Abstract

Background

Pure interstitial duplications of chromosome band 4p16.3 represent an infrequent chromosomal finding with, to the best of our knowledge, only two patients to date reported.

Case presentation

We report on a 13-year-old boy showing a set of dysmorphic facial features, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, learning difficulties, speech and cognitive delays, overgrowth and musculoskeletal anomalies in whom an interstitial duplication of about 400 kb in 4p16.3 was detected by SNP-array analysis. The duplication includes the complete coding sequence of FAM53A, SLBP, TMEM129 and TACC3 genes and the first exon of the FGFR3 gene. Phenotypic comparison with previously described patients harboring a microduplication of similar size and position contributes to better define the clinical correlation of 4p16.3 microduplications, suggesting the existence of a novel distinct and phenotypically recognizable syndrome. In addition, being the duplication identified in our case the smallest so far reported, it allowed us to refine the smallest region of overlap among patients to 222 kb, enabling a more accurate genotype-phenotype correlation for 4p16.3 microduplications.

Conclusions

Our case report provide clinical and molecular evidences supporting the existence of a novel 4p16.3 microduplication syndrome. The genes FAM53A, TACC3 and FGFR3 seems to play a key role in the etiology of the clinical phenotype. Interestingly, our patient is the oldest described so far and for this reason useful to delineate the long-term prognosis of these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Small (<1 Mb in size) and pure interstitial microduplications of the distal short arm of chromosome 4 are rare; to the best of our knowledge, only two patients have been to date reported. Some years ago, Hannes et al. [1] described a 23-month-old boy whit neurodevelopmental delay, seizures, glaucoma of the left eye and dysmorphic features in whom a de novo submicroscopic (560 kb) duplication of 4p involving the Wolf-Hirschhorn critical region (WHSCR) has been identified. Later, Cyr at al. [2] using a high-density oligonucleotide microarray described the first patient carriers of a de novo 506 kb microduplication in 4p16.3, distal to WHSCR, showing developmental delay, seizures, macrocephaly, unilateral glaucoma, abnormal hands and dysmorphic features.

In this study, we report an additional patient with the smallest overlapping duplication in 4p16.3, detected by SNP-array analysis, not including the WHSCR delineating the duplications’ phenotype. In addition, refinement of the smallest region of overlap (SRO) to 222 kb highlights interesting genes as candidates for the common observed clinical features, suggesting that the duplication in 4p16.3, distal to WHSCR, may represent a novel clinically recognizable condition.

Case presentation

Case report

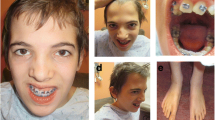

The male patient was referred for the first time at the age of 10 years for evaluation of autistic features, learning difficulties, speech and cognitive delays. No information are available on family history since he was adopted. Physical examination at 13 years of age revealed auxological parameters above the average (weight >97th centile; height between the 90th and 97th centile) and dysmorphic features including high forehead with frontal bossing, small palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, hypertelorism (>2 SD), dental abnormalities, high arched palate, micrognathia, short neck (Figure 1). In addition, hyperopia and skeletal anomalies (scoliosis), gynecomastia and bilateral pes planus were reported.

Neuropsychiatric evaluation showed speech delay, mild cognitive impairment (QI 68), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Also, the patient showed walking abnormalities (uncertain gait), clumsiness.

Abdominal ultrasound examination and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal. Genetic evaluation revealed a normal 46,XY karyotype while DNA analysis for FMR-1 gene excluded the diagnosis of fragile X (FRAXA) syndrome.

Results

SNP array analysis showed a 4p16.3 duplication of a minimum size of 393 kb, from nucleotide nt 1,405,662 (first duplicated probe: CN_1080836) to nucleotide nt 1,798,461 (last duplicated probe: CN_1081687), and a maximum size of 413 kb, from nucleotide nt 1,390,388 (last present probe before the duplication: CN_1069802) to nucleotide 1,804,276 (first present probe after the duplication: SNP_A-2213611).

The duplicated region encompass the entire coding sequences of FAM53A, SLBP, TMEM129, TACC3 genes and the 5′ end of the FGFR3 gene (data not shown). According to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) 2013, molecular karyotype of the patient was arr[hg19]4p16.3(1,405,662-1,798,461)×3. There were no other clinically significant genomic alterations identified.

