Abstract

Background

The Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) is a tool developed by the World Health Alliance for Patient Safety, to assist health professionals in improving patient safety during surgery. Numerous specialties have incorporated this into their clinical practice. The purpose of this study is to adapt and implement this tool within the field of podiatric surgery and to evaluate its impact upon safety standards and post-surgical complications.

Methods

An analytical, observational, longitudinal study has been performed retrospectively. The implementation of the Surgical Safety Checklist in podiatric surgery took place over a 10-month period. The sample is made up from the medical histories of patients who were operated on (n = 134) in the University of Seville’s podiatric clinic. The sample was divided into three groups: those prior to the implementation process (65 subjects), those after the implementation process: without the SSC (35 subjects) and those with the SSC (34 subjects). The safety standards included in the tool were analysed in conjunction with the results and post-operative complications.

Results

An improvement was seen in compliance with the Prophylaxis Protocol and the correct completion of the Informed Consent (p = 0.00), as well as a statistically significant relationship between the correct use of antibiotic prophylaxis and the use of the Surgical Safety Checklist (p = 0.049). The results demonstrate a reduction in the number of post-operative days (p = 0.012). No cases of surgery being performed in the wrong place were found in this study.

Conclusions

The Surgical Safety Checklist allows us to improve compliance with the safety protocols recommended by the scientific community, and consequently to reduce the incidence of complications related to surgery and to improve patient safety during elective podiatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Patient Safety has been discussed since the Aristotelian principle “primum non nocere” but it is still highly relevant today and has gained strength since the creation of the World Alliance for Patient Safety [1].

Finding the cause of adverse events in healthcare and a means of reducing their occurrence is a cause for concern for healthcare professionals and managers. The first publication that highlighted healthcare-related adverse events, and as such, sparked interest in offering safer healthcare and correctly identifying any adverse events in the sector was the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 1999 publication ‘To err is human: building a safer health system’ [2]. This estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die every year as a result of medical errors in the United States.

Other studies suggest that the incidence rate is between 2.9 and 16.6 [3–6]. The highest incidence of adverse events is registered in surgical specialities [7].

Given these figures, the World Alliance for Patient Safety outlines specific bi-annual goals. The Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) has been developed from two projects which they have carried out: “Clean Care is Safer Care” [8] and “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” [1]. It is an easy-to-use, measurable set of safety checks, adaptable to different healthcare settings.

It is well-known that fatigue, stress and the development of complex procedures reduces the precision and speed of the human memory [9, 10]. These studies demonstrate the utility of checklists as a safe and useful tool to help minimise human error.

De Vries [11] introduced a checklist encompassing a patient’s complete medical history. This was later adapted by other authors, including Boscá et al. [12] for use in interventional radiology, and Perea et al. [13] to dental surgery.

There are few studies related to patient safety in the field of podiatry. Jones y Levy (2012) [14] refer to the need to improve the educational model for podiatrists in terms of patient safety and in regards to error disclosure to improve professional development. Other publications in the field of podiatry address some patient safety standards, such as those related to antibiotic prophylaxis [15, 16], the incidence of thrombosis-embolism [17, 18], the surgical preparation of the skin [19–21] and the prevention of surgery in the wrong site [22, 23]. To date, the majority of the bibliography refers to isolated cases or short series on which empirical evaluations have been performed. Coheña et al. [24] are pioneers in this issue in podiatry, having proposed an adapted version of the SSC for podiatric surgery, without results.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of the SSC proposed by Coheña et al. in regards to safety standard compliance and the reduction of surgical complications in podiatric surgery.

Methods

Setting

Based on the SSC implementation guide in the Safe Surgery Saves Lives [1] programme, in order to implement the SSC in podiatric surgery there are 10 phases, these are identified in the Gantt chart, where each activity is recorded together with the time required for their implementation, (Table 1 Implementation phases). This process took ten months and took place in the Podiatric Clinic at the University of Seville (ACP).

