Abstract

Background

Copy number variants (CNVs) associated with developmental delay and intellectual disability (DD/ID) continue to be identified in patients. This article reports identification of a chromosome 1q22 microdeletion as the genetic cause in a Chinese family affected by ID.

Case presentation

The proband was a 19-year-old pregnant woman referred for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis at 18 weeks of gestation. She had severe ID with basically normal stature (height 154 cm [0 SD], weight 61 kg [− 0.2 SD], and head circumference 54 cm [− 1.12 SD]). Her distinctive facial features included a prominent forehead; flat face; flat nasal bridge and a short upturned nose; thin lips; and small ears. The proband’s father was reported to have low intelligence, whereas her mother was of normal intelligence but with scoliosis. Chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) reveals that the proband, her father and the fetus all carry a 1q22 microdeletion of 936.3 Kb (arr[GRCh37] 1q22 (155016052_155952375)×1), which was not observed in her mother and paternal grandparents and uncles, suggesting a de novo mutation in the proband’s father. The microdeletion involves 24 OMIM genes including ASH1L (also known as KMT2H and encoding a histone lysine methyltransferase). Of note, haploinsufficiency of ASH1L has been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Based on the inheritance of the detected CNV in the pedigree and similar CNVs associated with ID in public databases (Decipher, DGV and ClinVar) and literature, the detected CNV is considered as pathogenic. The family chose to terminate the pregnancy.

Conclusions

The identified 1q22 microdeletion including ASH1L is pathogenic and associated with ID. This case broadens the spectrum of ID-related CNVs and may be useful as a reference for clinicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

DD/ID refers to a large group of developmental disorders characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviors [1]. The onset of DD/ID usually is observed before the age of 18 years. Patients at the age of 5 years or younger who present with reasoning and learning difficulties and motor developmental delay are diagnosed as DD, whereas those who become symptomatic at the age over 5 years are regarded as ID [2]. DD/ID, with an estimated incidence of 1–3%, can be highly heterogeneous in clinical phenotype and genetic etiology [2]. About 25–50% DD/ID is associated with genetic alteration, such as 21, 18, or 13 trisomy or submicroscopic deletion/duplication [3].

CMA is featured by whole genome coverage, high resolution and rapid detection [4]. It has been recommended as the first-line clinical diagnostic test for individuals with unexplained DD/ID, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) or multiple congenital anomalies (MCA) [5]. CMA can not only detect submicroscopic chromosomal imbalances, but also delineate the size and gene content of the detected segment. This is crucial for phenotype/genotype correlation and for identifying candidate genes involved in the development of certain anomalies [6].

The present case documented the clinical phenotype and genetic analysis of a Chinese family affected by ID using CMA.

Case presentation

The proband was a 19-year-old pregnant woman who was referred to the department of medical genetics at the hospital for prenatal diagnosis due to a family history of intellectual disability. She was delivered vaginally at full-term. During the neonatal period, she was hypotonic and very passive. Her growth milestones were recalled. She walked at 1 year and 8 months of age, and learned to say “mama” at 2 years. She talked at nearly 3 years and showed severe ID. She began the first period of menstrual at the age of 13 years, and got married at 18 years. She was in pregnancy at 18 weeks’ gestation when referred for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis. She had facial dysmorphism including a prominent forehead; flat face; flat nasal bridge and a short upturned nose; thin lips; and small ears (Fig. 1). Examinations in psychological clinic showed that her height was 154 cm [0 SD]; weight was 61 kg [− 0.2 SD]; and head circumference was 54 cm [− 1.12 SD] [7, 8]. Her IQ score was 32 as accessed by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised China (WAIS-RC). In terms of the scale, a score ≤ 75 is considered as low intelligence, and a score of 32 suggests severe ID. Reportedly, she was able to care for herself in daily life. Clinical observation showed that she was introverted; seldom talked; had dementia and social dysfunction without depression and anxiety. Both her electroencephalogram (EEG) and brain MRI result were normal. No history of heart diseases was noted. Her father was reported to have low intelligence, but an on-site examination for her father was not achieved. Her mother was of normal intelligence but had scoliosis. Her paternal grandparents and uncles and the fetus’ father had no noticeable congenital anomalies.

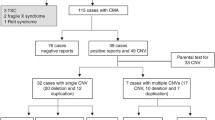

Written informed consent was obtained from the family (The proband was under the guardianship of her mother). Peripheral blood for each participant and the amniotic fluid of the proband were drawn for genetic testing. Heart rate, blood pressure and electrocardiogram of the proband were monitored before amniocentesis. Conventional G-banded karyotype analysis showed a normal female karyotype (46,XX) in the proband. However, CMA using the CytoScan 750 K Array from Affymetrix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) revealed a 936.3 kb heterozygous deletion of chromosome 1q22 (arr[GRCh37] 1q22 (155016052_155952375)×1) in the proband (Fig. 2). The microdeletion was also detected in the proband’s father (II-2) and the fetus (IV-1), but absent in her mother (II-1), grandparents (I-1, I-2) and paternal uncles (II-3, II-4). Other members within the pedigree were not tested. For all tested individuals, no other CNVs were detected except known polymorphisms (frequency > 1%).

