Abstract

Background

Trauma systems and regionalized trauma care have been shown to improve outcome in severely injured trauma patients. The aim of this study was to evaluate the implementation of a prehospital trauma care protocol and transport directive, and to determine its effects on the number of primary admissions and secondary trauma transfers in a large Scandinavian city.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational study based on local trauma registries and hospital and ambulance records in Stockholm County; patients > 15 years of age with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) > 15 transported to any emergency care hospitals in the Stockholm area were included for the years 2006 and 2008. We also included secondary transferred patients to the regional trauma center during 2006, 2008, and 2013.

Results

A total of 693 primarily admitted trauma patients were included for the years 2006 and 2008. For the years 2006, 2008 and 2013, we included 114 secondarily transported trauma patients. The number of primary patient transports to the trauma center increased during the years by 20.2 %, (p < 0.001); patients primarily transported to the trauma center had a significantly higher Injury Severity Score in 2008 than in 2006, and the number of patients transported secondarily to the trauma center in 2006 was higher compared to 2008 and to 2013 (p < 0.001, all 3 years).

Discussion

Our data indicate that implementation of a prehospital trauma care protocol may have an effect on transportation of severely injured trauma patients. A decrease in secondarily transported trauma patients to the regional trauma center was noted after 1 year and persisted at 7 years after the organizational change. Patients primarily admitted to the trauma center after the change had more severe injuries than patients transported to other emergency hospitals in the area even if 20 % of patients were not admitted primarily to a trauma center. This does not imply that the transport directives or the criteria were not followed but rather reveals the difficulties and uncertainties of field triage.

Conclusions

With the introduction of a prehospital trauma transport directive in a large urban city, an increase in patients transported to the regional trauma center and a decrease in secondary transfers were detected, but a considerable number of severely injured patients were still transported to local hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Injury is a major cause of death among individuals under 45 years of age worldwide [1]. Trauma systems and regionalized trauma care have been shown to have an impact on the outcome of trauma [2–8]. The term “trauma system” refers to a way of organizing trauma care in a specific region and includes strategies for injury prevention, protocols for prehospital assessment, ambulance transport directives, a trauma center, post-trauma care, and follow-up [6, 9].

The assessment triage is an essential part of a trauma system and is aimed at determining the need for specialist trauma care. Previous studies have shown that critically injured trauma patients benefit from treatment at a trauma center [2, 5, 10]. Improved outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, shorter intensive care periods, and a shorter total length of stay (LOS) have been seen after implementation of trauma systems [11–14]. Both overtriage and undertriage may have an unfavorable impact on the system. Undertriage can result in an increase in secondary (i.e. inter-hospital) transfers and suboptimal care for severely injured patients and may also result in increased mortality [15]. An Australian study showed that older patients with fall injuries were more likely to be undertriaged [16]. On the other hand, overtriage can result in overcrowding of trauma centers and cost ineffectiveness [17, 18]. Secondary transfer of patients might have negative impact on outcomes with an increased risk for mortality [19], but the evidence is inconclusive [20]. Studies have also suggested that implementation of a trauma system can be cost-effective [21–23]. Most previous studies on trauma systems have focused on exclusive trauma systems where the patient is transported to the region’s designated trauma center. This has served the severely injured patient well, particularly in the urban regions, but has been harder to implement in non-urban settings. The focus has then shifted towards more inclusive and integrated systems where both trauma centers and non-trauma hospitals are important for delivering trauma care to the region regardless of habitation status and have the ability to match the patients’ injury with the right level of care [9, 24]. Some recent studies from Canada have focused on integrated systems [24, 25], but more research is needed to evaluate these systems in terms of performance and cost effectiveness. The majority of the studies on trauma systems and trauma outcomes have been conducted outside of Europe [26] and Scandinavia [27] therefore the results may not be applicable to our slightly different trauma systems.

The Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in Stockholm implemented a new prehospital trauma care protocol on July 1st, 2007, which included a new prehospital regional trauma transport directive to transport of the most severely injured patients to Karolinska University Hospital at Solna, the single trauma center in the Stockholm area. Prior to this directive, all trauma patients, regardless of injury type or severity, were transported to the nearest hospital without taking into consideration the receiving hospital’s capability in terms of skills, staffing, training, and competence in caring for severely or multiple-injured patients [28].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect on patient flow to the trauma center after implementation of a prehospital trauma care protocol in a large Scandinavian city. The hypothesis was that the trauma care protocol and trauma transport directive would steer critically injured patients directly to the trauma center (primary outcome) and reduce the number of secondary transfers (secondary outcome).

