Abstract

Background

Septic shock is associated with decreased vasopressor responsiveness. Experimental data suggest that central alpha2-agonists like dexmedetomidine (DEX) increase vasopressor responsiveness and reduce catecholamine requirements in septic shock. However, DEX may also cause hypotension and bradycardia. Thus, it remains unclear whether DEX is hemodynamically safe or helpful in this setting.

Methods

In this post hoc subgroup analysis of the Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation (SPICE III) trial, an international randomized trial comparing early sedation with dexmedetomidine to usual care in critically patients receiving mechanical ventilation, we studied patients with septic shock admitted to two tertiary ICUs in Australia and Switzerland. The primary outcome was vasopressor requirements in the first 48 h after randomization, expressed as noradrenaline equivalent dose (NEq [μg/kg/min] = noradrenaline + adrenaline + vasopressin/0.4).

Results

Between November 2013 and February 2018, 417 patients were recruited into the SPICE III trial at both sites. Eighty-three patients with septic shock were included in this subgroup analysis. Of these, 44 (53%) received DEX and 39 (47%) usual care. Vasopressor requirements in the first 48 h were similar between the two groups. Median NEq dose was 0.03 [0.01, 0.07] μg/kg/min in the DEX group and 0.04 [0.01, 0.16] μg/kg/min in the usual care group (p = 0.17). However, patients in the DEX group had a lower NEq/MAP ratio, indicating lower vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP. Moreover, on adjusted multivariable analysis, higher dexmedetomidine dose was associated with a lower NEq/MAP ratio.

Conclusions

In critically ill patients with septic shock, patients in the DEX group received similar vasopressor doses in the first 48 h compared to the usual care group. On multivariable adjusted analysis, dexmedetomidine appeared to be associated with lower vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP.

Trial registration

The SPICE III trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01728558).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In septic shock, sympathetic activation and release of endogenous catecholamines are necessary physiological mechanisms to maintain adequate tissue perfusion [1]. However, excessive release of endogenous catecholamines in combination with exogenous catecholamines can cause sympathetic overstimulation with detrimental effects on organ function and patient outcomes [2]. Sympathetic overstimulation may also cause downregulation and desensitization of alpha-adrenergic receptors. Such catecholamine hyposensitivity may also contribute to hemodynamic instability and poor outcomes [3, 4].

In experimental animal models of sepsis, high doses of central alpha-2-agonists like clonidine and dexmedetomidine increase vasopressor responsiveness [5]. Moreover, even in non-septic patients, alpha-2-agonists are associated with lower vasopressor requirements [6, 7], increased arterial blood pressure, and enhanced baroreceptor response [8, 9]. However, significant hemodynamic side effects of dexmedetomidine can also occur such as hypotension and bradycardia [10].

In the Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation (SPICE III) Trial, critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation received early dexmedetomidine for primary sedation or usual sedation [11]. The study design and randomization scheme provided the unique opportunity to explore the hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine in patients with septic shock. Thus, in this two-center retrospective subgroup analysis of patients with septic shock included in the SPICE III trial, we assessed the physiological effects of dexmedetomidine on vasopressor requirements and blood pressure in the first 48 h after randomization.

Methods

The SPICE III trial was a randomized, open-label trial conducted at 74 sites in eight countries [11]. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices and was approved by the institutional review board at participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained for all patients. The study design, protocol, and statistical analysis plan have been previously published [12]. Critically ill adults (18 years or older) receiving mechanical ventilation for less than 12 h in the intensive care unit (ICU) were randomized to receive dexmedetomidine as the sole or primary sedative or to receive usual care (propofol, midazolam, or other sedatives), if they were expected to remain on invasive ventilatory support for longer than the next calendar day. The primary outcome of the SPICE III trial was the rate of death from any cause at 90 days.

Study design

The present study is an exploratory, post hoc, retrospective subgroup analysis of patients with septic shock who were enrolled in the SPICE trial III. The subgroup analysis was performed at two of the participating centers, the Austin Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, and the University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland, and was approved by the ethics committees at both sites (approval number LNR/15/Austin/391 and KEK-ID2018-00746).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In addition to the abovementioned inclusion criteria of the SPICE III trial, patients had to meet all the following criteria to be eligible for this subgroup analysis: documented (or strong suspicion of) infection with at least 2 clinical signs of inflammation (temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C, heart rate > 90/min, respiratory rate > 20/min, or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg, white cell count > 12 × 109/l or < 4 × 109/l or > 10% immature neutrophils), and administration of vasopressors or inotropes prior to randomization and for a cumulative duration of ≥ 4 h to maintain blood pressure targets set by the treating clinician.

