Abstract

Background

Ewing sarcoma (EWS) is a malignant tumour of bone and soft tissue, and although many patients are cured with conventional multimodal therapy, those with recurrent or metastatic disease have a poor prognosis. Genomic instability and programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression have been identified in EWS, providing a rationale for treatment with agents that block the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor.

Case presentation

In this report, we describe a heavily pre-treated patient with recurrent metastatic EWS who achieved a clinical and radiological remission with PD-1 blockade.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case demonstrating efficacy of PD-1 blockade in EWS. This warrants further investigation in particular given the poor prognosis in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

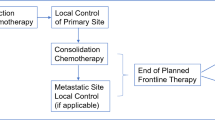

Ewing sarcoma (EWS) is a poorly differentiated, aggressive malignant small blue round cell tumour of the bone and soft tissue [1]. It accounts for 34 % of primary bone tumours in people <20 years with an incidence of 2.9 per million [2]. Conventional treatment for localised disease is induction multi-agent chemotherapy then local control with surgery and/or radiation therapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy [3]. Nevertheless, approximately 30–40 % of patients develop recurrent local or metastatic disease, which is associated with a poor prognosis and a 5-year survival of 10–25 % [4–6].

Immune therapy using agents that target the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor interaction via its ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2 has shown efficacy in patients with advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma and other malignancies [7–10]. In colorectal cancer, clinical response is correlated with mis-match repair (MMR) deficiency and microsatellite instability [8, 11]. Genomic instability has been described in EWS providing a rationale for treatment with immune checkpoint blockade [12, 13]. To our knowledge, the patient described here is the first to document the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in EWS.

Case presentation

Our patient is a 19-year-old male who presented in 2010 with left arm weakness secondary to a left C4-C6 paravertebral mass with bony involvement of C6 and T1. There were no additional sites of disease on a chest CT and a whole body 18F-FDG PET-CT scan. A CT-guided core biopsy showed a tumour composed of uniform small round cells with hyperchromatic round nuclei and scant cytoplasm (Fig. 1a). The neoplastic cells showed positive staining in immunostains for CD99 (membranous; Fig. 1b) and FLI-1 (nuclear) and were negative in immunostains for desmin, myogenin and S-100. Intracytoplasmic glycogen was demonstrated in a PAS stain. The combined morphological and immunophenotypic features were consistent with EWS (the presence of EWSR1 rearrangement was confirmed on a subsequent biopsy). The patient received chemotherapy (vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide/etoposide) and local intensity modulated radiation therapy (55Gy/25#) to his mid-cervical spine. At the end of treatment, there was no clinical or radiological evidence of residual or recurrent disease.

Fifteen months after diagnosis, surveillance imaging identified bony and pulmonary metastatic disease. Biopsy of a right humeral lesion was morphologically consistent with recurrent EWS and molecular testing for the EWSR1 rearrangement was positive. Over the next 4 years, he was treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens including irinotecan/temozolamide, high-dose ifosfamide, gemcitabine/docetaxel, a hedgehog signalling pathway inhibitor (LDE225) and carboplatin/etoposide. He had palliative radiotherapy to multiple bony sites including the right humerus, left ilium, thoracic and lumbar spine and bilateral whole lung radiation with additional stereotactic therapy to the largest pulmonary metastases. Over this period, there were short-lived responses and periods of stable disease but a clinical or radiological second remission was not achieved.

In May 2015, just over 5 years from diagnosis, restaging whole body 18F-FDG PET-CT demonstrated multiple pulmonary metastases and increased FDG uptake at T11, T12 and the left ischium (Fig. 2a). The peak standardised uptake value (SUV) in the T12 lesion was 14.0. Chest CT confirmed 43 nodules of varying sizes throughout both lung fields (Fig. 3a, c) and thoracolumbar spine MR imaging demonstrated bony metastatic disease at T12, L1, L2, L4 and L5 with associated soft tissue mass at T12/L1 (Fig. 4a, b). He complained of low back pain but was otherwise asymptomatic with ECOG performance score of 0.

