Abstract

Background

Rapid and accurate diagnosis of neonatal sepsis is highly warranted because of high associated morbidity and mortality. The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of a novel multiplex PCR assay for diagnosis of late-onset sepsis and to investigate the value of bacterial DNA load (BDL) determination as a measure of infection severity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in a neonatal intensive care unit. Preterm and/or very low birth weight infants suspected for late-onset sepsis were included. Upon suspicion of sepsis, a whole blood sample was drawn for multiplex PCR to detect the eight most common bacteria causing neonatal sepsis, as well as for blood culture. BDL was determined in episodes with a positive multiplex PCR.

Results

In total, 91 episodes of suspected sepsis were investigated, and PCR was positive in 53 (58%) and blood culture in 60 (66%) episodes, yielding no significant difference in detection rate (p = 0.17). Multiplex PCR showed a sensitivity of 77%, specificity of 81%, positive predictive value of 87%, and negative predictive value of 68% compared with blood culture. Episodes with discordant results of PCR and blood culture included mainly detection of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). C-reactive protein (CRP) level and immature to total neutrophil (I/T) ratio were lower in these episodes, indicating less severe disease or even contamination. Median BDL was high (4.1 log10 cfu Eq/ml) with a wide range, and was it higher in episodes with a positive blood culture than in those with a negative blood culture (4.5 versus 2.5 log10 cfu Eq/ml; p < 0.0001). For CoNS infection episodes BDL and CRP were positively associated (p = 0.004), and for Staphylococcus aureus infection episodes there was a positive association between BDL and I/T ratio (p = 0.049).

Conclusions

Multiplex PCR provides a powerful assay to enhance rapid identification of the causative pathogen in late-onset sepsis. BDL measurement may be a useful indicator of severity of infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Late-onset sepsis (LOS) is a serious nosocomial infection common among preterm and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants. Over 60% of VLBW infants are suspected of LOS at some point during hospitalization, and LOS is confirmed through blood culture in one-third of these infants [1]. Compared with infants without LOS, infants with LOS have a higher mortality rate, require longer hospitalization, and are at increased risk of impaired neurodevelopmental outcome [1,2,3]. Because most deaths occur in the first days following the onset of symptoms, accurate and rapid diagnosis followed by the initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy is of great importance.

Diagnosing LOS clinically can be challenging because signs and symptoms are generally nonspecific. Furthermore, blood culture, the diagnostic gold standard, often remains negative owing to the small blood volume that can be obtained from neonates and/or because of prior use of antibiotics [4, 5]. The clinical impact of the blood culture is also negatively affected by its turnaround time (TAT) because it usually requires 1 day of incubation. Several biomarkers have been identified as useful, rapid tools to aid in the diagnosis of LOS, but they fail to provide information on the causative pathogen [6, 7]. As a result, the development of a diagnostic test that detects pathogens that cause LOS in a rapid, sensitive, and specific manner is highly warranted to overcome the current limitations in diagnosing LOS.

Over the past decade, researchers in several studies have reported the use of real-time PCR for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis, and a recent meta-analysis indicates that PCR may be a valuable tool in the diagnostic arsenal [8,9,10,11,12]. For example, Jordan et al. have conducted several studies using broad-range 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR to rapidly diagnose sepsis in a low-risk neonatal population [11, 13, 14]. Researchers in another interesting study successfully used a gram-specific PCR to distinguish between gram-positive and gram-negative sepsis in order to anticipate the more severe course of gram-negative sepsis [12]. Although these PCR assay results are promising, widespread implementation in routine practice has not yet occurred, because these assays require additional steps to identify the pathogen to the species level, which is costly and labor-intensive and prolongs the TAT. Multiplex real-time PCR could overcome this issue, but it has been used in LOS only sporadically [15, 16]. We recently reported on a multiplex assay that rapidly identifies the most common pathogens that cause LOS using real-time PCR [17].

Another advantage of real-time PCR is that it allows quantitative measurements and thereby enables the determination of the bacterial DNA load (BDL) [18]. A growing body of evidence indicates a relationship between the BDL measured during infection and severity of disease [19,20,21,22,23,24]. For example, for meningococcal disease, Darton et al. demonstrated an association between a high BDL and an increased incidence of renal failure and death [20]. To our knowledge, the BDL has not been studied in a species-specific manner in infants with LOS. Besides providing potentially crucial information on the severity of disease in LOS, BDL may help to distinguish true infection from contamination in the specific case of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS).