Methods

We performed a retrospective register study comparing the periods January 1st–December 31st, 2006, and January 1st–December 31st, 2008, i.e., 1 year before and 1 year after the organizational changes were made. To evaluate changes over time of the system, the period from January 1st to December 31st, 2013, was compared to the years 2006 and 2008 regarding secondarily transferred patients.

Setting

This study was conducted in the Stockholm County Council (SCC) area in Sweden. This area comprises approximately 2 million inhabitants, which is about one fifth of the Swedish population, and consists of 26 municipalities with an area of 6519 square kilometers, including an archipelago of approximately 30,000 islands of various sizes [29]. The SCC is responsible for all healthcare provided in the region, including prehospital trauma care.

In the SCC area, there are seven emergency hospitals, but only one can be regarded as a level-1 trauma center according to the American College of Surgeons’ criteria, namely Karolinska University Hospital, Solna. Distances from the other emergency hospitals to the trauma center vary between 5 km and 67 km.

The acute care hospitals’ emergency departments (EDs) used a variety of triage systems in 2006, where patients were categorized as triage level 1–4/5, depending on the hospital system. A more uniform system was implemented in all EDs in 2008, where all patients were triaged into 5 categories: red = 1, orange = 2, yellow = 3, green = 4, and blue = no triage needed. The same system was still in use in 2013.

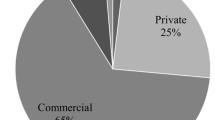

The EMS in the studied area is run by both SCC and private companies, all of them governmental funded. During 2006 and 2008, the EMS constituted 55 ground ambulances, one ambulance helicopter, one mobile intensive care unit (MICU), and three rapid response cars operating in the area (57). A rapid response car was called to severe accidents as second tier providing early advanced resuscitation assisting the crew of the regular ambulances. In 2008, it became mandatory to man the ambulances with a specialist nurse (prehospital emergency medicine, anesthesiology or intensive care). From 2008 to 2013, the number of ground ambulances had increased to 61, but the staffing and training were identical to 2008 (Table 1).

Study population

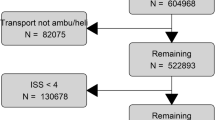

In the first two study periods (2006 and 2008) we included adult trauma patients (>15 years of age) with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) > 15, transported by ground or helicopter ambulance to any of the seven emergency hospitals in the Stockholm area. For 2013 we included only adult trauma patients (>15 years of age) with ISS > 15 secondarily transferred to the Karolinska University Hospital Trauma Center within 24 h from the injury. This secondary transfer data from 2013 was included as a “marker” how the system has maturated over the years since it was introduced.

Patients with traumatic cardiac arrest and ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during transport to hospital were included even if no return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) occurred during transport. We excluded trauma patients who were declared clinically dead on-scene for whom no resuscitative measures were taken, patients admitted to the reporting hospital > 24 h after the trauma, and patients suffering asphyxia due to drowning.

Primary admissions were defined as patients transported directly from the scene to trauma center within 24 h after trauma; secondary transfers were defined as patients transferred from any other hospital within 24 h after trauma to the trauma center.

Excluded secondary transfers were those involving patients from another county for specialist care and/or transfers > 24 h after the initial admission to a local hospital.

We included variables according to the Utstein template for major trauma [30]: age, gender, dominating type of injury, injury mechanism, intentional injury, systolic blood pressure at arrival on scene, respiratory rate at arrival on scene and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score [31] at arrival on scene, prehospital cardiac arrest, type of prehospital transportation, and inter-hospital transfers (i.e. secondary transfers). In addition, the following variables were added for the purpose of this study: prehospital triage level, prehospital priority and the Injury Severity Score (ISS) [32].

The prehospital trauma care protocol

The prehospital guidelines for trauma triage before July 1st, 2007, included only anatomical and descriptive criteria concerning the injury mechanism and were used to alert the receiving hospital for an incoming trauma patient. There was no actual protocol and the triage was based on the EMS crew’s clinical observation of the patient.

