Abstract

Background

Excessive inspiratory effort could translate into self-inflicted lung injury, thus worsening clinical outcomes of spontaneously breathing patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF). Although esophageal manometry is a reliable method to estimate the magnitude of inspiratory effort, procedural issues significantly limit its use in daily clinical practice. The aim of this study is to describe the correlation between esophageal pressure swings (ΔPes) and nasal (ΔPnos) as a potential measure of inspiratory effort in spontaneously breathing patients with de novo ARF.

Methods

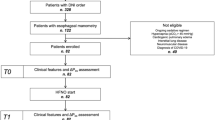

From January 1, 2021, to September 1, 2021, 61 consecutive patients with ARF (83.6% related to COVID-19) admitted to the Respiratory Intensive Care Unit (RICU) of the University Hospital of Modena (Italy) and candidate to escalation of non-invasive respiratory support (NRS) were enrolled. Clinical features and tidal changes in esophageal and nasal pressure were recorded on admission and 24 h after starting NRS. Correlation between ΔPes and ΔPnos served as primary outcome. The effect of ΔPnos measurements on respiratory rate and ΔPes was also assessed.

Results

ΔPes and ΔPnos were strongly correlated at admission (R2 = 0.88, p < 0.001) and 24 h apart (R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001). The nasal plug insertion and the mouth closure required for ΔPnos measurement did not result in significant change of respiratory rate and ΔPes. The correlation between measures at 24 h remained significant even after splitting the study population according to the type of NRS (high-flow nasal cannulas [R2 = 0.79, p < 0.001] or non-invasive ventilation [R2 = 0.95, p < 0.001]).

Conclusions

In a cohort of patients with ARF, nasal pressure swings did not alter respiratory mechanics in the short term and were highly correlated with esophageal pressure swings during spontaneous tidal breathing. ΔPnos might warrant further investigation as a measure of inspiratory effort in patients with ARF.

Trial registration: NCT03826797. Registered October 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inspiratory effort producing excessive transpulmonary pressure (PL) plays a key role in the progression of lung damage during acute respiratory failure (ARF) of different etiology [1], including severe COVID-19 pneumonia [2]. Negative alveolar pressure, pendelluft phenomenon, local overstretch of dependent lung zones and asymmetrical distribution of PL applied to inhomogeneous lung parenchyma are the putative mechanisms of self-inflicted injury (P-SILI) and worse outcomes observed in patients with ARF and breathing spontaneously [3, 4].

Esophageal pressure swings (ΔPes) mirror the mean PL during non-assisted spontaneous breathing, thus esophageal manometry provides an estimate of the magnitude of inspiratory effort [5] and it is a predictor of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV) failure [4, 6]. However, esophageal manometry is not easy to implement at the bedside [7], especially in unstable patients with respiratory distress and severe impairment of gas exchange [8, 9]. Notwithstanding, an easy-to-perform respiratory monitoring of patients with ARF would be useful in all patients at risk of P-SILI [8]. In particular, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has increased the number of patients with ARF breathing spontaneously and requiring non-invasive respiratory support (NRS), especially outside the intensive care units (ICUs) [10]. These patients are at high risk of deterioration and could therefore benefit from continuous monitoring of inspiratory effort [11].

Early physiological studies comparing ΔPes with nasal (ΔPnos) and mouth pressure swings, showed no phase difference between pressure waveforms during incremental inspiratory effort [12]. A significant correlation between ΔPes and airway pressure swings (ΔPaw) during an inspiratory effort test, as obtained by an occlusion maneuver, was also observed [13, 14].

The aim of this proof-of-concept physiological study was to describe the correlation between ΔPes and ΔPaw as captured by ΔPnos in a cohort of spontaneously breathing patients with de novo ARF candidate to receive a non-invasive respiratory support (HFNC and NIV). We hypothesized that ΔPes and ΔPnos were correlated, also during application of different types of NRS.

Methods

Study cohort

Patients with ARF admitted to the Respiratory Intensive Care Unit (RICU) at the University Hospital of Modena between January 1st, 2021, and September 1st, 2021, were prospectively considered eligible for enrollment. This was a pre-planned sub-study of a prospectively registered protocol (ClinicalTrial.gov: ID NCT03826797). The local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Area Vasta Emilia Nord) approved the study approval (protocol number 4485/C.E., document 266/16) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their relatives, as appropriate.

Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years; presence of ARF with a peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) < 90% during conventional oxygen therapy with Venturi mask with an inspiratory oxygen fraction (FiO2) of 0.5 and candidate to treatment escalation to high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and consent to receive esophageal and nasal manometry assessment. Exclusion criteria were immediate need for endotracheal intubation; cardiogenic acute pulmonary edema or concomitant hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mmHg); previous diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, neuromuscular diseases, anatomical alterations of the nasal tract, or chest wall deformities; use of home long-term oxygen therapy.

Clinical variables and measurements

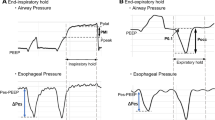

Demographics and clinical characteristics, arterial blood gases, the ratio between the partial pressure of oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2 ratio), blood lactate level, and clinical severity as assessed by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II were collected at the time of RICU admission (T0). At our center, the criteria for being referred to RICU to upgrade to NRS were in accordance with local protocols and included a peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) < 90% during conventional oxygen therapy with Venturi mask and/or the presence of respiratory rate (RR) > 25 breaths/m(bpm) and/or the presence of subjective respiratory distress. At T0, all patients underwent HFNC initiation whilst esophageal manometry, with a multifunctional nasogastric tube (NutriVent™, SIDAM, Mirandola, Italy) and according to a standardized protocol [4] was provided. The esophageal balloon was connected to a two-channel pressure monitoring system (OptiVent™, SIDAM, Mirandola, Italy) via a 100-cm polyurethane catheter. ΔPes and RR were recorded. A custom-made nasal pressure monitoring system was placed in the same nostril as the nasogastric tube, while the contralateral nostril was kept patent. The nasal pressure monitoring system was assembled with one hypoallergenic self-expanding foam ear plug (3 M Company, Saint Paul, Minnesota (MN), USA) with inserted a 16 Gauge polyurethane intravenous cannula. The self-expanding foam plug was placed in the nostril and modeled on the shape of the nasogastric tube to obtain a sealed tight closure of the external surface of the nostril, with HFNC placed only in the patent nostril. The nasal plug was connected to the second channel of the pressure monitoring system to obtain continuous measurement of ΔPnos. Once the nasal plug was placed and hermetic closure of the nostril was visually checked (T1), ΔPes and ΔPnos, as well as RR, were assessed and recorded simultaneously (see Fig. 1). To evaluate the influence of nasal breathing on the breathing pattern, changes in RR and ΔPes after nasal plug placement were assessed. In case of failure of HFNC, patients received a trial of escalation to non-invasive bilevel ventilation (NIV) if deemed indicated by the treating clinician, blinded to the study purposes. The criteria to upgrade to NIV were according to local protocols and included PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 100 mmHg and/or RR > 25 bpm and/or persistence of respiratory distress and dyspnea despite HFNC set at 60 L/min.

A Simultaneous positioning of esophageal catheter for ΔPes assessment and nasal plug made of hypoallergenic foam ear plug equipped with a 16 Gauge polyurethane intravenous cannula for ΔPnos measurements. The contralateral nostril was kept open. B, C Simultaneous assessment of ΔPnos and ΔPes during unsupported spontaneous breathing, showing in phase waveforms with a 196 ms time latency of ΔPnos over the onset of inspiratory effort captured by ΔPes. D, E Simultaneous assessment of ΔPnos and ΔPes, showing decremental inspiratory effort after NIV placement

After 24 h (T2), all patients underwent a further simultaneous assessment of ΔPes and ΔPnos, whatever the NRS in use (HFNC or NIV). Measurements at each timepoint were taken while in semi-recumbent position and breathing through the patent nostril with the mouth closed, following a 5-min period with a stable breathing pattern; measures were averaged from 3 subsequent breaths after stabilization. Data were sampled and stored at 100 Hz and processed a posteriori on the pressure monitoring system. The ratio of the ΔPes to the ΔPnos was computed and its average value was used to compute the estimated ΔPes based on the ΔPnos, according to the formula:

where k is the mean ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio in the overall cohort at T1, when all patients received HFNC.

Management of noninvasive respiratory support

Patients did not receive any sedation when using HFNC or NIV. HFNC was delivered with a high flow device (OptiflowTMand AIRVO™, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) through appropriately sized nasal cannulas. Flow delivery was initially set at 60 L/min and oxygen fraction at 50% and temperature at 37 °C then adjusted according to the patient’s tolerance; oxygen fraction was then titrated to target a SpO2 ≥ 92%.