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical utility of species-specific detection of bacterial DNA in whole blood samples for the diagnosis of LOS in preterm infants. Also, we evaluated the value of BDL in assessing the severity of infection.

Methods

Study population

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data collected in a prospective study that was conducted in the neonatal intensive care unit of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, between March 2009 and July 2013. Preterm (gestational age < 32 weeks) as well as VLBW (< 1500 g) infants suspected of having a nosocomial (age at onset > 72 h and hospitalized) bloodstream infection were eligible for the study. Patients with a (suspected) genetic or metabolic disorder were excluded from participation. The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the VU University Medical Center (reference 2008/77) approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all neonates prior to inclusion. The study protocol allowed the inclusion of multiple episodes of suspected nosocomial sepsis occurring in one infant.

Sample collection

Upon clinical suspicion of a bloodstream infection, before initiation of antibiotic treatment, a whole blood sample was collected aseptically through a newly inserted catheter for blood culture (BD BACTEC Peds Plus™/F Medium; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), PCR, and infection parameters. In a few episodes, an arterial (peripheral or umbilical) line was present and used for blood sampling. Blood samples for PCR were stored at −80 °C until further processing. Additional body samples for culture (e.g., urine, cerebrospinal fluid, tracheal aspirate, pustule) were obtained on indication of the physician. Blood cultures were incubated for 5 days (BD BACTEC 9240; BD Biosciences), and in case of a positive (blood) culture, microorganisms were identified using standard laboratory procedures, including matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry with the VITEK MS system (bioMérieux, Zaltbommel, The Netherlands). The length of time that the blood culture spent in the BACTEC incubator was recorded as the time to positivity.

DNA isolation and multiplex PCR assay

The design and validation of the multiplex real-time PCR assay, as well as the DNA isolation process, are described in detail elsewhere [17]. Briefly, DNA was isolated from 200 μl of whole blood with bacterial lysis buffer (Biocartis, Mechelen, Belgium) and the NucliSENS easyMag device (bioMérieux). Prior to DNA purification, samples were spiked with phocine herpesvirus 1 as extraction and amplification control (EAC). Positive and negative process controls were included.

The multiplex PCR assay, which consists of three reactions, allows the detection of the eight most common bacterial pathogens of LOS directly from blood in amounts as small as ten copies/PCR (Fig. 1) [17]. The PCRs were performed on a LightCycler 480 Instrument II (Roche Diagnostics, Almere, The Netherlands). If amplification was observed, the sample was subsequently tested in a monoplex reaction for BDL determination as described below.

Interpretation of PCR results and determination of BDL

PCR results were analyzed blinded for blood culture results. A sample was regarded as negative when it was noninhibited and all pathogen PCRs were negative. The sample was considered noninhibited when the quantification cycle (Cq) value of the EAC signal of the sample was within ± 2 SD of the EAC signal in the negative control samples.

Because the Staphylococcus spp. PCRs occasionally yielded low positive signals in negative control samples, a cutoff was set for the clinical samples: These were regarded as positive only in case of a Cq value ≤ 39 with fluorescence ≥ 50,000 arbitrary units and ≥ 2 Cq values lower than observed in the negative control sample. A sample was regarded to be positive for both CoNS and Staphylococcus aureus if the Cq value of the Staphylococcus spp. assay was 3 Cq values lower than the S. aureus-specific assay. In the S. aureus-specific assay, low amplification signals were confirmed with a second PCR assay.

The BDL was determined by including tenfold serial dilutions of cloned PCR amplicons to serve as a standard curve. The corresponding BDL expressed in log10 cfu Eq/ml was determined by correcting for blood volume and number of PCR target copies per genome.