In addition to the exclusion criteria of the SPICE III trial, we excluded patients meeting our inclusion criteria more than 24 h before randomization. A detailed list of all inclusion and exclusion criteria is given in the supplementary appendix. To reflect the effects of the intervention (dexmedetomidine or usual care) unaffected by protocol deviations or non-adherence, we performed a per-protocol analysis excluding patients who did not receive the allocated sedation regimen and patients whose treatment goal was changed to end-of-life care within the first 48 h after randomization.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome was the median vasopressor dose in the first 48 h after randomization, expressed as noradrenaline equivalent dose (NEq). We calculated NEq using the method described by Khanna and co-workers [13] as

to account for the different vasopressors used at the two study sites. Secondary outcomes included cumulative and peak NEq dose, change in NEq dose from baseline to peak dose, and the ratio of NEq to MAP (NEq/MAP), to account for different blood pressure targets set by the treating physician. Exploratory outcomes included cumulative duration of vasopressor support, ICU and hospital mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay.

Data collection

Data collection was performed using existing ICU-based electronic databases (Cerner Electronic Health Record, North Kansas City, MO, USA, and Centricity Critical Care, Clinisoft, GE Healthcare Europe, Helsinki, Finland) and medical record review. Whenever possible, data were downloaded from electronic medical records. Continuous measurements, recorded at minimum once every 2 min, were resampled to obtain hourly median values of hemodynamic data, sedative and vasoactive drug doses for the first 48 h after randomization. Arterial blood pressure was monitored invasively in all patients. Where manual data collection was necessary, it was performed using double data entry or cross-checked by a second investigator. Demographic data and patient-centered outcomes were obtained from the SPICE III database.

Statistical analysis

Data was initially assessed for normality and log-transformed where appropriate. Group comparisons were performed using chi-square tests for equal proportion, Student’s t tests for normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests otherwise, with results presented as numbers (%), means (standard deviations), or medians (interquartile range), respectively. Longitudinal analysis was performed using mixed linear modeling fitting main effects for treatment, time, and an interaction between the two to determine if groups behaved differently over time. Multivariable longitudinal sensitivity analyses were performed firstly adjusting for baseline imbalance and known covariates (admission diagnosis, hospital site, ratio of noradrenaline equivalent over mean arterial pressure at baseline, continuous renal replacement therapy, age, administration of hydrocortisone, and presence of liver cirrhosis) and then secondly adjusting for the same covariates but with treatment group replaced by actual dexmedetomidine dosage. Comparison of proportions for secondary outcomes was determined using logistic regression with results presented as odds ratios (95%CI). Differences for continuous secondary outcomes were determined using quantile regression with results presented as difference of medians (95%CI). To account for the competing risk of death, durations of vasopressor support and ventilation are presented as cumulative incidence functions with censoring for death and comparison using Grey’s test. Time to death was displayed using Kaplan-Meier curves with comparison using a log-rank test. All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and a two-sided p value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Sample size

With a minimum of 38 patients per group, this study had > 90% power (2-sided p value) to detect a difference in noradrenaline requirement equivalent to 75% of one standard deviation. Across the range of the data, a difference of this magnitude approximately equates to a 20% difference, which is perceived to be of clinical importance.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

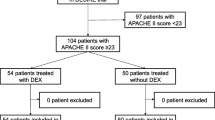

Between November 2013 and February 2018, 417 patients were recruited in the SPICE III trial at both sites (196 patients at the Austin Hospital and 221 patients at the University Hospital of Bern). Among those who provided written informed consent, 87 patients fulfilled our inclusion criteria of septic shock. After excluding two patients from each group who did not receive the assigned sedation, 83 patients were included in the analysis. Of these, 44 (53%) had been assigned to receive dexmedetomidine (DEX group) and 39 (47%) to usual care. Fifty-seven patients (68.7%) were male, with a mean age of 65.4 years, and a mean pre-randomization APACHE II score of 25.1. Patient characteristics and treatment at randomization were similar in the two groups, except for a higher creatinine level and higher coagulation component of the SOFA score in the usual care group (Table 1).