Around 150 surgical podiatric procedures are carried out at this centre on an out-patient basis, from nail surgery to osteoarticular surgery with orthopaedic fixation devices under local anaesthetic. As a new tool in the field of podiatry and as recommended by other authors [25–27], an intensive training programme was undertaken during the implementation process before any data was collected. This programme included the development of a handbook, briefings and practical workshops.

Evaluation focused on identifying changes that occurred in patients as a result of using the SSC, comparing the three groups which the sample had been divided into: the pre-implementation group/the group without the SSC and the group with the SSC.

A retrospective quantitative review was made from certain documents from the medical histories as an indicator of the level of compliance to the safety standards established by the WHO. Following the same protocol as this study, the researchers are Doctors in Podiatry and experts in management and quality of care.

Study design

This analytical, observational and longitudinal study was retrospectively evaluated.

Simple random sampling was used and the sample size calculated using a formula where n is the sample size, N is the population size, Z is 0.05 y p is the reference variable.

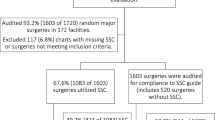

The sample consisted of 134 patients, divided into the previously described groups. (Fig. 1 Distribution of study groups)

.

The main variable is the degree of patient safety during surgery, in relation to compliance with the SSC-defined safety standards. Independent variables are shown in Table 2. (Table 2 Definition of the independent variables).

Results

The average age of the sample group was 47.49 years old, with a standard deviation of 22.124. In terms of gender, 73.9 % were female and 26.1 % male. In regards to the Surgical Risk Calculation, 51.5 % of patients were classed as ASA I, 47 % were classed as ASA 2 and only 1.5 % as ASA 3.

In terms of the type of surgery carried out, the highest percentage involved nail/skin surgery (66.4 %), followed by osteoarticular surgeries with implants (23.1 %) and osteoarticular surgeries without implants (10.4 %).

Correct compliance with the deep venous thromboembolic prophylaxis protocol (DVTPP)

Through the use of Pearson’s Chi-square Test, p = 0 (>0.05) a significant relationship is observed between the “WITH checklist group” and the correct practice of DVTPP. (Table 3A-B Comparison chart: Correct compliance with the DVTPP risk assessment and Chi-square test). The protocol was proposed by Autar R. [28] and was incorporated into podiatric surgical care at the ACP. The results of this study demonstrate that the SSC helps to improve compliance with the DVTPP. Truran [29], in his pre-post SSC implementation study, compares the compliance rates with the DVTPP, noting that non-compliance fell from 6.9 % to 2.1 %. This study found that the non-compliance rate was 68 % in the period prior to the implementation of the SSC, a figure that decreased to 24 % in the without SSC group and to 8 % in the with SSC group. It could be argued that this difference is due to the increased awareness of patient safety after the implementation period. The high levels of non-compliance found during this study in comparison to that of other studies could be explained by a failure to adhere to the protocol. This is likely because cases of thromboembolic complications in podiatric surgery are much fewer than in general surgery where these types of complications are common and stricter protocols exist.

Correct antibiotic prophylaxis pratice

Antibiotic prophylaxis is a controversial issue among health professionals, including podiatrists; nonetheless, the correct use of antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of post-surgical complications, offering patients health benefits and an increased quality of care, as well as having financial repercussions [30].

This study makes use of the recommendations made by Córdoba et al. [15] and Mosquera et al. [16] in their reviews as a means of assessing the usefulness of antibiotic prophylaxis. The results of this study demonstrate a significant relationship between the use of the SSC and the correct usage of antibiotic prophylaxis (p = 0.049). (Table 4 Correlation between the use of the SSC and correct use of antibiotic prophylaxis). Similarly, other authors [31] also note a significant improvement in the correct usage of antibiotic prophylaxis (57 % in the period prior to the SSC and 77 % in the period post). Rydenfält [32] observed that the standard associated with antibiotic prophylaxis in the SSC was one of the easiest to comply with.