The triage protocol implemented in 2007 included vital parameters, i.e., whether the systolic blood pressure was less than 90 mmHg, the respiratory rate below 10 or higher than 29, or the Glascow Coma Scale (GCS) score was less than 14, and stated that the trauma patient should be transported to the trauma center directly regardless of bypassing the nearest hospital. If the patient had normal vital parameters, the anatomical injuries should be assessed and the trauma mechanism should be regarded as part of the criteria (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Data for 2006 and 2008 were collected from trauma registry “Kvalitet i Trauma Sjukvården”, KVITTRA/QUITC (version 14.0) at the Karolinska University Hospital (Solna and Huddinge). The data on secondary transfers for years 2006, 2008 and 2013 were collected from the Trauma Registry at the Trauma Center.

Data from the second largest hospital in the area, Södersjukhuset, were collected from the trauma registry TRAUMAREG (version TraumaSys 2000–2001, version 1.1.), and completed by data from the hospital’s digital patient registration system (Pasett-DRG, version 1.61) regarding length of stay. Data from the four other local hospitals were retrieved from the digital patient records (Take Care, Melior, and Cambio Cosmic), and trauma patients identified from emergency department records. Since no uniform reporting system or term for admitted trauma patients existed, the records were examined manually. Records of all patients transported by ambulance or helicopter to the surgical or orthopedic sections of the emergency departments and with a traumatic injury mechanism, and ED priority level of 1 or 2 and/or admitted to a hospital ward were examined for injury severity. In addition, all patients with suspected head trauma or patients directly admitted to the ICU or operating room from the ED were scanned, regardless of the priority given at the ED. In one hospital it was not possible to obtain all hospital admission records and therefore only pre-alert trauma patients were examined for eligibility. Prehospital data were collected from the digital ambulance records (CAK-net) used by all ambulance caregivers in SCC. The data collection is shown in Table 1.

The patients were identified through their unique Swedish social security number. Foreign patients received a temporary number given by the admitting hospital, making it possible to track these patients between hospitals in case of a secondary transfer. For patients included from the four hospitals without trauma registries the Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS, version 2005) [33] and the Injury Severity Score (ISS) [32] were calculated by trained trauma registry personnel and by one of the authors (RRW).

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (Reg. Nos: 2007/1113-31; 2010/1979-32, 2013/1718-32 and 2014/691-32).

Statistics

Continuous variables are presented with the median, mean and interquartile range (IQR), range and categorical variables, with the count (n) and percentage (%). Since none of the variables were normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous data and chi-square for categorical data. Data were statistically analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0.0.0. The statistical level of significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

Three hundred and ten patients were included from 2006, and 383 patients from 2008 (Table 2). The majority of the injuries were due to blunt trauma and the predominant injury mechanism was traffic-related during both years. No difference in gender or age distribution was noted. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the study population. The median ISS was significantly lower in 2006 than in 2008 (20 and 24, respectively, p < 0.001). The priority of ambulance transports did not differ between the years, nor did the number of prehospital traumatic cardiac arrests (Table 3).

The number of patients transported to the trauma center increased between the years by 20.2 %, i.e., from n = 189 patients to n = 307, p < 0.001. Table 4, as well as Fig. 2, displays both the distribution of patients transported directly to the trauma center and transports to the non-trauma center hospitals. Patients transported to the trauma center had a significantly higher ISS score in 2008 than in 2006 (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Secondary transfers decreased significantly between years 2006 (n = 47) and 2008 (n = 32) (p < 0.001), but no further decrease was noted in 2013 (n = 35). There were no significant differences in age or ISS for the secondary transferred patients between the studied periods and the majority of the patients were males during all three studied periods.

Discussion

The results of this study indicates that implementation of a prehospital trauma care protocol in a large urban city may have an effect on primary transportation rates of severely injured trauma patients. A decrease in secondary transfers to the regional trauma center was seen after 1 year and persisted 7 years after the organizational changes. Patients primarily admitted to the trauma center after the change were more severely injured than patients transported to other emergency hospitals in the area.