Clinical outcomes

In the first 48 h after randomization, there was no significant difference in median NEq dose between the DEX group and the usual care group (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Similarly, we found no significant difference in cumulative NEq dose, peak NEq dose, and relative change in NEq from baseline to peak dose between the two groups.

Over the first 48 h, patients in the DEX group had a numerically higher MAP (Fig. 2), although the differences did not reach statistical significance. However, vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP (expressed by the NEq/MAP ratio) were lower in the DEX group compared to the usual care group (ratio of difference in geometric means 1.74 [1.02, 2.95], p = 0.04). This result remained significant when adjusted for admission diagnosis, hospital site, baseline NEq/MAP ratio, continuous renal replacement therapy, age, administration of hydrocortisone, and liver cirrhosis (ratio of adjusted difference in geometric means 1.44 [1.07–1.95], p = 0.02) (Fig. 3).

Adjusted ratio of noradrenaline equivalents divided by MAP (NEq/MAP ratio) in the first 48 h after randomization. Adjusted for admission diagnosis, hospital site, baseline NEq/MAP ratio, continuous renal replacement therapy, age, administration of hydrocortisone and presence of liver cirrhosis. NEq/MAP: Noradrenaline equivalents to mean arterial pressure ratio (a higher ratio indicates higher vasopressor need to maintain a certain MAP). Data are presented as geometric means and 95% confidence intervals, overall group difference p = 0.02

On multivariable sensitivity analysis adjusting for actual dexmedetomidine dosage, the results were consistent with the above findings: Dexmedetomidine dose was associated with a reduction in the NEq/MAP ratio (parameter estimate of − 0.17 +/− 0.07; p = 0.02), indicating lower vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP. The NEq/MAP ratio was significantly greater in patients treated in Australia, in patients not on continuous renal replacement therapy, without liver disease, without portal hypertension, or with a renal or cardiovascular APACHE admission category (Table 3).

There was no significant difference in ICU and hospital length of stay, number of patients alive and vasopressor-free at 48 h, time to vasopressor weaning, duration of invasive ventilation, and mortality between the two groups (Table 2 and Figs. 4, 5, and 6). Unlike the SPICE III trial, in the present sub-study, we found no significant difference in outcomes when comparing age groups above and below the median age (63.7 years) (Table S4).

Process of care

Nineteen patients (43.2%) in the DEX group and 16 patients (41.0%) in the usual care group received hydrocortisone (p = 0.84). Vasoactive drugs were discontinued within 48 h of randomization in 21 (47.7%) patients in the DEX group and 21 (53.8%) patients in the usual care group (p = 0.58). Patients in the DEX group received significantly lower doses of propofol and less midazolam. However, they received similar doses of opioids (Table S1). The median Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) score on study day 1 was − 4 [− 4, − 2] in the DEX group and − 4 [− 4, − 3] in the usual care group (p = 0.42). There was no significant difference regarding treatment with vasopressors, inotropes, and hydrocortisone between patients treated before and after the publication of the 2016 sepsis guidelines (Table S5).

Adverse events

Adverse events were prospectively collected during the original SPICE III trial. Due to the un-blinded study design, events were reported by site investigators but not systematically collected in both groups. Bradycardia was defined as heart rate < 55 beats per minute requiring intervention (e.g., pacing, pharmacological support, or modification of dexmedetomidine or other medication doses). Hypotension was defined as hypotension which is clinically significant in the Principal Investigator’s opinion. In our cohort, hypotension was reported in seven (15.9%) patients in the DEX group and one (2.6%) patient in the usual care group (p = 0.04). Bradycardia occurred in five patients (11.4%), all were from the DEX group (p = 0.06). Serious adverse events occurred in two patients in the DEX group (hypotension) and one patient in the usual care group (cardiac arrest, survived) (Table S2).

Discussion

In this exploratory post hoc retrospective subgroup analysis of ICU patients with septic shock requiring mechanical ventilation, patients receiving early sedation with dexmedetomidine as the primary sedative agent had similar vasopressor requirements in the first 48 h compared to usual care. On adjusted exploratory analysis, dexmedetomidine appeared to be associated with lower vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP.