Coronal 18F-FDG PET-CT scans done prior to (a) and after (b) 3 cycles of pembrolizumab. The markedly increased FDG uptake in the right side and adjacent soft tissues of T12, in the left ischium and in one of the right middle lobe pulmonary metastases are shown. Post-treatment the FDG avidity in the bony lesions is much reduced and the right middle lobe lesion had completely resolved

Sagittal MR images of thoracolumbar spine: a pre-treatment STIR demonstrates the lesion at T12 with extension through the anterior vertebral body bony margin; b pre-treatment T2 demonstrates tumour projecting into the T12 prevertebral soft tissue (arrowhead) and into the neural foramen at L1 (long arrow); and c post 3 cycles of pembrolizumab, there is no longer prevertebral extension of tumour at T12 (arrowhead) and only ill-defined soft tissue remains around the L1 root (long arrow); lesions in the body of L1, L4 and L5 are also smaller

The patient commenced treatment with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, MSD) at 2 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks. The first cycle was complicated by fever without an identified source but there were no other immune-related adverse events. Restaging after cycle 3 showed a very good response to therapy with complete resolution of all but 4 of the pulmonary metastases. The largest nodule in the left lower lobe had reduced in diameter from 28 to 14 mm and peak SUV was 1.2 compared to 4.3 prior to treatment (Figs. 2b and 3b, d). The soft tissue component of the lesion at T12 had decreased in size and had a reduction in SUV from 14 to 6.1 (Figs. 2b and 4c). In addition, there was resolution of the soft tissue component anteriorly at L1, reduction in size of the lesion at L2 and better definition of the lesions at L4 and L5 (Fig. 4c). Clinically, his back pain resolved. After a further 6 cycles of pembrolizumab, progress imaging confirmed ongoing response to therapy, with complete resolution of active pulmonary metastases, a reduction in SUV at T12 from 6.1 to 4 and stable appearance on MR imaging (not shown). Treatment was ceased after a total of 9 cycles and at the most recent review 6 months since the last dose the clinical and radiological response has been sustained.

Discussion

PD-L1 expression has been evaluated in a variety of sarcomas. The series reported by Raj et al. identified that 39 % of Ewing sarcomas expressed PD-L1 compared with 36 % of osteosarcomas and 97 % of leiomyosarcomas [14]. Kozak et al. retrospectively analysed 36 tumour samples of patients with synovial sarcoma and found PD-L1 expression in 83 %, with expression associated with poorer outcomes [15]. Kim et al. reported a similar association in a study of soft tissue sarcomas [16]. Of note, there is evidence across most, but not all, tumour types of a relationship between PD-L1 expression and response rates to immune checkpoint blockade, however a lack of PD-L1 expression does not preclude a response to PD-1 inhibition [7, 17–20]. Despite the known expression of PD-L1 in sarcoma, the only report of immune checkpoint blockade is a small pilot study by Maki et al. of the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab in advanced synovial sarcoma, in which no objective clinical responses were seen [21]. Another rationale for the possible utility of PD-1 blockade in EWS is the presence of genomic instability [12, 13]. Response to PD-1 blockade in colorectal cancer has been correlated with MMR deficiency; however, there are conflicting reports of MMR status and response in gastric cancer [8, 11, 22].

The explanation for the immune therapy response in our patient is unclear. Unfortunately, archival tissue was unavailable and hence we were unable to correlate response with PD-L1 expression (or lack of) in this case. His clinical course was relatively indolent for metastatic EWS and he had received extensive prior radiotherapy, which may have heightened the immune response. There is emerging evidence to suggest a role for radiotherapy in enhancing responses to immune therapy through a variety of mechanisms [23, 24].

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of response of EWS to immune checkpoint blockade with pembrolizumab. The patient’s recurrent metastatic EWS responded poorly to multiple conventional and experimental chemotherapeutic agents over the preceding 4 years, and his early relapse is a well-recognised poor prognostic marker in recurrent EWS [4–6, 25]. We suggest that further evaluation of PD-1-directed therapy in recurrent and metastatic EWS is warranted and await the results of the SARC028 phase II study investigating efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in advanced soft tissue and bone sarcomas [26]. In addition, evaluation of pre-treatment and on-treatment biomarkers in SARC028 and future studies will refine our ability to predict response to immune checkpoint blockade in individual patients and monitor treatment efficacy [20, 26].