The SNP-array results of tested members from the Chinese family affected by intellectual disability. The proband (III-1), her father (II-2) and the fetus (IV-1) all contain a 936.3 kb heterozygous deletion of chromosome 1q22 (arr[GRCh37] 1q22 (155016052_155952375)×1). No significant CNVs were identified in the proband’s mother (II-1), grandparents (I-1 and -2) and paternal uncle II-3

In search of public databases (Decipher, DGV and ClinVar) and literature, a few cases reported copy number losses of the 1q22 region including ASH1L and the associated phenotypes including ID with MCA (Table 1). Furthermore, haploinsufficiency of ASH1L is strongly associated with DD/ID and MCA in multiple individual cases [9, 10]. On the basis of these observations, plus the co-segregation of genotype and phenotype in the current case, the detected CNV is considered to be pathogenic, being in line with the guidelines from the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) [11]. After full consideration, the family chose to terminate the pregnancy.

Discussion

The identified microdeletion in the proband involves 43 known genes, of which 24 were OMIM genes, including ADAM15 (OMIM: 605548), EFNA4 (OMIM: 601380), EFNA3 (OMIM: 601381), EFNA1 (OMIM: 191164), SLC50A1 (OMIM: 613683), DPM3 (OMIM: 605951), TRIM46 (OMIM: 600986), MUC1 (OMIM: 158340), THBS3 (OMIM: 188062), MTX1 (OMIM: 600605), GBA (OMIM: 606463), SCAMP3(OMIM: 606913), CLK2 (OMIM: 602989), HCN3(OMIM: 609973), PKLR (OMIM: 609712), FDPS (OMIM: 134629), ASH1L (OMIM: 607999), YY1AP1 (OMIM: 607860), DAP3 (OMIM: 602074), GON4L (OMIM: 610393), SYT11 (OMIM: 608741), RIT1 (OMIM: 609591), RXFP4 (OMIM: 609043), and ARHGEF2 (OMIM: 607560). Among these OMIM genes, TRIM46, CLK2, ASH1L, GON4L and ARHGEF2 are marked by a high probability of being loss of function intolerant (pLI ≥ 0.9), in contrast to other genes with a moderate (RIT1 pLI: 0.67) or low probability. Therefore, haploinsufficiency of the genes with high pLI is particularly concerned. In OMIM database, the phenotypes of heterozygous loss of TRIM46, CLK2, GON4L and ARHGEF2 in humans have not been fully documented, whereas a handful of individual patients featured by intellectual disability are reported to carry a heterozygous nonsense or frame-shift mutation of ASH1L, which results in truncated and nonfunctional protein [12,13,14]. The documented cases highly support that alteration in gene dosage of ASH1L is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. In more recent studies, additional de novo loss of function variants of ASH1L have been identified, and all patients presented with mild to severe DD/ID [10]. Interestingly, a 532.9 kb heterozygous deletion (arr[GRCh37] 1q22 (155271366_155804269)×1) was found in a 7-year-old boy who had microcephaly and severe ID with MCA [9, 10]. Notably, the microdeletion identified in the present case fully encompasses the 532.9 kb segment and involves more OMIM genes. Based on these observations, the 1q22 microdeletion of 936.3 Kb including ASH1L is regarded as pathogenic and associated with ID. Importantly, not only micro-deletions, but also duplications within 1q22 may cause neurodevelopmental abnormalities (Table 1).

Though the pathogenicity of ASH1L haploinsufficiency is evident, contribution of other OMIM genes (e.g. CLK2, ARHGEF2 and RIT1) to the phenotypes in this case cannot be fully excluded [15,16,17]. It is noteworthy that some clinical features of the proband resemble certain phenotypes such as broad forehead, broad nasal bridge, and learning/intellectual disabilities described in Noonan syndrome (NS), an autosomal-dominant disorder [15]. In a more recent report on the molecular and phenotypic spectrum of a Chinese NS cohort (n = 103), 6 out of 7 patients with RIT1 mutation presented with various congenital heart defects, and a high rate (4 out of 7) of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was observed in RIT1 mutation-positive patients [18]. With regard to the proband in this report, although cardiac imaging examination was not performed, heart rate, blood pressure and electrocardiogram were recorded prior to ultrasound-guided amniocentesis. The normal readouts plus no previous history of heart disease suggested that it was unlikely that the patient had cardiomyopathy. Taking the potential involvement of multiple functional genes into account, it remains to be further elucidated whether this 1q22 microdeletion causes contiguous gene syndrome.

