Abstract

RAS mutations (HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS) are among the most common oncogenes, and around 19% of patients with cancer harbor RAS mutations. Cells harboring RAS mutations tend to undergo malignant transformation and exhibit malignant phenotypes. The mutational status of RAS correlates with the clinicopathological features of patients, such as mucinous type and poor differentiation, as well as response to anti-EGFR therapies in certain types of human cancers. Although RAS protein had been considered as a potential target for tumors with RAS mutations, it was once referred to as a undruggable target due to the consecutive failure in the discovery of RAS protein inhibitors. However, recent studies on the structure, signaling, and function of RAS have shed light on the development of RAS-targeting drugs, especially with the approval of Lumakras (sotorasib, AMG510) in treatment of KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC patients. Therefore, here we fully review RAS mutations in human cancer and especially focus on emerging strategies that have been recently developed for RAS-targeting therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HRAS was first regarded as oncogene due to a single-point mutation in 1982. Subsequently, NRAS and KRAS were identified quickly [1]. Since then, intense efforts have been made into the study of RAS [2]. Among the most common oncogenes regarding human cancers, mutant RAS affects approximately 19% of tumors [3].

RAS proteins belong to the family of GTPases and are considered as regulators of cellular proliferation, cell migration, apoptosis, and survival [2]. Mutant RAS proteins stimulate downstream signals and have significant oncogenic roles, and tumor cells harboring mutant RAS exhibit more aggressive phenotypes [4, 5]. Accordingly, tumor patients with mutant RAS possess a worse prognosis and shorter overall survival (OS) compared with those patients without RAS mutation [6, 7].

In clinical cancer patients, tumors harboring RAS mutations exhibit distinct clinicopathological characteristics and sensitivity to targeted therapy and chemotherapy. For example, RAS mutations are thought to correlate with features that predict aggressive behaviors, such as increased mitosis [8, 9]. RAS mutational status is also correlated with the efficiency of targeted therapy. For example, anti-EGFR therapy is unsuitable for RAS-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients [10,11,12,13]. However, whether the mutational status of RAS affects chemotherapy efficiency remains controversial.

Direct targeting of RAS proteins used to be considered impossible because of the lack of drug-binding pockets on the surface of RAS proteins. However, great efforts are being made to determine various targeting strategies including: (1) targeting upstream molecules (e.g., PDE δ, SHP2, and STK19); (2) targeting the RAS proteins directly (e.g., by chemical compound or antibody); (3) targeting the downstream effectors (e.g., RAF, MEK, ERK, PI3K, and combined inhibition); (4) RNA interference (RNAi) of RAS expression; (5) targeting the distinct metabolic processes correlated with RAS mutation (e.g., micropinocytosis and autophagy); and (6) screening for synthetic lethal interactors [14]. In certain types of cancers, an objective response has been observed, including for KRASG12C inhibitors AMG510 and MRTX849 in KRASG12C-mutant lung or colorectal cancer patients, for the SRC homology-2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2) inhibitor RMC-4630 in advanced NSCLC patients harboring KRAS mutation and for RAS/MEK inhibitor RO5126766 (VS-6766) combination with FAK inhibitor in KRAS mutation low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC) [15,16,17]. Remarkedly, based on a study of 124 advanced NSCLC patients harboring KRASG12C mutation, Lumakras (sotorasib, AMG510) were approved for KRASG12C NSCLC patients by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently, which is the first approved targeted therapy for tumors with KRAS mutation [18, 19]. Therefore, here we fully review RAS mutations in human cancer and especially focus on emerging strategies that have been recently developed for RAS-targeted therapy.

RAS structure, function, and signaling

There are three RAS genes giving rise to four main protein products: KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS. These isoforms share highly homogenous sequences or structures, and all possess conserved G domains (aa 1–166) and C-terminal hypervariable regions (HVRs) (aa 166–188/189) (Fig. 1A). The G domain of RAS, consisting of switch I (aa 30–40), switch II (aa 60–76), and a P loop (aa 10–17), is responsible for the binding of downstream effectors to transduce downstream signals, while the C-terminal has vital role in RAS binding to membranes [20]. The final four amino acids, CAAX, of the C-terminal are the targets of posttranslational modifications, including iso-prenylation, proteolysis, and methylation which mediate RAS shift and binding to the cell membrane [21].

Structure and switch of RAS. A Structure of RAS proteins, including the effector lobe (aa 1–86), allosteric lobe (aa 87–165), and HVR (aa 167–188/189). Switch I (aa 30–40) and switch II (aa 60–76) are located in the effector lobe and function in effector binding and GEF or GAP binding. The HVR domain contributes to RAS binding to cell membranes. B Inactive GDP-bound KRAS and GTP-bound KRAS cycle. The switch to RAS-GTP is stimulated by GEF, while GAPs accelerate the termination of the active state. The active GTP-bound RAS transfers the proliferation and differentiation signals through downstream effectors such as RAF, PI3K, and RalGEFs

RAS proteins cycle between the GDP-bound inactive state (RAS-GDP) and the GTP-bound active state (RAS-GTP) (Fig. 1B). The inactive state of RAS exchanges the GDP/GTP binding when signals provoke it, and the switch to RAS-GTP is accelerated by GEFs (e.g., SOS1). The rate of the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis of RAS proteins is very slow; As a result, GAPs accelerate the termination of the active state by several orders of magnitude [22]. The active RAS-GTP, interacting with downstream effectors including RAF, PI3K, and Ral guanine exchange factors (RalGEFs), transduces the signal to regulate biological behavior [23,24,25,26]. The first two corresponding pathways, RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK and RAS–PI3K-AKT–mTORC, act as fundamental signaling pathways of RAS proteins [24]. Mutations in the three RAS isoforms, G12, G13, and Q61, can abolish the intrinsic GTPase activity of RAS and increase the GEF-mediated exchange rate [27,28,29]. As a result, RAS remains a continuously active GTP-bound state and hence is oncogenic.

RAS mutation frequency and hotspots in human cancers

RAS mutations occur in approximately 19% of all cancers, occupying a prominent role in tumorigenesis and tumor progression [3]. Among which, KRAS is the most frequently mutated isoform, followed by NRAS, and HRAS. RAS isoform mutations show selectivity in various human cancers (Fig. 2A). For example, KRAS mutations often occur in pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma (PDAC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAC), and colon and rectal adenocarcinoma (with mutation frequencies of 66.1%, 16.5%, 30.3%, and 34.4%, respectively; COSMIC v94), whereas in hematological malignancies such as chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), NRAS mutation frequencies are relatively high at up to 13.1% and 13.6% (COSMIC v94), respectively, reflecting the rates in malignant melanoma, thyroid carcinoma, and larynx carcinoma, which have NRAS mutation frequencies of 18.6%, 8.1%, and 9.7%, respectively (COSMIC v94). Although HRAS mutations are negligible in human cancers, salivary gland carcinoma, mouth carcinoma, and vulva carcinoma possess relatively high rates of HRAS mutation.

RAS mutational frequency and hotspots in human cancer. A The mutational frequency of KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS in various cancers. B The proportion of RAS mutation hotspots. G12, G13, and Q61 occupy 96–98% of all mutations in KRAS and NRAS isoforms. The data are taken from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC v94). PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Although > 100 mutation sites have been identified in all three RAS isoforms, the most prominent mutational hotspots are G12, G13, and Q61, occupying almost 96%–98% of all mutations in KRAS and NRAS isoforms, whereas the proportion of HRAS mutations is relatively low (COSMIC v94). Furthermore, different RAS isoforms exhibit varied hotspot preference for G12, G13, and Q61. Approximately 80% of mutations reside at G12 for KRAS mutations; in contrast, Q61 mutations are more common in NRAS, accounting for 60% of all mutations. Regarding HRAS, the mutational frequency among the three sites is similar (Fig. 2B). The underlying mechanism of codon-specific RAS mutations in specific tumor types remains unclear. Recent observations indicate that codon-specific mutations that confer a fitness advantage to tumor cells may explain the selection. For example, mouse models of knocked-in NRASQ61R exhibited melanoma formation, but those with NRASG12D did not; the mechanism lied in increased GTP binding affinity and reduced intrinsic GTPase activity compared with NRASG12D [30]. In fact, the isoform, codon, and frequency of RAS mutation vary by tissue type.

