Abstract

Background

Rapid development and global spread of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumoniae) as a major cause of nosocomial infections is really remarkable. The aim of this study was to explore risk factors for health care associated blood stream infections (BSI) caused by ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in children and analyze clinical outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients younger than 18 years-old with blood stream infection caused by K. pneumoniae was performed. Patients with ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were compared with ESBL-non-producing isolates in terms of risk factors, outcome and mortality.

Results

Among 111 K. pneumoniae isolates 62% (n = 69) were ESBL –producing K. pneumoniae. The median total length of hospitalization and median length of stay in hospital before infection was significantly higher in patients with ESBL-producing isolates than ESBL-non-producing. Use of combined antimicrobial treatment was significantly different between ESBL-producing and ESBL-non-producing groups, 75.4% and 24.6%, respectively (p = 0.001). Previous aminoglycoside use was higher in cases with ESBL –producing isolates (p = 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed a significant correlation between mortality and use of combined antibiotics (OR 4.22; p = 0.01).

Conclusion

ESBL production in K. pneumoniae isolates has a significant impact on clinical course of BSIs. Total length of hospitalization, length of hospital stay before infection, prior combined antibiotic use and use of aminoglycosides were significant risk factors for development of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae related BSI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Significant number of health care associated infections in adults and children are caused by gram-negative microorganisms [1, 2]. During the last ten years, changes in antibiotic susceptibility profiles of gram-negative microorganisms have been studied because there is an increasing prevalence of infections due to ESBL (Extended spectrum β lactamase) producing Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumoniae). K. pneumoniae is an important opportunistic pathogen of children, causing a wide variety of infections including blood stream infections (BSI); approximately 75% of patients of BSIs are healthcare- associated [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. According to data from National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System in United States in 2003, K. pneumoniae accounted for 18% of the gram-negative bacteremia and 4.2% of all bacteremia [12]. Since the treatment strategies of these infections are limited [3], children with these infections tended to experience high rates of mortality and longer lengths of hospitalization after infection compared to children with BSI due to non-ESBL-producing isolates [13]. Although risk factors for bacteremia with ESBL-producer gram-negative bacilli have been studied in many studies for adults, it is still a serious concern for children on account of few pediatric studies. The objectives of this study were to assess risk factors for health care associated BSI caused by ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in children, analyze clinical outcomes and compare with ESBL-non-producers.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was performed in Hacettepe University Ihsan Dogramaci Children’s Hospital in Turkey.

Patient selection

Patients younger than 18 years-old with positive blood cultures for K. pneumoniae from January 2011 to December 2015, were involved in the study. Health –care associated blood stream infection was defined as positive blood culture, obtained from a peripheral vein or central catheter, that is collected at least 48 h after hospital admission and within 48 h if the patient was hospitalized within the previous 60 days. Clinical findings of bacteremia were accepted as presence of at least one of fever, chills or hypotension [14].

Study protocol

Information regarding clinical and demographic characteristics; underlying medical conditions; total length of hospitalization (LOH); length of stay in hospital before infection; duration of treatment for infection; immunosuppression due to chemotherapy induced neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <500 cells/mm3); previous surgical procedure during hospital stay; mechanical ventilation; polymicrobial bacteremia; presence of central venous catheter; prior colonization of urinary tract and/or lower airway and/or catheter colonization with K. pneumoniae before identification of BSI; antimicrobial exposure (only the ones for at least 48 h during the previous 14 days were studied): broad spectrum cephalosporins, and β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, glycopeptides (vancomycin or teicoplanin), and exposure to combined antibiotics studied. Extended spectrum beta lactamase production was defined as presence of beta-lactamases that hydrolyse penicilins, 1-3rd generation cephalosporins, but do not hydrolyse cefoxitin or carbapenems and are generally inhibited by beta-lactamase inhibitors [15]. Outcome was evaluated as follows 1) Response at day 6 with occurrence of one of the followings: resolution of fever and other local or systemic signs of infection, normal white blood cell count, and negative blood culture. 2) Relapse: recurrence of infection with a positive blood culture within a month after discontinuation of therapy. 3) Mortality was analyzed as 30-day and 60-day mortality [16]. Number of isolates were also evaluated by years in order to investigate variations in time.