NIV was delivered through an appropriately sized total face mask equipped with a dedicated output for probes (DiMax zero™, Dimar, Medolla, Italy) connected to a high-performance ventilator (GE Healthcare Engstrom Carestation™, GE Healthcare, Finland) in non-invasive pressure support mode, ensuring that mask-leak flow was below 20 L/min. The inspiratory trigger was set at 3 L/min and expiratory cycling at 25% of the inspiratory peak flow. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was initially set to 8 cmH2O and subsequently titrated to target a SpO2 > 92% with a delivered FiO2 < 0.7, while pressure support was started at 10 cmH2O, and then progressively adjusted targeting a tidal volume < 9.5 mL/kg of predicted body weight and a RR < 30 bpm. A heat and moisture exchanger (HME) with antimicrobial properties (Hygrobac, DAR, Mirandola, Italy) was connected between the Y-piece and the mask.

The decision to proceed to endotracheal intubation was taken according to local protocols by the attending staff, blinded to the results of the physiological parameters; criteria included: a) PaO2/FiO2 ratio unchanged or worsened or below 150 mmHg, b) worsening dyspnea persistence of RR > 35 bpm, c) the need to protect airways due to neurological deterioration or massive secretions, d) hemodynamic instability or major electrocardiographic abnormalities, e) gasping for air, psychomotor agitation requiring sedation, abdominal paradox movements.

Analysis plan

The correlation between ΔPes and ΔPnos at any study time and under different NRS was pre-specified as the study goal. The correlation between ΔPes and ΔPnos at different level of inspiratory effort (above or below the median baseline value of ΔPes) was also assessed. The distribution of the ratio between ΔPes and ΔPnos was further described. Normality of data was assessed with visual inspection of quantile–quantile plots, and data are reported as median [interquartile range, IQR], if not stated otherwise. Correlations were sought using Pearson’s R, between-groups differences with the Fisher’s and Mann–Whitney tests, as appropriate. Changes in RR and ΔPes before and after the insertion of the nasal probe and mouth closing were sought for using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. A sample size of at least 37 patients would have provided 90% power (1-β) to detect a correlation with R > 0.5 at an α level of 0.05. In a sensitivity analysis, we compared the agreement between ΔPes measured at T2 and ΔPes, estimated based on ΔPnos using the Bland–Altman method, to assess whether ΔPnos could serve as a surrogate of ΔPes. We further performed the analysis according to the type of NRS. In another sensitivity analysis, the differences of ΔPes and ΔPnos in patients that required endotracheal intubation versus those who were still under NIV or HFNC at 3 days from inclusion were assessed. Statistics were performed using R (version 4.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was assumed with two-tailed p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Sixty-one out of 160 consecutive patients admitted to the RICU in the considered time-lapse with de novo ARF and candidates to receive HFNC were enrolled. Of these 51 (83.6%) were diagnosed with COVID-19-related pneumonia while 10 had ARF of different etiology. Reasons for exclusion were: presence of chronic respiratory disease (N = 62), unavailability of research staff (N = 18), refusal to receive esophageal manometry (N = 19). The clinical and physiological characteristics of the study population at the study time points are shown in Table 1.

Effects of placement of nasal plug on the pattern of breathing

The insertion of the nasal plug did not change the pattern of breathing. The RR before and after insertion of the nasal plug was 25 [24–29] min−1 and 26 [24–30] min−1, respectively (p = 0.12), while the ΔPes was 12 [10–17] cmH2O and 12 [10–18] cmH2O (p = 0.29).

Correlation between ΔP es and ΔP nos

At T1, median ΔPes and ΔPnos were 12 [10–17] cmH2O and 5.6 [4.2–8.0] cmH2O, while at T2 were 7 [5–11] cmH2O and 3.0 [2.1–4.7] cmH2O, respectively. Patients with COVID-19 presented lower values of ΔPes and ΔPnos at T1 but not at T2 (Additional file 1: eTable 1). Figure 2 shows the correlation between ΔPes and ΔPnos at T1 (Panel A), with all patients receiving HFNC (R2 = 0.88, p < 0.001), and at T2 (Panel B, R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001), with 16 (26.2%) and 45 (73.8%) under HFNC and NIV, respectively. The correlation at T2 remained significant when analyzing separately patients receiving HFNC (R2 = 0.79, p < 0.001) or NIV (R2 = 0.95, p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: eFigure 1).