Clinical implications of RAS mutations

Correlation of RAS mutations and clinicopathological features

RAS mutational status correlates with clinicopathological features. Patients harboring mutant RAS exhibit distinct phenotypes, clinical pathology classification, and staging (Table 1). RAS mutations represent aggressive biological behavior of thyroid cancer and colorectal cancer [31]. As a result, colorectal cancer patients harboring KRAS or NRAS have shorter overall survival (OS) [32]. Additionally, KRAS status will shift the metastatic profile of colorectal cancer; KRAS-mutant tumors tend to spread to the lungs, whilst wild-type tumors have a higher propensity of invasion to the liver [33, 34]. For patients with colorectal liver metastases receiving liver resection, studies have indicated that KRAS mutations correlate with worse recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS [35,36,37,38]. In melanoma, NRAS mutations correlate with the presence of mitoses, lower tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) grade, extremity location, thick tumors, and higher AJCC stage [8, 9, 39]. In ovarian cancer, significant associations are found between KRAS mutations and lower grade, mucinous histological subtype, and positive progesterone expression [40]. These findings suggest that patients with RAS mutations possess distinct clinicopathological features.

Correlations of RAS mutational status and treatment efficiency of targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy

Recent studies have identified correlations between RAS mutational status and the treatment efficiency of targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy (Table 2). KRAS mutational status predicts the response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) therapy in patients with mCRC. Patients with KRAS mutations in exons 2 do not benefit from anti-EGFR therapy; either anti-EGFR antibody alone or combined with chemotherapy [10,11,12, 41]. However, there seems to be an exception for patients with KRASG13D, who benefit from cetuximab [42, 43]. In contrast with the clear predicted significance of KRAS mutational status for anti-EGFR therapy in mCRC, whether it can be utilized in NSCLC remains controversial. An association between KRAS mutations and lack of response to anti-EGFR has been observed in the clinic [44, 45]; thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that NSCLC tumors with KRAS mutations are resistant to anti-EGFR therapy. However, increased studies have indicated that KRAS mutational status does not have predictive significance in the selection of patients for anti-EGFR therapy in NSCLC [46,47,48,49]. Therefore, KRAS mutational status currently provides insufficient evidence to recommend the selection of patients for anti-EGFR treatment in NSCLC.

Whether RAS mutational status influences chemotherapy efficiency remains unclear, and the predictive value of mutant RAS status to the response to chemotherapy is controversial [50–54]. Improved clinical response to chemotherapy was observed in KRAS-mutant patients suffering from mCRC and pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm grade-3 (PanNEN-G3) [54–56], while in other clinical trials, KRAS mutational status did not have prognostic value for stage II/III colon cancer receiving either FU/FA alone or in combination with irinotecan [52]. Further analyses from the PETACC-8 trial even suggested that KRAS mutation was associated with shorter DFS and OS for stage III colon cancer treated with leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin alone or combination with cetuximab, while in patients with microsatellite instability (MSI), KRAS mutational status did not have prognostic value [50, 53].

With the emergence of drugs targeting negative immune regulators containing programmed cell death protein 1(PD1), programmed cell death 1 ligand 1(PD-L1), or cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), immune therapy represented by immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has revolutionized cancer treatment [57]. It has been found that high PD-L1 expression was significantly correlated with the presence of KRAS mutations in pulmonary sarcomatous carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma [58, 59], indicating that patients with KRAS mutations may exhibit a more efficient response to ICB. In addition, ICB tended to show consistently higher efficiency in KRAS-mutant NSCLC [60]. However, oncogenic KRAS promotes tumor cell immune escape and immune therapy resistance through attracting immune-suppressive cells or suppressing cytotoxic cells in a colorectal cancer mouse model [61, 62]. Therefore, whether RAS mutational status should be considered before administering ICB therapy warrants further study.

RAS targeting strategies

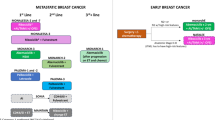

Drugging RAS proteins directly used to be considered impossible because of the lack of pockets for drug binding on the surface of RAS proteins, and hence, the focus shifted to upstream and downstream proteins of RAS with the aim of suppressing the oncogenic signal. Recent studies on RAS structure, function, and signaling have revealed new insights on the development of RAS targeting strategies. Targeting upstream proteins, downstream proteins, and RAS directly, as well as RNA interference, represent the direct suppression of RAS oncogenic signals. Preclinical or clinical drugs that directly disturb RAS oncogenic signaling are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, RAS mutations bring specific characteristics, such as distinct metabolic processes and antigens, revealing indirect strategies that make targeting these characteristics feasible [63, 64]. Here, we summarize promising drugs with direct and indirect strategies in preclinical or clinical development (Tables 3 and 4).

Preclinical and clinical drugs targeting RAS-mutant tumors. (a) Targeting upstream molecules of RAS. Promising targets include PDEδ, SHP2, and STK19. (b) Targeting RAS directly, especially G12C covalent binders. (c) Targeting downstream RAF–MEK–ERK signaling. (d) Targeting downstream PI3K–AKT–mTOR signaling. (e) RNA interference of mutant RAS mRNA. Molecules that underwent clinical trials are indicated in green, those that are now under preclinical evaluation are indicated in lack. Napa, nanoparticle

Targeting upstream proteins

RAS proteins shift to the membrane for their biological activity. As a result, the idea of disrupting RAS translocation to cell membrane was proposed, especially in confronting the difficult approach of direct targeting of RAS. The initial attempt was to drug farnesyltransferase (FTase), which modifies the CAAX motif of RAS by farnesyl moiety addition. However, FTase inhibitors (FTIs) exhibited disappointing results in clinical trials toward to pancreatic cancer, which mainly possess KRAS mutation [65–67], and subsequent research revealed KRAS and NRAS gained alternative modifications by geranylgeranyltransferases (GGTase) in cells treated with FTIs [68]. Noteworthily, tipifarnib, a FTase inhibitor, exhibited encouraging efficiency in cancer harboring HRAS mutation [69, 70]. Although simultaneous inactivation of FTase and GGTase exhibited tumorigenesis inhibition in mouse models [71, 72], the toxicity associated with GGTIs limited their utility, thus reducing the benefit of targeting KRAS through combined FTase and GGTase inhibition [73]. Remarkedly, a bioactive natural compound from antrodia camphorata, antroquinonol, suppressed the proliferation of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. The potential mechanism was the inhibition of RAS through inactivation of FTase and GGTase [74].

Recently, another target, phenyl-binding protein phosphodiesterase δ (PDEδ), has attracted attention. PDEδ facilitates RAS protein transport to either the endosomes or the Golgi, from where RAS shifts to the plasma membrane. It was found to disrupt the interaction between KRAS–PDEδ to suppresses KRAS signaling, thus impairing the proliferation of PDAC cells in vitro and in vivo [75, 76]. The three molecules, NHTD, deltarasin, and deltazinone, competitively bind the prenyl-binding pocket of PDEδ, exhibiting the ability to impair the RAS protein stimulation at the membrane and further suppressing oncogenic KRAS signaling [77–79]. However, additional clinical study is required to test their toxicity and efficiency in patients.

In addition to interfering with the plasma localization of RAS proteins, targeting kinases or phosphatases that regulate RAS activity also represent an alternative option. Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11), also known as SHP2, is a mediator associated the stimulation of the downstream RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK pathway, promoting MAPK signal activation [80]. Although SHP099, an SHP2 inhibitor, displayed minimal anti-proliferation effects in KRAS or BRAF mutant cell lines in vitro, it shrank KRAS-mutant tumors in vivo [81, 82]. In addition, combined inhibition of MEK and SHP2 showed high efficiency in engineered or xenograft KRAS-mutant pancreas, ovarian, and lung cancer [81, 83–85], overcoming the rapid resistance to MEK inhibitor as a single therapy. Recently, the SHP2 inhibitor RMC-4630 exhibited an encouraging disease control rate (DCR) of 67% for advanced NSCLC patients harboring KRAS mutations [16]. The novel SHP2 inhibitors JAB-3068 and JAB-3312 are also under clinical investigation for safety and preliminary antitumor activity in KRAS-mutant solid tumors (NCT03565003 and NCT04045496, respectively).

The serine/threonine kinase STK19 was recently identified as another NRAS activator. STK19 phosphorylates NRAS protein at serine 89 and improved NRAS binding to its effectors. Consequently, STK19 inhibitor ZT-12-037-01 (1a) could inhibit oncogenic NRAS-mediated melanoma growth in vitro and in vivo [86]. Recently, we screened out a new pharmacological inhibitor of STK19 named chelidonine, which could suppress the growth of NRAS-mutant tumors in vitro and in vivo [87].