Surgical site infection rate

De Vries [33] and Tillman [34] indicate that surgical site infection is the most frequent postsurgical complication and one with the highest impact upon the health/illness process of the patient, satisfaction levels and healthcare spending. According to Butterworth [35] and Zgonis [36] an infection rate of between 0.5 and 6.5 % is accepted as normal in elective foot-ankle surgery amongst podiatric surgeons. This study found a much higher total surgical site infection rate (15.3 %) than that accepted as normal by these authors. This can be explained by the teaching nature of the centre where this study was undertaken and the inherent bias of the medical histories involved. In the Table 5 (Table 5 Comparative analyses of data on surgical site infection) shows the comparative figures between this study and the research of Bliss [37], Tillman [34] and Haynes [38]. A reduction in the surgical site infection rates between the different groups are observed, reflecting lower infection rates in the groups where the SSC was used.

Furthermore, a significant relationship is observed between the reduction in surgical site infection rate and antibiotic prophylaxis (p = 0.019) (Table 6 A-B Relationship between surgical site infection and the correct usage of antibiotic prophylaxis). This is something which leads us to believe that an indirect correlation exists between the use of the SSC and the reduction in the surgical site infection rate.

Correct completion of informed consent

Numerous authors [39, 40] highlight the importance of patient-surgeon communication and consider the inclusion of the patient in their treatment the fundamental premise of healthcare. The informed consent form is a scientifically endorsed tool available to evaluate this relationship. Yet, in clinical practice is not always employed correctly, impacting upon communication, safety and affording the patient a grounds for claim [41].

The results of this study demonstrate a connection between the use of the SSC and higher levels of compliance and completion of the informed consent in the surgical process. De Vries [42] analysed 294 complaints made to Dutch health professionals, he indicated that 100 % of the 23 complaints registered in relation to the informed consent could have been avoided through the use of the SSC. Indeed, Cavallini [43], through incorporating the SSC into the quality programme at the centre where his study was undertaken, increase the informed consent completion rate to 99.76 %.

Number of post-operative days

The Kruskal-Wallis test for independent samples was used to associate the “post-operative days” independent variable to the study’s different groups, establishing a significance level of 0.05. This study found a significant relationship between the use of the SSC and the reduction of post-operative days, as is shown in Fig. 2 (Fig. 2 Comparative graphic on the number of postsurgical days) and Table 7 (Table 7 Statistical data on number of postoperative days).

This result confirms that the SSC affords the surgical team a visual and verbal reminder of the recommended safety measures, thereby reducing reliance on memory and improving compliance with basic safety standards [32, 39–43], consequently reducing the post-surgical period.

A retrospective analysis of medical histories was used in this study. The quality of the data collected was dependent upon the quality of the documentation in the medical and legal records. Given that compiled data may not directly reflect clinical practice, and therefore, as Panesar et al. [44] suggests, an infra-supra register might exist, Soria-Aledo [45] acknowledged this as a limitation in their studies. This study was able to minimise the Hawthorne effect by dividing the sample into three groups, as has been described by various authors [29, 46].

Conclusions

Just as the attitude and motivation of professionals can change, so can clinical practice. It is therefore necessary to establish a monitoring process for the SSC, performing audits and re-editing where necessary in order to make it more efficient and effective for professionals. Significant improvements have been seen in the utilization of patient safety protocols such as the DVTPP and antibiotic prophylaxis, as well as a reduction in post-operative days. These changes improve, both directly and indirectly overall patient safety, reducing surgical complications such as surgical site infections. After analysing all of the tests used to evaluate the SSC implementation process in podiatric surgery, we believe the study’s objectives have been fulfilled and confirm that the SSC is a useful and effective tool in the improvement of patient safety. We believe that further studies, over longer timeframes and in other podiatric surgical centres are necessary in order to gather further scientific evidence.

Ethical considerations

This investigation project meets with the approval and acceptance of the Ethical Committee of Experimenting of the University of Seville to investigate with human subjects and it adjusts to the current regulations in Spain and the European Union. To finish, informed consent was obtained of each participant after being completely informed before their participation in this study.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SSC:

-

Surgical Safety Checklist

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- IC:

-

Informed Consent

- DVTPP:

-

Deep Venus Tromboembolic Prophylaxis Protocol

References

Guidelines for Safe Surgery. World Health Organization. 1st ed. 2008.

