Abstract

Background

Although cases of cervical squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the ovary have been previously documented, we report the first case of superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the ovary.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman with a two-year history of ovarian endometriosis confirmed by ultrasound underwent oophorectomy. On microscopic examination, a focus of malignant stratified epithelium, initially interpreted as transitional cell carcinoma, was identified within the endometriotic cyst wall. Examination of the hysterectomy specimen revealed superficially invasive squamous carcinoma of the cervix. In addition, two triploid, CD45-negative cells were detected during the analysis of the peripheral blood for circulating tumor cells (CTC). High-risk HPV was detected on the sections of endometriosis containing cancerous area by using hybrid capture 2 assay, supporting the diagnosis of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma originating from the uterine cervix.

Conclusion

This is the first report of superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the ovary. Such finding could be misdiagnosed as primary ovarian transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma originating from metaplastic epithelium within endometriosis, or squamous cell carcinoma arising in a teratoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ovarian metastases from cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) are rare. They account for less than 1% of metastatic tumors in the ovary and typically occur in advanced stage cervical carcinoma. Only rare cases of ovarian metastasis from superficially invasive SCCA have been documented in the English literature [1,2,3,4,5]. To our knowledge, no cases of SCCA metastases to the ovary involving structures other than native ovarian tissue have been previously documented. We report a case of an incidental metastatic cervical superficial squamous cell carcinoma to the ovarian endometriosis.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman presented for a routine physical examination. Her pelvic ultrasound revealed a 4.2 cm left ovarian cyst. Initially, the lesion was managed conservatively with observation. Over the next 2 years, the patient remained free of symptoms; however, her ovarian cyst doubled in size measuring 8.1 cm by ultrasound. A laparoscopic left oophorectomy was ultimately performed.

Pathologic findings

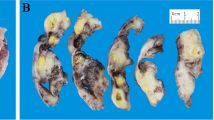

Intraoperative pathologic evaluation revealed dark red cyst wall fragments, 7 cm in aggregate, and an unremarkable fallopian tube (Fig. 1a). The frozen section diagnosis was ovarian endometriosis (Fig. 1b), confirmed by evaluation of permanent sections. Among multiple additional permanent sections, several sections demonstrated atypical stratified epithelium in the subepithelial stroma within the cystic wall. The atypical cells had large, hyperchromatic nuclei, irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and numerous mitoses, consistent with malignant cells (Fig. 2a-c). The total size of malignant epithelium was approximately 15 mm. The remainder of the specimen was entirely submitted for microscopic examination and demonstrated ovarian tissue with endometriosis and an unremarkable fallopian tube. No evidence of teratoma was identified.

Carcinoma within endometriotic cyst wall. a Malignant epithelium lining the cyst wall and forming nests in the subepithelial stroma (H&E, × 40); b, c Malignant cells demonstrate large, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and increased mitoses (H&E, B:× 100; C × 200)

By immunohistochemistry (IHC), the malignant cells were diffusely positive for CK7, CK5/6, p63, and p16, and negative for CK20, WT1, GATA3, ER, and PR. p53 demonstrated wild-type staining pattern. Ki67 proliferation index was approximately 50%. (Fig. 3a-h).

Based on the morphologic features and immunohistochemical stain findings, the case was diagnosed as ovarian transitional cell carcinoma-like high-grade serous carcinoma. A differential diagnosis of metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract was entertained; however, no lesions were identified in the urinary tract by ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) scan. To rule out squamous cell carcinoma arising from teratoma, the entire specimen was examined. No evidence of teratoma was identified. The patient sought external pathology consultations from two large regional medical centers, both of which agreed with the original diagnosis.

Total hysterectomy and right salpingo-oophorectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection and omentectomy were performed. Grossly, the uterus, cervix, right ovary and fallopian tube were unremarkable (Fig. 4a). Microscopically, the right ovary, right fallopian tube, and other specimens revealed no evidence of malignancy. Interestingly, representative sections of the cervix revealed high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Eventually the cervix was entirely submitted for microscopic examination. Additional cervical sections demonstrated HSIL with focal superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The depth of invasion was 4.0 mm and a horizontal extent was 6.0 mm involving only one of total 12 sections of the cervix. No lymphovascular invasion was identified. Examination of the right ovary revealed no evidence of teratoma. The FIGO tumor stage was IA2 (Fig. 4b-c). Prior to hysterectomy, testing for high-risk HPV was performed on the cervical cytology specimen by hybrid capture2 (HC2) method (Qiagen Inc., USA), and was positive (935 RLU; reference range: < 1.00RLU).