Direct targeting of RAS

Drugging RAS proteins directly used to be considered impossible. Although the guanine nucleotide (GN) binding site seems an ideal pocket, the sub-nanomolar affinity of GDP and GTP binding to RAS and their low intercellular concentrations make competitive nucleotide binding challenging. However, in recent years, targeting of RAS proteins directly has had a resurgence because of new findings in its crystal structure. The strategies include inhibiting the SOS–RAS interaction, trapping RAS in its inactive conformation, targeting the GN binding site, and hindering RAS effector interaction. Remarkedly, the KRASG12C inhibition acquired great breakthrough, especially with the recent approval of AMG510 for KRASG12C NSCLC patients, the history of undruggable target of RAS in the clinic ended.

First, inhibition of SOS-mediated nucleotide exchange activity was shown to make sense [88, 89]. DACI, a small molecule identified in a fragment screen, was found to bind the pocket of the RAS–SOS interaction surface. DACI restrained nucleotide exchange by blocking the interaction of RAS and SOS and inhibiting RAS activation in transformed cells [88]. Furthermore, another compound, BAY-293, selectively suppresses KRAS–SOS interaction with a proper IC50, is thus a promising compound for further investigation [90]. Remarkedly, another compound that disturbs RAS–SOS interactions, BI 1701963, is being evaluated for its efficiency alone or in combination with trametinib in solid tumors with KRAS mutation (NCT04111458).

Second, to suppress the activation of RAS, small molecules targeting inactive RAS proteins by a trapping mechanism is an alternative option [91]. ARS853 was identified as a selective inhibitor against the KRASG12C mutation by covalently reacting with RAS-GDP complex to trap it in its inactive state. ARS853 selectively inhibited downstream signaling and proliferation of cell lines harboring KRASG12C mutation [92]. Although ARS853 exhibited inhibitory effects in vitro, its poor stability in plasma (t1/2 < 20 min) makes further in vivo study challenging. Considering its potential clinical application, ARS1620 was designed to covalently and selectively react with GDP-bound RAS (RAS-GDP), displaying appropriate pharmacokinetics at the same time. ARS1620 exhibited selective tumor growth repression in a mouse tumor model [93]. Based on ARS1620, a novel-generation KRASG12C inhibitor, ARS3248 (JNJ-74699157) is undergoing clinical study of its safety and antitumor activity in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring KRASG12C mutation (NCT04006301). The biochemical mechanism of ARS853 and ARS1620 that possesses potent binding of mutant KRAS protein lies in KRAS-driven catalysis of the reaction between small molecules and Cys12 in the KRASG12C mutant [94, 95]. Despite ARS853 and ARS1620 suppressing RAS activation, limitations exist because most RAS proteins remain in the GTP-bound conformation. As a result, 2C07 was screened, which could bind in both a nucleotide state and still keep the trapping mechanism of G12C binders [96]. Another chemical probe, BI-2852, which is mechanistically diverse to covalent KRASG12C inhibitors, was designed to bind with the KRAS pocket with nanomolar affinity [97]. Surprisingly, an objective response has been observed in KRASG12C lung cancer or colorectal patients when treated with KRASG12C inhibitors AMG510 and MRTX849 [98, 99]. Regarding another common mutation, KRASG12D, MRTX1133 demonstrated clear tumor regression in KRASG12D positive preclinical cancer models, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma xenograft models [100].

Third, though targeting the GN binding site has been regarded as unfeasible, a GDP analogue, SML-8–73-1, can form covalent bonds with the GN site and prevent further nucleotide exchange, making targeting the GN site possible. Further, the compound stabilizes GDP-bound KRASG12C, whereas it is not easy to penetrate cells and has limited selectivity [101, 102]. Recently, a KRAS agonist, KRA-533, was identified to suppress mutant KRAS-driven lung cancer in vitro and in vivo, binding the GN binding site to prevent the exchange of GTP to GDP [103].

Fourth, disrupting the RAS effector interaction also represents a direction of RAS inhibition. Kobe0062 and Kobe0065 display inhibitory activity against HRAS and RAF interactions, and they suppress the growth of xenograft tumors harboring KRASG12C [104]. Moreover, rigosertib was proposed to inhibit RAS signaling as a RAS mimetic to competitively bind to RAS effectors and interfere with their ability to bind to RAS [94].

Considering the essentiality of normal RAS protein, mutant RAS proteins are the focus of drug development, which means the drugs usually target one or several subtypes of RAS mutations. However, a pan-RAS inhibitor, compound 3144, exhibited cellular lethality and tumor growth inhibition without any adverse effects. Compound 3144 was detected to bind to KRASG12D mutation, wild-type KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS at D38, A59, and Y32. This indicates that pan-RAS inhibitors may have antitumor efficiency and targeting multiple RAS mutations by one compound is feasible [105].

KRASG12C inhibitor AMG510

The identification of a cryptic pocket (H95/Y96/Q99) in KRASG12C enabled the emergence of AMG510, a selective and well-tolerated inhibitor. Its well-tolerability, excellent pharmacological profile and remarkable ability of KRASG12C tumor repression in vivo encouraged its further clinical study [106]. For the initial evaluable nine patients harboring KRASG12C-mutant cancer treated with AMG510, one patient had a partial response (PR) (NSCLC), six patients had stable disease (SD) (four CRC patients and two NSCLC patients), and two patients had progressive disease (PD) [107]. The additional follow-up in a larger group of patients (59 NSCLC, 42 CRC, 28 other) also exhibited encouraging results, with a 32.2% (19 patients) objective response rate (ORR) and an 88.1% (52 patients) DCR for NSCLC patients with KRASG12C mutation and a 7.1% (3 patients) ORR and a 73.8% (31 patients) disease control rate (DCR) for CRC patients [15]. The promising results in the subgroup of KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC patients encouraged the multi-center, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial (CodeBreaK100) of AMG510, administered orally at a dose of 960 mg once daily, in KRASG12C-mutant advanced NSCLC patients who had previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Among the 124 evaluated patients, there were 46 patients with objective response (37.1%), including in 4 patients (3.2%) with CR and in 42 patients (33.9%) with PR. The DCR was 80.6% in 100 patients. The median duration of response was 11.1 months. The median OS was 12.5 months, and the PFS was 6.8 months. What’s more, the clinical benefit of AMG510 was observed regardless of the mutation status of TP53, STK11 or KEAP1, PD-L1 expression level and tumor mutational burden [108]. Based-on the encouraging results of CodeBreaK100 clinical trial, with a 37.1% ORR and 58% of those patients had a duration of response of six months or longer, AMG510 were approved as the first treatment for KRASG12C mutant NSCLC patients who have received at least one prior systemic therapy. This approval ended the history of undruggable target of RAS in clinic [18]. The favorable antitumor efficiency of AMG510 promoted its combination with other targeted or cytotoxic agents and its combinations with MEKi, HERi, EGFRi, PI3Ki, AKTi, SHP2i, and PD-1i resulted in enhanced efficiency in vitro and in vivo [99]. A phase 3 clinical trial compared AMG510 with docetaxel in advanced KRASG12C mutant NSCLC patients is ongoing (NCT04303780, CodeBreaK200). Further, clinical investigation of AMG510 combined with other targeted agents is also under way (NCT04185883, CodeBreaK101). Notably, clinical acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibition has been observed, the mechanisms lie in multiple genomic or histologic mechanisms, in a study investigating mechanisms of the resistance to MRTX849 (adagrasib) monotherapy, in the 17 patients resistant to adagrasib monotherapy, KRAS alterations included G12D/R/V/W, G13D, Q61H, R68S, H95D/Q/R, Y96C, and high-level amplification of the KRAS(G12C) allele were observed, the bypass mechanisms including mutations in NRAS, BRAF, MAP2K1, and RET, loss-of-function mutations in NF1 and PTEN, fusions in ALK, RET, BRAF, RAF1, and FGFR3, histologic transformation [109]. The novel KRASY96D mutation affecting the switch-II pocket and polyclonal alterations converging on RAS-MAPK reactivation also represents mechanisms underlying clinical required resistance to KRASG12C inhibitors [110]. CRC patients possessing KRASG12C mutation exhibit limited efficiency regarding G12C inhibitors, EGFR signaling was identified as the dominant mechanism of resistance [111]. Novel strategies should be applied to overcome this drug resistance.