As alpha-2 agonist, dexmedetomidine may increase the risk of hypotension and bradycardia [14, 15] and, in patients with septic shock, this may be both dangerous and harmful. However, experimental data also suggest that dexmedetomidine can be administered in septic shock and may even have catecholamine-sparing effects [5, 16,17,18,19,20,21]. Our findings are consistent with such experimental observations. In a subgroup analysis of septic patients (n = 63) from the Maximizing Efficacy of Targeted Sedation and Reducing Neurological Dysfunction (MENDS) trial, the incidence of hypotension, vasopressor use, and cardiac arrhythmias were similar in both groups (dexmedetomidine vs. lorazepam-based sedation), but the trial was not powered to detect a difference in cardiovascular outcomes [22]. A retrospective study by Nelson et al. compared clinically significant hemodynamic events in adults with septic shock receiving dexmedetomidine (n = 37) or propofol (n = 35) (Nelson 2018). Dexmedetomidine was not associated with more episodes of hypotension or bradycardia (29.7% vs. 31.4, p = 0.99) [23]. A prospective open-label crossover study in 38 patients with septic shock found a reduction of catecholamine requirements after switching from propofol to dexmedetomidine [18]. However, both studies included resuscitated patients on stable vasopressor doses for at least 2 h, and, in the latter study, data collection was limited to the first 8 h.

In animal models of sepsis, high doses of central alpha2-agonists increase vasopressor responsiveness [5]. Moreover, dexmedetomidine reduces noradrenaline requirements and maintains renal function in experimental septic acute kidney injury [17]. In healthy volunteers, dexmedetomidine decreases plasma levels of both noradrenaline and adrenaline [9]. The mechanisms behind these findings are not fully understood, and different hypotheses have been proposed to explain how alpha-2 agonists improve vasopressor responsiveness. One hypothesis is that alpha-2 agonists have the potential to prevent downregulation and/or lead to resensitization of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors by reducing the sympathetic outflow and the release of endogenous catecholamines in sepsis [4, 24]. Presumably, lowering endogenous noradrenaline levels improves the action of exogenous noradrenaline on vascular α-1 receptors [5]. The second hypothesis suggests an anti-inflammatory effect of DEX [25,26,27,28,29,30], mediated by the vagus nerve and the so-called cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway [31], a neural circuit that responds to and regulates the inflammatory response via the release of acetylcholine [8]. Finally, α-2 agonists may act via local vascular mechanisms on vascular smooth muscle cells [32] and the presynaptic action of α-2 agonists could, by reducing the release of endogenous noradrenaline, lead to an upregulation of postsynaptic α-1 receptors [5].

Our findings that sedation with dexmedetomidine does not increase vasopressor requirements in the first 48 h imply that dexmedetomidine may be used in patients with septic shock without worsening hemodynamic instability. Our findings neither support nor refute the hypothesis that dexmedetomidine has a catecholamine-sparing effect in this setting, although the association of dexmedetomidine with a lower NEq/MAP ratio points towards lower overall vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP. However, because we did not pre-specify this outcome and we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, this finding should be considered exploratory. Moreover, the percentage of RASS scores below − 2 on study day 1 was higher in the usual care group compared to the DEX group, indicating deeper sedation in the usual care group in the first 24 h. This may, at least in part, explain the lower vasopressor requirements in the DEX group. Notwithstanding these limitations, the observed trend towards higher MAP in the DEX group and its potential to lower vasopressor requirements support further explorations of dexmedetomidine-based sedation in mechanically ventilated patients with septic shock.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, we studied patients in septic shock randomly assigned to one of two treatment strategies (early DEX sedation vs. usual care) and analyzed the hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine compared to usual care sedation. Second, we obtained granular and detailed data from two academic ICUs on hemodynamic parameters, level of sedation, dose, and duration of vasoactive and sedative drugs. Third, we used data from the original SPICE III database, electronic patient health records (whenever possible), and double data entry for manually collected data, to minimize the risk of ascertainment bias.