Clinical data and definitions

Data were extracted from the patients’ medical records and included demographic, laboratory, and clinical data on the suspected infectious episode and outcome. The leukocyte count was further specified by calculating the immature to total neutrophil (I/T) ratio [25]. Episodes were included when clinical suspicion of LOS occurred in an infant who did not receive systemic antibiotics at least 24 h prior to onset of symptoms. Culture-proven sepsis was defined as an episode with at least one positive blood culture with a microorganism not considered as a contaminant (e.g., Bacillus spp.), and targeted antibiotic treatment continued for ≥ 7 days or until removal of incriminated vascular access. Clinical sepsis was defined as above but with negative blood culture(s). Localized infection was defined as an episode with clinical signs consistent with localized infection and a positive culture from a relevant body site or positive imaging in the absence of a positive blood culture and if targeted treatment continued for ≥ 7 days. No infection was defined as an episode with negative cultures and in which treatment was discontinued after 48–72 h. A polymicrobial infection episode was defined as an episode in which more than one microorganism was detected by either multiplex PCR or blood culture.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated with standard two-by-two tables and blood culture as the gold standard. The difference in positivity rate between blood culture and PCR was explored with the McNemar test. Comparison of groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to investigate the relationship between continuous variables. Subsequently, linear (hierarchical) regression analysis was performed if applicable.

Results

Study population

In total, 91 episodes of suspected LOS occurring in 77 neonates were included, of which 13 infants contributed 2 episodes and 1 infant 3 episodes of suspected LOS (Table 1). Culture-proven sepsis was diagnosed in 57 episodes (63%), clinical sepsis in 4 (4%), and localized infection in 9 (10%), whereas no infection was diagnosed in 21 episodes (23%). Localized infection included five episodes of necrotizing enterocolitis, three episodes of pneumonia, and one episode of urinary tract infection.

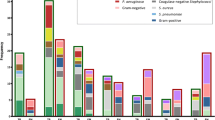

Evaluation of multiplex PCR for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis

Multiplex PCR was positive in 53 episodes (58%) and blood culture in 60 (66%). Blood culture and PCR were concordant positive in 41 episodes, concordant negative in 25, and discordant in 25. Six discordant episodes were detected by PCR only, 12 by blood culture only, and 7 were polymicrobial (Table 2; Additional file 1). There was no significant difference in positivity rates between both assays (p = 0.17). CoNS were the most frequently detected microorganisms, followed by S. aureus (Table 2). Streptococcus agalactiae was detected in three episodes (two episodes detected only by PCR). Gram-negative sepsis was rare (n = 4), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens were not detected by any method.

For infection episodes (n = 84, excluding polymicrobial infections) the multiplex PCR demonstrated a sensitivity of 77% (95% CI 64–88), specificity of 81% (95% CI 63–93), positive predictive value of 87% (95% CI 74–95), and negative predictive value of 68% (95% CI 50–82) compared with blood culture. In this study, seven episodes were polymicrobial, of which three were detected by PCR only and two by blood culture only (see Additional file 1). All episodes with polymicrobial infections showed discordant results between blood culture and PCR, indicating the difficulty of diagnosing polymicrobial infections. For example, for one infant with necrotizing enterocolitis, blood culture grew lactobacilli, whereas PCR detected S. agalactiae, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella spp., and CoNS.

Evaluation of patients with discordant results between blood culture and PCR

The results of PCR were negative for 11 episodes with CoNS-positive blood culture and 1 with S. aureus (Table 2). Ten of these episodes were considered culture-proven sepsis, whereas in two episodes, blood culture was regarded to be contaminated (Table 3). Therefore, the PCR results were presumably false-negative in ten episodes and true-negative in two episodes (for details, see Table 3, patients 5 and 12).

Interestingly, multiplex PCR was positive in six episodes associated with a negative blood culture (one S. aureus, one S. agalactiae, and four CoNS). In two of these episodes, septicemia was very likely based on clinical data and other cultures (Table 3, patients 13 and 16). In one episode, the PCR result was possibly clinically relevant (patient 17), and in three episodes, its clinical relevance was uncertain.

In episodes with discordant results between blood culture and PCR (n = 18), C-reactive protein (CRP) was significantly lower than in episodes with both a positive PCR and blood culture (3 mg/L versus 16 mg/L; p = 0.013). The absolute leukocyte count was not different (p = 0.99) between these groups, but the I/T ratio was lower in episodes with discordant results than in episodes with concordant positive results (0.07 versus 0.18; p = 0.001).