A study from New South Wales in Australia evaluating a modified version of the ACS-COT prehospital trauma triage protocol reported that approximately a quarter of the patients injured in an urban area were transported to a non-trauma hospital [34]. This study is particularly interesting since the trauma triage protocol they implemented has similarities to the protocol we have studied. However, in our study, we focused on evaluating the ability of the new trauma system to direct severe trauma patients to the trauma center and did not evaluate the actual performance of the protocol criteria. Therefore, with almost 20 % of the patients still not being transported direct to the trauma center in 2008, there is a possibility that the performance of the new triage protocol was not optimal.

Demetriades [35] and Meisler et al. have reported that early transfer to a trauma center might improve survival [36]. Further, Nirula et al. have concluded that secondary transfers from a non-trauma hospital to a trauma center increases the risk of mortality [7] as compared to primary admissions. All patients in our sample were severely traumatized (ISS score > 15), which makes it is fair to assume that the majority of these patients would benefit from trauma center care.

Cudnik et al. reported improved survival and better functional outcomes for injured patients transported directly to a level I trauma center, compared to those taken to a level II center [5]. They also showed that patients with an intracranial injury and/or skull fracture, as well as patients with pelvic fractures, had a better outcome when treated at a level I center. The same was demonstrated by Demetriades et al. [35] and Garwe et al., who reported a survival benefit for patients transferred to a level I facility from level III or IV facilities [10]. Some studies have reported transportation of severely injured patients to non-trauma centers with proportions between 30 % and 60 % [23, 37], but others have reported no survival benefit from direct transportation to a trauma center [38–41]. However, Haas et al. [22] have pointed out that the value of these studies is limited due to the fact that they were based on data from trauma registries where no account was taken of patients who died before transfer. They showed that for inter-facility transfers that included patients who died while waiting for transfer, the mortality rate increased by 25 % and concluded that undertriage was associated with higher mortality and that primary admissions to a trauma center was beneficial. In our study 20 % of patients were not admitted primarily to a trauma center. However, we believe that this fact does not mean that the transport directives or the criteria were not followed since this study did was not designed to evaluate the criteria as such. We believe that the results mainly imply the difficulties and uncertainties of field triage, an area where further research is needed.

Our study has a retrospective design with the majority of the data collected from trauma registries. There is a possibility of missing cases, which might be a limitation. However, trauma documentation was a prioritized area for the hospitals during the periods included in our study, with educated trauma registrars being responsible for data collection. During the studied years, some changes were made in the EMS system. In 2008 and 2013, the ambulance crews consisted of at least one nurse with specialist training, which was not the case in 2006. A new trauma care protocol was implemented at the receiving hospitals’ EDs between the data collection years, with triage levels corresponding to the new trauma protocol in the prehospital system, while in 2006 all EDs still had their own independent triage systems, a fact that made it more difficult to compare triage levels between hospitals. One of the hospitals did not have a system that allowed us to retrieve full admission records for the years studied, which made it impossible to scan triage levels for injury severity among all patients admitted to the surgical and orthopedic sections of the ED, or for head traumas.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to evaluate the effect of a new trauma care protocol and transport directive for trauma patients in our region. It is necessary for a trauma system to mature for several years and further evaluation of the system will be needed. The goal of a trauma system is to get the right patient to the right facility at the right time. Studying how a trauma system works is the key to achieve this.

Conclusions

This study focusing on the effects of implementing an improved trauma care protocol and a trauma transport directive in a large urban city indicates an increased frequency of patients primarily admitted to the regional trauma center and a decrease in secondary transfers. Nonetheless, almost 20 % of the severely injured patients were still transported to the emergency hospitals after implementation. Based on these findings, our system of regionalized trauma care and expedite immediate trauma center admission will be further improved.

Abbreviations

- ACOS:

-

American College of Surgeons

- AIS:

-

abbreviated injury scale

- CPR:

-

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- ED:

-

emergency department

- EMS:

-

emergency medical services

- EMT:

-

emergency medical technicians

- GCS:

-

glasgow coma scale

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- ISS:

-

injury severity score

- KSS:

-

Karolinska University Hospital in Solna

- KVITTRA/QUITC:

-

quality in trauma care

- LOS:

-

length of stay (days)

- MICU:

-

mobile intensive care unit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ROSC:

-

return of spontaneous circulation

- RTS:

-

revised trauma score

- RR:

-

respiratory rate

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- SCC:

-

Stockholm County Council

References

Soreide K. Epidemiology of major trauma. Br J Surg. 2009;96(7):697–8.