Microbiological analysis

For identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the isolates BD Phoenix (BD Diagnostics System, Sparks, MD) automated system used between January 2010 and June 2013. After June 2013, identification of K. pneumoniae isolates was done by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by using VITEK 2 compact (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) system. The results of antimicrobial susceptibility tests were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations [17].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) Descriptive analyses were performed including medians, interquartile ranges, standard deviations for continuous variables and frequency distributions for categorical variables. P values were calculated using the Chi -Square or Fisher exact tests to compare categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables (p value ≤0.05). Variables with p values <0.20 in univariate analysis were put into multivariate analysis in order to identify independent risk factors. To determine adjust effect of risk factors on mortality logistic regression was used (p value ≤0.10 was considered significant). For analysis of factors that lengthen total stay time in hospital linear regression model was performed with a significant p value ≤0.05.

Results

A total of 97 pediatric patients with 111 K. pneumoniae isolates were included in the study. Median age of patients was 8.0 months (IQR: 2–45.6). Sixty-nine isolates (62%) were ESBL- producer and 42 (37.8%) were ESBL-non-producer. Twenty-eight (25.2%) of the isolates presented carbapenem-resistance. Most of the patients in ESBL-producing group were males (63.8%). No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in terms of gender (p = 0.99), and patients with ESBL-producing isolates were younger than ESBL-non-producers (p = 0.04). Patients younger than 12 months of age constituted 57.7% (n = 56) of overall group. Underlying medical conditions/diseases were not significantly different between two groups. ESBL- producing group displayed 7 (11.4%) hematologic malignancy, 6 (9.8%) oncologic malignancy, 8 (13.1%) congenital heart diseases, 2 (3.2%) primary immunodeficiencies, 10 (16.3%) neurologic/metabolic diseases, 9 (14.7%) gastrointestinal diseases, 6 (9.8%) premature birth (Table 1).

The median total length of hospitalization was significantly different between ESBL-producers (56, IQR:32–89 days) and ESBL-non-producers (34, IQR: 21–71 days) (p = 0.03). The median length of stay in hospital before infection was significantly longer for ESBL- producing group than that of ESBL-non-producing group (p = 0.001). Duration of treatment for infection displayed no significant difference (Table 1). Of all, 12.6% (n = 14) of isolates were polymicrobial. The microorganisms identified in addition to K. pneumoniae were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 5), Enterobacter cloacae (n = 3), Enterococcus faecium (n = 2), Enterococcus faecalis (n = 1), Candida tropicalis (n = 1), Candida parapsilosis (n = 1), Acinetobacter baumanii (n = 1).

Univariate analysis of predisposing factors such as presence of central venous catheter, prior surgery, polymicrobial bacteremia, presence of chemotherapy associated neutropenia and prior K. pneumoniae colonization depicted no statistically significant difference whereas presence mechanical ventilation was different between ESBL-producer (81.6%) and ESBL-non-producer (18.4%) groups (p = 0.005).

We performed analysis on relationship of previous antibiotic usage before identification of BSI. Use of combined antimicrobial treatment was significantly different between ESBL-producing and ESBL-non-producing groups, 75.4% and 24.6%, respectively (p = 0.001). When analysis of antibiotic regimens was considered, previous aminoglycoside use was higher in patients with ESBL-producing isolates than the ones with ESBL-non-producing isolates (p = 0.001) (Table 1).

Although mortality, treatment response at day 6 and relapse rates were not significantly different between comparison groups, ratios of crude mortality, 30-day and 60-day mortality were relatively higher for patients with ESBL producing isolates (respectively, 29%, 24.6%, 17.5%, p > 0.05). Logistic regression analysis showed a significant correlation between mortality and two variables: mechanical ventilation (OR 2.4; CI 0.933–6.211; p = 0.06) (CI: Confidence interval) and use of combined antibiotics (OR 4.22; CI 1.293–13.791; p = 0.01). In addition to this, linear regression displayed a significant correlation between total length of hospital stay and three variables: polymicrobial bacteremia (OR 117.148; CI 73.634–160.663; p = 0.0), prior glycoprotein use (OR 41.96; CI 12.697–71.223; p = 0.05), presence of central venous catheter (OR 32.970; CI 3.871–62.069; p = 0.02) (Table 2).