BDL at onset of neonatal sepsis

The BDL was determined for all (n = 53) PCR-positive infection episodes, including six polymicrobial infections. Load determination failed in two samples. BDL ranged from 55 to 22,976,150 cfu Eq/ml (median 13.514 cfu Eq/ml; 25–75% interquartile range 2420–63,745 cfu Eq/ml), or from 1.74 to 7.36 log10 cfu Eq/ml (median 4.13 log10 cfu Eq/ml) (Fig. 2). The BDL was significantly higher in blood culture-positive samples, with a median BDL of 4.5 versus 2.5 log10 cfu Eq/ml (p < 0.0001). Likewise, BDL and blood culture time to positivity showed a significant association when we took into account the time that had transpired between blood culture collection and incubation at the laboratory (R-square change 0.22; p = 0.001).

Distribution of the bacterial DNA load at onset of sepsis, stratified by pathogen. Monomicrobial (circles) and polymicrobial (triangles) infection episodes and blood culture results (open symbols = positive, closed symbols = negative) are presented as indicated. The dashed line indicates the lower detection limit

BDL was evaluated as a marker of severity of infection by investigating the correlation with established markers of infection. For CoNS infection episodes (n = 35), BDL showed a positive correlation with CRP (r s = 0.48; p = 0.004), but not with I/T ratio, total leukocyte count, or thrombocytopenia. Subsequent linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant association between BDL and CRP (R-square 0.125; p = 0.04).

For S. aureus infection episodes (n = 11), no significant association was found for CRP, total leukocyte count, or thrombocytopenia with BDL. However, for the I/T ratio, there was a trend toward a strong correlation (r s = 0.6; p = 0.09) with a positive association (adjusted R-square 0.37; p = 0.049). Severe complications such as mortality and shock requiring inotropy were too rare to be evaluated.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated a newly developed multiplex PCR for diagnosis of LOS directly in blood in a group of preterm neonates, and we explored the additional value of BDL measurement. There was no significant difference in detection rates of multiplex PCR compared with blood culture. Multiplex PCR showed a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 81%. Both PCR and blood culture provided additional microbiological identification and thus were complementary. These findings are in line with previous reports that demonstrate the use of PCR as a rapid tool to enhance diagnosis of neonatal sepsis [8]. This study adds to the growing body of evidence that direct species identification with PCR, with results potentially available within 4 h of blood sampling as compared with 14 h of incubation, enables early initiation of targeted therapy. Twenty-five of 91 infection episodes yielded discordant results between blood culture and PCR and were mainly detections of CoNS. Interestingly, both CRP and I/T ratio were significantly lower in discordant episodes, suggesting that these neonates had less severe disease or that the detected pathogen represented contamination. The fact that two episodes with CoNS-positive blood culture and CoNS-negative PCR were regarded as noninfectious further illustrates this point. Another important explanation may be suboptimal sensitivity of PCR. Each PCR contained an equivalent of only 18 μl of blood (derived from 200 μl of blood, approximately 10% of which is used for PCR) compared with 500 μl input in blood culture. Increasing input blood volume is therefore likely to improve sensitivity. Currently, several assays are in development that allow larger input blood volumes [26, 27]. Another advantage of PCR is that it is presumably less influenced by antibiotic treatment, as reported in the literature [28].

All polymicrobial infection episodes showed discordant results between blood culture and PCR. This finding demonstrates the difficulty when diagnosing polymicrobial sepsis, such as the fact that blood culture regularly detects only the most rapidly growing microorganism. In two episodes where PCR detected both S. aureus and CoNS, blood culture detected only CoNS. The BDL of CoNS was > 25 times higher than that of S. aureus.

It is generally appreciated that blood culture serves as an imperfect reference test with both suboptimal sensitivity and specificity [29,30,31]. Use of a Bayesian model, which allows for evaluation of a new diagnostic test in cases of an imperfect reference test, is not possible for lack of additional reliable infection markers for this neonatal patient population [32,33,34].