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

Aranaz J, Aibar C, Vitaller J, Mira J, Orozco D. Estudio APEAS: estudio sobre la seguridad de los pacientes en Atención Primaria de Salud. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo 2008; 2011.

Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. Br Med J. 2001;322:517–9.

Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, Orav EJ, Zeena T, Williams EJ, et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38:261–71.

Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamilton JD. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1995;163:458–71.

Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Estudio nacional sobre los efectos adversos ligados a la hospitalización. 2005.

Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Boyce J. The World Health Organization guidelines on hand hygiene in healthcare and their consensus recommendations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:611–22.

Lorist MM, Boksem MA, Ridderinkhof KR. Impaired cognitive control and reduced cingulate activity during mental fatigue. Cogn Brain Res. 2005;24:199–205.

Miller G. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev. 1956;63:81–97.

De Vries E, Dijkstra L, Smorenburg SM, Meijer RP, Boermeester MA. The Surgical patient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist optimizes timing of antibiotic prophylaxis. Patient Saf Surg. 2010;4.

Boscá-Mayans MR, Arana E, Sánchez-Aparisi E. Diseño de una lista de verificación para radiología intervencionista. Enferm Clin. 2012;22:299–303.

Perea B, Santiago A, García F, Labajo E. Proposal for a surgical checklist for ambulatory oral surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:949–54.

Jones LJ, Levy LA. An Educational Model for Patient Safety and Disclosure of Medical Error in Podiatric Medicine. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2012;102:505–11.

Córdoba A, Ruiz G, Canca A. Algorithm for the management of antibiotic prophylaxis in onychocryptosis surgery. Foot. 2010;20:140–5.

Fernández AM, Rey VS, Carrodeguas MV, Castro RG. Profilaxis antibiótica perioperatoria. Rev Int de Cien Pod. 2013;7:109–14.

Lim W, Wu C. Balancing the risks and benefits of thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing podiatric surgery. Chest. 2009;135:888–90.

Felcher AH, Mularski RA, Mosen DM, Kimes TM, De Loughery TG, Laxson SE. Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolic disease in podiatric surgery. Chest. 2009;135:917–22.

Becerro De Bengoa R, Losa ME, Cervera LA, Fernández DS, Prieto JP. Efficacy of intraoperative surgical irrigation with polihexanide and nitrofurazone in reducing bacterial load after nail removal surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:328–35.

Becerro de Bengoa R, Losa ME, Cervera LA, Fernández DS, Prieto J. Preoperative skin and nail preparation of the foot: Comparison of the efficacy of 4 different methods in reducing bacterial load. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:986–92.

Ostrander RV, Botte MJ, Brage ME. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:980–5.

Beckingsale TB, Greiss ME. Getting off on the wrong foot: Doctor–patient miscommunication: A risk for wrong site surgery. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17:201–2.

Schweitzer KM, Brimmo O, May R, Parekh SG. Incidence of wrong-site surgery among foot and ankle surgeons. Foot Ankle Spec. 2011;4:10–3.

Coheña M, García J, Córdoba A, Juárez J, Montaño P. Proposal of a Surgical Security Checklist in Podiatric Surgery. Clin Res Foot Ankle. 2014;2.

Nilsson L, Lindberget O, Gupta A, Vegfors M. Implementing a pre‐operative checklist to increase patient safety: a 1‐year follow‐up of personnel attitudes. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:176–82.

Martínez O, Gutiérrez S, Liévano SA. Propuesta para implantar una Lista de Verificación de Seguridad en procedimientos invasivos y quirófano. Rev CONAMED. 2011;16:53–8.

Hawkins RB, Levy SM, Zhao JY, Doody KA, Lally KP, Kao LS, et al. Assesment of the implementation of a Surgical preoperative checklist. J Surg Res. 2012;172:207.

Autar R. The management of deep vein thrombosis: the Autar DVT risk assessment scale re-visited. J Orth Nurs. 2003;7:114–24.