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):366–78.

Shackford SR, Hollingworth-Fridlund P, Cooper GF, Eastman AB. The effect of regionalization upon the quality of trauma care as assessed by concurrent audit before and after institution of a trauma system: a preliminary report. J Trauma. 1986;26(9):812–20.

Sampalis JS, Denis R, Lavoie A, Frechette P, Boukas S, Nikolis A, et al. Trauma care regionalization: a process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):565–79. discussion 579-581.

Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Sayre MR, Steinberg SM. Level I versus Level II trauma centers: an outcomes-based assessment. J Trauma. 2009;66(5):1321–6.

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV. Effectiveness of state trauma systems in reducing injury-related mortality: a national evaluation. J Trauma. 2000;48(1):25–30. discussion 30-21.

Nirula R, Maier R, Moore E, Sperry J, Gentilello L. Scoop and run to the trauma center or stay and play at the local hospital: hospital transfer’s effect on mortality. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):595–9. discussion 599-601.

Mackenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Egleston BL, Salkever DS, et al. The impact of trauma-center care on functional outcomes following major lower-limb trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):101–9.

Rotondo MF, Cribari C, Smith RS. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma: Resources for the Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014. 6th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014.

Garwe T, Cowan LD, Neas B, Cathey T, Danford BC, Greenawalt P. Survival benefit of transfer to tertiary trauma centers for major trauma patients initially presenting to nontertiary trauma centers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(11):1223–32.

Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60(2):371–8. discussion 378.

Papa L, Langland-Orban B, Kallenborn C, Tepas JJ, Lottenberg L, Celso B, et al. Assessing effectiveness of a mature trauma system: Association of trauma center presence with lower injury mortality rate. J Trauma. 2006;61(2):261–6. discussion 266-267.

Newgard CD, McConnell KJ, Hedges JR, Mullins RJ. The benefit of higher level of care transfer of injured patients from nontertiary hospital emergency departments. J Trauma. 2007;63(5):965–71.

Liberman M, Mulder DS, Lavoie A, Sampalis JS. Implementation of a trauma care system: evolution through evaluation. J Trauma. 2004;56(6):1330–5.

Haas B, Stukel TA, Gomez D, Zagorski B, De Mestral C, Sharma SV, et al. The mortality benefit of direct trauma center transport in a regional trauma system: a population-based analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1510–5. discussion 1515-1517.

Dinh MM, Oliver M, Bein KJ, Roncal S, Byrne CM. Performance of the New South Wales Ambulance Service major trauma transport protocol (T1) at an inner city trauma centre. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(4):401–7.

Ciesla DJ, Sava JA, Street 3rd JH, Jordan MH. Secondary overtriage: a consequence of an immature trauma system. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):131–7.

Newgard CD, Staudenmayer K, Hsia RY, Mann NC, Bulger EM, Holmes JF, et al. The cost of overtriage: more than one-third of low-risk injured patients were taken to major trauma centers. Health Aff. 2013;32(9):1591–9.

Mans S, Reinders Folmer E, de Jongh MA, Lansink KW. Direct transport versus inter hospital transfer of severely injured trauma patients. Injury. 2016;47(1):26–31.

Hill AD, Fowler RA, Nathens AB. Impact of interhospital transfer on outcomes for trauma patients: a systematic review. J Trauma. 2011;71(6):1885–900. discussion 1901.

MacKenzie EJ, Weir S, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Wang W, et al. The value of trauma center care. J Trauma. 2010;69(1):1–10.

Haas B, Gomez D, Zagorski B, Stukel TA, Rubenfeld GD, Nathens AB. Survival of the fittest: the hidden cost of undertriage of major trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(6):804–11.

Durham R, Pracht E, Orban B, Lottenburg L, Tepas J, Flint L. Evaluation of a mature trauma system. Ann Surg. 2006;243(6):775–83. discussion 783-775.

Kuimi BL, Moore L, Cisse B, Gagne M, Lavoie A, Bourgeois G, et al. Influence of access to an integrated trauma system on in-hospital mortality and length of stay. Injury. 2015;46(7):1257–61.