Targeting mutant RAS mRNA

Small interfering RNAs (siRNA) have great clinical potential because of their precise regulation of gene expression. However, the challenge exists in the effective delivery of RNAs to solid tumors. Recently, RNA interference targeting RAS has emerged. Systemic delivery of RAS-targeted RNAs by nanoparticles, nanoliposomes, or exosomes exhibits anti-proliferative effects in cells and in mouse tumor suppression [112–115]. For example, novel hybrid nanoparticles composed of mutant KRAS siRNA, IgG, and poloxamer-188 escaped the clearance of macrophage and delivered the siRNA to cells effectively [114]. Exosomes are essential mediators of cellular communication and have been explored in drug delivery systems because of their endogenous origin [116]. Compared with foreign nanoparticles or liposomes, exosomes do not induce an immune response and avoid clearance by macrophages. Recently, exosomes engineered to load siRNA specific to KRASG12D successfully inhibited tumors in mouse models of pancreatic cancer and prolonged OS, and further study revealed that CD47 on the surface of exosomes protected them from phagocytosis by monocytes. The relatively higher accumulation of exosomes in tumor tissues is generated by the increased micropinocytosis of tumor cells, which indirectly increases the specificity of exosomes [115]. Chemically modified antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) is also an alternative option for RAS targeting. A 2’-4’ constrained ethyl (cEt)-modified molecule, AZD4785, has good potency with high delivery efficiency and potent KRAS knockdown in tumor tissues. Furthermore, because the distribution of AZD4785 does not need any delivery formulation, immune response or clearance is avoided [117]. As a genome-editing system, CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully utilized to target the oncogenic KRASG12S-mutant allele and induce tumor regression [118].

In addition to the systemic delivery of siRNA, logical siRNA delivery systems represent a strategy. For example, local drug eluteR (LODER) can shed siRNA to peripheral tumor tissue consistently for more than 70 days. As a result, LODER containing KRASG12D-targeted siRNA can suppress the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells and improve the survival of mice [119]. Another clinical trial also demonstrated siG12D-LODER combination with chemotherapy to be a safe, effective approach for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer, with a median OS of 15.12 months. Though the number of enrolled patients was limited to only 15, it indicated that siG12D-LODER has clinical potential [120]. These studies suggest siRNA against mutant RAS mRNA represents a promising approach for RAS-targeting therapy.

Targeting downstream proteins

RAF inhibition

The challenge in developing novel drugs targeting RAS directly encourages a focus on the downstream effectors of RAS-driven cancer. The RAF kinases (ARAF, BRAF, and CRAF) constitute essential components in RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK signaling [121]. BRAF inhibitors dabrafenib and vemurafenib evoked notable responses and prolonged the survival of patients with BRAFV600E melanoma by disturbing the enhanced MAPK signaling [122]. However, in KRAS-mutant and RAF wild-type tumors, dabrafenib and vemurafenib activated the MAPK pathway instead of suppressing signaling [123, 124]. The underlying mechanism of this paradoxical activation lies in the activation of CRAF; these BRAF inhibitors drive RAS-dependent BRAF binding to CRAF, initiating the downstream signaling driven by CRAF [125]. Studies implicate that CRAF is vital for mutant KRAS signal transduction and tumor initiation other than BRAF [126]. Recent research found that CRAF-ablated tumors shrank with evidence of apoptosis, whereas there was no reduction in MAPK signaling in tumor tissues [127].

Combined inhibition of EGFR and CRAF also effectively suppresses the growth of patient-derived xenograft models with KRAS mutation [128]. A preclinical study also demonstrated that pan-RAF inhibitors RAF709 or LY3009120 exhibited antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo [129, 130]. Recently, a phase I clinical study of lifirafenib (BGB-283), a RAF family kinase inhibitor, showed patients with KRAS-mutated endometrial cancer and NSCLC had a confirmed PR (n = 1 each), while no response was observed in patients with KRAS- or NRAS-mutated colorectal cancer (n = 20) [131]. This evidence suggests that CRAF is a rational drug target and that pan-RAF inhibitors have the potential for RAS-mutant tumors.

MEK inhibition

The MEK inhibitor trametinib exhibits improved PFS and OS among patients who had metastatic melanoma with BRAFV600E or BRAFV600K mutation [132], indicating that MEK inhibition may represent an alternative strategy of halting the preternatural MAPK signaling in tumor. Furthermore, regarding NRAS-mutant melanoma patients, MEK inhibitors show activity [133, 134]. In a phase II study, six of 30 NRAS-mutant patients showed a PR to MEK162, a small molecule MEK inhibitor [133], and binimetinib improved the PFS of NRAS-mutant patients compared with dacarbazine (2.8 months vs 1.5 months, P < 0.001) [134]. However, a series of clinical studies showed no significance for MEK inhibition regarding KRAS-mutant tumors [135–138]. The underlying mechanism of this resistance was considered to be the reactivation of MEK. MEK inhibition is thought to relieve the feedback suppression of upstream signaling. Furthermore, CRAF mediates the reactivation of MAPK signaling [139, 140]. Thus, the notion of co-targeting MEK and CRAF or pan-RAF emerged; additionally, the combination strategy exhibited better anti-proliferation of cancer cells harboring KRAS mutations compared with MEK inhibitors alone [139, 140]. In a phase II clinical trial, combination of the MEK inhibitor refametinib plus sorafenib, both multiple kinase inhibitors that inhibit CRAF, showed antitumor activity in HCC patients, especially those with KRAS mutations [141]. The dual MEK/RAF inhibitor RO5126766(VS-6766) exhibited antitumor activity in participants harboring RAS mutations; one patient with an NRAS mutation obtained a PR [142]. The subsequent evaluation of RO5126766 in solid tumors or multiple myeloma (12 NSCLC, five gynecological malignancy, four colorectal cancer, one melanoma, and seven multiple myeloma) with RAS–RAF–MEK pathway mutations showed that 7 of 26 evaluable patients achieved objective responses [143]. Remarkedly, the combination of VS-6766 with defactinib obtained 70% ORR (7 of 10 evaluable patients) in LGSOC patients harboring KRAS mutation [17]. Further clinical studies of VS-6766 for KRAS-mutant NSCLC patients are ongoing (NCT03681483 and NCT03875820).

Because of the absence of paradoxical activation and the resistance to single MEK inhibitors for RAS-mutant tumors, MEK inhibitors are considered candidates for combination in RAS-mutant tumors and have exhibited feasible antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo [144–150]. For example, co-targeting of anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-XL or MCL-1 and MEK promotes tumor regression in KRAS-mutant tumor models compared with MEK targeting alone [144, 145]. Serine threonine phosphatase PP2A inhibition could confer MEK inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells [148]. Moreover, combined insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) and MEK blockade showed significant effects in KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells and in KRAS-driven mice tumor models [146]. Combined treatment with poly (adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and MEK inhibitors elicited synergistic effects in vitro and in vivo in multiple RAS mutant tumor models [150]. Remarkably, a phase II study of docetaxel and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) in NSCLC patients with KRAS mutation exhibited a 33% RR and a median survival of 11.1 months [151]. KRAS mutations may alter the expression of immune inhibitory molecules or immune cell infiltration, which indicates that MAPK signaling may have an impact on immune therapy [58, 59]. Combination of MEK inhibition and PD1/PD-L1 blockade prolonged OS of a KRAS-driven lung cancer model [152]. In addition, combining MEK inhibitors with agonist antibodies targeting the immunostimulatory CD40 receptor resulted in synergistic antitumor efficacy in KRAS-driven tumors [153].

ERK inhibition

The ERK inhibition strategy exhibits therapeutic potential against RAS-mutant, BRAF-mutant, BRAF- or MEK-inhibitor resistant tumors [154–156]. A novel molecule selectively targeting ERK, SCH772984, induced tumor regression in mouse xenograft models with KRAS or NRAS mutations [154]. AZD0364 exhibited dose- and time-dependent modulation of ERK1/2-dependent signaling to result in tumor regression in sensitive BRAF-and KRAS-mutant xenografts [157, 158]. Another similar small molecule, BVD523 (ulixertinib), exhibited antitumor activity for MEK–BRAF in concurrent or single targeting in resistant models in vitro or in vivo [156]. A clinical trial assessing BVD523 provided the first clinical evidence that ERK inhibitors were effective for patients with NRAS mutations, in which three of 18 NRAS-mutant patients responded to BVD523 [159]. As a result, ERK inhibition may represent a potential clinical weapon regarding RAS-mutant tumors [160].