Instead, we assessed the validity of individual discrepant blood culture PCR results (Table 3). This indicated that 2 of 11 positive blood cultures were likely false-positive results and 3 of 6 PCR results were likely true-positive results, which would increase the diagnostic utility of PCR. For two CoNS PCR-positive episodes, subsequently obtained blood samples were also positive in PCR, substantiating the true-positive result. Our quantitative measurements, the first to be reported for LOS in preterm infants, revealed often high BDL similar to measurements during meningococcal and pneumococcal disease in children [20, 21].

The magnitude of bacteremia, as assessed with quantitative culturing, is generally low but inversely related to age and highest in neonates [35]. This is in line with our results because we found high BDL that was associated with short blood culture time to positivity. The association was not as strong as one would expect, which may be partly explained by the detection of nonviable bacteria and free bacterial DNA by PCR. Furthermore, BDL correlated significantly with blood culture positivity, indicating its potential to measure the level of bacteremia.

In CoNS infection episodes, BDL was associated with CRP, indicating the potential use of BDL as a marker of severity of infection. For S. aureus sepsis, BDL was associated with the I/T ratio, even though only 11 episodes could be evaluated. We observed, for example, that the only infant who died of S. aureus sepsis had the highest BDL. These findings suggest that the course of BDL might be a useful indicator of treatment success.

This study has several limitations. First, the limited number of included infants prohibited thorough evaluation of the diagnostic performance in gram-negative sepsis and of the BDL for less prevalent pathogens. Because we recruited infants over a 4-year period, we believe we made all efforts to include a sufficient number of episodes of suspected LOS in this single-center evaluation. Second, because this assay detects DNA, it does not discriminate between viable and nonviable organisms or free and cell-associated DNA, which may have impacted the comparison of BDL with blood culture. Blood was stored at −80 °C until further processing, which could have affected the integrity of the DNA.

This is a proof-of-concept study showing that rapid bacterial species identification directly in blood is feasible in preterm neonates. Our assay could be a valuable add-on test but lacks sufficient negative predictive value to exclude sepsis. Moreover, because we performed our study in a high-risk population for which sepsis was diagnosed in 67% of episodes, it is unlikely that one test alone could exclude sepsis. Even in low-risk populations, PCR results were shown not to be sufficient to rule out sepsis [36].

The rise of antibiotic resistance and growing evidence of the adverse effects of antibiotics on gut microbiome composition, especially for neonates, further emphasizes the need for early targeted treatment [37]. Even more important, rapid diagnosis in combination with an antimicrobial stewardship program improves outcome of sepsis in the adult population [38, 39]. It is likely that this is also true for VLBW neonates, because neonatal sepsis is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1, 40, 41].

Considering the value of multiplex PCR for diagnosis of LOS, future studies should be done to evaluate the clinical impact of this assay using an algorithmic approach that includes BDL and other infection parameters rather than PCR results only. This should be performed in a large multicenter study to ensure sufficient coverage of both gram-positive and gram-negative sepsis episodes. The ultimate aim would be to optimize antibiotic treatment by early targeted treatment and estimation of infection severity, as well as restriction of antibiotic use because unnecessary antibiotic therapy is associated with adverse outcomes [42].

Conclusions

This study shows that multiplex PCR has fair diagnostic utility compared with blood culture, with the advantage of rapid test results. PCR provides a useful add-on test for diagnosis of LOS in preterm infants. Additional BDL determination provides a measure of infection severity that deserves to be further evaluated.

Abbreviations

- BDL:

-

Bacterial DNA load

- CoNS:

-

Coagulase-negative staphylococci

- Cq :

-

quantification cycle

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EAC:

-

Extraction and amplification control

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- I/T ratio:

-

Immature to total neutrophil ratio

- LOS:

-

Late-onset sepsis

- TAT:

-

Turnaround time

- TTP:

-

Time to positivity

- VLBW:

-

Very low birth weight

References

Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):285–91.

Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004;292:2357–65.

Pessoa-Silva CL, Miyasaki CH, de Almeida MF, Kopelman BI, Raggio RL, Wey SB. Neonatal late-onset bloodstream infection: attributable mortality, excess of length of stay and risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:715–20.

Chiesa C, Panero A, Osborn JF, Simonetti AF, Pacifico L. Diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: a clinical and laboratory challenge. Clin Chem. 2004;50:279–87.