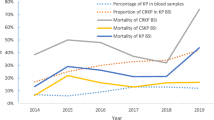

When the distribution of isolates was assessed by year, there was no significant difference between years in univariate analysis in terms of percentage of ESBL-producing isolates. ESBL-producing strains were relatively high in 2014 (n = 28, 82.4%) compared to previous 3 years, going forward with a decline in 2015 (n = 15, 57.7%) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Here, we report clinical significance and outcomes of pediatric health care associated BSIs caused by ESBL-producing and ESBL-non-producing K. pneumoniae, over the 5 years study period. In the present study, in 5 years period we observed 62% ESBL production in K. pneumoniae, causing BSI. Blood stream infections are one of the most important complications of health care settings. In a multi-centered study of nosocomial infections in pediatric patients, 36% had bacteremia and 37% of patients constituted gram-negative bacilli [2]. Extremely resistant strains are coming into view in several gram-negative microorganisms with resistance to all commonly used antimicrobials [18]. In early reports along Europe, 37.5% of K. pneumoniae were ESBL-producer [2]. Felder K et al. reported that ESBL-producing strains ranged from 20.3% to 22.5% [19]. Many other regions worldwide stated a prevalence of ESBL in Enterobacteriacea spp. approximately 10–35% [20]. Statistics vary widely from continent to continent and from center to center, with prevalence up to 70% [21]. Our higher result compared to literature may possibly be attributed to our patient spectrum, consisting of many clinically high risky groups including hematology- oncology malignancies, patients in intensive care units and neonates. These groups need a variety of interventions, accompanying long lasting and combined therapies during their hospital stay. Furthermore, analysis of distribution of isolates by years revealed a peak in 2014. We have been strictly following the deviations of these infections in our hospital. According to our remarkable numbers, we introduced some regulatory preventive strategies. The precautions include isolation of the patients with antibiotic resistant microorganisms, follow-up of isolated patients, effective study of committee of hand hygiene including vigorous education of personnel, control of inappropriate broad spectrum antibiotic use, especially including carbapenems.

Levy et al. reported that gram-negative organisms encounter for more than 50% of all bacteremia in children while K. pneumoniae accounts for the most commonly identified pathogen, comprising 26% of isolates [6]. In early studies among pediatric BSIs caused by K. pneumoniae, 67% were younger than 12 months of age and 93% of the patients had an underlying condition predisposing to opportunistic infections [22].

In the SENTRY report in 2004, ESBL production was reported to be 41.7% in children younger than 1 year of age and 22.5% between 1 and 12 years of age [23]. Other studies revealed a 2-fold decrease in prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae (Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp.) after the age of 1 year [19]. Supporting these data, in the present study, patients younger than 12 months of age constituted 57.7% of overall group and younger patients were significantly under greater risk for BSI with ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae.

In the current study, clinical responses were similar for patients with ESBL- producing and non-producing K. pneumoniae. Although analysis did not revealed statistical significance, crude mortality, 30-day and 60-day mortality were relatively higher in patients with ESBL-producing isolates. Infection related mortality of the group in the present study (24.6%) was similar to the cohort study of Kim et al. in which 26.7% of children with BSI caused by ESBL (+) bacteria died as compared with 5.7% mortality in patients with non-producers with statistical significance [24]. The results are varying among the centers. In a report from Tanzanian children with septicemia, fatality rate was 71% with ESBL (+) gram-negative bacteria [25].

Many adult studies identified many risk factors for ESBL (+) K. pneumoniae infections. Prolonged hospital stay, prolonged stay in intensive care unit, recent exposure to multiple antibiotics and indwelling invasive devices were determined as risk factors for acquisition of ESBL (+) K. pneumoniae in adult populations [24, 26,27,28]. In one of the pediatric studies Kim et al. identified prior hospitalization, prior intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, presence of central venous catheter, development of breakthrough bacteremia during antibiotic therapy, and exposure to extended-spectrum cephalosporins within 30 days of infection as risk factors for blood stream infections caused by ESBL (+) K. pneumoniae in neonates with bacteremia [24]. Benner et al. studied the outcome of patients with ESBL producing bacterial infections in pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) [29] and they found that patients with infections due to ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae had a longer duration of hospital stay as well as PICU stay, while length of stay in the PICU achieved statistical significance. Analysis of total length of hospitalization revealed a significant difference between ESBL producer and non-producer K. pneumoniae isolates in the present study. Further analysis showed that risk factors prolonging total length of hospitalization were presence of accompanying microorganisms to the infection, prior glycopeptide use within last 14 days before infection and presence of central venous catheter during infection. Additively, length of hospital stay before infection was significantly longer for ESBL producers, potentiating the risk of hospital acquisition. A previous pediatric study, similarly, identified the significant association between ESBL (+) K. pneumoniae BSIs and longer length of hospital stay before infection [30]. Substantiating these findings, a recent adult study showed significant difference between ESBL-producer and non-producer Enterobacteriacea, concerning duration of time from hospital admission to positive blood culture [31].