PI3K–AKT–mTOR inhibition

The PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway represents another signaling pathway induced by RAS, it may serve as a complementary role for the RAF–MEK–ERK cascade [161]. As a result, co-targeting of the MAPK and PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathways was developed in preclinical trials. Typically, combination of PI3K and MEK inhibitors displayed synergistic effects in suppressing the proliferation of RAS-mutant cells and regressing xenografted RAS-mutant tumors [162–167]. For example, a dual pan-PI3K and mTOR inhibitor, NVP-BEZ235, was synthetic with MEK inhibitor in repressing KRASG12D mutant lung cancers [163]. Combination of MEK and PI3K/mTOR1,2 inhibition could induce apoptosis in NRAS mutant melanoma cancer cells and shrink tumor in mouse xenograft model [162]. The combination of KRASG12C inhibitor ARS1620 plus PI3K inhibitors was effective in vitro and in vivo including patient-derived xenografts models for NSCLC models with KRASG12C mutation [165].

With the rational combination strategy and validated pre-clinical efficiency. However, in clinical trials, the combination of PI3K and MEK inhibitors exhibited poorly tolerated toxicities or limited efficiency, which limited their utility in the clinic [168–173]. For example, there was no response in 23 RAS-mutant acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving combined MEK and AKT inhibition [174]. In 57 patients with solid tumors harboring RAS/RAF/PI3K mutations, the combination of GSK2126458, a pan-PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, with MEK inhibitor exhibited limited efficiency. The skin and gastrointestinal toxicities were poorly tolerated [168]. Similarly, 89 patients with RAS/RAF mutations were enrolled to study the efficiency and safety of MEK inhibitor binimetinib plus PI3K inhibitor buparlisib, only 6 patients achieved partial response and 32/89 patients suspended treatment due to the serious adverse events [173]. In addition, as a result, further investigations of the proper dosing schedule or more selective inhibitors are needed.

Similarly, mTOR inhibitor or its combination with other targets inhibitors, such as HDAC, BCL-2/BCL-XL, WEE1, KRAS, and MEK, exhibited inhibitory effects for RAS-driven tumors in vitro and in vivo [175–179]. For example, combined mTOR and HDAC inhibitors resulted in tumor regression in a mice xenografts models of KRAS-mutant NSCLC in vivo [178]. WEE1 and mTOR inhibitor induced efficient apoptosis in KRAS-mutant NSCLC cell lines and suppressed tumor growth in mice model [177]. A mTOR inhibitor, AZD8055 with a BCL-2 inhibitor exhibited synergistic cytotoxic effects in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer cells [176]. However, the mTOR inhibitors exhibited limited efficiency against cancers harboring RAS mutation in clinical trials [180–185]. For instance, the phase II study of evaluating the efficiency of Everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor in metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma previously treated with chemotherapy, among the 100 patients receiving daily everolimus, those with KRAS mutation (41 patients) owned shorter OS (5.59 months vs 7.06 months) and lower DCR (7% vs 14%) compared with those with wild KRAS [181]. Similarly, in a cohort of cancer patients receiving everolimus, only 1/12 patients with KRAS mutation had disease control, while 15/31 wild cases benefited from the treatment [186].

Remarkedly, the combination of MEK and AKT inhibitors obtained antitumor ability in certain KRAS-driven human cancers, in a cohort of patients with solid tumors receiving MEK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib and allosteric AKT inhibitors MK-2206, 3 of 13(23%) NSCLC patients and 1 of 2(50%) OVCA patients with KRAS mutation obtained PR, while there was no objective response in colorectal cancers with KRAS mutations [167]. In RAS-mutant AML, combined MEK and AKT inhibition had no clinical efficiency in 23 patients with RAS mutation [174]. Further investigations of the combination of MEK and AKT inhibitors in clinic are needed.

Targeting metabolic processes affected by RAS mutations

It is essential for tumors to reprogram the metabolic processes in support of the elevated proliferation state. Oncogenic RAS-driven cancer cells are known to refer to elevated macro-pinocytosis and macro-autophagy. Furthermore, increased glucose metabolism and dependency on glutamine are also hallmarks for RAS-mutant tumors [161]. In PDAC, autophagy plays a critical role for tumor growth and progression [187, 188]. It was found that MAPK signaling and autophagy pathways cooperate to promote RAS-mutant cell survival [189]. Thus, the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine was combined with the ERK inhibitor SCH772984, resulting in elevated antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo in PDAC [190]. Furthermore, combined inhibition of MEK plus autophagy showed synergistic antitumor activity against patient-derived xenografts of KRAS-mutant PDAC and NRAS-mutant melanoma [191]. These data suggest the strategies of combining autophagy blockade and MAPK inhibition may represent new avenues for targeting RAS-mutant tumors.

Other strategies of targeting mutant RAS

PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) has emerged a novel and promising strategy to eliminate a protein of interest (POI). Bifunctional molecules combine POI with an E3 ligase, forming a ternary complex, enabling E3 ligase to ubiquitinate the POI and subsequently the POI is recognized and degraded [192, 193]. Recently, a bifunctional molecule, LC-2, was reported to covalently binds KRASG12C with a MRTX849 bridge and recruits E3 ligase. Subsequently, the KRASG12C protein was ubiquitinated and degraded persistently, the MAPK signaling was suppressed in cancer cells [194]. Similarly, PROTACs incorporating ARS-1620 and E3 ligase through a thalidomide scaffold could degraded GFP-KRASG12C in reporter cells [195]. PROTACs represent a novel direction in small-molecule-mediated targeting and degradation of RAS. However, it depends on the development of bifunctional molecular binding to target protein directly. Therefore, tag-based PROTACs have been developed, which utilizes the CRISPR/Cas-mediated locus-specific knock-in or transgene expression to form the fusion of tag protein and POI, small molecules subsequently induce the degradation of tag fusion protein [192]. The tag-based PROTACs mainly contain the haloPROTACs system and the dTAG system [196]. In the haloPROTACs system, the administration of HyT13 successfully degraded haloTag–HRASG12V fusion protein in NIH-3T3 cells and suppressed the tumor formation in mice [197]. Similarly, the dTAG system, which relies on the fusion of FKBP12F36V to the terminus of POI, effectively degraded FKBP12F36V-tagged KRASG12V and decreased the downstream signaling in cells [198]. What’s more, taking advantage of haloPROTACs, a ligand-inducible tractable affinity-directed protein missile system (L-AdPROM), in which aHRAS conjugated to the Halo-tag and tagged with a FLAG reporter, successfully degraded RAS and reduce the RAS-driven signaling in A549 cells [199]. In addition, PROTACs regarding some targets in RAS signaling pathway, such as MEK, PDEδ, TBK1 and SHP2, also successfully degraded the corresponding targets and suppressed the RAS signaling in vitro or in vivo [200–203].

Mutant RAS may generate abnormal proteins that can evoke the immune response, suggesting the feasibility of immunotherapy utilization in RAS-mutant cancer. One study noted the shrinkage of all lung metastases (seven in total) after the transfer of KRASG12D-specific CD8 + T cells in a mCRC patient, which indicated immunotherapy may have potential in targeting mutant KRAS [204]. Several clinical studies are ongoing to evaluate the efficiency and safety of immunotherapy targeting mutant RAS. For example, peripheral blood lymphocytes with modified mTCR that target KRASG12D and KRASG12V are under clinic investigation for rectal and pancreatic cancer (NCT03745326 and NCT03190941, respectively). In addition, a mRNA-based cancer vaccine (V941) targeting the most commonly occurring KRAS mutations (G12D, G12V, and G12C) is under clinical study (NCT03948763).

Another strategy targeting mutant RAS is screening for synthetic lethal interactors, which aims to identify genes that are vital to RAS-mutant but not wild-type cells. The progress of synthetic lethal interactors for mutant RAS is reviewed elsewhere [14].