Connell TG, Rele M, Cowley D, Buttery JP, Curtis N. How reliable is a negative blood culture result? Volume of blood submitted for culture in routine practice in a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2007;119:891–6.

van Rossum AM, Wulkan RW, Oudesluys-Murphy AM. Procalcitonin as an early marker of infection in neonates and children. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:620–30.

Srinivasan L, Harris MC. New technologies for the rapid diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:165–71.

Pammi M, Flores A, Leeflang M, Versalovic J. Molecular assays in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e973–85.

McCabe KM, Khan G, Zhang YH, Mason EO, McCabe ER. Amplification of bacterial DNA using highly conserved sequences: automated analysis and potential for molecular triage of sepsis. Pediatrics. 1995;95:165–9.

Wu YD, Chen LH, Wu XJ, Shang SQ, Lou JT, Du LZ, et al. Gram stain-specific-probe-based real-time PCR for diagnosis and discrimination of bacterial neonatal sepsis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2613–9.

Jordan JA, Durso MB. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for detecting bacterial DNA directly from blood of neonates being evaluated for sepsis. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:575–81.

Chan KYY, Lam HS, Cheung HM, Chan AKC, Li K, Fok TF, et al. Rapid identification and differentiation of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial bloodstream infections by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in preterm infants. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2441–7.

Jordan JA, Durso MB, Butchko AR, Jones JG, Brozanski BS. Evaluating the near-term infant for early onset sepsis: progress and challenges to consider with 16S rDNA polymerase chain reaction testing. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:357–63.

Jordan JA, Durso MB. Comparison of 16S rRNA gene PCR and BACTEC 9240 for detection of neonatal bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2574–8.

Kasper DC, Altiok I, Mechtler TP, Böhm J, Straub J, Langgartner M, et al. Molecular detection of late-onset neonatal sepsis in premature infants using small blood volumes: proof-of-concept. Neonatology. 2013;103:268–73.

Tröger B, Härtel C, Buer J, Dördelmann M, Felderhoff-Müser U, Höhn T, et al. Clinical relevance of pathogens detected by multiplex PCR in blood of very-low-birth weight infants with suspected sepsis – multicentre study of the German Neonatal Network. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159821.

van den Brand M, Peters RPH, Catsburg A, Rubenjan A, Broeke FJ, van den Dungen FAM, et al. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR assay for the rapid diagnosis of neonatal late onset sepsis. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;106:8–15.

Peters RP, van Agtmael MA, Danner SA, Savelkoul PH, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. New developments in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:751–60.

Rello J, Lisboa T, Lujan M, Gallego M, Kee C, Kay I, et al. Severity of pneumococcal pneumonia associated with genomic bacterial load. Chest. 2009;136:832–40.

Darton T, Guiver M, Naylor S, Jack DL, Kaczmarski EB, Borrow R, et al. Severity of meningococcal disease associated with genomic bacterial load. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:587–94.

Carrol ED, Guiver M, Nkhoma S, Mankhambo LA, Marsh J, Balmer P, et al. High pneumococcal DNA loads are associated with mortality in Malawian children with invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:416–22.

Hackett SJ, Guiver M, Marsh J, Sills JA, Thomson AP, Kaczmarski EB, et al. Meningococcal bacterial DNA load at presentation correlates with disease severity. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:44–6.

Lisboa T, Waterer G, Rello J. We should be measuring genomic bacterial load and virulence factors. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10 Suppl):S656–62.

Peters RP, de Boer RF, Schuurman T, Gierveld S, Kooistra-Smid M, van Agtmael MA, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA load in blood as a marker of infection in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3308–12.

Manroe BL, Weinberg AG, Rosenfeld CR, Browne R. The neonatal blood count in health and disease. I. Reference values for neutrophilic cells. J Pediatr. 1979;95:89–98.

Vincent JL, Brealey D, Libert N, Abidi NE, O’Dwyer M, Zacharowski K, et al. Rapid diagnosis of infection in the critically ill, a multicenter study of molecular detection in bloodstream infections, pneumonia, and sterile site infections. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2283–91.

Loonen AJM, Bos MP, van Meerbergen B, Neerken S, Catsburg A, Dobbelaer I, et al. Comparison of pathogen DNA isolation methods from large volumes of whole blood to improve molecular diagnosis of bloodstream infections. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72349.