Our study is a retrospective exploratory subgroup analysis, not prespecified in the SPICE III study protocol and, therefore, comes with inevitable limitations. All findings must be interpreted strictly as hypothesis generating. However, due to the existing clinical equipoise regarding benefits and risks of using dexmedetomidine in patients with septic shock, our results have incremental value in adding to our understanding of the hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine in such patients. Because the goal of this investigation was to explore the effects of dexmedetomidine on hemodynamic parameters and vasopressor use, we excluded two patients in each group who did not receive the assigned treatment and opted for a per-protocol instead of an intention-to-treat analysis. However, baseline characteristics of patients included were similar, and it is unlikely that including these four patients would have materially altered our results. Hemodynamic management was not dictated by protocol and, as management of vasodilatory shock differs with respect to utilization of steroids and vasopressors [33], we cannot exclude a bias related to the open-label design of the SPICE III study or due to clinical preferences. However, by calculating the NEq/MAP ratio we sought to account for the different types of vasopressors used and for the individual MAP targets prescribed by the treating clinicians; the proportion of patients treated with hydrocortisone was similar in both groups, and we included hydrocortisone in our multivariable adjusted analysis. Finally, DEX was associated with more episodes of bradycardia and hypotension, as already reported in the SPICE trial (11). Thus, although the overall effect of using DEX as the primary sedating agent in mechanically ventilated patients with septic shock appears to improve the vasopressor dose to MAP ratio in the first 48 h, in some patients it may precipitate unwanted hemodynamic changes. Accordingly, caution should be exercised when starting the infusion and in administering this agent in patients at risk of bradycardia.

Conclusion

In critically ill patients with septic shock, compared to usual care, patients receiving early sedation with dexmedetomidine as the primary sedative agent had similar vasopressor requirements in the first 48 h compared to usual care. On multivariable adjusted analysis, dexmedetomidine appeared to be associated with lower vasopressor requirements to maintain the target MAP. These findings should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis generating. However, they provide a rationale for further randomized trials evaluating dexmedetomidine in patients with septic shock.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are part of the SPICE III trial and, therefore, not publicly available. De-identified data that underly the reported results will be made available to researchers with a defined protocol and analysis plan, after approval by Monash University, Melbourne, the University of Bern, Switzerland, and the SPICE III Management Committee (Email to yahya.shehabi@monash.edu or y.shehabi@unsw.edu.au).

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DEX:

-

Dexmedetomidine

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- NEq:

-

Noradrenaline equivalents

- NEq/MAP:

-

Noradrenaline equivalents to MAP ratio

- RASS:

-

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SPICE:

-

Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation

References

Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):776–87.

Ferreira J. The theory is out there: the use of ALPHA-2 agonists in treatment of septic shock. Shock. 2018;49(4):358–63.

Parrillo JE. Pathogenetic mechanisms of septic shock. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(20):1471–7.

Pichot C, Geloen A, Ghignone M, Quintin L. Alpha-2 agonists to reduce vasopressor requirements in septic shock? Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):652–6.

Geloen A, Chapelier K, Cividjian A, Dantony E, Rabilloud M, May CN, Quintin L. Clonidine and dexmedetomidine increase the pressor response to norepinephrine in experimental sepsis: a pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):e431–8.

Parlow JL, Sagnard P, Begou G, Viale JP, Quintin L. The effects of clonidine on sensitivity to phenylephrine and nitroprusside in patients with essential hypertension recovering from surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88(6):1239–43.

Herr DL, Sum-Ping ST, England M. ICU sedation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: dexmedetomidine-based versus propofol-based sedation regimens. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17(5):576–84.

Inomata SNT, Kihara S, et al. Enhancement of pressor response to intravenous phenylephrine following oral clonidine medi- cation in awake and anaesthetized patients. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:119–25.

Ebert TJ, Hall JE, Barney JA, Uhrich TD, Colinco MD. The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of dexmedetomidine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2000;93(2):382–94.

Sanders RD, Maze M. Alpha2-adrenoceptor agonists. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8(1):25–33.

Shehabi Y, Howe BD, Bellomo R, Arabi YM, Bailey M, Bass FE, Bin Kadiman S, McArthur CJ, Murray L, Reade MC, et al. Early sedation with dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2506–17.

Shehabi Y, Forbes AB, Arabi Y, Bass F, Bellomo R, Kadiman S, Howe BD, McArthur C, Reade MC, Seppelt I, et al. The SPICE III study protocol and analysis plan: a randomised trial of early goaldirected sedation compared with standard care in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Resusc. 2017;19(4):318–26.