Conclusion

Great progress has been made in the past few years, especially with the approval of Lumakras (sotorasib, AMG510) in treatment of KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC patients who have received at least one prior systemic therapy, this approval ended the history of no drug in clinic for RAS mutation. However, there are limited patients who can benefit from it, with only about 13% of KRASG12C mutation in NSCLC patients, CRC patients with KRASG12C mutation obtained low clinical response [18]. Thus, further investigation of strategies targeting mutant RAS is necessary. One potential direction is the combination of several inhibitors. These combination strategies are designed to avoid reactivating the MAPK pathway, among which, MEK inhibitors represent the most favorable candidate for combination because of the absence of paradoxical activation and the existence of approved MEK inhibitors. Apart from combining molecules in the MAPK or PI3K–AKT cascades with MEK inhibitors, screening genes that sensitize MEK inhibitors based on short-hairpin RNA or CRISPR may also identify potential combinable candidates [145, 147, 205]. MRTX 849, RMC-4630 and VS-6766 had early encouraging outcomes, demonstrating antitumor activity in patients harboring KRAS mutation (MRTX 849 for KRASG12C) [16, 98, 99, 143]. However, the efficacy and safety still need to be confirmed through large samples and multi-center phase III clinical studies before clinical application. RNA interference represents a promising approach to suppress the expression of mutant RAS, but clinical studies are needed to evaluate their efficiency and safety. The issues of targeting RAS are still ongoing, and we must recognize that a simple therapy will not be effective for all RAS-mutant cancers. Consequently, multiple RAS-targeting strategies are needed for RAS-mutant subsets. Targeting mutant RAS remains a potentially effective treatment in the future.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- aBTC:

-

Advanced biliary tract cancer

- AJCC:

-

American joint committee on cancer

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- aPC:

-

Advanced pancreatic cancer

- ASO:

-

Antisense oligonucleotide

- anti-EGFR:

-

Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor

- BSC:

-

Best supportive care

- Cap:

-

Capecitabine

- CC:

-

Colon cancer

- CMML:

-

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

- CP:

-

Carboplatin and paclitaxel

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CTLA-4:

-

Cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen 4

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- EC:

-

Endometrial cancer

- EOC:

-

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- ESC:

-

Esophageal carcinoma

- FOLFIRI:

-

5-Fluorouracil, folinic acid, and irinotecan

- FOLFOX4:

-

Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin

- FTIs:

-

FTase inhibitors

- FU/LV:

-

5FU + leucovorin

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- Gem:

-

Gemcitabine

- GICA:

-

Gastrointestinal cancer

- GGTase:

-

Geranylgeranyltransferases

- GN:

-

Guanine nucleotide

- HVRs:

-

Hypervariable regions

- ICB:

-

Immune checkpoint blockade

- IFL:

-

Fluorouracil [5-FU], leucovorin, and irinotecan

- IGF1R:

-

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- IMA:

-

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung

- KMP:

-

KRAS-mutant patients

- KWP:

-

Wild-type KRAS patients

- LAPC:

-

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer

- lnc:

-

Include, means including patients with RAS mutation

- LODER:

-

Local drug eluteR

- LUAC:

-

Lung adenocarcinoma

- mCRC:

-

Metastatic colorectal cancer

- MM:

-

Malignant melanoma

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- Mut:

-

Mutation

- NA:

-

None

- Napa:

-

Nanoparticle

- ND:

-

Not determined

- NF1:

-

Neurofibromatosis type 1

- NM:

-

Not mentioned

- NMP:

-

NRAS-mutant patients

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung carcinoma;

- OEC:

-

Ovarian epithelial cancer

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- OVCA:

-

Ovarian cancer

- Ox:

-

Oxaliplatin

- PanIN:

-

Pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia

- PanNEN-G3:

-

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm grade-3

- PBL:

-

Peripheral blood lymphocytes

- PC:

-

Pancreatic cancer

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PD1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma

- PDEδ:

-

Phenyl-binding protein phosphodiesterase δ

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- PTPN11:

-

Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11

- RalGEFs:

-

Ral guanine exchange factors

- RC:

-

Rectal cancer

- RFS:

-

Recurrence-free survival

- RNAi:

-

RNA interference

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- SIA:

-

Small intestinal adenocarcinoma

- SHP2:

-

SRC homology-2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2

- TIL:

-

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

References

Parada LF, Tabin CJ, Shih C, et al. Human EJ bladder carcinoma oncogene is homologue of Harvey sarcoma virus ras gene. Nature. 1982;297(5866):474–8.

Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–65.

Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80(14):2969–74.

Guerrero S, Casanova I, Farre L, et al. K-ras codon 12 mutation induces higher level of resistance to apoptosis and predisposition to anchorage-independent growth than codon 13 mutation or proto-oncogene overexpression. Cancer Res. 2000;60(23):6750–6.

Khan AQ, Kuttikrishnan S, Siveen KS, et al. RAS-mediated oncogenic signaling pathways in human malignancies. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2019;54:1–13.

Jakob JA, Bassett RL Jr, Ng CS, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118(16):4014–23.

Foltran L, de Maglio G, Pella N, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in advanced colorectal cancer. Future Oncol. 2015;11(4):629–40.

Devitt B, Liu W, Salemi R, et al. Clinical outcome and pathological features associated with NRAS mutation in cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24(4):666–72.

Ellerhorst JA, Greene VR, Ekmekcioglu S, et al. Clinical correlates of NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary human melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;17(2):229–35.

Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):2091–6.

Lievre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):374–9.

van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Kohne CH, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):692–700.

Kurzrock R, Ball DW, Zahurak ML, et al. A phase I trial of the VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib in combination with the MEK inhibitor trametinib in advanced solid tumors and differentiated thyroid cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(18):5475–84.

Downward J. RAS synthetic lethal screens revisited: still seeking the elusive prize? Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(8):1802–9.

Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, et al. KRAS(G12C) inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1207–17.

Sai-Hong I, Ou MK, Susanna V, Ulahannan, et al. The SHP2 inhibitor RMC-4630 in patients with KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: preliminary evaluation of a first-in-man phase 1 clinical trial. J Thoracic Oncol. 2020;15(2):S15–S16.

Verastem Oncology Receives Breakthrough Therapy Designation for VS-6766 with Defactinib in Recurrent Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer | Verastem Inc [EB/OL].[2021-05-24]. https://investor.verastem.com/news-releases/news-release-details/verastem-oncology-receives-breakthrough-therapy-designation-vs.

FDA Approves First Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Mutation Previously Considered Resistant to Drug Therapy.[EB/OL].[2021-05-28]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-targeted-therapy-lung-cancer-mutation-previously-considered-resistant-drug.

Ferdinandos Skoulidis BTL, Govindan R, Dy GK, Shapiro G, Bauml J, Schuler MH, Addeo A, Kato T, Besse B, Abrahamanderson AA, Ngarmchamnanrith G, Tran Q, Vamsidharvelcheti. Overall survival and exploratory subgroup analyses from the phase 2 CodeBreaK 100 trial evaluating sotorasib in pretreated KRAS p.G12C mutated non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 39, (suppl 15; abstr 9003) (2021).

Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science (New York, NY). 2001;294(5545):1299–304.

Schopel M, Potheraveedu VN, Al-Harthy T, et al. The small GTPases Ras and Rheb studied by multidimensional NMR spectroscopy: structure and function. Biol Chem. 2017;398(5–6):577–88.

Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):269–309.

Roskoski R Jr. RAF protein-serine/threonine kinases: structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399(3):313–7.

Krygowska AA, Castellano E. PI3K: a crucial piece in the RAS signaling puzzle. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. 2018;8(6):a031450.

Hofer F, Fields S, Schneider C, et al. Activated Ras interacts with the Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(23):11089–93.

Pacold ME, Suire S, Perisic O, et al. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell. 2000;103(6):931–43.

Fetics SK, Guterres H, Kearney BM, et al. Allosteric effects of the oncogenic RasQ61L mutant on Raf-RBD. Structure (London, England: 1993). 2015;23(3):505–16.

Xu S, Long BN, Boris GH, et al. Structural insight into the rearrangement of the switch I region in GTP-bound G12A K-Ras. Acta crystallographica Sect D Struct Biol. 2017;73(Pt 12):970–84.

Lu S, Banerjee A, Jang H, et al. GTP binding and oncogenic mutations may attenuate hypervariable region (HVR)-catalytic domain interactions in small GTPase K-Ras4B, exposing the effector binding site. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(48):28887–900.

Burd CE, Liu W, Huynh MV, et al. Mutation-specific RAS oncogenicity explains NRAS codon 61 selection in melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(12):1418–29.