Abbreviations

- EWS:

-

Ewing sarcoma

- MMR:

-

mis-match repair

- PD-1:

-

programmed cell death-1

- PD-L1/2:

-

programmed cell death ligand-1/2

- SUV:

-

standardised uptake value

References

de Alava ELS. Sorensen PH Chapter 19: Ewing sarcoma. In: Fletcher CDM BJ, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC; 2013.

Gurney GJ SA, Bulterys M. Malignant bone tumours. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program; 1999. NIH Pub No. 99-4649; 1999.

Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, et al. Ewing sarcoma: current management and future approaches through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3036–46.

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Billups CA, Kun LE, et al. Survival after recurrence of Ewing tumors: the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience, 1979–1999. Cancer. 2002;94:561–9.

Bacci G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, et al. Therapy and survival after recurrence of Ewing’s tumors: the Rizzoli experience in 195 patients treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy from 1979 to 1997. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1654–9.

Barker LM, Pendergrass TW, Sanders JE, Hawkins DS. Survival after recurrence of Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4354–62.

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54.

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–28.

Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30.

Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9.

Lin AY, Lin E. Programmed death 1 blockade, an Achilles heel for MMR-deficient tumors? J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:124.

Ohali A, Avigad S, Cohen IJ, et al. High frequency of genomic instability in Ewing family of tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;150:50–6.

Ferreira BI, Alonso J, Carrillo J, et al. Array CGH and gene-expression profiling reveals distinct genomic instability patterns associated with DNA repair and cell-cycle checkpoint pathways in Ewing’s sarcoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:2084–90.

Raj S, Bui M, Gonzales R, Letson D, Antonia SJ. Impact of PDL1 expression on clinical outcomes in subtypes of sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:iv494–510.

Kozak KS-CA, Rembiszewska A, Podgorska A, Kosela Patercyzyk HM, Przby J, Gos A, Switaj T, Prochorec-Sobieszek M, Rutkowski P. Programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression and prognostic value in synovial sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Supplement 4):494–510.

Kim JR, Moon YJ, Kwon KS, et al. Tumor infiltrating PD1-positive lymphocytes and the expression of PD-L1 predict poor prognosis of soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82870.

Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–7.

Grosso J HC, Inzunza D, Cardona DM, Simon JS, Gupta AK, Sankar V, Park J, Kollia G, Taube JM, Anders R, Jure-Kunkel M, Novotny J, Jr., Taylor CR, Zhang X, Phillips T, Pauline Simmons P and Cogswell J. Association of tumor PD-L1 expression and immune biomarkers with clinical activity in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors treated with nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538). J Clin Oncol 2013;31 (suppl; abstr 3016).

Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 Blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med 2016. [Epub ahead of print].

Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:275–87.

Maki RG, Jungbluth AA, Gnjatic S, et al. A pilot study of anti-CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab in patients with synovial sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2013;2013:168145.

Chen KH, Yuan CT, Tseng LH, Shun CT, Yeh KH. Case report: mismatch repair proficiency and microsatellite stability in gastric cancer may not predict programmed death-1 blockade resistance. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:29.

Formenti SC, Demaria S. Combining radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy: a paradigm shift. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:256–65.

Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:687–95.

Leavey PJ, Mascarenhas L, Marina N, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with Ewing sarcoma (EWS) at first recurrence following multi-modality therapy: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:334–8.

Burgess MA CJ, Reinke DK, Riedel RF, George S, Movva S, Van Tine BA, Davis LE, Schuetze S, Hu J, Attia S, Priebat DA, Reed DR, D’Angelo SP, Okuno SH, Maki RG, Patel S, Baker LH, Tawbi HA. SARC 028: A phase II study of the anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab (P) in patients (Pts) with advanced sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (suppl; abstr TPS10578).

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Funding

Nil.

Authors’ contributions

GM prepared the draft and VB, MJ, AM, JS, AH, PS and MT all reviewed and contributed to the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written consent to publish this report was obtained from the patient.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

McCaughan, G.J.B., Fulham, M.J., Mahar, A. et al. Programmed cell death-1 blockade in recurrent disseminated Ewing sarcoma. J Hematol Oncol 9, 48 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0278-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0278-x