sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. The speakers and chairs of this session received funding from GE Healthcare. GE Healthcare was involved in the programme but not involved in the content of the presentations. GE Healthcare was involved in the previous draft of this manuscript and delivered the content of the section ‘the industry perspective’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VM and EA were the chairs of the industry-sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress and wrote the introduction and discussion sections of the manuscript. TJ, NKB and JML were speakers at the industry-sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress and wrote the first three main perspectives sections of the manuscript. MW organised the industry-sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress and wrote the section on industry perspectives. All authors wrote parts of the manuscript text. TJ prepared Fig. 1 and Table 1; NKB prepared Table 2; JML prepared Table 3; MW prepared Fig. 2. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

JML has over 30 years of critical care experience as a nurse and is currently a professor in clinical nursing. His main clinical and academic interest and achievements in ICU are family-centred care, ICU staff leadership and shared decision-making. He is the Chair-elect of the Ethics Section of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

NKB is a sociologist and currently co-director of the Famiréa research group at the Saint Louis hospital, AP-HP, France. Her research includes quantitative and qualitative studies on end-of-life in the ICU, communication and support strategies, post-ICU burden, and organ donation.

TJ was Director of ICU, St George Hospital, Australia for over 30 years. She has a longstanding interest in the long term outcome of ICU care and education and simulation. Her study on measuring patient comfort was awarded best scientific paper by the College of Intensive Care Medicine in 2018.

MW is a board certified intensivist and was practicing for almost 20 years as senior ICU co-director of a university affiliated hospital in Paris, France. As global medical director for GE Healthcare his clinical and academic expertise on various ICU domains is instrumental to the development of medical device and solutions in the acute care domain.

EA is an Intensive care medicine specialist at the Saint-Louis university hospital of Paris and Paris Cité University.

VM is a consultant in Critical Care in King’s College Hospital, London. Her main academic and clinical interests are palliative care and end of life in ICU, management of patients with haemato-oncological malignancy and critical care outreach services.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The financial competing interest are: JML, NKB; TJ, EA and VM received a fee for presenting or chairing at the GE Healthcare sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress. MW is a representative of GE Healthcare, and this commercial company sponsored the industry-sponsored session at the LIVES2021 congress. GE Healthcare adhered to the Good Publication Practice guidelines for pharmaceutical companies. In addition, EA has received fees for lectures from Gilead, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Alexion. His research group has been supported by Baxter, Fisher & Payckle, Jazz Pharma, and MSD. VM has received lecturing fees from Gilead. The non-financial competing interests are: All authors declare that the content of the manuscript reflect their own view and not of any organisation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Latour, J.M., Kentish-Barnes, N., Jacques, T. et al. Improving the intensive care experience from the perspectives of different stakeholders. Crit Care 26, 218 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04094-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04094-x