Khanna A, English SW, Wang XS, Ham K, Tumlin J, Szerlip H, Busse LW, Altaweel L, Albertson TE, Mackey C, et al. Angiotensin II for the treatment of Vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):419–30.

Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, Ceraso D, Wisemandle W, Koura F, Whitten P, Margolis BD, Byrne DW, Ely EW, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(5):489–99.

Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, Bratty JR, Takala J. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1151–60.

Lankadeva YR, Booth LC, Kosaka J, Evans RG, Quintin L, Bellomo R, May CN. Clonidine restores pressor responsiveness to phenylephrine and angiotensin II in ovine sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(7):e221–9.

Lankadeva YR, Ma S, Iguchi N, Evans RG, Hood SG, Farmer DGS, Bailey SR, Bellomo R, May CN. Dexmedetomidine reduces norepinephrine requirements and preserves renal oxygenation and function in ovine septic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2019;96(5):1150–61.

Morelli A, Sanfilippo F, Arnemann P, Hessler M, Kampmeier TG, D'Egidio A, Orecchioni A, Santonocito C, Frati G, Greco E, et al. The effect of propofol and dexmedetomidine sedation on norepinephrine requirements in septic shock patients: a crossover trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(2):e89–95.

Quintin L. Alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonists and sepsis: improved survival? Crit Care. 2010;14(4):429 author reply 429.

Geloen A, Pichot C, Leroy S, Julien C, Ghignone M, May CN, Quintin L. Pressor response to noradrenaline in the setting of septic shock: anything new under the sun-dexmedetomidine, clonidine? A minireview. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:863715.

Hernandez G, Tapia P, Alegria L, Soto D, Luengo C, Gomez J, Jarufe N, Achurra P, Rebolledo R, Bruhn A, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine and esmolol on systemic hemodynamics and exogenous lactate clearance in early experimental septic shock. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):234.

Pandharipande PP, Sanders RD, Girard TD, McGrane S, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, Herr DL, Maze M, Ely EW, investigators M. Effect of dexmedetomidine versus lorazepam on outcome in patients with sepsis: an a priori-designed analysis of the MENDS randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):R38.

Nelson KM, Patel GP, Hammond DA. Effects from continuous infusions of dexmedetomidine and propofol on hemodynamic stability in critically ill adult patients with septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066618802269.

Mermet C, Quintin L. Effect of clonidine on catechol metabolism in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: an in vivo electrochemical study. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;204(1):105–7.

Gu J, Chen J, Xia P, Tao G, Zhao H, Ma D. Dexmedetomidine attenuates remote lung injury induced by renal ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(10):1272–8.

Gu J, Sun P, Zhao H, Watts HR, Sanders RD, Terrando N, Xia P, Maze M, Ma D. Dexmedetomidine provides renoprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R153.

Hofer S, Steppan J, Wagner T, Funke B, Lichtenstern C, Martin E, Graf BM, Bierhaus A, Weigand MA. Central sympatholytics prolong survival in experimental sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13(1):R11.

Taniguchi T, Kidani Y, Kanakura H, Takemoto Y, Yamamoto K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on mortality rate and inflammatory responses to endotoxin-induced shock in rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(6):1322–6.

Taniguchi T, Kurita A, Kobayashi K, Yamamoto K, Inaba H. Dose- and time-related effects of dexmedetomidine on mortality and inflammatory responses to endotoxin-induced shock in rats. J Anesth. 2008;22(3):221–8.

Wu Y, Liu Y, Huang H, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Lu F, Zhou C, Huang L, Li X, Zhou C. Dexmedetomidine inhibits inflammatory reaction in lung tissues of septic rats by suppressing TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:562154.

Xiang H, Hu B, Li Z, Li J. Dexmedetomidine controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Inflammation. 2014;37(5):1763–70.

Shimamura K, Toba M, Kimura S, Ohashi A, Kitamura K. Clonidine induced endothelium-dependent tonic contraction in circular muscle of the rat hepatic portal vein. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2006;42(2–3):63–74.

Abril MK, Khanna AK, Kroll S, McNamara C, Handisides D, Busse LW. Regional differences in the treatment of refractory vasodilatory shock using Angiotensin II in High Output Shock (ATHOS-3) data. J Crit Care. 2019;50:188–94.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marianne Roth and Roy Lanz from the Department of Intensive Care Medicine at the University of Bern for their support with data collection.