ΔP es to ΔP nos ratio

The distribution of the ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio is illustrated in Fig. 3 and was similar at T1 and T2 (2.20 [2.06–2.47] and 2.27 [2.11–2.50], p = 0.41). The ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio at T2 was similar in patients receiving HFNC versus NIV (2.23 [1.89–2.60] and 2.27 [2.15–2.50], respectively, p = 0.63). Moreover, the ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio at T1 was similar in patients with low versus high respiratory drive, defined as ΔPes > 12 cmH2O, (2.19 [2.06–2.50] and 2.20 [2.06–2.38], p = 0.67).

Sensitivity analyses

The mean ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio at T1 was 2.27 (standard deviation 0.44), and this value was used as multiplication factor to compute ΔPes, estimated from ΔPnos. Bland–Altman method at T2 showed a bias of 0.1 cmH2O and 95% limits of agreement, LoA, from -2.0 to 2.1 cmH2O (95.1% of measurements within LoA, Additional file 1: eFigure 2). Among patients receiving HFNC bias was 0.1 cmH2O and 95% LoA were from -2.1 to 2.3 cmH2O, while in patients receiving NIV bias was 0.0 and 95% LoA from -2.0 to 2.0 cmH2O.

Characteristics of patients who were intubated versus those still on NRS at day 3 are displayed in Additional file 1: eTable 2: at inclusion, ΔPes was 14.0 [10–18.0] and 12.0 [10.0–16.0] cmH2O (p = 0.53), while ΔPnos was 6.5 [4.3–8.4] and 5.6 [4.3–7.5] cmH2O (p = 0.76), respectively. At 24 h, patients who were further intubated had both higher ΔPes (15.0 [12.0–18.0] versus 7.0 [5.0–8.0] cmH2O, p < 0.001) and ΔPnos (7.5 [5.5–7.9] versus 3 [2.1–3.5] cmH2O, p < 0.001) as compared with those still under NRS.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that, in a population of patients with prevalently COVID-19-induced ARF, ΔPnos measured with closed mouth was highly correlated with ΔPes during non-assisted and assisted spontaneous breathing. The correlation between these two physiological variables showed persistence over time and low inter-patient variability regardless the application of HFNC or NIV. The assessment of ΔPnos did not affect inspiratory effort and respiratory rate during non-assisted spontaneous breathing. Moreover, ΔPnos and ΔPes after 24 h from NRS start resulted significantly higher in those patients that were subsequently intubated.

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the correlation between tidal changes of esophageal and nasal pressure in patients with ARF during spontaneous breathing. Previous studies already reported that Pes could be estimated by nasal pressure during a sniff test [12]. However, sniff represents a ballistic maneuver characterized by an acute increase in lung volume associated with a distortion of the chest wall, far from an isometric contraction [15]. Moreover, during volitional maximal inspiratory effort, the nasal valve of the patent nostril collapses, thus behaving as a Starling resistor. The pressure measured beyond the collapsed segment was found to closely reflect esophageal pressure with an average ratio Pes/Pnos of 1.05 during maximal sniff and of 1.09 during submaximal sniff, being Pnos always less than Pes. During tidal spontaneous breathing, instead, the posterior nasal valve remains open. When Pnos and Pes are measured during spontaneous breathing without the collapse of the posterior nasal valve, simultaneous pressure waveforms did not show phase difference, though the pressure ratio increased [12]. Based on these assumptions, Pnos swing is likely to mirror variation of Pes during spontaneous breathing. Indeed, our study confirmed that ΔPnos was highly correlated with ΔPes with a narrow range of ratio between the two values, irrespective of the strength of the inspiratory effort.

The distribution of ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio across our patient cohort was relatively consistent showing low inter-patient variability over time and under different type of support (Fig. 3). Given that ΔPnos reflects the Paw variation during tidal breathing, a potential interference in ΔPnos and ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio assessment following the application of positive inspiratory pressure could have been hypothesized. However, our results suggested that these measurements are not affected by the onset of positive pressure support ventilation. This might be because of the nasal plug that makes the nostril cavity an isolated anatomical structure not influenced by external pressure. This mechanism could explain why the ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio remains constant over time regardless the application of NIV. If confirmed in heterogeneous cohorts of patients with ARF, these preliminary data might suggest monitoring ΔPnos as a non-invasive and easy-to-perform surrogate measure of ΔPes to monitor the patient’s inspiratory effort during both assisted and not assisted spontaneous breathing.