We found significant association between ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae bacteremia and use of combined antibiotics in the study. Among the antibiotics previous aminoglycoside use significantly increased risk of blood stream infection. Until now, for children, there are some studies supporting association of previous antibiotic use and ESBL producing Enterobacteriacea, many focusing on urinary tract infections and prophylaxis [32,33,34,35]. Recently, Zerr et al. delineated a relative risk of having ESBL producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae than non-producing isolate 2.2 times higher among antibiotic users in last 30 days of infection. In addition, they stated that subgroup analysis resulted in a significant relation between Amp-C producing Enterobacteriacea isolates and third generation cephalosporin use [36]. All of these findings exhibit the close relationship between prior antibiotic exposure and subsequent infections with resistant K. pneumoniae.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, due to the retrospective design, data was obtained from clinical reports, so some incomplete data was unavoidable and some characteristics showed no or limited statistical significance. Secondly, the data lacks genotyping and molecular analysis, which if shown, would be very valuable demonstrating our regional pediatric profile.

Conclusion

As shown in many adult studies, ESBL producing K. pneumoniae is one of the major causes of health care associated BSI infections in pediatric patients. We found that total length of hospitalization, length of hospital stay before infection, being younger than 12 months of age, and prior antibiotic use especially aminoglycosides were strongly affecting development of BSI with resistant K. pneumoniae. Use of combined antibiotics and mechanical ventilation before infection were increasing risk of mortality due to ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae related BSI. It is obvious that some of these factors can be preventable. These results suggest that proper antimicrobial agent selection, appropriate durations of treatment and less invasive procedures may reduce incidence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in children.

Abbreviations

- BSI:

-

Blood stream infections

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory standards Institute

- ESBL:

-

Extended spectrum β lactamase

- K. pneumoniae :

-

Klebsiella pneumonia

- LOH:

-

Total length of hospitalization

- MALDI-TOF MS:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry

References

Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, et al. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta- lactamase production in nosocomial Infections. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:26–32.

Raymond J, Aujard Y. Nosocomial infections in pediatric patients: a European, multicenter prospective study. European Study Group. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:260–3.

Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:159–66.

Vermaat JH, Rosebrugh E, Ford-Jones EL, Ciano J, Kobayashi J, Miller G. An epidemiologic study of nosocomial infections in a pediatric long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control. 1993;21:183–8.

Krontal S, Leibovitz E, Greenwald-Maimon M, Fraser D, Dagan R. Klebsiella bacteremia in children in southern Israel (1988–1997). Infection. 2002;30:125–31.

Levy I, Leibovici L, Drucker M, Samra Z, Konisberger H, et al. A prospective study of gram-negative bacteremia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:117–22.

Lin RD, Hsueh PR, Chang SC, Chen YC, Hsieh WC, Luh KT. Bacteremia due to Klebsiella oxytoca: clinical features of patients and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1217–22.

Davies HD, Jones EL, Sheng RY, Leslie B, Matlow AG, Gold R. Nosocomial urinary tract infections at a pediatric hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:349–54.

Cheng CH, Tsai MH, Su LH, Wang CR, Lo WC, Tsau YK, et al. Renal abscess in children: a 10-year clinical and radiologic experience in a tertiary medical center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:1025–7.

Newman N, Wattad E, Greenberg D, Peled N, Cohen Z, Leibovitz E. Community- acquired complicated intra-abdominal infections in children hospitalized during 1995–2004 at a pediatric surgery department. Scand J Infect Dis 2009;41:720–6.

Ozgen U, Uzum I, Mizrak B, Saraç K. Typhilitis in rectum. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:e32–3.

Gaynes R, Edwards JR. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:848–54.

Barson WJ, Marcon MJ. Klebsiella and Raoutella Species. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 4th ed., Elsevier: Churchill Livingstone; 2012. p. 799–803.