Discussion

We report on a 13-year-old boy with an interstitial 393 kb duplication on the short arm of chromosome 4 (4p16.3). To our knowledge, there are only two patients reported in the literature carriers of a duplications similar in size and position to the one identified in our patients [1,2]. The clinical phenotype of our patient, similarities and differences with previously reported cases are discussed in detail and summarized in Table 1 while the location of the duplications is shown in Figure 2. The clinical features shared by all three individuals include psychomotor and language delay, musculoskeletal anomalies, eyes alterations as well as craniofacial anomalies (high forehead, frontal bossing, epicanthal folds, hypertelorism/abnormal palpebral fissures, short neck) suggesting that the cryptic 4p16.3 duplications results in a novel recognizable microduplication syndrome. Seizure, MRI anomalies, abnormal ears, high arched palate and growth alterations (macrocephaly in the patient reported by Cyr et al., overgrowth in our) are also significant issues in these patients (2/3). Others phenotypes observed are hypotonia in the patient reported by Hannes et al. [1], mild intellectual disability and micrognathia in our case. Some differences in clinical presentations among the 4p16.3 microduplicated patients could be explained by the influence of the genetic background of the rest of the genome and/or the variable size and gene content of the rearrangements. These factors could have additional or modifying influences on the clinical features.

Schematic representation of the 4p16.3 duplications in the present and previously reported patients based on the UCSC genome browser 2009 assembly (GRCh37/hg19) [ http://genome.ucsc.edu/ ].

At a molecular level the small size (393 kb) of the duplication we present here allowed us to identify the SRO among the patients and focus our attention on interesting candidate genes that could be associated to the common traits reported.

The minimal duplicated region shared by all three patients is about 222 kb (1,575,789-1,798,461 bp), has never been reported as copy number polymorphism (CNP) in the Database of Genomic Variant and encompass the entire sequence of the genes FAM53A, SLBP, TMEM129, TACC3 and the 5′ end of the FGFR3 gene. Of these genes, FAM53A and TACC3 are the best candidate for the neurodevelopmental features because highly expressed in the early embryonic central nervous system (FAM53A) suggesting critical roles in the neuronal development [3] or encoding a protein (TACC3) that controls the genesis of neurons from radial glial progenitor cells (RGCs) during cortical development [4]. In addition, mutations of the murine Tacc3 leads to retarded growth, apoptosis of hematopoietic stem cells and facial clefting [5]. The apparent role in facial development makes this gene of interest also for the craniofacial traits of the 4p16.3 microduplicated patients discussed: some of the affected tissues are equivalent to those that are dysgenic in the patients (i.e. the tissues derived from the fronto-nasal mass). Although these evidences suggest that TACC3 could be responsible for the dysmorphic facial features reported, functional studies, additional experimental and clinical data are needed to corroborate our hypothesis.

Regarding the growth alterations and the musculoskeletal malformations the best candidate is the gene FGFR3 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3) that is a regulator of bone growth. Mutations in this gene has been associated with at least ten human disorders where skeletal alterations represent the principal clinical presentations. It is interesting to highlight the fact that the features concerning the growth (overgrowth in our patient), or at least some of its parameters (macrocephaly in the patient described by Cyr et al.), of patients with duplication of FGFR3 are opposed to that of Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome (WHS; del4p16.3) patients (microcephaly, growth retardation). This phenomenon supports the hypothesis of mirror phenotypes resulting from reciprocal deletion/duplication in chromosomal regions containing dosage sensitive genes as described for other copy number variants (16q11.2, 7q11.23, 5q35) [6,7].

In all patients to date reported, eyes anomalies have been documented such as glaucoma in the patient described in the Hannes’ paper, the iris pigmentation- heterochromia reported by Cyr et al. and the hyperopia of our patient. Since this clinical evidence, in agreement with Cyr et al., we consider the 4p16.3 locus very important in ocular development although, at this time, we cannot be able to explain the biological mechanism related to 4p16.3 trisomy underlying these alterations. Evaluation of more patients is needed to clarify this point.

Our patient does not share the seizures that are present in the other two individuals. In contrast to the 4p16.3 duplications described by Hannes et al. [1] and Cyr et al. [2] the duplication identified in the present patient do not encompass the LETM1 gene supporting the hypothesis that overexpression of this gene may results in seizure [2].

Needs to be elucidated the involvement of the SLBP and TMEM129 genes in the etiology of the phenotype in patients with dup4p16.3. The first encodes an RNA-binding protein that recognize a stem-loop structure in 3′ non-coding sequence of histone mRNAs essential for maturational cleavage and efficient translation of the encode histone [8] while the function of the latter remains to be explored. Their contribution to the phenotype, if any, is unknown. Evaluation of additional patients with well-characterized 4p16.3 duplication and/or point mutations in this region will be useful to elucidate the role of individual genes for the clinical presentations.