Truran P, Critchley RJ, Gilliam A. Does using the WHO surgical checklist improve compliance to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis guidelines? Surgeon. 2011;9:309–11.

Sewell M, Adebibe M, Jayakumar P, Jowett C, Kong K, Vemulapalli K, et al. Use of the WHO surgical safety checklist in trauma and orthopaedic patients. Int Orthop. 2011;35:897–901.

Vats A, Vincent CA, Nagpal KR, Davies W, Darzi A, Moorthy K. Practical challenges of introducing WHO surgical checklist: UK pilot experience. BMJ. 2010;340.

Rydenfält C, Johansson G, Odenrick P, Åkerman K, Larsson PA. Compliance with the WHO surgical safety checklist: deviations and possible improvements. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:182–7.

Winters BD, Gurses AP, Lehmann H, Sexton JB, Rampersad CJ, Pronovost PJ. Clinical review: checklists-translating evidence into practice. Crit Care. 2009;13:210.

Lyons VE, Popejoy LL. Meta-Analysis of Surgical Safety Checklist Effects on Teamwork, Communication, Morbidity, Mortality, and Safety. West J Nurs Res. 2013;36:245–61.

Wachter RM, Shojania KG, Duncan BW. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2001.

De Vries EN, Eikens MP, Hamersma AM, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. Prevention of Surgical Malpractice Claims by Use of a Surgical Safety Checklist. Ann Surg. 2011;253:624–8.

Cavallini GM, Campi L, De Maria M, Forlini M. Clinical risk management in eyeout patient surgery: a new surgical safety checklist for cataract surgery and intravitreal anti-VEGF injection. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:889–94.

De Vries EN, Prins HA, Crolla RMPH, Den Outer AJ, Van Andel G, Van Helden SH, et al. Effect of a Comprehensive Surgical Safety System on Patient Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1928–37.

Tillman M, Wehbe-Janek H, Hodges B, Smythe WR, Papaconstantinou HT. Surgical care improvement project and surgical site infections: can integration in the surgical safety checklist improve quality performance and clinical outcomes? J Surg Res. 2013;184:150–6.

Butterworth P, Gilheany MFA, Tinley P. Postoperative infection rates in foot and ankle surgery: a clinical audit of Australian podiatric surgeons. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34:180–5.

Zgonis T, Jolly GP, Garbalosa JC. The efficacy of prophylactic intravenous antibiotics in elective foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;43:97–103.

Bliss LA, Ross-Richardson CB, Sanzari LJ, Shapiro DS, Lukianoff AE, Bernstein BA, et al. Thirty-Day Outcomes Support Implementation of a Surgical Safety Checklist. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:766–76.

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AS, Dellinger EP, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–9.

Panesar SS, Noble DJ, Mirza SB, Patel B, Mann B, Emerton M, et al. Can the surgical checklist reduce the risk of wrong site surgery in orthopaedics?-can the checklist help? Supporting evidence from analysis of a national patient incident reporting system. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011;6:18.

Soria-Aledo V, Andre Da Silva Z, Saturno PJ, Grau-Polan M, Carrillo-Alcaraz A. Dificultades en la implantación del checklist en los quirófanos de cirugía. Cir Esp. 2012;90:180–5.

Van Klei W, Hoff R, Van Aarnhem E, Simmermacher R, Regli L, Kappen T, et al. Effects of the introduction of the WHO “Surgical Safety Checklist” on in-hospital mortality: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2012;255:44–9.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the professionals working in the Podiatric clinical area of the University of Seville for their dedication and full readiness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JGP, MCJ, and PMJ developed the study design. JGP and MCJ were responsible for the data collection. PMJ and ACF conducted the data analysis. JGP wrote the manuscript, with contributions from MCJ and ACF. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Manuel Coheña-Jiménez Pedro Montaño-Jiménez and Antonio Córdoba-Fernández contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

García-París, J., Coheña-Jiménez, M., Montaño-Jiménez, P. et al. Implementation of the WHO “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” checklist in a podiatric surgery unit in Spain: a single-center retrospective observational study. Patient Saf Surg 9, 29 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-015-0075-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-015-0075-4