Kuimi BL, Moore L, Cisse B, Gagne M, Lavoie A, Bourgeois G, et al. Access to a Canadian provincial integrated trauma system: a population-based cohort study. Injury. 2015;46(4):595–601.

Metcalfe D, Bouamra O, Parsons NR, Aletrari MO, Lecky FE, Costa ML. Effect of regional trauma centralization on volume, injury severity and outcomes of injured patients admitted to trauma centres. Br J Surg. 2014;101(8):959–64.

Kristiansen T, Soreide K, Ringdal KG, Rehn M, Kruger AJ, Reite A, et al. Trauma systems and early management of severe injuries in Scandinavia: review of the current state. Injury. 2010;41(5):444–52.

Medicinska riktlinjer 2012 [http://www.webbhotell.sll.se/PageFiles/24574/Medicinska%20behandlingsriktlinjer%20SLL%202012.pdf]

sll.se [sll.se [internet]. Stockholms läns landsting cited 2013 oct 1]. Available from: http://www.sll.se]

Ringdal KG, Coats TJ, Lefering R, Di Bartolomeo S, Steen PA, Roise O, et al. The Utstein template for uniform reporting of data following major trauma: a joint revision by SCANTEM, TARN, DGU-TR and RITG. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2008;16:7.

Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81.

Osler T, Baker SP, Long W. A modification of the injury severity score that both improves accuracy and simplifies scoring. J Trauma. 1997;43(6):922–5. discussion 925-926.

Gennarelli TA, Wodzin E. AIS 2005- Abbreviated Injury Scale, Update 2008. Barrington: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 2005.

Fitzharris M, Stevenson M, Middleton P, Sinclair G. Adherence with the pre-hospital triage protocol in the transport of injured patients in an urban setting. Injury. 2012;43(9):1368–76.

Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A, Rhee P, Brown C, Doucet J, et al. Relationship between American College of Surgeons trauma center designation and mortality in patients with severe trauma (injury severity score > 15). J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(2):212–5. quiz A245.

Meisler R, Thomsen AB, Abildstrøm H, Guldstad N, Borge P, Rasmussen SW, et al. Triage and mortality in 2875 consecutive trauma patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(2):218–23.

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP. A resource-based assessment of trauma care in the United States. J Trauma. 2004;56(1):173–8. discussion 178.

Nathens AB, Maier RV, Brundage SI, Jurkovich GJ, Grossman DC. The effect of interfacility transfer on outcome in an urban trauma system. J Trauma. 2003;55(3):444–9.

Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Wang J, Nathens A, Jurkovich GA, Mackenzie EJ. Outcomes of trauma patients after transfer to a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2008;64(6):1594–9.

Moen KG, Klepstad P, Skandsen T, Fredriksli OA, Vik A. Direct transport versus interhospital transfer of patients with severe head injury in Norway. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(5):249–55.

Hesselfeldt R, Steinmetz J, Jans H, Jacobsson ML, Andersen DL, Buggeskov K, et al. Impact of a physician-staffed helicopter on a regional trauma system: a prospective, controlled, observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(5):660–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hans Järnbert Petterson, PhD and statistician, and Lina Benson, statisticians at Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Science and Education, Södersjukhuset, for their assistance in the statistical analyses, Milka Dinevik, controller at the ambulance service company, AISAB (Ambulanssjukvården i Storstockholm AB), and Ellinor Berglund, RN, study nurse for help in collecting data. We also thank Olof Brattström MD, PhD from Karolinska University Hospital for help with data from the trauma registry. This study was supported by grants provided by the Stockholm County Council (ALF project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RRW conceived the study, participated in the design of the study and coordination, collected the data, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SP participated in the design of the study, provided methodological and statistical support, and helped in drafting the manuscript. MS participated in the design of the study and helped in drafting the manuscript. HML provided support to the design and helped in drafting the manuscript. MC conceived the study, participated in its design and helped in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubenson Wahlin, R., Ponzer, S., Skrifvars, M.B. et al. Effect of an organizational change in a prehospital trauma care protocol and trauma transport directive in a large urban city: a before and after study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 24, 26 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0218-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0218-3