Uterine cervix with HSIL with focal superficially invasive squamous carcinoma. a Gross examination of the uterus demonstrated no abnormalities; b, c Sections of the cervix demonstrated HSIL with focal superficially invasive squamous carcinoma (H&E, × 100). d Analysis of the peripheral blood for circulating tumor cells detected two triploid CD45-negative malignant cells by FISH (× 400)

The original diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma-like high-grade serous carcinoma was questioned. To correlate the findings in the ovary and cervix, DNA extraction was performed from the ovarian sections with carcinoma. The DNA extraction and purification was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using GenElute™ FFPE DNA Purification Kit (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, USA). Testing for high-risk HPV was performed by HC2 method was positive (141.3 RLU; reference range: < 1.00 RLU).

To further support the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma, analysis of the patient’s peripheral blood for circulating tumor cells (CTC) was performed. Several malignant, triploid, CD45-negative epithelial cells were identified, suggestive of the presence of carcinoma cells in the peripheral blood (Fig. 4d).

The final diagnosis was metastatic cervical squamous cell carcinoma involving ovarian endometriosis.

Discussion

Ovarian metastases from cervical carcinoma occur in 5.3–8.2% cases of endocervical adenocarcinoma and 0.4–1.3% of squamous cell carcinoma [2, 6, 7]. The possible routes of cervical cancer spread to the ovary include direct extension, lymphatic and hematogenous spread, and trans-tubal migration. A few factors increase the risk for ovarian metastases. These include two independent factors, cancer type (adenocarcinoma greater than squamous cell carcinoma) and involvement of the uterine corpus. Additional factors increasing metastatic potential are vaginal involvement, lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastases [6, 8].

Ovarian involvement is directly related to the stage of cervical carcinoma. It ranges from 0.22% for stage IB squamous cell carcinoma to 9.8% for stage IIB adenocarcinoma [2, 9, 10]. Stage IA carcinomas metastasize to the ovaries rarely, with only a few reports in the literature [11]. Young et al. reported a case of squamous cell carcinoma in situ with right ovarian surface involvement [12]. But, the majority of reported cases describe advanced stage carcinomas involving the ovary after the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma was previously established in cervical LEEP or cold knife cone excision specimens. In our patient, the ovarian metastasis was an incidental finding. This case illustrates the importance of cervical cancer screening regardless of the presence of symptoms.

An additional, interesting finding was the involvement of the endometriotic cyst wall by carcinoma with sparing of the normal ovarian parenchyma. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case describing this unusual pattern of metastasis. The metastatic focus was very small and could be potentially overlooked. It was not visible on gross examination due to its small size, obscuring hemorrhage and discoloration due to endometriosis. In our case, the frozen section did not contain the metastasis. In addition, due to the rarity of squamous cell carcinoma metastases to the ovary and the overlapping immunostaining pattern (strong positivity for p16 and CK7), the tumor was initially misclassified as primary ovarian transitional cell-like high-grade serous carcinoma [13,14,15,16,17]. The diagnosis of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma was eventually established with the aid of the high-risk HPV test, which was positive in both the cervical and ovarian carcinoma.

Conclusion

This is the first report of microinvasive cervical squamous cell carcinoma with a metastasis involving exclusively an ovarian endometriotic cyst wall. In the absence of a prior abnormal cervical screening history and any visible cervical lesions, such a case may be readily misdiagnosed as another type of carcinoma. In our case, a definitive diagnosis was successfully established by careful examination of the entire uterine cervix and comparing the HPV status of the primary and metastatic tumors. This case highlights the morphological similarity between SCCA and other types of primary ovarian cancer. A high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid a misdiagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma, high-grade serous carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma arising from teratoma. Testing for high-risk HPV is helpful in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTC:

-

Circulating tumor cells

- FFPE:

-

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded

- FIGO:

-

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin-eosin

- HC2:

-

Hybrid Capture 2

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- HSIL:

-

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- LEEP:

-

Loop electrosurgical excisional procedure

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- US:

-

Ultrasound

References

Wu HS, Yen MS, Lai CR, Ng HT. Ovarian metastasis from cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;57:173.