ASH1L encodes a histone lysine methyltransferase that catalyzes mono- and di-methylation of histone 3 lysine 36 (H3K36). This gene is highly expressed in both embryonic and adult human brains [19]. An inadequate amount of ASH1L protein due to copy number loss of the gene may affect epigenetic regulation of the expression program involved in embryo and brain development. Animal model studies show that mice in homozygosity of a hypomorphic ASH1L allele exhibited growth insufficiency, skeletal transformations and impaired fertility associated with developmental defects of reproductive organs [20]. In this case, the 1q22 microdeletion including ASH1L resulted from a de novo mutation in the proband‘s father. Phenotipically, both the proband and her father were fertile, suggesting that haploinsufficiency of ASH1L may not cause infertility in humans.

In summary, the present case shows the clinical phenotype of the proband in a Chinese family affected by ID and identification of a 1q22 microdeletion including ASH1L as the genetic cause in the pedigree. This case broadens the spectrum of ID-related CNVs and may be useful as a reference for clinicians. Apart from clinical findings, certain social and ethic issues also are brought into our sight by the case. For instance, was the pregnancy of the proband’s own free will? How should the fate of the fetus be decided? Though it may take time to find out the best solutions for the scenario resembling the case, there is no doubt that more social care is demanded with regard to women patients with intellectual disability.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cappuccio G, Vitiello F, Casertano A, et al. New insights in the interpretation of array-CGH: autism spectrum disorder and positive family history for intellectual disability predict the detection of pathogenic variants. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;42:39.

Vasudevan P, Suri M. A clinical approach to developmental delay and intellectual disability. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(6):558–61.

Srour M, Shevell M. Genetics and the investigation of developmental delay/intellectual disability. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(4):386–9.

Levy B, Wapner R. Prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(2):201–12.

Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(5):749–64.

Kaminsky EB, Kaul V, Paschall J, et al. An evidence-based approach to establish the functional and clinical significance of copy number variants in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Genet Med. 2011;13(9):777–84.

Li Y, Zheng L, Xi H, et al. Stature of Han Chinese dialect groups: a most recent survey. Sci Bull. 2015;60(5):565–9.

Li Y, Zheng L, Yu K, et al. Variation of head and facial morphological characteristics with increased age of Han in southern China. Chin Sci Bull. 2013;58(4):517–24.

Faundes V, Newman WG, Bernardini L, et al. Histone lysine Methylases and Demethylases in the landscape of human developmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(1):175–87.

Shen W, Krautscheid P, Rutz AM, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Dugan SL. De novo loss-of-function variants of ASH1L are associated with an emergent neurodevelopmental disorder. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62(1):55–60.

Kearney HM, Thorland EC, Brown KK, Quintero-Rivera F, South ST. American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet Med. 2011;13(7):680–5.

de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BW, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1921–9.

Okamoto N, Miya F, Tsunoda T, et al. Novel MCA/ID syndrome with ASH1L mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(6):1644–8.

Stessman HA, Xiong B, Coe BP, et al. Targeted sequencing identifies 91 neurodevelopmental-disorder risk genes with autism and developmental-disability biases. Nat Genet. 2017;49(4):515–26.

Kouz K, Lissewski C. Genotype and phenotype in patients with Noonan syndrome and a RIT1 mutation. Genet Med. 2016;18(12):1226–34.

Nothwang HG, Kim HG, Aoki J, et al. Functional hemizygosity of PAFAH1B3 due to a PAFAH1B3-CLK2 fusion gene in a female with mental retardation, ataxia and atrophy of the brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(8):797–806.

Ravindran E, Hu H, Yuzwa SA, Hernandez-Miranda LR, Kraemer N. Homozygous ARHGEF2 mutation causes intellectual disability and midbrain-hindbrain malformation. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(4):e1006746.

Li X, Yao R, Tan X, et al. Molecular and phenotypic spectrum of Noonan syndrome in Chinese patients. Clin Genet. 2019;96(4):290–9.

Miller JA, Ding SL, Sunkin SM, et al. Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature. 2014;508(7495):199–206.

Brinkmeier ML, Geister KA, Jones M, Waqas M, Maillard I, Camper SA. The histone methyltransferase gene absent, small, or homeotic Discs-1 like is required for Normal Hox gene expression and fertility in mice. Biol Reprod. 2015;93(5):121.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the family for participation in the present study.

Funding

This study was supported by grants (2015TP2029, 2017SK1030, 2019SK1010 and 2019SK1013) from Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. Xi and J. Peng recruited the patients. H. Xi and W. Xie wrote the manuscript. Y. Peng, S. Yang and J. Pang performed clinical analysis. J. Pang and N. Ma performed genetic tests. Hua Wang designed the study and analyzed the data. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for genetic tests. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xi, H., Peng, Y., Xie, W. et al. A chromosome 1q22 microdeletion including ASH1L is associated with intellectual disability in a Chinese family. Mol Cytogenet 13, 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-020-00483-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-020-00483-5