Garcia-Rostan G, Zhao H, Camp RL, et al. ras mutations are associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor prognosis in thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3226–35.

Guo TA, Wu YC, Tan C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic value of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations and DNA mismatch repair status: a single-center retrospective study of 1,834 Chinese patients with Stage I-IV colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(6):1625–34.

Yaeger R, Cowell E, Chou JF, et al. RAS mutations affect pattern of metastatic spread and increase propensity for brain metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1195–203.

Tie J, Lipton L, Desai J, et al. KRAS mutation is associated with lung metastasis in patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(5):1122–30.

Sasaki K, Margonis GA, Wilson A, et al. Prognostic implication of KRAS status after hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases varies according to primary colorectal tumor location. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(11):3736–43.

Margonis GA, Spolverato G, Kim Y, et al. Effect of KRAS mutation on long-term outcomes of patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(13):4158–65.

Karagkounis G, Torbenson MS, Daniel HD, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAF mutation in patients undergoing liver surgery for colorectal metastases. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4137–44.

Denbo JW, Yamashita S, Passot G, et al. RAS mutation is associated with decreased survival in patients undergoing repeat hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(1):68–77.

Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Association between NRAS and BRAF mutational status and melanoma-specific survival among patients with higher-risk primary melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(3):359–68.

Nodin B, Zendehrokh N, Sundstrom M, et al. Clinicopathological correlates and prognostic significance of KRAS mutation status in a pooled prospective cohort of epithelial ovarian cancer. Diagnostic Pathol. 2013;8:106.

Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):1023–34.

Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M, et al. Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(29):3570–7.

Tural D, Selcukbiricik F, Erdamar S, et al. Association KRAS G13D tumor mutated outcome in patients with chemotherapy refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1035–40.

Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5900–9.

Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(10):2890–6.

Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE, Der CJ, et al. Personalized medicine in non-small-cell lung cancer: is KRAS a useful marker in selecting patients for epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4769–77.

Zer A, Ding K, Lee SM, et al. Pooled analysis of the prognostic and predictive value of KRAS mutation status and mutation subtype in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(3):312–23.

Brugger W, Triller N, Blasinska-Morawiec M, et al. Prospective molecular marker analyses of EGFR and KRAS from a randomized, placebo-controlled study of erlotinib maintenance therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):4113–20.

Mao C, Qiu LX, Liao RY, et al. KRAS mutations and resistance to EGFR-TKIs treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of 22 studies. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2010;69(3):272–8.

Taieb J, Zaanan A, Le Malicot K, et al. Prognostic effect of BRAF and KRAS mutations in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab: a post hoc analysis of the PETACC-8 trial. JAMA Oncol 2016;2(5):643–653.

Yoon HH, Tougeron D, Shi Q, et al. KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in relation to disease-free survival in BRAF-wild-type stage III colon cancers from an adjuvant chemotherapy trial (N0147 alliance). Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(11):3033–43.

Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60–00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):466–74.

Blons H, Emile JF, le Malicot K, et al. Prognostic value of KRAS mutations in stage III colon cancer: post hoc analysis of the PETACC8 phase III trial dataset. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(12):2378–85.

Lin YL, Liang YH, Tsai JH, et al. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy is more beneficial in KRAS mutant than in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e86789.

Lin YL, Liau JY, Yu SC, et al. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy might provide longer progression-free survival in KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(3):363–9.

Hijioka S, Hosoda W, Matsuo K, et al. Rb loss and KRAS mutation are predictors of the response to platinum-based chemotherapy in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with grade 3: a Japanese Multicenter Pancreatic NEN-G3 Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(16):4625–32.

Sanmamed MF, Chen L. A paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy: from enhancement to normalization. Cell. 2018;175(2):313–26.

Lococo F, Torricelli F, Rossi G, et al. Inter-relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinic-pathological features and driver gene mutations in pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;113:93–101.

Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Bandlamudi C, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinomas. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(5):599–608.

Jeanson A, Tomasini P, Souquet-Bressand M, et al. Brief report: efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in KRAS-mutant Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1095–1101.

Liao W, Overman MJ, Boutin AT, et al. KRAS-IRF2 axis drives immune suppression and immune therapy resistance in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(4):559–72.e7.

Lal N, White BS, Goussous G, et al. KRAS mutation and consensus molecular subtypes 2 and 3 are independently associated with reduced immune infiltration and reactivity in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(1):224–33.

Kerr EM, Gaude E, Turrell FK, et al. Mutant Kras copy number defines metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic susceptibilities. Nature. 2016;531(7592):110–3.

Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. 2013;496(7443):101–5.

Macdonald JS, McCoy S, Whitehead RP, et al. A phase II study of farnesyl transferase inhibitor R115777 in pancreatic cancer: a Southwest oncology group (SWOG 9924) study. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23(5):485–7.

van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1430–8.

Yam C, Murthy RK, Valero V, et al. A phase II study of tipifarnib and gemcitabine in metastatic breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2018;36(2):299–306.

Whyte DB, Kirschmeier P, Hockenberry TN, et al. K- and N-Ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein transferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(22):14459–64.

Ho AL, Brana I, Haddad R, et al. Tipifarnib in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with HRAS mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;Jco2002903.

Lee HW, Sa JK, Gualberto A, et al. A phase II trial of tipifarnib for patients with previously treated, metastatic urothelial carcinoma harboring HRAS mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(19):5113–9.

Liu M, Sjogren AK, Karlsson C, et al. Targeting the protein prenyltransferases efficiently reduces tumor development in mice with K-RAS-induced lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(14):6471–6.

Kazi A, Xiang S, Yang H, et al. Dual farnesyl and geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor thwarts mutant KRAS-driven patient-derived pancreatic tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5984–96.

Lobell RB, Omer CA, Abrams MT, et al. Evaluation of farnesyl:protein transferase and geranylgeranyl:protein transferase inhibitor combinations in preclinical models [J]. Cancer Res. 2001;61(24):8758–68.

Ho CL, Wang JL, Lee CC, et al. Antroquinonol blocks Ras and Rho signaling via the inhibition of protein isoprenyltransferase activity in cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2014;68(8):1007–14.

Zimmermann G, Papke B, Ismail S, et al. Small molecule inhibition of the KRAS-PDEdelta interaction impairs oncogenic KRAS signalling. Nature. 2013;497(7451):638–42.

The KRAS-PDEdelta interaction is a therapeutic target. Cancer Discov 2013;3(7):Of20.

Papke B, Murarka S, Vogel HA, et al. Identification of pyrazolopyridazinones as PDEdelta inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11360.

Frett B, Wang Y, Li HY. Targeting the K-Ras/PDEdelta protein-protein interaction: the solution for Ras-driven cancers or just another therapeutic mirage? ChemMedChem. 2013;8(10):1620–2.

Leung EL, Luo LX, Li Y, et al. Identification of a new inhibitor of KRAS-PDEδ interaction targeting KRAS mutant nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(5):1334–45.

Dance M, Montagner A, Salles JP, et al. The molecular functions of Shp2 in the Ras/Mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2) pathway. Cell Signal. 2008;20(3):453–9.

Mainardi S, Mulero-Sanchez A, Prahallad A, et al. SHP2 is required for growth of KRAS-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer in vivo. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):961–7.

Chen YN, Lamarche MJ, Chan HM, et al. Allosteric inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase inhibits cancers driven by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature. 2016;535(7610):148–52.

Wong GS, Zhou J, Liu JB, et al. Targeting wild-type KRAS-amplified gastroesophageal cancer through combined MEK and SHP2 inhibition. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):968–77.

Fedele C, Ran H, Diskin B, et al. SHP2 Inhibition prevents adaptive resistance to MEK inhibitors in multiple cancer models. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(10):1237–49.

Lu H, Liu C, Velazquez R, et al. SHP2 inhibition overcomes RTK-mediated pathway reactivation in KRAS-mutant tumors treated with MEK inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(7):1323–34.

Yin C, Zhu B, ZHANG T, et al. Pharmacological Targeting of STK19 Inhibits Oncogenic NRAS-Driven Melanomagenesis [J]. Cell. 2019;176(5):1113–27.e16.

Qian L, Chen K, Wang C, et al. Targeting NRAS-Mutant cancers with the selective STK19 kinase inhibitor chelidonine [J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(13):3408–19.

Maurer T, Garrenton LS, Oh A, et al. Small-molecule ligands bind to a distinct pocket in Ras and inhibit SOS-mediated nucleotide exchange activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(14):5299–304.