The magnitude of inspiratory effort as assessed by esophageal manometry was not very high in our population. This might be because most of the enrolled patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 who displayed lower baseline values of ΔPes and ΔPnos. A recently published matched study by our group comparing patients with moderate to severe ARF [16], showed a relatively low activation of respiratory drive in COVID-19 patients during the early phase as compared with classical ARDS population. Despite the limited inspiratory effort observed during tidal breathing, patients in the present study still showed ΔPes levels above physiological ranges [17], thus reinforcing the suggestion of monitoring respiratory effort in patients with ARF and prompted to assisted breathing. Further, the implementation of NIV decreased the inspiratory effort which translated into a reduction of both ∆Pes and ∆Pnos at 24 h. According to a work from our group [4], a reduction of ∆Pes lower than 10 cmH2O after 2 h of NIV was found to be associated with a higher risk of NIV failure. Whether a threshold of ∆Pnos reduction following NIV could be determined as a predictor of intubation should be investigated in larger cohorts.

Although our study reported high correlation between ΔPes and ΔPnos, this technique may suffer from several physiological limitations that deserve discussion. First, previous studies regarding Sniff Nasal Inspiratory Pressure (SNIP) test showed that the transmission of pressure changes from the alveoli to the upper airways is altered in case of airflow limitation [18]. Moreover, SNIP was found to underestimate sniff ΔPes on average by 14% in patients with acute asthma and by 19% in patients with stable COPD [19, 20]. Despite ΔPnos and SNIP exhibit different physiological behaviors, dynamic hyperinflation may affect ΔPes/ΔPnos ratio also during spontaneous breathing. As we have excluded patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure and chronic obstructive respiratory disease, the present results should not be automatically extended to patients affected by significant dynamic intrinsic positive end expiratory pressure. Second, the measurement of ΔPnos during spontaneous breathing may be affected by the collapse of the posterior nasal valve induced by exaggerated respiratory drive [15, 21]. In this circumstance, tidal inspiratory breathing may become similar to an inspiratory effort against a closed airway, thus amplifying the pressure variation captured in the nostril. In this line, a device able to maintain the posterior nasal valve open could be useful to obtain reliable value of ΔPnos. Third, all the measurements were performed with patients asked to keep the mouth closed for the entire evaluation time. This task, however, might be difficult to accomplish in some clinical conditions (e.g., elevated respiratory drive, intense shortness of breath, lack of collaboration), and during severe nasal congestion or anatomical alterations of the nostrils. Moreover, although we did not measure the flow change induced by the ΔPnos equipment, it cannot be excluded that the insertion of the nasal plug would have modified the flow (and thus the positive pressure) delivered through HFNC. In this line, there is evidence that closing a nostril can modify the final flow delivered through HFNC, thus reducing the degree of positive pressure generated [22]. However, Bräunlich et al. [23] demonstrated that flow did not change by occluding one of the prongs of the nasal cannula. They also found that delivering pressure at 40 L/m slightly changed end positive airway pressure in this condition even leaving the contralateral nostril open. In addition, given that each measurement lasted for very limited time (5 min) and that we did not find significant changes in the breathing pattern (RR and ΔPes) after placing the Pnos equipment, we feel that the plug insertion did not significantly affect the impact provided by HFNC on patients’ respiratory drive. Also, our study population mainly included patients with COVID-19-related ARF, much reducing the generalizability of results. Finally, the clinical evidence provided by our investigation should be taken with caution as the study was not sufficiently empowered. In this line we believe that a different study design with a pre-calculated sample size would be needed to find a reliable threshold of ∆Pes and ∆Pnos able to predict the risk for intubation.

Conclusions

With this proof-of-concept physiological study we have showed that nasal pressure swing during spontaneous tidal breathing was highly correlated with esophageal pressure swing in patients with ARF. The ratio between these variables showed persistence over time and low inter-patient variability regardless the application of NRS. Should data be confirmed on larger studies and in heterogeneous populations with ARF, noninvasive and easy-to-use measurement of ΔPnos could be extended in different settings of care, thus implementing the respiratory effort monitoring of patients with ARF at impending risk of deterioration.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available at the Respiratory Disease Unit of the University Hospital of Modena, Italy.