Gies F, Tschiedel E, Felderhoff-Müser U, Rath PM, Steinmann J, Dohna-Schwake C. Prospective evaluation of SeptiFast multiplex PCR in children with systemic inflammatory response syndrome under antibiotic treatment. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:378.

Schelonka RL, Chai MK, Yoder BA, Hensley D, Brockett RM, Ascher DP. Volume of blood required to detect common neonatal pathogens. J Pediatr. 1996;129:275–8.

Kellogg JA, Manzella JP, Bankert DA. Frequency of low-level bacteremia in children from birth to fifteen years of age. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2181–5.

Healy CM, Baker CJ, Palazzi DL, Campbell JR, Edwards MS. Distinguishing true coagulase-negative Staphylococcus infections from contaminants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2013;33:52–8.

Shane AL, Stoll BJ. Recent developments and current issues in the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of bacterial and fungal neonatal sepsis. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:131–41.

Limmathurotsakul D, Turner EL, Wuthiekanun V, Thaipadungpanit J, Suputtamongkol Y, Chierakul W, et al. Fool’s gold: why imperfect reference tests are undermining the evaluation of novel diagnostics: a reevaluation of 5 diagnostic tests for leptospirosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:322–31.

Hunink MGM, Glasziou PP, Siegel JE, Weeks JC, Pliskin JS, Elstein AS, Weinstein MC. Decision making in health and medicine: integrating evidence and values. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Yagupsky P, Nolte FS. Quantitative aspects of septicemia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:269–79.

Jordana-Lluch E, Giménez M, Quesada MD, Ausina V, Martró E. Improving the diagnosis of bloodstream infections: PCR coupled with mass spectrometry. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:501214.

Gibson MK, Crofts TS, Dantas G. Antibiotics and the developing infant gut microbiota and resistome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;27:51–6.

Timbrook TT, Morton JB, McConeghy KW, Caffrey AR, Mylonakis E, LaPlante KL. The effect of molecular rapid diagnostic testing on clinical outcomes in bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:15–23.

Buehler SS, Madison B, Snyder SR, Derzon JH, Cornish NE, Saubolle MA, et al. Effectiveness of practices to increase timeliness of providing targeted therapy for inpatients with bloodstream infections: a laboratory medicine best practices systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:59–103.

Alshaikh B, Yusuf K, Sauve R. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2013;33:558–64.

Stoll BJ, Fanaroff A. Early-onset coagulase-negative staphylococcal sepsis in preterm neonate. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network. Lancet. 1995;345:1236–7.

Ting JY, Synnes A, Roberts A, Deshpandey A, Dow K, Yoon EW, et al. Association between antibiotic use and neonatal mortality and morbidities in very low-birth-weight infants without culture-proven sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:1181–7.

Bizzarro MJ, Ehrenkranz RA, Gallagher PG. Concurrent bloodstream infections in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 2014;164:61–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Part of this research was funded by ZonMw (project number 205 100 007) and Fonds Nuts Ohra. Biocartis kindly provided the BLB and NB2 reagents. The sponsors were not involved in the design and execution of the study.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file. The remaining datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FAMvdD, MMvW, AMvF, RPHP, and PHMS were involved in the conception and design of the study. FAMvdD, MvdB, MMvW, and AdL made substantial contributions to the acquisition of the clinical data. MvdB, MPB, and AR performed the PCRs and BDL measurements. MvdB, FAMvdD, MPB, and RPHP analyzed the data. MvdB, FAMvdD, MPB, MMvW, AMvF, RPHP, and PHMS interpreted the data. MvdB drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the VU University Medical Center (reference 2008/77) approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all neonates prior to inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MPB is an employee of Microbiome Ltd. PHMS is one of the founders and a shareholder of the VUmc spinoff company Microbiome Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Detection of pathogens in blood by blood culture and PCR for polymicrobial infection episodes. (DOC 51 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Brand, M., van den Dungen, F.A.M., Bos, M.P. et al. Evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of bacterial DNA directly in blood of preterm neonates with suspected late-onset sepsis. Crit Care 22, 105 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2010-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2010-4