Sun Q, Burke JP, Phan J, et al. Discovery of small molecules that bind to K-Ras and inhibit Sos-mediated activation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(25):6140–3.

Hillig RC, Sautier B, Schroeder J, et al. Discovery of potent SOS1 inhibitors that block RAS activation via disruption of the RAS-SOS1 interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(7):2551–60.

Lito P, Solomon M, Li LS, et al. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. 1095–9203 (Electronic)).

Patricelli MP, Janes MR, Li LS, et al. Selective inhibition of oncogenic KRAS output with small molecules targeting the inactive state. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(3):316–29.

Janes MR, Zhang J, Li LS, et al. Targeting KRAS mutant cancers with a covalent G12C-specific inhibitor. Cell. 2018;172(3):578-89.e17.

Athuluri-Divakar SK, Vasquez-Del-Carpio R, Dutta K, et al. A small molecule RAS-mimetic disrupts RAS association with effector proteins to block signaling. Cell. 2016;165(3):643–55.

Hansen R, Peters U, Babbar A, et al. The reactivity-driven biochemical mechanism of covalent KRAS(G12C) inhibitors. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25(6):454–62.

Gentile DR, Rathinaswamy MK, Jenkins ML, et al. Ras binder induces a modified switch-II pocket in GTP and GDP states. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24(12):1455-66.e14.

Kessler D, Gmachl M, Mantoulidis A, et al. Drugging an undruggable pocket on KRAS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(32):15823–9.

Hallin J, Engstrom LD, Hargis L, et al. The KRAS(G12C) inhibitor MRTX849 provides insight toward therapeutic susceptibility of KRAS-mutant cancers in mouse models and patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(1):54–71.

Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575(7781):217–23.

<MRTX-Corporate-Presentation-Update_6Aug2020_website_PDF.pdf>.

Lim SM, Westover KD, Ficarro SB, et al. Therapeutic targeting of oncogenic K-Ras by a covalent catalytic site inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(1):199–204.

Hunter JC, Gurbani D, Ficarro SB, et al. In situ selectivity profiling and crystal structure of SML-8-73-1, an active site inhibitor of oncogenic K-Ras G12C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(24):8895–900.

Xu K, Park D, Magis AT, et al. Small molecule KRAS agonist for mutant KRAS cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):85.

Shima F, Yoshikawa Y, Ye M, Araki M, et al. In silico discovery of small-molecule Ras inhibitors that display antitumor activity by blocking the Ras-effector interaction. 1091–6490 (Electronic)).

Welsch ME, Kaplan A, Chambers JM, et al. Multivalent small-molecule pan-RAS inhibitors. Cell. 2017;168(5):878-89.e29.

Lanman BA, Allen JR, Allen JG, et al. Discovery of a covalent inhibitor of KRAS(G12C) (AMG 510) for the treatment of solid tumors. J Med Chem. 2020;63(1):52–65.

Fakih M, O’Neil B, Price TJ, et al. Phase 1 study evaluating the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), and efficacy of AMG 510, a novel small molecule KRASG12C inhibitor, in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):3003.

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371–81.

Awad MM, Liu S, Rybkin II, et al. Acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2382–93.

Tanaka N, Lin JJ, Li C, et al. Clinical acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibition through a novel KRAS switch-II pocket mutation and polyclonal alterations converging on RAS-MAPK reactivation. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1–10.

Amodio V, Yaeger R, Arcella P, et al. EGFR Blockade Reverts Resistance to KRAS(G12C) Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer [J]. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(8):1129–39.

Xue W, Dahlman JE, Tammela T, et al. Small RNA combination therapy for lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(34):E3553–61.

Pecot CV, Wu SY, Bellister S, et al. Therapeutic silencing of KRAS using systemically delivered siRNAs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(12):2876–85.

Lakshmikuttyamma A, Sun Y, Lu B, et al. Stable and efficient transfection of siRNA for mutated KRAS silencing using novel hybrid nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(12):4415–24.

Kamerkar S, Lebleu VS, Sugimoto H, et al. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;546(7659):498–503.

Johnsen KB, Gudbergsson JM, Skov MN, et al. A comprehensive overview of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles—endogenous nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2014;1846(1):75–87.

Ross SJ, Revenko AS, Hanson LL, et al. Targeting KRAS-dependent tumors with AZD4785, a high-affinity therapeutic antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of KRAS. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(394):eaal5253.

Gao Q, Ouyang W, Kang B, et al. Selective targeting of the oncogenic KRAS G12S mutant allele by CRISPR/Cas9 induces efficient tumor regression. Theranostics. 2020;10(11):5137–53.

Zorde Khvalevsky E, Gabai R, Rachmut IH, et al. Mutant KRAS is a druggable target for pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(51):20723–8.

Golan T, Khvalevsky EZ, Hubert A, et al. RNAi therapy targeting KRAS in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):24560–70.

Karoulia Z, Gavathiotis E, Poulikakos PI. New perspectives for targeting RAF kinase in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(11):676–91.

Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–16.

Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464(7287):431–5.

Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, et al. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464(7287):427–30.

Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140(2):209–21.

McCormick F. c-Raf in KRas mutant cancers: a moving target. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(2):158–9.

Sanclemente M, Francoz S, Esteban-Burgos L, et al. c-RAF ablation induces regression of advanced Kras/Trp53 mutant lung adenocarcinomas by a mechanism independent of MAPK signaling. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(2):217-28.e4.

Blasco MT, Navas C, Martín-Serrano G, et al. Complete regression of advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas upon combined inhibition of EGFR and C-RAF. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(4):573–87.e6.

Peng SB, Henry JR, Kaufman MD, et al. Inhibition of RAF isoforms and active dimers by LY3009120 leads to anti-tumor activities in RAS or BRAF mutant cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(3):384–98.

Shao W, Mishina YM, Feng Y, et al. Antitumor properties of RAF709, a highly selective and potent inhibitor of RAF kinase dimers, in tumors driven by mutant RAS or BRAF. Cancer Res. 2018;78(6):1537–48.

Desai J, Gan H, Barrow C, et al. Phase I, open-label, dose-escalation/dose-expansion study of lifirafenib (BGB-283), an RAF family kinase inhibitor, in patients with solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;Jco1902654.

Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107–14.

Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, et al. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):249–56.

Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Ascierto PA, et al. Binimetinib versus dacarbazine in patients with advanced NRAS -mutant melanoma (NEMO): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(4):435–45.

Janne PA, van den Heuvel MM, Barlesi F, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel compared with docetaxel alone and progression-free survival in patients with KRAS-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the SELECT-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1844–53.

Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Franklin W, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2139–46.

Blumenschein GR Jr, Smit EF, Planchard D, et al. A randomized phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) compared with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)dagger. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):894–901.

Infante JR, Somer BG, Park JO, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of trametinib, an oral MEK inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine for patients with untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(12):2072–81.

Lito P, Saborowski A, Yue J, et al. Disruption of CRAF-mediated MEK activation is required for effective MEK inhibition in KRAS mutant tumors. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(5):697–710.

Yen I, Shanahan F, Merchant M, et al. Pharmacological induction of RAS-GTP confers RAF inhibitor sensitivity in KRAS mutant tumors. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(4):611-25.e7.

Lim HY, Heo J, Choi HJ, et al. A phase II study of the efficacy and safety of the combination therapy of the MEK inhibitor refametinib (BAY 86–9766) plus sorafenib for Asian patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):5976–85.

Martinez-Garcia M, Banerji U, Albanell J, et al. First-in-human, phase I dose-escalation study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of RO5126766, a first-in-class dual MEK/RAF inhibitor in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(17):4806–19.

Guo C, Chénard-Poirier M, Roda D, et al. Intermittent schedules of the oral RAF-MEK inhibitor CH5126766/VS-6766 in patients with RAS/RAF-mutant solid tumours and multiple myeloma: a single-centre, open-label, phase 1 dose-escalation and basket dose-expansion study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1478–88.

Nangia V, Siddiqui FM, Caenepeel S, et al. Exploiting MCL1 dependency with combination MEK + MCL1 inhibitors leads to induction of apoptosis and tumor regression in KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(12):1598–613.

Corcoran RB, Cheng KA, Hata AN, et al. Synthetic lethal interaction of combined BCL-XL and MEK inhibition promotes tumor regressions in KRAS mutant cancer models. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(1):121–8.