Abbreviations

- ARF:

-

Acute respiratory failure

- NRS:

-

Non-invasive respiratory support

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation

- HFNC:

-

High flow nasal cannula

- PL :

-

Transpulmonary pressure

- ΔP es :

-

Esophageal pressure swings

- ΔP nos :

-

Nasal pressure swings

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2

- COVID-19:

-

SARS-CoV-2-induced Disease

- RICU:

-

Respiratory Intensive Care Unit

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PS:

-

Pressure support

- PT-PCR:

-

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- BPM:

-

Breaths per minute

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- FiO2 :

-

Fraction of oxygen

- ETI:

-

Endotracheal intubation

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SNIP:

-

Sniff Nasal Inspiratory Pressure

- ΔP aw :

-

Airway pressure swings

References

Yoshida T, Amato MBP, Grieco DL, Chen L, Lima CAS, Roldan R, Morais CCA, Gomes S, Costa ELV, Cardoso PFG, Charbonney E, Richard J-CM, Brochard L, Kavanagh BP. Esophageal manometry and regional transpulmonary pressure in lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:1018–26.

Battaglini D, Robba C, Ball L, Leme Silva P, Ferreira Cruz F, Pelosi P, Rieken Macedo Rocco P. Mechanisms of patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI) in COVID-19: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth 2021 (in press)

Yoshida T, Grieco DL, Brochard L, Fujino Y. Patient self-inflicted lung injury and positive end-expiratory pressure for safe spontaneous breathing. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26:59–65.

Tonelli R, Fantini R, Tabbì L, Castaniere I, Pisani L, Pellegrino MR, Della Casa G, D’Amico R, Girardis M, Nava S, Clini EM, Marchioni A. Early Inspiratory effort assessment by esophageal manometry predicts noninvasive ventilation outcome in de novo respiratory failure. A pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:558–67.

Bellani G, Grasselli G, Teggia-Droghi M, Mauri T, Coppadoro A, Brochard L, Pesenti A. Do spontaneous and mechanical breathing have similar effects on average transpulmonary and alveolar pressure? A clinical crossover study. Crit Care. 2016;20:142.

Gregoretti C, Pisani L, Cortegiani A, Ranieri VM. Noninvasive ventilation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Clin. 2015;31:435–57.

Akoumianaki E, Maggiore SM, Valenza F, Bellani G, Jubran A, Loring SH, Pelosi P, Talmor D, Grasso S, Chiumello D, Guérin C, Patroniti N, Ranieri VM, Gattinoni L, Nava S, Terragni P-P, Pesenti A, Tobin M, Mancebo J, Brochard L. The application of esophageal pressure measurement in patients with respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:520–31.

Mojoli F, Torriglia F, Orlando A, Bianchi I, Arisi E, Pozzi M. Technical aspects of bedside respiratory monitoring of transpulmonary pressure. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:377.

Walamies MA. Perception of esophageal manometry. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:46–9.

Franco C, Facciolongo N, Tonelli R, Dongilli R, Vianello A, Pisani L, Scala R, Malerba M, Carlucci A, Negri EA, Spoladore G, Arcaro G, Tillio PA, Lastoria C, Schifino G, Tabbì L, Guidelli L, Guaraldi G, Ranieri VM, Clini E, Nava S. Feasibility and clinical impact of out-of-ICU noninvasive respiratory support in patients with COVID-19-related pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(5):2002130. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02130-2020.

Tonelli R, Marchioni A, Tabbì L, Fantini R, Busani S, Castaniere I, Andrisani D, Gozzi F, Bruzzi G, Manicardi L, Demurtas J, Andreani A, Cappiello GF, Samarelli AV, Clini E. Spontaneous breathing and evolving phenotypes of lung damage in patients with COVID-19: review of current evidence and forecast of a new scenario. J Clin Med. 2021;10:975.

Koulouris N, Mulvey DA, Laroche CM, Sawicka EH, Green M, Moxham J. The measurement of inspiratory muscle strength by sniff esophageal, nasopharyngeal, and mouth pressures. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:641–6.