Shimada M, Kigawa J, Nishimura R, Yamaguchi S, Kuzuya K. Ovarian metastasis in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:234.

Kang WD, Kim CH, Cho MK, Kim JW, Kim YH, Choi HS, Kim SM. Unilateral ovarian metastasis in a case of squamous cervical carcinoma IA1. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:824.

Ronnett BM, Yemelyanova AV, Vang R, Gilks CB, Miller D, Gravitt PE, Kurman RJ. Endocervical adenocarcinomas with ovarian metastases: analysis of 29 cases with emphasis on minimally invasive cervical tumors and the ability of the metastases to simulate primary ovarian neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1835.

Ramalingam P, Malpica A, Deavers MT. Mixed endocervical adenocarcinoma and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix with ovarian metastasis of the former component: a report of 2 cases. International journal of gynecological pathology official journal of the International Society of Gynecological. Pathologists. 2012;31:490.

Yamamoto R, Okamoto K, Yukiharu T, Kaneuchi M, Negishi H, Sakuragi N, Fujimoto S. A study of risk factors for ovarian metastases in stage IB–IIIB cervical carcinoma and analysis of ovarian function after a transposition. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:312.

Nakanishi T, Wakai K, Ishikawa H, Nawa A, Suzuki Y, Nakamura S, Kuzuya K. A comparison of ovarian metastasis between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:504.

Kim M, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park N, Song Y, Kang S. Uterine corpus involvement as well as histologic type is an independent predictor of ovarian metastasis in uterine cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2008;19:181.

Belinson JL, Mcclure M, Badger G. Randomized trial of megestrol acetate vs. megestrol acetate/tamoxifen for the management of progressive or recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;28:151.

Abe A, Furuta R, Takazawa Y, Kondo E, Umayahara K, Takeshima N. A Case of Ovarian Metastasis from Microinvasive Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix. Gynecol Obstet. 2014;4:248.

Ngamcherttakul V, Ruengkhachorn I. Ovarian metastasis and other ovarian neoplasms in women with cervical cancer stage IA-IIA. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;9:4525.

Young RH, Gersell DJ, Roth LM, Scully RE. Ovarian metastases from cervical carcinomas other than pure adenocarcinomas. A report of 12 cases. Cancer. 1993;71:407.

Shoji T, Takatori E, Murakami K, Kaido Y, Takeuchi S, Kikuchi A, Sugiyama T. A case of ovarian adenosquamous carcinoma arising from endometrioid adenocarcinoma: a case report and systematic review. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9:48.

Li Y, Su W, Lee W. Transitional cell carcinoma of the ovary. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:478.

Lee H, Lee H, Cho YK. Cytokeratin7 and cytokeratin19 expression in high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasm and squamous cell carcinoma and their possible association in cervical carcinogenesis. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:18.

Herfs M, Soong TR, Delvenne P, Crum CP. Deciphering the multifactorial susceptibility of mucosal junction cells to HPV infection and related carcinogenesis. Viruses. 2017;9:85.

Venyo AK. Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Adv Urol. 2014;2014:1.

Funding

This study was supported by a Scientific Research Grant from the Guangdong Science and Technology Department (No.8001201707010425) and Third affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No.8002110201701).

Availability of data and materials

The data used or analyzed are all in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QJ conceptualized the case and drafted the manuscript. EL revised the manuscript. MZ, HX and SL performed assays and formal analysis. WZ revised the manuscript. KM edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were performed in strict accordance with the Ethics Committee at Third affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. The Institutional Committee of Third affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University approved the use of all samples.

Consent for publication

Authors in the article are all agreed to the submission of this article for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Lucas, E., Xiong, H. et al. Superficially invasive cervical squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to ovarian endometriotic cyst wall, a case report and brief review of the literature. J Ovarian Res 11, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0417-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0417-9