Gulen TA, Guner R, Celikbilek N, Keske S, Tasyaran M. Clinical importance and cost of bacteremia caused by nosocomial multi drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;38:32–5.

Moxon CA, Paulus S. Beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae infections in children. J Inf Secur. 2016;5(72 Suppl):S41–9.

Marquet K, Liesenborgs A, Bergs J, Vleugels A, Claes N. Incidence and outcome of inappropriate in-hospital empiric antibiotics for severe infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:63.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-fourth Informational Supplement M100-S24. Wayne: CLSI; 2014.

Nordmann P. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: overview of a major public health challenge. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:51–6.

Felder K, Biedenbach D, Jones RN. Assessment of pathogen frequency and resistance patterns among pediatric patient isolates: report from the 2004 SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program on 3 continents. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56:427–36.

Rodriquez-Bano J, Pascual A. Clinical significance of extended-spectrum B- lactamases. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2008;6:671–83.

Superti SV, Augusti G, Zavascki AP. Risk factors for and mortality of extended- spectrum-β- lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli nosocomial bloodstream infections. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:211–6.

Bonadio WA. Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in children. Fifty-seven cases in 10 years. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1061–3.

Biedenbach DJ, Moet GJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance pattern comparisons among bloodstream infection isolates from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2002). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;50:59–69.

Kim YK, Pai H, Lee HJ, Park SE, Choi EH, Kim J, et al. Bloodstream infections by extended-spectrum β- lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in children: epidemiology and clinical outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1481–91.

Blomberg B, Jureen R, Manji KP, Tamim BS, Mwakagile DS, Urassa WK, et al. High rate of fatal patients of pediatric septicemia caused by gram-negative bacteria with extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:745–9.

Graffunder EM, Preston KE, Evans AM, Venezia RA. Risk factors associated with extended- spectrum beta- lactamase-producing organisms at a tertiary care hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:139–45.

Goyal A, Prasad KN, Prasad A, Gupta S, Ghoshal U, Ayyagari A. Extended spectrum β-lactamases in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae and associated risk factors. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:695–700.

Pfaller MA, Segreti J. Overview of the epidemiological profile and laboratory detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:153–63.

Benner KW, Prabhakaran P, Lowros AS. Epidemiology of infections due to extended-spectrum Beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in a pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:83–90.

Zaoutis TE, Goyal M, Chu JH, Coffin SE, Bell LM, Nachamkin I, et al. Risk factors for and outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species in children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:942–9.

Goodman KE, Lessler J, Cosgrove SE, Harris AD, Lautenbach E, Han JH, et al. Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. A Clinical Decision Tree to Predict Whether a Bacteremic Patient Is Infected With an Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Organism. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:896–903.

Dayan N, Dabbah H, Weissman I, Aga I, Even L, Glikman D. Urinary tract infections caused by community-acquired extended-spectrum beta- lactamase-producing and nonproducing bacteria: a comparative study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1417–21.

Kizilca O, Siraneci R, Yilmaz A, Hatipoglu N, Ozturk E, Kiyak A, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired urinary tract infection caused by ESBL-producing bacteria in children. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:858–62.

Bitsori M, Maraki S, Kalmanti M, Galanakis E. Resistance against broad-spectrum beta-lactams among uropathogens in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:2381–6.

Jhaveri R, Bronstein D, Sollod J, Kitchen C, Krogstad P. Outcome of infections with extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing organisms in children. J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2008;3:229–33.

Zerr DM, Miles-Jay A, Kronman MP, Zhou C, Adler AL, Haaland W, et al. Previous Antibiotic Exposure Increases Risk of Infection with Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase- and AmpC-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Pediatric Patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;20(60):4237–43.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

STB, KA and YO participated in the design of the study, and drafted the manuscript. AB and BS monitored data collection for the whole study. STB and EKO carried out data collection. YO and EKO helped in performing the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. ABC, AK and MC participated in the coordination, helped to draft the manuscript and reviewed last version of the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by Ethical Committee of the Hacettepe University (Approval number: GO16/94–02). The study is retrospective, the ethical committee waive a consent for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanır Basaranoglu, S., Ozsurekci, Y., Aykac, K. et al. A comparison of blood stream infections with extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and non-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in pediatric patients. Ital J Pediatr 43, 79 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-017-0398-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-017-0398-0