Of note, our patients is the only one in which a consistent pattern of neurobehavioral features including ADHD, has been documented. Since the other two patients are too young, we cannot exclude that they will show behavioral alterations in the feature thus we suggest a periodic neurobehavioral clinical evaluation in 4p16.3 microduplication carriers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this report we provide clinical and molecular evidences supporting the existence of a novel 4p16.3 microduplication syndrome. The shared clinical features between our patient and those in previous reports include psychomotor and language delay, skeletal anomalies and a particular pattern of facial dysmorphisms. Narrowing the SRO to include only five genes we performed a more detailed genotype-phenotype correlation suggesting the FAM53A, TACC3 and FGFR3 genes as candidates for the clinical manifestation of this syndrome. Finally, being our patients the oldest reported so far he provides detailed clinical and phenotype informations across the lifespan facilitating a more accurate genetic counselling and anticipatory care.

Methods

SNP array analysis

Total DNA was obtained from peripheral blood using automated BioRobot EZ1 (Qiagen, Solna, Sweden). We checked it for quantity and purity using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Molecular karyotyping was performed using the high-resolution Genome Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) providing whole genome coverage with a density of 1.8 million markers, including 906,600 SNPs and 946,000 copy number markers. Labeling, hybridization, washing, scanning and image extraction were performed as previously described [9]. Copy number variations (CNVs) identified in this study and overlapping with annotated CNVs in Database of Genomic Variants (DGV; http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home), were not considered. Furthermore, we filtered all CNVs that had ≤50 contributing markers.

Consent

We obtained written informed consent from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Abbreviations

- WHSCR:

-

Wolf-Hirschhorn critical region

- SRO:

-

Smallest region of overlap

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CNVs:

-

Copy number variations

- DGV:

-

Database of Genomic Variants

- ISCN:

-

International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature

- CNP:

-

Copy number polymorphism

- RGCs:

-

Radial glial progenitor cells

- FGFR3 :

-

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3

References

Hannes F, Drozniewska M, Vermeesch JR, Haus O. Duplication of the Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome critical region causes neurodevelopmental delay. Eur J Med Genet. 2010;53(3):136–40.

Cyr AB, Nimmakayalu M, Longmuir SQ, Patil SR, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Shchelochkov OA. A novel 4p16.3 microduplication distal to WHSC1 and WHSC2 characterized by oligonucleotide array with new phenotypic features. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(9):2224–8.

Jun L, Balboni AL, Laitman JT, Bergemann AD. Isolation of DNTNP, which encodes a potential nuclear protein that is expressed in the developing, dorsal neural tube. Dev Dyn. 2002;224(1):116–23.

Yang YT, Wang CL, Van Aelst L. DOCK7 interacts with TACC3 to regulate interkinetic nuclear migration and cortical neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(9):1201–10.

Piekorz RP, Hoffmeyer A, Duntsch CD, McKay C, Nakajima H, Sexl V, et al. The centrosomal protein TACC3 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell function and genetically interfaces with p53-regulated apoptosis. EMBO J. 2002;21(4):653–64.

Somerville MJ, Mervis CB, Young EJ, Seo EJ, del Campo M, Bamforth S, et al. Severe expressive-language delay related to duplication of the Williams-Beuren locus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1694–701.

Rosenfeld JA, Kim KH, Angle B, Troxell R, Gorski JL, Westemeyer M, et al. Further Evidence of Contrasting Phenotypes Caused by Reciprocal Deletions and Duplications: Duplication of NSD1 Causes Growth Retardation and Microcephaly. Mol Syndromol. 2013;3(6):247–55.

Ling J, Morley SJ, Pain VM, Marzluff WF, Gallie DR. The histone 3′-terminal stem-loop-binding protein enhances translation through a functional and physical interaction with eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) and eIF3. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(22):7853–67.

Palumbo O, Mattina T, Palumbo P, Carella M, Perrotta CS. A de novo 11p13 Microduplication in a Patient with Some Features Invoking Silver-Russell Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2014;5(1):11–8.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant of the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2014) to MC, by the “5×1000” voluntary contributions and partially funded by the “Progetto Operativo Nazionale”, PON 2007–2013 LAB GTP (PON02_00619). We are grateful to the patient and his family for agreeing to take part in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MCDG carried out the clinical genetic diagnosis while EF, FNR and LC provided technical support for the molecular tests. OP and PP provided the SNP array analysis and the interpretation of results while MC supervised the study and reviewed the paper. OP wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Palumbo, O., Palumbo, P., Ferri, E. et al. Report of a patient and further clinical and molecular characterization of interstitial 4p16.3 microduplication. Mol Cytogenet 8, 15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-015-0119-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-015-0119-6