SPICE III Management committee: Yahya Shehabi (Chair), Yaseen Arabi, Frances Bass, Rinaldo Bellomo, Simon Erickson, Belinda Howe (Senior Project Manager), Suhaini Kadiman, Colin McArthur, Lynnette Murray, Michael Reade, Ian Seppelt, Jukka Takala, Steve A Webb, Matthew P Wise.

SPICE III Writing committee: Yahya Shehabi, MD, PhD, Belinda Howe, RN, BAppScNur, MPH, Rinaldo Bellomo, MD, PhD, Yaseen M Arabi, MD, Michael J Bailey, PhD, MSc, BSc (Hons), Frances Bass, BN, GCCC, Suhaini Kadiman, MD, Colin McArthur MBChB, FANZCA, FCICM, Lynnette Murray BAppSci, FAIMS, Michael Reade, MBBS, MPH, PhD, Ian Seppelt, MBBS, BScMed, Jukka Takala, MD, PhD, Steve A Webb, MD, PhD, Matthew P Wise, MD, D. Phil, for the SPICE III investigators, and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group.

SPICE III Affiliations of the writing committee: Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, Monash University, Melbourne, (MB, RB, BH, CM, LM, SAW); Monash University, School of Clinical Sciences, Melbourne (YS), Monash Health, Melbourne (YS); University of New South Wales, Clinical School of Medicine, Sydney (YS); King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences and King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (YA); King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (YA); Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney (FB); The George Institute for Global Health (FB); Austin Health, Melbourne (RB); National Heart Institute, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (SK); Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand (CM); University of Queensland, Brisbane (MR); Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital, Brisbane (MR); Australian Defence Force, Brisbane (MR); Sydney Medical School – Nepean, University of Sydney, Sydney (IS); Dept of Clinical Medicine, Macquarie University, (IS); Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland (JT); University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland (JT); St John of God Subiaco, Subiaco (SAW); University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, United Kingdom (MPW); (all in Australia unless specified).

SPICE III Study coordinating center: The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre (ANZIC-RC), School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne. Michael J Bailey, Belinda D. Howe, Lynette Murray, Vanessa Singh.

Funding

The SPICE III trial was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the National Heart Institute Foundation of Malaysia. Pfizer and Orion Pharma provided dexmedetomidine to trial sites. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript of the present sub-study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

LC and NL contributed equally to this article as co-primary authors. Concept and design: LC, NL, LP, HY, RB, JT. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data: LC, NL, MB, BH, ASM, HKP, LP, HY, GME, TMM. Drafting of the manuscript: LC, NL, ASM, MB, SMJ, JT, RB. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: LC, NL, ASM, MB, YS, BH, GME, TMM, JT, SMJ, RB. Statistical analysis: MB, NL, LC. Administrative, technical, or material support: YS, BH, AS, TMM, HKP, LP, HY, GME. Supervision: SMJ, JT, RB, YS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The SPICE III trial complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices and was approved by the institutional review board at participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained for all patients. The present subgroup analysis was performed at the Austin Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, and the University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland, and was approved by the ethics committees at both sites (approval number LNR/15/Austin/391 and KEK-ID2018-00746).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Shehabi reports receiving travel support and lecture fees, paid to Monash Health, and lecture fees from Pfizer (Malaysia) and Orion Pharma and fees for expert testimony from Stephens Lawyers and Consultants, Melbourne; Dr. Bellomo, receiving fees for expert testimony from Pfizer; and Dr. Takala, receiving consulting fees from Nestec. The Department of Intensive Care Medicine (Inselspital), Bern University Hospital has, or has had in the past, research contracts with Abionic SA, AVA AG, CSEM SA, Cube Dx GmbH, Cyto Sorbents Europe GmbH, Edwards Lifesciences LLC, GE Healthcare, ImaCor Inc., MedImmune LLC, Orion Corporation, Phagenesis Ltd. and research and development/consulting contracts with Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Nestec SA, Wyss Zurich. The money was paid into a departmental fund; the investigators received no personal financial gain.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cioccari, L., Luethi, N., Bailey, M. et al. The effect of dexmedetomidine on vasopressor requirements in patients with septic shock: a subgroup analysis of the Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation [SPICE III] Trial. Crit Care 24, 441 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03115-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03115-x