Marazzini L, Cavestri R, Gori D, Gatti L, Longhini E. Diffference between mouth and esophageal occlusion pressure during CO2 rebreathing in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:1027–33.

Baydur A, Behrakis PK, Zin WA, Jaeger M, Milic-Emili J. A simple method for assessing the validity of the esophageal balloon technique. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:788–91.

Héritier F, Rahm F, Pasche P, Fitting JW. Sniff nasal inspiratory pressure. A noninvasive assessment of inspiratory muscle strength. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1678–83.

Tonelli R, Busani S, Tabbì L, Fantini R, Castaniere I, Biagioni E, Mussini C, Girardis M, Clini E, Marchioni A. Inspiratory effort and lung mechanics in spontaneously breathing patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19: a matched control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202104-1029LE.

Grieco DL, Menga LS, Eleuteri D, Antonelli M. Patient self-inflicted lung injury: implications for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and ARDS patients on non-invasive support. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85(9):1014–23. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13418-9.

Fitting J-W. Sniff nasal inspiratory pressure: simple or too simple? Eur Respir J. 2006;27:881–3.

Stell IM, Polkey MI, Rees PJ, Green M, Moxham J. Inspiratory muscle strength in acute asthma. Chest. 2001;120:757–64.

Uldry C, Janssens JP, de Muralt B, Fitting JW. Sniff nasal inspiratory pressure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1292–6.

Spinelli E, Mauri T, Beitler JR, Pesenti A, Brodie D. Respiratory drive in the acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathophysiology, monitoring, and therapeutic interventions. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:606–18.

Luo JC, Lu MS, Zhao ZH, Jiang W, Xu B, Weng L, Li T, Du B. Positive end-expiratory pressure effect of 3 high-flow nasal cannula devices. Respir Care. 2017;62(7):888–95. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.05337.

Bräunlich J, Mauersberger F, Wirtz H. Effectiveness of nasal highflow in hypercapnic COPD patients is flow and leakage dependent. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0576-x.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank professional editor Colin Woodham (Alpha Science Editors) for language editing.

Funding

No funding available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM explored and elucidated the physiological assumptions of the study, defined the study design and procedures, and was responsible for the measurement and interpretation of physiological variables. RF developed the prototype for nasal pressure measurements, enrolled the patients and wrote the paper. RT and LT designed the study, enrolled the patients, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. CC, MV, CN, IC, LM and FG made substantial contributions to the literature review, data collection, and paper writing. LB and AC reviewed the literature, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, and produced the figures. GB, BB and MRP reviewed and edited the manuscript. CG, EB, SB, MG, PP and EC designed the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. RT and AC have contributed equally to the conception and realization of the study and should be considered both as first authors. LB and EC share the senior authorship. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval from the Area Vasta Emilia Nord Ethics committee was obtained (protocol number 4485/C.E., document 266/16). Written informed consent to participate was obtained by all patients enrolled or their relatives, when appropriate.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained by all patients enrolled.

Competing interests

Authors have no competing interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in competition with the subject, matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. Prof. Andrea Cortegiani is an Advisory Board member for Critical Care.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: eTable 1.

Esophageal and nasal pressure swings according to acute respiratory failure etiology. Data are presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). eFigure 1. Pearson’s R showing correlations between ΔPes and ΔPnos at 24 hours after splitting the study population according to the NRS received. eFigure 2. Bland-Altman analysis assessing the agreement between ΔPes measured with esophageal manometry and estimated based on ΔPnos (ΔPes, estimated) and computed as k·ΔPnos, where k is the average ratio of ΔPes to ΔPnos measured at baseline. At T2 Bland-Altman methods showed a bias of 0.1 cmH2O and 95% limits of agreement, LoA, from −2.0 to 2.1 cmH2O (95.1% of measurements within LoA). Among patients receiving HFNC bias was 0.1 cmH2O and 95% LoA were from −2.1 to 2.3 cmH2O, while in patients receiving NIV bias was 0.0 and 95% LoA from −2.0 to 2.0 cmH2O. eTable 2. General and clinical characteristics of the study population according to respiratory support at day 3. Data are presented as number (n) and percentage for dichotomous values or median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous values.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tonelli, R., Cortegiani, A., Marchioni, A. et al. Nasal pressure swings as the measure of inspiratory effort in spontaneously breathing patients with de novo acute respiratory failure. Crit Care 26, 70 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03938-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03938-w